Chris Baty's Blog, page 217

March 29, 2013

Why I'm Writing Memoir: Memoir is French for Awesome

This year during Camp NaNoWriMo, we want you to write whatever it is that you love. This week, writers of all sorts are sharing what they love to pen, and why you should join them. Today, Jen Larsen, author of Stranger Here , tells us why memoir begins with Truth with a capital T:

So when I was in grad school getting my MFA, the first class we took—mandatory for everyone in the program no matter what genre they were interested in—was a creative autobiography class.

The poets, the novelists, the non-fiction writers: we all had to sit in a room awkwardly together and figure out how to talk about ourselves. To turn our lives into a story. To find narrative where there isn’t any—because life isn’t a movie: it doesn’t open with a snappy sequence, lead into a climax with car crashes, then end with a happily ever after. The challenge of that class was to take all the messiness of life and the uncoordinated jumble inside of your head and turn it into something real, and readable.

To narrow it down to its finest point: the challenge was to take all the awfulness and sadness and absurdity of life, and tell the truth about it. To be completely, thoroughly, painfully honest. To viscerally understand that storytelling, even when it’s stories about zombies and death squads and fairy princesses (especially when it’s stories about fairy-zombie-princess death squads) is about capital-T truth at the end, and nothing else. And when you know how to tell the truth about Truth, everything else is gravy, right?

Story is the way we process our lives. The only way we have to really understand how people and events connect and change each other in millions of ways we’d never thought about until we saw them together on the page.

And memoir, memoir is absolutely transformative. It’s a way to take an experience—your most sublime, your most awful, your most embarrassing moments, your darkest and most hideous thoughts—and turn them into something beautiful, powerful, important. It’s a way to connect over the most real things you think and feel.

And sure, it’s self-indulgent to sit down and write your own story, to take a deep breath and dive in with the idea that someone is actually going to care about anything you’ve ever done or cared about. But any art is self-indulgence.

Every piece of art and writing (fiction, epic poetry, knock-knock jokes and zen koans) begins with its creator taking the risk that it is worth doing. That someone will actually care. Every single time we open up our laptops we’re taking the risk that what we’re doing won’t matter to anyone.

Except every single time we open up our laptops, we’re doing something that matters. Even when it’s not good. Even when it’s messy and sad and strange and not exactly what we meant to say or ever expected to say. Especially then. It matters because the story you’ve got to tell about yourself is the story that’s the basis of every other thing you will ever write. It’s the essential essence of who you are and how you look at the world.

To write that down and understand it and see it and think about it—that transforms you as a writer. It transforms how you think not just about storytelling, but about yourself as a storyteller. It’s where you find the truth you want to tell, and how you start figuring out exactly how to tell it.

Jen Larsen is the author of Stranger Here: How Weight Loss Surgery Transformed My Body and Messed With My Head . She has an MFA in creative writing from the University of San Francisco and currently lives in Ogden, UT.

Photo by Flickr user Cali4beach.

March 28, 2013

Why I'm Writing Poetry: The Diversity of NaPoWriMo

This year during Camp NaNoWriMo, we want you to write what you love, whether that’s a novel or not. This week, writers of all kinds will share what they’ll be penning this April, and why you should join them. Ready for our second Camp Elective? Maureen Thorson, founder of National Poetry Writing Month (which we don’t run but do appreciate!), tells us why you should flock to poetry:

Identifying as a poet is a strange business. After all, how do you know you’re a poet? There’s nowhere to apply for a license. Do you need to clock a certain number of hours at open mike readings in coffee shops? Get an MFA? What if you just stand out on the sidewalk and announce, “I’m a poet”? Will all of the “real” poets come out of the woodwork to shame you?

Happily, no. (Although passersby might give you a wide berth until you stop making odd public announcements). As it turns out, there’s not much to being a poet, except writing poems.

So there’s the rub! How do you get started with writing poems? Well, like anything, one gets better and more comfortable with practice, and that’s where National Poetry Writing Month comes in.

In similar spirit to Camp NaNoWriMo, NaPoWriMo invites you (and you! and you, too?!) to write a poem every day for April. Back in 2003, I loved poetry, but I didn’t know any poets. Still, I decided to give myself the challenge to write 30 poems in 30 days—and I made it! Starting NaPoWriMo kickstarted my work when I was feeling lonely and low.

The next year, I moved to New York, and actually met some poets. And like me, they sometimes had trouble writing: with no ideas, and no formal writing deadlines, their writing would slow way down. It turns out that writer’s block is universal. So when April came around, I decided to repeat the challenge, and this time, some of my poet friends joined me.

Since then, published poets and unpublished poets have tackled poetry with us in April. People who’ve been writing poems their whole lives, and people who’ve just decided to start now. Kids and grandparents. Book clubs and elementary school classes. And there are books that exist today because poets decided to shake up their writing routine and write those thirty poems under deadline.

