Chris Baty's Blog, page 168

March 24, 2015

Choose Your Camp: Welcome to the Party Cabin

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Stacy McAnulty author of the picture book, Dear Santasaurus, shares why Camp Plot is home to the party cabin:

Sure Camp Character probably has some interesting folk, both real and fictional. And the campers at Camp Setting can probably paint a beautiful sunrise or magical worlds. Me, I’m all about Camp Plot. During a first draft, a plot cabin is the party cabin.

When you come to Camp Plot, don’t worry about getting caught doing the wrong thing. This is the time to take a chance. Here, you get to kiss the hot guy, skinny dip, have another drink, or debate which Comedy Central show is the best. That means in your first draft, you get to kill off characters, have crazy love affairs, introduce an insane butter-knife-wielding psycho, debate (and win) whatever argument you’d like. Wahoo! Go crazy. We are here to party.

Now, when you went to these parties in high school, hopefully, you didn’t pee on the furniture. You didn’t jump off the roof into a kiddie pool. You showed some restraint. We need a teeny tiny guiding voice while writing. Not much. Authors rarely die in the Plot Cabin. So if you are seventy-five percent through your historical romance, don’t send in an alien ship to whisk away the hero just because you can’t think of a legitimate reason for him to run from Francesca. Stay off the roof! Come back in the cabin and have another drink.

Camp Plot doesn’t have to be completely void of structure. When you went to that high school party, there were established rules for beer pong or other merriment. Let’s think of each scene in our novel as a game. Here are simple, fun rules for The Scene Game. In each scene, the main character must want something, and you get to decide if she gets what she wants or if she is denied. So don’t just send your character to work in the morning. Send him there to confront his boss. Or to hit on her assistant. Or to win the big case. Or to set the place on fire.

And you get to decide if the hero is successful or not. You have all the power. How cool is that?

String sixty to eighty of these scenes together and you suddenly have a novel. Wasn’t that fun and easy? The sad part is, once this is done, you must leave the party cabin… I mean, Plot Cabin. You don’t want to be that 23-year-old hanging out with the high school kids. (You know they only like you because you can buy beer.)

In second drafts and beyond, you are no longer at this easy-going camp. You are on an Appalachian-Trail type journey, alone with your thoughts. Your body will ache, you’ll question everything, and you’ll be afraid. (On the trail you’d be afraid of bears or snakes or crazy people. During revision, you’re afraid of never getting the plot right.)

But let’s not even think of revision now. That’s a problem for future you. And if you write all your scenes chockfull of conflicting desires, how bad can it be? Now, I invite you into the Plot Cabin where the good times roll and the rules are few. May your Solo cup overflow with amazing scenes.

Stacy McAnulty writes for children and teens. Her chapter book series, The Dino Files, will hit shelves in January 2016. Her picture book, Dear Santasaurus, is available now. She has eight picture books releasing in 2016 and 2017 including Excellent Ed and Beautiful. When not writing, Stacy spends her time thinking about writing, “researching” on the internet, reading, or eating. She has survived—um, won!—NaNoWriMo three times. She lives in North Carolina with her three kids, two dogs, one husband, and zero dinosaurs.

Top photo background by Flickr user Shutter Fotos.

March 20, 2015

Choose Your Camp: 5 Ways to Bring Place and Time Alive

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Krista Van Dolzer, author of The Sound of Life and Everything and Don’t Vote for Me, makes the final case for Camp Setting… and just why time and place can be so crucial:

When you list the elements that every story has to have, setting is probably the last one on your list. But just because setting doesn’t feel like the most important element doesn’t mean it’s not important. An intriguing setting can tip a book from good to great.

Now, I’m a reader who skims over lengthy paragraphs of description and a writer whose first drafts are more like a skeleton than a living, breathing thing. Still, I’ve come to appreciate a well-crafted setting, which includes both place and time.

PlaceYou have to set your story somewhere, but the best writers set their stories purposefully, then let those settings become characters in their own right. Stephanie Perkins’s Anna and the French Kiss would have been a lot less intoxicating if it had been Anna and the Milwaukee Kiss. (Not that I have anything against Milwaukee! It’s just not as magical as Paris.)

And the world in Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson’s Wheel of Time series was so richly drawn that, by the time I finished, I felt as if I’d actually been to Tar Valon and Bandar Eban.

TimeSome stories come with built-in eras—for obvious reasons, Elizabeth Wein’s Code Name Verity and Anne Blankman’s Prisoner of Night and Fog had to be set during or just before World War II—but other stories allow more freedom.

The early Victorian era definitely added to the creepiness of Jonathan Auxier’s The Night Gardener while Beth Kephart’s Small Damages made use of an ambiguous time period to give her contemporary story a sense of timelessness. (For the record, Small Damages

, which is set on a bull ranch in southern Spain, is also an excellent example of place.)

Last but not least, a few tips to send you on your way:

Include sensory details to breathe life into your setting. What does the dock sound like? What does a busy street smell like?Every time you go back to a location, make sure to up the ante. School stories, for instance, are going to reuse locations, so every time your characters go back to, say, the cafeteria, give them something new to do.Use specific words to build your world. If your book is set in Utah, don’t call it a soda when you could call it a pop (and if your book is set in Alabama, don’t call it a pop when you could call it a coke). Similarly, if your book is set in 1893, don’t call it a bathroom when you could call it a water closet.Research, research, research. Even if you’re building a new world, rooting it in something real—like an ancient empire or a twenty-first-century metropolis—will give your made-up world more weight.Know your world so well that, for every detail you include, there are four or five more details you could have included but chose not to. You can’t know which details are most important unless you know some of the ones that aren’t.Now get in there and nail your setting!

Krista Van Dolzer is a stay-at-home mom by day and a children’s author by bedtime. She lives with her husband and three kids in Mesquite, Nevada, where she watches too much college football and looks for her dead people online. She’s the author of

The Sound of Life and Everything

(G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers, May 2015) and

Don’t Vote for Me

(Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, August 2015).

Top photo background by Flickr user A Walker in LA.

March 18, 2015

Choose Your Camp: How Setting Can Reinvent Your Story

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Nicola Yoon and David Yoon, author and illustrator respectively of the forthcoming book, Everything, Everything, share how setting can act as a minor god:

It’s often said that setting acts as character in a story: it’s true that settings can have their own personalities and moods like people, but a setting can also do many things people can not. I like to think of settings as omniscient and powerful minor gods with near-total control over your protagonist and plot. A setting can mirror the mindset of your heroine, or it can fight against her wishes. It can let her hide away or force her to reveal her true self before she’s ready. A setting can be your heroine’s best friend or worst enemy or both—sometimes in the blink of an eye…

A great example of setting is in Dave Eggers’ A Hologram for the King, which is a Waiting for Godot-like tale about an American tech salesman lost in Saudi Arabia. Eggers presents the desert as both a blank canvas full of potential as well as an unfamiliar world full of alienation, and indeed his hero vacillates between feelings of self-reinvention and total impotence. Many of the scenes take place on construction sites, not only mirroring the hero’s own incompleteness but also providing the character various plot possibilities to get entangled in.

Settings help drive the plot and character. Sometimes I use the fish-out-of-water approach, placing a character in a setting she would never normally be in to see what choices she makes. Other times I place a character in her favorite setting, like a calm and relaxing ocean on a summer day. Then, I turn the setting against her to see how she reacts to the sudden betrayal as that same soothing ocean churns, becoming indifferent and deadly.

One of my favorite ways to use setting is as a setup for things to come, things I don’t want to belabor through excessive expository dialogue or plot. A young couple enters a much too small hotel room with a comically large bed, for example. Their new love for each other and the physical possibilities that come with it are all reflected in this room without either of them having to say a thing.

Finally, a setting cannot simply be. At the very least it must do the job of ostranenie, or of making ordinary things seem strange and new. Imagine how a parking lot would look to a baby, or a newly arrived extra-terrestrial. In my case for my book—Everything, Everything—I had to imagine how the world would look to a girl who’d never left her house in all of her seventeen years: freeway traffic, wind, flowers.

The world is filled with all kinds of beauty—pleasing, ugly, unconformable and conflicting. There’s a thrill that comes with seeing the mundane reinvented into something exotic on the page. It’s our job as writers to keep our readers enthralled. Setting can help us do that.

Nicola Yoon grew up in Jamaica (the island) and Brooklyn (part of Long Island). She currently resides in Los Angeles, CA with her husband and their daughter, both of whom she loves beyond all reason. Her first novel, Everything, Everything , will be published by Random House Children’s Books on September 1, 2015. Follow her on Twitter\Tumblr: @NicolaYoon

David Yoon is a writer and designer. He lives with his wife Nicola Yoon in Los Angeles, CA, where they spend their days talking about stories and reading (many, many) books to their 3-year-old daughter. David created the illustrations for Everything, Everything.

Top photo background by Flickr user BLMOregon.

March 17, 2015

Choose Your Camp: 3 Ways to Transport Your Reader

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, Mónica Bustamante Wagner, author of the forthcoming series, Frosh, offers her method of transporting readers to another reality:

Can you imagine Anna and the French Kiss set in a small, rural town? Or Harry Potter going to school somewhere in the Sahara Desert? There’s nothing wrong, obviously, about setting your book in a small town or the Sahara Desert, but I think it’s amazing how much identity the setting can give to a book. This is why I chose the Setting Cabin. I feel sometimes we writers take settings for granted, and they could use some love today…

When we read, we usually want to be transported to another place and learn about other realities. So I think it’s important to make the reader feel they’re already in that place. Apart from using vivid and original sensory details, it’s nice to show emotion when the characters experience these places. It’s awesome how much you can learn about a character when you see things under their perspectives. (Okay, I swear, I’m not about to jump to the Character Cabin—I’m just sayin’.)

Anyway. An example: Jack and Nina go to the same garden, and from Jack’s POV the garden could be described:

“Itchy grass covered The Royal Garden, and the stupid lilies were shedding their pollen, making me sneeze non-stop. It didn’t help that the rows of flowers were half a mile long. The sun was high in the sky and I was sure that if I didn’t run to take cover under the ant-infested trees, I’d leave grandma’s picnic with a horrible sunburn.”

But from Nina’s POV it could be written:

“The Royal Garden was half a mile of bliss. Rows and rows of flowers bloomed under a warm sun, and the grass felt soft and dewy under my feet. Birds chirped over the lush canopies, beckoning me to stay here forever.”

Also, it’s nice to show the setting instead of telling us about it. For example: instead of saying

“The waves were big and dangerous,”

You can say something like,

“The waves swelled, towering over the fishermen’s ships, crashing and exploding against the pier.”

And don’t forget to ground your readers early in the scene. For instance, imagine you’re reading a chapter that starts when Paul decides he’s finally going to kiss Mary! They’re talking about something oh-so-romantic, and if the author hasn’t grounded you, you’ll probably start to picture things on your own.

What would I imagine in a scene like this? My brain would go to my concept of romantic places. I’d think they’re in a restaurant, at night, and their table is illuminated by a candle… But then! The author writes something like, “Paul opened his locker and grabbed a textbook.”

Then I would be like, What? But, but, but I had imagined they were in a restaurant! So I would feel lost, and like I’m not part of that love story anymore. Makes sense?

Summing up:

Make the readers feel like they are where your characters are. Use sensory details and show emotion.Try to show the setting instead of telling us about it.

Ground the reader early in a scene.

Mónica Bustamante Wagner was born in a Peruvian city by a snow-capped volcano. Growing up, books were her constant companion as she traveled with her family to places like India (where she became a vegetarian), Thailand (where she almost met Leonardo di Caprio), France (where she pretended to learn French), and countless other places that inspired her to write. She’s the author of the forthcoming NA trilogy, Frosh (The Studio/Paper Lantern Lit, Fall 2015) and is represented by @Lauren_MacLeod.

Top photo background by Flickr user Leah Borchert.

March 13, 2015

Choose Your Camp: How to Make Your Setting Breathe

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, Renée Ahdieh, author of the forthcoming The Wrath and the Dawn, shares how to make your setting a breathing character of its own:

There are many important aspects to creating a wonderful narrative. Character and plot are, of course, absolute necessities. Without a cohesive story to tell or people to live the tale, any novel would be a tough sell.

But an often overlooked aspect of a book is its setting. After all, another word for this is “background.” By its very nature, it’s meant to set the stage. To fade into the distance and never, ever overtake its counterparts.

I chose the Setting Cabin because I often make a character out of setting, and I think it should be a just as big an element of a novel as character or plot. To me, setting helps to establish voice just as much as a character’s backstory. It’s a chance to add color to a world, and sparkle to something that might come off as ordinary otherwise.

After I create character profiles and establish a plot arc, I often spend a great deal of time establishing setting. Since I write fantasy, this entails a good bit of research and world building—aspects of the process I greatly enjoy. When undertaking this endeavor, I typically turn to other novels and resource materials written about a particular time period, but I will also read poetry and other forms of prose to help me along the way.

I also think it’s of tantamount importance to appreciate other books that handle setting well. Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles always come to mind in these instances. She makes New Orleans writhe and seethe with an undercurrent of dangerous sensuality all its own. Isabel Allende and Diana Gabaldon are two other writers who go to great lengths to make characters out of their settings. In young adult, I adore Libba Bray and Leigh Bardugo for their lush depictions of their respective worlds. Bray’s A Great and Terrible Beauty has always been a personal favorite for this very reason.

If you’re struggling to find a means to impart more aspects of setting into your work, I would begin with the senses first. It’s the most natural and unobtrusive way to introduce setting into your writing. Always shy away from lists whenever possible.

See if you can impart a sensory facet into a character’s action. Maybe your main character doesn’t merely take a sharp breath. Maybe your main character can take a sharp breath of the sooty London air. In these ways, you can bring your setting to life as you bring your character into being.

And your reader will be right there with you at every moment.

Renée Ahdieh is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In her spare time, she likes to dance salsa and collect shoes. She is passionate about all kinds of curry, rescue dogs, and college basketball. She lives in Charlotte, North Carolina, with her husband and their tiny overlord of a dog. Her debut The Wrath and the Dawn will be available from Penguin/Putnam on May 12, 2015.

Top photo background by Flickr user Christian Mountain-Hawk.

March 11, 2015

Choose Your Camp: Why Characters Are Your Story Core

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, Sharon Cullen, Wrimo and author of His Saving Grace, shares a final argument for Camp Character:

When I was told I had to pick a camp, it was a no-brainer for me. Camp Character all the way, baby! I didn’t even have to think about it. In my mind characters are the driving force behind any timeless story. I don’t care what genre or what time period we’re talking about, it’s the characters we connect with.

When I was trying to decide what to write about I started thinking of my favorite movies. I picked a few and tried to place them in different settings and time periods. You know what? Setting didn’t matter. Time period didn’t matter…

Let’s take The Breakfast Club as one example. The movie is about high school kids forced to spend a Saturday together in detention. There’s the brain, the punk, the princess, the athlete and the psycho—all different stereotypes, taken out of their comfort zones and friendship circles, forced to face their own prejudices and beliefs. And they discover they all have more in common than they thought.

What if you took those characters and placed them in today’s high schools? Or you took similar characters with similar backgrounds and forced them together in a historical novel?

The story wouldn’t change at its core because it’s about the characters’ journeys—the characters’ thoughts and feelings, their paths to self discovery.

Let’s try a different movie. Grease. An oldie but a goodie. It was filmed in the ‘70s but takes place in the ‘50s. The story is about Danny, a leather wearing hood, and Sandy, a goody two shoes girl. Both from different social spectrums and completely different backgrounds. They like each other but it’s not “cool” for them to like each other.

What if that movie took place now? Oh, wait. It did in the ‘80s with Pretty in Pink. What if that movie took place in a historical time period? Oh, wait. Romeo and Juliet.

These story types are timeless because of the characters. Because you identify with the characters’ dilemma—their forbidden love. You root for them to get together because you love the characters.

Characters are who we, as readers, connect to. You can have a brilliant plot, you can create a diverse, wonderful world to put your characters in, but if your reader can’t connect to your characters, then the story is lost.

When I first started writing I knew I wanted to write emotionally packed stories. I wanted my readers to cry and laugh with my characters. That can’t happen if you don’t have a character that a reader can connect to.

My latest release (written as a NaNoWriMo novel in 2013 and published in 2014) is about a hero with a brain injury acquired in the Crimean War. The story obviously takes place in 19th century Victorian England but it’s a story that could easily take place in the 21st century because it’s about characters fighting to find a new normal after such a devastating injury.

Without characters you have no story.

So Camp Character wins, right?

Sharon Cullen is published in historical romance, romantic suspense, paranormal romance and contemporary romance. Her 2013 NaNoWriMo novel, His Saving Grace, was published in December 2014 and her 2014 NaNoWriMo novel, Sutherland’s Secret, will be published in 2016. She lives in southwest Ohio with her brood although her dream is to someday retire to St. Maarten and live on the beach.

Top photo background by Flickr user ettiz.

March 9, 2015

Choose Your Camp: Practicing Empathy for Your Characters

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, W. C. Bauers, author of Unbreakable, shares why writing characters is all about listening:

I’m drawn to character-driven narratives so bunking at Camp Character was the obvious choice. Besides, the campers in Plot wouldn’t stop playing Elvis’s “A Little Less Conversation (A Little More Action Please)”. I walked in, heard that, and turned around.

Then I headed toward Setting. As I approached the cabin a few campers saw me rubbing my hands together for warmth and waved me over to the fire. But they wouldn’t stop stoking the flames with adverbs. It was a lovely fire, but the crackle of “lys” was overwhelming.

Character is irreducibly complex. The build-a-bear method of developing character sounds promising enough, but it never worked for me. Writing character is less about assembling a list of traits about your protagonist, and more about going on a journey with her, getting inside her head, and listening to her before writing about her. Perhaps most of all it’s about practicing empathy.

When I first sat down to write Unbreakable, all I had was my main character, Promise. She’d just come of age. She was thinking about her future and what she might become. Then raiders hit her home world and murdered her father. Because she’d lost her mother years before and had no other family to speak of, Promise didn’t know what to do. She was traumatized and angry. She came to me looking for an out. I wanted to tell her story.

Unbreakable started that way. Me listening; Promise speaking. She told me she was tired of living like this and that she didn’t think she could go on. I suggested she join the Marines, get off-planet and see the ‘verse, and live life on her own terms.

I’m leery of methods or proscriptive approaches to writing characters. I just don’t think a one-size-fits-all works. Writing a synopsis is straightforward enough: start at A and by the end of the novel your protagonist better be at Z or she’s in a world of hurt, and you as a writer have an unfinished, unsaleable book.

Writing an engaging character is altogether different, even counterintuitive. It’s a process of discovery. My agent gave me some wonderful advice about this, really the best I’ve heard on the subject. She told me to write my first draft to get to know my characters. Then, go back and revise with the benefit of hindsight.

Characters are like real people. They grow and change. I had to take that into account as I edited Unbreakable and prepared it for outside eyes.

I’d also recommend practicing self-doubt as you write dialogue. We all know the saying about showing verses telling. Good writers show while they tell—at least that’s what I’m striving for—and they don’t blindly tell their characters what to do, what to say, or how to say it. Rather, they let their characters speak for themselves.

Character is voice. As I wrote Unbreakable, I kept asking myself if Promise would say this or that. Would she say it with different words, or a different tone of voice? How? The last thing I wanted to do was put words into her mouth and trample her unique voice.

W. C. Bauers’s interests include Taekwondo, military history, and French-press brewing. He lives in the Rocky Mountains with his wife and three boys.

Unbreakable

is his first novel.

Top photo by Flickr user WherezJeff.

March 6, 2015

Choose Your Camp: The Fine Line of Iconic Characters

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, Christina Dalcher, author and Wrimo, shares how she learned to walk the tightrope of realistic, yet quirky characters:

Now is the time to confess: I’m head over heels in love with another man.

His name? Jack Reacher.

I don’t actually want to date the guy. But man, that character. The loner with the noblesse-oblige complex, the no-phone-no-suitcase-no-attachments idiosyncrasies, the mathematical obsessions. Reacher is at once Everyman and No Man, and his creator, Lee Child, got it all right when he made this character.

Are Child’s plots interesting? Yes. Are his settings unique? Sometimes—it depends what you think of as unique. Plenty of Reacher’s adventures happen in small-town Anywheresville, USA. What stands out in every single book, literally heads above the rest, is that six-and-a-half-foot-tall man who won’t take nonsense from anyone.

Reacher, wonderful as he is, has serious competition from the woman who lives in my head: Dr. Daniela (Danny) Jones. She’s my main girl and my favorite character. Why? Because Danny’s got exactly that: character…

She’s tough and clever, cynical with a soft side, and resourceful as all get out. Danny’s a linguist, a former FBI Special Agent trainee, a waitress, and an orphan. Sometimes I’m kind to her. Other times, I put her in nasty situations. (That’s okay—I built Danny to be able to get out of them mostly unscathed.)

Wherever I take her and whatever happens, I know my girl will be the center of the story.

Whether I’m reading or writing, it’s all about character. You can come up with an intricate plot and most out-of-this-world world, and still fail. How? By not creating a character your readers want to root for.

Imagine, if you will, the following scenarios from well-known novels:

Oliver Twist:

Fagan is a kindly old soul who loves helping young orphans.

The Silence of the Lambs:

Clarisse Starling is a seasoned FBI agent with no fears or emotional baggage.

See what I mean? I’ve just taken iconic characters and made them un-iconic. Normal. Boring.

Before I start writing, before I consider what’s going to happen where, I think about who stuff is going to happen to.

Do I struggle? Sure. Mostly because I worry about being heavy-handed with characters. I want to give them eccentricities and habits and layers; I want to make them strong and larger-than-life. But doing that without alienating a reader by creating someone too quirky or super-human requires some amount of literary tightrope walking. Tip over too far in one direction, and both you and your character will fall flat. Remember:

Get physical, but don’t overdo it

Readers want a sense of what your story people look like, but that doesn’t mean you need to hit them over the head with every detail down to the length of your character’s eyelashes. Sketch in broad strokes, and leave some to the imagination.

Give them background without an info dump

Your characters’ experiences make them complete people and motivate choices and actions. So give us some clues from the past. Was your MC the last person picked for the gym class team? Did she fall head over heels in love and have her heart rent in two? Has he committed a past crime? Tell us—just not all at once.

Flaws aren’t just for real people (or Oedipus)

Bring the people in your story to life by making them real. Give them a few hang-ups, a neurosis (or two), maybe a bit of a dark side. You don’t need to go overboard with flaws fit for a Greek tragedy, but if your MC is a wee bit screwed up, readers will relate.

Make them memorable

Whether they’re pleasingly plump or wasp-waisted, have a bizarre preference for drinking gin and grapefruit juice, never learned how to drive a car, or speak five languages fluently—it’s your choice! Dive into your imaginary junk pile of quirks and grab some to turn those characters into people your readers won’t easily forget.

Christina Dalcher, Ph.D. (@CVDalcher) is a theoretical linguist specializing in phonetics and phonology. Her research has covered the physical, cognitive, and social forces contributing to sound change in Italian and British English dialects. Christina’s first novel Lucky Thirteen—an adult thriller featuring (you guessed it!) a linguist—is represented by Alec Shane of Writers House.

Top photo by Flickr user blavandmaster.

March 4, 2015

Choose Your Camp: 3 Tips for Creating Indelible Characters

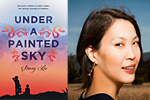

Camp NaNoWriMo begins in April! In the spirit of friendly camp competition (and inspired by one of our favorite scenes in Scott Westerfeld’s Afterworlds), we asked our friends to Choose Your Camp. Today, Stacey Lee, author of the soon-to-be-released Under a Painted Sky shares why she’s a champion of Camp Character, and how she creates strong characters:

For me, characters are the key to making stories memorable. We measure characters against ourselves. Egocentric creatures that we are, the more something relates to our lives, the more we remember it.

I haven’t the foggiest idea what happens in Jerry Maguire, but I do remember the determined sports agent yelling “Show me the money!”

I read The Hobbit twice, but still can’t tell you what happens beyond orcs chasing hobbits. However, the good-natured and loyal Bilbo Baggins, and the irritable yet charming Gandalf are indelibly inked on my heart.

Some people like to divide books into two categories: those that are character-driven, and those that are driven by plot. But to be compelling, even a plot-driven story requires well-drawn characters (just as a character-driven story still requires a plot). So let’s talk about how to create a strong character. Here are my three down and dirty tips:

Steal.

If you don’t already have a character in your head, I highly advise stealing one. There are nearly seven billion people in the world, and surely, one of them can serve as the basis for your character.

Maggie Stiefvater said, “I steal a human heart for each of my characters. I might wrap them in a very different set of details than that real-life model, but they all start as someone real.”

Watch the news, eavesdrop on the people at Trader Joe’s, go to all the parties. Your characters are out there, waiting to be discovered.

Take a personality test.

The internet is full of personality tests. You can sort yourself into Hogwarts houses, or find out which ’80s star is most likely to play you in the Lifetime movie of your life.

Use the tests to find out about your character. Or use them to find out about yourself, which can sometimes be the same thing. Just don’t send it to all your Facebook friends because that is how productivity stops in the world of writers.

Make them imperfect.

While virtues may be admirable, weaknesses are relatable, and relatable means memorable. Weak spots can be physical (Crane-man’s shriveled leg in A Single Shard, Piggy’s nearsightedness in The Lord of the Flies), or mental (Tom Riddle’s fear of dying in the Harry Potter series, Jo March’s hot temper in Little Women).

I recently read a book debuting later this year called The Sacred Lies of Minnow Bly by Stephanie Oakes where the main character is missing her hands. Why give your characters these flaws? They’re an opportunity to dig deeper. How has that prosthetic leg affected Augustus? Is it something he’s self-conscious about? And why the heck is Minnow missing her hands? This is backstory we want to know.

As a last point, I want to mention character arcs, a topic that requires a post of its own. Once you have defined your characters, you must use your plot to help them grow. Not all growth is transformative, and sometimes, a character’s growth is simply to remain steadfast. Now go forth, and create your army!

Stacey Lee is a fourth generation Chinese-American whose people came to California during the heydays of the cowboys. She believes she still has a bit of cowboy dust in her soul. A native of southern California, she graduated from UCLA then got her law degree at UC Davis King Hall. After practicing law in the Silicon Valley for several years, she finally took up the pen because she wanted the perks of being able to nap during the day, and it was easier than moving to Spain. She plays classical piano, wrangles children, and writes YA fiction.

Top photo background by Flickr user frix.cz.

March 2, 2015

The "Now What?" Months 2015: A Compendium

Every year, during the “Now What?” Months of January and February, we dive deep into the worlds of editing, revision, and publishing.

Need a round-up before you move onto your next project? (Camp NaNoWriMo is coming up…) You’re in luck:

A Chat With J. K. Rowling’s Acquiring EditorEnchanting an Editor — Barry Cunningham and M. Anjelais

A Huddle with the Agents of New Leaf Literary#NaNoNewLeaf 2015 — New Leaf Literary, compiled by Lauren Simonis

On Tackling Revision, One Step at a Time When to Trust Your Gut — Laurie Weed3 Questions to Ask as You Cut Your Manuscript — Sarah Ahiers Why Revision Is a Multi-Step Process — Lexie Dunne Finishing Your NaNo-novel No Matter What — Grant Faulkner 3 Steps to Turn Your Manuscript from Monster to Masterpiece — Kitty Burroughs5 Authors Who Polished & Published their NaNo-Novels Why the Most Important Thing About Your Novel Isn’t the Words — Robin Stevens Discovering Character and Theme Through Revision — Jason W. LaPier

Start Revision at the Beginning — Lauren Gibaldi

Finding the “Right Story” In Your Draft — Susan Dennard Polishing an Incomplete First Draft — Jason Hough

On Knowing When Your Novel Is Ready for Its Close-up Everything You Need to Publish a Novel — Chris Angotti 5 Times to Say Yes — Heather Lazare

5 Questions to Ask About Your Manuscript — Lindsay Edgecombe

How to Find a Great Reader… and What to Ask Them — Cal ArmisteadOn the Process of Finding an Audience for Your Masterwork 5 Tips for Launching Your Book — Lauren HarsmaSubmitting Your Manuscript: A To-do List — Samantha Streger 7 Things Publishing Pros Wish You Knew — Holly West How to Query Better — Danielle Barthel and Jaida Temperly

How the Relationship Between an Author and an Editor Is Different than You Might Think — Michelle Krys and Wendy Loggia

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers