Greg Mitchell's Blog, page 4

June 5, 2016

Irises

Published on June 05, 2016 18:31

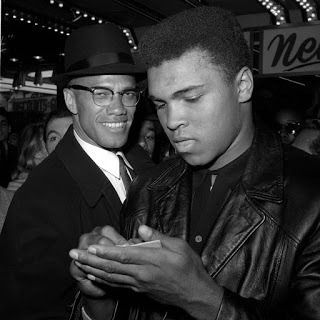

Leonard on Ali

Have been too busy--and on a much-needed vacation--this weekend to post about the passing the Muhammad Ali, one of my two greatest heroes of the 1960s (along with Dylan) who helped shape part of my life, cultural and political. I did post on Facebook the famous photo of the two of them backstage at Madison Square Garden in 1975 (a concert I attended) and the video of Ali singing with another one of my idols, Sam Cooke. I didn't expect to find anything about Leonard Cohen and Ali but just now Leonard's biographer Sylvie Simmons posted this on Facebook:

Have been too busy--and on a much-needed vacation--this weekend to post about the passing the Muhammad Ali, one of my two greatest heroes of the 1960s (along with Dylan) who helped shape part of my life, cultural and political. I did post on Facebook the famous photo of the two of them backstage at Madison Square Garden in 1975 (a concert I attended) and the video of Ali singing with another one of my idols, Sam Cooke. I didn't expect to find anything about Leonard Cohen and Ali but just now Leonard's biographer Sylvie Simmons posted this on Facebook:**

One time, it must have been 15 years ago, MOJO magazine was running one of those round-up pieces where we asked our musician heros to name their heroes. I called Leonard Cohen and asked him who his hero was."I don't know it's the designation 'hero' that I have difficulty with, because that implies some kind of reverence that is somewhat alien to my nature", he sad, and went on to name a whole lot of people he had "love and affection" for, from Roshi to Ramesh Balsekar, Lorca to Yeats.

And then the next morning he sent me an email. This is what it said:

i forgot

my hero is mohammed ali

as they say about the Timex in their ads

takes a lickin'

keeps on tickin'

Of course Muhammad Ali would be his hero. Though born worlds apart, there was a lot in common. Ali was a wise man, a fighter and poet. He worked harder than anyone and was generous with his money. He had dignity, courage and humour and stood up for what he believed.

Leonard's son Adam Cohen appears to have inherited Ali as his own hero, naming his son after him.

I've been reading so many fine words on Ali this weekend by people who knew him far better than I.

All I can add is that America has lost one of its greatest.

Published on June 05, 2016 17:34

May 26, 2016

Special Feature Marking Obama's Visit to Hiroshima

Since 1982, when I became the editor of Nuclear Times, I have perhaps written more words about the atomic bombings of 1945, and their aftermath for decades since, than anyone: in articles, in blog posts, in three books. Spending a month in the two atomic cities was, of course, something of a formative experience. A very small sampling of my writing on this subject sits below in this blog. And here is a separate page at Pressing Issues that traces what I call the "atomic cover-up" of images since 1945.

Published on May 26, 2016 06:51

May 22, 2016

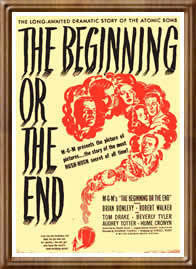

My Book: "Hollywood Bomb"

This is a disturbing--if rollicking--tale that I've written about in brief but finally got to explore at length, and it's published in e-book form: Hollywood Bomb: Harry S. Truman and the Unmaking of 'The Most Important' Movie Ever Made (Sinclair Books). That's a poster for the 1947 MGM film at left, and you'll find the trailer below. It's my 15th book, if you're keeping score at home, and can be read on iPads, Kindles, and so on, for just $2.99.

This is a disturbing--if rollicking--tale that I've written about in brief but finally got to explore at length, and it's published in e-book form: Hollywood Bomb: Harry S. Truman and the Unmaking of 'The Most Important' Movie Ever Made (Sinclair Books). That's a poster for the 1947 MGM film at left, and you'll find the trailer below. It's my 15th book, if you're keeping score at home, and can be read on iPads, Kindles, and so on, for just $2.99.A film titled The Beginning or the End was to be, in the words of MGM studio boss Louis B. Mayer, "the most important" movie ever made. But that was before it was distorted, even censored, with President Truman playing a key role. Continuing the book blurb:

Hollywood Bomb traces the wild, and largely untold, episode from its start, just hours after the first atomic device was exploded over Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1945. MGM was already trying to sew up exclusive rights to make the first celluloid epic about The Bomb. A rival studio raced to catch up with a script written by...Ayn Rand.

