Brett Shavers's Blog, page 6

April 6, 2024

Let me break your mind, DFIR.

TL:DR (too long; didn't read) The DFIR Investigative Mindset book is available on Amazon now at https://amzn.to/4apGxAX. The book launch ended on Day 2 with 400 copies sold in the book launch, with an additional 1,279 copies ordered from A...

March 29, 2024

"DFIR Investigative Mindset" Release Hits a Snag - Here's What's Up

So, you've been counting down the days until you could get your hands on "DFIR Investigative Mindset," right? March 22 was marked in your calendar, and if you've been wondering why you can't purchase what's intended to be a must-read in the digital f...

March 5, 2024

The most innovative DFIR book in a decade is coming

Yes, that is a big claim, but it is true. And it is not the book that I have coming out next month. The book coming out next month was practically finished last year but not wrapped up because of being busy. Stepping into the Breach The ...

January 26, 2024

The most neglected skill in DFIR is….

The one that is just as important as any technical skill: The DFIR Investigative Mindset. Personally, I’ve been harping on this concept since 2013. It has been written about as early as 2005 as “investigative mindset”, and written about using differe...

January 19, 2024

ChatGPT destroys the planet

I read an article today about a “writer” who used ChatGPT to write their book. A little further digging found that apparently, there are hundreds of books on Amazon that are written by AI and marketed as such. I can only imagine how many “writers” th...

July 7, 2018

Snap! Oh no you didn't.

Reading through the paper“Forensic framework to identify local vs synced artefacts” from DFRWS 2018 Europe, I came across a paragraph with several statements that I had to read twice, actually several times. The paper cited a book that I wrote in 2013 (Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard). The paper states:

“…he fails to make any reference to the challenge that will result from attributing data to a specific device.."

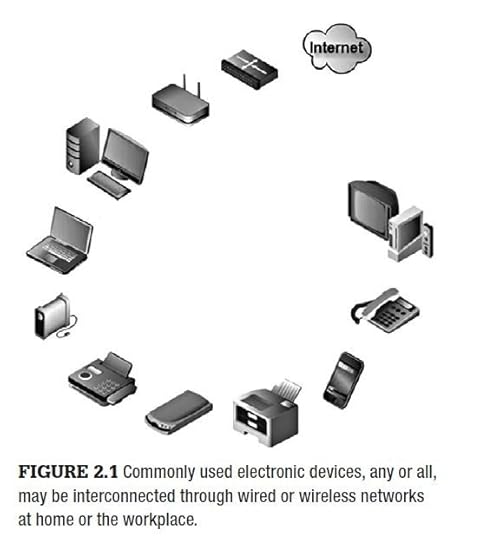

Actually, back in 2013, in that cited book, that was exactly what I wrote about: the challenges of not only attributing activity of a user to a device, but the activity and data of interconnected devices. Then I read...

“Shavers does not raise the challenge of trying to determine on which device the data was created is consistent with what we have seen in the computer forensic community.”

I respectfully disagree with the premise that the forensic community has not been trying to determine which device data has been created. Even going back way before 2013, metadata has been paramount to every case, from all evidence devices, connected to each other or not. As soon as mobile devices became connected to other devices, correlating the data between devices became something done as manner of practice. To state that “It is something that computer forensic examiners are not even considering in many cases” is foreign to me. One of the major points of my first book was to instill the concept that electronic evidence needs to be integrated with the physical world to make a complete case (or more eloquently, paint a beautiful picture).

Oh well. They must have missed those pages about inteconnected devices...and the pictures of interconnected devices too...

Today’s lesson, “Interconnected Devices and Your Investigations”

There are two things to consider with interconnected devices in your investigations:

1) Do the forensics independently on each device

2) Correlate the evidence you find from all the devices

That’s it. There isn’t much more to the secret other than forensics in/on the cloud. Interconnected devices may likely have data contained in the cloud (it’s how the data propagates between devices…). But even then, correlating the data between devices is no more difficult than the forensic work you do on each device.

Here is a visual figure from Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard, where I show a visual of a circle of interconnected devices. Every case you do, you should be thinking about this circle that revolves around your suspect (or custodian). It is constant and ever-changing with new and newly replaced devices. Keep this in mind as we continue.

The “I didn’t sync that file to my phone” defense

Let’s take a scenario of finding evidence on a mobile device that is synced to other devices (and the cloud) through a service like Dropbox. Finding the evidence on the mobile device, which was seized from the suspect, in which only the suspect ever had control, generally ties that evidence to the suspect. The possibility that a defense of that mobile device evidence being unknowingly synced to the device would be solely dependent upon if any other person has access to accounts that sync data, such as two persons with admin rights to the same Dropbox account. Meaning, if the suspect is in sole control of the Dropbox account, then the synced files are his. If not, maybe they are and maybe they are not. You need to dig a little more to be sure.

The “Someone else searched that on my home computer” defense

Internet browsing synching is cool. You can bookmark something on your home PC, it gets synched to your tablet, and also gets synched to your smartphone. Cool. However, if browsing history is the evidence found on the tablet, it might be important to know if the evidence was synced from another device if other persons had access to the other devices. Conversely, if the suspect has sole control of all devices, then the defense claim is moot as only the suspect had physical access to all devices (or is the only person with the creds to log into the devices). There is a trend here: he who controls the devices is generally going to be the possessor of the evidence found on those devices.

Ease your mind by doing a little extra work

With every case I have ever done, I have always wished that I had more time to work it. No matter if I worked 10 hours on a case or 10 thousand hours, I can work a case forever because I want to make sure I got it right. With that, you can probably tell that I love interconnected devices in a case because it gives me corroboration of what I found on other devices in a case. Even evidence files that are not synched between devices are great finds to corroborate findings and suspect’s intentions.

A lack of activity can be an indication of activity

Smartphones are great for historical activity. If Google is turned on (as in, logging everything you do), you can recover a great deal of geolocation data, which can be accessed through Google without even having the device in hand. This is a great tool for investigators. Just as cool is that for criminals who leave their phones at home when they are criming* in town, even a log of missed calls can give an indication that perhaps the suspects weren’t actually home with their phone since no one answered any of the incoming calls…or logged into email…or surfed the net…all while a bank robbery or drug deal was happening downtown… Historical activity is great to place suspects at a scene, and a complete lack of activity can give indications they were not where they said they were.

Circles of non-interconnected devices can be connected to each other

One suspect with multiple devices is easy enough to put together. Examine all the devices in the suspect’s circle of interconnected devices and put together a timeline of the important data points. But here comes the really fun part: In some cases, you have several suspects and each suspect has his own circle of interconnected devices. This type of case gives you a world of opportunities to reconstruct history by combining each suspect’s circle of interconnecting devices into one glorious timeline.

I’ve done this type of case on few occasions and assisted others. Without doubt, it is an immense amount of effort that exponentially increases with every device. In one particular case, we had a big box of smartphones was seized. The case revolved mostly around geolocation and text messages. The end result was that each phone geolocations were matched to a person, and the text messages matched between phones. Those with multiple phones had the identical geolocation on their phones, indicating they were carried together. The timeline of criminal activity was superimposed over the geolocation of each device along with text messages sent/received by geolocation. I can tell you that there are a group of criminals who will forever hate mobile devices because of this work.

We simply connected a circle of interconnected devices to other circles of interconnected devices and let the data paint the picture of what happened. Very cool. And you can do it too.

*the act of committing crimes, “criming”

June 27, 2018

Old hat investigative work will always work

The Reality Winner case is good example where a basic investigative method still works regardless of how much publicity that the same method has received for years prior. In the Winner case, printed documents were tied to Winner based on “microdots”. This article below does a decent job of explaining what micro dots are if you haven’t heard of this before, or if you associate microdots with LSD...

https://www.grahamcluley.com/reality-winner-pleads-guilty-after-being-unmasked-by-microdots/

Basic (and non-secret) investigative methods suceed more often than not, and actually happens all the time. It doesn’t really matter that criminals know police investigative methods, because the methods still work. A personal example that I had when I was doing drug investigations, was ‘knock-and-talks’, where my partner and I would knock on the door of a suspected drug dealer and ask consent to search for drugs. On one knock-and-talk, we were given permission to search a home that had hundreds of marijuana plants. Not that unusual. But what was unusual was finding a book written by a prominent Seattle defense attorney, opened to a page on “Police Knock and Talks”, with a highlighted sentenced that stated something to the effect of ‘Say no to the police when asked for consent to search’. Even the attorney’s business card was used as a bookmark that had the same advice printed on the back of the card. Yet he willingly let us in.

This concept applies to all aspects of investigations, including technology related investigations like the Reality Winner case.

Part of the reason why the tried and true, traditional methods continue to work is that no matter how secure a criminal will try to be in all that he or she does, there are times where complacency creeps in. Add a bit of arrogance (“They’ll never catch me!”), and BAM. It’s over.

I’ve had cases where a dozen hard drives were wiped clean, but another dozen had plenty of evidence (illicit images). In these instances, the suspects were fanatical about wiping evidence until they weren’t. This applies to everything that anyone does with their electronic devices and online behavior. Complacency allows traditional methods to work and the complacency monster always wins because eventually everyone slacks off in something they do eventually.

Search warrants are not difficult to get

In a recent court decision, law enforcement is now required to obtain a search warrant for cell phone records. If you didn’t know how it worked before this decision came out…

http://www.governing.com/topics/public-justice-safety/tns-supreme-court-privacy.html

Depending on how you think this affects you personally, your perspective may be different. But in all practical reality, nothing really changed. Your cell phone records are not protected from reasonable search and seizure. The records are still there, and if probable causes exists, law enforcement can get it with a warrant. I do not believe any criminals are jumping for joy over this court decision, because they are still ripe to have their records pulled with search warrants.

As far as how difficult is it to get a search warrant…it’s not difficult at all if you have probable cause. I have found that the longest time to apply for a warrant is the time it takes to type up the affidavit. The faster you can type, the faster you can get a warrant. The rest of the process only takes minutes (not counting any traffic while driving to the judge’s home…). But you don’t even have to type up a warrant if you don’t have time. Simply call a judge, get sworn in over the phone, and ask the judge for a telephonic warrant with a verbal affidavit. I’ve done both ways and typically had a signed warrant in under an hour…nearly every single time. I've had warrants in less than 30 minutes on a few occasions. If a warrant is needed faster than 30 minutes, then you might be dipping into exigent circumstances, which is a different topic.

Your cell phone records probably weren’t going to be pulled anyway, and won’t be unless there is probable cause to do. As for criminals knowing that cops need a warrant now, that won’t make a bit of difference as to how they use cell phones to commit or facilitate crimes and it won’t make a difference in that law enforcement will still get 100% access to everything.

The point

No matter how sophisticated your suspect in (or custodian in a civil case), never forego looking for the low hanging fruit first. Don't assume that files were wiped, browsing was only done with Tor, or that the suspect didn't use his home Internet to hack into a victim's system. Because they do and always will. Old hat stuff works.

June 19, 2018

In the #DFIR world, it seems like everyone is an expert….

…because everyone can be an expert.

One thing about the DFIR field and all of its ever-encompassing related fields, is that it is physically impossible for any one person to be an expert in the entirety of the field. To even try to be ‘that DFIR expert’ is to set yourself up for failure.

One thing about the DFIR field and all of its ever-encompassing related fields, is that it is physically impossible for any one person to be an expert in the entirety of the field. To even try to be ‘that DFIR expert’ is to set yourself up for failure.

I base my opinion on what I’ve seen over the years, especially after the first time being court qualified as an expert. Once, I was even qualified as a “computer forensic expert”. It makes me cringe every time I think about that, because as far as I am concerned, no one can be realistically be an all-encompassing DFIR expert.

The reason I distance myself from being looked at as an expert is that the perception of what a court qualified expert means to many people is most time incorrect. Being an expert implies that you know everything, that you are smarter than anyone else in that area, and that your opinion is practically fact.

Reality is a bit different.

Without getting into the nitty gritty of expert witness testimony or how to become court qualified, let me talk about the one aspect of specialization. If you are in the field of DFIR, working to get into the field of DFIR, or preparing yourself to eventually get into the field of DFIR, you have a 100% chance of becoming an expert in a shorter period of time than you can imagine.

You can do this because you can focus on something in this field, something as little as a few bytes or as massive as some function of an operating system and learn everything about it. You can learn so much, that eventually you start discovering things about it that no one knows. You can be the expert of that thing that you researched. Do not take this lightly. If you are looking for something to propel you into DFIR, find something that no one is doing, cares about, or knows about. Research that thing and find the DFIR relationship of that thing. Master it. Publish it with any means possible, including a blog post.

I can see the future…

Here is what will happen if, I mean when, you do this. You will be recognized in the community as an expert. Court? You will shine as an expert. Confidence? Oh yeah, you will get some. Take that one thing you did and do it again with something else.

That’s all you need to do.

A warning…

Once you become noticed for something in DFIR, you are going to be known as an expert in DFIR, which means some will will think that you know everything. For example, I was having I was having a conversation with an awesome malware researcher, who has done amazing things in her career. She can tear apart malware as if it were packaged in a wet, paper bag. As for me, I can reverse malware too! However, I can’t do it as well, or as fast, or as complete as she can. Nowhere near it. It is not the best thing I that I can do. I actually have a 90-second conversation limit when talking about reversing malware, because after 90 seconds, all I hear is a foreign language that I do not know. (I have been increasing my 90 seconds of knowledge on a slow, but steady rate...).

The point in this story is that in this awesome conversation, after that 90 second mark, I am sure that my face turned blank and she realized that she was the expert in malware, not me. There is nothing wrong in not knowing something, and part of the expertise field is recognizing your limits, that others will know more than you do in one area of DFIR, and you will know more than they do in other areas. This is also makes a good team, when team members cover a broad range of expertise, spread out among the team.

So don’t be shy to say, “I have no idea what you are talking about” when you have no idea of what someone is talking about, because in this field, we each do different things, enjoy different aspects, focus on different specifics, and excel in different facets. That is how you can be an expert too. Focus on that one thing, and one thing at a time.

May 27, 2018

Why does Google think this is a good idea?

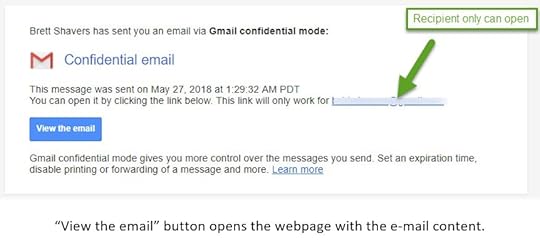

An incredible new Gmail feature, “Confidential E-mail Mode” by Google looks to be one of those wonderful surprises that will be catching people off guard in a bad way.

TL:DR version.

Send an email using Gmail in which Google puts a link in the body (and removes your e-mail content from the e-mail). The link, in which only the recipient can open, opens an external webpage where the e-mail content can be read. The e-mail can be read, but not forwarded, downloaded, copied, or printed. This is probably a bad idea.

Google needs to first define what “confidential” means as it applies to their Confidential Mode e-mail. In plain understanding, it should mean that only the intended recipients should be able to read the contents as it is private. In practice, the email is still on Google’s hard drives, most likely still indexed by Google, and ‘deleted’ only from the sender and receiver’s view, but not from Google.

As a point of privacy, Google Confidential E-mail is not private and average users could mistakenly believe the Google confidential E-mail is encrypted e-mail that no one can read. The good news is that if Google is not deleting the messages from its servers, they would be available with court orders in criminal investigations.

Only one of my Gmail accounts has the Confidential Mode option, and you can send a Google Confidential e-mail to any e-mail service besides Google and it will work the same: User clicks a link in the e-mail and prays that the e-mail is legitimate.

Perhaps the biggest issue will be the ease at which phishing campaigns will take on using a Confidential Gmail, where the user has no idea of the content or can judge maliciousness based on content. Users will now only have the sender and subject-line to determine if the e-mail is a phishing attempt. If the sender e-mail address is from a known sender that has been compromised or spoofed, then only the subject-line will be available for a clue as to the legitimacy of the e-mail.

Nothing should change related to host forensics, as webmail/Internet forensics is the same (same or more difficult depending on everything, such if the Tor browser was used).

The big change is yet another entry point through a potentially well-crafted phishing attempt using a Gmail feature. Users can’t see the content until they click the link to open the external webpage, which will be too late. Personally, I don’t see this taking off as a widely used feature since it involves adding a step to read an e-mail. One extra button will make it useless as it will be more frustrating when it consumes three more seconds to read every e-mail sent via Confidential e-mail. As for the Confidential e-mail not being able to print or forward, taking a photo with a smart phone quickly negates the security feature of deleting the e-mail all together (yes, I know the content may be gone, but the original e-mail metadata is still there with the original e-mail).

For the infosec folks. Maybe it is a good time to make sure users don't click links in e-mails. Hey…don’t we say that already anyway? Sheesh.

Thanks Google.

May 20, 2018

Don't become a hacker by hacking back a hacker that hacked you

Emotions run deep if you are victimized. Initially, you want blood at any cost. You also willingly accept any potential future regret, as long as you get blood today. And unfortunately, no matter how fast justice may come, it will not be soon enough. This rationale applies to being a victim of any crime and having your computer system hacked counts.

I’ll give a quick two cents in this post just as I did to a victim-client that was hacked. "Don’t hack back." Stop talking about and stop thinking about it. To be clearer, make sure everyone in your company understands not to hack back. Better to focus on plugging the holes and implement your response plan.

Here are some bullet points I give to clients who are blinded by revenge and want blood:

You might spend more money than you have in a vain attempt to ID the attacker

You might hack an innocent party

You might hack a nation-state

You might be hacked back by the “innocent” party you hacked back (eg: a nation-state or a better hacker than you would be)

You might become a criminal hacker

There are more reasons, but I believe these pretty much cover it. Going broke, victimizing an innocent party, and going to jail are strong motivators to counter the emotion to exact revenge on a hack.