Greg Mitchell's Blog, page 228

August 13, 2013

Poitras Profiled

Full piece by Peter Maass from this coming Sunday's NYT Magazine on the well-known filmmaker Laura Poitras and role in the Edward Snowden affair. Bonus: photo of Glenn Greenwald at home with dogs.

Amid the chaos, Poitras, an intense-looking woman of 49, sat in a spare bedroom or at the table in the living room, working in concentrated silence in front of her multiple computers. Once in a while she would walk over to the porch to talk with Greenwald about the article he was working on, or he would sometimes stop what he was doing to look at the latest version of a new video she was editing about Snowden. They would talk intensely — Greenwald far louder and more rapid-fire than Poitras — and occasionally break out laughing at some shared joke or absurd memory. The Snowden story, they both said, was a battle they were waging together, a fight against powers of surveillance that they both believe are a threat to fundamental American liberties.See separate, once-encrytped, Q & A interview with Snowden.

Published on August 13, 2013 06:51

August 12, 2013

Another Travel Day

Sorry for lighter posting the past days, been away and/or traveling. Back to "normal" by this evening, god help ya.

Published on August 12, 2013 05:10

August 11, 2013

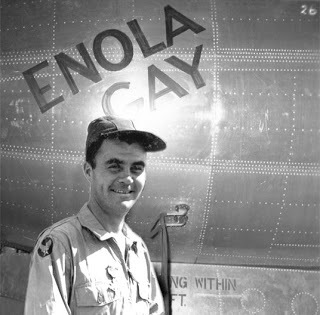

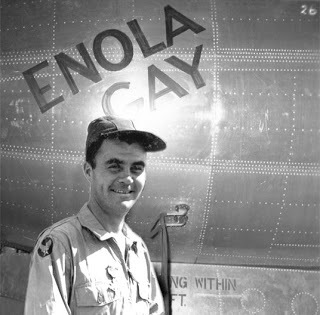

Hiroshima Pilot Didn't Lose Any Sleep Over It

Paul W. Tibbets, pilot of the plane, the "Enola Gay" (named for his mother), which dropped the atomic bomb over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. died at 92 in 2007, defending the bombing to the end of his life. Some of the obits noted that he had requested no funeral or headstone for his grave, not wishing to create an opportunity for protestors to gather.

I had a chance to interview Tibbets nearly 30 years ago, and wrote about it for several newspapers and magazines and in the book I wrote, Atomic Cover-up . Later I got to meet and sit next to the pilot who dropped the bomb over Nagasaki, Charles Sweeney, on Larry King's CNN show. I wonder how many other writers have met both of them (and also journeyed to the two atomic cities and met dozens of survivors).

The hook for the Tibbets interview was this: While spending a month in Japan on a grant in 1984, I met a man named Akihiro Takahashi. He was one of the many child victims of the atomic attack, but unlike most of them, he survived (though with horrific burns and other injuries), and grew up to become a director of the memorial museum in Hiroshima.

Takahashi showed me personal letters to and from Tibbets, which had led to a remarkable meeting between the two elderly men in Washington, D.C. At that recent meeting, Takahashi expressed forgiveness, admitted Japan's aggression and cruelty in the war, and then pressed Tibbets to acknowledge that the indiscriminate bombing of civilians was always wrong.

But the pilot (who had not met one of the Japanese survivors previously) was non-committal in his response, while volunteering that wars were a very bad idea in the nuclear age. Takahashi swore he saw a tear in the corner of one of Tibbets' eyes.

So, on May 6, 1985, I called Tibbets at his office at Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, and in surprisingly short order, he got on the horn. He confirmed the meeting with Takahashi (he agreed to do that only out of "courtesy") and most of the details, but scoffed at the notion of shedding any tears over the bombing. That was, in fact, "bullshit."

So, on May 6, 1985, I called Tibbets at his office at Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, and in surprisingly short order, he got on the horn. He confirmed the meeting with Takahashi (he agreed to do that only out of "courtesy") and most of the details, but scoffed at the notion of shedding any tears over the bombing. That was, in fact, "bullshit."

