Chris Baty's Blog, page 140

September 2, 2016

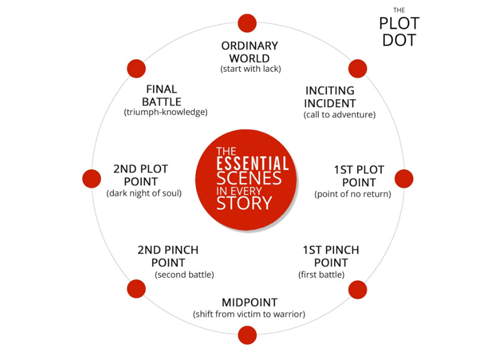

Plot Doctoring: 9 Steps to Build a Strong Plot

Like the main event itself, NaNo Prep is always better with an incredible writing community around you. Luckily, our forums come with such a ready-made community. Inspired by the Plot Doctoring forum, we asked Derek Murphy, NaNoWriMo participant, to share his thoughts on plotting, and he outlined his 9-step plotting diagram:

Here’s a truth: you must write badly before you can write well.

Everybody’s first draft is rubbish. It’s part of the process, so don’t worry about it. The writing can be polished and fixed and improved later, after NaNoWriMo, during the editing stages.

What most writers get out of NaNoWriMo is a collection of great scenes that don’t necessarily fit into a cohesive story—and that’s a problem if you want to produce something publishable.

Nearly all fiction follows some version of the classical hero’s journey: a character has an experience, learns something, and is consequently improved. There are turning points and scenes that need to be included in your story—if they are missing it won’t connect with readers in an emotionally powerful way. And it’s a thousand times easier to map them out before you write your book.

A little bit of plotting before you start to write will remove 95% of the hesitation and writer’s block that causes most people to give up on

NaNoWriMo

because their story “isn’t going anywhere” or they “don’t know what to write next.”

Personally, I had dozens of aborted fiction projects but could never get through to the end of one until I took the time to map it all out, scene by scene. Getting my PhD in Literature helped a little, but it was ultimately the plotting worksheets, maps, and diagrams I downloaded that helped me the most. But they weren’t perfect for me, so I made one of my own.

1. We start with the ordinary worldYour First Act sets up your main character (MC) in their ordinary, mundane environment. You’ll introduce their friends and family members, their home, school, or workplace.

But you also need to show what’s missing. You don’t want to start with a perfect, happy character who has everything (unless you’re going to take it all away, which is fine). You need to give them space to grow. Maybe they have unresolved emotional issues. They’re probably shy, awkward, clumsy or embarrassed, or unpopular. Maybe they hate their job or just got dumped.

You need to show what they want, their secret desires. What are they working towards? They probably have daydreams about things they don’t think will ever happen.

2. Inciting incident—the call to adventureIn most books, the inciting incident should actually happen in chapter one or two. It’s an intrusion on the ordinary world. Something big changes. Maybe a stranger moves to town, or a family member dies, or there’s an earthquake. It might be an invitation, or a friend asking your MC to a party. It can’t be a huge crisis, but it will be annoying and noticeable, or exciting—it’s the beginning of your plot. That’s why you want to get the ball rolling pretty early, otherwise nothing will be happening.

Avoid writing a lot of history or backstory. Start your book as near to the inciting incident as you can. But don’t think of it as just one scene or chapter. The “call to adventure” is usually followed by denial or refusal. The MC doesn’t trust it, or doesn’t want to make a decision. They’ll ignore it and continue focusing on their previous goals. They just want things to go back to normal.

3. First plot point—the point of no returnThings have been getting weirder and/or more intriguing for several chapters. Your MC tries to ignore the problems but they keep interfering with their normal agenda. They get roped in, and something happens that forces them into the action. Everything changes, and there’s no going back to the ordinary world.

They might have met a teacher, or they might have seen something that changes their perspective: a revelation of supernatural abilities; a murder or death; an accident, or robbery, or attack, or disaster. Something pretty big, that shatters what they thought they understood of the world, and makes them feel vulnerable and exposed.

