Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 395

December 27, 2014

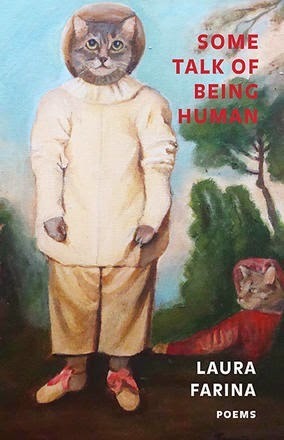

Laura Farina, Some Talk of Being Human

A DEFINITION FOR SNOW

When we went carollingI slipped a compass inside my mittens

and as our voices rosein puffs abovethe white lawnsof our parents’ neighbourhood

you broke into the descant – high notes in the cold air

and secretlyin the palm of my handI pointed the way north.

One might be forgiven for not immediately being aware of the work of former Ottawa poet Laura Farina, given that her first poetry collection, the Archibald Lampman Award-winning This Woman Alphabetical (Pedlar Press, 2005) [see my review of such here] is now nearly a decade old. Now a resident of Vancouver, her second collection is

Some Talk of Being Human

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2014). Much like her first collection,

Some Talk of Being Human

is constructed as a collection of short, observational lyrics, sometimes funny, sometimes a bit abstract and surreal, while others are more direct, all falling under a book title that is perhaps one of the most fitting I’ve seen in some time. Farina’s poems are wistful and contemplative, composed with a quiet humour, a kind of dreamy melancholy that whispers through and between each of her lines, as well as a silence: heavy, pervasive and dark.

One might be forgiven for not immediately being aware of the work of former Ottawa poet Laura Farina, given that her first poetry collection, the Archibald Lampman Award-winning This Woman Alphabetical (Pedlar Press, 2005) [see my review of such here] is now nearly a decade old. Now a resident of Vancouver, her second collection is

Some Talk of Being Human

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2014). Much like her first collection,

Some Talk of Being Human

is constructed as a collection of short, observational lyrics, sometimes funny, sometimes a bit abstract and surreal, while others are more direct, all falling under a book title that is perhaps one of the most fitting I’ve seen in some time. Farina’s poems are wistful and contemplative, composed with a quiet humour, a kind of dreamy melancholy that whispers through and between each of her lines, as well as a silence: heavy, pervasive and dark.GOODBYE

I left the all-night shawarma place.I left the snowbanks and the mittens in them.I left the smell of subways in the rain.I left a library book in a washroom at YVR.I left a gummy bear in the pocket of my jeans.I left my sister waiting at the yoga studio.I left chocolate milk on the aging counter.I left Peterborough, Ontario.I left the Quaker Oats factory,a dark thing in the sunset.

There is a charming matter-of-factness to many of these poems, including an intriguing range of geographies, such as in the poems “A Birthday, a Door, Toronto,” “What the Highway Said to Me,” “I Have Always Been Good at College” and “I Went to Florida,” that begins: “It was hot. / Much of the food was deep-fried // I got sunburned / while taking an architectural walking tour / of South Beach.” And yet, these are not simply observational poems, in or of the moment, but poems that utilize those moments as opportunities to move beyond their borders, shifting into subtle explorations of far larger, abstract, and even mundane considerations. In Farina’s poems, there is the occasional play between meaning and sound, as memories, histories and even the future are explained, questioned and challenged, as are the more banal day to day moments. As she writes in the poem “A Century of Creepy Stories”: “Who tracked dead grass into the empty church? / Why does broken glass always look hungry?”

SOLSTICE POEM

Three bonfiresand the shadows around themare people when they go home.

A bottle breaks,and from somewhere a guitar.

But underneatha silencepressing in like mountainsall around.

It is already darkon the longest day of the year.

Published on December 27, 2014 05:31

December 26, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kerry-Lee Powell

Kerry-Lee Powell

was born in Montreal and has lived in Antigua, Australia and the United Kingdom, where she received a BA in Medieval and Renaissance Literature and an MA in Writing and Literature from Cardiff University. Her poetry has appeared in The Spectator, Ambit and MAGMA. Her fiction has been published in The Boston Review, The Malahat Review and the Virago Press Writing Women series. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize. In 2013 she won The Boston Review fiction contest, The Malahat Review’s Far Horizons award for short fiction and the Alfred G. Bailey manuscript prize. A chapbook entitled

The Wreckage

was published in the United Kingdom by Grey Suit Editions in 2013, and a novel and book of short fiction are forthcoming from HarperCollins.

Inheritance

is her first book.

Kerry-Lee Powell

was born in Montreal and has lived in Antigua, Australia and the United Kingdom, where she received a BA in Medieval and Renaissance Literature and an MA in Writing and Literature from Cardiff University. Her poetry has appeared in The Spectator, Ambit and MAGMA. Her fiction has been published in The Boston Review, The Malahat Review and the Virago Press Writing Women series. She has been nominated for a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize. In 2013 she won The Boston Review fiction contest, The Malahat Review’s Far Horizons award for short fiction and the Alfred G. Bailey manuscript prize. A chapbook entitled

The Wreckage

was published in the United Kingdom by Grey Suit Editions in 2013, and a novel and book of short fiction are forthcoming from HarperCollins.

Inheritance

is her first book.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My book has only recently launched, so it’s hard to say. Over the last few weeks, I’ve felt alternately elated, vulnerable, empowered, anxious, relieved, and really tired. Some of the poems in this collection were written a few years ago, and some more recently. Later poems experiment with longer lines, expand thematically on the austerity and terseness of earlier work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I write both fiction and poetry, and came to poetry after starting off as a fiction writer. Sometimes I’ll have an idea for a poem that turns out to be better suited for a short story or vice versa. I have a book of short fiction coming out next year, and many of the stories were written during approximately the same time period as the poems in this collection.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I recently had this discussion with a couple of writers. I will pretty much always have an ending in mind when I embark on a poem or short story, whereas the writers I spoke with were both compelled to write precisely because they didn’t know where the work would end. Perhaps it’s because I tend to mull and brood a great deal beforehand, and don’t have a sense of an idea or concept as ‘art’ unless I can perceive its shape.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My collection of poetry, Inheritance, is centred around my father’s experiences with post-traumatic stress disorder and his eventual suicide. But this is mainly because it was a powerful subject that I kept returning to without necessarily intending to. I have a great deal of admiration for people who can govern their imaginations well enough to write on any particular subject from the outset. I can’t or at least haven’t yet. I wasn’t aware of any particular theme when writing the stories in my short fiction collection. However, as the stories amassed, I began to see pervasive themes and images. This recognition inspired me to expand upon those themes and write several of the later stories, and it also allowed me to do some substantive editing on earlier pieces.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Some work really lends itself to being read aloud, and I’ve met so many wonderful writers, readers and organizers in the last few weeks. It’s heartening for those of us who live fairly solitary lives to be out amongst actual human beings instead of at a desk with the voices in our heads.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I have been specifically concerned with issues related to post-traumatic stress disorder, trauma and violence. The poems in Inheritance explore the links between PTSD and the ways in which poetry resurrects human experience, particularly through the use of formal devices. Many of the formal poems in this collection are concerned with themes of obedience, rebellion and power. They weren’t written with an agenda in mind, but I feel they explore some uncomfortable issues. Whose voice speaks through me? What does it mean to occupy an archaic form? The questions make me uneasy, but are nonetheless central to my experience as my father’s daughter and as a female artist in a patriarchal culture. And it was very important for me to not shy away from the emotional intensity of the subject matter, to allow the sense of mourning and love and trauma. It strikes me that this is what a lyric poem is in the end, a love song to the culture. And I think that all our stories and myths bear the scars of trauma. In a broader sense, I’m interested in humanism. I’m skeptical about art and its purposes and aims. It strikes me that we too often celebrate self-expression and creativity over what might help to ease suffering on a larger scale. I don’t mean that art should moralize. It’s one of the most rewarding forms of enchantment. But if I was compelled to define its relevance, I would say it’s the best means by which we can both create the world and understand the world as created –by our own perceptions, values and ambivalences.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have a lot of witty, imaginative friends who contribute enormously to their communities and who never read books, let alone read poetry or literary fiction. At the same time I’m persuaded of literature’s absolute value to humanity. We are social beings, communicators. A writer’s influence will always depend on the culture in which their work is read, which is why some writers are popular during their lifetimes while others fall in and out of favor as the centuries pass. Relevance is an issue. As a writer, you have to have something to say.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s sometimes frustrating and painful to work with editors, but you learn what’s worth fighting for. I’ve been lucky enough to work with several of the very best.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

That writing is a physical activity and not a mental one. Anthony Howell, a poet and fiction writer who was once in the Royal Ballet, told me this a few years ago after I’d watched him scribble off and on all day in a notebook he is almost never without. For him, writing in his notebook is akin to a dancer practicing at the barre. It’s a useful way of thinking because it reminds you that with writing, you must exert yourself in order to determine what you’re capable of. And to see if those inner musings can be transmuted. Lead into gold. More often than not for me, it’s the other way around.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short story to novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

Writing is hard! I blame poetry, because it taught me to agonize over every sentence.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I am writing a novel and finding it difficult as a novel involves skills and disciplines that are somewhat alien to me. But it’s good to be challenged, to work at the limit of one’s abilities. On a more mundane level, my day begins with coffee and a notebook. I make lists, try to bust through the anxiety and sense of being overwhelmed by the task ahead.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I’m inspired by paintings and by music, and only rarely these days by movies or other books. However, I am deeply influenced by books I read in the past, canonical figures like Plath and Dostoevski and Nabokov, Lowell and Henry James, as well as lesser-known writers like Yevgeny Zamyatin. In the end, I feel that influences are more like tools or clues in a mystery. What you’re really doing as a writer is learning to find and express your own vision of the world. And this is often a troublesome and troubling journey.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I’ve lived in a few different homes, but as I live in New Brunswick and it’s fall at the moment I’ll say wood-smoke and wet leaves.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I spend quite a lot of time in the woods. They are difficult to avoid out here. In my fiction, I like to contrast the life of the mind, of civilization, with the wildness beyond it. I’m attracted to suburban locales or small towns as settings for that reason, as they show humans situated on the ragged borders of what’s knowable and what’s frighteningly not. I never intended this, but visual art and music have become vital to my practice. My poetry is often formal and very sound-oriented. My short fiction collection is called ‘Willem de Kooning’s Paintbrush’ and the titular story was inspired by the violence of his technique in several paintings. I’m idea-driven but I have an artisanal approach and tend to focus on texture and style.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My partner, who’s taking a couple of years off from university at the moment, studies philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His observations about consciousness, neuroscience and the mind continue to amaze and inspire. It’s an area where there are a lot of misguided pop notions and I appreciate his lucidity. Other writers I’ve recently been inspired by include poet (and now friend) Stevie Howell, whose new book approaches similar themes to mine but in a totally different, and brilliant, manner. I’ve been reading with her off and on for the last few weeks and my appreciation of her work continues to deepen.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Finish my novel! Then travel, maybe to Eastern Europe. Somewhere I’ve never been.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

At one point I thought I’d do a PhD in medieval literature. At another point I thought screw it, I’ll be a landscape gardener or go back to bartending. I enjoy physical work and I made more money as a cocktail waitress then in any job I’ve had before or since. But I do value and require plenty of time alone these days.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

As a kid I always wanted to be a writer and made up little booklets that I gave out to friends. I wrote the usual dark stuff as a teen and had some early success with publishing work in literary magazines and interest from publishers in my twenties. But I ran away from it all. I hated my work back then, felt like I was a phony. Then I tried not writing for a while, but that didn’t work out very well either! It’s an ongoing act of bravado for me to put it out there, to not fall back into silence.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book was Lynn Emanuel’s fabulous book of poetry called The Dig. Tony Hoagland told me to read it as a cure for my tendency towards terseness and I’m thankful he did. Can I pick two movies? One great film was Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, which I hated the first time around and then watched again a few weeks ago and was blown away. A masterpiece. The other was Pan’s Labyrinth which accomplishes everything I’ve ever wanted to do as a writer in about an hour and a half.

20 - What are you currently working on?

The novel! I’m also writing a little non-fiction these days, taking notes, feeling my way around the form.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on December 26, 2014 05:31

December 25, 2014

merry christmas season holiday etc (apparently we have cards now,

Published on December 25, 2014 05:31

December 24, 2014

some (early) christmas : montebello,

With Christine's father and his wife Teri, Christine's brother Michael and his wife Alexis (and baby Duncan), we did our second annual Montebello over the weekend, for McNair Christmassy-type celebrations [see last year's post on such]. At least, this year, I didn't have to worry about having to recharge the battery on our old car (since passed along to a cousin, given a two-door is tricky to navigate baby into/out of carseat). Given that Rose is a year old now, she was much more user-friendly during this trip, waving excitedly at anyone and everyone who passed by, and we gave her more than a couple of opportunities to walk and run (supervised) through the huge Montebello space.

With Christine's father and his wife Teri, Christine's brother Michael and his wife Alexis (and baby Duncan), we did our second annual Montebello over the weekend, for McNair Christmassy-type celebrations [see last year's post on such]. At least, this year, I didn't have to worry about having to recharge the battery on our old car (since passed along to a cousin, given a two-door is tricky to navigate baby into/out of carseat). Given that Rose is a year old now, she was much more user-friendly during this trip, waving excitedly at anyone and everyone who passed by, and we gave her more than a couple of opportunities to walk and run (supervised) through the huge Montebello space.

We drove out early on Saturday for the sake of outdoor winter-ings, but the warmer temperatures made the trails difficult, and we didn't think Rose would tolerate the rental sleds (we should have brought the sled she received for her birthday), so our walk outdoors was rather contained. It was even too warm for the sleigh rides! But we walked for a bit around the grounds, Rose enjoyed her time on the swings (she loves swings), and she saw a helicopter lift off from the other side of the massive hotel complex.

We drove out early on Saturday for the sake of outdoor winter-ings, but the warmer temperatures made the trails difficult, and we didn't think Rose would tolerate the rental sleds (we should have brought the sled she received for her birthday), so our walk outdoors was rather contained. It was even too warm for the sleigh rides! But we walked for a bit around the grounds, Rose enjoyed her time on the swings (she loves swings), and she saw a helicopter lift off from the other side of the massive hotel complex. Christine attempted the swimming pool with Rose, but baby would have none of it, crying the whole time until I pulled her out to wrap up in towels (I didn't think anyone wanted to see screamy swimming photos, so haven't included them here). Once she was out of the pool, she was quite content to sit on the sidelines with me, pointing at all the other people flailing about in the eighty-plus degree water. Rose played with Teri, hugged her grandfather's leg, rifled through her aunt Alexis' presents, played with her uncle Michael, and very much enjoyed seeing her new-ish cousin Duncan (the second grandchild, after Rose, on the McNair side). At one point, she went to kiss his face, as Duncan attempted to latch onto her nose.

Christine attempted the swimming pool with Rose, but baby would have none of it, crying the whole time until I pulled her out to wrap up in towels (I didn't think anyone wanted to see screamy swimming photos, so haven't included them here). Once she was out of the pool, she was quite content to sit on the sidelines with me, pointing at all the other people flailing about in the eighty-plus degree water. Rose played with Teri, hugged her grandfather's leg, rifled through her aunt Alexis' presents, played with her uncle Michael, and very much enjoyed seeing her new-ish cousin Duncan (the second grandchild, after Rose, on the McNair side). At one point, she went to kiss his face, as Duncan attempted to latch onto her nose. We had a lovely time, and Rose was extremely well-behaved during the entire trip, even when fidgety during parts of the meals (I simply walked a few minutes with her down some of the myriad hallways). She waved at everyone, and charmed just about everyone in the hotel (including the occasional person that seemed grumpy--how could anyone be grumpy while staying at Montebello?). Before dinner on the Saturday, Christine even managed to get Rose out for a brief nap on her back, in one of the wraps (there was so much activity that she wanted to pay attention to, all the time, so I'm impressed she managed it).

We had a lovely time, and Rose was extremely well-behaved during the entire trip, even when fidgety during parts of the meals (I simply walked a few minutes with her down some of the myriad hallways). She waved at everyone, and charmed just about everyone in the hotel (including the occasional person that seemed grumpy--how could anyone be grumpy while staying at Montebello?). Before dinner on the Saturday, Christine even managed to get Rose out for a brief nap on her back, in one of the wraps (there was so much activity that she wanted to pay attention to, all the time, so I'm impressed she managed it).And: by the time you are reading this, I'm in the midst of putting turkey in the oven, to host various of our small McLennan clan at our house, hosting father, sister etc and daughter Kate for our first non-farm Christmas. I've been baking!

Published on December 24, 2014 05:31

December 23, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mary Kasimor

Mary Kasimor has most recently been published in

Yew Journal

,

Big Bridge

,

MadHat

,

Horse Less Review

,

Altered Scale

,

Word For/Word

, Posit,

Otoliths

,

EOAGH

, and

The Missing Slate

. She has three previous books and/or chapbook publications:

Silk String Arias

(BlazeVox Books),

& Cruel Red

(Otoliths), and

The Windows Hallucinate

(LRL Textile Series). She has a new collection of poetry published in 2014, entitled

The Landfill Dancers

(BlazeVox Books). She also writes book reviews that have been published in

Jacket

, Big Bridge,

Galatea Resurrects

, and Gently Read Literature. She considers her work experimental—both her poetry and ink/water colors.

Mary Kasimor has most recently been published in

Yew Journal

,

Big Bridge

,

MadHat

,

Horse Less Review

,

Altered Scale

,

Word For/Word

, Posit,

Otoliths

,

EOAGH

, and

The Missing Slate

. She has three previous books and/or chapbook publications:

Silk String Arias

(BlazeVox Books),

& Cruel Red

(Otoliths), and

The Windows Hallucinate

(LRL Textile Series). She has a new collection of poetry published in 2014, entitled

The Landfill Dancers

(BlazeVox Books). She also writes book reviews that have been published in

Jacket

, Big Bridge,

Galatea Resurrects

, and Gently Read Literature. She considers her work experimental—both her poetry and ink/water colors.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book or chapbook did not really change my life. It was exciting in a way, but each time I begin a poem I feel as though I am writing for the first time. What I am saying is that it didn’t increase my sense that I had “made it” in anyway.

My work has become more experimental and organic than my earlier poems, even though I was moving in that direction even with my first book.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wanted to be able to write quickly, and that is easier to do with poetry than fiction or non-fiction. I also feel closer to the spirit of poetry, and it is more magical to me. It is also more visual than fiction and non-fiction, and my poetry is visual.

I did not read much fiction for a long time because I wasn’t very interested in fiction. I now enjoy and read novels and non-fiction. I read non-fiction that is philosophical or scientific.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I rarely procrastinate when I begin a project. One reason for that is because my writing is usually very spontaneous. It is difficult for me to decide to write about a specific idea or theme, and as a result, my writing is about what is on my mind at the moment. In the chapbook entitled Duplex, I wrote about my children and how I related to them. That book is not as interesting to me as my other books and chapbook because it was somewhat planned and focused. I think that my writing is best when I am not focused on a theme or idea or even style.

My drafts change during the course of my writing. I first write in a notebook and revise in a notebook. Then I transfer it to a computer and revise over and over again. The revision process is important in my writing.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem begins with something that I am usually thinking about. Sometimes a line is very random and that is the beginning of a poem. It is rare for me to work on a “book” from the beginning. I want to be able to explore ideas, words, images, sounds, and I don’t want to be limited by structure or theme.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t do many readings. I am always concerned that people will either dislike or not understand my poetry. I think that my poetry is better read than listened to by an audience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In my poetry I am trying to get into the essence of where we as humans began and how we fit with other sentient or non-sentient matter. Several years ago I read Lynn Margulis’ essays on evolution and I found them fascinating. I continue to try to understand her theories through my poetic form.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer should be telling people what they don’t want to hear about themselves—the cruel and ugly and stupid, and also the surprisingly wonderful things about being alive and/or human.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Since the editors whom I’ve worked with have given me complete freedom, I do not find it difficult working with an outside editor. The editors have been from small presses, and maybe that is why I feel that I have a great deal of freedom.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was working on my MA in English, I was planning to write a thesis on Deconstruction as it applied to Barbara Guest’s poetry. Several good friends advised me to write a creative thesis instead, and I decided to follow their advice—and it was good advice.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

In my opinion, writing both poetry and critical prose requires creativity and deep thinking. I do write reviews of poetry, and I have found that I become part of a creative process while I am writing it and throughout all my revisions, and there is something deeply satisfying about writing reviews. However, writing poetry is more creative and more difficult.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try to write every day, and writing in the morning is the best time. My writing process is not terribly structured. I will leave the beginning of a draft, returning to it many times with new ideas.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read other poets whose poetry I greatly admire. Several examples would be Anne Carson (of course) and Lyn Hejinian.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilacs remind me of Minnesota, which is where I grew up and consider home, even though I live in Washington now. It reminds me of home because lilacs bloom after a hard and cold winter.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Visual art and jazz influence my poetry. I love abstract art and the great jazz musicians (Coltrane, Davis, Parker…)

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I enjoy reading books about science, as long as it is written for the non-scientist. I am catching up on many of the great novels—I just finished reading The Idiot.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to travel more. I also want to continue writing and writing.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I find science fascinating. If I had a scientific mind, I would have loved to go into research.

I taught writing and literature courses, and I usually looked forward to teaching.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I loved music, but I realized my limitations. Writing poetry worked for me. I never know what I am going to do next, and that is part of the beauty of writing.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I have read many great books, and the last great book that I read was The Idiot . The characters and situations that Dostoyevsky created were intriguing. His interpretation of human nature was ultimately tragic.

The last great film that I’ve seen was The Artist . I can only describe it as being charming and delightful. I have actually seen other great movies since The Artist, but this is one of my favorites.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on a new chapbook, and I am letting the poems lead me. I don’t know what I will do with the chapbook once I am finished with it. Maybe someone will publish it or maybe it will just remain in my computer files.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on December 23, 2014 05:31

December 22, 2014

Dorothea Lasky, Rome

THE AMETHYST

All my lifeIt was a lieTo try to go towards blissBut death is the ultimate blissfulnessTo be a candy or a corpseThe world holds you on its tongueAnd no one can save youNot even your own children or your friendsSo have a seat with the home of the deadThey will eat your colorsUntil you are blankThe best thing to happen to youThe greatest happinessTo be an animal who is smokeAnd beyond the mouthThat tears your bones from one anotherTo be a mound of meatAt the table of the living

Brooklyn poet Dorothea Lasky’s fourth poetry collection is Rome (New York NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2014), following

Thunderbird

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Black Life

(Wave Books, 2010) [see my review of such here] and

AWE

(Wave, 2007) [see my review of such here]. In the past, Lasky’s work has been compared to the work of both Frank O’Hara and Allen Ginsberg, and the influence of O’Hara’s “I did this, I did that” strain of lyric narrative is unmistakable. Both O’Hara and Ginsberg were also performative sentence-poets, writing out their immediate world as they understood it, and the performance poem-essays that make up Lasky’s Rome is clearly immersed in much of the same approach. Much like Lisa Robertson (but in a more narrative vein) and Lisa Jarnot, Lasky is very much a poet of sentences and stark phrases, allowing them to speak and shout and whisper and silence when appropriate, and even provide the occasional gut-punch. The final stanza of the piece “Poem to Florence,” for example, reads:

Brooklyn poet Dorothea Lasky’s fourth poetry collection is Rome (New York NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2014), following

Thunderbird

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Black Life

(Wave Books, 2010) [see my review of such here] and

AWE

(Wave, 2007) [see my review of such here]. In the past, Lasky’s work has been compared to the work of both Frank O’Hara and Allen Ginsberg, and the influence of O’Hara’s “I did this, I did that” strain of lyric narrative is unmistakable. Both O’Hara and Ginsberg were also performative sentence-poets, writing out their immediate world as they understood it, and the performance poem-essays that make up Lasky’s Rome is clearly immersed in much of the same approach. Much like Lisa Robertson (but in a more narrative vein) and Lisa Jarnot, Lasky is very much a poet of sentences and stark phrases, allowing them to speak and shout and whisper and silence when appropriate, and even provide the occasional gut-punch. The final stanza of the piece “Poem to Florence,” for example, reads:There were things I wished I’d saidAnd doneBut it is too late nowSo I goHeavy with my offeringThis book, this book

The ten-poem sequence that lends the book its title plays off considerations of the city of Rome, the fictions of real and imagined lives, and a grandness of history against certain disappointments of the contemporary: “Rome is about the Colosseum / Said the cashier in the local market / Where I went with my mother / In the town I grew up in / No longer a young man / But tunneling towards a ferocity / Not anyone could have predicted [.]” Throughout the title poem, as well as sprinkled through the book as a whole, Lasky forces confrontations between classical knowledge and the contemporary, pushing a darker series of tones through romantic ideas and ideals, as well as an exploration of some corners that aren’t often articulated (or so well) in contemporary poetry. As she writes in the poem “Porn”: “I watch porn / Cause I’ll never be in love / Except with you dear reader / Who thinks I surrender [.]” Part of what makes Rome so striking is in the way she writes the intimately personal so deeply dark, as though each line somehow a nail-scratch seeking blood beneath the skin. Listen to the opening stanzas of the poem “Moving,” as she writes:

Yes, I am moving but I am notI will never see my body deadIn the way I have seen yours

The soul never sleepsI told youAfter you were gone

What was your nameI kept moving onUntil I did not need you anymore

Published on December 22, 2014 05:31

December 21, 2014

the return of The Peter F. Yacht Club regatta/reading/christmas party!

lovingly hosted by rob mclennan;

lovingly hosted by rob mclennan;The Peter F. Yacht Club annual regatta/christmas party & issue launch for The Peter F Yacht Club #21: edited/produced by rob mclennan

at The Carleton Tavern (upstairs)

233 Armstrong Avenue (at Parkdale Market), Ottawa

Monday, December 29, 2014

doors 7pm, reading 7:30pm

with readings from yacht club regulars and irregulars alike;

Published on December 21, 2014 05:31

December 20, 2014

fwd: THE WRITERS' UNION OF CANADA ANNOUNCES 22nd ANNUAL SHORT PROSE COMPETITION FOR DEVELOPING WRITERS

The Writers' Union of Canada is pleased to launch its 22nd Annual Short Prose Competition for Developing Writers, which invites writers to submit a piece of fiction or non-fiction of up to 2,500 words in the English language that has not previously been published in any format. A $2,500 prize will be awarded to a Canadian writer not published in a book format. The entries of the winner and finalists will be submitted to three Canadian magazines for consideration. The deadline for entries is March 1, 2015.

The Writers' Union of Canada is pleased to launch its 22nd Annual Short Prose Competition for Developing Writers, which invites writers to submit a piece of fiction or non-fiction of up to 2,500 words in the English language that has not previously been published in any format. A $2,500 prize will be awarded to a Canadian writer not published in a book format. The entries of the winner and finalists will be submitted to three Canadian magazines for consideration. The deadline for entries is March 1, 2015.The Union initiated the Short Prose Competition in 1993 in honour of its 20th anniversary. The Competition aims to discover, encourage, and promote new writers of short prose. “The Short Prose Competition attracts a wide pool of talented writers,” notes the Union’s Executive Director, John Degen. “The quality of the writing continues to impress with each passing year.”

The Union is proud to announce an esteemed group of jurors for the Competition. Vancouver-based environmental journalist and author Arno Kopecky’s second book, The Oil Man and the Sea, won the 2014 Edna Staebler Award for Creative Nonfiction and was shortlisted for the 2014 Governor General's Award. His writing has appeared in such publications as The Walrus, Foreign Policy, The Globe and Mail, and Reader’s Digest. Donna Morrissey is the award-winning author of Kit's Law, Downhill Chance, What They Wanted, Sylvanus Now (shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers' Prize), and the children’s book Cross Katie Cross. Originally from Newfoundland, she now lives in Halifax. Retired Professor of English, University of Winnipeg, Uma Parameswaran is known for her contributions to the emerging field of South Asian Canadian Literature, writing novels, short stories, and poetry. Her works include A Cycle of the Moon, Sisters at the Well, The Sweet Smell of Mother’s Milk-wet Bodice, and the Canadian Authors' Association Jubilee Award-winning What Was Always Hers.

The competition is open to Canadian residents who have not had a book published and who do not have a contract with a book publisher. Submissions are accepted online (along with a $29 entry fee per submission) at www.writersunion.submittable.com by 11:59 pm Pacific Time on March 1, 2015. The winner will be announced in May 2015. For complete rules and regulations, please go to www.writersunion.ca/short-prose-competition .

The Writers' Union of Canada is the national organization representing professional book authors. Founded in 1973, the Union is dedicated to fostering writing in Canada and promoting the rights, freedoms, and economic well-being of all writers. For more information, please visit www.writersunion.ca

Published on December 20, 2014 05:31

December 19, 2014

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rodney Koeneke

Rodney Koeneke’s latest poetry collection,

Etruria

, is just out from Wave Books. He’s also the author of

Musee Mechanique

and

Rouge State

, as well as four chapbooks. He studied history at U.C. Berkeley and Stanford, and currently teaches it in Portland, Ore.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? rob, it’s been so long since my first book—over 10 years—that I can’t quite remember. I suppose it was affirming, like it is for anyone. Then you go back to the silence to pull out more poems, and the book’s like a snapshot on your desktop of that vacation you took that one year.2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? Stung by a bee on the lip as a youth. 3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? I tried to answer this one for you rob, but it varies so much from poem to poem that I couldn’t make an accurate generalization.

Rodney Koeneke’s latest poetry collection,

Etruria

, is just out from Wave Books. He’s also the author of

Musee Mechanique

and

Rouge State

, as well as four chapbooks. He studied history at U.C. Berkeley and Stanford, and currently teaches it in Portland, Ore.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? rob, it’s been so long since my first book—over 10 years—that I can’t quite remember. I suppose it was affirming, like it is for anyone. Then you go back to the silence to pull out more poems, and the book’s like a snapshot on your desktop of that vacation you took that one year.2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? Stung by a bee on the lip as a youth. 3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? I tried to answer this one for you rob, but it varies so much from poem to poem that I couldn’t make an accurate generalization. 4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? My three books so far have been collections of poems, few longer than two pages. “The book” starts to happen at around 50 poems I can live with. 5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? Readings help find the 50 I can live with. Don’t all writers enjoy readings? They sure enjoy readers.6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? What is a poem? What can poetry do? 7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be? I like thinking of Skelton at Diss, shaking fists at Wolsey. “Ware the Hawk.”8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? Essentially difficult? 9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? No one listens to poetry. Wait. That’s got a nice ring. rob, feel free to use that somewhere.10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal? Prose is a snow machine; poetry’s snow. 11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? A typical day begins with routine, which I try to keep poetry free from. 12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? Other poets.13 - What fragrance reminds you of home? Other poets.14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? I went to Google for this one to meet David W. McFadden, and it tells me “his poetry critiques the commercialism and shallowness of modern society.” 15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? O rob, that’s a dangerous question! You’ll get one of those panicky Academy Award-type speeches that keeps cramming in more and more names, but somehow omits mom and dad.16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? Question 17.17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? Plastics.18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? Seems I’m made to do lots of something else, as opposed to writing.19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? Against the Day. Solaris?20 - What are you currently working on? I just finished a chapbook for Oakland’s Hooke Press that Brent Cunningham’s editing. It’s called Seven for Boetticher and Other Poems and it’ll be out later this year. I’m also at work with the great Team Wave to help Etruria find its way in the world.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on December 19, 2014 05:31

December 18, 2014

Michelle Detorie, After-Cave

In motion is how we live, sleeping inside skin. I want wheels turning only in, around. My clothes, they get thin as I get worn. We were looking out for tracing clouds, fin slid under wing. We were without beds. I nurtured sounds. We came to land on land like rest. We fluttered full to nest only sticks built into temporary chambers. (“Fur Birds”)

Following the publication of a series of chapbooks through Insert Press, eohippus labsand dusie, Santa Barbara, California poet Michelle Detorie’s lively first trade poetry collection is After-Cave (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2014). Composed in three sections, each of which are constructed via a collage of untitled poem fragments, prose-pieces and short lyrics, she opens the first section, “Fur Birds,” with “I am 15. Female. Human (I think).” The poems then move into an exploration of what the book describes as “feral life,” disappearing into the wilderness and abandoning numerous comforts of human culture, writing:

Digging underground, I disrupted homes that did not belong to mebut wound deep and tethered together. I thought of coupling tunnels and the downward wind of tubed figure-eights. Like swans leaning in, their necks so long: the forged reflection the rubbed-out lake

Remember: her narrator may or may not be human, openly admitting at the offset to a rather considerable uncertainty, allowing the reader to find nearly anything else the narrator describes as possibly suspect, however open and sincere ‘her’ descriptions, admissions and considerations might be. Exactly what might our narrator be describing, one might wonder, or do we simply take her at her word? The way the accumulation of short pieces stitch into each other to create a larger construction is quite impressive, and her section-fragments shift and shimmy between abstract considerations, pure description, articulations of shelter, displays of animalistic tendencies, and talk of social interactions, shifting between a narrator who claims to have left the world long behind (in the ‘mad hermit in the woods’ sense), to someone who has merely stepped away for a moment. Towards the end of the collection, Detorie admits to the possibility of the abstract and even contradictory qualities of what this unnamed narrator presents: “To insist that something—someone or some being—cannot be / imagined is, in fact, its own form of oppression.” As poet and critic Bhanu Kapil suggests in her back-cover blurb, this is very much a collection exploring a space between “feral life and the ecology of shelter.”

Remember: her narrator may or may not be human, openly admitting at the offset to a rather considerable uncertainty, allowing the reader to find nearly anything else the narrator describes as possibly suspect, however open and sincere ‘her’ descriptions, admissions and considerations might be. Exactly what might our narrator be describing, one might wonder, or do we simply take her at her word? The way the accumulation of short pieces stitch into each other to create a larger construction is quite impressive, and her section-fragments shift and shimmy between abstract considerations, pure description, articulations of shelter, displays of animalistic tendencies, and talk of social interactions, shifting between a narrator who claims to have left the world long behind (in the ‘mad hermit in the woods’ sense), to someone who has merely stepped away for a moment. Towards the end of the collection, Detorie admits to the possibility of the abstract and even contradictory qualities of what this unnamed narrator presents: “To insist that something—someone or some being—cannot be / imagined is, in fact, its own form of oppression.” As poet and critic Bhanu Kapil suggests in her back-cover blurb, this is very much a collection exploring a space between “feral life and the ecology of shelter.” We measured the mountains.This small sadness:I can hold in my swale, tasteit only tongue. Saltshowers and the glowinside bones—lit up,electric signs. The desertis the pain of home, the homeaway. This withholding—it makes me pine all the more.Sympathy is a craving. The stonearound us turns to ice.

Published on December 18, 2014 05:31