"I've got a standard answer on that," he informed me, referring to guilt. "I felt nothing about it. I'm sorry for Takahashi and the others who got burned up down there, but I felt sorry for those who died at Pearl Harbor, too....People get mad when I say this but -- it was as impersonal as could be. There wasn't anything personal as far as I?m concerned, so I had no personal part in it.

"It wasn't my decision to make morally, one way or another. I did what I was told -- I didn't invent the bomb, I just dropped the damn thing. It was a success, and that's where I've left it. I can assure you that I sleep just as peacefully as anybody can sleep." When August 6 rolled around each year "sometimes people have to tell me. To me it's just another day."

In fact, he wrote in his autobiography, The Tibbets Story, that President Truman at a meeting in the White House after the bombing had instructed him not to lose any sleep over it. "His advice was appreciated but unnecessary," Tibbets explained.

In any event, Tibbets (like Truman) had acted in a consistent manner for decades, while at times traveling under an assumed name to avoid scrutiny. After the war he called Hiroshima and Nagasaki "good virgin targets" -- they had been untouched by pre-atomic air raids -- and ideal for "bomb damage studies." In 1976, as a retired brigadier general, he re-enacted the Hiroshima mission at an air show in Texas, with a smoke bomb set off to simulate a mushroom cloud. He intended to do it again elsewhere, but international protests forced a cancellation.

He told a Washington Post reporter, for a favorable profile, in 1996, "For awhile in the 1950s, I got a lot of letters condemning me...but they faded out." On the other hand, "I got a lot of letters from women propositioning me."

In Atomic Cover-up, I recalled Tibbets' role as a paid consultant to the 1953 Hollywood movie, Above and Beyond, with Robert Taylor in the pilot role. In the key scene, after releasing the bomb and watching Hiroshima go up in flames below, Taylor radios in a strike report. "Results good," he says. Then he repeats it, bitterly and with grim irony.

But that was not in the Tibbets-approved original script for the film. It was added later, presumably to show that the men who dropped the bomb recognized the tragic nature of their mission.

Tibbets criticized the scene when the film came out.

I had a chance to interview Tibbets nearly 30 years ago, and wrote about it for several newspapers and magazines and in the book I wrote, Atomic Cover-up . Later I got to meet and sit next to the pilot who dropped the bomb over Nagasaki, Charles Sweeney, on Larry King's CNN show. I wonder how many other writers have met both of them (and also journeyed to the two atomic cities and met dozens of survivors).

The hook for the Tibbets interview was this: While spending a month in Japan on a grant in 1984, I met a man named Akihiro Takahashi. He was one of the many child victims of the atomic attack, but unlike most of them, he survived (though with horrific burns and other injuries), and grew up to become a director of the memorial museum in Hiroshima.

Takahashi showed me personal letters to and from Tibbets, which had led to a remarkable meeting between the two elderly men in Washington, D.C. At that recent meeting, Takahashi expressed forgiveness, admitted Japan's aggression and cruelty in the war, and then pressed Tibbets to acknowledge that the indiscriminate bombing of civilians was always wrong.

But the pilot (who had not met one of the Japanese survivors previously) was non-committal in his response, while volunteering that wars were a very bad idea in the nuclear age. Takahashi swore he saw a tear in the corner of one of Tibbets' eyes.

So, on May 6, 1985, I called Tibbets at his office at Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, and in surprisingly short order, he got on the horn. He confirmed the meeting with Takahashi (he agreed to do that only out of "courtesy") and most of the details, but scoffed at the notion of shedding any tears over the bombing. That was, in fact, "bullshit."

So, on May 6, 1985, I called Tibbets at his office at Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, and in surprisingly short order, he got on the horn. He confirmed the meeting with Takahashi (he agreed to do that only out of "courtesy") and most of the details, but scoffed at the notion of shedding any tears over the bombing. That was, in fact, "bullshit.""I've got a standard answer on that," he informed me, referring to guilt. "I felt nothing about it. I'm sorry for Takahashi and the others who got burned up down there, but I felt sorry for those who died at Pearl Harbor, too....People get mad when I say this but -- it was as impersonal as could be. There wasn't anything personal as far as I?m concerned, so I had no personal part in it.

"It wasn't my decision to make morally, one way or another. I did what I was told -- I didn't invent the bomb, I just dropped the damn thing. It was a success, and that's where I've left it. I can assure you that I sleep just as peacefully as anybody can sleep." When August 6 rolled around each year "sometimes people have to tell me. To me it's just another day."

In fact, he wrote in his autobiography, The Tibbets Story, that President Truman at a meeting in the White House after the bombing had instructed him not to lose any sleep over it. "His advice was appreciated but unnecessary," Tibbets explained.

In any event, Tibbets (like Truman) had acted in a consistent manner for decades, while at times traveling under an assumed name to avoid scrutiny. After the war he called Hiroshima and Nagasaki "good virgin targets" -- they had been untouched by pre-atomic air raids -- and ideal for "bomb damage studies." In 1976, as a retired brigadier general, he re-enacted the Hiroshima mission at an air show in Texas, with a smoke bomb set off to simulate a mushroom cloud. He intended to do it again elsewhere, but international protests forced a cancellation.

He told a Washington Post reporter, for a favorable profile, in 1996, "For awhile in the 1950s, I got a lot of letters condemning me...but they faded out." On the other hand, "I got a lot of letters from women propositioning me."

In Atomic Cover-up, I recalled Tibbets' role as a paid consultant to the 1953 Hollywood movie, Above and Beyond, with Robert Taylor in the pilot role. In the key scene, after releasing the bomb and watching Hiroshima go up in flames below, Taylor radios in a strike report. "Results good," he says. Then he repeats it, bitterly and with grim irony.

But that was not in the Tibbets-approved original script for the film. It was added later, presumably to show that the men who dropped the bomb recognized the tragic nature of their mission.

Tibbets criticized the scene when the film came out.

Published on August 11, 2013 20:03

Baseball at Ground Zero

After more than a week in Hiroshima, it was time for the ultimate evening escape for a baseball fan: a Hiroshima Toyo Carp game. At my request, the foundation sponsoring my month-long research trip to Hiroshima and Nagasaki had secured seats for the visiting journalists right behind home plate, about eight feet from the screen. Naturally a TV crew came along to catch our reaction, or perhaps the Japanese fans' reaction to us.

After more than a week in Hiroshima, it was time for the ultimate evening escape for a baseball fan: a Hiroshima Toyo Carp game. At my request, the foundation sponsoring my month-long research trip to Hiroshima and Nagasaki had secured seats for the visiting journalists right behind home plate, about eight feet from the screen. Naturally a TV crew came along to catch our reaction, or perhaps the Japanese fans' reaction to us.Thanks to my interviews with Sadaharu Oh and Roy White (the former Yankees star who then went to the Tokyo Giants) a few years back, I knew quite a bit about Japanese baseball. It had been around for at least half a century. One of the U.S. military team that I write about in my new book Atomic Cover-up told me he filmed boys playing ball in the atomic ruins (the footage was suppressed for decades). Hiroshima's stadium was a somewhat ramshackle, single-level shell, about the size of a Triple A park in my country. Its location: directly across from ground zero, no more than a couple of home runs away.

Taking a seat at the stadium proved unnerving. For one thing, the A-Bomb Dome loomed over the third base rim of the stadium, a reminder that this ball field was once a killing field. Then there were the fans, laughing and pointing at us: Look at the Americans watching the American pastime in Hiroshima (of all places). The irony was so thick you could cut it with a ... bat.

To welcome its first pro team, Hiroshima erected the stadium in the early 1950s. The mayor hoped baseball would "revitalize the spirit of Hiroshima," and make the citizens forget what had happened on August 6, 1945, four decades before my visit. Yet he built the stadium 300 yards from the epicenter of the atomic explosion.

