Malcolm R. Campbell's Blog, page 190

July 26, 2016

Wow, almost 100,000 views for this blog

Aw shucks, folks, thanks for all the visits and for putting up with the fact I haven’t felt the need to place this blog squarely in one niche or another.

The all-time favorite post is: The Bare-bones structure of a fairy tale. Even though that post is a little over two years old, it still out performs every new post from week to week. I have no idea why, but at over 7,000 views, it’s well ahead of the rest of my 1,065 of posts since 2007.

The second most popular post is: Heave Out and Trice Up. This, I understand. A lot of people search for the meanings of navy jargon and slang, most especially what “heave out and trice up” actually means. This post was written in 2010 and still gets hits every week.

I’ve done a lot of reviews on this site, a few author interviews from time to time and talked about writing (including my own). Those posts are in the majority. However, when north Florida’s notorious Dozier School was in the news, my 2012 post about the White House Boys got a lot of hits. So did my 2013 (and frequently updated) post about the fate of the aircraft carrier USS Ranger that was scrapped rather than turned into a museum.

Since my books are mostly set in Montana’s Glacier National Park and the Florida Panhandle, I’ve written posts about my stories’ settings. Those get more hits over time than they do on the day they appear. I’m glad you find them whenever you find them.

I’ve appreciated your comments over the years as well. One never knows what people will say. I do know it takes time for you to write them.

Want a chance at a free Kindle Fire?

For those of you who’ve enjoyed reading my books and short stories, I want to mention that my publisher is starting a newsletter. I hope you’ll sign up. It’s free. Better yet, one subscriber will receive a free Kindle Fire Tablet. Deadline is 16 days from now. Click here to subscribe and enter the random drawing for the Kindle.

As for heaving and tricing

Now, for those of you who are curious about heave out and trice up, it has nothing to do with throwing up while seasick or drunk. I don’t know if navy ships still use the phrase as a wake-up call over the ship’s public address system. It means get up and raise your bunk (rack) or hammock up away from the floor (deck) so that the compartment cleaners can sweep out your berthing (sleeping, not having babies) area.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell writes magical realism, contemporary fantasy and paranormal novels and short stories.

July 23, 2016

How does your worldview influence your writing?

When you read a hard-as-nails police or espionage novel, do you wonder about the worldview of the author? Do you assume s/he’s politically conservative, possibly career law enforcement or military, and/or heavily interested in weapons, military strategy, law and order issues and personal and national security?

When you read a novel about people coming of age, discovering themselves in hero’s journey styled stories, or finding love among the ruins, do you wonder if the author is writing out of his or her own philosophy of life and “the big picture”? Do you assume s/he is politically liberal, possibly a teacher or a psychologist, and/or heavily interested in social programs, personal and religious freedom and a lifetime of learning?

I’m not sure we should make these assumptions. If we do, we might be surprised how often an author writes “against typecasting.”

On the other hand, many of us write short stories and novels that are heavily influenced by our “philosophy of life” or our view of the universe and an individual’s place within it. When I read a page-turning espionage novel and marvel at the author’s knowledge of weapons and tactics, I see quite clearly that I could never write such a book. I have no experience with military weapons and have never been drawn to study them, much less to form a clear picture about their technical differences or what it would be like to use them in a real world situation.

On the other hand, many of us write short stories and novels that are heavily influenced by our “philosophy of life” or our view of the universe and an individual’s place within it. When I read a page-turning espionage novel and marvel at the author’s knowledge of weapons and tactics, I see quite clearly that I could never write such a book. I have no experience with military weapons and have never been drawn to study them, much less to form a clear picture about their technical differences or what it would be like to use them in a real world situation.

On the other hand, when I read a magical realism novel I assume that the author has an affinity for the magic and the stories generally associated with the time and place in which the story is set. A good researcher can find out what myths and legends might apply to a town or a region. But blending those into a story probably requires a sense of magic just as a spy novel often requires its author to have a sense of weapons and combat situations.

Perhaps somebody has written a doctoral dissertation or a definitive book about stories and the authors who tell them. Perhaps there’s research out there that shows the connections (or lack of connections) between authors’ books and authors’ political/philosophical/religious beliefs.

Personally, I see writing within–or somewhat within–one’s worldview as another way of writing what you know. Expediently, it’s a practical approach because in general terms, our worldview is our comfort zone. We know more about how situations within that view might unfold and how characters embracing our attacking that worldview might develop, react and think. Some (perhaps many) authors might refute this idea by showing how they have been a chameleon–so to speak–by writing books that contrast so greatly with each other that readers could only conclude that they have no worldview at all, have multiple worldviews, or changed their worldviews over time.

That said, perhaps my musings on this subject boil down to this opinion: If you’re an emerging writer, writing from within your worldview gives you a greater chance of “getting it right” than writing about characters and events you don’t grok in your daily life.

That’s my experience. What’s your experience?

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of fantasy (“The Sun Singer,” “Sarabande”), paranormal (“Moonlight and Ghosts,” “Cora’s Crossing), and magical realism (“Conjure Woman’s Cat,” “Emily’s Stories,” “Willing Spirits”) novels and stories.

July 20, 2016

Briefly Noted: ‘Beyond Schoolmarms and Madams: Montana Women’s Stories’

Beyond Schoolmarms and Madams: Montana Women’s Stories, edited by Martha Kohl (Montana Historical Society Press: May 2016), 288 pages, over 100 photographs.

When the histories of the west we studied in high school were written, the emphasis was on great men, both saints and devils, and what they did. We’re slowly finding out there was more to the story; this new book edited by Martha Kohl is part of our re-education. (I’m not sure why the cover photograph shown on Amazon has a slightly different subtitle than the book’s listing or the cover as shown on the MHS site.)

When the histories of the west we studied in high school were written, the emphasis was on great men, both saints and devils, and what they did. We’re slowly finding out there was more to the story; this new book edited by Martha Kohl is part of our re-education. (I’m not sure why the cover photograph shown on Amazon has a slightly different subtitle than the book’s listing or the cover as shown on the MHS site.)

From the Publisher:

“Sheriff Garfield had just been elected to a second term in 1920 when he was fatally shot. His wife Ruth, a ranching woman with a young son, set aside her grief to serve out her husband’s term. She was Montana’s first female sheriff and served two years.

“Stories like Ruth Garfield’s fill the pages of Beyond Schoolmarms and Madams: Montana Women’s Stories. The women featured in this book range from late eighteenth-century Indian women warriors to twenty-first century Blackfeet banker Elouise Cobell. They span geography―from the western Montana women who worked for the Forest Service, to Miles City doctor Sadie Lindeberg. And they span ideology―from the members of the Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, who led the fight for laws banning segregation in public accommodations, to the Women of the Ku Klux Klan. With grit and foresight, these women shaped Montana.”

From the Great Falls Tribune:

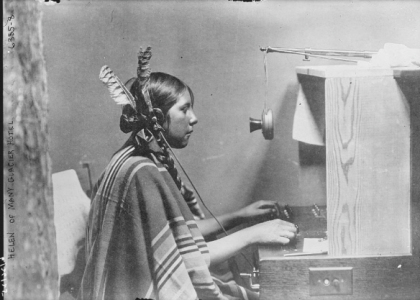

Telephone operators worked at hotels as well as at exchanges. Photographed here is Helen (last name unknown), an operator at Many Glacier Hotel in Glacier National Park in 1925. At the time, park concessionaires often required their Blackfeet employees–including bus drivers and telephone operators—to dress in “traditional” clothing to appeal to eastern tourists. Bain News Service, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

“Historian Martha Kohl edited the project, which grew from the MHS Women’s History Matters project marking 100 years of women’s suffrage in the state. Kohl started informally asking people to name 10 women in Montana history.

“Even the best educated seemed to stall at three — Sacajawea, Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin and photographer Evelyn Cameron. But then the stories came of great-grandmothers who homesteaded, widowed mothers who eked out a living in Butte and aunts who served during World War II.

“’In other words, Montanans knew about fascinating women — they just didn’t consider them historical,’ Kohl wrote.”

Martha Kohl (“Montana: Stories of the Land” and “I Do: A Cultural History of Montana Weddings” [see my blog post about that book]) is a historical specialist at the Montana Historical Society.

