Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 353

February 23, 2016

Queen Mob's Teahouse: Mary Kasimor interviews Ann Tweedy

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the fifth interview is now online: an interview with Ann Tweedy, conducted by Mary Kasimor. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, and an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter.

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the fifth interview is now online: an interview with Ann Tweedy, conducted by Mary Kasimor. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, and an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter.Further interviews I've conducted myself over at Queen Mob's Teahouse include conversations with Allison Green, Andy Weaver, N.W Lea and Rachel Loden.

If you are interested in sending a pitch for an interview my way, check out my "about submissions" write-up at Queen Mob's ; you can contact me via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com

Published on February 23, 2016 05:31

February 22, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sarah Mian

Sarah Mian’s

debut novel,

When the Saints

, was published by HarperCollins in 2015. Her award-winning fiction and poetry have appeared in journals such as The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review and The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction. Her non-fiction has been featured in Flare Magazine and on CBC Radio’s ‘Definitely Not the Opera’ and ‘How To Be.’ Sarah is from Dartmouth, NS and now lives on Nova Scotia’s south shore.

Sarah Mian’s

debut novel,

When the Saints

, was published by HarperCollins in 2015. Her award-winning fiction and poetry have appeared in journals such as The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review and The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction. Her non-fiction has been featured in Flare Magazine and on CBC Radio’s ‘Definitely Not the Opera’ and ‘How To Be.’ Sarah is from Dartmouth, NS and now lives on Nova Scotia’s south shore.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Having my first novel published by HarperCollins was a dream come true. Walking into a Chapters and finding my book on the shelf gives me a profound sense of accomplishment. A few days after the book was a published, a three-quarter page review appeared in the Toronto Star endorsing it as a contender for Canada Reads.

When the Saints is raw and hard-edged, a drastic departure from the saccharine starter novel I penned in my twenties. I’ve been overwhelmed by the response to it from across the country. Everyone tells me the fictional setting of Solace River is their hometown.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I have a compulsion to make up stories and I hate doing research, so fiction is the perfect medium.

I wrote poems for many years but ultimately decided that there are writers who are better at it than I am. Great poets don’t presume they can moonlight as fiction writers and I think fiction writers should give poets the same respect.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I usually start with the seed of an idea. Once I’ve gotten to know my characters, they take over and start gunning it down all sorts of back roads and alleys I didn’t know existed. That’s when I know the writing is good; when I’m in the bitch seat.

The first draft of When the Saints was a sprint to the end, almost like my character needed to spill her whole bugged-out story over one beer. Then I had to get her to start over and fill in the gaps. Six years later, I finally had all the pieces to the puzzle.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

When the Saints started as a piece of flash fiction that turned into a short story that turned into a novella that became the novel it was always meant to be.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love to perform, so I enjoy author readings, but it’s not a very interactive experience. Meeting with book clubs is more useful since I get to connect with individual readers and hear about what worked and didn’t work for them in an intimate setting.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

When the Saints asks why some people who grow up in dysfunctional families manage to transcend their circumstances while others are unable to break the cycle.

With my new novel I’m questioning, amongst other things, whether there is life after death.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I’m borrowing from friend and fellow writing group member, Stephanie Domet, who said it brilliantly when she told me that people are asleep and the artist’s job is to go around poking everyone awake.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s absolutely essential to have other hearts and minds collaborate on a manuscript. I haven’t had the experience of dealing with a difficult editor, but I welcome the challenge of working with someone who has an incompatible set of values and assumptions.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

While I was at the Banff Centre working on When the Saints, esteemed author Greg Hollingshead told me not to rush it, that a writer’s first book has the potential to make or break their career. I spent about four years heeding his advice which means that, in total, it took me seven years to write my novel (minus bathroom breaks.)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I have written poems, plays, songs and screenplays, performed in radio and acted in community theatre. All of these mediums have strengthened my creative muscles and made me a better storyteller.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have a day job, so I perform a very delicate dance all day in which I minimize the file on my computer screen every time someone walks by so no one can see what I’m actually doing.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I notice that I often have epiphanies about plot while I’m performing a repetitive physical activity like jogging or swimming. I think it’s because my mind is quiet and I can listen to my intuition.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The fresh salty ocean air. I live a stone’s throw from the beach.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My fiancé and I have over 600 vinyl records and I recently made the discovery that we experience music very differently. He’s primarily focused on instrumentation while I’m lost in the lyrics. I once wrote an entire short story collection in which each tale was based on a Canadian folk song.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

These works (amongst others) have changed my life:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Frederick Douglass), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll), Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Henry David Thoreau), “anyone lived in a pretty how town” (E.E. Cummings), “Desiderata” (Max Ehrmann), On the Road (Jack Kerouac), Night (Elie Wiesel), Franny and Zooey (J.D. Salinger), “The Swimmer” (John Cheever), Lives of Girls and Women (Alice Munro), “The Lesson” (Toni Cade Bambara) and any song ever written by Bruce Springsteen or Gillian Welch.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to try my hand at motherhood. I’ll put stars on all my kids’ bedroom doors and refer to them as “the talent.”

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I want to be a truck driver. I’d get on the CB radio and say things like, “Greensleeves, this is the Queen of Sheba. We got a bear in the woods at 6 o’clock. Do you copy?” I love driving and dingy motels and the idea of picking up random hitchhikers and teasing out their life stories. In high school, I used to go to the Irving Big Stop for breakfast so I could check out the rigs parked out front.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’ve been writing stories since I learned to hold a pencil. It chose me and I chose it, and that’s all there is to it.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

My measure for evaluating the merit of a book or film is if I’m still thinking about the story or subject matter a month later. The last great book I read was The Inconvenient Indian by Thomas King. Film-wise, recent favourites are Boyhood and a documentary called the Wolfpack .

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’ve started a new novel. It’s a ghost story set in an old church at the onset of winter. Starting next month, I’ll be home writing full-time in front of the woodstove and scaring myself senseless.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on February 22, 2016 05:31

February 21, 2016

Lake fill (poem)

1.

Schooner, vessel. Unwrapdecades of accumulation: wet clay,

rhyme, diversion.

Long crossed-out: this airless tombof tempered wood. Exhumed,

bare-skin and bone,a glossary, exposed claw-damp

begins to oxidize.

2.

Scalpel-strips

of layers, waterfront. A catalogueddementia: two

centuries of sleep. Padded earththey set for salvage, restitution,

new foundations: railof Grand Trunk.

3.

Repurposed, raised

, what hastens speed: invention.Intact beams are sharpened, shift

to upkeep Historic Fort York.Wood

of equal vintage, timber,

tender. Walks upon, erodes. The faintest tingeof slow.

4.

Erasure: drowning, dry land. Double-masted,fifty foot of sail-set; driven,

run aground. Had weathered

every storm. So purposeful:mid-century, stone-sunk, reshaped

as scaffolding

for Queens Wharf. Setyour body down.

5.

Oh how she scoons,

they would have said.

The lake shrinks slowly, swells.

Published on February 21, 2016 05:31

February 20, 2016

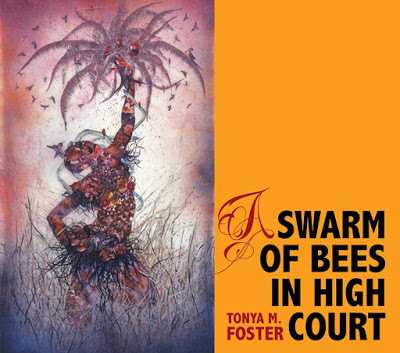

Tonya M. Foster, A Swarm of Bees in High Court

To be—the waterthat bandies a body, thebody of a once

young wo/man ona bayou of sound & words inthe pre/ab/sense of sleep.

To be—a boat asin raft or pontoon. Each word,a boat in which s/he

is, in which s/he issentenced and bandied about.To be about to…

To beabout…

To bebandied about by water,to bebusted and broke,to bebored, grief-bore, work-bore.

to bleed,

to bebackache, bone of nightshifts,to bebarren as salt lick, to bear bellyache and bloat,to benews and less.

To be—tethered between seer and (un)seen.

To see and to beseen?—what it is to live onperennial blocks.

Her voice, no matter how loud or clear, is rendered silence, his do—shadow projected across a page, across a street, an age, acrosstwo bodies in bed. (“AUBADE”)

Harlem, New York poet Tonya M. Foster’s first full-length poetry collection is

A Swarm of Bees in High Court

(Brooklyn NY: Belladonna, 2015), a rhythmic free-style of sharp and precise poems on the immediacty of her space. Her lyrics are dynamic, electric and performative, composed as chants, mantras, sing-song description and sly monologue. Constructed as a book-length poem tied very much to the intricacies of place, A Swarm of Bees in High Court is passionate and tactile, descriptive and vocal; a book very much meant to be heard, and, through her writing, sings off the page. Her poems are infused with lyric, word and soundplay, playing off spoken as much as written language, writing: “be low be lack be ridge and grudge / be longing be sotted be ramble and hold / be come and go; be rim and ram the ball into the basket. / be ram-in-the-bush important / be stung be ache be ring / be stung be ache be ring / be reft and reach over / be attitudes of bee sting[.]” Her poems are declarative (“Grammatical I / ons: shit happens, shit be done / happened, shit be. //// Grammatical “I” / says, “Am.” “Am.” “Let.” “Am I?” “I’ma / tell Mama.” “I am.””), demanding attention and action, calling for critical thinking, and explore an appreciation for the complexities of human interaction and being, all set within the urban setting of Harlem, New York. This is a love song to a neighbourhood and a population that pulls no punches, writing on violence, race, gender and culture; mourning losses and celebrating victories.

Harlem, New York poet Tonya M. Foster’s first full-length poetry collection is

A Swarm of Bees in High Court

(Brooklyn NY: Belladonna, 2015), a rhythmic free-style of sharp and precise poems on the immediacty of her space. Her lyrics are dynamic, electric and performative, composed as chants, mantras, sing-song description and sly monologue. Constructed as a book-length poem tied very much to the intricacies of place, A Swarm of Bees in High Court is passionate and tactile, descriptive and vocal; a book very much meant to be heard, and, through her writing, sings off the page. Her poems are infused with lyric, word and soundplay, playing off spoken as much as written language, writing: “be low be lack be ridge and grudge / be longing be sotted be ramble and hold / be come and go; be rim and ram the ball into the basket. / be ram-in-the-bush important / be stung be ache be ring / be stung be ache be ring / be reft and reach over / be attitudes of bee sting[.]” Her poems are declarative (“Grammatical I / ons: shit happens, shit be done / happened, shit be. //// Grammatical “I” / says, “Am.” “Am.” “Let.” “Am I?” “I’ma / tell Mama.” “I am.””), demanding attention and action, calling for critical thinking, and explore an appreciation for the complexities of human interaction and being, all set within the urban setting of Harlem, New York. This is a love song to a neighbourhood and a population that pulls no punches, writing on violence, race, gender and culture; mourning losses and celebrating victories. Built in thirteen sections—“HARLEM NOCTURN/E/S,” “IN/SOMNIA,” “IN/SOMNILOQUIES” “AUBADE,” “BULLET/IN,” “HIGH COURT,” “B-BALL,” “SWARMS,” “HARLEM NOCTURN/E/S 2,” “TO SHAKE OR BE SHOOK DOWN,” “A GRAMMAR OF WAKING,” “A GRAMMAR OF WAKING: BAREFOOT AND GRASS” and “NOTES: TITULAR LINEAGES,” the title of the fifth section, for example, plays off breaking news and a painful reality of urban life in the United States. Hers is a bold, confident and articulate declaration, and her language is vigorous, pulsing and unyielding, such as the opening of the section “B-BALL,” that pounds and sings:

Bounce-slap goes a ballon a dark court. Hands, knees, andfeet block slam and pass

Steel comes in drum/strings his-her hands might boom/pling; gaze or spine

Bounce-slap goes a ball;drilled-in-eye-dreams till concretewith motion and sound

Steel comes in these forms; blade, beam, molten, to feed, open, will, release

Bounce-slap goes a ball,a hand. In memory, theeye is quicker

Steel come in, like a needle or love, like bodies of sound, of flesh, into

To end the collection, her “NOTES: TITULAR LINEAGES” reads:

From A Swarm of Bees in the Palace of Justiceto A Swarm of Bees in High Court

The vibrant chromatic chaos and the haunting title of Max Ernst’s painting—A Swarm of Bees in the Palace of Justice—were two of the triggering tunes for this poetry. I first encountered the painting in the mid 1990s at The Menil Collection in Houston. For years, a small notebook carried the title and a small off-color reproduction of the work. I found myself turning, over time, to the question of how I might contend with Ernst’s parsing of a visual field.

Several unfinished pieces were written as riffs off of Ernst’s provocation. Some pieces and lines focused on “color,” on relationships and hierarchies between and among hues. Other pieces focused on a sense of fragmentation evoked by the small two-dimensional areas allotted to each color on the broad field of Ernst’s painting.

I had held onto Ernst’s title and the small color copy for years, carrying them with me in my moves from Houston to Jersey City to Harlem, making notes along the varied ways of language, images, moments than seemed somehow related, seemed like green offshoots of Ernst’s multifaceted title. At times, my notes, lines, phrases focused on the swarm, as collective or group or as mass, and, also, swarm as movement.

Bees are communal, plural, public, unindividuated, corporate, en masse. “Bees” triggered images of bees, of course. The bee also becomes s/he, syllable, sound—“b” and to be. I began to understand the problem of how to contend with the myriad impulses provoked by the painting as a problem of form. First, I changed the title. There are no surviving palaces or much talk of palaces in Harlem. There is a basketball court, where one might through practice and chops rule. There is a constant courting on stoops and corners. There is the etiquette of courtship. There is the train to the courthouse. There are the nearby cops who card neighborhood congregants. There is the height of the hills, the height of the apartment buildings, the height of the cameras focused on streets and doorways and the small Saint Nicholas Park. There are myriad highs, highs from rocks, totes, and forties. High-tops hanging from phone lines. There is the high of the noisy and high-flying ghetto birds that flash their brights some early summer evenings. A Swarm of Bees in the Palace of Justice became A Swarm of Bees in High Court.

I began to think about and collect language of the place—the people and things that occupy the place. This is a biography of life in the day of a particular neighborhood. The cameras, bodies, televised portrayals, voices, and doorways of the place demanded a different pronoun for dealing with the multiple as subject and as swarm of actors.

Central to this meditation—“We think, therefore we are t/here, therefore t/here is.”

Published on February 20, 2016 05:31

February 19, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Kristjana Gunnars (1989-1990)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers, as well as information on the upcoming anniversary event, here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Kristjana Gunnars

[photo credit: Cindy Goodman of North Shore News, Vancouver] is a painter and writer, author of several books of poetry, short fiction and anti-fiction. She is Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing and English at the University of Alberta, and now works out of her studio in B.C. Her current work-in-progress is a poetry collection titled “Snake Charmers,” a selection of which just appeared as a chapbook with above/ground press. Her web connection is: kristjanagunnars.com

Kristjana Gunnars

[photo credit: Cindy Goodman of North Shore News, Vancouver] is a painter and writer, author of several books of poetry, short fiction and anti-fiction. She is Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing and English at the University of Alberta, and now works out of her studio in B.C. Her current work-in-progress is a poetry collection titled “Snake Charmers,” a selection of which just appeared as a chapbook with above/ground press. Her web connection is: kristjanagunnars.com

She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1989-1990 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d been publishing books for nearly a decade. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: I was in the middle of my “quintet” of mixed-genre publications with Red Deer Press when I was invited to be w.i.r. at Alberta U. I was at the time writer in residence at the Regina Public Library and this seemed like a logical next step. I missed the academic atmosphere, so was glad to get back to it this way. I was interested in exploring new avenues in writing just then, to be involved in front-line writing theory, and the U was a good environment for that, many interesting colleagues and students there. At the time I was not very interested in the commercial aspect of writing and book publishing, but more the philosophical and theoretical. That’s not to say I didn’t want to sell books etc., all that, but rather if that’s all you’re interested in (numbers and attention) the writing life just dies. It’s dead, and writing becomes a kind of rat race. I’ve always enjoyed reading and researching, so in a way coming to the UofA as writer in residence was a kind of heaven. Good bookstores and libraries and people. In fact, I ended up staying there for the next 14 years, joining the faculty, so the opportunity in the first place was pretty important.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: At the University of Alberta the schedule of meetings with writers was very packed. I met with writing students and students who were not in the writing program, as well as faculty members who wanted comments on their writing. I also had a lot of people from the broader community, from all walks of life. They all had interesting stories to tell. Many were in life-changing situations so the meetings could get intense. I believe, and hope, the people who came to me benefited. Aside from the writing critiquing, I also gave readings and talks, not just at the university but also in many places in the community, around the province. And I continued to do readings of my own around the country, and to attend conferences.

After joining the UofA English Department, I was in charge of the writer in residence program myself for many years. I selected writers from around the country for a residency and negotiated with them to come. Once they were there, I acted as liaison person for them and stayed in touch during their term. I know that every writer has his or her own interests, and found things to do that were unique. In each case, every new writer added something to the program. Some gave extra lectures, visited classes a lot, produced panel discussions, even comedy performances. Most found friends, many lifetime friends, among the community. Some partied more than others, some pursued private interests alongside or were involved in publishing local writers.

What I hoped to achieve as writer in residence myself was pretty basic: to be a valuable resource for the community of writers in Alberta and at the university. You don’t always know the value of what you are saying to writers about their work, but you can hope there is real growth involved and you can try your best, knowing there is no final response to art. There are only suggestions to be made. Art is art; the artist, and writer, needs to figure it out in private, and all the critic can do is offer observations. I don’t think you can actually tell a writer what to do, unless it’s an obvious thing that crops up. And of course you can warn writers they are heading into questionable territory, or making themselves vulnerable to criticism they had not foreseen.

Having seen this from both sides, I’d say to be a writer in residence the most valuable asset is yourself. To be yourself and bring with you the things you excel in. Make your stay as writer in residence memorable for who you are and add what you can of your own to the existing template.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: Aside from meeting wonderful writers and colleagues, I was glad to see some of the manuscripts I worked on with local writers come into publication. Also, gratifyingly, some writers I met then have become important writers in Canadian literature. That has to be the best accomplishment. That year I was seeing the publication of the second book in my series of five cross-genre books with Red Deer Press. This book, Zero Hour , was gratifying to see in print and it was received well. I did a number of readings and such around it. I feel that work, which was the first time I tackled the issue of loss in writing, was rewarding on many levels, not the least of which was that readers were able to share their stories and the idea of loss in general became much bigger. The book was nominated for the GG’s at the time as well, and won an Alberta book award, all of which helped me in my journey. These were personal accomplishments, but for a writer they are important milestones.

This was also the time I began to worry the issue of genre in Canadian literature. I was hoping to enlarge the discussion of genre and open up an acceptance to texts that did not seem to adhere to any genre; that were not novels, not essays, not memoirs, not poetry, per se, but that could be all of these at once. I never liked the sense of being “trapped”, and the idea of genre—meaning if you’re writing a story you should conduct it like a proper story, and if it’s a poem then certain unwritten rules apply, etc.—always did seem like a form of entrapment. I began a study of how I could talk about this within the academic framework, and I continued something I had started back at the University of Manitoba in literary theory. That project has stayed with me since. I am gratified to see that cross-genre books are now frequently published in Canada and well accepted. If I have contributed to that development at all, I would consider it a big accomplishment. Being writer in residence at the U. of A. gave me a chance to focus on and consolidate many of my ideas in this area.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I should correct you a little bit. I am an Alberta writer. I was in Alberta so long, was involved in the Alberta writing scene for many years. I still consider myself an Alberta writer; something that began before I first moved there, through the Markerville Icelandic connection and my work on the translation of Stephan G. Stephansson, and not to mention, my publisher was at Red Deer. But my year as writer in residence was my first year of actually living in Alberta, so at that time I may not have been an Alberta writer as such.

The landscape of Alberta has influenced me, as have the landscapes of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In particular, the farmland and low hills around Markerville became very close to me. I was in particular influenced by Robert Kroetsch, his Alberta works, esp. Badlands and Seed Catalogue . I was also greatly influenced by Rudy Wiebe. At that time they were both a strong part of the literary scene in Alberta and there was a lot going on around them. They provided a kind of cohesion to the literary community at the time, and were very encouraging. That time I also met Myrna Kostash and Aritha Van Herk, both very strong voices and they too held a lot of influence. At the time of my writer residency, I had the sense that a bolt of energy had hit the writing community and there was a lot of excitement about the future. A very good time to move into the scene.

Kristjana Gunnars

[photo credit: Cindy Goodman of North Shore News, Vancouver] is a painter and writer, author of several books of poetry, short fiction and anti-fiction. She is Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing and English at the University of Alberta, and now works out of her studio in B.C. Her current work-in-progress is a poetry collection titled “Snake Charmers,” a selection of which just appeared as a chapbook with above/ground press. Her web connection is: kristjanagunnars.com

Kristjana Gunnars

[photo credit: Cindy Goodman of North Shore News, Vancouver] is a painter and writer, author of several books of poetry, short fiction and anti-fiction. She is Professor Emeritus of Creative Writing and English at the University of Alberta, and now works out of her studio in B.C. Her current work-in-progress is a poetry collection titled “Snake Charmers,” a selection of which just appeared as a chapbook with above/ground press. Her web connection is: kristjanagunnars.comShe was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1989-1990 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d been publishing books for nearly a decade. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: I was in the middle of my “quintet” of mixed-genre publications with Red Deer Press when I was invited to be w.i.r. at Alberta U. I was at the time writer in residence at the Regina Public Library and this seemed like a logical next step. I missed the academic atmosphere, so was glad to get back to it this way. I was interested in exploring new avenues in writing just then, to be involved in front-line writing theory, and the U was a good environment for that, many interesting colleagues and students there. At the time I was not very interested in the commercial aspect of writing and book publishing, but more the philosophical and theoretical. That’s not to say I didn’t want to sell books etc., all that, but rather if that’s all you’re interested in (numbers and attention) the writing life just dies. It’s dead, and writing becomes a kind of rat race. I’ve always enjoyed reading and researching, so in a way coming to the UofA as writer in residence was a kind of heaven. Good bookstores and libraries and people. In fact, I ended up staying there for the next 14 years, joining the faculty, so the opportunity in the first place was pretty important.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: At the University of Alberta the schedule of meetings with writers was very packed. I met with writing students and students who were not in the writing program, as well as faculty members who wanted comments on their writing. I also had a lot of people from the broader community, from all walks of life. They all had interesting stories to tell. Many were in life-changing situations so the meetings could get intense. I believe, and hope, the people who came to me benefited. Aside from the writing critiquing, I also gave readings and talks, not just at the university but also in many places in the community, around the province. And I continued to do readings of my own around the country, and to attend conferences.

After joining the UofA English Department, I was in charge of the writer in residence program myself for many years. I selected writers from around the country for a residency and negotiated with them to come. Once they were there, I acted as liaison person for them and stayed in touch during their term. I know that every writer has his or her own interests, and found things to do that were unique. In each case, every new writer added something to the program. Some gave extra lectures, visited classes a lot, produced panel discussions, even comedy performances. Most found friends, many lifetime friends, among the community. Some partied more than others, some pursued private interests alongside or were involved in publishing local writers.

What I hoped to achieve as writer in residence myself was pretty basic: to be a valuable resource for the community of writers in Alberta and at the university. You don’t always know the value of what you are saying to writers about their work, but you can hope there is real growth involved and you can try your best, knowing there is no final response to art. There are only suggestions to be made. Art is art; the artist, and writer, needs to figure it out in private, and all the critic can do is offer observations. I don’t think you can actually tell a writer what to do, unless it’s an obvious thing that crops up. And of course you can warn writers they are heading into questionable territory, or making themselves vulnerable to criticism they had not foreseen.

Having seen this from both sides, I’d say to be a writer in residence the most valuable asset is yourself. To be yourself and bring with you the things you excel in. Make your stay as writer in residence memorable for who you are and add what you can of your own to the existing template.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: Aside from meeting wonderful writers and colleagues, I was glad to see some of the manuscripts I worked on with local writers come into publication. Also, gratifyingly, some writers I met then have become important writers in Canadian literature. That has to be the best accomplishment. That year I was seeing the publication of the second book in my series of five cross-genre books with Red Deer Press. This book, Zero Hour , was gratifying to see in print and it was received well. I did a number of readings and such around it. I feel that work, which was the first time I tackled the issue of loss in writing, was rewarding on many levels, not the least of which was that readers were able to share their stories and the idea of loss in general became much bigger. The book was nominated for the GG’s at the time as well, and won an Alberta book award, all of which helped me in my journey. These were personal accomplishments, but for a writer they are important milestones.

This was also the time I began to worry the issue of genre in Canadian literature. I was hoping to enlarge the discussion of genre and open up an acceptance to texts that did not seem to adhere to any genre; that were not novels, not essays, not memoirs, not poetry, per se, but that could be all of these at once. I never liked the sense of being “trapped”, and the idea of genre—meaning if you’re writing a story you should conduct it like a proper story, and if it’s a poem then certain unwritten rules apply, etc.—always did seem like a form of entrapment. I began a study of how I could talk about this within the academic framework, and I continued something I had started back at the University of Manitoba in literary theory. That project has stayed with me since. I am gratified to see that cross-genre books are now frequently published in Canada and well accepted. If I have contributed to that development at all, I would consider it a big accomplishment. Being writer in residence at the U. of A. gave me a chance to focus on and consolidate many of my ideas in this area.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I should correct you a little bit. I am an Alberta writer. I was in Alberta so long, was involved in the Alberta writing scene for many years. I still consider myself an Alberta writer; something that began before I first moved there, through the Markerville Icelandic connection and my work on the translation of Stephan G. Stephansson, and not to mention, my publisher was at Red Deer. But my year as writer in residence was my first year of actually living in Alberta, so at that time I may not have been an Alberta writer as such.

The landscape of Alberta has influenced me, as have the landscapes of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In particular, the farmland and low hills around Markerville became very close to me. I was in particular influenced by Robert Kroetsch, his Alberta works, esp. Badlands and Seed Catalogue . I was also greatly influenced by Rudy Wiebe. At that time they were both a strong part of the literary scene in Alberta and there was a lot going on around them. They provided a kind of cohesion to the literary community at the time, and were very encouraging. That time I also met Myrna Kostash and Aritha Van Herk, both very strong voices and they too held a lot of influence. At the time of my writer residency, I had the sense that a bolt of energy had hit the writing community and there was a lot of excitement about the future. A very good time to move into the scene.

Published on February 19, 2016 05:31

February 18, 2016

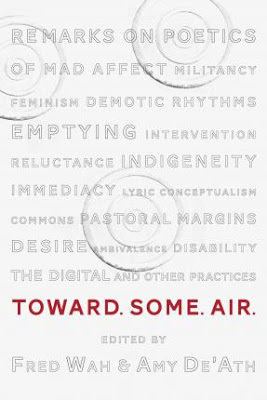

Toward. Some. Air. eds. Fred Wah and Amy De’Ath

The positions articulated in this anthology are vastly different, crossing generational, geographical, and theoretical borders, and in this sense we are aiming to encourage dialogue by proximity but also to suggest a looking-outwards; not so much towards other individual poets but towards other poetics and ways of being in the world. In this spirit some of the pieces included advocate different ways of listening. Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm and Christine Stewart emphasize the importance of listening for a politics of decolonization in the settler-colonial state of Canada; Maria Damon, speaking of her position as a critic, modestly characterizes herself as the “cheer-leader,” the “friend of poets,” the “poetry-enabler”; Sean Bonney and Stephen Collis discuss the difficulties of listening to the cacophony of voices present in a collective, and the dangers of privileging the poet-subject who imagines s/he might speak for, rather than with, the otherwise excluded subject who is wrongly perceived as “voiceless.” For many of the poets in this book, listening is a political practice that moves away from the individuating compulsions of singular authorship and towards modes of collectivity, perhaps to imagine what a collective subjectivity might mean. For all its difference, the work collected here is also testament to a widespread interest in the relation between poetry and social change, or between poetry and revolution, even as the latter may involve an assertion that poetry cannot do the same work as gathering of bodies at a protest or a riot. (Amy De’Ath, “Foreword”)

I’m quite amazed by Toward. Some. Air. (Banff AB: Banff Centre Press, 2015), a remarkable poetics anthology edited by Fred Wah and Amy De’Ath. Subtitled “Remarks on Poetics of Mad Affect | Militancy | Feminism | Demotic Rhythms | Emptying | Intervention | Reluctance | Indigeneity | Immediacy | Lyric Conceptualism | Commons | Pastoral Margins | Desire | Ambivalence | Disability | The Digital | and Other Practices,” the book collections a wide range of creative and critical works by Canadian, American and British poets and critics: Peter Jaeger, Anne Boyer, Andrea Brady, Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm and Rita Wong, Jeff Derksen, Kaia Sand, Justin Katko, Liz Howard, Larissa Lai, Reg Johanson, Michael Davidson, Nicole Markotić, Lisa Robertson, Kirsten Emiko McAllister and Roy Miki, Caroline Bergvall, cris cheek, Fred Moten, José Esteban Muñoz, Steven Ross Smith, Christine Stewart, Keston Sutherland, Eileen Myles, Hoa Nguyen and Dale Smith, Dionne Brand and Nicole Brossard, Nicole Brossard and Fred Wah, Jow Lindsay, Keith Tuma, Amy De’Ath, Catherine Wagner, Rachel Zolf, Peter Manson, Louis Cabri, J.R. Carpenter, Lori Emerson, David Jhave Johnston, Nick Montfort, Stuart Moulthrop, Brian Kim Stefans, Stephanie Strickland, Darren Wershler, Sina Queyras, Daphne Marlatt, Sean Bonney and Stephen Collis, Maria Damon, Juliana Spahr and Amy De’Ath, and CAConrad. What is truly remarkable about the collection is in how it attempts to introduce, engage and even clarify, an incredible amount of contemporary conversations on poetry practice across North America and the UK. While the book doesn’t pretend to be all-inclusive or complete in any way, it does manage to bring together a much larger range of contemporary poetic practices than I’ve seen in any other single volume in quite a long time (if at all).

I’m quite amazed by Toward. Some. Air. (Banff AB: Banff Centre Press, 2015), a remarkable poetics anthology edited by Fred Wah and Amy De’Ath. Subtitled “Remarks on Poetics of Mad Affect | Militancy | Feminism | Demotic Rhythms | Emptying | Intervention | Reluctance | Indigeneity | Immediacy | Lyric Conceptualism | Commons | Pastoral Margins | Desire | Ambivalence | Disability | The Digital | and Other Practices,” the book collections a wide range of creative and critical works by Canadian, American and British poets and critics: Peter Jaeger, Anne Boyer, Andrea Brady, Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm and Rita Wong, Jeff Derksen, Kaia Sand, Justin Katko, Liz Howard, Larissa Lai, Reg Johanson, Michael Davidson, Nicole Markotić, Lisa Robertson, Kirsten Emiko McAllister and Roy Miki, Caroline Bergvall, cris cheek, Fred Moten, José Esteban Muñoz, Steven Ross Smith, Christine Stewart, Keston Sutherland, Eileen Myles, Hoa Nguyen and Dale Smith, Dionne Brand and Nicole Brossard, Nicole Brossard and Fred Wah, Jow Lindsay, Keith Tuma, Amy De’Ath, Catherine Wagner, Rachel Zolf, Peter Manson, Louis Cabri, J.R. Carpenter, Lori Emerson, David Jhave Johnston, Nick Montfort, Stuart Moulthrop, Brian Kim Stefans, Stephanie Strickland, Darren Wershler, Sina Queyras, Daphne Marlatt, Sean Bonney and Stephen Collis, Maria Damon, Juliana Spahr and Amy De’Ath, and CAConrad. What is truly remarkable about the collection is in how it attempts to introduce, engage and even clarify, an incredible amount of contemporary conversations on poetry practice across North America and the UK. While the book doesn’t pretend to be all-inclusive or complete in any way, it does manage to bring together a much larger range of contemporary poetic practices than I’ve seen in any other single volume in quite a long time (if at all). Honestly I don’t really like to write about prose so much because, in a way that seems true for me about prose and not so much about poetry, the practice of prose is both theory and practice. It’s one body. I mean discourse gives poets an opportunity to write prose and I think that is a pleasure in itself but prose writers, and even ones like myself who like to call themselves fiction writers or non-fiction writers and “poet,” too, depending on the mood, I think, would rather just do it and have it contain all its marvels, including thought about itself. There’s nothing about fiction or non-fiction that can’t contain thinking about itself and extrapolating about that. It’s like dropping your pen and noticing the room and then sitting up and keeping going. It’s like getting up to make tea or shitting or something like that. Thinking about the practice and the practice itself are part of the same territory in fiction so of course when you asked me to do this I thought oh fuck but I am working on a book. (Eileen Myles, from “Reluctance”)

An important feature of the anthology is in understanding how much of the conversations explored here (some of which have been building for years), as well as a number of contributors, aren’t often collected for a book such as this, especially one that exists across more than a couple national borders. As well, many of these conversations become required reading in part for their prior absence in the larger sphere, having long existed on the fringes of literary discourse, or simply too new to have been properly explored, whether conversations concerning new media, post-colonial attitudes and Idle No More, disability poetics, archival projects and post-lyric sensibilities, and any number of further conversations involving gender, race, resistance, reconciliation, violence and attention. At three hundred and forty-eight pages, this is a hefty volume, and one that anyone could and should spend a great deal of time working to absorb. What makes Toward. Some. Air.such an important anthology is in the wide range of discourses it contains, all of which have long been existing just under the surface of literary conversation; with increasing volume and intensity, these are the conversations that will be existing in the ways in which we write, read and comprehend ourselves. If you want to know what is happening, in writing and the larger discourse, this is a place to begin. As Larissa Lai writes to open her “An Ontology and Practice for Incomplete Futures”:

If the practice is to be meaningful, it must engage language, body, history, memory, the present, the unconscious, imagination, ethics, and relation in a drive towards the future.

There are also a number of more direct conversations in the collection, including an essay on the work of the late poet Peter Culley by Lisa Robertson (“Listening in Culley’s work is an economy that, while seemingly as at ease with its demotic setting as it is with a profound literariness, subtly undercuts itself with a sonically installed irony.”), the poet and critic Dale Smith interviewing his long-time partner, co-editor and co-publisher, the poet Hoa Nguyen, Keith Tuma on the work of British poet Tom Raworth, and Christine Stewart’s ongoing exploration of Edmonton’s Mill Street Bridge, specifically “Treaty Six”:

the underbridge

The underbridge at Mill Creek is an exposed edge, scarred by the extraction of resources, development, and the displacement of people. Its dynamics and devastations, its sleepers, reveal the Treaty violations and the government’s continued bio-control of Indigenous peoples and their land – all that remains at the heart of Edmonton, and of Canada. There are hundreds of underbridges in this country – colonized spaces, debris fields, wounded, appropriated earth, displaced Indigenous communites. How to heal this wound, how to honour the treaties, the obligations of sharing Indigenous land? How to be here? As a non-Indigenous person embedded and implicated in white settler ideology, who is that I that I am? What forces have formed me, my sense of land entitlement, and this gaze? That I, here, settled and settling, unsettled and unsettling, born in a country that is a collective and purposeful creation of forgetting, oblivescent, obliterating; not a place of limitless potential, but a nation that demands a baseline of deprivation and suffering. There is always someone sleeping under the bridge there is always an Attawapiskat. There is no post-colonial, but there is capitalism, and these are these conditions that constitute Canada: land and resource theft, the enforced dislocation of communitites, genocidal administrative systems, and government-sanctioned amnesia. Under the bridge at Mill Creek, composer Jacquie Leggatt and I listen, gathering rhythms and vibrations that are material and specific to the stream, to the ravine, to the river valley and to the river. Next to the huge cement piers, to the thin trees and the creek, under the bridge, noise envelops us. Wearing Jacquie’s earphones, holding the Sony recorder, we encounter layers of sound, emetings of lives; dog, jogger, stone, water, car, bird, two men (yelling from the bridge deck above). Noise swarms the listening body – from behind, from above, from below. The eyes close; the I shifts and is shaken. In its immediate proximity (surrounded) with the materiality of sound, the body encounters the permeability of its own matter. The ears can’t and won’t block the siren, the car alarm, booming truck, ragged breath, coughing body; each noise enters, moves through. The underbridge: kâhasinîskâk, place of stones, and stories, buffalo trail, a dense growth of trees and brush, remnants of a shanty town, holes from the coal mines, cow bones from the abattoir, inhabited coyote den, defunct railway: the resonant matter of this place.

Another highlight in a series of highlights is the conversation between British poet Sean Bonney and Vancouver poet Stephen Collis, “We Are An Other: Poetry, Commons, Subjectivity,” that includes:

Sean Bonney:I’ve always been interested in subjectivity, at first because certainly in the London avant-poetry scene, when I first showed up, lyric expression was a real no-no – the whole scene seemed to have very rigid rules. And anyway, dogmas against the lyric subject in poetry – from Olson on – always assume that we’re talking about a middle-class, usually male, usually white subject, as if the only people who could be interested in the “avant-garde” would be white posh men. It is easy to deny subjectivity when yours is the dominant. There’s no need to assert it because it permeates the entire atmosphere of social reality.

Published on February 18, 2016 05:31

February 17, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lauren Camp

Lauren Camp is the author of three books—

This Business of Wisdom

(2010);

The Dailiness

(2013), winner of the National Federation of Press Women Poetry Prize; and One Hundred Hungers (Tupelo Press, 2016), winner of the Dorset Prize. Her poems appear in Poetry International, Slice, The Seattle Review, World Literature Today, Beloit Poetry Journal and elsewhere. Other literary honors include the Margaret Randall Poetry Prize, an Anna Davidson Rosenberg Award, and a Black Earth Institute Fellowship. www.laurencamp.com.

Lauren Camp is the author of three books—

This Business of Wisdom

(2010);

The Dailiness

(2013), winner of the National Federation of Press Women Poetry Prize; and One Hundred Hungers (Tupelo Press, 2016), winner of the Dorset Prize. Her poems appear in Poetry International, Slice, The Seattle Review, World Literature Today, Beloit Poetry Journal and elsewhere. Other literary honors include the Margaret Randall Poetry Prize, an Anna Davidson Rosenberg Award, and a Black Earth Institute Fellowship. www.laurencamp.com.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, This Business of Wisdom, gave me credibility — for myself. I was settled into the life and career of a visual artist for a good decade or more before letting poetry co-opt my hands and mind, so having that first book gave me confidence to stay on my new path.

In my second book, The Dailiness, I was still working with some of the same themes of the first—the desert and drought, family issues, loss and jazz—but I was also working through a time in our culture that was more fraught. This shows up in the poems. Both of these books are collections of poems I wrote over the years. I drew them together into books when I thought they began speaking to each other.

Meanwhile, I’d been creating poems for One Hundred Hungers (Tupelo Press, 2016). This third book focuses on a particular place and time: Baghdad, Iraq in the late 1930’s and through the 1940’s. The book is definitely as personal, but more myth-like than the other books.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I found my way to poetry through visual art. I had been building a career as an artist and showing my work around the country and world. When the pieces went on display, venues often requested short “blurbs” about the work. People began to ask if I had written the poetry on exhibit in the room. Pretty much from then on, I realized I could “see” words as art, too. I’ve never stopped writing poetry since.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I only start a poem when I have something to capture or pick apart, so in that way, it doesn’t take long. A first draft rarely looks—or even sounds—like the final poem. I find tremendous joy in moving words around, reducing a poem, reframing it, ruining it, and building it up again. Perhaps it was all those years as an artist, shaping and coloring…

I think temporally when I’m at the mechanic or hoping for enough layover minutes to catch a plane, but I don’t think in terms of time when I’m writing or revising. My writing seems to come out of my life so suddenly that I hardly realize how far along I am in a project until I’m invested, and want to see it through—despite the fact that “through” may still be years away.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

At the beginning, I am working on a thought, an image, a response to an artwork, a chord, a mood. If and when that happens repeatedly with one subject, I begin looking at the possibility of “a book.” I don’t think in terms of books from the start, but lately, I seem to be able to focus on sequences, which makes the book arrangement a bit easier.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I definitely enjoy doing readings and meeting the people who are likely to be readers of my work. In graduate school, one of my majors was oral interpretation of literature. I’ve also had about 15 years of radio broadcasting experience, and I love microphones. But I don’t “try out” drafts on an audience. I only read work I’m convinced is finished.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’d rather leave it to the reviewers and readers to tell me what I’ve answered for them. Making visual art, I focused on the process of creating. Viewers added their own interpretations based on their life paths and perspectives. I loved the surprise of this, and so, I am happy to let it carry over into the poems.

Of course, I am working to unearth something each time I write. I always want to unravel a sentence to its greatest lament or its widest flight, but sometimes, I intend to discover something about self, community, land. Other times, I simply want to preserve something, whether it’s marvelous or awful.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Maybe James Baldwin put it best: “Artists are here to disturb the peace.” That could mean sharing a wound (physical, emotional, communal) or a hope. It might mean making sure we, as humans, focus on some more meaningful things (land, society, inner health, the future, the past) rather than monetary gain, power and prestige all the time.

Or it might mean having the skill and determination to take a thought and flip it on its side in such a way that readers have to listen closer, to truly attend, instead of the quick-quick-hurry-move on action of our current society.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Depends. I teach creative writing workshops to older adults. One of my offerings is a revision workshop, and I school participants in letting their egos move to the outside of the room for a while. But do I do this myself…? Well, I’m very open to good suggestions. I don’t always recognize them right away, but it doesn’t take long for me to at least try something out. A chance to rearrange? I’m usually all for it. Besides, there’s always the undo key.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Oh, this changes steadily, so I’m uncomfortable giving one person credit for keeping me afloat. Lately, I’ve had to call on Barbara Kingsolver’s “I can do hard things,” a statement she made in an interview.

My memory for quotes (and jokes and names) is truly atrocious, but I read enough that I’m always sailing away on beautiful lines and images for a little while—before turning to the next book, next essay, next poem.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to multi-media performance to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

I can move between poetry and performance because they seem like two sides of the same coin. Though I tried desperately, I couldn’t move between poetry and visual art at all. I had to choose one, or let the one most demanding one choose me.

Right now, poetry has all my attention.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My opportunities to write or revise are so hit or miss that the word “routine” is laughable. I am devoted to both, and scramble to find time. Sometimes, I’ll put slender words on tiny scraps of paper, the backs of grocery lists, an appointment card, my palm. I run my own business, so I’m always busy with the correspondence and details that come along with that.

In the best of all possible worlds, I would have time to read AND write every single day. I have it pretty good, but I almost never get those two things to fall neatly into a day.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books. The forest. The gym.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Melting candles; foaming, boiled almonds; green beans and lamb stew. These are from my grandparents’ home, where we went every few weeks to be with the extended family.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Jazz and contemporary visual art are major players in my inspiration. I’ve been very involved in both, the former as an appreciator and disc jockey, the latter as a maker. I like taking them apart and putting them together in this other medium: words, lines, space.

Nature, too, or more accurately terrain, topography and weather conditions, factor into my writing. I live in the high desert. I didn’t grow up here, and it fascinates me. I write to collect it all to me, again and again.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I read voraciously, these days most often poetry. It is the main component of my literary diet. I include three contemporary poems each week on “Audio Saucepan,” my radio show, and so I am ever in search of poems I most want to share.

It’s impossible to call out poets without leaving behind more true favorites. The poetry ground I stand on includes the marks of peers, strangers, people from the generation or two before me, ancients. I’d even include poems I don’t much care for. They all remind me what I want, what I haven’t yet done, and maybe even what or how I hope to never write.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Present my poetry in other countries.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Raptor rescue and rehabilitation. Chocolatier. Honestly (and I say this somewhat saddened by my answer), there isn’t anything else that truly wows me. I “try on” occupations every time I meet someone who does something I can’t fathom. Physical therapist? Nah. Social scientist. Nope.

Though I complain about my ever-tightening schedule, and how much I cram into it, I really do love what I do, or have done, or might do very soon with it.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Art made me write poetry. Being a curious, happy loner of a kid kept me reading and writing and creating.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read Anthony Shadid’s House of Stone recently. It’s a beautiful story about rebuilding an ancestral home in the Middle East.

I’m mostly a fan of documentaries, which give me a chance to get around the world. I loved the humanity in the Clark Terry film Keep On Keeping On, and the structure and tension of Locke .

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m juggling a few manuscripts. I return to them every few months and do an overhaul, pulling poems out, sliding new things in. I’m just about done with a collection of poems about arts patroness Mabel Dodge Luhan and her presence in Taos, New Mexico. I have another sequence of poems about raptors, and a separate grouping that focuses on the ocean and the power and disappearance of memory. I’m most interested in colliding unusual subjects, so I tend to assemble half a collection at a time… and then wait for its other parts to show up.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on February 17, 2016 05:31

February 16, 2016

On Writing : an occasional series

We're nearly three years and more than eighty essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.”

We're nearly three years and more than eighty essays into the occasional series of "On Writing" essays I've been curating over at the ottawa poetry newsletter blog. I've included an updated list, below, of those pieces posted so far, and the list is becoming quite substantive. Way (way) back in April, 2012, I discovered (thanks to Sarah Mangold) the website for the NPM Daily, and absolutely loved the short essays presented on a variety of subjects surrounding the nebulous idea of “on writing.”Forthcoming: new essays by Jani Krulc, Ken Norris, Lillian Necakov, Alice Zorn, Julie Morrissy, A.J. Levin, Ashley-Elisabeth Best, lars palm, Valerie Coulton and Claudia Coutu Radmore.

On Writing #85 : Steven Artelle : On Writing ; On Writing #84 : Chris Eaton : On Writing ; On Writing #83 : Kaie Kellough : Ceremony ; On Writing #82 : Jacqueline Valencia : On Writing ; On Writing #81 : Kevin Killian : Writing the Anthropocene ; On Writing #80 : Mike Spry : On Writing ; On Writing #79 : Dina Del Bucchia : OMG. Watch TV! ; On Writing #78 : Michelle Berry : On Writing ; On Writing #77 : Eric Schmaltz : Writing as an Intimacy with Machines ; On Writing #76 : Barbara Tomash : Dear PRE- ; On Writing #75 : Eileen R. Tabios : NO LONGER CASUAL ; On Writing #74 : Sheryda Warrener : Make It New ; On Writing #73 : Pam Brown : Writing ; On Writing #72 : Renee Rodin : The Nub ; On Writing #71 : Rebecca Rosenblum : Ways to Help a Fellow Writer with His/Her Work ; On Writing #70 : Susannah M. Smith : On Writing ; On Writing #69 : Natalie Simpson : On Writing ; On Writing #68 : Jennifer Kronovet : Fighting and Writing ; On Writing #67 : George Stanley : Writing Old Age ; On Writing #66 : George Fetherling : On Writing ; On Writing #65 : Gail Scott : THE ATTACK OF DIFFICULT PROSE ; On Writing #64 : Laisha Rosnau : The Long Game ; On Writing #63 : Arjun Basu : Write ; On Writing #62 : Angie Abdou : The Writer & The Bottle ; On Writing #61 : Carolyn Marie Souaid : Lawyers, Liars & Writers ; On Writing #60 : Priscila Uppal : On Creative Health ; On Writing #59 : Sky Gilbert : Yes, They Live ; On Writing #58 : Peter Richardson : Cellar Posting ; On Writing #57 : Catherine Owen : "Bright realms of promise": ON THE POETIC ; On Writing #56 : Sarah Burgoyne : a series of permissions-givings ; On Writing #55 : Anne Fleming : Funny ; On Writing #54 : Julie Joosten : On Haptic Pleasures: an Avalanche, the Internet, and Handwriting ; On Writing #53 : David Dowker : Micropoetics, or the Decoherence of Connectionism ; On Writing #52 : Renée Sarojini Saklikar : No language exists on the outside. Finders must venture inside. ; On Writing #51 : Ian Roy : On Writing, Slowly ; On Writing #50 : Rob Budde : On Writing ; On Writing #49 : Monica Kidd : On writing and saving lives ; On Writing #48 : Robert Swereda : Why Bother? ; On Writing #47 : Missy Marston : Children vs Writing: CAGE MATCH! ; On Writing #46 : Carla Barkman : Tastes Like Chicken ; On Writing #45 : Asher Ghaffar : The Pen: ; On Writing #44 : Emily Ursuliak : Writing on Transit ; On Writing #43 : Adam Sol : How I Became a Writer ; On Writing #42 : Jason Christie : To Paraphrase ; On Writing #41 : Gary Barwin : ON WRITING ; On Writing #40 : j/j hastain : Infinite Chakras: a Trans-Temporal Mini-Memoir ; On Writing #39 : Peter Norman : Red Pen of Fury! ; On Writing #38 : Rupert Loydell : Intricately Entangled ; On Writing #37 : M.A.C. Farrant : Eternity Delayed ; On Writing #36 : Gil McElroy : Building a Background ; On Writing #35 : Charmaine Cadeau : Stupid funny. ; On Writing #34 : Beth Follett : Born of That Nothing ; On Writing #33 : Marthe Reed : Drawing Louisiana ; On Writing #32 : Chris Turnbull : Half flings, stridence and visual timber ; On Writing #31 : Kate Schapira : On Writing (Sentences) ; On Writing #30 : Michael Bryson : On Writing ; On Writing #29 : Sara Heinonen : On Writing ; On Writing #28 : Stan Rogal : Writers' Anonymous ; On Writing #27 : Lola Lemire Tostevin : What's in a name? ; On Writing #26 : Kevin Spenst : On Writing ; On Writing #25 : Kate Cayley : An Effort of Attention ; On Writing #24 : Gregory Betts : On Writing ; On Writing #23 : Hailey Higdon : Hiding Places ; On Writing #22 : Matthew Firth : How I write ; On Writing #21 : Nichole McGill : Daring to write again ; On Writing #20 : Rob Thomas : Hey, Short Stuff!: On Writing Kids ; On Writing #19 : Anik See : On Writing ; On Writing #18 : Eric Folsom : On Writing ; On Writing #17 : Edward Smallfield : poetics as space ; On Writing #16 : Sonia Saikaley : Writing Before Dawn to Answer a Curious Calling ; On Writing #15 : Roland Prevost : Ink / Here ; On Writing #14 : Aaron Tucker : On Writing ; On Writing #13 : Sean Johnston : On Writing ; On Writing #12 : Ken Sparling : From some notes for a writing workshop ; On Writing #11 : Abby Paige : On the Invention of Language ; On Writing #10 : Adam Thomlison : On writing less ; On Writing #9 : Christian McPherson : On Writing ; On Writing #8 : Colin Morton : On Writing ; On Writing #7 : Pearl Pirie : Use of Writing ; On Writing #6 : Faizel Deen : Summer, Ottawa. 2013. ; On Writing #5 : Michael Dennis : Who knew? ; On Writing #4 : Michael Blouin : On Process ; On Writing #3 : rob mclennan : On writing (and not writing) ; On Writing #2 : Amanda Earl : Community ; On Writing #1 : Anita Dolman : A little less inspiration, please (Or, What ever happened to patrons, anyway?)

Published on February 16, 2016 05:31

February 15, 2016

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Michael Boughn on shuffaloff

Michael Boughn worked in the Teamsters for nearly 10 years before earning a PhD in 1986 after studying with poets John Clarke and Robert Creeley. He is the author of ten books of poetry, including 22 Skidoo / SubTractions , Great Canadian Poems for the Aged Vol. 1 Illus. Ed ., and City Book 1 – Singular Assumptions . Cosmographia – a post-Lucretian faux micro-epic was short listed for the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2011, prompting a reviewer in the Globe and Mail to describe him as “an obscure veteran poet with a history of being overlooked.” He has also published essays on film, writing, architecture, and music, and, with Victor Coleman, edited Robert Duncan’s The H.D. Book. City – Books 1-3 is forthcoming from Spyuten Dyuvil Press (NYC) in 2016.

rob, That's a whole lot of questions. Maybe if I run a brief history by you, I will hit most them. I started

shuffaloff

in the late 80s when my father died. I received some insurance money and decided to use some of it to make books. I had been interested in the work of small presses for a long time. I guess it started when I stumbled into Robin Blaser's class on Charles Olson at Simon Fraser University in 1968, two years after I immigrated to Canada. He gave me some White Rabbit Press editions of Jack Spicer including Language and A Book of Magazine Verse. They are gorgeous books, exemplary of the best kind of work that came out of the small press movement in the 60s. Through Robin I got involved with the writers around Iron magazine, another small press creation. Years later, working on my PhD at SUNY Buffalo, I got a job in the Poetry/Rare Book room where I spent a lot of time with small press publications doing preservation and cataloging. As a bibliographer (I did a descriptive bibliography of H.D.) I got quite intimate with the physical construction of books.

rob, That's a whole lot of questions. Maybe if I run a brief history by you, I will hit most them. I started

shuffaloff

in the late 80s when my father died. I received some insurance money and decided to use some of it to make books. I had been interested in the work of small presses for a long time. I guess it started when I stumbled into Robin Blaser's class on Charles Olson at Simon Fraser University in 1968, two years after I immigrated to Canada. He gave me some White Rabbit Press editions of Jack Spicer including Language and A Book of Magazine Verse. They are gorgeous books, exemplary of the best kind of work that came out of the small press movement in the 60s. Through Robin I got involved with the writers around Iron magazine, another small press creation. Years later, working on my PhD at SUNY Buffalo, I got a job in the Poetry/Rare Book room where I spent a lot of time with small press publications doing preservation and cataloging. As a bibliographer (I did a descriptive bibliography of H.D.) I got quite intimate with the physical construction of books.I knew I wanted to do something for the community of writers in Buffalo with the insurance money. I was connected to multiple writers – Buffalo has always had a thriving community of writers -- and decided to do a series called Local Habitations. It was ten books and included Robert Creeley, Jack Clarke, Norma Kassirer, Lisa Jarnot, Sherry Robbins, Jorge Guitart, Elizabeth Willis, Randy Prus, Bruce Holsapple, David Tirrell, and myself. It was a snapshot of writing in Buffalo at a specific moment. I tried the commercial route – distributors and financial books and invoices and shipping – and pretty quickly came to the conclusion that the books I published were not really marketable in a way that would ever earn money and all the rigmarole involved with trying to do that just wasted valuable time . Plus, I hated all that part of it. At the same time, I laser printed a little series of chap books called “Four Folds” – they had four sheets of folded paper – and gave them away, and that was pure joy.

shuffaloff

was always transitory, in motion. There was the shuffle off to Buffalo allusion, but the secret reference was Shakespeare's shuffle off this mortal coil. That was Jack Clarke. After Local Habitations, with my resources depleted, and uninterested in books as a business, I didn't do much for a while. With Cass Clarke's help, I edited, designed and published Jack Clarke's marvellous, posthumous epic, In the Analogy. But that was about it for a number of years. By ’93, I had shuffled off back to Canada and eventually Toronto where I got together with Victor Coleman, surely one of the most important figures in the history of Canadian small press publishing.

shuffaloff

was always transitory, in motion. There was the shuffle off to Buffalo allusion, but the secret reference was Shakespeare's shuffle off this mortal coil. That was Jack Clarke. After Local Habitations, with my resources depleted, and uninterested in books as a business, I didn't do much for a while. With Cass Clarke's help, I edited, designed and published Jack Clarke's marvellous, posthumous epic, In the Analogy. But that was about it for a number of years. By ’93, I had shuffled off back to Canada and eventually Toronto where I got together with Victor Coleman, surely one of the most important figures in the history of Canadian small press publishing. Around that time, I wrote a little serial poem called "Off in Wittgenstein's kitchen" and I wanted to show it to some people. Recalling the pleasure of the Four-Folds, instead of just sending a sheaf of paper, I decided to make a little book and send that. It was a pretty little thing, square, about 4" by 4". I think I made 10 of them and mailed them out to people who received it within a week of its composition. I really liked that. This was a way of keeping the poetry as news, rather than some old shit you wrote two or three years ago, which is what most books are. Charles Olson said that poetry is news that stays news, and in order to be true to that, The Institute of Further Studies would print his poems on postcards and mail them outso that people could read them within a week or two of having been written. I was energized by that.

Around that time, I wrote a little serial poem called "Off in Wittgenstein's kitchen" and I wanted to show it to some people. Recalling the pleasure of the Four-Folds, instead of just sending a sheaf of paper, I decided to make a little book and send that. It was a pretty little thing, square, about 4" by 4". I think I made 10 of them and mailed them out to people who received it within a week of its composition. I really liked that. This was a way of keeping the poetry as news, rather than some old shit you wrote two or three years ago, which is what most books are. Charles Olson said that poetry is news that stays news, and in order to be true to that, The Institute of Further Studies would print his poems on postcards and mail them outso that people could read them within a week or two of having been written. I was energized by that.  I am not interested in discourses about "self-publishing." They reflect the reactionary ideology of the Literary Market as managed by the Literature Administration. The Administration reinforces its reactionary authority by guaranteeing the “Literary Excellence” of work selected for publication by “impartial” judges, panels, and committees, none of which are really impartial and whose real job is to uphold the agency of the Machine. I like to think my work is outside that economy. I do not have a career in poetry, don't want one, and don’t want the Administration's little pats on the head and prizes for being a predictable but excellent writer. There are a few things I want to do with words and I know the readers who are interested in them. So I did that with 22 Skidoo and some individual poems from Sub-tractions, like "Ongoing operations to eliminate all pockets of resistance minus one."

I am not interested in discourses about "self-publishing." They reflect the reactionary ideology of the Literary Market as managed by the Literature Administration. The Administration reinforces its reactionary authority by guaranteeing the “Literary Excellence” of work selected for publication by “impartial” judges, panels, and committees, none of which are really impartial and whose real job is to uphold the agency of the Machine. I like to think my work is outside that economy. I do not have a career in poetry, don't want one, and don’t want the Administration's little pats on the head and prizes for being a predictable but excellent writer. There are a few things I want to do with words and I know the readers who are interested in them. So I did that with 22 Skidoo and some individual poems from Sub-tractions, like "Ongoing operations to eliminate all pockets of resistance minus one." When I started writing Cosmographia, a post-Lucretian faux micro-epic, I knew it would be years before the whole book saw print (if ever), so as each book was finished (there are 12 in good epic tradition) I would make 10-20 little hand sewn books on my laser printer using special papers that I picked up in paper stores. They were quite lovely little things, and I would send them out to people who read my work. I'm pretty sure I know most of those people and I have no illusions about them ever becoming a crowd. I never considered the little books to be "publications" which is just another name for Commercial Poetry Product. The value of poetry is elsewhere. Poetry is one of the last forms of art that continues to resist commodification, notwithstanding the efforts of the Creative Writing Machine and the Avant-garde Machine to overcome that resistance and turn it into a saleable product to be used in negotiating academic positions or winning prizes.

When I started writing Cosmographia, a post-Lucretian faux micro-epic, I knew it would be years before the whole book saw print (if ever), so as each book was finished (there are 12 in good epic tradition) I would make 10-20 little hand sewn books on my laser printer using special papers that I picked up in paper stores. They were quite lovely little things, and I would send them out to people who read my work. I'm pretty sure I know most of those people and I have no illusions about them ever becoming a crowd. I never considered the little books to be "publications" which is just another name for Commercial Poetry Product. The value of poetry is elsewhere. Poetry is one of the last forms of art that continues to resist commodification, notwithstanding the efforts of the Creative Writing Machine and the Avant-garde Machine to overcome that resistance and turn it into a saleable product to be used in negotiating academic positions or winning prizes. So, when Victor came to me with the proposal to do a

shuffaloff