There was no evidence that the fans felt particularly uncomfortable in this setting. A majority of adults in this city were survivors of the bomb, or lost parents that day, or were related to hibakusha, yet thousands come to this spot where so many perished to drink beer and cheer. Among the players they applauded were hired mercenaries from the country that dropped the bomb on their relatives (or themselves).

Out of guilt or uneasiness, I found myself cheering loudly for the Carp, as if this could somehow compensate for the decision to drop the bomb. Still, this was once a killing field, and any fan raising his or her eyes could see that spot in the sky where the bomb went off.

For a baseball fan from New York, it was hard to enjoy the game. At Yankee Stadium you get a screeching subway; at the Mets' home field, jumbo jets from LaGuardia. At Hiroshima Stadium, for decades, you got the A-bomb Dome over your shoulder. It is often said that the ghosts of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig haunt Yankee Stadium. One did not want to think too deeply, especially at a baseball game, about the apparition potential at Hiroshima Stadium.

There is this postscript: A new baseball stadium for the Carp, located closer to Hiroshima Station than the A-Bomb Dome, opened in 2009. Naming rights were purchased by Mazda, whose main auto plant for Japan is located on the outskirts of the city. (It was only partly destroyed in 1945, as I learned in a visit there.) The formal name for the new structure is the Mazda Zoom-Zoom Stadium.

Published on August 11, 2013 15:47

August 10, 2013

Ohio Sunset Over Wrecked Barn

Published on August 10, 2013 21:00

When First U.S. Reporter Reached Nagasaki--and His Reports Suppressed

Nagasaki, which lost over 70,000 civilians (and a few military personnel) to a new weapon 68 years ago yestered, has always been The Forgotten A-Bomb City. No one ever wrote a bestselling book called Nagasaki, or made a film titled Nagasaki, Mon Amour. Yet in some ways, Nagasaki is the modern A-bomb city. For one thing, when the plutonium bomb exploded above Nagasaki it made the uranium-type bomb dropped on Hiroshima obsolete. In fact, if it had not exploded off-target, the death toll in the city would have easily topped the Hiroshima total.

But Nagasaki was "forgotten" from the very start, thanks to a blatant act of press censorship.

One of the great mysteries of the Nuclear Age was solved just eight years ago: What was in the censored, and then lost to the ages, newspaper articles filed by the first reporter to reach Nagasaki following the atomic attack on that city on Aug. 9, 1945.

The reporter was George Weller, the distinguished correspondent for the now-defunct Chicago Daily News. His startling dispatches from Nagasaki, which could have affected public opinion on the future of the bomb, never emerged from General Douglas MacArthur's censorship office in Tokyo. I wrote about this cover-up in the book Atomic Cover-up, along the suppression for decades of film footage shot in the two atomic cities by the U.S. military.

Carbon copies of the stories were found in 2003 when his son discovered them after the reporter's death. Four of them were published in 2005 for the first time by the Tokyo daily Mainichi Shimbun, which purchased them from the son, Anthony Weller. I was first to report on this in the United States.

Carbon copies of the stories were found in 2003 when his son discovered them after the reporter's death. Four of them were published in 2005 for the first time by the Tokyo daily Mainichi Shimbun, which purchased them from the son, Anthony Weller. I was first to report on this in the United States.

The articles published in Japan (and later included in a book assembled by Anthony Weller, First Into Nagasaki) revealed a remarkable and wrenching turn in Weller's view of the aftermath of the bombing, which anticipates the profound unease in our nuclear experience ever since. "It was remarkable to see that shifting perspective," Anthony Weller told me.

An early article that George Weller filed, on Sept. 8, 1945 -- two days after he reached the city, before any other journalist -- hailed the "effectiveness of the bomb as a military device," as his son describes it, and made no mention of the bomb's special, radiation-producing properties.

But later that day, after visiting two hospitals and shaken by what he saw, he described a mysterious "Disease X" that was killing people who had seemed to survive the bombing in relatively good shape. A month after the atomic inferno, they were passing away pitifully, some with legs and arms "speckled with tiny red spots in patches."

The following day he again described the atomic bomb's "peculiar disease" and reported that the leading local X-ray specialist was convinced that "these people are simply suffering" from the bomb's unknown radiation effects.

Anthony Weller, a novelist, told me that it was one of great disappointments of his father's life that these stories, "a real coup," were killed by MacArthur who, George Weller felt, "wanted all the credit for winning the war, not some scientists back in New Mexico."

Others have suggested that the real reason for the censorship was the United States did not want the world to learn about the morally troubling radiation effects for two reasons: It aimed to avoid questions raised about the use of the weapon in 1945, or its wide scale development in the coming years. In fact, an official "coverup" of much of this information--involving print accounts, photographs and film footage--continued for years, even, in some cases, decades.

"Clearly," Anthony Weller told me of his father's reports, "they would have supplied an eyewitness account at a moment when the American people badly needed one."

The Scoop That Wasn't

How did George Weller get the scoop-that-wasn't?

After years of covering the Pacific war, Weller (left) arrived in Japan with the first wave of reporters and military in early September. He had already won a Pulitzer for his reporting in 1943. Appalled by MacArthur's censors, and "the conformists" in his profession who went along with strict press restrictions, he made his way, with permission, to the distant island of Kyushu to visit a former kamikaze base. But he noted that it was connected by railroad to Nagasaki. Pretending he was "a major or colonel," as his son put it, he slipped into the city (perhaps by boat) about three days before any of his colleagues, and just after Wilfred Burchett had filed his first report from Hiroshima.

Once arrived, Weller toured the city, the aid stations, the former POW camps (by some counts, more American POWs died from the A-bomb in Nagasaki than Japanese military personnel) and wrote numerous stories within days. According to his son, he managed to send the articles to Tokyo, not by wire, but by hand, and felt "that the sheer volume and importance of the stories would mean they would be respected" by MacArthur and his censors.

Although Weller did not express any outward disapproval of the use of the bomb, these stories -- and others he filed in the following two weeks from the vicinity -- would never see the light of the day, and the reporter lost track of his carbons. He would later summarize the experience with the censorship office in two words: "They won."

In the years that followed, Weller continued his journalism career, winning a George Polk award and other honors and covering many other conflicts. Neither the carbons nor the originals ever surfaced, before he passed away in 2002 at the age of 95. It was then that his son made a full search of the wildly disorganized "archives" at his father's home in Italy, and in 2003 found the carbons just 30 feet from his dad's desk.

And what a find: roughly 75 pages of stories, on fading brownish paper, that covered not only his first atomic dispatches but gripping accounts by prisoners of war, some of whom described watching the bomb go off on that fateful morning.

A 'Peculiar Weapon'

In the first article published by the Japanese paper, the first words from Weller were: "The atomic bomb may be classified as a weapon capable of being used indiscriminately, but its use in Nagasaki was selective and proper and as merciful as such a gigantic force could be expected to be." Weller described himself as "the first visitor to inspect the ruins."

He suggested about 24,000 may have died but he attributed the high numbers to "inadequate" air raid shelters and the "total failure" of the air warning system. He declared that the bomb was "a tremendous, but not a peculiar weapon," and said he spent hours in the ruins without apparent ill effects. He did note, with some regret, that a hospital and an American mission college were destroyed, but pointed out that to spare them would have also meant sparing munitions plants.

In his second story that day, however, following his hospital visits, he would describe "Disease X," and victims, who have "neither a burn or a broken limb," wasting away with "blackish" mouths and red spots, and small children who "have lost some hair."

A third piece, sent to MacArthur the following day, reported the disease "still snatching away lives here. Men, women and children with no outward marks of injury are dying daily in hospitals, some after having walked around three or four weeks thinking they have escaped.