Who provided the key source for MGM in early September 1945? Young actress Donna Reed, whose high school science teacher had worked on the bomb project at Oak Ridge and now wanted to warn the world about its dangers.

It seemed, for a time, that the big-budget MGM film would serve as a warning to mankind about the dangers of going too far down the nuclear path, with the potential to rally public opinion against The Bomb before it was too late to halt an arms race that would eventually bring 50,000 nuclear warheads into the world. It even questioned Truman's decision to drop the bomb.

But that was before the making, and unmaking, of The Beginning or the End ended that chance, thanks in large part to intervention by the U.S. military and President Truman. At the White House, Truman even edited several versions of the script, deleting parts of his dialogue and adding distortions to buoy his decision to drop the bomb. And, in what must have been a first for Hollywood, actors slated to play two presidents in the same movie were fired after protests—from a former First Lady (Eleanor Roosevelt) and from the sitting President (Truman). My piece at The Nation elaborates.

Also intimately involved in this lively, often amazing tale, was a colorful cast of supporting players, including (besides Ayn Rand): Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, producer Hal Wallis, actors Donna Reed, Hume Cronyn and Brian Donlevy, Walter Lippmann, and Cardinal Spellman, among others. Once again, here's the link to Amazon.

My two previous books on this general subject were Hiroshima in America (with Robert Jay Lifton) and Atomic Cover-up . Here's the trailer. A fake and dopey "Inquiring Reporter" format.

Published on May 22, 2016 05:30

May 20, 2016

Why Hiroshima Narrative Still Matters: Americans Still Liable to Back Use Again

I've been writing about atomic/nuclear weapons and the first (and only) use of The Bomb in 1945 against civilians in war for almost 35 years now: literally hundreds of articles (from TV Guide to The New York Times) and two books, Hiroshima in America--with Robert Jay Lifton--and Atomic Cover-up. See the posts just below for my latest just last week after the announcement of President Obama's upcoming visit to Hiroshima. That's my photo at left in Hiroshima on August 6, 1984.

I've been writing about atomic/nuclear weapons and the first (and only) use of The Bomb in 1945 against civilians in war for almost 35 years now: literally hundreds of articles (from TV Guide to The New York Times) and two books, Hiroshima in America--with Robert Jay Lifton--and Atomic Cover-up. See the posts just below for my latest just last week after the announcement of President Obama's upcoming visit to Hiroshima. That's my photo at left in Hiroshima on August 6, 1984.I've covered a lot of ground, but part of the writing has focused on the case against dropping the two bombs, which killed over 200,000, the vast majority women and children. Occasionally some has asked, "Okay, fine, but what does it matter today?" I will reply: Polls show that most Americans, and media commentators, still support the use of the bomb in 1945 (historians are divided), and most American officials and all presidents have agreed. So the lesson is: the weapon can be used--even though most say "never again"--despite the promise of killing hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of civilians, and therefore it's more likely it will be used again. A line against using the bomb has been drawn...in the sand.

So, here's a new piece, and poll, at the Wall Street Journal. Offered a scenario today similar in some ways to the one in 1945--the U.S. is at war with Iran and faces a possible invasion of that country which might be forestalled if we drop a bomb on an Iranian city--six out of ten support the use of The Bomb. That figure rises to 8 in 10 among Republicans--so, BernieorBust people who seem have little fear of Donald Trump's finger on the nuclear button, take notice.

Now, I have to wonder about the sample for this survey. Oddly, only about 1 in 3 say our use against Japan in 1945 was justified. That is easily the lowest number I have ever seen in such poll. But maybe that is even scarier--for these same people then turned around and supported use against Iran. Think about it. The article also cites a 2013 survey that found 19% back using nukes against al-Qaeda even if conventional bombing, they were told, would be just as effective.

Published on May 20, 2016 06:33

May 18, 2016

New Public Editor and Iraq

UPDATE: This is my piece from two years ago, moving it up at my blog because Liz Spayd has just been named new Public Editor at The New York Times to succeed the terrific Margaret Sullivan (who is going to the Post). Frankly, I have not followed Spayd's work at CJR and cannot comment on that one way or the other.

UPDATE: This is my piece from two years ago, moving it up at my blog because Liz Spayd has just been named new Public Editor at The New York Times to succeed the terrific Margaret Sullivan (who is going to the Post). Frankly, I have not followed Spayd's work at CJR and cannot comment on that one way or the other. Unlike a lot of media and political writers I am not one to let bygones be bygones, at least in a very few tragic or high stakes cases. For example, the media failures in the run-up to the Iraq war, given the consequences. This explains my reaction to the Columbia Journalism Review today announcing, after a widely-watched search, that it was hiring Liz Spayd of The Washington Post as its new editor.

Now, I suppose I should review her entire career, for context, though others are doing it and you can read about it in plenty of places. She has been managing editor of the Post for years now and obviously supervised a good deal of important work (and some not so terrific, of course). But I am moved to recall, and then let go, one famous 2004 article, by Howard Kurtz, then media writer at the Post, which I covered at the time (when I was the editor of Editor & Publisher) and in my book on those media failures and Iraq, So Wrong for So Long .

In a nutshell: The NYT, under Bill Keller, had printed as an editors' note a very brief and very limited semi-apology for its horrific coverage during the run-up to the war. The Post, almost equally guilty (see headline in photo), didn't even do that, leaving it to one of its reporters, i.e. Kurtz, to report it out. His piece made the paper look pretty bad, with some embarrassing quotes from editor Len Downie, Bob Woodward and Karen DeYoung, among others. And there was this passage about Spayd:

Liz Spayd, the assistant managing editor for national news, says The Post's overall record was strong.In some ways, the "hero" of the Kurtz piece was Walter Pincus, the longtime national security who had tried to get more skeptical stories on Iraq WMD in the paper (or get them on the front-page).

"I believe we pushed as hard or harder than anyone to question the administration's assertions on all kinds of subjects related to the war. . . . Do I wish we would have had more and pushed harder and deeper into questions of whether they possessed weapons of mass destruction? Absolutely," she said. "Do I feel we owe our readers an apology? I don't think so."

But while Pincus was ferreting out information "from sources I've used for years," some in the Post newsroom were questioning his work. Editors complained that he was "cryptic," as one put it, and that his hard-to-follow stories had to be heavily rewritten.Michael Getler later reviewed his years as ombudsman at the Post from 2000 to 2005, and offered a strong critique of the role of the paper's editors in the Iraq WMD disaster. He observed:

Spayd declined to discuss Pincus's writing but said that "stories on intelligence are always difficult to edit and parse and to ensure their accuracy and get into the paper."

I should say at this point the Post is an excellent paper, and it also did some excellent reporting before the war—more than you might think. But I also had a catbird seat watching it stumble and, while my observations are necessarily about the Post, they may be more broadly applicable. From where I sat, there were two newsroom failures, in particular, at the root of what went wrong with pre-war reporting. One was a failure to pay enough attention to events that unfolded in public, rather than just the exclusive stuff that all major newspapers like to develop. The other was a failure of editors and editing up and down the line that resulted in a focus on getting ready for a war that was coming rather than the obligation to put the alternative case in front of readers in a prominent way. This resulted in far too many stories, including some very important ones, being either missed, underplayed, or buried.Gelter chronicles the many important stories the Post either did not cover or buried deep inside the paper (including reports on large antiwar marches). Then he adds:

Here’s a brief sampling of additional Post headlines that, rather stunningly, failed to make the front of the newspaper: “Observers: Evidence for War Lacking,” “U.N. Finds No Proof of Nuclear Program,” “Bin Laden-Hussein Link Hazy,” “U.S. Lacks Specifics on Banned Arms,” “Legality of War Is a Matter of Debate,” and “Bush Clings to Dubious Allegations About Iraq.” In short, it wasn’t the case that important, challenging reporting wasn’t done. It just wasn’t highlighted.Of course, Liz Spayd was just one of a group of editors and hardly deserves full blame for the Post's performance. But she did defend that record afterward--and said no apology was needed.

Published on May 18, 2016 10:31

May 10, 2016

What Obama Must Visit: Inside a Mound in Hiroshima

In the northwestern corner of the Hiroshima Peace Park, amid a quiet grove of trees, the earth suddenly swells. It is not much of a mound -- only about ten feet high and sixty feet across. Unlike most mounds, however, this one is hollow, and within it rests perhaps the greatest concentration of human residue in the world.

Grey clouds rising from sticks of incense hang in the air, spookily. Tourists do not dawdle here. Visitors searching for the Peace Bell, directly ahead, or the Children's Monument, down the path to the right, hurry past it without so much as a sideways glance. Still, it has a strange beauty: a lump of earth (not quite lush) topped by a small monument that resembles the tip of a pagoda.

Grey clouds rising from sticks of incense hang in the air, spookily. Tourists do not dawdle here. Visitors searching for the Peace Bell, directly ahead, or the Children's Monument, down the path to the right, hurry past it without so much as a sideways glance. Still, it has a strange beauty: a lump of earth (not quite lush) topped by a small monument that resembles the tip of a pagoda.

On one side of the Memorial Mound the gray wooden fence has a gate, and down five steps from the gate is a door. Visitors are usually not allowed through that door, but occasionally the city of Hiroshima honors a request from a foreign journalist.

Inside the mound the ceiling is low, the light fluorescent. One has to stoop to stand. To the right and left, pine shelving lines the walls. Stacked neatly on the shelves, like cans of soup in a supermarket, are white porcelain canisters with Japanese lettering on the front. On the day I visited, there were more than a thousand cans in all, explained Masami Ohara, a city official. Each canister contained the ashes of one person killed by the atomic bomb.

Behind twin curtains on either side of an altar, several dozen pine boxes, the size of caskets, were stacked, unceremoniously, from floor to ceiling. They hold the ashes of about 70,000 unidentified victims of the bomb. If, in an instant, all of the residents of Wilmington, Delaware, or Santa Fe, New Mexico, were reduced to ashes, and those ashes carried away to one repository, this is all the room the remains would require.

More than 100,000 in Hiroshima were killed by The Bomb, the vast majority of them women and children, plus elderly males. Fewer than one in ten were in the military.

Most of those who died in Hiroshima were cremated quickly, partly to prevent an epidemic of disease. Others were efficiently turned to ash by the atomic bomb itself, death and cremation occurring in the same instant. Those reduced by human hands were cremated on makeshift altars at a temple that once stood at the present site of the mound, one-half mile from the hypocenter of the atomic blast.

In 1946, an Army Air Force squad, ordered by Gen. Douglas MacArthur to film the results of the massive U.S. aerial bombardment of Japanese cities during World War II, shot a solemn ceremony at the temple, capturing a young woman receiving a canister of ashes from a local official. That footage, and all of the rest that they filmed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealing the full aftermath of the bombings, would be suppressed by the United States for decades (as I probe in my book Atomic Cover-Up ).

Later that year, survivors of the atomic bombing began contributing funds to build a permanent vault at this site and, in 1955, the Memorial Mound was completed. For several years the collection of ashes grew because remains of victims were still being found. One especially poignant pile was discovered at an elementary school.

The white cans (that's my photo) on the shelves have stood here for decades, unclaimed by family members or friends. In many cases, all of the victims' relatives and friends were killed by the bomb. Every year local newspapers publish the list of names written on the cans, and every year several canisters are finally claimed and transferred to family burial sites. Most of the unclaimed cans (a total of just over 800 in 2010, for example) will remain in the mound in perpetuity, now that so many years have passed.

The white cans (that's my photo) on the shelves have stood here for decades, unclaimed by family members or friends. In many cases, all of the victims' relatives and friends were killed by the bomb. Every year local newspapers publish the list of names written on the cans, and every year several canisters are finally claimed and transferred to family burial sites. Most of the unclaimed cans (a total of just over 800 in 2010, for example) will remain in the mound in perpetuity, now that so many years have passed.

They are a chilling sight. The cans are bright white, like the flash in the sky over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945. From all corners of the city the ashes were collected: the remains of soldiers, physicians, housewives, infants. Unclaimed, they at least have the dignity of a private urn, an identity, a life (if one were able to look into it) before death.

But what of the seventy thousand behind the curtains? The pine crates are marked with names of sites where the human dust and bits of bone were found -- a factory or a school, perhaps, or a neighborhood crematory. But beyond that, the ashes are anonymous. Thousands may still grieve for these victims but there is no dignity here. "They are all mixed together," said Ohara, "and will never be separated or identified." Under a mound, behind two curtains, inside a few pine boxes: This is what became of one-quarter of the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Grey clouds rising from sticks of incense hang in the air, spookily. Tourists do not dawdle here. Visitors searching for the Peace Bell, directly ahead, or the Children's Monument, down the path to the right, hurry past it without so much as a sideways glance. Still, it has a strange beauty: a lump of earth (not quite lush) topped by a small monument that resembles the tip of a pagoda.

Grey clouds rising from sticks of incense hang in the air, spookily. Tourists do not dawdle here. Visitors searching for the Peace Bell, directly ahead, or the Children's Monument, down the path to the right, hurry past it without so much as a sideways glance. Still, it has a strange beauty: a lump of earth (not quite lush) topped by a small monument that resembles the tip of a pagoda.On one side of the Memorial Mound the gray wooden fence has a gate, and down five steps from the gate is a door. Visitors are usually not allowed through that door, but occasionally the city of Hiroshima honors a request from a foreign journalist.

Inside the mound the ceiling is low, the light fluorescent. One has to stoop to stand. To the right and left, pine shelving lines the walls. Stacked neatly on the shelves, like cans of soup in a supermarket, are white porcelain canisters with Japanese lettering on the front. On the day I visited, there were more than a thousand cans in all, explained Masami Ohara, a city official. Each canister contained the ashes of one person killed by the atomic bomb.

Behind twin curtains on either side of an altar, several dozen pine boxes, the size of caskets, were stacked, unceremoniously, from floor to ceiling. They hold the ashes of about 70,000 unidentified victims of the bomb. If, in an instant, all of the residents of Wilmington, Delaware, or Santa Fe, New Mexico, were reduced to ashes, and those ashes carried away to one repository, this is all the room the remains would require.

More than 100,000 in Hiroshima were killed by The Bomb, the vast majority of them women and children, plus elderly males. Fewer than one in ten were in the military.

Most of those who died in Hiroshima were cremated quickly, partly to prevent an epidemic of disease. Others were efficiently turned to ash by the atomic bomb itself, death and cremation occurring in the same instant. Those reduced by human hands were cremated on makeshift altars at a temple that once stood at the present site of the mound, one-half mile from the hypocenter of the atomic blast.

In 1946, an Army Air Force squad, ordered by Gen. Douglas MacArthur to film the results of the massive U.S. aerial bombardment of Japanese cities during World War II, shot a solemn ceremony at the temple, capturing a young woman receiving a canister of ashes from a local official. That footage, and all of the rest that they filmed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealing the full aftermath of the bombings, would be suppressed by the United States for decades (as I probe in my book Atomic Cover-Up ).

Later that year, survivors of the atomic bombing began contributing funds to build a permanent vault at this site and, in 1955, the Memorial Mound was completed. For several years the collection of ashes grew because remains of victims were still being found. One especially poignant pile was discovered at an elementary school.

The white cans (that's my photo) on the shelves have stood here for decades, unclaimed by family members or friends. In many cases, all of the victims' relatives and friends were killed by the bomb. Every year local newspapers publish the list of names written on the cans, and every year several canisters are finally claimed and transferred to family burial sites. Most of the unclaimed cans (a total of just over 800 in 2010, for example) will remain in the mound in perpetuity, now that so many years have passed.

The white cans (that's my photo) on the shelves have stood here for decades, unclaimed by family members or friends. In many cases, all of the victims' relatives and friends were killed by the bomb. Every year local newspapers publish the list of names written on the cans, and every year several canisters are finally claimed and transferred to family burial sites. Most of the unclaimed cans (a total of just over 800 in 2010, for example) will remain in the mound in perpetuity, now that so many years have passed.They are a chilling sight. The cans are bright white, like the flash in the sky over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945. From all corners of the city the ashes were collected: the remains of soldiers, physicians, housewives, infants. Unclaimed, they at least have the dignity of a private urn, an identity, a life (if one were able to look into it) before death.

But what of the seventy thousand behind the curtains? The pine crates are marked with names of sites where the human dust and bits of bone were found -- a factory or a school, perhaps, or a neighborhood crematory. But beyond that, the ashes are anonymous. Thousands may still grieve for these victims but there is no dignity here. "They are all mixed together," said Ohara, "and will never be separated or identified." Under a mound, behind two curtains, inside a few pine boxes: This is what became of one-quarter of the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Published on May 10, 2016 22:00

As Obama Agrees to Go Hiroshima: A Protest Letter for Another President

Earlier I published an excerpt from my new book,

Hollywood Bomb: The Unmaking of 'The Most Important' Movie Ever Made

, on Ayn Rand writing a rival pro-nuclear script for a rival studio. Here's another excerpt, about what happened after President Truman objected to a scene in the MGM film on The Bomb, and ordered revisions.

A bizarre, and revealing, postscript to President Truman's involvement with The Beginning or the End was provided by Roman Bohnen, the actor who portrayed Truman in the original sequences. Bohnen, a 51-year-old character actor, had appeared in such well-known movies as Of Mice and Men, The Song of Bernadette, and A Bell for Adano.

A bizarre, and revealing, postscript to President Truman's involvement with The Beginning or the End was provided by Roman Bohnen, the actor who portrayed Truman in the original sequences. Bohnen, a 51-year-old character actor, had appeared in such well-known movies as Of Mice and Men, The Song of Bernadette, and A Bell for Adano.

Learning of the need for a re-take, following the White House critiques, Bohnen on December 2, 1946, wrote the President a polite, but slyly critical letter. He noted the President's concerns about the depiction of his decision to “send the atom bomb thundering into this troubled world,” adding that he could "well imagine the emotional torture you must have experienced in giving that fateful order, torture not only then, but now—perhaps even more so." So he could “understand your wish that the scene be re-filmed in order to do fuller justice to your anguished deliberation in that historic moment.”

Then he offered a suggestion. People would be talking about his decision for a hundred years, he observed, "and posterity is quite apt to be a little rough" on Truman "for not having ordered that very first atomic bomb to be dropped outside of Hiroshima [his emphasis]with other bombs poised to follow, but praise God never to be used."

His suggestion: Truman should play himself in the film! If he believed in his decision so strongly why not re-enact it himself?

"If I were in your difficult position," Bohnen wrote, "I would insist on so doing. Unprecedented, yes--but so is the entire circumstance, including the unholy power of that monopoly weapon." Perhaps to show that he was serious about all this, Bohnen indicated that he was sending a copy of the letter to Louis B. Mayer.

Ten days later, Truman responded warmly, apparently missing (or ignoring) Bohnen's sarcasm. He thanked the actor for his suggestion that he play himself but admitted that he didn't have "the talent to be a movie star" and expressed confidence that Bohnen would do him justice. Truman then took time to defend in some detail the decision to use the bomb, revealing much more about his emotional attitude than he usually did.

The President explained that what he had objected to in the film was that it pictured his decision as a "snap judgment," while in reality "it was anything but that." After the weapon was tested, and the Japanese given "ample warning," the bomb was used against two cities "devoted almost exclusively to the manufacturer of ammunition and weapons of destruction." (A complete lie.)

“I have no qualms about it whatever for the simple reason that it was believed the dropping of not more than two of these bombs would bring the war to a close. The Japanese in their conduct of the war had been vicious and cruel savages and I came to the conclusion that if two hundred and fifty thousand young Americans could be saved from slaughter the bomb should be dropped, and it was.

"As I said before," Truman concluded, "the only objection to the film was that I was made to appear as if no consideration had been given to the effects of the result of dropping the bomb—that is an absolutely wrong impression." There is nothing on the historical record, or in Truman’s letters and diaries, however, to indicate that he did give strong consideration to the human toll in the Japanese cities, the release of radiation--or letting the nuclear genie out of the bottle.

For whatever reason, MGM replaced Bohnen in the re-takes with a slightly younger actor, who was instructed to portray Truman with more of a "military bearing" (a revealing suggestion in itself). Did Truman or someone at the White House demand that Bohnen be replaced after reading his note to Truman? (This seems likely.) Did Louis B. Mayer drop him after seeing a copy of the letter sent to him by Bohnen? Or did a conflicted Bohnen simply quit?

In any event, when The Beginning or the End was finally readied for release, the actor playing the President in the pivotal scene was Art Baker, who portrays the peppy, salt-of-the-earth Truman as magisterial and aristocratic: in other words, as a worthy successor to Franklin Roosevelt. Baker wrote to Charlie Ross on January 7, 1947, revealing that he’d been picked to play the president in the re-take—and then expressing warm feelings for Truman.

For much more, see Hollywood Bomb.

A bizarre, and revealing, postscript to President Truman's involvement with The Beginning or the End was provided by Roman Bohnen, the actor who portrayed Truman in the original sequences. Bohnen, a 51-year-old character actor, had appeared in such well-known movies as Of Mice and Men, The Song of Bernadette, and A Bell for Adano.

A bizarre, and revealing, postscript to President Truman's involvement with The Beginning or the End was provided by Roman Bohnen, the actor who portrayed Truman in the original sequences. Bohnen, a 51-year-old character actor, had appeared in such well-known movies as Of Mice and Men, The Song of Bernadette, and A Bell for Adano.Learning of the need for a re-take, following the White House critiques, Bohnen on December 2, 1946, wrote the President a polite, but slyly critical letter. He noted the President's concerns about the depiction of his decision to “send the atom bomb thundering into this troubled world,” adding that he could "well imagine the emotional torture you must have experienced in giving that fateful order, torture not only then, but now—perhaps even more so." So he could “understand your wish that the scene be re-filmed in order to do fuller justice to your anguished deliberation in that historic moment.”

Then he offered a suggestion. People would be talking about his decision for a hundred years, he observed, "and posterity is quite apt to be a little rough" on Truman "for not having ordered that very first atomic bomb to be dropped outside of Hiroshima [his emphasis]with other bombs poised to follow, but praise God never to be used."

His suggestion: Truman should play himself in the film! If he believed in his decision so strongly why not re-enact it himself?

"If I were in your difficult position," Bohnen wrote, "I would insist on so doing. Unprecedented, yes--but so is the entire circumstance, including the unholy power of that monopoly weapon." Perhaps to show that he was serious about all this, Bohnen indicated that he was sending a copy of the letter to Louis B. Mayer.

Ten days later, Truman responded warmly, apparently missing (or ignoring) Bohnen's sarcasm. He thanked the actor for his suggestion that he play himself but admitted that he didn't have "the talent to be a movie star" and expressed confidence that Bohnen would do him justice. Truman then took time to defend in some detail the decision to use the bomb, revealing much more about his emotional attitude than he usually did.

The President explained that what he had objected to in the film was that it pictured his decision as a "snap judgment," while in reality "it was anything but that." After the weapon was tested, and the Japanese given "ample warning," the bomb was used against two cities "devoted almost exclusively to the manufacturer of ammunition and weapons of destruction." (A complete lie.)

“I have no qualms about it whatever for the simple reason that it was believed the dropping of not more than two of these bombs would bring the war to a close. The Japanese in their conduct of the war had been vicious and cruel savages and I came to the conclusion that if two hundred and fifty thousand young Americans could be saved from slaughter the bomb should be dropped, and it was.

"As I said before," Truman concluded, "the only objection to the film was that I was made to appear as if no consideration had been given to the effects of the result of dropping the bomb—that is an absolutely wrong impression." There is nothing on the historical record, or in Truman’s letters and diaries, however, to indicate that he did give strong consideration to the human toll in the Japanese cities, the release of radiation--or letting the nuclear genie out of the bottle.

For whatever reason, MGM replaced Bohnen in the re-takes with a slightly younger actor, who was instructed to portray Truman with more of a "military bearing" (a revealing suggestion in itself). Did Truman or someone at the White House demand that Bohnen be replaced after reading his note to Truman? (This seems likely.) Did Louis B. Mayer drop him after seeing a copy of the letter sent to him by Bohnen? Or did a conflicted Bohnen simply quit?

In any event, when The Beginning or the End was finally readied for release, the actor playing the President in the pivotal scene was Art Baker, who portrays the peppy, salt-of-the-earth Truman as magisterial and aristocratic: in other words, as a worthy successor to Franklin Roosevelt. Baker wrote to Charlie Ross on January 7, 1947, revealing that he’d been picked to play the president in the re-take—and then expressing warm feelings for Truman.

For much more, see Hollywood Bomb.

Published on May 10, 2016 06:55

True Nature of Trump Supporters

If you've heard it once, you've heard it a thousand times from the mainstream media: Most of Donald Trump's supporters are not fringe people, they are just angry, disaffected workers afraid for their jobs and standard of living and blah blah blah. This is said despite what polls have consistently shown about the beliefs of the majority of them. Now a new PPP poll finds that 65% of those with a favorable view of Trump believe that Clinton is a Muslim and only 13% feel he is Christian. And:

59% think President Obama was not born in the United States, only 23% think that he was --27% think vaccines cause autism, 45% don't think they do, another 29% are not sure. --24% think Antonin Scalia was murdered, just 42% think he died naturally, another 34% are unsure.The polls also finds Trump narrowing gap on Hillary's lead.

Published on May 10, 2016 06:11

Obama Breaks Mold, to Visit Hiroshima

Update, May 10, 2016: President Obama announced today that he will become first president to visit Hiroshima while in office but will not apologize for U.S. using the bomb (nor has Hiroshima demanded this, even if warranted).

Update, May 10, 2016: President Obama announced today that he will become first president to visit Hiroshima while in office but will not apologize for U.S. using the bomb (nor has Hiroshima demanded this, even if warranted).Secretary of State John Kerry toured the Hiroshima memorial sites last month and said: .

“It is a stunning display. It is a gut-wrenching display, It tugs at all of your sensibilities as a human being. It reminds everybody of the extraordinary complexity of choices in war and of what war does to people, to communities, to countries, to the world.”

UPDATE 2015: Caroline, yes: she is back.

UPDATE 2014: Caroline Kennedy, the new ambassador, did attend the memorial service in both cities. Photo left as she lay wreath in Nagasaki today.

UPDATE 2013: Caroline Kennedy sworn in as new U.S. ambassador--and if the new tradition holds, she will represent America at the Hiroshima and Nagasaki memorial services next August. Here father never got there, but she will.

Earlier: Sensitive to world opinion about the use of atomic weapons against Japan in 1945, no American president has ever visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki while in office. Except for Dwight D. Eisenhower, the former general, none of them has expressed any misgivings about the use of the bombs in 1945. Shortly after becoming president, however, Barack Obama took the surprising step of at least expressing a desire to go to the two cities.

Then, in 2011, for the first time, a US ambassador to Japan, John Roos, attended the annual August 6 commemoration in Hiroshima. And in 2011, for the first time ever, the United States sent an official representative to the annual memorial service in Nagasaki—the deputy chief of mission at the US Embassy in Tokyo, James P. Zumwalt. He read a statement from Obama expressing hope to work with Japan for a world without nuclear weapons, a goal the president expressed early in his term but has made little progress on achieving. “I was deeply moved,” Zumwalt told reporters after attending the ceremony. “Japan and the United States have the common vision for a world free of nuclear weapons, so it is important that the two countries make efforts to realize it.”

Naturally, many conservatives accused Obama of "apologizing" for Truman dropping the bomb.

This year, Roos will again attend the Hiroshima memorial--meaning this has truly become a new tradition, at least under this president. Next year, it appears, Caroline Kennedy will do the honors, with her special link to a former president.

While many Japanese hail the US moves, some of the survivors of the bombing and their ancestors are skeptical. Katsumi Matsuo, who lost her mother in the attack, told the Mainichi Shimbun in 2011, “What is the point in him coming now, after 66 years? His visit will only be meaningful if it promotes a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Still, Obama has broken a sad record of total denial, which has accompanied the suppression of key evidence about the effects of the bombings (as chronicled in my new book and e-book Atomic Cover-up) dating back to the 1940s.

Of course, there was no way President Truman was going to make that visit, even telling an aide, after leaving the White House, that while he might meet with survivors of the bombing in the United States, he would “not kiss their asses.” President Eisenhower did not visit the atomic cities, but he famously expressed displeasure with the use of the bombs in 1945, saying we shouldn’t have hit Japan “with that awful thing.” Richard Nixon came to Hiroshima before becoming president.

Reflecting on the visit in a 1985 interview with Roger Rosenblatt, he said the bombings saved lives, but noted that General Douglas MacArthur had told him it was a “tragedy” that the weapon was used against “noncombatants.”

Jimmy Carter visited Hiroshima after leaving office but did not take part in any ceremony or comment afterward. Ronald Reagan also invoked the notion that the bombings actually saved lives. When protests from conservatives and some veterans groups caused first the censorship, then shutdown, of a full exploration of the atomic bombings at the Air & Space Museum in Washington, DC, in 1995, President Clinton backed the suppression.

So two cheers for Obama for at least marking what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Next step: an honest American reappraisal of the bombings and real progress on nuclear abolition.

Note: Last year, President Harry S Truman’s grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, became the first kin of the president (son of his daughter) to step foot in one of the two cities he ordered destroyed in August 1945, killing over 200,000, the vast majority civilians. Four days before the annual commemoration, he toured the city and exhibits in the Peace Museum and met with survivors who seemed pleased, while pointing out they still held his granddad in low esteem.

Then on the morning of August 6--late on August 5 in the U.S.--he took part in the annual official ceremony in Hiroshima's Peace Park (which I attended back in1984). He told journalists that it was hard to listen to the tragic stories of the survivors but he was glad he did it to gain a wider appreciation of the effects (and in some cases, after-effects) of his grandfather's action. Japanese leaders made their annual pleas for antinuclear policies, with growing emphasis on the nuclear power aspects after the Fukushima disaster.

Daniel said he did not second-guess Truman’s decision, offering the usual bromides about no-good-decisions in war. He should be congratulated for at least making the trip, but his name might he Denial, not Daniel. Some no-good decisions are worse than others.

Published on May 10, 2016 05:30