So how do you participate in NaPoWriMo? At its most basic, just write a poem every day for April! If you’re so inclined, you can start a blog where you’ll post your work, and submit it to us on our site. You can also get a peek at other people’s efforts, access a poetry prompt each day, and check out daily poetry-related links. And sure enough, you can also use Camp NaNoWriMo to organize your poems, reach out to other writers and keep track of your poetry-writing goals!

For me, one of the most gratifying things about NaPoWriMo is how many poets come back each year, like the swallows to Capistrano. Not everyone makes it the full thirty days, but they come back and try again. And the poems that result are wonderfully diverse, just as the participants are; all forms, styles and subject matter are represented. Heck, for the past two years we’ve even had one guy who writes poems entirely about masonry!

Writing poems doesn’t have to be scary. There is no application process. All it takes is a little gumption, and a willingness to open your mind to the possibility that you, too, can write poems.

Maureen Thorson’s first book of poetry, Applies to Oranges, was published in 2011 by Ugly Duckling Presse. She began NaPoWriMo in 2003, and currently hosts its site, where poets can share their writing efforts. She lives in Washington, DC, where she co-curates the In Your Ear reading series at the DC Arts Center, and is the poetry editor of Open Letters Monthly, an online arts and literature review.

Photo by Flickr user meilev.

March 27, 2013

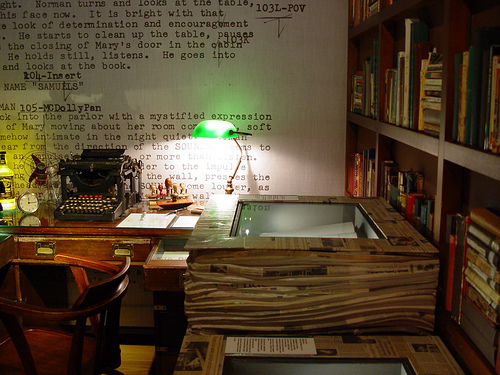

The Script Cabins: Writing for TV 101

We’re rolling out the red carpet to the Script Cabins at Camp NaNoWriMo. This is the fourth and final guide for all you future screenwriters, playwrights, and graphic novelists, and we’re tackling that most familiar of mediums: television!

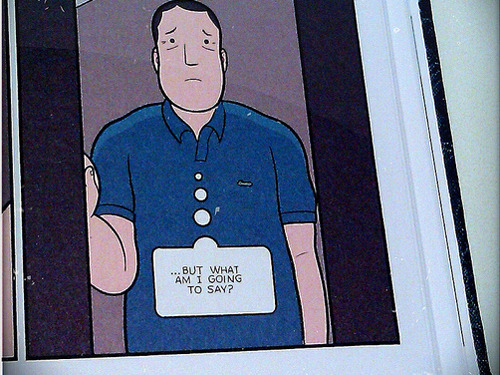

There’s not a person writing television today who didn’t start off sitting alone at their desk, wondering who the heck they were trying to fool. What made them special is that they didn’t give it up.

If you’ve never written a TV script before, fear not. As you move through the pointers below, you’ll probably realize that most of them are already second nature:

To Spec or Not To Spec

Ten years ago, if you wanted to be a TV scribe, you had to start by writing fake episodes for existing shows on “speculation” of purchase, or “on spec”. Today, executives are just as likely to ask for a pilot script as they are for a spec. Some even prefer pilots to spec scripts, as pilot scripts tend to show off the unique voice of a new writer.

Still, each is a useful tool in marketing yourself as a writer, so the question comes down to what you want to write.

Know Your Show

If you’re thinking about writing a spec, start by focusing on a fresh, highly-rated show currently airing within a genre that you love. Once you’ve targeted a show, get your hands on a written episode using websites like Daily Script, and format yours as similarly as possible.

If you plan to write your own pilot, start by watching shows you think might be similar. Make note of how they’re structured and what types of situations comprise the main storylines.

What A Character!

Television writers keep their audience hooked with strong characters. Knowing your characters inside and out is fundamental to good story structure and dialogue.

Try writing who you know, but without the boring stuff. Drop your dad, or your girlfriend, or your sixth-grade math teach into the mix, and see how they fare next to your shape-shifting alien or talking dog

TV characters should be crystal clear and set up in obvious conflict with others in the very first episode. Your job is to keep this initial dynamic familiar. If you’re writing a spec, do not try to take the show in a bold new direction—stick to the characters the way they are.

Talk the Talk

Before worrying about how to make your characters talk like they’re in a TV show, you’ll need to give them something to talk about. If you know your characters and their goals, your dialogue will begin to write itself.