"The doctors ... candidly confessed ... that the answer to the malady is beyond them." At one hospital, 200 of 343 admitted had died: "They are dead -- dead of atomic bomb -- and nobody knows why."

He closed this account with: "Twenty-five Americans are due to arrive Sept. 11 to study the Nagasaki bomb site. Japanese hope they will bring a solution for Disease X." To this day, that solution for the disease--and the threat of nuclear weapons--has still not arrived.

More on suppression of evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Atomic Cover-up .

But Nagasaki was "forgotten" from the very start, thanks to a blatant act of press censorship.

One of the great mysteries of the Nuclear Age was solved just eight years ago: What was in the censored, and then lost to the ages, newspaper articles filed by the first reporter to reach Nagasaki following the atomic attack on that city on Aug. 9, 1945.

The reporter was George Weller, the distinguished correspondent for the now-defunct Chicago Daily News. His startling dispatches from Nagasaki, which could have affected public opinion on the future of the bomb, never emerged from General Douglas MacArthur's censorship office in Tokyo. I wrote about this cover-up in the book Atomic Cover-up, along the suppression for decades of film footage shot in the two atomic cities by the U.S. military.

Carbon copies of the stories were found in 2003 when his son discovered them after the reporter's death. Four of them were published in 2005 for the first time by the Tokyo daily Mainichi Shimbun, which purchased them from the son, Anthony Weller. I was first to report on this in the United States.

Carbon copies of the stories were found in 2003 when his son discovered them after the reporter's death. Four of them were published in 2005 for the first time by the Tokyo daily Mainichi Shimbun, which purchased them from the son, Anthony Weller. I was first to report on this in the United States.The articles published in Japan (and later included in a book assembled by Anthony Weller, First Into Nagasaki) revealed a remarkable and wrenching turn in Weller's view of the aftermath of the bombing, which anticipates the profound unease in our nuclear experience ever since. "It was remarkable to see that shifting perspective," Anthony Weller told me.

An early article that George Weller filed, on Sept. 8, 1945 -- two days after he reached the city, before any other journalist -- hailed the "effectiveness of the bomb as a military device," as his son describes it, and made no mention of the bomb's special, radiation-producing properties.

But later that day, after visiting two hospitals and shaken by what he saw, he described a mysterious "Disease X" that was killing people who had seemed to survive the bombing in relatively good shape. A month after the atomic inferno, they were passing away pitifully, some with legs and arms "speckled with tiny red spots in patches."

The following day he again described the atomic bomb's "peculiar disease" and reported that the leading local X-ray specialist was convinced that "these people are simply suffering" from the bomb's unknown radiation effects.

Anthony Weller, a novelist, told me that it was one of great disappointments of his father's life that these stories, "a real coup," were killed by MacArthur who, George Weller felt, "wanted all the credit for winning the war, not some scientists back in New Mexico."

Others have suggested that the real reason for the censorship was the United States did not want the world to learn about the morally troubling radiation effects for two reasons: It aimed to avoid questions raised about the use of the weapon in 1945, or its wide scale development in the coming years. In fact, an official "coverup" of much of this information--involving print accounts, photographs and film footage--continued for years, even, in some cases, decades.

"Clearly," Anthony Weller told me of his father's reports, "they would have supplied an eyewitness account at a moment when the American people badly needed one."

The Scoop That Wasn't

How did George Weller get the scoop-that-wasn't?

After years of covering the Pacific war, Weller (left) arrived in Japan with the first wave of reporters and military in early September. He had already won a Pulitzer for his reporting in 1943. Appalled by MacArthur's censors, and "the conformists" in his profession who went along with strict press restrictions, he made his way, with permission, to the distant island of Kyushu to visit a former kamikaze base. But he noted that it was connected by railroad to Nagasaki. Pretending he was "a major or colonel," as his son put it, he slipped into the city (perhaps by boat) about three days before any of his colleagues, and just after Wilfred Burchett had filed his first report from Hiroshima.

Once arrived, Weller toured the city, the aid stations, the former POW camps (by some counts, more American POWs died from the A-bomb in Nagasaki than Japanese military personnel) and wrote numerous stories within days. According to his son, he managed to send the articles to Tokyo, not by wire, but by hand, and felt "that the sheer volume and importance of the stories would mean they would be respected" by MacArthur and his censors.

Although Weller did not express any outward disapproval of the use of the bomb, these stories -- and others he filed in the following two weeks from the vicinity -- would never see the light of the day, and the reporter lost track of his carbons. He would later summarize the experience with the censorship office in two words: "They won."

In the years that followed, Weller continued his journalism career, winning a George Polk award and other honors and covering many other conflicts. Neither the carbons nor the originals ever surfaced, before he passed away in 2002 at the age of 95. It was then that his son made a full search of the wildly disorganized "archives" at his father's home in Italy, and in 2003 found the carbons just 30 feet from his dad's desk.

And what a find: roughly 75 pages of stories, on fading brownish paper, that covered not only his first atomic dispatches but gripping accounts by prisoners of war, some of whom described watching the bomb go off on that fateful morning.

A 'Peculiar Weapon'

In the first article published by the Japanese paper, the first words from Weller were: "The atomic bomb may be classified as a weapon capable of being used indiscriminately, but its use in Nagasaki was selective and proper and as merciful as such a gigantic force could be expected to be." Weller described himself as "the first visitor to inspect the ruins."

He suggested about 24,000 may have died but he attributed the high numbers to "inadequate" air raid shelters and the "total failure" of the air warning system. He declared that the bomb was "a tremendous, but not a peculiar weapon," and said he spent hours in the ruins without apparent ill effects. He did note, with some regret, that a hospital and an American mission college were destroyed, but pointed out that to spare them would have also meant sparing munitions plants.

In his second story that day, however, following his hospital visits, he would describe "Disease X," and victims, who have "neither a burn or a broken limb," wasting away with "blackish" mouths and red spots, and small children who "have lost some hair."

A third piece, sent to MacArthur the following day, reported the disease "still snatching away lives here. Men, women and children with no outward marks of injury are dying daily in hospitals, some after having walked around three or four weeks thinking they have escaped.

"The doctors ... candidly confessed ... that the answer to the malady is beyond them." At one hospital, 200 of 343 admitted had died: "They are dead -- dead of atomic bomb -- and nobody knows why."

He closed this account with: "Twenty-five Americans are due to arrive Sept. 11 to study the Nagasaki bomb site. Japanese hope they will bring a solution for Disease X." To this day, that solution for the disease--and the threat of nuclear weapons--has still not arrived.

More on suppression of evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Atomic Cover-up .

Published on August 10, 2013 19:14

A New John Grisham Chiller--Gitmo

The famed author pens a piece for NYT Sunday opinion section re: Gitmo prisoners and hunger strike. Don't miss. Opens: "About two months ago I learned that some of my books had been banned at Guantánamo Bay. Apparently detainees were requesting them, and their lawyers were delivering them to the prison, but they were not being allowed in because of 'impermissible content.'” Then follow what happens next.

Published on August 10, 2013 18:22

August 9, 2013

Man in the Middle

The Wash Post charts all of new boss's political donations and declares that he is right in the middle of the spectrum, or as you may have heard, a "liberal-libertarian." As such, does that mean hawkish editorial page is on the way out? Probably not.

Published on August 09, 2013 06:10

August 8, 2013

Cowboy Jack Dies at 82

A true country legend, Jack Clement has passed away. His credits too long to mention, alhough I'll highlight discovering Jerry Lee Lewis, and writing for and producing Johnny Cash and, less famously, producing Townes Van Zandt. Even produced "Angel of Harlem" and "When Loves Comes to Town" for U2. "Cowboy" didn't like horses and favored Hawaiian shirts. Go figure. Plus he was famous for his home movies, here Johnny Cash:

Published on August 08, 2013 19:14

When Jon Stewart Apologized for Hitting Truman

In a piece here yesterday, I accused Harry Truman of perpetrating a "war crime" with his failure to pause after the Hiroshima bombing (itself a highly questionable act) to see if it, along with the Soviet declaration of war, would produce a swift Japanese surrender. He didn't, and on August 9, the second atomic bomb was dropped over Nagasaki, killing another 90,000, the vast majority women and children.

This remind me of an episode in the spring of 2009 featuring, of all people, Jon Stewart. One night he bravely (if off-handedly) suggested that President Harry Truman was a "war criminal" for using the atomic bomb against Japan without any prior warning. He explained: "I think if you dropped an atomic bomb fifteen miles off shore and you said, 'The next one's coming and hitting you,' then I would think it's okay. To drop it on a city, and kill a hundred thousand people. Yeah, I think that's criminal." (Actually, the United States used the bomb on two cities, killing 250,000.)

After he got a good deal of flack overnight, he offered a rare on-air, and abject, apology. (He could have at least said, Yeah, war criminal for Nagasaki, not so much for Hiroshima.) As I've documented in three books, this shows how the use of the bomb against Japan remains a "raw nerve" or "third rail" in America's psyche, and media. Here's the transcript, with the video below:

"The other night we had on Cliff May. He was on, we were discussing torture, back and forth, very spirited discussion, very enjoyable. And I may have mentioned during the discussion we were having that Harry Truman was a war criminal. And right after saying it, I thought to myself, that was dumb. And it was dumb. Stupid in fact.

"So I shouldn't have said that, and I did. So I say right now, no, I don't believe that to be the case. The atomic bomb, a very complicated decision in the context of a horrific war, and I walk that back because it was in my estimation a stupid thing to say. Which, by the way, as it was coming out of your mouth, you ever do that, where you're saying something, and as it's coming out you're like, 'What the f**k, nyah?'

"And it just sat in there for a couple of days, just sitting going, 'No, no, he wasn't, and you should really say that out loud on the show.' So I am, right now, and, man, ew. Sorry."

The Daily Show

Get More: Daily Show Full Episodes,The Daily Show on Facebook

This remind me of an episode in the spring of 2009 featuring, of all people, Jon Stewart. One night he bravely (if off-handedly) suggested that President Harry Truman was a "war criminal" for using the atomic bomb against Japan without any prior warning. He explained: "I think if you dropped an atomic bomb fifteen miles off shore and you said, 'The next one's coming and hitting you,' then I would think it's okay. To drop it on a city, and kill a hundred thousand people. Yeah, I think that's criminal." (Actually, the United States used the bomb on two cities, killing 250,000.)

After he got a good deal of flack overnight, he offered a rare on-air, and abject, apology. (He could have at least said, Yeah, war criminal for Nagasaki, not so much for Hiroshima.) As I've documented in three books, this shows how the use of the bomb against Japan remains a "raw nerve" or "third rail" in America's psyche, and media. Here's the transcript, with the video below:

"The other night we had on Cliff May. He was on, we were discussing torture, back and forth, very spirited discussion, very enjoyable. And I may have mentioned during the discussion we were having that Harry Truman was a war criminal. And right after saying it, I thought to myself, that was dumb. And it was dumb. Stupid in fact.

"So I shouldn't have said that, and I did. So I say right now, no, I don't believe that to be the case. The atomic bomb, a very complicated decision in the context of a horrific war, and I walk that back because it was in my estimation a stupid thing to say. Which, by the way, as it was coming out of your mouth, you ever do that, where you're saying something, and as it's coming out you're like, 'What the f**k, nyah?'

"And it just sat in there for a couple of days, just sitting going, 'No, no, he wasn't, and you should really say that out loud on the show.' So I am, right now, and, man, ew. Sorry."

The Daily Show

Get More: Daily Show Full Episodes,The Daily Show on Facebook

Published on August 08, 2013 10:30