Malcolm R. Campbell's Blog, page 56

April 1, 2022

‘Winterkill’ from the award-winning Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch coming in September

The Holodomor, also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a famine in Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The term “Holodomor” emphasizes the famine’s man-made nature and alleged intentional aspects such as rejection of outside aid, confiscation of all household foodstuffs, and restriction of population movement. The Holodomor famine was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1932–1933 which affected the major grain-producing areas of the country. Ukraine was home to one of the largest grain-producing states in the USSR and as a result, was hit particularly hard by the famine. Millions of inhabitants of Ukraine, the majority of whom were ethnic Ukrainians, died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in Ukrainian history. Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by Ukraine alongside 15 other countries as a genocide against the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet government. – Wikipedia

I met Marsha online some 30 years ago when CompuServe and its forums were kings of the Internet. It was obvious to me then that she had both the passion and the talent to bring obscure historical events (as we view history in the States) to light in award-winning novels. As Ukraine fights, once again the evil thrust upon it from Russia this is the perfect time to remind people that such atrocities have happened before. I hope a large number of people will pre-order this novel.

From the Publisher:

Ukrainian Canadian author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch tells a gripping story of how the Soviet Union starved the Ukrainian people in the 1930s — and of their determination to overcome.

Ukrainian Canadian author Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch tells a gripping story of how the Soviet Union starved the Ukrainian people in the 1930s — and of their determination to overcome.

Nyl is just trying to stay alive. Ever since the Soviet dictator, Stalin, started to take control of farms like the one Nyl’s family lives on, there is less and less food to go around. On top of bad harvests and a harsh winter, conditions worsen until it’s clear the lack of food is not just chance… but a murderous plan leading all the way to Stalin.

Alice has recently arrived from Canada with her father, who is here to work for the Soviets… until they realize that the people suffering the most are all ethnically Ukrainian, like Nyl. Something is very wrong, and Alice is determined to help.

Desperate, Nyl and Alice come up with an audacious plan that could save both of them — and their community. But can they survive long enough to succeed?

Known as the Holodomor, or death by starvation, Ukraine’s Famine-Genocide in the 1930s was deliberately caused by the Soviets to erase the Ukrainian people and culture. Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch brings this lesser-known, but deeply resonant, historical world to life in a story about unity, perseverance, and the irrepressible hunger to survive.

–

March 31, 2022

Jim Wrinn led Trains Magazine with passion

WAUKESHA, Wis. — Jim Wrinn, who aspired since his youth to be the editor of Trains magazine and served in the role for more than 17 years, died at home on March 30, 2022, after a valiant 14-month battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 61.

Wrinn’s longevity in the editor’s role was second only to that of the legendary David P. Morgan, who led the magazine for more than 33 years and died in 1990 at age 62. Morgan’s editorship and writings deeply influenced Wrinn, who began reading Trains in 1967 at age 6.

History left it to Wrinn to preside over a challenging, transitional era for Trains, which Kalmbach Media predecessor Kalmbach Publishing Co. launched in November 1940. As editor in chief, Wrinn was fortunate to serve generations of readers who grew up on the print magazine while at the same time broadening the magazine’s appeal to a new digitally oriented audience.

Source: Jim Wrinn led Trains Magazine with passion – Trains Wrinn at the Trains “81 for 81” event at the Nevada Northern Railway Museum in October 2021. Under his editorship, the magazine broadened its scope to include events like photo charters. (Cate Kratville-Wrinn)

Wrinn at the Trains “81 for 81” event at the Nevada Northern Railway Museum in October 2021. Under his editorship, the magazine broadened its scope to include events like photo charters. (Cate Kratville-Wrinn)

–

I met Jim Wrinn in the early 1990s when he was a reporter for a North Carolina newspaper and a volunteer at the North Carolina Transportation Museum. At the time, my wife and I were volunteers at the Southeastern Railway Museum in Atlanta. We visited each other’s museums, learned a lot from his experience, drank his beer, and stayed in his house whenever we were in Salisbury, NC. His books and articles were an education in themselves. I will miss him, and the railroading world from professionals to railfans will miss his voice and his leadership.

–Malcolm

March 30, 2022

‘The House of the Spirits’

“When I start I am in a total limbo. I don’t have any idea where the story is going or what is going to happen or why I am writing it. I only know that—in a way that I can’t even understand at the time—I am connected to the story. I have chosen that story because it was important to me in the past or it will be in the future.” – Isabel Allende

I am re-reading The House of the Spirits for the first time since it came out in English in 1985, most likely from the copy I read then. Allende is one of my favorite writers (perhaps above all others) because the stories she tells resonate with me as does the fact she begins each of her books–and I’ve read most of them–without knowing where the story is going. The House of the Spirits didn’t disappoint me in the mid-1980s, and yet, I was afraid to go back to it for fear the most perfect novel would have become imperfect over time like a first lover you don’t dare meet again after both of you have grown up.

I am re-reading The House of the Spirits for the first time since it came out in English in 1985, most likely from the copy I read then. Allende is one of my favorite writers (perhaps above all others) because the stories she tells resonate with me as does the fact she begins each of her books–and I’ve read most of them–without knowing where the story is going. The House of the Spirits didn’t disappoint me in the mid-1980s, and yet, I was afraid to go back to it for fear the most perfect novel would have become imperfect over time like a first lover you don’t dare meet again after both of you have grown up.

I can’t imagine knowing where a story is going when I start writing it and fear that if I did, I wouldn’t be able to write it, or that if I wrote it anyway it would be less true. As I re-read this magical realism novel, I’m not disappointed the second time out and I feel inspired now as I did over thirty years ago; I see again that the story unfolded as it had to unfold because it was (and is) all of a piece that existed in and of itself before Allende wrote the first line: “Barrabus came to us by sea.”

“I think that the stories choose me,” she has said.

When I chanced across author Mark David Gerson’s book The Voice of the Muse in 2008, I was surprised to find a book for writers that acknowledged the truth that stories exist untold until we find them and/or until they find us. As I wrote in my Amazon review of his book, “Gerson believes stories pre-exist, waiting hidden away in dreams to come alive. But while I’ve worked more or less as a blacksmith hammering them into this world, he provides ways to tune into the ‘muse stream’ whereupon life flows onto the page like a warm sweet river.”

I suspect Allende knows this to be true. Otherwise, she couldn’t have written this:

He could hardly guess that the solemn, cubic, dense, pompous house, which sat like a hat amidst its green and geometric surroundings, would end up full of protuberances and incrustations, of twisted staircases that led to empty spaces, of turrets, or small windows and could not be opened, doors hanging in midair, crooked hallways, and portholes that linked the living quarters so that people could communicate during the siesta, all of which were Clara’s inspiration.

I’m relieved to discover that I’m still in love with this novel and that life might have been better if I hadn’t stayed away from it for so many years.

My stories come upon me out of nowhere and that’s for the best.

My stories come upon me out of nowhere and that’s for the best.

March 29, 2022

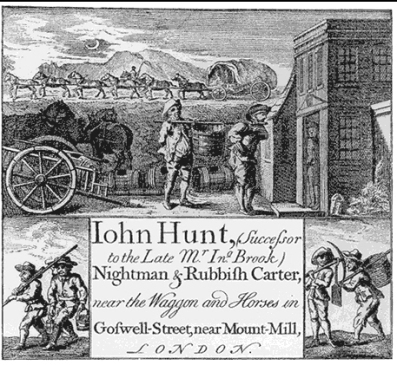

Septic Tank Service Day

The Soylent Green Company truck stopped by the house today and pumped out the septic tank. The first house on this lot had a privy. A year before we built our house on the land where my wife’s grandparents had their house (long gone), the county changed its rules about septic tanks. Previously, a simple perc test was all it took to get approved for a septic tank. But then progress came along and septic tank systems had to meet stricter requirements and that cost a lot more money.

The Soylent Green Company truck stopped by the house today and pumped out the septic tank. The first house on this lot had a privy. A year before we built our house on the land where my wife’s grandparents had their house (long gone), the county changed its rules about septic tanks. Previously, a simple perc test was all it took to get approved for a septic tank. But then progress came along and septic tank systems had to meet stricter requirements and that cost a lot more money.

My comment when we found this out late in the home building game was, “So there are 80 cattle doing their business on the other side of the fence without any restrictions, and you guys are worried about the two humans inside the house?”

Apparently so. There’s not a lot of money in the nigh soil business these days. We’re more toxic than the birds and the bees and the critters out there in the woods.

So no, I did not take a selfie of myself posing in front of the honey wagon and post it on Facebook or, worse yet, keep it to share with all of you in this post. In fact, I don’t know why I’m writing this post.

That is to say, modern-day job hunters aren’t flocking to the septic tank business in droves. And, a career as a night soil coolie never caught on in this country. Actually, I thought about all this yesterday when I was writing about climbing 8,000-meter peaks where the problem, on Mt. Everest, for example, is dealing with human waste. It’s out of control, actually.

Short term, we could FedEx that waste to Putin. Long-term, what the hell do we do with it? It goes to waste treatment plants, though I often wonder how much ends up in the river. Or the food trucks on main street. Or gravy.

March 28, 2022

High-altitude dreams

K2 – second-highest mountain

K2 – second-highest mountain

When I was in middle school, I decided I wanted to climb mountains. I was influenced by the fact my father climbed mountains in Colorado while he was in college (something I would do later when I was in college). I was also influenced by the books in our house about early mountaineers’ attempts in the Himalayas (including Mt. Everest) and the Karakoram (including K2) mountain ranges. I never knew for sure whether my father had these books because climbing quests made exciting reading or because he often hoped to climb those peaks himself.

Then, in 1953, when newspapers told the story of the first successful climb of Mt. Everest by Edmund Hillary (New Zealand) and Tenzing Norgay (Nepal), I was sold on the idea that such climbs were possible. K2, which is more difficult, was successfully climbed by an Italian expedition a year later. The family applauded my 14,000-foot peak climbs in Colorado but thought my notions of climbing Everest and K2 were insane. “So what?” I asked.

One of the larger family arguments occurred when I wanted to sign up with a trekking tour group to hike to the Mt. Everest base camp. I admit it was a bit costly (it’s more expensive now!) In part, nobody believed that once I visited the base camp for several weeks I wouldn’t ultimately push for an actual climb later. I probably would have.

For non-climbers, the statistics don’t look good: 14.1% of those who attempt Mt. Everest die on the mountain; 22.9% of those who attempt K2 never come back. But I look on the bright side: more people came back than don’t. Plus, I always said, one isn’t going to die on the mountain unless his/her number is up. If your number’s up, you’ll die some other way–like falling off a stepladder while changing a lightbulb. The family and I didn’t come to a meeting of the minds about the dangers.

Among other things, they weren’t excited about the fact that most of those who die on 8000-meter peaks are still there, impossible to recover. That didn’t excite me either, but it never changed my high-altitude dreams. My family can rest easy now. People my age are no longer allowed to climb Mt. Everest. So now I grieve what might have been and allow the characters in my novels to see the top of the world, a vision that changes everyone who makes a round trip.

I include high-altitude dreams in my novels “Mountain Song” and “At Sea.”

I include high-altitude dreams in my novels “Mountain Song” and “At Sea.”

March 26, 2022

Sunday potpourri on Saturday

My contemporary fantasy The Sun Singer will be free on Kindle from March 27 through March 31. This is a hero’s journey novel set in Glacier National Park.I’m happy to say that after having hormone shots every six months to supplement the radiation treatments I had for prostate cancer several years ago, I’m now done with the shots. The last one was Wednesday. They’re worse than tetanus shots when you get them and provide you with a few days of weird after-effects.

My contemporary fantasy The Sun Singer will be free on Kindle from March 27 through March 31. This is a hero’s journey novel set in Glacier National Park.I’m happy to say that after having hormone shots every six months to supplement the radiation treatments I had for prostate cancer several years ago, I’m now done with the shots. The last one was Wednesday. They’re worse than tetanus shots when you get them and provide you with a few days of weird after-effects.

When I wrote yesterday’s post about sex scenes, I didn’t have space to mention that some authors have plenty of sex in their novels without writing the scenes. They include a lot of innuendoes but never include the actual encounters. One author I’m thinking of here is Stuart Woods whose output includes his series of Stone Barrington novels. Stone jumps into bed with almost every woman he meets, but we never see it happen. The books are basically crime thrillers.

When I wrote yesterday’s post about sex scenes, I didn’t have space to mention that some authors have plenty of sex in their novels without writing the scenes. They include a lot of innuendoes but never include the actual encounters. One author I’m thinking of here is Stuart Woods whose output includes his series of Stone Barrington novels. Stone jumps into bed with almost every woman he meets, but we never see it happen. The books are basically crime thrillers. While our drip coffee makers last about 12-18 months, our microwave has lasted at least ten years. Now it’s shutting itself off whenever we cook something on high for 10-15 minutes. So, we ordered a new Hamilton Beach and have it ready to go as soon as our trusty Sharp bites the dust. The appliances my parents bought during, or just after, WWII lasted longer than my parents. I wish today’s products were just as durable.

While our drip coffee makers last about 12-18 months, our microwave has lasted at least ten years. Now it’s shutting itself off whenever we cook something on high for 10-15 minutes. So, we ordered a new Hamilton Beach and have it ready to go as soon as our trusty Sharp bites the dust. The appliances my parents bought during, or just after, WWII lasted longer than my parents. I wish today’s products were just as durable.

While working on a short story set in Tallahassee, Florida’s former Smokey Hollow neighborhood, I was surprised to hear from people who said they were born and raised in Tallahassee and had never heard of it. Then it occurred to me that the neighborhood was destroyed by “urban renewal” in the 1960s, possibly before the people commenting online were born. If you live in Tallahassee and want to learn more, I found More Than Just a Place to be a handy reference.

While working on a short story set in Tallahassee, Florida’s former Smokey Hollow neighborhood, I was surprised to hear from people who said they were born and raised in Tallahassee and had never heard of it. Then it occurred to me that the neighborhood was destroyed by “urban renewal” in the 1960s, possibly before the people commenting online were born. If you live in Tallahassee and want to learn more, I found More Than Just a Place to be a handy reference.

I like the idea of authors getting together to support Ukraine, offering their signed work for an online auction that will run from March 19 through April 12. Unfortunately, I heard about it too late to get involved But what a great idea. I hope the auction raises a lot of money to combat the madness coming out of Russia.

I like the idea of authors getting together to support Ukraine, offering their signed work for an online auction that will run from March 19 through April 12. Unfortunately, I heard about it too late to get involved But what a great idea. I hope the auction raises a lot of money to combat the madness coming out of Russia.

March 25, 2022

Keeping your book out of the Bad Sex in Fiction Awards

“My whole practical thesis around the craft of writing a sex scene is this: it is exactly the same as any other scene. Our isolation of sex from other kinds of scenes is not indicative of sex’s difference, but the difference in our relationship to sex. It is our reluctance to name things, the shame we’ve been taught, our fraught compulsion to enact a theater of types. It is indicative of the lack of imagination that centuries of patriarchy and white supremacy has wrought on us.” – Melissa Febos in Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

Among other things, Febos thinks sex scenes should advance the plot. Writers tend to forget that everything in their novels and stories is supposed to advance the plot directly or indirectly. If they haven’t forgotten this, they forget it when they try to write a sex scene.

Among other things, Febos thinks sex scenes should advance the plot. Writers tend to forget that everything in their novels and stories is supposed to advance the plot directly or indirectly. If they haven’t forgotten this, they forget it when they try to write a sex scene.

According to NY Book Editors, “When you write sex scenes, it’s gonna get raw. There are arms, legs, emotions, sweat, and nipples. If that made you squirm, you’re not ready.”

Apparently, a lot of aspiring writers aren’t ready.

Febos suggests that writers can unlearn all of their incorrect ideas about sex scenes just as they can unlearn other bad habits (such as writing in passive voice). I like this way of looking at it. The problem is, most of the typical bad habits aspiring writers are fraught with are covered in writing books and (usually) bad sex scenes isn’t in the table of contents.

As a reader, I’ve found that some of the best sex scenes in novels not only advance the plot, but leave you thinking, “Gosh, I didn’t know you could do that.” So, perhaps we should add that good sex scenes should be educational. But don’t take notes: if you do, the next time you’re making love, you don’t want your partner to say, “OMG, we’re doing page 43 in Malcolm R. Campbell’s novel The Gigolo Blues.”

Let’s forget I said that and suggest we’ve gone past the days when all sex scenes are allowed to sound the same (a common joke about sex scenes in romance novels years ago) and write something that could only appear in the story and with the characters a writer’s working on right now. If the scene sounds like something you read on page 43 of any novel, the author has a problem.

The problem might be a long list of inhibitions that are more advanced than, “What if mom reads this.” NY Book Editors says, “Come back after you’ve eaten some nachos, downed a beer, and thrown modesty out of the way.” They do make some good points, though I think they’ll be hard to put into practice without therapy, a lof practice (with sex or writing), or considering some of the deeper reasons why these scenes are a continuing problem.

Febos’ book might be a good place to start. But first, here’s an excerpt with some ideas worth pondering. If the excerpt makes you squirm, you probably need the book–or a good hypnotist.

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of the four-book Florida Folk Magic Series. If you want the entire series, you can find it bound together in one Kindle volume at a savings.

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of the four-book Florida Folk Magic Series. If you want the entire series, you can find it bound together in one Kindle volume at a savings.

March 23, 2022

Online Auction: Bid on signed books to help Ukraine

March 21, 2022

Let’s learn Gàidhlig this week

Since the gods have blessed me with a Scots ancestry, I know without looking it up that “Gàidhlig” is Scots Gaelic. While I read and generally understand spoken Scots (a completely separate and distinct language from English or Gàidhlig), I’m in bad shape then it comes to Gàidhlig, so I must warn you that achievieving luency won’t be a peace of cake even if you have all of Gaelic singer Julie Fowlis’ recordings.

Since the gods have blessed me with a Scots ancestry, I know without looking it up that “Gàidhlig” is Scots Gaelic. While I read and generally understand spoken Scots (a completely separate and distinct language from English or Gàidhlig), I’m in bad shape then it comes to Gàidhlig, so I must warn you that achievieving luency won’t be a peace of cake even if you have all of Gaelic singer Julie Fowlis’ recordings.

As you can tell by the graphic, I didn’t throw a dart at the calendar to pick when all of you will start learning Gàidhlig.

Benefits of learning Gàidhlig You can listen to Julie Fowlis’ songs without having to read the “liner-notes” translation.When you visit Scotland, especially the Outer Hebrides, and hear people shouting, you’ll be able to tell whether or not they’re swearing at you. If you hear, “Gorach Pios De Cac,” you should leave.You and your significant other can whisper sweet nothings to each other here in the States without other people listening in. For example, you can say “Feumaidh sinn rùm fhaighinn” and those next to you in the Walmart checkout line won’t have a clue–not that they do anyhow–unless you’re acting like you need to get a room.You’ll be supporting the efforts of those who are trying to keep Gàidhlig from becoming extinct. Only 1.1% of Scots speak it while 30% speak Scots.You’ll be doing your part to make the world a better place. As the World Gaelic Week site suggests, Remember that you download the official Seachdain na Gàidhlig Resources here or access Gaelic language resources here.You’ll know how true Highlanders really speak as opposed to the Scots that many novelists have them speaking. (For shame.)And, you’ll know my feelings about you, dear reader:

You can listen to Julie Fowlis’ songs without having to read the “liner-notes” translation.When you visit Scotland, especially the Outer Hebrides, and hear people shouting, you’ll be able to tell whether or not they’re swearing at you. If you hear, “Gorach Pios De Cac,” you should leave.You and your significant other can whisper sweet nothings to each other here in the States without other people listening in. For example, you can say “Feumaidh sinn rùm fhaighinn” and those next to you in the Walmart checkout line won’t have a clue–not that they do anyhow–unless you’re acting like you need to get a room.You’ll be supporting the efforts of those who are trying to keep Gàidhlig from becoming extinct. Only 1.1% of Scots speak it while 30% speak Scots.You’ll be doing your part to make the world a better place. As the World Gaelic Week site suggests, Remember that you download the official Seachdain na Gàidhlig Resources here or access Gaelic language resources here.You’ll know how true Highlanders really speak as opposed to the Scots that many novelists have them speaking. (For shame.)And, you’ll know my feelings about you, dear reader:Tha thu am measg cuid de na leughadairean as fheàrr air aghaidh na Talmhainn agus bu chòir dhut duais fhaighinn airson mo bhlog a leughadh.

March 19, 2022

Scene Setting in Novels – Part II

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned that “scene setting” remains a popular technique for beginning a story or a novel. According to Janice Hardy, “The opening scene is the first glimpse readers get of the novel. It’s an audition for their time, and provides the critical elements and details they’ll need to understand the story, protagonist, and setting. Some novels open with the story, but others open with a prologue or glimpse of something outside the main characters and time frame.”

The overarching metaphore in my short story “Moonlight and Ghosts” is moonlight, so moonlight was my focus in the story’s opening: “The light of the harvest moon was brilliant all over the Florida Panhandle. It released the shadows from Tallahassee’s hills, found the sandy roads and sawtooth palmetto sheltering blackwater rivers flowing through pine forests and swamps toward the gulf and, farther westward along the barrier islands, that far-reaching light favored the foam on the waves following the incoming tide. Neither lack of diligence nor resolve caused that September 1985 moon to remain blind to the grounds of the old hospital between the rust-stained walls and the barbed wire fence, for the trash trees and wild azalea were unrestrained, swings and slides stood dour and suffocated in the thicket-choked playground, humus and the detritus of long-neglect filled the cracked therapy wading pool, and fallen gutters, and shingles and broken window panes covered the deeply buried dead that had been left behind.” [Copyright © 2019 Malcolm R. Campbell]

One way to add depth to a scene setting opening is through a reference to a scene in a novel, short story, or film. In my case, my opening lines were inspired by the closing lines of the James Joyce novella-length short story “The Dead” which appeared in his 1914 Dubliners collection that focussed on middle class life. I didn’t mention the link in my story, because mentioning it didn’t really fit, and because what I was thinking about was Joyce’s use of a snow metaphore in a story about the dead (which is how my character saw the existence of forgotten people in mental instutions). Here’s Joyce’s closing to “The Dead”:

One way to add depth to a scene setting opening is through a reference to a scene in a novel, short story, or film. In my case, my opening lines were inspired by the closing lines of the James Joyce novella-length short story “The Dead” which appeared in his 1914 Dubliners collection that focussed on middle class life. I didn’t mention the link in my story, because mentioning it didn’t really fit, and because what I was thinking about was Joyce’s use of a snow metaphore in a story about the dead (which is how my character saw the existence of forgotten people in mental instutions). Here’s Joyce’s closing to “The Dead”:

“Snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

Those who recognized the structure of my opening, would understand–as they read the story–my allusion to Joyce’s story and snow metaphor. Those who didn’t recognize it really didn’t lose anything except another piece of information.

My indirect reference to “The Dead” was in no way an attempt to elevate my story to the level attained by Joyce’s story that T. S. Eliot said was “one of the greatest short stories ever written.” You can read Joyce’s story here. John Huston adapted the short story for the screen in his 1987 film starring his daughter Anjelica Huston. The closing lines of Joyce’s story made a very effective voice-over in the film.

I agree with Shmoop’s contention that those lines are among the most famous in 20th century literature. Sparknotes states that “The snowfall itself, like death, is indifferent; it falls on everyone dead and alive, regardless of class and nationality. In this way, death is also the great unifier between past and present, suggesting a broader connection to ‘the wisdom of the ages.'”

I view light, moonlight or other light, the same way: it’s a force that is open to everyone, ghosts or otherwise, though I don’t think the light is indifferent. These thoughts inspired by “The Dead” were on my mind as I wrote “Moonlight and Ghosts,” the opening story in Widely Scattered Ghosts.