Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 380

May 28, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Madhur Anand

Madhur Anand’s poetry has appeared in literary magazines across North America and in

The Shape of Content: Creative Writing in Mathematics and Science

(AK Peters/CRC Press, 2008). She co-edited

Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry

(Scrivener Press, 2009).

A New Index For Predicting Catastrophes

(McClelland and Stewart, 2015) is her first full-length poetry collection. Anand completed her PhD in theoretical ecology at Western University and is currently Full Professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph. She lives in Guelph with her husband and three young children.

Madhur Anand’s poetry has appeared in literary magazines across North America and in

The Shape of Content: Creative Writing in Mathematics and Science

(AK Peters/CRC Press, 2008). She co-edited

Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry

(Scrivener Press, 2009).

A New Index For Predicting Catastrophes

(McClelland and Stewart, 2015) is her first full-length poetry collection. Anand completed her PhD in theoretical ecology at Western University and is currently Full Professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph. She lives in Guelph with her husband and three young children.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The only big change I’ve noticed is that lately I am much less obsessed with reading and writing poetry and a little more obsessed with reading and writing prose.

The most recently written poems in the book arose out of a forced, but necessary, confrontation with my own scientific research. I seemed to have avoided doing that for a long time, but I’m glad I finally did it.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As I have elaborated on elsewhere [http://ifoa.org/2015/five-questions-with/five-questions-with-madhur-anand], I got hooked on poetry when I discovered it was a way to inject a perpendicular mode of being and thinking into my life’s dominant, and sometimes predictable, course. Though I enjoyed fiction and non-fiction very much, they seemed either too acute or too obtuse at the time for this particular purpose.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The writing is sometimes quick and sometimes slow. First drafts are almost never in their final shape. Some methods of writing, perhaps because of the extremely concentrated focus or constraint they demand (such as with ‘found’ poems, villanelles, and sestinas), can lead to almost final first drafts.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A thought, a concept, a memory, a theory, striking language -- all usually in reference to beauty, loss or fascination. My first book was a combination of poems written over many years, but there were common themes (biology, complexity, critical transitions). In the process of editing, and after choosing my title, many new poems were inspired. So, in the end, it was a bit of both.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I haven’t done very many public readings, so I don’t know yet. I certainly find it enjoyable and inspiring to attend readings by other poets.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I am concerned, perhaps preoccupied, with the relationship between science and poetry. We don’t have a sufficient theory to explain this relationship. I am also concerned with the role of constraint in poetry. A large number of the poems in the book are written in syllabics. Though obviously intentional and strictly self-enforced, I don’t fully understand how this kind of constraint works, and the need for it, fundamentally. My book also has a couple of villanelles and several found poems. These are other forms of constraint, and some of them have been written about in fascinating ways (see for example the essay entitled “Life Forms: Elizabeth Bishop’s “Sestina” and “DNA Structure” in the book Unified Fields edited by Janine Rogers). But I want my understanding of this to go beyond metaphor.

The questions I am trying to answer in my poems are the same questions that appear on the NASA poster hanging in my little boy’s bedroom: “Life: What is it? Where is it? How do we find it?” NASA is still asking these questions, and I think we all should be too, constantly.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

“Writer” is such a broad category; all writers won’t have the same role. Poets are still (as Shelley once articulated) the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’. This ‘legislation’ is not only restricted to human-human interactions but potentially many other undiscovered laws of the universe.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. I’ve loved every editor I have worked with (and there were many). Dionne Brand, poetry board member at M&S had the job of doing the final edit of my book, and what she asked of me, what we did together was marvelous and well, essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Read this:” [insert any brilliant work of poetry or prose that I have not yet heard of here].

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no daily writing routine. I have a full-time job as a professor of ecology and three young children. I write when I can. I have more of a yearly routine. Every year I try to do at least one intensive thing for my writing such as a retreat or a workshop.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Better writing (that is, I read). Or I go for a walk.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

North Indian spices. Smoke from making chapatis because we don’t have a range hood. Johnson & Johnson baby lotion. Vick’s Vapour Rub.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think that most of the time books come from other books. Many other forms (disciplines) influence my work, but most of all, science.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

At the back of my book you’ll find the names of all the writers who have indirectly or directly mentored or helped my work in some significant way It’s a very long list that includes Don McKay, Paul Vermeersch and Phil Hall. These individuals, and their works have been influential. As for other writings, it’s harder to say. There are so many. But an early influential event was picking up a copy of Robyn Sarah’s book The Touchstone at Paragraphe Bookstore in Montreal when I was just starting to take my writing seriously over 15 years ago. I would visit bookshops in every city I travelled to (mostly to give scientific talks) and pick one or two poetry books from among the selection offered. That was my poetry education. I was also influenced early on by the work of Wislawa Szymborska. I have subscribed continuously to Poetry magazine since 2003. I love that magazine, and it has helped to expose me to a diversity of contemporary writing.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Publish a second book of creative writing.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Given that I have the two professions I adore most, am committed to, and am constantly reinventing, plus a rather full family life, I can’t even imagine any other occupation. When I was 17, I turned down an offer from McMaster University to do an undergraduate degree in their highly coveted “Arts and Science” program. I choose pure science at Western instead. But I always wondered about that path not taken. I am thrilled that I did not end up having to make the choice between art and science in my life.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The love of it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

A Room on the Roof by Ruskin Bond. The last great film was probably something from years ago such as The Five Obstructions by Lars von Trier. I can’t recall any more recent films worth mentioning right now (sorry, great films!).

19 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on numerous things in my scientific profession -- see

(http://www.uoguelph.ca/~manand/Madhur_Anand/Welcome.html).

I’m also helping to raise 3 kids and piecing together various sets of ideas and materials for what could be my next creative writing project (or not).

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on May 28, 2015 05:31

May 27, 2015

Ongoing notes: later May 2015

Like a lot of my stories, that one just followed one momentary thought—What am I doing here, putting odd sentences together and creating some little piece of nonsense, when people are dying on the other side of the world and our government’s going to damnation? It’s something that a lot of artists, I’m sure, feel at one time or another, that they’re wasting time or doing something frivolous. So instead of answering myself and ignoring it, I wrote it out as a little thought. I didn’t know how much value to give to that story, but I showed it to a very serious critic and she liked it, so I decided it passed. Lydia Davis, The Art of Fiction No. 227, The Paris Review

There’s been a ton of activity around here lately, or perhaps there hasn’t; perhaps my time full-time with toddler has shifted my perspective. Who knows? I bake, I wander with wee babe to the park, and the occasional reading even happens. Currently I’m in the midst of a slew of new above/ground press publications for the upcoming semi-annual ottawa small press book fair weekend, on June 12 and 13: might we see you there?