Remember: there is a real difference between “dialogue” and “conversation”. Your characters should be sharper and quicker than most of us are in real life. Always be sure to read your lines out loud. You’re not writing a novel—these words are meant to be spoken, and you may be surprised by how differently dialogue can play outside of your head.

House of Cards

Whatever type of script you’re writing, it’s helpful to think about your story in terms of several acts broken up by commercial breaks.

Half-hour sitcoms tend to unfold in the following manner:

Teaser

Act 1

Act 2

Tag

Whereas hour-long shows usually unfold like so:

Teaser

Act 1

Act 2

Act 3

Act 4

The rule of thumb is that one page of writing generally equals just under one minute of air time, so hour-long dramas tend to be about sixty pages long, and half-hour network shows tend to be about twenty to thirty pages.

Learn Your ABC’s

Think about your script as traveling down two or three separate roads at the same time. Your A-plot fuels the actions of the main characters and pushes the story along. Your B-plot expresses the emotional entanglements and problems of your main characters. Hour-long shows have a C-plot, focusing on the parallel lives of supporting characters.

Each of your acts should contain a 60/30/10 breakdown of your A, B and C-plots, respectively. In a half hour show with no C-plot, the ratio should be closer to 60/40.

The A, B, Cs are negotiable, but this next rule is not: Each act must end in a genuine ‘cliffhanger.’ Always arrange your scenes so that your big, juicy moments fall just before your breaks.

The Fun Is In The…

Writing should be fun! Whatever your reasons for starting down this path, they probably haven’t changed. Writing is awesome. And you’re awesome for wanting to be a writer. So no more procrastination! Back at it, my friend: we’re almost ready to start!

Adapted from Script Frenzy’s “Intro to TV Scripts” guide.

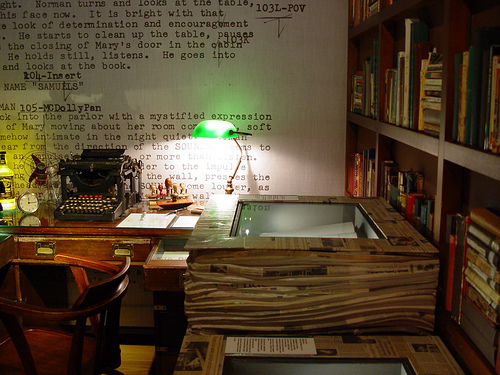

Photo by Flickr user Rantes.

March 26, 2013

Why I'm Writing Flash Fiction: The Benefits of Brevity

Camp NaNoWriMo began because we knew your writing couldn’t be contained, especially not by November. And this April and July, we’re pulling all the stops, and challenging you to write whatever it is that you love. This week, we’ll host writers of all stripes to tell us what style they’re tackling, and why. Grant Faulkner, Camp’s Head Counselor, starts us off by telling you why he’s going bite-size:

The biggest conundrum for most parent-writers is finding the time to write. I used to love waking up to a quiet house and the inspiring scents of a pot of coffee and dawdling through hours of uninterrupted writing time. Now I’m greeted by small creatures who ask me to feed them, entertain them, resolve their conflicts, schedule their social affairs, and chauffeur them about town.

One way I’ve learned to co-exist with this new life of harried time constraints is to write flash fiction—also known as short shorts, microfiction, postcard fiction, smokelongs, quick fiction, dribbles, drabbles, and seemingly a hundred other names (even nanofiction!).

Writing flash is a good break from noveling for me simply because it provides such a quick sense of accomplishment. I can write a flash story in the 15 minutes I have after dropping off the kids at school before work, and then edit it after dinner.

Writing flash also helps my noveling. It’s paradoxical, I know. A novel is all about bigness. Stories that are 100, or 500, or even 1,000 words max are all about smallness. But I always struggle to balance how much readers need to know in a novel with how much to leave out to create suspense. Writing flash is all about creating a story through its gaps and disconnections, though. The spectral quality of what’s left out matters as much as what’s left in, perhaps even more so.

Writing flash fiction also helps me with my current novel revision since it’s as much about pruning as it is about writing (although, trust me, “writing with abandon” can apply to a first draft of even the shortest story). I might write a 750-word story, and then cut it down to 500. With such a mindset, I find I revise my big tangled skein of a novel with a keener sense of the benefits of brevity.

That’s why I’m excited to write 30 Short Shorts in 30 Days during Camp NaNoWriMo. One of my New Year’s Resolutions this year is to put together a collection of one hundred 100-word stories by the end of the year.

Although I’m not going to write 50,000 words, writing a new story each day is its own challenge because I’ll need to come up with a new story idea each day. The planner in me is putting together 30 prompts beforehand to ward off any blocks.

So I’d love to hear your prompts. One of my favorite things about NaNo is the “writing together” that is at the core of the experience. Post a prompt in the comments below, and I’ll write a piece of nanofiction to it.

Photo by Flickr user wmshc_kiwi.

March 25, 2013

Designer Q&A: Brad Woodard on Creating With Purpose

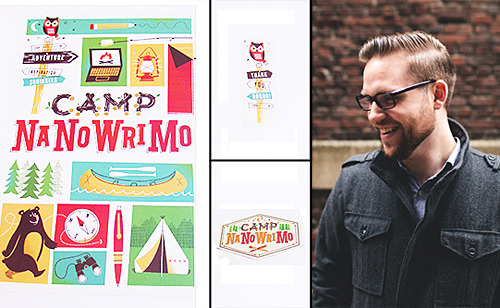

This year’s beautiful Camp design (including the 2013 shirt, and web badges!) was done by the incredibly talented Brad Woodard. We were lucky enough to get the chance to pick his brain about inspiration, the perfect book cover, and one particularly close encounter with a moose:

What can you tell us about the inspiration behind the design? Can you talk us through the process of putting the poster together?

The inspiration for this poster came from a lot of the memories I had of going to scout camps growing up. I had so many ideas for things to incorporate that it was really hard to decide what made it in. Having so many elements to choose from made it kind of like a puzzle, trying to fill spaces around the Camp NaNoWriMo text.

Once I finally managed to fit it all in, I had to do a lot with textures and colors to make sure it all balanced out at the end. I heard you all like the bear, and that was in there because of the number of bears I’ve run into in my years of camping in the mountains. Just felt right.

How would you describe your artistic style?

My artist style is playful, but very much influenced by my design background. I love to experiment with all of the design elements in my work: lines, textures, patterns, colors; they’re Legos to me. I can sit down with the same box of Legos every day and come up with something new to build each time.

I notice certain geometrical figures feature prominently in your work. Is that a deliberate choice on your part?

I struggled with every math course I ever took, except for geometry. As abstract as we think nature is, at it its core, it is all geometry. I love searching for those relationships in everything I illustrate. It is challenging, but super rewarding.

And what’s your dream project?

My dream project would be to illustrate the side of a U-Haul truck, or to illustrate a children’s book.

So let’s get serious. Are you an avid camper?

Actually yes, I’ve been camping since before I could walk. Then when I turned six, my dad started me backpacking, and I haven’t stopped.

One time, my buddies and I left for a backpacking trip in the Teton Mountains completely unprepared. Thinking we were in better shape than we were, we chose a climb without really looking at just how steep the elevation gain would be. We didn’t even bring enough food. After a brutal climb to the top, we were sunburned, exhausted and noticed that it was starting to snow. In our hurry to find a spot to ditch our backpacks, eat, then hide in our tents to sleep and get warm, we made a big mistake. We parked our tents right next to a stream.

Now if you are a hiker, you know full well that camping that close to water is a bad idea because animals come to the water to drink. And after about an hour of sleep, I was woken up by heaving panting and snorting. I opened my eyes only to see the silhouette of a massive moose head chewing on the tent poles. Not knowing how I should react, I remained as quiet and still as I could.

Unfortunately my buddy sleeping in the tent with me was wrapped up in a space blanket. So when I attempted to wake him up, he startled and sprang up to a sitting position, all the while making a ton of noise. The moose started stomping at the sides of the tent, and we had to back and forth between either end of the tent to avoid getting crushed by his massive hoof. For something that eventually ended after maybe three minutes, it felt like an eternity. Luckily for us, our fellow campers heard the commotion and scared off the moose.

So I don’t know if that was my best camping experience, but it was certainly the best story.

You have included a picture of a wild bear. Most people agree that wild bears are an awesome combination of power and cuddliness. If you were suddenly imbued with the power to speak “bear”, what would your first question be for these forest creatures and why?

If I could speak “bear” I would ask them what expression they use for when they are super hungry. As humans, we often say we are “as hungry as a bear”. What are they as hungry as?

It’s been said to never judge a book by its cover. However, as a graphic designer, what are the elements of your perfect book cover?

I think perfect book covers leave you with a feeling of wanting. They tease you with a glimpse of what might be contained inside, or with a cover so well-executed that you can’t help but think the content inside was created with the same level of quality.

If you decided to take on Camp NaNoWriMo, what would you write?

It would definitely be an adventure novel.

The NaNoWriMo community consists of many aspiring artists. What’s the best piece of advice you received as a budding creative?

Don’t be afraid to experiment. Get out of your comfort zone and play. And always remember to create with a purpose.

Brad Woodard is a graphic designer and illustrator raised in the Great Northwest, now living in Boston with his wife and little boy. Currently, he works as a designer during the day at Arnold Worldwide, and by night he runs Brave the Woods.

March 22, 2013

The Script Cabins: Writing a Play 101

We’re rolling out the red carpet to the Script Cabins at Camp NaNoWriMo. This is the third of our guides for all you future screenwriters, playwrights, and graphic novelists. Remember us at the Tonys!:

All great stage productions start with a script: it’s the cornerstone from which the actors, designers, and directors take their cues.

When writing a first draft of a play, it’s best not to concern yourself too much about how it will be performed. It’s more important to get your idea onto the page.

STARTING YOUR PLAY

Start with character basics: their ages and relationships to each other. Keep a list of these, known as the “Dramatis Personae”, or Cast of Characters. For yourself, you’ll want to know what drives each of the characters: their ambitions, their fears, their secrets.

Focus on the setting, determining time period, items needed on stage, and location in the world. Place clues here to the style of your play. A children’s play may be stylized in a cartoonish manner, while your melodrama may want a Gothic touch.

Remember, stage directions are not narration. They exist to give the actors, designers, and director a sense of what transpires on stage; not every outfit, attitude, or set detail needs to be included.

You should include:

Basic setting description

Entrances and exits

Physical action necessary for the dialogue to make sense

Pertinent pauses in the dialogue, if not filled by action that is previously mentionedAvoid including:

Tone of voice or delivery hints for every line

Full descriptions of each costume

Background on the sets or characters other than basic relationships

Characters’ thoughts or intention

STRUCTURING YOUR PLOT

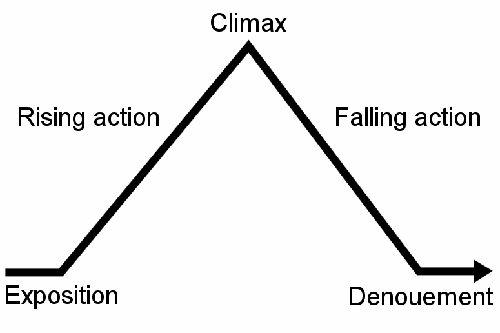

Freytag’s Pyramid (above) shows a very basic structure of modern drama. It’s more of an observation about plays throughout the years and is only a guide. There are lots of great works that break this mold.

You may just want to forget you saw the diagram and go with Aristotle’s structure of a play: a beginning, middle, and end. Or you may want to know more about the typical sections of a play:

Exposition — This scene provides the backstory and context. An important thing to note is that exposition doesn’t have to be limited to the beginning of your play. Establish only what’s necessary to launch into the action of your play. You can fill in the rest later on.

Inciting Incident — This is the challenge that the character is thrown. It’s the starting of the clock. It’s probably the reason you wanted to write the play in the first place.

Rising Action — These are the scenes where you build your story. Characters are introduced and fully fleshed out. Conflicts are developed and allegiances revealed.

Climax — The moment after which things will never be the same. Tides turn, fortunes are won, loves are lost.

Falling Action — The conflicts and challenges in the previous scenes are confronted and resolved.

Denouement/Resolution — How things work out in the end. Is there a wedding or a funeral?

Think about what the story is that you want to tell, and which would be the best “scenes” to show.

DEVELOPING CHARACTER INTERACTION

Three things drive character interaction, known as “The Elements of Dramatic Action”:

Discovery: For example, a character finds out that he was adopted. What will he do because of it?

Revelation: A character admits that she witnessed a murder.

Decision: A character gets a divorce because her husband cannot father children.

Scenes can combine any number of these elements to move the plot forward. One character’s revelation is another’s discovery. At the same time, what the characters do with the information they receive defines their characters.

How we find out about characters? Through:

What other characters say about them

What they say about other characters

How they behave when they are alone

How they behave in the presence of others

Who they align with

A FINAL WORD ON STYLE

The action you portray on stage and the characters’ reactions determine the style, for the most part. Comedies have happy endings and witty, snappy dialogue. Tragedies have sad endings and long, combative passages of dialogue. If your characters are singing, odds are you’ve got yourself a musical. Have fun with it, and let the style evolve naturally.

Are you tackling a play for Camp NaNoWriMo this year?

Adapted from Script Frenzy’s “Intro to Playwriting” guide.

Photo by Flickr user Tom Brogan.

March 20, 2013

The Script Cabins: Writing a Graphic Novel 101

Sure, Script Frenzy may have retired, but we’ve rolled out the red carpet to the Script Cabins at Camp NaNoWriMo. This is the second of our weekly guides for all you future screenwriters, playwrights, and graphic novelists (Read our feature screenplay guide here!):

Itching to bring your very own X-Men to life? Think you’ve got the next Persepolis percolating in your brain? Well then, it’s graphic novel time! By following these simple rules, you’ll be well on your way to becoming the next Chris Ware:

Simple Guidelines to Keep In Mind

A “splash page” is a 1-panel page in a graphic novel: the art inside the panel takes up the entire page. This page is usually reserved for a big reveal or action sequence. Use these judiciously and save them for the most dramatic effect.

Most pages contain 4 - 6 panels, but you can play with this. Writing more than 8 panels per page makes it hard on the artist to properly depict images inside tiny panels.

Whenever introducing a new character, bold and CAPITALIZE that character’s name to make it easy for the artist to see. This signifies that this character is important to the story.

When creating new characters, write every detail you want the artist to convey. If you’re writing established characters, write details only if there’s a change to their appearance in that scene.

When creating your own universe, err on the side of more detail to provide your artist a fool-proof template.

The comic book medium defines the very essence of “show, don’t tell.” If you can propel your story through the art rather than expository dialogue, then do it!

Now that you have the basics laid out, time to prep for the writing of your script!

Read, Read, Then Read Some More

Genres of graphic novels range from your kid-friendly humor books to intricate, adult-targeted stories. Before you attempt to create the next Spidey, read everything you can get your hands on.

Study how many panels there are per page. How much dialogue is in each panel? How much does the art tell the story as opposed to the words? Reading the pros will inform your story-telling and open your mind to new techniques.

Respect the Artist

Comic book writing is an artist’s format above all else, so respect the fact that once you’ve finished building a skeleton, whoever is drawing it, whether it’s yourself or a partner, has to bring it to life.

Don’t fill up your script with so much exposition that the artist won’t get a chance to do what they are great at. Remember, art needs some breathing room.

Outline Your Story

I can’t stress enough how important this is. Because this is such an artist’s medium, you must know what is going to happen page-by-page, panel-by-panel, before you start to write in earnest. I can guarantee if you don’t, you will cram too many panels into one page, or you will miss your page count.

Because you are writing inside of specific space constraints, you need to have a specific idea for how each page will propel your story, and how each panel will aid in that process.

Are you tackling a graphic novel for Camp NaNoWriMo this year?

Adapted from Script Frenzy’s “Intro to Comic Books” guide.

Photo of original art by Chris Ware taken by Flickr user appelogen.be.

March 18, 2013

The Art of Writing Constantly

Do you remember how excited you were during the months leading toward National Novel Writing Month? In the days leading up to November 1, I swapped notes with friends about our characters and fought that itch to start writing early, lest I forget all my plans. During the months between NaNoWriMo and Camp, some of you may have found yourselves in the doldrums.

Last year, during NaNo Prep, we did a series called the Inspiration Diaries that talked about all the things that kept us inspired to write. But if you’re feeling as though the inspiration has dried up, I totally get you. After studying creative writing, I spent my first year and a half as a college graduate bemoaning my writer’s block, eating lots of cereal, and wondering vaguely if I’d ever get another idea again.

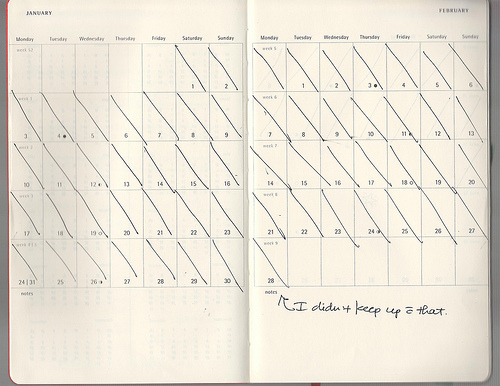

But since 2013 began, I took a page out of Tupelo Hassman’s pep talk: NaNoWriMo can be an all-year-round thing. I started the year by trying to write 3000 words a week. The number is doable (that is, I can still see daylight), but also challenging for me. But it is because of all this that I’ve found my inspiration.

When you’re in the habit of writing, everything, and I mean everything, has the potential to be fodder for a new or current project: a park where you took your niece, something witty your friend said, or a dream you had. I always relearn this when I start writing again, but it was really hammered home a few weekends ago when I was playing with my friend’s refrigerator magnets and dreamed up an entire story idea from a mere four words. Is it a good story? I don’t know. I’m having fun with it. However, two years ago, it wouldn’t have worked this way. Two years ago, my brain wasn’t in writer mode. (If you must know, it was in languish-in-a-lack-of-words mode.) Two years ago, I would have shuffled the fridge magnets around and said, “Hm that’s kinda funny,” and left it at that.

Writing every week is hard, but it’s also some crazy déjà vu. Sometimes my commitments pile up and I don’t make it. Sometimes I have to negotiate with myself. Sometimes I need a writing buddy to kick my butt and give me a hard time if I’m not writing. (Sometimes I kick my writing buddy’s butt.) Sometimes I appeal to my kick-butt writing group. But having written a novel in 30 days, I know it’s absolutely possible.

Have you been writing after NaNoWriMo?

— Ari

Photo by Flickr user Brandice Schnabel.

March 15, 2013

The Script Cabins: Writing a Feature Screenplay 101

Though we’ve retired Script Frenzy, we love our Frenziers so much that we’re hoping they’ll join us at Camp NaNoWriMo. We’ve rolled out the red carpet to the Script Cabins, including weekly guides for all you new scriptwriters hoping for some of that classic Script Frenzy wisdom:

So you’re going to write a screenplay. Awesome! You may be nervous, but don’t worry: you’re not alone. Screenwriting can feel like a mysterious art, but if you’ve ever told a story, you already have the basic knowledge needed to write a script. Just the same, we’ve put together a batch of tips that will make your first draft go more smoothly:

Start Reading Movies

Read screenplays. You can often find them online. Make sure you aren’t reading a shooting script or a transcription; you’ll know you’re looking at the wrong version if you see numbered scenes, lists of shots, or dialogue that isn’t indented.

First, try reading the screenplay for a movie you love. You’ll probably be surprised at how lean and efficient a screenplay is. Stripped of all its embellishments, the structure of the film will be easier to see. Look at how scenes relate to one another, how the dialogue flows, how obstacles are created and overcome.

Next, read a screenplay for a movie you’ve never seen before. Try to imagine the finished film in your head. Then watch the movie and see how the text was translated into a visual medium.

Choose An Idea That Excites You

Write a story that excites you, one that would be a movie you’d love to go see. Don’t worry if it’s weird, or doesn’t have a built-in audience. The best thing that you and your script can possess is passion.

Practice The Three ‘P’s: Plan, Pitch, Preview

It helps to plan the story before you begin, even if it’s in its broadest strokes:

“When a young man loses his family, he joins a group of embattled rebels and eventually brings down an evil empire.”

As long as it has a beginning, middle, and end, you’re off to a good start.

Then, pitch a 1- to 3-minute version of your plot to whoever will listen. Notice what excites them and where you lose their attention. If you find yourself saying “I dunno, then somehow this happens,” you’ll want to give those fuzzy “somehows” a little more attention.

Once you have your basic story planned, try “previewing” the trailer for your movie with your mind’s eye. What are the opening images that set the tone? How do we meet the main character? Think through the major visuals and turning points.

Get To Know Your Characters

People don’t go to the movies to see scary, romantic, or exciting situations; they go to see memorable characters reacting to scary, romantic, or exciting situations. Your goal is to create real personalities that the audience will want to watch.

You can start with a basic, 5-10 word bio of your character. Ask yourself what does this person eat, wear, and listen to? What would she die for? Kill for? How did she get to the place in her life where the film starts? Don’t forget to add flaws. Perfection is boring to watch. In fact, the best movie moments occur when a character comes face to face with his or her flaws and fears.

Give Your Story A Gazillion-Horsepower Engine

Your film has a lot of ground to cover in a short amount of time and it can’t afford to dawdle. Luckily, you can get up to speed by putting extreme situations or motivations into your script. Overwhelming desires, life-or-death obstacles, and universally potent themes can all be powerful fuel. Start looking around in your mental garage for something to build your engine with.

Put your characters in tough situations that force them to make decisions. If you’ve given them a strong enough drive, they’ll make some pretty interesting choices. If you’ve provided them with flaws and failings, they’ll have plenty of room to grow. And the audience will love being along for the ride.

Action: Write A Blueprint

A screenplay is to a film what a blueprint is to a building. All the action and description in a screenplay must translate into solidly constructed visuals. For those of you who have written prose, this translation process—and its pitfalls—can take some getting used to.

In a novel, you may write:

Sarah stands at the window, thinking about what Jeremy said in the grain silo. His face as he’d stood there nervously would always make her want to kiss him. But she couldn’t anymore. Not now, knowing he was the one who’d kidnapped the wiener dog.

The audience sees:

Sarah standing at the window, staring for a while, then frowning.

You get the point: If it’s internal dialogue, memory or anything else that goes on inside someone’s head, it isn’t going to end up on screen unless it’s translated into an image or dialogue.

Dialogue: Don’t Let it Slow You Down

Writing great dialogue is a precision art form. While tackling your first draft, don’t let dialogue slow you down. When you can’t think of the perfect rejoinder, write filler and then spice it up on the next draft. Your best lines will often come to you later.

Still, as you get prepare to tackle your script, there’s no harm in polishing up your skills. The best way to learn how to write dialogue is to listen to how real people talk. Become a linguistic anthropologist, and carry a pocket notebook with you—real-life exchanges are worth their weight in gold. Use them as inspiration to write snappier, plot-driving dialogue.

Finally, remember: you’ll have plenty of time to be miserably stressed once the studios hire you to write blockbusters for hundreds of thousands of dollars. For now, savor the creative freedom and freefall into your story.

Adapted from Script Frenzy’s “Intro to Screenwriting” guide.

Photo by Flickr user pietroizzo.

Welcome to the Script Cabins: Writing a Feature Screenplay 101

Though we’ve retired Script Frenzy, we love our Frenziers so much that we’re hoping they’ll join us at Camp NaNoWriMo. We’ve rolled out the red carpet to the Script Cabins, including weekly guides for all you new scriptwriters hoping for some of that classic Script Frenzy wisdom:

So you’re going to write a screenplay. Awesome! You may be nervous, but don’t worry: you’re not alone. Screenwriting can feel like a mysterious art, but if you’ve ever told a story, you already have the basic knowledge needed to write a script. Just the same, we’ve put together a batch of tips that will make your first draft go more smoothly:

Start Reading Movies

Read screenplays. You can often find them online. Make sure you aren’t reading a shooting script or a transcription; you’ll know you’re looking at the wrong version if you see numbered scenes, lists of shots, or dialogue that isn’t indented.

First, try reading the screenplay for a movie you love. You’ll probably be surprised at how lean and efficient a screenplay is. Stripped of all its embellishments, the structure of the film will be easier to see. Look at how scenes relate to one another, how the dialogue flows, how obstacles are created and overcome.

Next, read a screenplay for a movie you’ve never seen before. Try to imagine the finished film in your head. Then watch the movie and see how the text was translated into a visual medium.

Choose An Idea That Excites You

Write a story that excites you, one that would be a movie you’d love to go see. Don’t worry if it’s weird, or doesn’t have a built-in audience. The best thing that you and your script can possess is passion.

Practice The Three ‘P’s: Plan, Pitch, Preview

It helps to plan the story before you begin, even if it’s in its broadest strokes:

“When a young man loses his family, he joins a group of embattled rebels and eventually brings down an evil empire.”

As long as it has a beginning, middle, and end, you’re off to a good start.

Then, pitch a 1- to 3-minute version of your plot to whoever will listen. Notice what excites them and where you lose their attention. If you find yourself saying “I dunno, then somehow this happens,” you’ll want to give those fuzzy “somehows” a little more attention.

Once you have your basic story planned, try “previewing” the trailer for your movie with your mind’s eye. What are the opening images that set the tone? How do we meet the main character? Think through the major visuals and turning points.

Get To Know Your Characters

People don’t go to the movies to see scary, romantic, or exciting situations; they go to see memorable characters reacting to scary, romantic, or exciting situations. Your goal is to create real personalities that the audience will want to watch.

You can start with a basic, 5-10 word bio of your character. Ask yourself what does this person eat, wear, and listen to? What would she die for? Kill for? How did she get to the place in her life where the film starts? Don’t forget to add flaws. Perfection is boring to watch. In fact, the best movie moments occur when a character comes face to face with his or her flaws and fears.

Give Your Story A Gazillion-Horsepower Engine

Your film has a lot of ground to cover in a short amount of time and it can’t afford to dawdle. Luckily, you can get up to speed by putting extreme situations or motivations into your script. Overwhelming desires, life-or-death obstacles, and universally potent themes can all be powerful fuel. Start looking around in your mental garage for something to build your engine with.

Put your characters in tough situations that force them to make decisions. If you’ve given them a strong enough drive, they’ll make some pretty interesting choices. If you’ve provided them with flaws and failings, they’ll have plenty of room to grow. And the audience will love being along for the ride.

Action: Write A Blueprint

A screenplay is to a film what a blueprint is to a building. All the action and description in a screenplay must translate into solidly constructed visuals. For those of you who have written prose, this translation process—and its pitfalls—can take some getting used to.

In a novel, you may write:

Sarah stands at the window, thinking about what Jeremy said in the grain silo. His face as he’d stood there nervously would always make her want to kiss him. But she couldn’t anymore. Not now, knowing he was the one who’d kidnapped the wiener dog.

The audience sees:

Sarah standing at the window, staring for a while, then frowning.

You get the point: If it’s internal dialogue, memory or anything else that goes on inside someone’s head, it isn’t going to end up on screen unless it’s translated into an image or dialogue.

Dialogue: Don’t Let it Slow You Down

Writing great dialogue is a precision art form. While tackling your first draft, don’t let dialogue slow you down. When you can’t think of the perfect rejoinder, write filler and then spice it up on the next draft. Your best lines will often come to you later.

Still, as you get prepare to tackle your script, there’s no harm in polishing up your skills. The best way to learn how to write dialogue is to listen to how real people talk. Become a linguistic anthropologist, and carry a pocket notebook with you—real-life exchanges are worth their weight in gold. Use them as inspiration to write snappier, plot-driving dialogue.

Finally, remember: you’ll have plenty of time to be miserably stressed once the studios hire you to write blockbusters for hundreds of thousands of dollars. For now, savor the creative freedom and freefall into your story.

Adapted from Script Frenzy’s “Intro to Screenwriting” guide.

Photo by Flickr user pietroizzo.

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers