Sudipto Das's Blog, page 4

October 20, 2019

Art is The New Science

I studied in a missionary school run by the Ramakrishna Mission – a residential one, in the barren and backward hinterlands of Bengal, quite far away, in the 80s standards, from my home in Calcutta. As expected, we were always under the tight noose of the monks. More than the discipline, what appeared quite intolerable to many was the fact that arts, sports, athletics, music, elocution, dramatics, creative writing, reading non-academic books in library, meditation and even a course on Indian culture were compulsory, apart from of course the normal academics. I would hate the sports and the athletics but looked forward to the music classes. Given my oratory skills I felt ashamed of myself and looked at my friends, who spoke so well in the debates and elocutions, with awe. Indian culture was something that was hated by all. Dramatics was fun. The library class soon became a pursuit for evading the librarian and procuring books deemed inappropriate at our age. Overtime, we all got tired of coming up with newer excuses to dodge the classes we hated and I started landing up on time for the morning athletics and someone we all felt shouldn’t ever sing, just to make sure that the birds didn’t get frightened in a serene afternoon, started attending the music classes regularly, much to our horror.

Few years later, when I was doing my engineering, again at a place quite disconnected from the rest of the world, in an institute established on the lines of Shantiniketan, the word university founded by the universal educationist, philosopher and poet laurel Rabindranath Tagore, upholding the tradition of the Indian style of all-round education, most of us had the same predicament. The English and Economics classes were the most hated and very few people participated in the socio cultural activities, which were no longer compulsory. Not many of us developed much appreciation for liberal arts, or got into the habit of reading non-academic books. The logic was very simple – we had chosen engineering only because we either hated arts or were not good at it.

A quarter century later, when I look around and try to figure out which of my friends have really “excelled”, I do recall what we would be reminded every day in school – that Vivekananda wanted education to be all-round and that education is the manifestation of the perfection already in us, and so on. It was indeed true that the ones who were very active in socio cultural activities or sports or had a very good hold on language or had multiple hobbies have actually “excelled” better than the ones who were only into academics. The ace swimmer of our hostel during engineering leads a bank in Singapore. The best elocutionist in our school, who would always get the highest scores in English and Hindi, has been into a series of very successful startups in the Bay Area. The one who still amazes me with the number of books he keeps on reading regularly is an accomplished fashion designer and heads the apparel division of a very famous brand in India. I can go on and on. I’m sure they would all feel indebted to the monks of our school and the founders of the Indian Institute of Technology for imbibing in them, though forcibly at times, the habit of reading books and taking interest in multiple things, especially various forms of liberal arts and sports.

And this is not for no reason.

Michael Simmons, an award-winning social entrepreneur and bestselling author, in a well-researched article, People Who Have “Too Many Interests” Are More Likely To Be Successful According To Research, sums it up very well in the title. Citing various examples and researches he harps on the importance of the same three things our monks had imbibed in us – (1) continuous learning through reading books, (2) being a polymath with interests in multiple things and (3) appreciating various forms of art. He points out, Barack Obama read an hour a day while in office, Warren Buffett invested 80% of his time in reading and thinking throughout his career, Bill Gates read a book a week and took a yearly two-week reading vacation throughout his entire career.

Warren Buffett has pinpointed the key to his success this way: Read 500 pages every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest.

Larry Page has been known to spend time talking in depth with everyone from Google janitors to nuclear fusion scientists, always on the lookout for what he can learn from them.

Benjamin Franklin said, “An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

Gandhi said, “Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.”

Not learning at least five hours per week (the five-hour rule) is the smoking of the 21st century, Simmons infers. He cites from the book, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, by Charles Murray, most widely known as the co-author of The Bell Curve. The study of the most significant scientists in all of history uncover that 15 of the 20 – the likes of Newton, Galileo, Aristotle, Kepler, Descartes, Huygens, Laplace, Faraday, Pasteur, Ptolemy, Hooke, Leibniz, Euler, Darwin, Maxwell, etc. — were all polymaths.

Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffett, Larry Page, and Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Feynman, Ben Franklin, Thomas Edison, Leonardo Da Vinci, Marie Curie – are/were all polymaths.

The father of Modern Indian Science, Jagadish Chandra Bose, was perhaps one of the most illustrious polymaths in the recent times. An acclaimed physicist – he was the first person in the world to have successfully demonstrated the transmission and reception of electromagnetic waves, thus making him the inventor of radio/wireless communication – his interests soon turned away from electromagnetic waves to response phenomena in plants; this included studies of the effects of electromagnetic radiation on plants, a topical field today. He was also an archaeologist and one of the earliest writers of science fiction in India, apart from being the founder of the Bose Institute, one of the oldest multi-disciplinary research institutes of India.

Very recently, one of the recipients of 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics, Abhijit Banerjee, is also a great chef, who could very well go ahead and win the Australian Master Chef, humors his brother.

10+ academic studies find a correlation between the number of interests/competencies someone develops and their creative impact.

Simmons gives few advantages of being a Polymath.

Advantage 1: Creating an atypical combination of two or more skills you’re merely competent in can lead to a world-class skill set.

Advantage 2: Most creative breakthroughs come via atypical combinations of skills. The paper, Atypical Combinations and Scientific Impacthas found that an analysis of 17.9 million papers spanning all scientific fields suggests: The highest-impact science is primarily grounded in exceptionally conventional combinations of prior work. “There’s a very longstanding idea that the creation of a new thing is about putting existing things together in a new way,” says Jones, an associate professor of management and strategy and the faculty director of the Kellogg Innovation and Entrepreneurship Initiative. “That is, combinations are the key material of creative insight.” Even Isaac Newton famously proclaimed, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Most of the newer areas of research are actually multi-disciplinary in nature. A welfare project like autonomous response to queries by Indian farmers in their language of choice would involve in-depth skills in diverse fields like comparative linguistics (to identify the correct dialect and language), psychology (to understand the mental state of the speaker and respond sensitively), history (to appreciate the historical and cultural nuances), apart from advanced AI/ML enabled technologies for speech recognition, translation and finding the right answers to the questions asked. Real-time remote surgery is one of the many talked about usages of 5G – anyone could guess the number of disciplines involved in making this happen.

Advantage 3: It future-proofs your career. “It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive,” said Darwin, “but those who can best manage change.”

Advantage 4: It sets you up to solve more complex problems.

The HBR article, Research: CEOs with Diverse Networks Create Higher Firm Value, points out that diverse network would give CEOs access to diverse sets of knowledge, which can lead to novel ideas and willingness to tackle innovative projects. Heterogeneous social ties would increase a CEO’s ability to obtain a network of foreign contacts and identify good business opportunities. What this finding implies is that, apart from the conventional ways of learning – through books, schools, teachers, etc. – it’s also important to learn through diverse social interaction, mingling with all types of people around, traveling to new places and understanding new cultures and peoples. It’s no wonder that both Narendranath Dutta and Mohandas Gandhi had undertaken a painstaking journey across India to understand the peoples and cultures of their country, before they became Swami Vivekananda and Mahatma Gandhi, two of the most successful leaders of modern India from two different walks of life. In Sanskrit, there’s a name to the seeker of wisdom through traveling and interacting with people – parivrajak.

Now that we understand the importance of multiple interests and diverse knowledge, let’s see which all domains seem to be more relevant and useful in the coming days.

In another HBR article, Liberal Arts in the Data Age, the author says, “From Silicon Valley to the Pentagon, people are beginning to realize that to effectively tackle today’s biggest social and technological challenges, we need to think critically about their human context—something humanities graduates happen to be well trained to do. Call it the revenge of the film, history, and philosophy nerds.”

The author cites three books in this context. Scott Hartley, the author of the first one, The Fuzzy And The Techie, first heard the terms fuzzy and techie while studying political science at Stanford University. If you majored in the humanities or social sciences, you were a fuzzy. If you majored in the computer sciences, you were a techie. But in his brilliantly contrarian book, Hartley reveals the counterintuitive reality of business today: it’s actually the fuzzies – not the techies – who are playing the key roles in developing the most creative and successful new business ideas. They are often the ones who understand the life issues that need solving and offer the best approaches for doing so. It is they who are bringing context to code, and ethics to algorithms. They also bring the management and communication skills, the soft skills that are so vital to spurring growth. If we want to prepare students to solve large-scale human problems, Hartley argues, we must push them to widen, not narrow, their education and interests. He ticks off a long list of successful tech leaders who hold degrees in the humanities: Jack Ma, Alibaba – English, Susan Wojcicki, YouTube – History and Literature, Brian Chesky, Airbnb – Fine Arts. Steve Jobs is of course the most prolific one in this long list.

In the second book, Cents and Sensibility: What Economics Can Learn from the Humanities, the authors Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro, professors of the Humanities and Economics, respectively, at the Northwestern University, argue that when economic models fall short, they do so for want of human understanding. The solution is literature, they say. They suggest that economists could gain wisdom from reading great novelists, who have a deeper insight into people than social scientists do. Nothing could be more true than this. Quite a bit of Gandhi’s understanding of humanity and the crystallization of his concepts of nonviolence is influenced by Tolstoy, especially his novel War and Peace. Same holds true for many of Tagore’s novels, especially Gora, in the context of people’s understanding and reaction to Gandhi’s Satyagraha. Novelists are among the best observers and teachers about peoples and their cultures.

Finally, in the last book Sensemaking: The Power of the Humanities in the Age of the Algorithm, the author Christian Madsbjerg argues that unless companies take pains to understand the human beings represented in their data sets, they risk losing touch with the markets they’re serving. He says the deep cultural knowledge businesses need comes not from numbers-driven market research but from a humanities-driven study of texts, languages, and people.

In this context it’s quite relevant that the Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer, who studied computer science, philosophy and psychology, but said a course in theatre taught her a lesson she uses daily in technology product development. On the stage, she said, the playwright has to explicitly explain what’s happening, or leave it to the audience to understand implicitly.

The HBR article, The Best Leaders See Things That Others Don’t. Art Can Help, says the real act of discovery consists not in finding new lands but in seeing with new eyes. Art, it turns out, can be an important tool to change how leaders see their work.

“Study the science of art,” said Leonardo Da Vinci, one of the greatest medieval polymaths. “Study the art of science. Develop your senses — especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

“The greatest scientists are artists as well,” said Einstein, who was also a violinist and would carry his violin everywhere he went.

Steve Jobs perhaps made the most important concluding remarks about the importance of art. “Technology alone is not enough,” he said. “It’s technology married with the liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields the results that makes our hearts sing.”

It might not be an overstatement that what we’ve been talking about is actually a retelling of what Vivekananda had said more than a hundred years back: What we want is to see the man who is harmoniously developed great in heart, great in mind, [great in deed]… We want the man whose heart feels intensely the miseries and sorrows of the world… And [we want] the man who not only can feel but can find the meaning of things, who delves deeply into the heart of nature and understanding. [We want] the man who will not even stop there, [but] who wants to work out [the feeling and meaning by actual deeds]. Such a combination of head, heart, and hand is what we want.

A great combination of “head, heart, and hand” is the essence of an all-round education, that makes a great leader, a great CEO.

Published on October 20, 2019 09:02

August 22, 2019

The History and Geography of the Kashmir Problem

Image: Courtesy USA Today

Image: Courtesy USA TodayBooker prize winner and Human rights activist, Arundhati Roy, while addressing a seminar titiled "Whither Kashmir? Freedom or enslavement?” and organized by Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) in Srinagar in 2010, said, “Kashmir has never been an integral part of India. It is a historical fact.” It’s a matter of conjecture as to what India she was referring to and what history she had dug into. Let’s do some simple facts check.

First, let’s see what’s India.

The Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang (also written Xuanzang), who visited India in the seventh century (almost a millennium after Alexander) during the reign of Harshavardhana, rightly wrote, “It (India) was anciently called Shin-tu (Sindhu, the river), also Hien-tau (Hindu); but now, according to the right pronunciation, it is called In-tu (India)… The entire land is divided into seventy countries or so… Each country has diverse customs…” So India, according to him was a super country of seventy or so countries. I think that’s the most apt definition of India, as it has been since many millennia.

The Greek historian Megasthenes too, a millennium before, had referred to the “entire land” by one name – Indica. And the Persian polymath Al-Biruni, four centuries later, wrote the book Taḥqīq māli-l-hind min maqūlah maqbūlah fī al-ʿaql aw mardhūlah, Confirming (tahqiq) all Topics (maqul) of India (Hind), Acceptable (maqbul) and Unacceptable (mardhul), referring to India as Hind, in the 11th century. The Arabs still refer to India as Hind – the granularity of the provinces and languages and ethnicities are not visible from outside, as it has been over the past few millennia.

This country of countries, India, which appeared as a single homogeneous entity, seen holistically, was perhaps united administratively for the first time by Ashoka in the third century BC. Ashoka also created a large Asian Union comprising almost all the existing governments in South and South East Asia, enabling seamless trade and exchange of commodities, peoples and cultures across a very large area, something much more than the recent European Union.

During Ashoka’s time India was the largest economy comprising almost 35% of the world GDP. (China’s GDP was around 25% and that of the Greeks little more than 10%). India’s dominance in the world economy remained intact for the next two millennia, always maintaining a staggering 25-30% share of the world GDP, till the beginning of the 18th century, when the British arrived. There’s indeed a reason behind this.

In just 120 years, between 1700 and 1820, India’s GDP fell from 25% to 15% of the world GDP, and by 1947, when India was partitioned, it was at a mere 4%. So what exactly did the British do? They just broke the scaffolding which supported the Indian economy for millennia – the security of uninterrupted production and the safety of free trade across the entire subcontinent. They broke the federal structure of the subcontinent that functioned like an efficient and united country for millennia, and disintegrated it into isolated regions, cutting the seamless trade. The entire economy collapsed in no time. Suddenly the people of India were not allowed to produce and trade freely. Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy is the best chronicle of this devastation. People who had been cultivating their own food aplenty were suddenly forced to cultivate opium and indigo, and trade only with the British. Soon, for the first time, India saw hungry people, and famines.

India’s independence in 1947 didn’t do much good. The truncated India was severely bereft of the entire trade network which was the lifeline of her economy for more than two millennia. The “Kabuliwala” (immortalized by Tagore in a very poignant eponymous short story), the Afghans, who were household names in Bengal disappeared soon, like the Kashmiri shawl not much later, from Bengal and elsewhere. Free movement of people and trade collapsed between the frontiers.

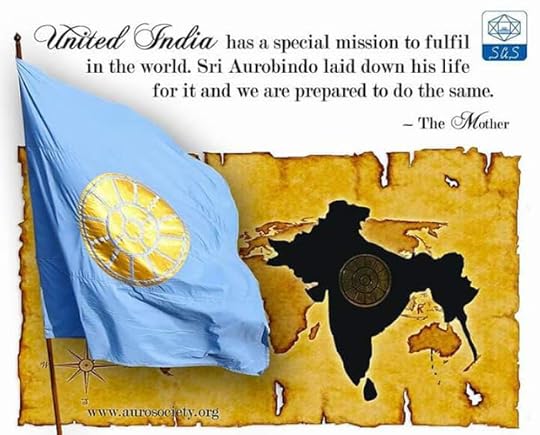

It’s not for no reason then, that Sri Aurobindo had cautioned on 15th August 1947, when India was portioned, and which was also his 76th birthday, “India today is free but she has not achieved unity… In whatever way, the division must go; unity must […] be achieved, for it is necessary for the greatness of India’s future.” It was therefore not a surprise to anyone in the know, when the spiritual flag of united India, designed by him, was hoisted at the Aurobindo Ashrama in Pondicherry after the Article 370 had been abrogated by the Govt. of India in order to integrate Kashmir completely into India. Aurobindo had wanted the flag to be hoisted whenever a separated part of India would rejoin, thus celebrating the idea of a united India.

Now let’s come to Kashmir.

Hiuen Tsang talked in length about Kia-shi-mi-lo (Kashmir) as one of the seventy Indian countries,“enclosed by mountains… The neighboring states that have attacked it have never succeeded in subduing it. The capital of the country on the west side is bordered by a great river.”

A verse from the Rig Veda, The Ode to the Rivers, (Book 10, Hymn 75, Verse 5) goes like this:

Shutudri stomam sachataa Parushni aa| Asiknyaa Marudvridhe Vitastayaa Aarjikiye shrinuhya aa Sushomayaa ||

O Shutudri (Sutlej), O Parushni (Ravi), [you] favor this hymn [of mine]. With Asikni (Chenab) [and] with Vitastaa (Jhelum), O Marudvridhaa (the combined river of Chenab and Jhelum); with Sushomaa (Sohan) O Arjikiyaa (upper Indus), hear [my hymn].All the major left tributaries of the Indus are enumerated in anti-clockwise manner, starting from Sutlej, barring Beas. It can be argued that the mere mention of Jhelum (Vitastaa) doesn’t mean that Kashmir was a part of the Rig Vedic India. But the fact that the ancient word Vitastaa is still preserved in Vyeth, the Kashmiri name for Jhelum, surely says something else. The very next verse talks about three rivers Trishtaamaa, Susartu and Sveti, which, from the order they are mentioned, could be very well the right tributaries of Indus in Kashmir, with a possibility that Sveti could be Gilgit. But much more striking, as the Harvard Indologist and Vedic scholar Michael Witzel has pointed out, is the fact that the Sanskrit word Sindhu, which gave the identity to India, her peoples and cultures, is very likely a loan word from the much older Burushaski language, remnants of which are still spoken in few isolated pockets of Kashmir. In the Burushaski, Shina and Dumaki languages of Kashmir “sinda” means river and that explains why there are multiple rivers in Kashmir with the name Sind (Sonmarg is on Sind).

The Greek historian Hecataeus, in his description of India, referred to Kashmir as Kaspapyros (surely related to Kashmir’s old name Kashyapapura, the city of the Rig Vedic sage Kashyapa), in the sixth century BC.

Rajatarangini, the first Indian book of secular history written by Kalhana in the 12th century, is a chronicle of the history of Kashmir and India since the time of the Mahabharata war. The 102nd and 104th verses of its first book says, Ashoka, who has killed all his sins, shaanta-vrijina, embraced the doctrines of Jina (Buddha), prapanna jina-shaasanam, built the city of Srinagari.

So the discourses on Kashmir not being a part of India can rest for ever. Like any other part of India, it has been, and should remain an integral part of India. Now let’s look back and try to analyze why there has been so much fuss about Kashmir’s special status since 1947.

When India was partitioned, most of her peoples were never asked which part they wanted to be in – India or Pakistan. Bengal and the Punjab were attempted to be partitioned allocating the Muslim majority areas to Pakistan and retaining the rest in India. But that left out numerous regions on either sides with contrasting demographics – Hindu majority areas in Pakistan and Muslims majority in India. People of these regions were never asked whether they were fine with their fates – especially the hapless minorities who decided to stay back in Pakistan.

Moreover, there were some major anomalies, all of which favored Pakistan. The whole of Khulna district of Bengal with 50.7% Hindu population was awarded to (East) Pakistan. To decide which country they wanted to join, Sylhet, a part of Assam, was offered a referendum, which was thoroughly rigged in favor of Pakistan. When plebiscite was offered to the princely states of Junagarh, Hyderabad and Jammu & Kashmir, Jinnah insisted that the decisions should be left to the rulers and not to the peoples, because he was more interested in Hyderabad, a Hindu majority princely state ruled by a Muslim, than J&K, exactly its opposite. Given this, Pakistan shouldn’t have had any problem when the Hindu king of J&K wanted to join India. Period.

So, from the very beginning Pakistan’s actions in matters of Kashmir were uncalled for. Their attacking Kashmir in 1947 in a bid to free it from India could be similar to India trying to free Khulna, Sylhet (in East Pakistan) and the North West Frontier Province (under Frontier Gandhi, they wanted to join India) from Pakistan, which very logically India never did. And for the millions of people who became victims of the partitions and who were not consulted before their fates had been decided by someone else, they learned to accept the eventuality and move on, building their lives from scratch. Extending the same logic to Kashmir, it would be ludicrous to even accept the argument that their accession to India was unjust. The accession, like any other part of India, should have been unconditional from the day one, just to maintain the parity with the rest.

The reality is, even the Kashmiris eventually learned to move on. Till the eighties there hasn’t been any disturbance. Not a single incident could be pointed out to vindicate that the Muslims in the valley were being subjugated by a Hindu majority India. On the contrary, the Kashmiri Pandits can’t remember since when they stopped celebrating any festival outdoor, fearing reactions from their Muslim “neighbors”. There was of course this dream of the two sides of Kashmir (J&K and POK) uniting someday, like many, who had to leave their homes in East Bengal and settle in India, still living with the utopia of a reunited Bengal. But that didn’t lead to any violence or terrorism, till Pakistan, in the eighties, started indoctrinating the youths in the valley, first with communism and revolution, with inspiration from Guevara, Castro, Nietzsche, Chomsky et al, and then slowly with radical Islamization.

Two elections in the eighties were rigged in Kashmir, but all elections in Bengal and Bihar have been rigged till the nineties. So, that was no justification for resorting to violence and terrorism, but it was very smartly exploited to begin with the ethnic cleansing of the Hindus and Sikhs in the valley.

Over six months, starting with the winter of 1989, the entire Pandit population was terrified with rampant killings and rapes, threatened with dire consequences and finally forced to leave, with the masjids announcing openly: Yetiy banega Pakistan, batav rosti batanivy saan, This will be Pakistan, without the Pandit men, but with their women; Raliv, Galiv, ya Tschaliv, Merge, Die or Flee. All the while, during this short period of six months, the Indian government kept silent, when chits were being pasted on the doors of the houses of the Kashmiri Pandits daily, announcing who should leave next. The present militarization of the valley was only after this.

The truth is that the issue has never been a fight for Kashmiriyat. It was always, like Pakistan, to do away with everything else than Islam, totally obliterate all the non-Islamic identities that have thrived for millennia and try to create, futilely though, an Islamic identity. It’s nothing but the popular slogan Iqbal had coined: Pakistan ka matlab kya la illaha illalah, which translates word by word to “Pakistan’s meaning is there is no god but Allah”. This obsession with carving out an Islamic identity, disowning the millennia old unalienable Indian history, heritage and connections is the root cause of Pakistan’s identity crisis, which explains why they are a failed state. Totally contrast to this is how the few other non-Arab Islamic countries like Bangladesh, Iran, Malaysia and Indonesia have so well preserved their non-Islamic rich cultural heritages.

The people who are spearheading all the “struggle” in the valley are least interested in Kashmiriyat. Most of them don’t even speak the language – they prefer Urdu, I’m told. During the Swadeshi movement, when the Indians wanted to boycott everything British, they didn’t slyly send their kids to Britain for education – they created their own institutions like Jadavpur University in Calcutta and Banaras Hindu University. On the contrary none of the separatists’ kids study in the valley. It’s also not about their hatred for India. Otherwise so many Kashmiris wouldn’t have had business interests across India, pointed out a Kashmiri Pandit friend of mine. A Chechen separatist, she added, would rarely enter into any business with Russia. A little fact check will reveal that nothing of Kashmiriyat has been preserved in POK, but still no Kashmiri separatist or activist ever talks about that.

Moreover, I myself figured out during my trip to the valley in 2017 that the minority Shias are not at all antagonized to India. Nor are the Hanzis, the boatpeople who are not part of the mainstream Islamic communities. Both these communities have been marginalized. Pehle Kafir (Hindus and Sikhs), phir Shia, phir Hanzi, that has been the agenda and the clarion call. The fact that the Shia majority Gilgit-Balistan in POK today has a totally different demographics should say it all.

It could be argued that India should have honored the special status given to Kashmir (in the form of Article 370) and promised as a part of the accession pact. But then, India did honor the commitment in spirit as the demographics in the valley didn’t change at all over the years (apart from the 100% exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits, for which of course the Indian government was not responsible) whereas that in POK did drastically. And as to honoring the commitment in letter, it’s up to the Supreme Court to judge if the abrogation of Article 370 really violated anything.

So practically, the entire issue about Kashmir is a Sunni Wahabi narrative perpetuated forcefully by a few with vested interests and supported by Pakistan. That’s the root cause of everything. It’s also perhaps, as pointed out to me by a Kashmiri friend of mine, a hidden agenda fueled by the racial supremacy of the ruling class of Pakistan, who didn’t want to share the power with the dark skinned and Bengali-speaking Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (he would soon become the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh) even though he had got a massive majority in the 1970 general elections in Pakistan, just because they felt he was racially inferior.

India has to put an end to all these. India needs to be united, not because she has been such all along, but because, that’s how she can survive longer, as a strong economy and a prosperous and free place.

The need of the hour is to gain the confidence of the indoctrinated Kashmiris and convince them that it’s for mutual benefit that we all stay together.

Published on August 22, 2019 11:19

August 20, 2019

Kashmir and the idea of a United India

Talking about nations, Tagore had said, “The peoples are living beings. They have their distinct personalities. But nations are organizations of power… Nations do not create, they merely produce and destroy.”

On 15th August 1947, two nations were “produced”, not created, but the India or Hindustaan or Bhaarata Varsha, thriving with its diverse peoples and cultures for many millennia, was destroyed.India can’t afford to be destroyed once again.

It’s not for no reason that Sri Aurobindo had cautionedon that day, which was also his 76th birthday, “India today is free but she has not achieved unity… In whatever way, the division must go; unity must […] be achieved, for it is necessary for the greatness of India’s future.” It was therefore not a surprise to anyone in the know, when the spiritual flag of united India, designed by him, was hoistedat the Aurobindo Ashrama in Pondicherry after the Article 370 had been abrogated by the Govt. of India in order to integrate Kashmir completely into India. Aurobindo had wanted the flag to be hoisted whenever a separated part of India would rejoin, thus celebrating the idea of a united India.

Tagore didn’t survive to see the birth of the two decapitated nations, much of his lands and people in East Bengal becoming part of a nation (Pakistan) he might not have been excited about. His anxiety at the partition of India might have been similar to that of Aurobindo’s. So, let’s try to understand the reason behind the anxiety, and at the same time, the idea behind a united India or Bhaarata Varsha.

Many people have often commented that India as a nation never existed and that it was the creation of the British. In the same breath it has also been claimed that India was never united till the British came to rule India in the eighteenth century.

Yes, India was never a “nation”, in the western sense, and in the sense Tagore had referred to it as “organizations of power”. India, Hindustaan or the more ancient Bhaarata has been rather a “varsha”, which literally means a “division of the earth” in Sanskrit. Bhaarata Varsha is then a place on earth peopled by disparately diverse human beings, with as much diverse cultures, languages, shapes and colors, but still having a very distinctive common aspect which made all of them look homogenous, when seen from a distance. This homogeneity, we will see, is nothing but the spiritual unity of the peoples of the entire landmass from the Gandhara (parts of present Pakistan and Afghanistan) in the west to Magadha (present Bengal-Bihar) in the east, from Kashmira in the north to the Dravida in the south.

Interestingly the Sanskrit term “varsha” in Bhaarata Varsha, the land of Bharata, is akin to “varshaa”, rains, implicating that the former would have come from the sense of the land of the rains that support the lives of its peoples. (It also means a period, a year, coming from the periodic nature of the rains). So, more than the power that rules a nation, it’s the rains, the symbol of life and growth, that signifies Bhaarata. With the same line of thought it can be realized that, it’s this “life” or rather the way of life of the diverse peoples of Bhaarata that has always appeared quite homogeneous to anyone external. That explains why despite the diversity, India has always been seen as one unit, one entity, which came about to be designated by the name of the mighty river anyone must come across the moment she stepped into India from the west – Sindhu, Indus, Hindu.

The first occurrence of the term “Hindu” as the designation of a land is found in the Avesta, the earliest scriptures of the Zoroastrians, written in a language very close to the Rig Vedic Sanskrit in Eastern Iran sometime around 1000 BC, where it appears as “Hapta Hendu”, the Avestan words for Sapta Sindhu, referring to the land of the Seven Rivers, which surely points to the undivided Punjab. Very soon various forms of the word “Hindu” came about to mean not only the Punjab, but the entire Indian subcontinent. By the time Alexander reached the Sindhu, in fourth century BC, Megasthenes, the Greek historian, started writing about the Indian history and when he completed he named his magnum opus Indica. It was just a matter of time that the Hapta Hindu became Hindustan, but it retained the same original meaning of Bhaarata Varsha – a sea of Great Humanity, Mahaa Maanava, as Tagore would put across.

India has always been diverse, disparate but still not disintegrated. The people from outside the subcontinent wouldn’t see the granularity. But in reality, even the Rig Veda (RV Book 7, Hymn 18), written not later than 1500 BC, talks about a Sudaas, the King of the Tritsu tribe and a descendant of the legendary Bharata the subcontinent eventually would be christened after, fighting against ten other tribes – Bhrigu, Druhyu, Turvasha, Paktha, Bhalaanas, Alina, Vishaanin, Shiva, Anu and Puru – and uniting them. Even during the time of the Rig Veda some of these tribes and their languages and cultures were so different from each other that the speech of the Purus appeared scornful, mriddhra, to others (RV Book 7, Hymn 18, Verse 13), and it was a matter of shock to some that the people of Kikata, perhaps Magadha of the later times comprising modern Bengal and Bihar, didn’t follow the ritual of preparing the milky draught, aashira, by heating it in the kettles (RV Book 3, Hymn 53, Verse 14).Till now we’ve been only talking about the spiritual unity – unity in the way of the lives of the peoples of India. But any form of unity that doesn’t result in the overall growth and prosperity of the humanity is meaningless. Talking about growth and prosperity, the topics like governance, economy, security etc. can’t be ignored. It was very clear at an early stage of our civilization that it was also essential to have a homogeneity in the governance, a uniformity in the administration. It was needed not for anything else, but to foster better trade and commerce between its every part and create a self-sustaining economy. This would eventually give the peoples enough safety and security to be “free” in the real sense, with the “strength to our activities and breadth to our creations”, as Tagore saidabout freedom.But what could have been the binding force to create this uniformity? Interestingly, it’s the inherent spiritual unity that would again bind the peoples, and it’s in this context that Buddha played a great role. In the Bengali period novel Maitreya Jaatak, centered around the life of Buddha and His interaction with Bimbisaar, the King of Magadha, the author Bani Basu very wonderfully recreated the times with the need and inspiration for such a political unification of the sub-continent. It might be controversial to say that Buddha was the main force behind the first political unification of India, but when we see that few centuries later Ashoka did exactly the same, using the teachings of Buddha as the master glue or the value proposition, we understand the role of Buddha. Ashoka not only unified the entire Indian subcontinent politically but also created a large Asian Union comprising almost all the existing governments in South and South East Asia, enabling seamless trade and exchange of commodities, peoples and cultures across a very large area, something much more than the recent European Union.So, along with the spiritual unity, India was now united politically and administratively. The popular narrative that Ashoka had a sudden change of heart after the devastating Kalinga war and that he henceforth wanted to tread the path of Dhamma (dharma) might be more of a calculated PR stint. In reality, everything might have been as per Chanakya’s (the ace economist and master strategist of Ashoka’s grandfather Chandragupta Maurya) game plan of controlling the economies rather than territories. Using Buddha’s doctrines of peace and happiness was no doubt a much more effective way of doing so, rather than indulging in wars and incurring heavy economic losses. Perhaps Buddha Himself wanted the same – uniting people through spirituality rather than warfare. And it did work. It worked again two millennia later, with Gandhi’s non-violence.During Ashoka’s time India was the largesteconomy comprising almost 35% of the world GDP. (China’s GDP was around 25% and that of the Greeks little more than 10%). India’s dominance in the world economy remained intact for the next two millennia, always maintaining a staggering 25-30% share of the world GDP, till the beginning of the 18thcentury, when the British arrived. There’s indeed a reason behind this.Jawaharlal Nehru pointed out a very interesting thing in his Discovery of India, about India’s dominance over the past two millennia. Since Ashoka’s time, he said, irrespective of the power (Kings or Emperors) at the helm, there was an unwritten thumb rule across the entire subcontinent that no warfare should ever destroy the crop and economy. It’s not for no reason that battles were always fought at designated desolate places, away from localities and cultivable lands, so as to minimize the collateral damage. Also, no warring Kings ever destroyed the Pan-India trading infrastructure that had existed since Ashoka’s time. So even though there were innumerable kingdoms and kings and emperors over the past two millennia, and as many battles, but when it came to trade and commerce, the entire subcontinent always behaved as though it were a single unified and uninterrupted market place. In fact, the people often didn’t even know who their rulers were. The entire Indian subcontinent functioned very much like a country with a single federal system whose sanctity and robustness was maintained not by the rulers, but by its peoples and at the center was the economy.The Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang (also written Xuanzang), who visited India in the seventh century (almost a millennium after Ashoka) during the reign of Harshavardhana, rightly wrote, “It (India) was anciently called Shin-tu (Sindhu), also Hien-tau (Hindu); but now, according to the right pronunciation, it is called In-tu (India)… The entire land is divided into seventy countries or so… Each country has diverse customs…” So India, according to him was a super country of seventy or so countries. Megasthenes too, a millennium before, had referred to the “entire land” by one name – Indica. And the Persian polymath Al-Biruni, four centuries later, wrote the book Taḥqīq mā li-l-hind min maqūlah maqbūlah fī al-ʿaql aw mardhūlah, Confirming (tahqiq) all Topics (maqul) of India (Hind), Acceptable (maqbul) and Unacceptable (mardhul), referring to India as Hind, in the 11th century. The Arabs still refer to India as Hind – the granularity of the provinces and languages and ethnicities are not visible from outside, as it has been over the past few millennia.In just 120 years, between 1700 and 1820, India’s GDP fell from 25% to 15% of the world GDP, and by 1947, when India was partitioned, it was at a mere 4%. So what exactly did the British do? They just broke the scaffolding which supported the Indian economy for millennia – the security of uninterrupted production and the safety of free trade across the entire subcontinent. They broke the federal structure of the subcontinent that functioned like an efficient and united country for millennia, and disintegrated it into isolated regions, cutting the seamless trade. The entire economy collapsed in no time. Suddenly the people of India were not allowed to produce and trade freely. Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy is the best chronicle of this devastation. People who had been cultivating their own food aplenty were suddenly forced to cultivate opium and indigo, and trade only with the British. Soon, for the first time, India saw hungry people, and famines.India’s independence in 1947 didn’t do much good. The truncated India was severely bereft of the entire trade network which was the lifeline of her economy for more than two millennia. The “Kabuliwala” (immortalized by Tagore in a very poignant eponymous short story), the Afghans, who were household names in Bengal disappeared soon, like the Kashmiri shawl not much later, from Bengal and elsewhere. Free movement of people and trade collapsed between the frontiers.

Moreover, the spiritual unity of India was broken forever. What became Pakistan is a very important

part of India’s cultural heritage and identity. The first urban Indian civilization in the Indus valley; Punjab, the place where the first book of the mankind – the Rig Veda – was written; Gandhara, one of the regions where Buddhism thrived for the longest in the subcontinent – all became Pakistan, which ironically went ahead to eradicate all the pre-Islamic identities and legacy. Thus, with the partition, not only was our economy crippled, a big part of our heritage was also left to die. More legacies would die if Kashmir or any other part of India is lost. We can’t let that happen. Let’s now turn our attention to Kashmir.Booker prize winner and Human rights activist, Arundhati Roy, while addressing a seminar titiled "Whither Kashmir? Freedom or enslavement?” and organized by Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) in Srinagar in 2010, said, “Kashmir has never been an integral part of India. It is a historical fact.” It’s a matter of conjecture as to what India she was referring to and what history she had dug into. Let’s do some simple fact check.

A verse from the Rig Veda, The Ode to the Rivers, (Book 10, Hymn 75, Verse 5) goes like this:

Shutudri stomam sachataa Parushni aa| Asiknyaa Marudvridhe Vitastayaa Aarjikiye shrinuhya aa Sushomayaa ||

O Shutudri (Sutlej), O Parushni (Ravi), [you] favor this hymn [of mine]. With Asikni (Chenab) [and] with Vitastaa (Jhelum), O Marudvridhaa (the combined river of Chenab and Jhelum); with Sushomaa (Sohan) O Arjikiyaa (upper Indus), hear [my hymn].All the major left tributaries of the Indus are enumerated in anti-clockwise manner, starting from Sutlej, barring Beas. It can be argued that the mere mention of Jhelum (Vitastaa) doesn’t mean that Kashmir was a part of the Rig Vedic India. But the fact that the ancient word Vitastaa is still preserved in Vyeth, the Kashmiri name for Jhelum, surely says something else. The very next verse talks about three rivers Trishtaamaa, Susartu and Sveti, which, from the order they are mentioned, could be very well the right tributaries of Indus in Kashmir, with a possibility that Sveti could be Gilgit. But much more striking, as the Harvard Indologist and Vedic scholar Michael Witzel has pointed out, is the fact that the Sanskrit word Sindhu, which gave the identity to India, her peoples and cultures, is very likely a loan word from the much older Burushaski language, remnants of which are still spoken in few isolated pockets of Kashmir. In the Burushaski, Shina and Dumaki languages of Kashmir “sinda” means river and that explains why there are multiple rivers in Kashmir with the name Sind (Sonmarg is on Sind).

We’ve seen earlier that the western travelers/historians always referred to India as a single country, despite the various countries within.

The Greek historian Hecataeus, in his description of India, referred to Kashmir as Kaspapyros (surely related to Kashmir’s old name Kashyapapura, the city of the Rig Vedic sage Kashyapa), in the sixth century BC.

Then, Hiuen Tsang in the sixth century AD talked in length about Kia-shi-mi-lo (Kashmir) as an Indian kingdom “enclosed by mountains… The neighboring states that have attacked it have never succeeded in subduing it. The capital of the country on the west side is bordered by a great river.”

Rajatarangini, the first Indian book of secular history written by Kalhana in the 12th century, is a chronicle of the history of Kashmir and India since the time of the Mahabharata war. The 102nd and 104th verses of its first book says, Ashoka, who has killed all his sins, shaanta-vrijina, embraced the doctrines of Jina (Buddha), prapanna jina-shaasanam, built the city of Srinagari.

So the discourses on Kashmir not being a part of India can rest for ever. Like any other part of India, it has been, and should remain an integral part of India. Now let’s look back and try to analyze why there has been so much fuss about Kashmir’s special status since 1947.

When India was partitioned, most of her peoples were never asked which part they wanted to be in – India or Pakistan. Bengal and the Punjab were attempted to be partitioned allocating the Muslim majority areas to Pakistan and retaining the rest in India. But that left out numerous regions on either sides with contrasting demographics – Hindu majority areas in Pakistan and Muslims majority in India. People of these regions were never asked whether they were fine with their fates – especially the hapless minorities who decided to stay back in Pakistan.

Moreover, there were some major anomalies, all of which favored Pakistan. The whole of Khulna district of Bengal with 50.7% Hindu population was awarded to (East) Pakistan. To decide which country they wanted to join, Sylhet, a part of Assam, was offered a referendum, which was thoroughly rigged in favor of Pakistan. When plebiscite was offered to the princely states of Junagarh, Hyderabad and Jammu & Kashmir, Jinnah insistedthat the decisions should be left to the rulers and not to the peoples, because he was more interested in Hyderabad, a Hindu majority princely state ruled by a Muslim, than J&K, exactly its opposite. Given this, Pakistan shouldn’t have had any problem when the Hindu king of J&K wanted to join India. Period.

So, from the very beginning Pakistan’s actions in matters of Kashmir were uncalled for. Their attacking Kashmir in 1947 in a bid to free it from India could be similar to India trying to free Khulna, Sylhet (in East Pakistan) and the North West Frontier Province (under Frontier Gandhi, they wanted to join India) from Pakistan, which very logically India never did. And for the millions of people who became victims of the partitions and who were not consulted before their fates had been decided by someone else, they learned to accept the eventuality and move on, building their lives from scratch. Extending the same logic to Kashmir, it would be ludicrous to even accept the argument that their accession to India was unjust. The accession, like any other part of India, should have been unconditional from the day one, just to maintain the parity with the rest.

The reality is, even the Kashmiris eventually learned to move on. Till the eighties there hasn’t been any disturbance. Not a single incident could be pointed out to vindicate that the Muslims in the valley were being subjugated by a Hindu majority India. On the contrary, the Kashmiri Pandits can’t remember since when they stopped celebrating any festival outdoor, fearing reactions from their Muslim “neighbors”. There was of course this dream of the two sides of Kashmir (J&K and POK) uniting someday, like many, who had to leave their homes in East Bengal and settle in India, still living with the utopia of a reunited Bengal. But that didn’t lead to any violence or terrorism, till Pakistan, in the eighties, started indoctrinating the youths in the valley, first with communism and revolution, with inspiration from Guevara, Castro, Nietzsche, Chomsky et al, and then slowly with radical Islamization.

Two elections in the eighties were rigged in Kashmir, but all elections in Bengal and Bihar have been rigged till the nineties. So, that was no justification for resorting to violence and terrorism, but it was very smartly exploited to begin with the ethnic cleansing of the Hindus and Sikhs in the valley.

Over six months, starting with the winter of 1989, the entire Pandit population was terrified with rampant killings and rapes, threatened with dire consequences and finally forced to leave, with the masjids announcing openly: Yetiy banega Pakistan, batav rosti batanivy saan, This will be Pakistan, without the Pandit men, but with their women; Raliv, Galiv, ya Tschaliv, Merge, Die or Flee. All the while, during this short period of six months, the Indian government kept silent, when chits were being pasted on the doors of the houses of the Kashmiri Pandits daily, announcing who should leave next.

The present militarization of the valley was only after this.

The truth is that the issue has never been a fight for Kashmiriyat. It was always, like Pakistan, to do away with everything else than Islam, totally obliterate all the non-Islamic identities that have thrived for millennia and try to create, futilely though, an Islamic identity. It’s nothing but the popular sloganIqbal had coined: Pakistan ka matlab kya la illaha illalah, which translates word by word to “Pakistan’s meaning is there is no god but Allah”. This obsession with carving out an Islamic identity, disowning the millennia old unalienable Indian history, heritage and connections is the root cause of Pakistan’s identity crisis, which explains why they are a failed state. Totally contrast to this is how the few other non-Arab Islamic countries like Iran, Malaysia and Indonesia have so well preserved their non-Islamic rich cultural heritages.

The people who are spearheading all the “struggle” in the valley are least interested in Kashmiriyat. Most of them don’t even speak the language – they prefer Urdu, I’m told. During the Swadeshi movement, when the Indians wanted to boycott everything British, they didn’t slyly send their kids to Britain for education – they created their own institutions like Jadavpur University in Calcutta and Banaras Hindu University. On the contrary none of the separatists’ kids study in the valley. It’s also not about their hatred for India. Otherwise so many Kashmiris wouldn’t have had business interests across India, pointed out a Kashmiri Pandit friend of mine. A Chechen separatist, she added, would rarely enter into any business with Russia. A little fact check will reveal that nothing of Kashmiriyat has been preserved in POK, but still no Kashmiri separatist or activist ever talks about that.Moreover, I myself figured out during my trip to the valley in 2017 that the minority Shias are not at all antagonized to India. Nor are the Hanzis, the boatpeople who are not part of the mainstream Islamic communities. Both these communities have been marginalized. Pehle Kafir (Hindus and Sikhs), phir Shia, phir Hanzi, that has been the agenda and the clarion call. The fact that the Shia majority Gilgit-Balistan in POK today has a totally different demographics should say it all.

It could be argued that India should have honored the special status given to Kashmir (in the form of Article 370) and promised as a part of the accession pact. But then, India did honor the commitment in spirit as the demographics in the valley didn’t change at all over the years (apart from the 100% exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits, for which of course the Indian government was not responsible) whereas that in POK did drastically. And as to honoring the commitment in letter, it’s up to the Supreme Court to judge if the abrogation of Article 370 really violated anything.

So practically, the entire issue about Kashmir is a Sunni Wahabi narrative perpetuated forcefully by a few with vested interests and supported by Pakistan. That’s the root cause of everything. It’s also perhaps, as pointed out to me by a Kashmiri friend of mine, a hidden agenda fueled by the racial supremacy of the ruling class of Pakistan, who didn’t want to share the power with the dark skinned and Bengali-speaking Sheikh Mujbur Rahman (he would soon become the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh) even though he had got a massive majority in the 1970 general elections in Pakistan, just because they felt he was racially inferior.

India has to put an end to all these. India needs to be united, not because she has been such all along, but because, that’s how she can survive longer, as a strong economy and a prosperous and free place.

The need of the hour is to gain the confidence of the indoctrinated Kashmiris and convince them that it’s for mutual benefit that we all stay together.

Published on August 20, 2019 07:46

June 4, 2019

Why is there so much fuss about Hindi?

From time to time the diatribe against the imposition of Hindi on non-Hindi speaking people of India has become a sort of fashion, or rather a political weapon, to be flashed in public in order to flaunt nothing but a form of hollow chauvinism – it could be termed anything like provincial, regional, linguistic, ethnic, etc. – and mislead the innocent people with a fake sense of psychological safety against an imperial or federal onslaught. For reasons better known than often told, Hindi has been seen as a symbol of imposition and a threat to the pluralistic identities of India.

But strangely, the same threat is not felt for English, which, warns the prominent French linguist Claude Hagege, “may eventually kill most other languages". That itself says a lot about all these protests. These are just selfish acts of politics “concerned with the self-interest of a pugnacious nationalism”, to use Tagore’s apt words. I dragged Tagore into this because his views about “nationalism” are perhaps the most practical and relevant ones, even today. The “nationalism” he has referred to would be very clear from what he has to say about “nation”.

“We have no word for Nation in our language,” he clarifies. “When we borrow this word from other people, it never fits us… Not for us, is this mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches…”

Orgy of midnight, with lighted torches? Did the poet have a premonition of all the candle-lit vigils at the India Gate?

We will come back to Tagore. For now, let’s talk about something more recent. The moment the draft of the National Education Policy 2019 was made public, “lighted torches” came out in the night, accusing of, the same thing – imposition of Hindi.

I actually went through the draft.

It says, “Because research now clearly shows that children pick up languages extremely quickly between the ages of 2 and 8, and moreover that multilingualism has great cognitive benefits to students, children will now be immersed in three languages early on, starting from the Foundational Stage onwards.”

It then goes on elaborating the Three Language Formula: “[It] will need to be implemented in its spirit throughout the country, promoting multilingual communicative abilities for a multilingual country. However, it must be better implemented in certain States, particularly Hindi Speaking States; for purposes of national integration, schools in Hindi speaking areas should also offer and teach Indian languages from other parts of India. This would help raise the status of all Indian languages…”

What’s offensive in this? I don’t see any.

Just in case people think that the draft came from some arbitrary people, it must be reminded that the chairman of the committee is none other than K. Kasturirangan, former Chairman of ISRO. Few members are Vasudha Kamat, former Vice-Chancellor of the SNDT Women's University, Bombay, Manjul Bhargava, R. Brandon Fradd Professor of Mathematics at the Princeton University, USA, Mazhar Asif Member, Professor at the Centre for Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and others. I don’t think these people could be categorized into any genre of arbitrariness.

In case people have second thoughts about the benefits of multilingualism, let’s consider these.

Brainscape, committed to improving how the world studies, using the latest cognitive science research, has cited many benefits of being multilingual. Multilingual people, they say, tend to be more effective communicators. Multilingualism can even delay the onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease by an average of five years! Multilingual people better perform on tasks that require high-level thought, multitasking, and sustained attention. Perhaps this is why they are often seen as more intelligent than peers with similar innate intelligence, education, and background. They tend to solve complex problems in more creative ways than their monolingual peers, no matter what kind of problem is being solved. They are faster learners, more likely to make rational decisions, keen observers of the world around them, and more skilled at identifying and correctly analyzing the sub-context of a situation and interpreting the social environment.

An article in The Guardian says, multilingualism has been shown to have many social, psychological and lifestyle advantages.

To the question whether we should raise our children to be multilingual, The British Academy says, “My answer is an unconditional yes.”

In addition to facilitating cross-cultural communication, a paper says, multilingualism enables children as young as seven months to better adjust to environmental changes and seniors to experience less cognitive decline.

So I believe the question why three languages should be taught from early days is answered quite well. Let’s move on to the most important thing – the explosive topic of learning Hindi for non-Hindi speaking people.

Let’s rewind a bit. In 1918 Gandhi wrote a letter to Tagore asking if Hindi could be the “possible national language for inter-provincial intercourse in India”. Tagore’s answer was very interesting. “Of course Hindi is the only possible national language for interprovincial intercourse in India,” he asserted. “But… I think we cannot enforce it for a long time to come. In the first place, it is truly a foreign language for the Madras people, and in the second, most of [us] will find it extremely difficult to express [ourselves] adequately in this language for no fault of [our] own. So, Hindi will have to remain optional in our national proceedings until a new generation… fully alive to its importance, pave the way towards its general use by constant practice as a voluntary acceptance of a national obligation.”

Almost 20 years later, in 1937, Tagore wrote to Gandhi, “It is imperative … to organize an all-India movement to foster and spread the growth of a language which is potentially capable of being adopted as a common medium of communication between the different provinces… However, I hope that the language which is to claim allegiance as the lingua franca will prove and maintain its complete freedom from any communal bias…”

Intentionally I didn’t cite any or Gandhi’s words in favor of a lingua franca for India, because I felt, Tagore’s views are more universal in many aspects, and hence shouldn’t be colored either with left or right. Interestingly, Gandhi, who went a long way fighting for Hindi to be made as National Language (which hasn’t been ever implemented), and Tagore, both were non-Hindi speakers. But still they felt the need of a lingua franca, which has more relevance to trade and commerce than anything else. If the provinces were to stay in isolation, then there wouldn’t be the need for any lingua franca. But then, no province can grow in isolation. Unless there’s exchange of money and mind (thoughts), no race, province, nation can ever grow. And the first step for such an exchange is a common language, a lingua franca.

Neither Gandhi nor Tagore could be accused of anti-colonialism in not choosing English as the lingua franca. Whoever thinks that as an option is surely not a practical person. It’s ludicrous to think that a mason from Bengal and working at a construction site in Gujarat would bargain in English with the local fisherman, or, a Central Government employee from Madras, transferred to Assam, would teach the local cook, in English, how to make good sambar. It’s a no brainer that, even now, more than hundred years after Tagore had written that letter to Gandhi in 1918, Hindi is still the most likely solution to Tagore’s lingua franca for cross communication between provinces.

Many centuries ago, even the Mughals had felt the need of a lingua franca, for better administration and trade across the vast country of many races and languages. They too chose the prevalent Hindustani language of the day as the lingua franca. Of course they introduced a lot of Persian and Arabic words of administrative and judicial use. Thus, the Sauraseni Prakrit language of the medieval India, the immediate ancestor of Hindi during the first millennium, got a little different flavor in the second millennium, which later took the name Urdu, perhaps coming from the word vardi, meaning uniform, implicating that the language was nothing but a lingua franca for the people in uniform – either in the army or government jobs. Like Gandhi and Tagore, wisdom prevailed among the Mughals – they didn’t try to make Persian, their preferred language, the lingua franca. Persian, like English, stayed the official language for education, art and literature, whereas the lingua franca was the native Hindustani-Urdu.

More than two millennia ago, Ashoka too had a lingua franca – a form of the Magadhi Prakrit language (forefather of Bengali) spoken in Magadha, comprising present day Bihar and Bengal, Ashoka’s native. It might be relevant to note that in all of Kalidas’ Sanskrit dramas, the dialogues of the common people – the artisans, peasants, fishermen, even thieves – were always in Magadhi Prakrit, wherever they would be from. The only plausible reason for this could be that, Magadhi Prakrit was indeed the lingua franca of the common people across the country.

Ashoka’s rock edicts, few of which have survived till date across the Indian subcontinent, from Kandahar in Afghanistan to Bangladesh, from Delhi to Karnataka, had local variants of the Magadhi Prakrit, depending of the location, very much like the present day lingua franca, Hindi, which is spoken in different variants in different parts of India. The caricature and type cast of the Hindi spoken by the Bengalis and the South Indians, as immortalized in Bollywood by Asit Sen/Keshto Mukherjee and Mehmood respectively, says all about lingua franca – it’s more of a sort of an assortment of a number of mutually intelligible creoles rather than any uniform grammatically correct language. You like it or not, Hindi has already acquired that stature and no other language can replace that, how much ever “mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches” you do!

Going further back, even during the times of the Indus Valley Civilization, in the second and third millennia BC, the entire Central Asia, the melting pot of civilizations, races, cultures and languages, extending into parts of northwestern India, is believed to have had a lingua franca – the Burushaski language, vestiges of which now exist only in a few villages in Kashmir. Quite interestingly, the word Sindhu, the eponymous river which lent the names and identities to India, Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan, and even Indonesia (literally meaning Indian Islands), and the far off Indians of the Americas and the West Indies, is of Burushaski origin – it has survived as a linguistic fossil of the once grand language and the lingua franca of the most important locus in the annals of human civilization.

Lingua franca is the foundation for growth and prosperity, without which, the people survive in isolation, without any interaction and exchange of mind and money. Bangalore reaped the benefit of exchange, as it was never averse to the lingua franca, Hindi, and hence attracted labor and talent pool from all across India, thus boosting the growth of the city. From a sleepy pensioner’s paradise even thirty years back, it’s now the forth richest city in India (with respect to overall contribution to GDP, after Bombay, Delhi and Calcutta), much ahead of Madras, which is still averse to Hindi. Not many people would feel comfortable relocating to Madras. But no one would have a second thought about Bangalore. Almost the entire construction industry in Bangalore is supported by laborers from Bihar, Bengal and Orissa, as is the new age IT, ITES and BT industries by people from all across India.

Despite all the hullabaloo about “Bombay for Marathas”, Bombay is still the most cosmopolitan city in India, attracting people from all walks of life – Bollywood is the biggest example. Bombay’s like a miniature India, and not surprisingly, the lingua franca is Hindi. No wonder it’s the richest city in India. Calcutta too, till very recently when the CM started talking about the Hindi speaking outsiders, was never averse to Hindi and outsiders from any part of India. That corroborates its position as the third richest city in India.

It’s not for nothing that the Tamil speaking Shiv Nadar, co-founder and present Chairman of the USD 8.5 billion HCL, famously said that Hindi shaped his career. He even asked students in Tamil Nadu to learn Hindi. Knowing Hindi immediately breaks many social barriers. In one moment, everyone becomes a member of a single large fraternity, irrespective of the backgrounds, castes, creeds. I realized this the best the moment I landed in Kharagpur, at the IIT. The initial discomfort in communicating in Hindi was overcome soon and I slowly started speaking a heavily accented Bong version of Hindi – not much different from how Bollywood depicts. Everyone at the IIT knew English, but it was only in Hindi that we could share the camaraderie and bonhomie which remained with us forever. The same level of jokes and jibes and fun and frolic is unthinkable in English, not because it’s incapable of the same level of humor, but because it perhaps lacks the mitti ki khushboo, the smell of the Indian soil which only a highly agile and extremely fluid variant of Hindi (or Hinglish, whatever you may call) has.

It’s quite clear that anyone who would be averse to learning the lingua franca would do more harm to the community or fraternity than any good. Relevant are Tagore’s words, again. “Swaraj is not our objective,” he says, in criticism to the overt “nationalism” during the pre-independence era. “Our fight is a spiritual fight, it is for Man. We are to emancipate Man from the meshes that he himself has woven round him — these organizations of National Egoism.” Language chauvinism is just another organization of egoism, nothing else, and the protectionism of the language in the name of nationalism is nothing but the “meshes … woven around”. Tagore adds, “The butterfly will have to be persuaded that the freedom of the sky is of higher value than the shelter of the cocoon.” Any sort of protectionism is nothing but sad attempts at keeping people in cocoons.

The very thought that a language would be threatened by Hindi is nothing but demeaning that language, trying to protect the language in a cocoon.

That’s bondage.

That’s like breaking the world “into fragments by narrow domestic walls”.

Published on June 04, 2019 12:01

June 2, 2019

Not Islamophobia, it was the Hindutvaphobia of the opposition which attempted futilely to divide the country

Just after the results of the General Election 2019 were out, all hell broke loose among a section of people and media, who had expected very badly an anti-BJP government to come to power. Their hatred for BJP and Modi is so great that they were fine even with the directionless and narrative less Congress and the motley group of corrupt politicians like Lallu, Mayawati, Mulayam and many more, all of whom have dismal records when it comes to human rights, safety and development, forget corruption.

Someone said, “India is a full blown fascist country. Its transformation to fascism is now complete. Majority of Indians that voted this fascist political outfit are fascists. Once we recognize these basic facts, we can begin considering appropriate strategic responses to India and Indians…”

Someone else made a clarion call, “Those friends who are still sane, still believe in love and solidarity, like my friends in Calcutta, shall we walk the street tomorrow, in a walk where we talk about togetherness, sing about love, standing with our neighbors who speak to different Gods? This day is so disheartening, scary, unnerving!”

A major media house in the west scared the hell out of everyone. “Intoxicating voters,” it cried, “with the seductive passion of vengeance, and grandiose fantasies of power and domination, Mr. Modi has deftly escaped public scrutiny of his record of raw wisdom… He triumphantly reaped one of the biggest electoral harvests of the post-truth age, giving us more reason to fear the future…”

Fascism might be an understatement. What had been the narrative of a section of people, obsessed with liberalism and secularism, was actually a myth about Hindutvaphobia, a fear of a mysterious demonic entity that would devour the whole country and regress her to the stone ages of violence and darkness. It was as though, a group of illiterate and uncouth people from the hinterlands of India, without any basic wisdom and knowledge of Indian culture and civilization, of what all India stands for – things like pluralism, inclusiveness, etc. – have suddenly occupied the hallowed seats of power, of course through deceit and magic, and want to unleash their frenzied dark energies into the society and take full control over the lives and ways of the country’s elite and intellectuals, who have taken to themselves the grandiose task of maintaining the secular fabric of the country and upholding all the values and righteousness they have been custodian of, since God knows when.

Rarely has there been such vicious attacks, by a section of the media and intelligentsia, on the people in power, purely because the latter doesn’t align with the ideologies and thoughts of the former. And lo, the former are the ones who talk about liberalism and tolerance, where as they come about as the most intolerant to anyone who wouldn’t belong to their fraternity. Not only upon the BJP, the ire of the former very soon fell upon everyone who voted them back to power, again. So, the 38% of the Indian electorate became “fascists” and gullible of being “intoxicated” and “seduced by passion of vengeance”.

Overnight, the Modi haters came up with theories of massive consolidation of the Hindu votes against the myth of Islamophobia, allegedly purported by the BJP. In doing so, they totally ignored the real reasons behind Modi’s stupendous win. Rather, I would say, they were so blind in their own vision that they couldn’t see the realities on ground.

In the 2019 General Election, BJP has got around 38% vote share and 303 or 53% of the total seats, against Congress’ 20% vote share and 52 or 9% seats. In fact, in the seats where BJP contested, its vote share was as high as 46%.

With 37.6% vote share in rural constituencies, BJP has improved its performance in non-urban areas by close to 7%. In the seats it contested in rural areas, its vote share was close to 46%, compared to Congress’ 23%. This is totally in contradiction to the stories of rural distress, propagated so much by the opposition. I don’t imply here that there was no rural distress at all, but I do have reasons to say that the rural electorate did see some value in getting BJP or rather Modi back to power, if not we accept the ridiculous proposition, put forward by many, that Indians don’t know what they have done.

BJP has got 42% votes from the least (quartile) educated and around 40% from the least prosperous people in India, improving its tally with the latter by almost 30%.

It has improved its vote share in the SC and ST constituencies by 6-7%. It has got 11% more votes from areas with significant Dalit population. More people from the Adivasi dominated areas have voted for BJP than they did in 2014.

Interestingly, BJP has increased its vote share by close to 10% in areas with 20-40% Muslim population. Overall, around 11% Muslims have voted for BJP in 2019, compared to 8% in 2014, which is a close to 40% improvement. For instance, the vote share of BJP has increased by 5-10% in the Muslim dominating Shivajinagar, Chamarajpet and Shanthinagar assembly constituencies in Bangalore, compared to 2014.

Close to 50% of the GenZ population (born after 1996), all first time voters, have opted for BJP.So, BJP has been accepted over a large spectrum of electorate.

A little engagement with the masses would have made it very clear what the pulse of the nation was before the election. Few anecdotes would make things very clear.

One day, a month before the election, my wife had asked me if I knew anything about a scheme called Saubhagya. I vaguely remembered the name – one of the many schemes launched by Modi in the past five years. I asked her the context. She said that our maid, Kamala, had given her a lecture in the morning about many such schemes – she managed to remember only one name. What I figured out was that, Kamala was actually trying to “sell” Modi to my wife, because she had an inkling that the “rich” people, perhaps not among the beneficiaries of any of Modi’s schemes, might not bring him back at the helm of everything once more. She was worried that they, the “poor” people had lot to lose if Modi didn’t come back to power. Kamala is from a village in Karnataka, not far from Bangalore.

The next day I asked my driver, Sunil, whom he would vote for. He proudly told me that he hails from the same village as Aravind Limbavali, the BJP MLA from Mahadevpura, the assembly constituency we are part of. He pleaded me to vote for BJP. I asked him why he liked BJP so much. He requested me to come to his village and find it out myself. His village, he claimed excitedly, is not much different from the place we stay in Bangalore. Many roads there, he said, were better than Bangalore. Few days later he flashed his RuPay debit card. He also talked about the new LPG connection at his house. He was proud that he too had the privileges which had been merely aspirational to “them” in the past, privileges which only the “rich” in the cities had, but were now a reality even in his village.

Both Kamala and Sunil felt they were empowered.

Last year, I’d been to Delhi for some work and I’d taken a cab on rent for day. I have the habit of chit chatting with the cab drivers as I always get to know a lot of interesting facts and figures from them – the facts which are generally not published in the main stream media. I asked him what did he think about Yogi Adityanath’s government in UP, now that it was almost a year since he had come to power. He smiled sarcastically and sneered at me. “You, the educated lot,” he mocked, “you won’t understand.” That was rather rude, I felt. “The police have started working finally [in UP],” he said. “Isn’t that a badi baat, a big thing?” I remembered, some time ago another cab driver too had told me a similar thing about the Delhi cops. “Since Kejriwal becamethe CM,” he had told me, “we’re no longer harassed by the police. I have the number of my MLA – the son-of-a-bitch-police know very well that I can call him anytime…”For the lesser privileged, or rather the “poor”, I realized, the taming of the police was also a sort of empowerment – it gave them a sort of psychological safety.

After the 2019 General Election, when I was trying to figure out what magic had Modi done, I remembered Kamala and Sunil and the Delhi cab drivers. The empowerment came in various forms.

15 Million people have subscribed for the Atal Pension Yojana, a government co-contribution scheme to assure a monthly income up to INR 5000 after the age of 60, for all employees in unorganized sector.

There are around 360 Million beneficiaries of the Jan Dhan Yojana, one of the earliest welfare schemes launched by Modi. It’s a massive financial inclusion scheme, which starts with a bank account, a RuPay debit card, an INR 5000 overdraft facility and an INR 1 Lakh accident insurance. The main usefulness of this scheme is actually the immediate transfer of all benefits from the government directly to the account holders, by-passing any middleman. More than USD 100 Billion worth of benefits have been already transferred till date directly to the account holders.

Close to 60 Million have subscribed to the Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojona, an insurance scheme for all account holders, with a premium of roughly INR 1 per day, and a life coverage of INR 2 Lakh.

1.5 Lakh Km of roads have been constructed in villages across India, under the Gram Sadak Yojana. Commuting to and from a village to the nearest big hospital or school or workplace at a town closely is no longer a tyranny of fate.