There’s been a ton of activity around here lately, or perhaps there hasn’t; perhaps my time full-time with toddler has shifted my perspective. Who knows? I bake, I wander with wee babe to the park, and the occasional reading even happens. Currently I’m in the midst of a slew of new above/ground press publications for the upcoming semi-annual ottawa small press book fair weekend, on June 12 and 13: might we see you there?Rose turned eighteen months last week. Her big sister Kate gifted her a “Flash” mask, which means, of course, there can only be blurry photos.

Prince George BC: Rob Buddewas good enough to send me a copy of Kara-lee MacDonald’s Eating Matters (Hobo Books, 2015), a chapbook of poems exploring eating disorders and the social pressures/expectations of women. The collage aspect of the collection, very much composed as a single project, is rather interesting. Some pieces might be less effective than others, but the variety and scope of the structure makes the read more than worth it. To see how one might get a copy, check with karaleemacdona@gmail.com

The hardest part is knowingthat she should know better.It isn’t as if she isn’t educated—as if she isn’t well-read. She can tell you

what de Beauvoir says,what Butler says,what Bordo says.

At the end of the way,—theory failsto account for disjunctionbetween bodily urges and rational thought.

When the late hour and quiet househave broken her resolve,she responds predictably.

A trip to the kitchen beforeinducing in the bathroom.Running water to maskthe sounds.

Philadelphia PA: From Brian Teare’s Albion Books comes Jean Valentine’s small chapbook friend (2015), a collection of lyrics that appear to reference her prior poem for Adrienne Rich, a piece that shares a similar title. An award-winning New York City poet, Valentine is the author of numerous books, and winner of a wide array of awards, from the Wallace Stevens Award and the Shelley Memorial Prize. The short poems in friend are carefully composed and packed tight, while still allowing a particular looseness to breathe between her lines.

MY WORDS TO YOU

My words to you are the stitches in a scarfI don’t want to finishmaybe it will come to be a blanketto hold you here

love not gone anywhere

Perhaps extending from that previous piece, these poems explore the attachments between people. She writes of loss and love, and even deeper bonds, such as the final stanza of the poem “AFTER: ISN'T THERE SOMETHING,” that reads:

I want to go back to you,who when you were dying said“There are one or two people you don’t want tolet go of.” Here too, where I don’t let go of you.

Toronto ON: The recently-launched Toronto chapbook publisher, WORDS(ON)PAGES, released a small handful of chapbooks this past spring, including Daniel Scott Tysdal’s THE DISCOVERY OF LOVE (2015), “COMPOSED ON THE OCCASION OF THE PUBLICATION OF THE DISCOVERY OF LOVE, WHICH MARKED THE THIRTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PASSING OF THE GAY MARRIAGE ACT ON JANUARY 18, 1979.”

The discovery? Yes, ma’am, I remember,clear as day. I was searching the Good Bookfor a verse that would really stick it tothe homosexuals. You see, that was howI thought back in ’77. It was late, whichI don’t remember so much as know. I stilldon’t sleep well when travelling, eventhough that night I was in Dade Country, onlyan eight hour drive from my own bed [laughs].Dade’s where they were passing that law,you see, to help the homosexuals. Or stophurting them. [Pauses] I don’t recall.Either way, the lot of us Pastors and Deaconswere madder than mules chewing bees[laughs], ready to bring down all the lightand fire of the Lord on those heathencouncilors in Miami. And then ithappened. [Pauses]. This I rememberas clear as day. I saw that word and I feltGod’s own great hands wrap me up likea blanket round a baby and for the first time I truly felt [pauses] Him, [pauses]I mean us, us, the power He granted uswith this one word that changed the wholeballgame: love. It was right there in John’sFirst Epistle: “We love because He first lovedus.” I couldn’t believe we had missed it!

Lord forgive us, for centuries! [Laughs.]And the scriptures were just stuffed withit. Mark 12:31, “Love your neighbor asyourself.” Romans 13:8: “Let no debtremain outstanding, except the continuingdebt to love one another.” (“1. THE FORMER PASTOR MAYHEW RAY”)

Subtitled “EXCERPTS FROM AN ENDLESS ORAL HISTORY,” Tysdal’s five-part poem exists as both celebration and historical warning, utilizing real events for the sake of a lyric-through-accretion. Tysdal’s published poetry to date, which include a small handful of trade collections and small chapbooks, are each constructed in unexpected ways, utilizing collage, the idea of the archive and folded materials to produce highly inventive and incredibly powerful works that, in themselves, question the possibilities of what poetry could be. What is a poem? Tysdal’s work continues to challenge the idea of simply what is possible.

Published on May 27, 2015 05:31

May 26, 2015

Rita Wong, undercurrent

both the ferned & the furry, the herbaceous & the human, can call the ocean our ancestor. our blood plasma sings the composition of seawater. roughly half a billion years ago, ocean reshaped some of its currents into fungi, flora & fauna that left their marine homes & learned to exchange bodily fluids on land. spreading like succulents & stinging nettles, our salty-wet bodies refilled their fluids through an eating that is also always drinking. hypersea is a story of how we rearrange our oceanic selves on land. we are liquid matrix, streaming & recombining through ingestic one another, as a child swallows a juicy plum, as a beaver chews on tree, as a hare inhales a patch of moist, dewy clover. what do we return to the ocean that let us loose on land? we are animals moving extracted & excreted minerals into the ocean without plan or precaution, making dead zones though we are capable of life. (“BORROWED WATERS: THE SEA AROUND US, THE SEA WITHIN US”)

Vancouver poet Rita Wong’s fourth poetry collection,

undercurrent

(Gibson’s BC: Nightwood Editions, 2015)—following monkeypuzzle (Vancouver BC: Press Gang, 1998), forge (Nightwood Editions, 2007) and sybil unrest (with Larissa Lai; Vancouver BC: Line Books, 2008; New Star, 2013)—is, as Wang Ping informs on the back cover, a “love song for rivers, land, and sentient beings on earth.” Constructed out of lyric fragments, prose poems, memoir notes and extensive research, undercurrentis an extensive pastiche of the story of numerous bodies of water, and our relationships to them. Writing in, around and through the lyric flow, the poems exist, in part, as an extensive call to action against an increasing level of human carnage inflicted upon the earth and its inhabitants: “midway at midway, sun glares plastic trashed, beached, busted / bottle caps, broken lighters, brittle shreds in feathered corpses // heralded by the hula hoop & the frisbee, this funky plastic age / spins out unplanned aftermath, ongoing agony” (“MONGO MONDO”). Unlike a number of other British Columbia poets writing on the dangerous effects of capitalism, Wong’s undercurrent, much like Cecily Nicholson’s From the Poplars (Talonbooks, 2014), allows her subject matter to be the focus, existing not as victim but as robust character, describing a series of affronts, assaults and toxic tales, as well as positive stories on the beauty and power of the undercurrent. As she writes:

Vancouver poet Rita Wong’s fourth poetry collection,

undercurrent

(Gibson’s BC: Nightwood Editions, 2015)—following monkeypuzzle (Vancouver BC: Press Gang, 1998), forge (Nightwood Editions, 2007) and sybil unrest (with Larissa Lai; Vancouver BC: Line Books, 2008; New Star, 2013)—is, as Wang Ping informs on the back cover, a “love song for rivers, land, and sentient beings on earth.” Constructed out of lyric fragments, prose poems, memoir notes and extensive research, undercurrentis an extensive pastiche of the story of numerous bodies of water, and our relationships to them. Writing in, around and through the lyric flow, the poems exist, in part, as an extensive call to action against an increasing level of human carnage inflicted upon the earth and its inhabitants: “midway at midway, sun glares plastic trashed, beached, busted / bottle caps, broken lighters, brittle shreds in feathered corpses // heralded by the hula hoop & the frisbee, this funky plastic age / spins out unplanned aftermath, ongoing agony” (“MONGO MONDO”). Unlike a number of other British Columbia poets writing on the dangerous effects of capitalism, Wong’s undercurrent, much like Cecily Nicholson’s From the Poplars (Talonbooks, 2014), allows her subject matter to be the focus, existing not as victim but as robust character, describing a series of affronts, assaults and toxic tales, as well as positive stories on the beauty and power of the undercurrent. As she writes:after eighty destructive yearsindustrial blockage of salmon habitatwe celebrate this uncanny return in the city:salmon to Still Creek in 2012alert, adept swimmerskindle, perpetuate, astoundwith sleek scaly staminamiraculous as the salmon that grace Musqueam Creekwith each year’s turn around the sunan unbroken vow between relatives

Composed as collage, this is the story of water.

In spring 2014, canoeing in the gentle River of Golden Dreams near Whistler, BC, I fell in when we snagged on a branch and suddenly tipped over. The shock of cold water awoke me into vigilance. Wearing a lifejacket did not eliminate the fear I felt as the river enveloped me completely, reminded me of its power.

Ironically, I cannot swim, though I have taken lessons over the years, and continue to try learning in an on-again, off-again way, as skin and health permit. Having addressed barriers to swimming in the city one by one – finding an ozone-purified pool instead of a chlorinated one, getting prescription goggles, practicing kicks, etc. I have improved but still find myself woefully clumsy and tense in the water, as it conducts so much sound and stimulus, thicker than air. How can someone write a book with and for water, and not swim? Very humbly and respectfully, I would say. It’s not so much that I fear the water, as I fear my own inability to manoeuvre in it, based in part on my reluctance to relax, the resistance to submit to the water’s own dynamics for more than a few breaths. This is partly what I mean when I say that I am still learning water’s syntax. I mean that in a much larger way too, though. One water body flows together with other water bodies, a whole greater than its parts. “What you cannot do alone, you will do together.”

Thanks to the river’s prompting, I will return to the swim lessons when the time and conditions are right. In the meantime, even for those who don’t swim, water rules! Our cities and lifestyles are built upon it, whether we know it or not. Try going a day, or three, without water. Water gives us life. What do we give back to water?

Published on May 26, 2015 05:31

May 25, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Claire Caldwell

Claire Caldwell

is a poet from Toronto, where she also edits Harlequin romances and runs rap-poetry workshops for kids. Her first collection,

Invasive Species

, was one of the National Post's top five poetry books of 2014. Claire was the 2013 winner of the Malahat Review's long poem prize, and she is a graduate of the University of Guelph's MFA program.

Claire Caldwell

is a poet from Toronto, where she also edits Harlequin romances and runs rap-poetry workshops for kids. Her first collection,

Invasive Species

, was one of the National Post's top five poetry books of 2014. Claire was the 2013 winner of the Malahat Review's long poem prize, and she is a graduate of the University of Guelph's MFA program.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Writing and publishing a book was a lifelong dream, so I've been savouring the achievement. Having a book has definitely made me busier with literary things, and I've been lucky enough to travel around Canada and to the States for readings. The opportunity to connect with other poets across the country has been wonderful.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

It's funny; fiction was definitely my first love, as a reader, and I wrote a lot of stories as a kid. I think I came to poetry through the music I listened to in high school—Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Ani DiFranco. And then I read Eliot's "Prufrock" for the first time and was like, "how do I do that?" We had a Collected Poems lying around the house and I read it cover to cover, and after that there was no going back.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

If I'm in the right mood, I can write and shape a poem into its close-to-final form in one sitting. But the "right mood" comes out of a longer, looser process of jotting down notes, reading, taking long walks, letting things percolate.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like to gather images and scraps of lines and let them sit together for awhile. When they start rubbing off on each other, I can usually get going. I take this approach with larger projects, too. Though hopefully the poems I'm working on now will eventually be part of a book, they need some time to get to know each other before they build the house they're going to live in.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I used to get really nervous, but now I love doing readings. I like connecting so directly with an audience. And the more readings I do, the more I "hear" my poems as I write them. I think there's a literal component to voice in poetry--how do the words feel in your own mouth? Also, I often find that poetry readings, whether or not I'm on the bill, can spark creativity. You know when a poet just kills it and the room feels electric? That's contagious, I think.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I'm curious about how poetry can connect people to the world around them in ways other media can't. All these massive, scary things are happening to our planet and it can be hard to grapple with that, emotionally, without just shutting down. I'm trying to figure out how poetry can bridge that emotional gap.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers can have lots of different roles, but I think ultimately writing and reading are acts of empathy. So as long as a drive for connection and understanding is at the heart of what a writer's trying to do, there are endless ways to occupy that space in society.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential! Paul Vermeersch edited Invasive Species, and his sharp eye, keen insights and experienced hand challenged me to make the book better. Maybe I'm biased, since I also work as an editor, but I believe getting an outside perspective from someone who can read your work on its own terms while offering constructive feedback is invaluable.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Kevin Connolly told me, "writing is action." It's both true and a good reminder to stop dicking around.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I've struggled to figure out a consistent routine with a full time job (and a long commute), but I try to carve out weekend mornings and early afternoons for writing. A typical workday usually begins with peanut butter toast and an hour or so of reading on public transit.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I'm stuck, I'll listen to a podcast, start a sewing project, play guitar, work out, bake muffins, clean the bathroom.... Getting away from the blank screen/page for a bit and doing something with my hands usually helps take the pressure off and get thoughts flowing.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My dad's beef stew, a smell I love and miss, though neither my brother nor I eat meat anymore.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Right now, nature and life sciences probably have the biggest influence on my work. As I mentioned above, music was my gateway drug into poetry. At various times, visual artists like William Kurelek, Georgia O'Keefe, David Blackwood, Joseph Cornell and Tom Thomson have also influenced me.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

One of my most beloved poems/performances is this recording of bpNichol reading "Friends as Footnotes," from The Martyrology.

There are too many writers to name, working in poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction, but here are a few: Dara Wier, Sue Goyette, Elizabeth Kolbert, Roxane Gay, Jenni Fagan, Claudia Rankine, Dorothea Lasky, Galway Kinnell, Karen Solie.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a book for kids.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I had more of a mind for hard data, I'd love to be some kind of scientist/biologist--maybe an animal behaviourist. I love the idea of working outside, and I spent many summers at a canoe tripping camp, so being a wilderness guide could also be appealing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I did all kinds of arts as a kid, and by high school I had narrowed things down to fine art, music and writing. I was pretty good at drawing and playing guitar, and I still love both, but for whatever reason, when I tried to create original work in either medium I got stuck. Writing came naturally, so I stuck with it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I'm in the middle of Kenneth Koch's Rose, Where Did You Get that Red? It's a really inspiring and insightful book about teaching poetry to kids. The last great film I saw was Timbuktu , a feature about the Islamist occupation of that city/region. One thing I loved about that film was the treatment of subtitles. So many different languages are spoken in the film, but not every character understands every language, and depending on the POV of each scene, certain lines aren't translated for the viewer, either.

19 - What are you currently working on?

A smattering of poems, just trying to gain steam after a hectic winter. Since it's poetry month, I'm following along, somewhat, with the daily NaPoWriMo 2015 prompts for inspiration/motivation.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on May 25, 2015 05:31

May 24, 2015

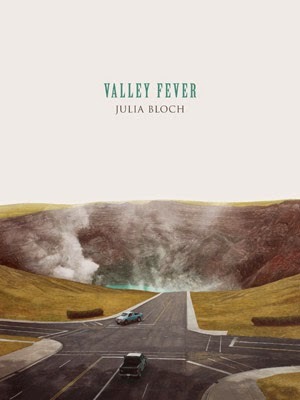

Julia Bloch, Valley Fever

ALLISON CORPORATION

Outside the city is a thick line of thinkingand outside that line of thinking is a stripof water and outside that strip of wateris a muscle. Lengthen the muscle.Show restraint and perfect tension. That isAllison Corporation.

California is not new.California is not new.California is not new.

This is a poem for you for youfor spontaneous flightBecause we live underneath some helicopters.

I’m rewriting the plan.I’m rewiring the plan.

And outside that muscle is fat and boneand a car that carries the body elsewhere.

We love the drones.We love that they all have heads andarms to fight with. All theirarms are united. You were notborn in California but neither was I.I am angling at the surface larger

than your actual face, a notcorporate body. This is a love poemand I did not do any research.

Philadelphia poet, critic and editor Julia Bloch’s eagerly-awaited second poetry collection is

Valley Fever

(Portland OR/San Francisco CA: Sidebrow Books, 2015), a book that appears three years after the publication of her

Letters to Kelly Clarkson

(Sidebrow Books, 2012). There is a precision to Bloch’s dense lyrics that is quite compelling, one that is constructed out of an accumulation of sharp sentences that accumulate, despite the appearance of narrative disjunction that exist between those sentences. As she writes to open the poem “FOURTH WALK”: “Don’t believe in writing as possession. Don’t / believe in bylines like slimming wear.” It is as though the sentences in her poems less leap from point-to-point than somehow float across and even through their own trajectory, seamlessly incorporating a wide array of ideas and fragments together into a single thread. As she writes to open “VISALIA”: “An allergy to / bone, this weather. / That’s how deep.”

Philadelphia poet, critic and editor Julia Bloch’s eagerly-awaited second poetry collection is

Valley Fever

(Portland OR/San Francisco CA: Sidebrow Books, 2015), a book that appears three years after the publication of her

Letters to Kelly Clarkson

(Sidebrow Books, 2012). There is a precision to Bloch’s dense lyrics that is quite compelling, one that is constructed out of an accumulation of sharp sentences that accumulate, despite the appearance of narrative disjunction that exist between those sentences. As she writes to open the poem “FOURTH WALK”: “Don’t believe in writing as possession. Don’t / believe in bylines like slimming wear.” It is as though the sentences in her poems less leap from point-to-point than somehow float across and even through their own trajectory, seamlessly incorporating a wide array of ideas and fragments together into a single thread. As she writes to open “VISALIA”: “An allergy to / bone, this weather. / That’s how deep.” Bloch’s short lyrics have an incredible compactness. To call her poems “quirky” or even “surreal” might do them a disservice, but both elements exist in Valley Fever, alongside a deep earnestness, a wry self-awareness and an engaged critique of everything she observes. As she writes to close the poem “UNSEASONAL”: “Once someone said love / turned off like a faucet. // I didn’t want this / to be that kind of party.”

HOSPITALIST

New definitions ofdoing poorly dewingup on the face.Not always facing up,not always awareof corners, sadand lite-jazzy.Aristotle saysthought by itselfmoves nothing. No onedecides to have sacked Troy.All the sounds are in miniaturebut the room is largein ruined light.

Constructed as a collection of short lyrics, Valley Fever presents a curious shift from the epistolary poems that made up her first collection, Letters to Kelly Clarkson. Given the book-as-unit-of-composition element of that prior work, it is tempting to read this new book not as a grouping of stand-alone poems but as a thoughtfully-conceived single work, and perhaps the real answer might be that this exists as a combination of the two. Somehow, her poems encompass an expansive curiosity, a healthy distrust of what she sees and knows, and manage to include just about anything and everything you can imagine, in a series of poems sketched as notes towards understanding how it is one can live, and be, better in the world. As she ends the poem “RIGHT OVARY, LEFT OVARY”: “I want to know all the things. / I want to know all the gods.”

LISTENING TO PAUL ZUKOFSKY PLAY PHILIP GLASS

On Locust Street with its low stepsI thought I saw a pastel hotelsettle its elbows onto the walk.When I talk to you sometimes my tonguebubbles out of my mouth—I wantedto say forth but it doesn’t march, it startsand stops. The mouth rooted and frothy, litwith an everyday flavor. The string skips. PaulZukofsky’s violin stutters. L. says a waynot to feel nervous is to look at the eye.Hopefully there is a salted sea when youlook there. Horses marchingunder their hands. It’s nevergoing to happen.

Published on May 24, 2015 05:31

May 23, 2015

Oana Avasilichioaei, Limbinal

The lines were drawn without our consent. This is an empty statement, for the drawing of the lines did not require our consent. We shored the river but turned away when we realized our subjectivities were seeping into it. We fought unfairly. Overgrown like wedges of land covered in weeds. With our jugular appendages, we intoned coarse sounds. Ventured to look past our moss-ridden thighs. Mostly, our soundings were futile, husked. But there were moments of lucidity, even resonance. Then our hands would reach out to touch each other’s throats as though in recognition. Or acknowledgment. Petals of thought blew gusts around us. Small creatures guarded our solitudes. Which churned in the cavern of our guts. The vastness of our intention was a material we could not fathom. We asked questions that had no answers and as such perpetuated into quarries of language. (“Line Drawings”)

Montreal poet and translator Oana Avasilichioaei’s new collection, Limbinal (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2015), is built as a series of lyric explorations of borders and partitions, attempting to articulate the no-man’s land between fixed ideas, solid objects and a variety of poles, from geography to genre, even moving into footnotes and beyond, into the margins themselves. As she writes near the beginning of the opening section, “Bound”:

The geography keeps shifting into bloom and decay, thus daring to future. Periphery disrupts the dialogue. Floundering, wet lines linger. Fish bend the river into its undulations, spring curves. Will these trajectories double back, mislead us? We leave unnoticed through a back gate to make a country elsewhere. We pass the perennials and smile softly. What is our spatialized intention?

The author of four previous poetry collections— Abandon (Toronto ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2005), feira:a poempark (Toronto ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2008), Expeditions of a Chimæra (with Erín Moure; Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) and We, Beasts (Wolsak & Wynn, 2012)—as well as five translations, Avasilichioaei’s work has evolved into a series of inquiries on how and where multiple sound, language, meaning and ideas overlap, shift and blend, allowing the borders to shimmy and bleed, and somehow illuminate the differences through highlighting the similarities. Her prose is incredibly fluid, even liquid, managing to easily flow and shape itself around a variety of thoughts and ideas.

Silken Shore

Lake asleep in a dusking leaf, the hair of a peasant I killed awaits to strangle me. Its ridicule on this final step feverishly summoned, the mane’s adroitness won’t pass down to my successors.

I am a flamed wheel, visible to those who have enemied me for a long while.

Somewhere, in the pleasure of the great distance, a vaporous flag ascends and descends; soldiers bloody their nakedness, hands grasping convulsively; sky, unused to incidents of this kind, blooms too soon.

We can’t expect hospitality, though we wear melancholy’s gloves. We trench in, we are the despotic fanfare of a blind platoon. We refuse sleep.

Tears march embittered through the snows. We watch them approach, soldier the urge to run off with a shadow, this night on the eve of a new flag.

Constructed in ten sections, the book includes “Itinerant Sideline,” a section composed entirely of photographs, highlighting Avasilichioaei’s engagement with the between-space, and the space that connects two opposing or conflicting spaces. A further section, “Ancillary,” is a translation of the only poems Paul Celancomposed in Romanian, composed between 1945 and 1947, during Celan’s own evolution. As part of her notes at the end of the collection, Avasilichioaei writes: “[…] Paul Pessach Antschel became Paul Celan during his years in Bucharest, having first attempted to translate himself into Paul Aurel and Paul Ancel. Written in one of his adopted languages, in the desolation of the war, a war he survived in a Romanian labour camp while his family died in another, these poems are thresholds, existent and impossible, invented and possible. Limbs disarticulate and wander their syntax in the estranged language, lose control of their articulations, stir in the aftermath of an inhumane civilization.”

Constructed in ten sections, the book includes “Itinerant Sideline,” a section composed entirely of photographs, highlighting Avasilichioaei’s engagement with the between-space, and the space that connects two opposing or conflicting spaces. A further section, “Ancillary,” is a translation of the only poems Paul Celancomposed in Romanian, composed between 1945 and 1947, during Celan’s own evolution. As part of her notes at the end of the collection, Avasilichioaei writes: “[…] Paul Pessach Antschel became Paul Celan during his years in Bucharest, having first attempted to translate himself into Paul Aurel and Paul Ancel. Written in one of his adopted languages, in the desolation of the war, a war he survived in a Romanian labour camp while his family died in another, these poems are thresholds, existent and impossible, invented and possible. Limbs disarticulate and wander their syntax in the estranged language, lose control of their articulations, stir in the aftermath of an inhumane civilization.”Poem for Mariana’s Shadow

Love’s mint grown like an angel’s finger.

You must believe: from the soil sprouts an arm twisted by silences,a shoulder scorched by the glaze of smothered lightsa face blindfolded with the black sash of sighta large leaded wing and a leafed onea body wearied by rest soaked in waters.

Look how it floats amid the grasses with outstretched wings,how it mounts the mistletoe stairs towards a glass house,in which, with enormous steps, rambles an aimless seaweed.

You must believe this is the moment to speak to me through the tears,to go there barefoot, be told what awaits us:mourning drunk from a glass or mourning drunk from a palm—and the maddened weed falling asleep hearing your answer.

Colliding in the dark the house’s windows will clamourtelling each other what they know, but without discoveringwhether we love one another or not.

Published on May 23, 2015 05:31

May 22, 2015

Profile on Chuqiao Yang, with a few questions

My profile on Bronwen Wallace Award shortlisted poet Chuqiao Yang, with a few questions, is now online at Open Book: Ontario. Good luck! The winner will be announced tomorrow.

My profile on Bronwen Wallace Award shortlisted poet Chuqiao Yang, with a few questions, is now online at Open Book: Ontario. Good luck! The winner will be announced tomorrow.

Published on May 22, 2015 05:31

May 21, 2015

Pete Smith, Bindings with Discords

Evensong [Coventry Cathedral]

In this place, this slow mausoleumspace held by cold stone & glassangles criss-crossinto shiftingopen-occult wings.Where sunlight strikesair bleeds multi-coloured psalmsand when, in service, the choral voiceraises William Byrd, featheredquavers trace the arcing roof,fana rainbow of harmonic hopethen fall to ground, flame-tongued.Profound expectations fibrillatethe hearts of the faithful. Some glimpsedoors in stone & burning air beyond; somefixate on the eagle rootedto the lectern’s edge, freedom tetheredin its held wing,law nailedin itsclaw

Kamloops, British Columbia poet Pete Smith’s latest offering is Bindings with Discords (Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2015), a book uniquely influenced by British experimental poetry as well as a variety of Canadian writers, especially those around the Kootenay School of Writing. Born and raised in England, Smith emigrated to Kamloops in 1974, where he was able to slowly start interacting with a number of Canadian poets and their works. As he writes as part of an interview forthcoming at Touch the Donkey :

In Britain, no direct engagement beyond being a consumer of mags which provided different sets of outlook: Stand– toward Europe largely; Agenda – Poundian modernisms; Grosseteste Review– openings toward USA, combo of projective & objective ‘schools’ filtered through a very English light.

Attended readings at the then Cariboo College where I heard but didn't ‘meet’ Birney, Newlove, Bowering et al. (A long parenthesis, 10 to 15 years, takes me into a North American cult/church community where I become an elder & preach regularly – until finally reading my way out of that wilderness – picking up while there some useful self-discipline for essay writing & a preachiness in my poems that I have to guard against).

Real connections began on three fronts in the 1990s: firstly, through the Internet & an email I sent to Nate Dorward I connected up with British & Irish poets I felt at home with & led to the publication of the first Wild Honey Press chapbook; through Nate again I learned of a reading at the ksw whose venue I failed to find then but, thanks to Rob Manery, found it for the next time; the Kamloops Poets Factory where Warren Fulton’s energies created a local scene & we brought in some good writers to read & conduct workshops (my contributions were all through the ksw connection: Mike Barnholden, Aaron Vidaver, Ted Byrne on one occasion; Lissa Wolsak & Lisa Robertson on Easter Sunday, 2000 – Lisa read from The Men. Not so many personal meetings really, lots of recruits I bring in from my reading, not in order to name-drop, but to share my experience in a particular text-world. Exploration & celebration.

Smith’s poems favour a kind of narrative and tonal discord, pounding sound against meaning and sound in a way reminiscent of some of Ottawa poet Roland Prevost’s recent writing. As Smith writes in the poem “From the Olfactory”: “Swamped by irritants / air-borne and scoped / he defended a weakened immune / system, set about mopping up / incontinent emotions, / secured HQ in the lachrymal ducts.” Composed over a period of some twenty-plus years, the collection is constructed into two groupings each made up of three sections: “Part One: Pointes & Fingerings,” that includes “One-Eye-Saw: ‘in the sure uncertain hope,’” “20/20 Vision” (an earlier version of which was produced as a chapbook through Wild Honey Press in 1998) and “Evacuation Procedures,” and “Part Two: Three Fancies in the Key of BC,” which includes “Strum of Unseen” (an earlier version of which was produced as a chapbook through above/ground press in 2008), “48 Out-Takes from the Deanna Ferguson Show” and “Mother Tongue: Father Silence.” Perhaps due to the extended composition of the collection, Smith’s variety of structures holds the book together incredibly, shifting his punctuated collage-works from short fragments to prose poems to poems that break structure down altogether. Interestingly enough, Smith’s writing comments on the visible absence his writing creates, as he publishes quietly, nearly invisibly. In “48 Out-Takes from the Deanna Ferguson Show” he writes: “Let me introduce you to my anthology. Your absence will guarantee you pride of place.”

Smith’s poems favour a kind of narrative and tonal discord, pounding sound against meaning and sound in a way reminiscent of some of Ottawa poet Roland Prevost’s recent writing. As Smith writes in the poem “From the Olfactory”: “Swamped by irritants / air-borne and scoped / he defended a weakened immune / system, set about mopping up / incontinent emotions, / secured HQ in the lachrymal ducts.” Composed over a period of some twenty-plus years, the collection is constructed into two groupings each made up of three sections: “Part One: Pointes & Fingerings,” that includes “One-Eye-Saw: ‘in the sure uncertain hope,’” “20/20 Vision” (an earlier version of which was produced as a chapbook through Wild Honey Press in 1998) and “Evacuation Procedures,” and “Part Two: Three Fancies in the Key of BC,” which includes “Strum of Unseen” (an earlier version of which was produced as a chapbook through above/ground press in 2008), “48 Out-Takes from the Deanna Ferguson Show” and “Mother Tongue: Father Silence.” Perhaps due to the extended composition of the collection, Smith’s variety of structures holds the book together incredibly, shifting his punctuated collage-works from short fragments to prose poems to poems that break structure down altogether. Interestingly enough, Smith’s writing comments on the visible absence his writing creates, as he publishes quietly, nearly invisibly. In “48 Out-Takes from the Deanna Ferguson Show” he writes: “Let me introduce you to my anthology. Your absence will guarantee you pride of place.”one: desire & music are a vortextwo: the rhythm the rhythm the rhythmthe rhythm three: dithyrambiccelebration collapsebottom fish sit this one outon top of the newsfour: slow dance among the picnic debrislives measured out in stepsportraits of soles on the move & at restwaltzing through wilted lettuce crusts of cheese crumbed stones of breaddancing away from stilled life (“Third Movement”)

There’s an incredible density to Smith’s work, one that comes across as a narrative collage, excising unrequired words for something built as both incredibly precise and remarkably open to a variety of possibilities. In his review of the Wild Honey Press edition of 20/20 Visionfor The Gig, Nate Dorward wrote:

The wit catches the ear: not the deadpan standup comedy sometimes the fate of the New Sentence, but a mode of inquiry into poetic style and into cultural authority. There’s a wish to avoid “the poet shrunk to a witness”, reproducing the personal, religious and social nostalgias on offer: “technes create / instant nostalgia, break you and your dear ones / into timed fragments: zoom, smile, cut; / in your pram with soother, in your graduation / gown, in your senile frame with demented smile.” High prophecy may be unavailable, but one can be “eloquent” in “disbelief” […].

There is much going on here, in a poetry that builds upon responses to writers, writing and artwork, including photographer Fred Douglas, poet Deanna Fergusonand the late poet, artist and musician Roy K. Kiyooka. Binding, as he tell us in the title, with discords: one can’t be any more direct than exactly that.

Bamboo-heart, water-heart teach us the meanings of friendship. Between heaven and earth, a journey to share – everyday home. Be with until public law – BC Security Commission, March 4 1942 – states you are decreed nisei, sundered by stained metalblade of fear-hatred-greed. “Relocatable persons” are asked to be rootless, artless, homeless &, best self, lifeless. Everyday home claps you into its pure bamboo, empty water jail. Be your own best friend – a shade yellow, simulacrum/b of white (boss) man – bereft of former chums.

claw metal clap (“Mother Tongue: Father Silence)

Published on May 21, 2015 05:31

May 20, 2015

12 or 20 (second series) questions with TC Tolbert

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. The author of

Gephyromania

(Ahsahta Press 2014),

Conditions/Conditioning

(a collaborative chapbook with Jen Hofer, New Lights Press, 2014)

I: Not He: Not I

(Pity Milk chapbook 2014),

Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics

(co-editor with Trace Peterson, Nightboat Books, 2013), spirare (Belladonna* chaplet, 2012), and

territories of folding

(Kore Press chapbook 2011), his favorite thing in the world is Compositional Improvisation (which is another way of saying being alive). S/he is Assistant Director of Casa Libre, faculty in the low residency MFA program at OSU-Cascades, and adjunct faculty at University of Arizona. S/he spends his summers leading wilderness trips for Outward Bound. Thanks to Movement Salon and the Architects, TC keeps showing up and paying attention. Gloria Anzaldúa said, Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks. John Cage said, it’s lighter than you think. www.tctolbert.com

TC Tolbert often identifies as a trans and genderqueer feminist, collaborator, dancer, and poet but really s/he’s just a human in love with humans doing human things. The author of

Gephyromania

(Ahsahta Press 2014),

Conditions/Conditioning

(a collaborative chapbook with Jen Hofer, New Lights Press, 2014)

I: Not He: Not I

(Pity Milk chapbook 2014),

Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics

(co-editor with Trace Peterson, Nightboat Books, 2013), spirare (Belladonna* chaplet, 2012), and

territories of folding

(Kore Press chapbook 2011), his favorite thing in the world is Compositional Improvisation (which is another way of saying being alive). S/he is Assistant Director of Casa Libre, faculty in the low residency MFA program at OSU-Cascades, and adjunct faculty at University of Arizona. S/he spends his summers leading wilderness trips for Outward Bound. Thanks to Movement Salon and the Architects, TC keeps showing up and paying attention. Gloria Anzaldúa said, Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks. John Cage said, it’s lighter than you think. www.tctolbert.com1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I grew up Pentecostal.

The Holy Spirit would sometimes send people running up and down the aisles (unclear if they were pursuing or being chased), it might make their bodies convulse. There was a kind of inspired and terrifying celebration that undulated between laughter, pleading, weeping, and cheers. But those most filled with God could be identified by how they were filled with language. To speak in tongues was to be spoken through – a language both intensely private and necessarily shared – glossolalia – a kind of benevolent wildfire on the tongue – to receive the most excruciating, exquisite untranslatable articulations as a gift.

I suppose I came to poetry first to speak my body out of and into existence. I write to speak in tongues and to prophecy. To know something I can’t know. To surrender. To be a good-bad body written into. To be read. To be a good-bad body gone bad-good.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

In Queer Space, Aaron Betsky says, we make and are made by our spaces. In this way, where I read a poem (and by where I mean the physical location - which includes the architecture and the bodies the poem interacts with and the spaces made by the poems around it) shapes how I read the poem. And since I also believe what Stein said (There is no such thing as repetition. Only insistence.), every reading is different. And so I don’t think of them as readings, so much, because I think that implies something stable about the text that I want to avoid. I get much more excited about what can happen when people gather in a room and trade noises. I absolutely love the collaborative process of showing up. Of creating installations.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In the early 70’s, gay and bisexual men began using a hanky code to signal to other men what they were into (SM, fisting, oral, anal, etc), what they were looking for (tonight I want someone to hold me, or would anyone be willing to piss in my mouth?), and how they identify (bottom, top, or switch). This is known as flagging. Not only a way to clarify and communicate desire, but a public acknowledgment of a possibly dangerous combination of attraction and identity hidden in plain sight (queerness was, and often still is, met with social and individual violence). As a trans and queer writer, I say. And then: this is different, I think, than a writer who happens to be trans or queer. I am particularly interested in flagging and how this relates to language, audience, and accessibility. Can the subversive still be subversive if it passes into the realm of widely legible? How do we share the obscured, public confession? How are intimacy, desire, and connection wielded in common space? What passes as a body? What is the desire of form? What does it mean to be out?

Pema Chodron says, Everything that human beings feel, we feel. We can become extremely wise and sensitive to all of humanity and the whole universe simply by knowing ourselves, just as we are. How passing, for me, can be both a protection from violence and can perpetuate violence. A necessity and necessarily enigmatic. I write to experiment with passing, with being a self I can know, with flagging, with turning on. I think of the textual body as a gendered body. My trans(gender) body is an unreliable text. The narrative is ruptured. Trust may be built or it may be broken. The veneer of coherence and safety completely gives way. Kathy Couch says there is a difference between props and objects. She says, prop is a shortened form of property and we never expect our property will teach us anything. A poem isn’t exactly a performance. I hope it’s not a prop, either. But there’s an audience. And I worry about showing off instead of showing up. A reckoning with the ambivalence of form. And people are objects, too. Surrender and struggle with constraint.

As a body in a person, as a poet, as these lines in this order – white skin and male passing privilege, breasts I used to bind but no longer want to, soft belly, hips that could easily carry children but never will, facial hair that refuses my jaw while absolutely flourishing on the underside of my chin – I’m continually interested in the architecture we find ourselves in. At what point does construction become didactic? What is the space between container and constraint? What happens when we try, and is it possible, to subtract formula from form?

Also, there is generosity. And this is different, I think, from being nice. I want my work to be inhabited by vulnerability, experiment, risk. I want to be visible. A kind of accessibility that has more to do with being encountered than being understood. I want collaboration. And failure. And delight.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

For me, the worst that could happen to poetry would be that any given poet’s work (whether it be poems, criticism, or some combination there of – I inherently consider poetry to be political and personal, even though I recognize the shortcoming in that) the worst that could happen would be for poetry to end at the page. How do we compose in the moment? If attention is action? If one wants to undermine systemic violence, racism, capitalism, and/or compulsory heterosexuality through syntax or some other poetic project, one shouldn’t be a dick in real life.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve encountered challenges with everything I truly care about. It’s an incredible gift to be read closely, carefully. I’m blessed. I’ve experienced all of these things.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“I know I’m in real trouble when I start to judge my insides against someone else’s outsides.” – said to a friend in Chattanooga at an Al Anon meeting.

Annie Dillard said: “How you live your days is how you live your life.”

John Cage said: “It’s lighter than you think.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (your own poetry to collaboration)? What do you see as the appeal?

Relatively easy, I suppose, in that I genuinely think of genre as gender. I’m not a theorist, or rather, critique is just my affection in drag. For a few years now I’ve been working on a series of lyric essays in which I am writing my body into existence though not necessarily through content. I’m looking for a textual body expansive (and constrictive) enough to inhabit. I want to live (t)here. For now, I find that space in hybrid forms. Utilizing elements of poetry, research, and personal narrative, I think of these essays as embodied meditative investigations on the trans body – my trans body – and its relationship to architecture, intimacy, and public space. They are, to me, genderqueer bodies, much like my physical genderqueer body – nonlinear, dynamic, a kind of textual bricolage, sometimes awkward or halting, passing as narrative at one turn, then full of ruptures in logic, vulnerable and visible and joyously so.

I not only think of the lyric essay as an assemblage in artistic terms (utilizing some found text and placing it in new contexts) but also as an extrapolation of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of assemblage and “nomad thought” as open-ended - that parts of one body can be placed in a new body and still function. I’m especially curious about order and organization, when a piece of text is relevant, which component parts impact the entire body. When is the range of motion extended (or impacted) by relationship? What is a component part? What is a (w)hole?

I definitely think of these pieces as collaborative. I need you to help me make sense of them. This is similar, I think, to how we collaborate to create meaning from each of our gender expressions and identities, trans or not. But public space is often a dangerous place for trans and genderqueer bodies (most specifically and brutally, the bodies of trans women of color): what could be collaboration, or celebration, becomes violence, oppression, and control. My hope is that reading (and writing) these essays is a practice in shifting that dynamic. That we can play, be curious, wander among tangents, delight in the previously undefined, decorate, find connections where they are not obvious, unhinge our expectations, say yes to what we don’t yet know, investigate the relationship between proof and prose.

In this way, I want to celebrate trans and genderqueer bodies – how we pass and sometimes don’t, how we spill over, slip, call out, miss the point. Much like J. Halberstam, I believe failure on one level creates a grammar of possibility on another. But this failure is different, I think (I hope), from being sloppy. Or careless. Or lazy. Lisa Kraus, a dance critic and former dancer with Trisha Brown, says that rigor is no longer about the pointed foot but about the precisely timed collision, the exact harnessing of weight falling through space. These essays, I’m afraid, won’t defend anything or even prove a good point. They bump into things. They might make illegible what was just starting to come into focus. The appeal is that they are rigorous in their failure – I hope.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Right now my days aren’t nearly as regularized as they have been at other times in my life. (That’s both true and not true.) My days begin with a banana and peanut butter. And that’s how they’ve begun since 2002.

For 5 years I would get up every morning and do my “morning pages” based on The Artist’s Way . Like so many constraints, this practice taught me the kinds of boundaries I need to feel safe enough to let go.

(I might be in a period of letting go.)

(I might always be in a period of letting go.)

(To always be anything may be a way of not letting go.)

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I get out of my own way and get out in the world. I get off the internet. I go for a hike.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Icy hot. Salmon patties. Mentholatum rub.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Modern dance. The body. The body in relationship. The body in nature. Architecture.

The Architecture of Happiness, Alain de Button says: The significance of architecture is premised on the notion that we are different people in different places and on the conviction that it is architecture’s task to render vivid to us who we might ideally be. I look at my house, my relationships, the things I’m writing, my body. These are synonyms. And I wonder how non-trans people (and other trans people) experience these things. Is your body an architecture? Is your name? What are you constructing now? Can you visit it, and therefore, can you leave?

Also: Compositional Improvisation (which is different from, although related to, Contact Improvisation). (Although neither of these are comedic improv, all three are grounded in the practice of paying attention to exactly what is happening right now and figuring out how to say yes.)

Compositional Improvisation (a phrase coined by Katherine Ferrier and the Architects) explores intersections of text, body, architecture, space, collaboration, and attention in order to expand the range of what is possible for composition – specifically composition with the body. I think of all of this as just another way of saying “being alive.” It is built on the chance, (Soma)tic, conceptual, and collaborative techniques of poets, dancers, and musicians from the last 60 years and emphasizes composing (individually and collaboratively) in the moment to create dynamic, rigorous, complex, and fully realized pieces without rehearsal or planning.

For me, it’s a practice in embodied consciousness that is experimental, risky, playful, vulnerable, and radically open - an opportunity to experience Jack Halberstam’s “queer art of failure” (as if I somehow don’t have enough of that in my life!).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

All of them. I mean that.

The fact that people write, and dance, and put paint on things, and grow gardens, and create exquisite compositions out of a few vegetables and grains (I know absolutely nothing about food). That fabrics are dyed. Stones are laid side by side and rooms are arranged. Re-arranged. That there is singing.

I’m housesitting for a friend right now and all I can see when I look over my computer screen is 5 pieces of telephone pole stood upright – no longer useful for keeping words off the ground but somehow this little pile of desert sand is now a yard.

Malebranche said that Attention is the natural prayer of the soul and as long as something singular can become multiple, I feel ok about the world. CA Conrad is right: It’s all collaboration. I need all of these others to collaborate.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Honestly, I’m both audacious and naïve enough to attempt just about everything I’ve wanted to do. That doesn’t mean I always get it right, just that I’m fool enough to try. I’m happy to sleep in my car and/or camp all summer if it means I can go wherever I want to go. And so I do. Most of my “to do list” is more interpersonal right now – practice more intimacy, ask for help when I’m scared, be more vulnerable with my mom and dad, stop trying to prove my self worth all the time, let myself be seen...

I hiked the Appalachian Trail in 2001 (yep, all of it, with my dog, Isabella) and I’d like to do another long trail. I’d like to run a marathon. I’d also like to travel internationally but I’m not that interested in being a tourist so I’m still trying to figure out how to navigate that desire. I like doing things that scare me. I recently fell in love again and it had been almost 4 years since I dated anyone so this feels scary and exciting. (and may be small.) (but also may be huge.)

One time, when I was on staff training for Outward Bound, we did this reflective activity where we had to identify our gender, race, religion/spirituality, sexual orientation, name, and one life goal. Then we had to give up one of those identities. Then another. Then another until we were left with just one identity. In my life goal section I had written, “publish 3-5 books.” I got rid of that rather quickly. The thing I couldn’t part with was my name. But that wasn’t true for anyone else. For them it was “to be happy” which, as it turned out, was a completely allowable life goal.

I want my life to be meaningful. I want to contribute to more tangible and intangible goodness in the world.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

My first answer would be a dancer. I also always wanted to be on Broadway. But I think I’m cheating. When you say, “what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?” I think you are asking me to consider what would I do if my art were more objectively measurable.

I’d be a doctor for Doctors Without Borders. Or I’d help build houses for Habitat for Humanity. My life isn’t over so I still may do one. Or both.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Well, I tried to do something else. I mean, I was in my last year of undergrad getting a degree in English Education – I was just about to start student teaching and was well on my way to becoming a high school English teacher. It was 1998 and I was a 23-year-old white, Pentecostal woman. I was married to a pretty great guy and I was about to become the first person in my family to earn a college degree. Still living in my hometown - Chattanooga, Tennessee - I had never really spent time outside of the south.

That spring I took a feminist theory class. Even though it wasn’t a required text, my professor gave me her copy of This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color . In my first poetry class, we read the poem “Fiddleheads” by Maureen Seaton. Both This Bridge and “Fiddleheads” did something with language that I needed. They exhilarated me. Made me feel less alone. These were women’s voices, queer voices – marginalized and fierce. They held me accountable. Showed me how silent I was becoming (had become, had been forced to become, had been expected to become).

Both of these said: OPEN YOUR FUCKING MOUTH.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Citizen by Claudia Rankine and New Organism: Essais by Andrea Rexilius.

I wish I watched more films than I do. I don’t know if this is a great film but it’s a film I can’t stop thinking about – particularly the opening sequence – Melancholia , directed by Lars von Trier.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Becoming better friends with god.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on May 20, 2015 05:31

May 19, 2015

Tour de blogosphere: A Special Guide to Ottawa’s Literary Blogs : rob mclennan

Catherine Brunelle of Apt613 was good enough to write an article spotlighting a bunch of my online activity, including

Touch the Donkey

, above/ground press,

seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics

,

ottawater

, the

ottawa poetry newsletter

, Chaudiere Books, dusie and the ottawa small press book fair. Thanks much!

You can find the original article here

.

Catherine Brunelle of Apt613 was good enough to write an article spotlighting a bunch of my online activity, including

Touch the Donkey

, above/ground press,

seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics

,

ottawater

, the

ottawa poetry newsletter

, Chaudiere Books, dusie and the ottawa small press book fair. Thanks much!

You can find the original article here

.

Published on May 19, 2015 05:31