Many of the essays in the book previously appeared on the MHS webpage Women’s History Matters: 1914 – 2014. The site also contains other references of interest to educators and historians.

According to the San Francisco Book Review, “Each of these stories are short, around three pages or so, and often accompanied by a picture. They tell an interesting story and that is what the contributors bring to life. A story that has been ignored, and if it wasn’t for contributors like these, then these stories would likely be lost forever. Hopefully something like this will bring a closer look to other states and their stories.”

–Malcolm

July 19, 2016

Yes, it has to be accurate even if it’s fiction

I grew up in a journalism family, married a former journalist, worked as a journalist in the Navy, and taught journalism at the college level. So, I watch the daily news with dismay when I see how slanted so much of it is. Consequently, a lot of voters are making up their minds about candidates and platforms that are skewed by out-of-context headlines, manipulated interviews, anchors and reporters who argue with those they’re interviewing rather than asking questions and letting the facts go wherever they go, and panels of experts that are set up to exclude those who don’t agree with the network’s stance.

When I taught journalism, a lot of students came to class thinking that editorials didn’t have to be factual because the words represented a personal opinion (or the opinion of the newspaper). So, as we see on Facebook today where people say all kinds of political things without checking out their accuracy, students tended to say what they thought about an issue without making sure their views were based on the realities of the issue.

Such editorials get chopped a part in news organizations (the good ones) because an opinion piece is so easily discounted when the writer bases his or her thoughts on false facts. Readers who don’t see that the facts are false are, of course, being lied to when the writer feeds them falsehoods in support of whatever agenda s/he has.

What about fiction?

Some people say it’s okay to make up real world facts in a novel because the whole thing’s fiction. With all due respect, that’s one of the stupidest and most inaccurate opinions about writing novels and short stories I’ve ever heard. Obviously, fantasy worlds don’t have to agree with the realities of our world, though the author needs to make those worlds internally consistent. And, we allow some liberties in historical fiction, especially when such novels include conversations between historical people that weren’t witnessed (much less transcribed) by anyone else. Alternative histories, of course, show how things might have gone if a battle went another way or if some other factor was changed, so we don’t expect them to adhere exactly to the historical record as we know it.

Some people say it’s okay to make up real world facts in a novel because the whole thing’s fiction. With all due respect, that’s one of the stupidest and most inaccurate opinions about writing novels and short stories I’ve ever heard. Obviously, fantasy worlds don’t have to agree with the realities of our world, though the author needs to make those worlds internally consistent. And, we allow some liberties in historical fiction, especially when such novels include conversations between historical people that weren’t witnessed (much less transcribed) by anyone else. Alternative histories, of course, show how things might have gone if a battle went another way or if some other factor was changed, so we don’t expect them to adhere exactly to the historical record as we know it.

Most authors don’t have the resources to have expert fact checkers look at every single scene to see if the scene would make sense to somebody who’s actually in the business/hobby/avocation/career that’s the focus of the novel. Major authors even get criticized by policemen, firemen, soldiers, lawyers, doctors and other professions who say that while the novels are page turners, they contain factual errors or ways of thinking that don’t match the realities of those who do the work.

Indie authors have more trouble with this, I think, partly because some of their mentors are telling them facts can be lax in fiction and partly because they don’t have the resources to read more, interview experts, or follow experts around on the job to see how a specific career works. There’s also a lot of pressure these days to write fast and publish fast. Many famous novelists spent (and, in some cases, still spend) many years writing a book. In contrast, a lot of authors try to copy the prolific Stephen King by turning out multiple novels on one year. (King, of course, often includes experts in his acknowledgements that will talk to him because of who he is but who wouldn’t give an unknown the time of day.)

My opinion, is that we owe it to our readers to get the facts right to the best of our abilities and resources. When the facts in a novel are wrong, they are very compelling to readers who have no way of knowing the facts: so it’s easy for readers to assume that the novel more or less is basing its plot on correct police procedures, how courtrooms really work, what a doctor actually might do in the operating room, and on the real beliefs of various minority religions, groups, and factions.

I write about hoodoo and witchcraft, so I am very conscious of the fact that the media, Hollywood, and a lot of commercial novelists perpetrate the belief that hoodoo practitioners are ignorant and that witches worship the Christian devil. Both are false. Yes, the lie is perhaps more exciting in a high-stakes thriller novel, but the result is just as anti-education and anti-truth as an editorial in a newspaper that bends the facts in order to make the opinion look stronger.

Truth is Stranger Than Fiction

At least, that’s what a lot of people say. I always told my journalism students, that writing editorials and essays based on questionable facts was pure laziness and/or an intentional slanting of the piece. I see novels the same way. That is, I don’t think a skilled writer needs to subvert the truth in order to have an exciting plot that evolves through memorable, three-dimensional characters. Most of us have too guess a lot when we write about professions, situations, and places that we’re learning about through research rather than having been in those professions or situations or places. So, we have to accept the fact that no matter how much we check our facts, a “real life” person might say, “it would never happen that way.”

One way to combat that is to interview somebody in the group/profession/avocation you’re writing about. Before doing that, the author needs to do background research so that the questions don’t sound stupid and so clarifications of differing viewpoints uncovered in that research can be made by those you interview. I’ve found a surprising number of experts in all kinds of things that will respond to my questions via e-mail even though I’m not a big name author. I usually ask if it’s okay for me to include their name and/or organization in the acknowledgements section of the book.

One way to combat that is to interview somebody in the group/profession/avocation you’re writing about. Before doing that, the author needs to do background research so that the questions don’t sound stupid and so clarifications of differing viewpoints uncovered in that research can be made by those you interview. I’ve found a surprising number of experts in all kinds of things that will respond to my questions via e-mail even though I’m not a big name author. I usually ask if it’s okay for me to include their name and/or organization in the acknowledgements section of the book.

Another way is to have a friend of colleague who’s conversant in your novel’s subject matter read through some or all of the manuscript. If you have a presence on Facebook, the odds of finding somebody in the profession/avocation/group you’re writing about is certainly higher than our “real-life” circle of friends. Many people like the idea of being beta readers or in reviewing portions of the book relating to their own professions. Another source of information comes from bloggers who specialize in accurately covering their own hobbies and work. They’re often enthusiastic about authors who want to cover their areas of expertise correctly.

Finally, you can avoid some kind of “that doesn’t sound right” issues in your choice of your novel’s point of view. If you write the story in the first person, you’re going to be closer to the protagonist and his/her thoughts than you are if you write in restricted third person. It’s one thing to get procedures and techniques correct–via your research–but much more difficult to get the protagonist’s thoughts correct. How an individual lawyer, policeman, minister, hoodoo lady, doctor or CEO thinks about what s/he is doing is very difficult (unless you have a beta reader from that profession). Needless to say, using a character’s internal monologue about a subject you’re not totally conversant with is more likely to expose gaps in your research than a simple statement followed by the words “he thought.”

When I wrote Sarabande, a fantasy novel with a female protagonist, I found that with some advice from women, I could accurately portray a female character in a believable fashion. One reason for this was that the character came from a different universe and was reacting to our universe; what she might say or do or think was easier to “fake” because she came from another world.

However, when I wrote Conjure Woman’s Cat, about an elderly Negro conjure woman from the 1950s, I didn’t tell her story from her point of view. Why? Because I didn’t think I was capable of getting inside the thoughts of my character. So, I had her cat tell the story. This way, I never had to show her thoughts directly because, quite frankly, I wouldn’t know how to do that in a way that rang true. My wife and I have had cats in our house for an entire married life, so I’m fairly used to how they behave and figure it’s unlikely a lot of cats will read the novella and say, “We would never think something like that.”

We have to use our skills as writers and part-time researchers to get around the things we don’t know when we’re telling a story. I’m interested in super natural subjects, so I’m much more attuned to writing about them than, say, police investigations or espionage. So, I avoid the problem of lack of accuracy by staying away from stories I can’t do justice to and which–when it comes down to it–aren’t my cup of tea to write about.

Bottom line, I think accuracy makes a better novel. That’s my opinion. What’s yours?

–Malcolm

July 16, 2016

Local author experiments with hoodoo and discovers that’s a bad idea

Rome, Georgia, July 16, 2016, Star-Gazer News Service–Malcolm R. Campbell, author of the hoodoo novel Conjure Woman’s Cat, was doing hex research on a dark and stormy night when he went to a nearby graveyard to try out a haint calling spell to see what would happen.

Campbell being bugged by a haint while he tries to write the next chapter of his book.

Haints happened, more than he could shake a stick at (like that would do any good), and while they were generally friendly, they wanted haint tasks: people to scare, places where ghost lights would improve the ambiance, bad neighbors who needed to experience a plague of rabid bull frogs, people walking on lonely roads in search of spooky entertainment.

“I didn’t realize the spell worked until I got home,” said Campbell. “My three cats are always chasing invisible things around the house, so everything seemed normal when I got home from the graveyard. When the cats wouldn’t settle down, I turned off all the lights and was surprised to see a living room full of haints, Most of them threatened to turn on Fox “News” 24/7 unless I kept them busy with exciting haint chores.”

Campbell, who has always believed 100% accuracy makes for better fiction, told reporters during a “fluke rain storm” of flying fish, that trying out the haint spell was bad idea because it didn’t come with any directions for sending the haints back to the graveyard.”

Medicine men, shamans, cops, witches and everyday people with shotguns visited Campbell’s house to try their hand at getting rid of the haints. Nothing worked.

“I have to admit it was fun for a while,” said Campbell, “because when they weren’t out causing mischief, they sat in my Naugahyde recliner and offered tips for the haint scenes in my work in progress. For example, the idea that haints mainly haunt people in cemeteries is pretty much of a myth: more hauntings happen in abandoned Walmart stores than anywhere else.”

Campbell has a hotline with local police to assure them that “his haints” aren’t responsible for every “weird” 911 in Rome and Floyd County.

Security paint at Campbell’s house.

“There’s been so much publicity about the haint infestation,” said Officer Smith (not his real name), “that people just assume Campbell forgot to close the front door and the haints flew out trying to make every night like Halloween. We’ve advised Campbell to keep each haint on a leash so that innocent people won’t get scared and pee in their pants.”

According to one haint who told his story to a local television station, “We haven’t had this much fun since the spiritualism era of the late 1800s and early 1900s when seances were all the rage, Ouija Boards were selling faster than hotcakes, folks wanted to believe they could talk to dead aunts and uncles, and tables all around the country were rocking, rolling and tapping.”

Campbell told the Feds, who came to town to investigate, that the haints were starting to get bored and were planning to leave for Washington, D.C. during the next thunderstorm when energy fields are high and spiritual travel is easier than falling off a tombstone.

“As soon as they leave, I’m buying a fresh can of haint blue paint for the front of my house to make sure they don’t come back,” Campbell told Agents Houdini and Doyle. The agents subsequently confirmed “things are weirder than usual” whenever Congress is in session.

–

Story by Jock Stewart, Special Investigative Reporter.

July 12, 2016

You might just win a Kindle Fire Tablet if you sign up for my publisher’s newsletter

Thomas-Jacob Publishing is starting a newsletter to help its adoring readers keep up with upcoming books and events. Since this is my publisher, I hope the readers are adoring. I’m proud of our catalogue, featuring books by:

Thomas-Jacob Publishing is starting a newsletter to help its adoring readers keep up with upcoming books and events. Since this is my publisher, I hope the readers are adoring. I’m proud of our catalogue, featuring books by:

Malcolm Campbell

Melinda Clayton

Tracy Franklin

Michael Franklin

Robert Hays

Smoky Zeidel.

Okay, moving onto the Kindle Fire Tablet. Click on the graphic below to go to the newsletter signup page. Just a few fields to fill out and then you’re done.

The first place winner of the tablet and the two second place winners of a free paperback from Thomas-Jacob’s list will be selected in a random drawing August 17th.

Good luck in the drawing!

–Malcolm

July 9, 2016

Taking time out for breakfast at Wimbledon

“Deprived of a record-tying 22nd grand slam title in the Australian Open and French Open finals this year, Williams got to No. 22 Saturday by defeating Angelique Kerber 7-5 6-3 in a high-quality Wimbledon final.” – CNN in Serena Williams wins Wimbledon for historic 22nd grand slam title

Yes, I watch FSU football and. depending on the teams, selected games from the World Series. Otherwise, I’m more interested in tennis. Not because I’m any good at it. It’s fun to watch. Recently, I wrote a post about aging authors who are still writing, saying that that gave the rest of us hope. Watching Serena and Venus Williams, at 34 and 36 years of age, playing in a game that requires a lot of stamina and athleticism and favors youth, makes me feel amazed at what people can do who keep in shape and spend many hours a day practicing.

Wikipedia photo

I’ve watched three of Serena William’s Wimbledon matches this week and, while balls hit into the net or just outside the line tempt me to yell at the television set, taking time out for breakfast at Wimbledon serves as a good antidote to my driven approach to my writing. I felt driven earlier this week to work through a hard-to-write section of my work in progress and also to post a blog here about 85-year-old author Edna O’Brien’s stunning new novel The Little Red Chairs (which I’m currently reading).

Time off for tennis has been a better use of my time because–had I asked one–it’s probably just what a psychologist would recommend. Both players in today’s Wimbledon final showed moments of frustration; Kerber rushed her game (and displayed brief moments of panic) on some points and that might have been one reason she didn’t beat Williams this time out. Frustration and panic are bad for a writer, for all of us. Goodness knows, the news this week hasn’t helped.

Time off might look like goofing off, but it’s controlled goofing off that takes one away from a constant focus on work and/or the news rather than turning into a 24/7 habit. Now I can look toward the afternoon feeling like I drank some magic tonic.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of “Emily’s Stories,” “Sarabande,” “At Sea,” and “Conjure Woman’s Cat,” all of which you can learn more about on his website here.

July 2, 2016

The writer has a conjurer

“Perhaps the most succinct evidence for the potent magic of written letters is to be found in the ambiguous meaning of our common English word ‘spell.’ As the Roman alphabet spread through oral Europe, the Old English word ‘spell, which had meant simply to recite a story or tale, took on a new double meaning: on the one hand, it now meant to arrange, in the proper order, the written letters that make up the name of a thing, in the correct order, was to effect a magic, to establish a new kind of influence over the entity, to summon it forth. To spell, to correctly arrange the letters to form a name or a phrase, seemed thus at the same time to cast a spell, to exert a new and lasting power over the things spelled.”

– David Abram in “The Spell of the Sensuous.”

The old adage “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is rather false. Consider the sound-bite phrases and misleading comments in the current Presidential campaign alone that, once said, become gospel. Consider perjury in a courtroom, verbal bullying in a school, highly messaged government-speak, dear john letters, exaggerations on product labels and advertising, and phrases from religious books that are taken out of context. The pen and the voice really are mightier than the sword, the stick or the stone.

In my Sun Singer’s Travels blog, I recently posted “What the hell are these important writers talking about?” Primarily, this was a rant about the obscure (and possibly gibberish) discussions between some writers and some interviewers that make no sense whatsoever to most readers and natural writers. By natural writers, I mean those who discover their stories as they write and, while they usually know the ins and ours of style and technque, they don’t look upon words as requiring a doctoral dissertation to set down on the page in a story.

If a writer creates elaborate outlines, s/he also may write organically while putting words on the page if s/he uses the outline as a rough guide rather than a recipe to be followed precisely. Personally, I think outlines get in the way of the story, though that’s simply my approach.

Hoodoo Reading the Bones

This kit is available from the Lucky Mojo Curio Company.

Traditional conjurers (also called hoodoo practitioners or root doctors) often use a form of divination called “reading he bones” to obtain answers to questions for themselves or their clients. Possum and chicken bones are often used; others (as the picture shows) add other objects such as stones, nuts and shells.

While some conjurers paint or number the bones, assign a meaning to each one–like the meanings assigned to individual Tarot cards–others throw the bones into a small circle drawn in the dirt (see picture here) and listen for the voices of their ancestors who were also conjurers. As with Tarot card readers who are advanced enough to forget the descriptions of each card that they read in a book, conjurers reading the bones may variously say they’re using their intuition, tapping into their inner selves, or hearing the voices of the “old ones” in their lineage.

In short, they use the bones as they view them on the ground as catalysts for channeling information from outside themselves. You can’t do this unless you can step away from the logical “what-ifs” that come to mind when you ask the bones a question. Too much logic destroys a reading because the conjurer is thinking of typical speculative answers to the question (my missing spouse stayed late at work, got in a car wreck, ran away with a co-worker, forgot to tell me s/he had a dinner meeting, etc.) rather than listening for the ancestors or intuition to speak.

Discovery writing

Writing with no outline–or a few sketchy ideas–is often called “discovery writing” because the writer discovers what the characters are going to do and say while writing rather than creating an outline or a list of scenes in advance. Many of us have a general idea what we’re going to do before we start writing. While writing “Conjure Woman’s Car,” for example, I knew that my main character was an old-style conjure woman living with her cat in the Florida Panhandle in the 1950s. I also knew that the Klan was going to do something bad and she was going to respond with hoodoo (folk magic).

Other than that, the story evolved as I told it. In a sense, my muse, my intuition, and even the developing characters “decided” what was going to happen next. When I finished a scene or a chapter, suddenly the thing that was going to happen next came to mind. I supported my intuition by reading a lot about conjurers, spells and related blues songs. Quite often, I’d learn what was going to happen next in my story by the “coincidental” reading of a certain conjuring practice or a historical KKK tactic.

I like to think that when a writer is using discovery writing, s/he is following a practice very similar to the traditional conjurer who throws the ones and listens for the voices of her ancestors for the answer. The conjure woman asks a question and allows the process to create the answer. The discovery writer asks “What If,” listens for the voice of his “muse” and or his unconscious mind and allows the writing process to create the story.

We are, in this way, attempting to cast a spell in the sense David Abram suggests in the quote at the beginning of this post. No, we are not using words to “force” our readers to write us large checks or leave town or change their political beliefs. We’re using words to cast a spell called a story that claims the reader’s imagination from the first word through “the end.”

When the short story or novel comes out well, we’re often praised for our imaginations. That’s okay, but really, our ability is simply to listen and record what we hear. When the story or novel doesn’t turn out well, we probably stepped in the way of the natural process and tried to plan or micro-manage the action down one road or another where it didn’t belong.

At best, we’re conjurers who know as our experience grows how to establish a process that works. Those who read the bones know that they get better results when they wash and dry the bones before throwing them on an animal hide or into a circle. They know not to touch the bones with their hands but to use a stick. Likewise, writers know what conditions make it easier for them to write: some listen to music; others like the background sounds of a natural setting or a coffee shop. Whatever conjurers and writers typically do when they work evolves into rituals that support hearing the true answer to the question or hearing where the story needs to go.

Answers and stories live and breathe on their own. If we have a talent, it’s being able to keep our of the way.

–Malcolm

I invite you to stop by my “Conjure Woman’s Cat” website for more information about my 1950s Florida folk magic novella as well as my other books.

June 27, 2016

Let’s hope we’re all still writing when we’re old and grey

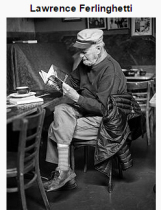

“Tall and agile at 97, with a neatly trimmed gray beard and oval tortoise shell glasses that magnified his glassy blue eyes, Mr. Ferlinghetti could pass for a man in his 70s. He still writes almost every day — ‘When an idea springs airborne into my head.’”

– Alexandra Alter, “A Literary Bromance, Now in Its Sixth Decade,” in The New York Times

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, whose poems I feel like I’ve been reading for several lifetimes, is polishing up a memoir/novel after years of badgering by his 96-year-old literary agent Sterling Lord. Their ages give me hope.

Wikipedia photo

Hope. because it’s nice to live that long. It’s nice to still have words and a voice at that age and keep on writing. It’s nice to see that it’s possible to have a friend and colleague you’ve known since the beat-poet era of the 1950s. It’s nice and its hopeful to think that when one has a lot of ideas s/he wants to put into writing, it just might be possible to do it.

Not that I think I can equal Ferlinghetti’s 50 volumes of poetry by writing 50 novels. I’m realistic. Unlike Stephen King, who writes most of his novels in a couple of months,

I’m a lot slower. Ferlinghetti is, like Herman Wouk, (now 101) in that group of writers about whom people say, “Gosh, I thought he probably died years ago.” I don’t know how Ferlinghetti, Lord and Wouk react to those sentiments.

Doesn’t matter, really. It’s nice to know that if they ever hear people say that, they’re still around to say “I’m not only alive and kicking, I’m also alive and writing.” (There’s an interesting Herman Would article here.)

P hoto from Herman Wouk’s web site.

Writing, I think, is one of those occupations that not only keeps people alive and kicking, it wards off the morbid maybe I should cash in my chips feelings a lot of people seem to get when they become senior citizens. Fortunately, writing doesn’t require heavy lifting or many other kinds of physical stamina that are usually gone by the time people each 96, 97 and 101. In fact, reading and writing are said to help develop people’s brains and minds when they’re young and keep brains and minds more facile and creative when they’re old.

What’s not to like?

Perhaps some of us will say everything we want to say before we’re old and grey. We’ll spend our years traveling. Tending our bees or our roses. Reading as much as we can. Enjoying family and friends and everything else with agile minds (due to the reading).

It’s hard to imagine not writing, even if we write only for ourselves and stash all those poems, novels and essays into basement file cabinets. When I was young, I once visited my 100-year-old aunt who not only remembered dozens of stories from crossing the country in a covered wagon, but also knew everything about current day books, politics and culture. I wondered how it felt to be 100. Mainly, I wondered if I’d be a totally different person. I’m not a hundred, but as the years pass, my greatest surprise has been that age doesn’t change who one basically is–yes, we might have put away many of the thoughts and hobbies of youth, but still, we begin our days with hopes, many of which are similar to the hope felt when we were kids and beginning our first jobs and seeing our children born.

The writing gets better with age. Mostly, that’s just practice and experience. If you write for 60 years, you’re bound to get better. Most writers look forward to getting better even if they have great success when they’re young. We want to get better because no matter how well a book or a poem turns out, we see that it never quite matches the dreams we had for it when we wrote the first draft.

Like opera singers, we may lose some of the raw, unbridled power of our youth. There’s always more to be said, though. The fates are kind to give us time to say it.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of “Sarabande” and “Conjure Woman’s Cat,” both of which are available in paperback, e-book, and audiobook editions.

June 22, 2016

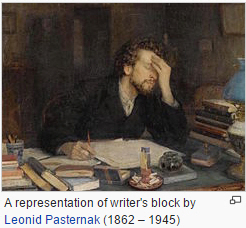

Sometimes writer’s block gives you a chance to figure things out in your work in progress

I knew before life got derailed in April and May with unexpected trips to the hospital for unplanned surgeries, that a new character was about to appear in my work in progress, a guy named Rutherford “Rudy” Flowers. I also knew he was going to show up in the next scene in the book.

But after the surgeries–and a reasonable recovery period–I couldn’t write that scene. Uh oh, writer’s block. I even knew what critical piece of information he planned to tell my protagonist. But still, I hadn’t figured out the character, and that meant–well, the writer’s block.

Wikipedia photo.

This is a potential problem for those of us who write with no outlines and with no nailed-down sequences of events in mind for our novels and short stories. Every once in a while, something is supposed to happen. We don’t know why, and we can’t move until some of that why comes to mind.

When this happens to me–as it just did–I tinker around the edges of the book without writing anything. Since it’s set in the 1950s, I can always go more research into slang, clothing, events, foods and products of the time period. Some of what I learn actually comes in handy. This tinkering, though, ultimately unlocks my writers block. It’s odd, I know, but research often brings things to light that I wasn’t looking for, things that turn out to be vital to the story.

If you believe in muses–and I do–it’s almost as though the muse has put a hex on my being able to open the Word file with the story in it until I figure out there’s something I need to know before I go back to it. Now that I’ve found that something, I see there were clues to it all over the place that I just wasn’t noticing. Now I know who Rudy Flowers is and how vital he and his mother are to the story.

Writer’s block is usually aggravating, especially when your publisher is waiting for you to hand in the manuscript. I’ve never been able to force myself out of writer’s block like those writers and teachers who say it’s better to sit down and write anything at all rather than to write nothing. I’m better off writing nothing (not counting blogs and tweets) than trying to force a story to happen when the words aren’t there.

If you’re a writer, how do you face writer’s block and finally get back to work? As for me, I’m back to my story because the muse has come home.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of “Conjure Woman’s Cat” and “Emily’s Stories.”