This will be one of the major scenes in your book, so make it unforgettable. Also, this is the end of Act One, about 25% of your book—by now all the major characters should have already been introduced, or at least hinted at.

4. First pinch point—the first battleAfter the first plot point, there will be several chapters where the protagonist is learning about the new world. They might be doing research, or discovering things in conversations. There needs to be conflict and tension, which builds up to the first Pinch Point.

This doesn’t have to be a literal battle, but it is the first major interaction with the antagonist. The antagonist might not be visible yet, but they should be the one pulling the strings. The antagonist is after something, and that something is tied to the MC somehow.

Maybe the antagonist wants something the MC has, or needs the MC to do something, or has a score to settle. The MC probably still has no idea what’s happening, but they find themselves at the center of some conflict. They probably don’t win, but they do survive.

Now the stakes are clear. You should make them as dire as possible, almost inconceivable. Ask yourself, “What’s the worst thing that could happen?” Then ask, “How can I make it even worse for my protagonist?”

The stakes should always seem life and death to the protagonist… they represent a complete change, the “death” of the former self. If your protagonist doesn’t have their self-identity shaken to its roots, you need to make this scene bigger.

5. Midpoint—the shift from victim to warriorAfter the first pinch point, the protagonist continues to face new challenges, but they are in a defensive role. They might be making some plans, but mostly they’re waiting for something to happen and reacting to events or circumstances beyond their control. If they try to solve any issue, they end up being thwarted or making things even worse. They might accidentally hurt someone, or their friends and family might start to lose trust in them. They begin questioning their identity and world view, which leads to a personality crisis, which leads to a shift in perspective.

This is about half way through the novel, and marks the point where the protagonist decides to take action. They decide to stop being a victim and reacting to events, and vow to do whatever it takes to win. They’ll probably form a new goal, and even if they aren’t sure how to achieve it yet, they’ll feel a deep conviction towards it. This might be based in rage or anger towards the antagonist, a newfound perspective, or increased self-confidence.

6. Second pinch point—the second battleThis leads to a second confrontation with the antagonist. It still may not be the main villain; it could just be henchmen that represent the main villain’s interests. It could be an attack, or it could be the result of the MC taking action, such as setting a trap for the antagonist.

The protagonist is determined to see this through, and feels personally responsible, even though the chances of success are slim. The conflict erupts into an open battle, with escalating consequences. This confrontation makes the protagonist realize that everything is much worse than they thought, and they realize they’ve underestimated the antagonist’s power. They rally with new determination, and might even score a seeming victory.

Alternatively, the second pinch point can be elevated conflict, followed by MC reaction. Maybe the antagonist has stolen something or kidnapped an ally. Your MC rallies the troops, and tries to fix things, but things keep getting worse and worse, leading to a total, devastating loss. Usually this process happens over several chapters.

7. Second plot point—the dark night of the soulThe plan failed. The secret weapon backfired. The hero’s team was slaughtered, or they lost their one advantage, or the antagonist’s evil plan succeeded. The worst has happened. The antagonist has won.

At the second plot point, everything the MC feared could happen, has happened. They are destroyed. They cannot win. They give up. There’s no hope. They lose the battle, with serious consequences. Someone the protagonist cares about got hurt, and they feel guilty. Usually the failure is due to their character flaw or a lack of knowledge.

This marks a period of depression, prompting a change in mindset—the MC has to give up what they want. They realize that the thing they’ve been holding on to is completely gone. There is no chance for victory. The only way forward is through. They are forced to change and go in a new direction.

This is tied to the MC’s flaw/lack of knowledge. When they figure out what they’ve been holding onto, what’s been holding them back or limiting them, and when they’re prepared to sacrifice what they want for the greater good, they finally become the hero they need to be to defeat the villain.

8. Final battle—the triumphUsually the MC needs a pep talk from a close friend, to “gird the loins.” They need a reason to fight, even if it’s hopeless. Even if they don’t see how to defeat the enemy. There’s no choice but to confront the antagonist.

But now they are prepared—they might have gained a valuable piece of knowledge or information. They might have been given a new weapon or power, or learned the villain’s weakness.

The final battle scene often includes a “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene, where the hero is caught, so the villain can gloat. Anyway it’s not a clear, easy victory. They fail at first, all is lost, the hero is captured, the enemy gloats… then the hero perseveres. With resolve and tenacity, the hero escapes and overpowers the villain.

Often the final battle scene also includes a “death of the hero” scene, where the hero, or an ally/romantic interest, sacrifices themselves, and appears to die… but then is brought back to life in joy and celebration. (Or if you want to keep it dark, just have them die, so the victory will be achieved but remain tragic).

This doesn’t have to be a literal “battle.” It’s just the last, final straw, the most dramatic part of your story. It’s what forces the MC to make a realization, change or grow. And it’s the place where the MC has a victory.

9. Return to ordinary worldThe hero returns home, changed. They’ve won, though it’s probably temporary (this villain was defeated, but he or someone new will return). The safety is short-lived and bittersweet.

The hero once again faces the small challenges or bullies at the beginning of the story, but they seem trivial now. The hero is no longer lacking; they’ve grown in confidence, and now have a group of new friends, and a new hope for the future.

Derek Murphy is a book designer with a PhD in Literature that now writes young adult fantasy novels and lives in castles. He publishes tips, tutorials and case-studies to help authors publish better-looking books and build author platforms that support a profitable writing career.

See Derek’s full Plot Dot plotting outline here. His plotting outline is inspired by three books: Plot Perfect, Story Grid, and Story Fix.

August 31, 2016

How to Start: Assemble the Pieces of Your Story

It can be hard to start a story. Just how do you transform an idea into words, then transform those words into a plot? Participant Sam Ritz goes into detail about the magic of assembling the pieces of your story:

Taking in a deep breath, my hands slide comfortably across the keyboard.

The cursor is blinking at me, keeping rhythm with the seconds ticking against the clock. My blank Microsoft Word document is waiting for me to fill it.

You’d think staring at a blank page that’s supposed to be a 50,000 word novel in 30 days would be intimidating. But you know what I see when I look at that blank page?

Freedom, and endless possibilities.

Outlines make me feel constricted, but having a blank page gives me the freedom to have my story go wherever my feelings take me.

So how do I start? Easy. I call them “puzzle pieces.”

Putting together the pieces…These puzzle pieces could be characters, the genre, a random scene, a type of conflict—anything really.

For example, for my first successful NaNoWriMo, I knew I wanted it to be YA (puzzle piece #1). I knew I wanted my main character to be a 13 or 14-year-old girl, still trying to find herself (puzzle piece #2), and I wanted her to have a slight love interest (puzzle piece #3). I wanted the story to take place during the zombie apocalypse (puzzle piece #4), and last but not least, I love historical fiction so I knew I wanted to incorporate some of that into the story, too (puzzle piece #5).

I also had a vague question in the back of my head: did I want to create a reason why the zombie apocalypse started in the first place, or did I want that to remain a mystery and just focus on the problems at hand in this new world? I told myself I would keep this little nugget to the side, focus on my characters and see if it would emerge later (It did! Or at least a piece of it did; this story eventually became a series).

Putting all these puzzle pieces together on the fly, getting to choose how they all work together—this kind of writing I think, is wonderful. I feel like when I write like this, I’m essentially having a “reader’s experience,” because I don’t know what the beginning, middle, and end entail (which I love). I feel the story working inside me, and because I don’t have a strict outline, I have the freedom to choose how it all plays out.

Do I come up with these ideas and each scene on the spot? Yes, but don’t cheapen that phrase. What it really means is that you’re listening to your intuition.

Sam Ritz is an aspiring author who would love to be traditionally published one day. She writes adult and young adult fiction, both with supernatural themes. Sam also like to incorporate a little bit of historical fiction into her work. She has been writing stories her entire life, but she credits NaNoWriMo with helping her finish my first novel—Sam now has six completed manuscripts! When she’s not writing or revising, Sam works in marketing at a community college and at a library.

Top photo by eebeejay.

August 29, 2016

How to Start: When Preparation Crosses the Line Into Procrastination

It can be hard to start a story. Just how do you transform an idea into words, then transform those words into a plot? _Erin Rand explains how to tell when you might be going overboard with your preparation:

Being a historical fiction writer, novel prep is often as big of a task as the actual writing process. Once I have the elements of a plot and characters, I become obsessed with figuring out how to best portray their lives within the time period I’ve chosen.

My most recent manuscript takes place in Boston during the Progressive Era, and my research ranged from combing through archives of The Boston Globe to walking around the old parts of the city, trying to get a feel for what my characters would have experienced. Figuring out what they would have worn and what sort of meals they would have eaten has sent me down some intense wormholes.

“My biggest writing vice is letting preparation become procrastination.”

At the same time, I have to remind myself not to get too bogged down by the minutiae. I could spend years combing through clothing catalogs and theater schedules from 1913, but there is a point where all those things stop becoming useful. The trick is to figure out when that point is.

While I’m acquiring a broad base of knowledge about the time period in which I’m writing (which usually involves a stack of handwritten notes that grows to about two inches thick), I always try to ask myself, “How does this information serve my characters? How does this inform their worldview?"

I’ve found that the more detailed my research becomes, the harder it is to answer that question. I might find it interesting to know the Majestic Theatre’s opera schedule for November 1913, but if my characters aren’t actually going to the opera, pursuing that line of research is time I could be using to get actual writing done. My biggest writing vice is letting preparation become procrastination.

Ultimately, the biggest hurdle between the preparation stage and the actual writing stage is accepting that there is no way I will know everything,

It’s possible to know everything about a time period, or even about my characters. I won’t know what I don’t know until I actually start writing. If I’m mid-novel and I realize that I really need to know how a Model-T was produced for my story to move forward, I can always take a break from writing to do the research. When I’m ready to get back down to business, my story will still be there.

Erin E Rand recently graduated from Emerson College with her MA in Publishing and Writing. She serves as the Editor in Chief of MinervaMag.com and the host of the Nostalgia Myalgia podcast. She lives in Phoenix, Arizona and you can find her musings on cacti and Harry Potter on Twitter at @erinerand.

Top photo by Flickr user f_lynx.

August 24, 2016

How to Start: A Five-Step Guide to Prepare for Your Novel

It can be hard to start a story. Just how do you transform an idea into words, then transform those words into a plot? Faith Blum, NaNoWriMo participant, shares

I’ve always been fascinated by how other people get started in their writing process for a new project.

My first novel was inspired by a picture and a story contest. For that novel, I had no outline and very little character development. I just wrote one word after another.

Since then, I have taken on various preparation methods for my writing projects.

For short stories, I do very little. For novellas, I do some character development and create a very loose outline. For novels, I write a flexible outline to get me started, but I don’t necessarily follow it. There are many times that the characters dictate a different course of action that works out much better than I could have ever planned.

“When the inspiration is there, I take it and I take it fast.”

When I outline a novel, I’m usually not very detailed to start. I have a rough idea of what I want the book to be about and what should happen, but beyond that, I just let my imagination and characters go. If I ever get stuck for more than a couple of days, though, I’ll outline the next few chapters with a lot of detail so I can get a move on.

When I’m excited to start a project, I don’t spend too much time planning it. If I need to tighten it up later, I can do that in the editing process. Or if my plot is too helter-skelter, I’ll take a break and do some outlining to put the book on the right track again. When the inspiration is there, I take it and I take it fast.

“Find a method that works for you.”For an example, here’s what I plan to do in the following month as I start my new novel:

Write up a rough outline on what I think my main character wants in his book.Do character sketches for the main characters.

Decide which pens and notebooks to use for the rough draft (yes, I write by hand).

Figure out a daily or weekly word-count goal.

Read through my outline and do any little bits of research I think are needed.

Once these are finished, then I’ll get started writing to my heart’s content. As I write, I sometimes do a little research, but if I don’t have time, I’ll just make a note to research it later.

If you’re just starting a writing project, you need to find a method that works for you. Or more than one if needed. As I’ve said, I use various methods myself and I now have twelve published books. If one thing doesn’t work, try another. The main thing to do is to keep writing.

Faith Blum started writing at an early age, and used to think she could write better than Dr. Seuss. Now that she has grown up a little more, she knows she will probably never reach the success of Dr. Seuss, but that doesn’t stop her from trying. When she isn’t writing, Faith enjoys doing many right-brained activities such as reading, crafting, playing piano, and playing games with her family. She currently lives on a hobby farm with her family in Wisconsin.

Top photo by Flickr user Gerry Snaps.

August 22, 2016

How to Start: Give Your Ideas Time to Breathe

It can be hard to start a story. Just how do you transform an idea into words, then transform those words into a plot? Ell Angelina, NaNoWriMo participant, shares the process she goes through to bring a story from conception to the page:

While I don’t like going for long periods of time without writing, I do prefer to let ideas age like a fine wine (or, since I don’t drink wine but am fond of smoothies, like an unripe banana).

If an idea stays with me for years, it must be worth exploring. No, it won’t be the same story that I envisioned when I first came up with the idea, but that’s okay. That’s good. I will see flaws I was blind to years earlier, or be able to combine two good ideas into a great one.

After I’ve decided to write something, I plot in many different ways. Sometimes I make a snap decision to make everything up as I go, other times I take a more methodical approach.

For NaNo in November, I tend to finish up my current writing projects in September. Then I start to plot out the story properly, finally allowing it out of the safe space in my brain. I create timelines, advanced character sheets, write an outline from start to finish (but with plenty of room for improvisation along the way), and research settings through most of October. Usually I’m done a week or so before November, so the last few days are spent looking over everything again, fine tuning the smallest details.

Once November 1st comes around, my story has been in the works for years, and the last few weeks have been nothing but a slow build-up to when I finally get to start writing it. When the clock finally strikes midnight I’m so excited I can barely even contain myself. I’m literally counting the minutes until I can finally put my story into words.

That’s how I love to start writing. To want it so badly you can think of nothing else.

Ell Angelina has participated in NaNoWriMo since 2 006 and isn’t quitting anytime soon. She works at a museum, often fulfilling the cliché of a bored receptionist that spends her work days writing a novel. Since 2014 she’s written several prize-winning short stories, been part of a short story collection and made several attempts at getting a full-length novel published (which she likes to think means that she’s tenacious, and not that her writing is bad).

Top photo by Flickr user Lex Photographic.

August 17, 2016

How to Find Your Own Writing Style

Tropes and cliches can be hard to avoid, especially when you’re working within specialized genres or categories. Tom Siddell, creator of the webcomic Gunnerkrigg Court , reminds us why it’s so important to write for yourself:

Sci-fi stories don’t always need spaceships, just like fantasy stories don’t always need swords and sorcery. In fact, relying on popular tropes might be off-putting to readers who already are not fans of a particular genre.

Keeping that in mind, I took elements of sci-fi and fantasy that I enjoyed and tried to present them in original and interesting ways when I started working on the story for my comic. I wanted to explore some of the fun, more obscure European myths, and I introduced those creatures irreverently. In contrast, the robots that inhabit the world of my comic have very spiritual personalities, and live strange, searching, solemn lives. I thought this was an interesting play on typical fantasy and sci-fi conventions.

Don’t go for style in your work, go for substance.Looking back at the early chapters of my comic, I realize I was trying too hard to be stylistic when I should have been aiming for clarity.

It’s tempting to see another creator’s “style” and want to emulate it or cultivate your own, but you don’t see the time and effort it took for that creator to reach that final, polished work you enjoy. This is especially true in-genre. You might think a fantasy story has to be told with a lofty, flowery language, or sci-fi is all about techno-babble and hard edges. Luckily, it doesn’t have to be that way! Be clear and to the point when trying to convey your message, and your own style will develop naturally.

You must be able to motivate yourself to work without outside influence. The urge to share your unfinished work and receive creative validation is tempting, but doing so can extinguish the creative spark that got you started in the first place.

You have to hold your own interest first, otherwise you will never hold the interest of others.Of course, once you finish your work, then you can start worrying about rewrites, editing and critique! When it comes to feedback, I listen to criticism about the nuts and bolts: the art, the pacing, the technical side of it.

When someone comments on the content of the story, I have to be objective. I try to make a distinction between genuine criticism and a reader’s personal preference in order to tell the story I want to tell.

Tom Siddell writes and draws the comic Gunnerkrigg Court, which can be found online, as well as in book and comic stores.

Top photo by Flickr user Samie Harding.

August 15, 2016

How to Avoid the Trap of Labeling Your Story

Tropes and cliches can be hard to avoid, especially when you’re working within specialized genres or categories. Meg Syverud and Jessica ‘Yoko’ Weaver, the creators behind webcomic Daughter of the Lilies, share why labels are unavoidable… and why that isn’t always a bad thing:

When someone asks you to describe your (or any) story to them, the most common answer sounds something like this:

“Halo meets Dragon Age.”

“It’s like if Harry Potter were a hard boiled detective.”

“Imagine if Supersize Me and Wolf of Wall Street were combined into one movie.”

But Mass Effect, The Dresden Files, and The Big Short—each referenced above—are all strong stories with their own individual identities. Why not just say what they are? Why do we need comp titles like this?

I’m going out on a limb to guess that you’ve used this to describe your own story—and granted, it’s the easiest way to give people the immediate gist. But at some point, you have to admit to yourself that your story isn’t exactly like anything that has been written before.

Humans like to organize and categorize things. Something is easier to understand when we give it a label, and stories are not excluded from this. Why is this the case, when stories, at their best, emulate the natural world, which is predisposed to chaos and disorder? Why are we so eager to drop stories into categories of Fantasy, Science Fiction, Coming of Age, or Slice of Life?

“How do you escape from the stigma of writing a paranormal romance?”

More importantly, how do you deal with the prejudice that comes from writing a story that is immediately categorized into one of these genres? How do you escape from the stigma of writing a paranormal romance, or from the assumption that your epic fantasy is based on Dungeons and Dragons?

Here’s the bad news:

You can’t.

But here’s the good news:

It doesn’t matter.

“Make sure what you’re writing has substance; that your message has weight.”

“I don’t believe” writes Brian McDonald in Invisible Ink (which you must read), “that [people] care much about the genre of a story; they just want to be moved in some way.”

In other words, the message trumps the messenger.

It’s why some titles—like The Iron Giant and Toy Story—can be so unexpectedly successful. It’s why some stories stay with you for your entire life: something in it sticks to your ribs, makes you question yourself, or brings new perspective. It doesn’t matter if it included magic, laser guns, lost treasures, or unstoppable viruses—the message it carried was the thing.

Make sure what you’re writing has substance; that your message has weight. Your readers will give your story 1,000 different labels because they will experience it in 1,000 different ways. Ultimately, though, those labels cannot accurately describe the soul of your story, much like how your own soul cannot be completely categorized by labels of gender or personality type.

Write something that needs to be said for the ones who need to hear it. It will make your story (whatever kind of story it is) last in the mind of your reader.

Meg Syverud has been an independent comic creator since 2004. She likes Pokemon, reading, video games, and cross stitching. She has a BFA in Graphic Design and a job as a Storyboard Revisionist. Her pet peeve is when people assume her current webcomic, Daughter of the Lilies, is based on D&D. Because it’s not.

Jessica “Yoko” Weaver has been working in independently published comics since 2010. She hopes and aims to one day work in video games and animations as a conceptual artist and designer. Despite her borderline obsessive love of red pandas, narseakittehs, and fatticorns she’s technically a highly functioning and responsible adult.

Top photo by Flickr user Katey Nicosia.

August 12, 2016

3 Tropes that Can Strip Nuance from Your Story

Tropes and cliches can be hard to avoid, especially when you’re working within specialized genres or categories. Author C. Chancy, also known as Vathara, shares three tropes she tries to avoid:

I currently write in two genres or categories: urban fantasy and fanfiction. I’ve found that many stories in both these categories can lean toward the following tropes… and end up losing something along the way:

‘Dark and Edgy’ to the max.The lone hero fights the good fight, but the villains keep getting stronger, the stakes higher, and the light at the end of the tunnel dimmer. We dip into the villain’s headspace more often than not; as if we’re only interested in the mindset of someone bound and determined to do Evil.

These stories lack Hope.

Everyone is treated as contemporary liberal Westerners, whether or not that makes sense.An Iron Age vampire slaughters his enemies and enslaves them, but rather than viewing his actions within the context of his time period and culture, he’s written off as evil without any nuance.

A religious person who says “No, I won’t serve same-sex marriage,” isn’t considered a product of her family and church; she’s an intolerable enemy who must be destroyed.

These stories lack Charity.

Characters change morals, ethics, and the habits of a lifetime at the drop of a hat.Sometimes they do this because the hero’s way is “obviously” better, or evil is so irresistibly tempting that only the protagonist could possibly stand against it.

These stories lack Faith.

I strive to write stories of hope, charity, and faith:

The Hope that, through characters’ actions, at the end of the day, the world can become just a bit better. The Charity to believe people can disagree without being mortal enemies, and that there’s more than one way to act honorably.The Faith that people—not just “heroes”—can have the inner strength to own an unshakable ethic.All told, urban fantasy and fanfic are both fun to play with, and I encourage anyone to break some tropes in the process. But there will be knocks along the way. Try to find some friendly beta-readers; it really helps!

C. Chancy has been in and out of dragon lairs since learning to read, usually with a map, compass, and something crunchy and good with chili sauce… just in case. Besides reading fantasy, SF, mysteries, and history, she also enjoys beading, manga, anime, digging up survival information, poking odd color combinations, and maintaining an aquarium of half-wild guppies and one huge South American catfish that likes to lurk unseen for weeks.

Photo by Flickr user TheGiantVermin.

August 10, 2016

3 Rules for Fantastic World-Building

Writers often dabble in the surreal, especially when writing fantasy or science fiction. We asked a few writers to share how they approach creating magical worlds. Today, K.M. Vanderbilt shares her three rules of thumb for creating a believable world:

When dealing with surrealism, writers often struggle with believability. It isn’t always easy for readers to embrace your vision.

Here are a few handy tricks:

Apply rules, world-build until your calluses are thick, and stay consistent within the bounds of your universe.

Take magic, for instance. Even if your mage can breathe fire and fart rainbows, an unchanging set of rules for these powers makes it more believable. I recommend Brandon Sanderson’s list of rules to get started. A system of checks and balances doesn’t just help suspension of disbelief; it also aids characterization. Your reader stays invested if fire-breathing comes with indigestion and rainbow farts result in a black-and-white world. Make your reader care when that character uses magic.

Avoid the trap of obvious plot devices.In my latest book, Errant Tides, deus ex machina reared its ugly head when a demigod’s power level removed needed tension and character development.

Likewise, in an out of character moment, a yellow-belly coward grew a spine without cause—and all because I insisted the plot had to develop that way.

Well, it didn’t, and my editor said as much. Neither circumstance did the book justice. Readers need to see characters struggle to overcome… or fail miserably. You know, whichever works best.

Staying within defined limits is difficult. Sometimes it’s easiest to start at the end and work backwards, especially when writing within a fantasy universe. Look at it like an algebra problem: solve for why (got dad jokes for days).

Why should readers care? What is the problem you’re presenting, and how have you made your solution believable? Identify unrealistic areas, then eradicate with extreme prejudice and adjust the writing accordingly. It can be time consuming, but it works.

Finally, consider how you’ve introduced fantastical elements.Sometimes, presenting a day full of magic as just another Monday is easiest. The less weird your world is for your character, the less weird it is for your reader.

My first book, Skeins Unfurled, uses “It was a Monday” from the outset. I combined different pantheons to populate the Norse system of nine worlds. That mix creates surrealism. Sekhmet and Zeus aren’t supposed to be drinking buddies, but—you got it—it was a Monday.

So there you have it. My experience with surrealism is a mixed bag. I’ve used all of these approaches at least once, some in concert. How helpful they are depends on genre, your world, and your writing style. In the end: be consistent with what you create. If you build it, they will read and believe it.

Write on, you dirty wordsmiths. There’s a story waiting to be told; nobody can write it like you.

K. M. Vanderbilt is a dirty smoker and a lover of all things gore. She lives with her hetero life-mate, single offspring, and a derpy canine in the urban sprawl of Colorado Springs, but dreams about relocating to Neptune in the next fifty years. In the meantime, she writes. Her debut dark fantasy novel, Skeins Unfurled, is available on Amazon.

Top photo by Flickr user avrene.

August 8, 2016

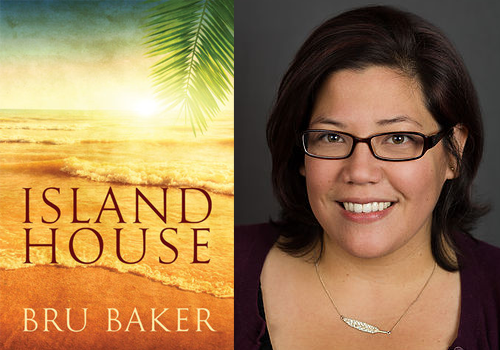

I Published My NaNo-Novel: Staying True to Your Story

Bru Baker started participating in NaNoWriMo in 2010, and went on to publish the novel she wrote that year, Island House. She tells us about the experience, including having her eyes opened to the genre hierarchy, and why it matters to tell the story you’re passionate about:

When I signed a contract to publish my 2010 NaNoWriMo novel, Island House, I didn’t realize romance was a bit of a dirty word in the book industry. Or that since my characters were both men, my book would be further marginalized by being categorized into a sub-genre: gay romance. I had written this novel for the joy of writing it, and, at the time, was just thrilled to find there was a market for what I had produced.

I was proud to join the ranks of published authors and not at all prepared for the subtle (and not so subtle) snubs that a genre author receives. I had no idea certain genres of fiction were looked down on by some people because they weren’t part of mainstream fiction.

I didn’t understand that retailers bury genre fiction on their virtual shelves. That probably goes for their physical shelves, too, but as a writer in a sub-genre, I’ve never had the opportunity to see my books on a bookstore shelf.

I also wasn’t prepared for the way some mainstream authors belittle genre works. I’d never thought of “trope” as an insult until it was said to me with a sneer by an author who thought genre fiction was a waste of time. I was surprised I needed to justify my seat at the fiction table, but I’ll defend my right to be there—and yours, too!—until such casual dismissal isn’t commonplace.

That being said, I’d never warn a writer away from genre fiction.

“Your words shine when you’re being true to yourself and your style.”If westerns are your thing, write westerns. If the story that dogs you day and night is a romantic suspense paranormal mystery, then write it! Your words shine when you’re being true to yourself and your style. At the end of the day, I’d rather have a book I’m proud of than something I hacked together because I was following mainstream trends.

Publishing is an ever-changing landscape, and I’ve seen a lot of positive changes over the six years I’ve been a part of it. The advent of niche publishers has made it easier for genre writers to get their books published, and social media is perhaps the greatest tool in a genre author’s belt. Putting yourself out there will help readers who love those genres find your books. Having a presence on sites where readers look to discover new authors like Goodreads, NetGalley and BookBub is helpful, too.

A good story is a good story, and at the end of the day, that’s what matters to readers. And if yours is a tragi-comedy space opera as told in the POV of the ship’s cat, you’d better believe there’s a reader out there who’s been looking for a book just like that for years. It may take some time and patience to find your niche, but never let anyone tell you you’re less of a writer because you aren’t in the mainstream.

Bru Baker is a former journalist who made the jump to writing fiction in 2010, when she entered her first NaNoWriMo. She balances her time between writing gay romance with Dreamspinner Press and working in reference and reader’s advisory for a Midwestern library. She’s happiest when she’s either writing a book or surrounded by them. Her next release, More than Okay, will be out in late September.

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers