Mary Gottschalk's Blog, page 7

February 25, 2014

The Book Review is Dead. Long Live the Book Review.

Would it surprise you to learn that, on the eve of the release of my first novel, I am peering closely at the business of book reviews? What I observe, as both an author and a reader, is not re-assuring. In fact, it’s downright perplexing!

Would it surprise you to learn that, on the eve of the release of my first novel, I am peering closely at the business of book reviews? What I observe, as both an author and a reader, is not re-assuring. In fact, it’s downright perplexing!

Much ink has been spent in recent months on the decline of professional book reviewers, including several articles in the New York Times and a thought-provoking blog by author Susan Weidener (see links below). The decline reflects both a reduction in the number of publications that offer book reviews (e.g., many local newspapers no longer offer book reviews) as well as a decline in the number of professional book reviewers.

As a reader, this phenomenon is disturbing, as it makes it harder to determine which books I’d like to read. But as an indie author, it is not a primary concern, as I would not expect to be reviewed in the Atlantic Monthly or The New York Review of Books, unless I had already achieved very considerable market awareness.

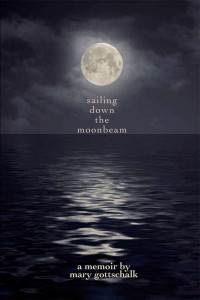

No, my concern is the book reviews on Amazon and Goodreads, the two primary places where readers provide feedback. Based on my experience with my memoir, Sailing Down the Moonbeam, the system is flawed.

Of the three dozen or so reviews on Amazon, more than half are 5-star, the highest ranking a book can get. I am, of course, thrilled to have them, particularly those that provide thoughtful commentary on the quality of my writing, the structure of the memoir, and the extent to which the reader experienced a “shiver of recognition.”

But I am puzzled by the number of readers who, in effect, have ranked me alongside Barbara Kingsolver or Sue Monk Kidd. I am a good writer, but not that good.

The problem lies, in my view, in the reliance on a simple 1 to 5 star ranking, with input from a self-selected segment of readers whose qualifications as critics are rarely known and whose motives are often suspect. This system allows readers (including personal or professional friends of the author) to make public judgments about a book without necessarily providing—or even having—any specific criteria or rationale for their opinions. Such reviews may puff up or deflate the author’s ego, but do little to help readers determine whether a book will be of interest or whether it is a genuinely good read.

Take, for example, a 5-star review that says only “I loved it” or a 1-star review that says only “I hated it.” What does a reader learn from this? I’d like to know if the reviewer only reads short books, or only reads memoirs, or only reads sports stories. I’d like to know if the reviewer prefers action-oriented adventures or character-driven stories. I’d like to know whether the reviewer sticks to familiar topics and settings or enjoys exploring challenging new environments. I’d like to know if the reviewer loved the writing, or a liked a good yarn despite mediocre writing or liked the story but hated the writing.

The issue is further complicated by the reluctance of many authors (myself included) to put anything less than a 3-star review on Amazon. How, in this environment, does a reader identify a poorly written book with a thin plot and/or bad editing or one that is a real gem.

Goodreads appears, at first glance, to provide a more reasoned approach, as the preponderance of the Moonbeam reviews are 3-star or 4-star. The problem here is that Goodreads reviewers can “rank” a book without so much as a word of explanation as to the basis for the ranking.

I am stuck with the system as it is, but I wonder how you, as a reader, think about reviews on Amazon and Goodreads. Do you rely on these reviews? Do you write reviews? How would you change the system?

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Suggested Reading

Susan Weidener: What’s Up with Book Reviews?

New York Times, Colin Robinson, “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Reader”

New York Times, Maureen Dowd, “Bigger than Bambi”

The New Yorker, Lee Siegel, “Burying the Hatchet”

The post The Book Review is Dead. Long Live the Book Review. appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

February 17, 2014

Reaching My Reader — Part III

Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s. ~ Stephen King

[image error]Several months ago, I blogged about the challenge of writing on a controversial subject—sexual fluidity—for an audience that spans three generations. As I noted then, many of the words that describe the spectrum of sexual relationships described by Alfred Kinsey a half century ago carry very different connotations depending on whether you are age 20, 40 or 60.

In retrospect, the challenge was more easily met than I anticipated. Because the theme of A Fitting Place is the growth that occurs when you step outside of your comfort zone, my interest was in how Lindsey Chandler deals with change, not with social constructs of gender or sexual identity.

In this context, my camera is trained on the day-to-day interaction between two idiosyncratic women who are searching for new ways to cope as they struggle with failed marriages and distraught children. What matters is their ability to provide support, affection and physical comfort along the way. They see no need to attach a label—such as lesbian, bisexual, or sexually fluid—to their relationship.

In a sense, the concept of sexual fluidity is of much more interest to me as an author than to my characters. In recognizing that sexual attraction, particularly for women, is often influenced more by the person than the gender, the concept allows me to discuss the dynamics of rebound relationships without getting ensnared in the “chick lit” genre.

The situation seems far more problematic now that my focus has shifted to marketing, to getting this book into the hands of readers interested in the options available to women who have left, not always by choice, a long and stable relationship.

Suddenly, I am in the world of sound-bites, of pithy phrases, of zingy one-liners. To use a cliché, I feel like I am between a rock and hard place.

The term “sexual fluidity” has only recently come into non-academic usage, and is unlikely to resonate with a large audience. Marketing copy that uses “lesbian” or “bisexual” implies something about my characters that may or may not be true, depending on the reader’s definition of those terms. While the labels don’t really matter to the story, leaving such terms out of my marketing materials may result in disappointed or angry readers who do not wish to read about unconventional sexual behaviors.

A Fitting Place addresses the challenges of rebound relationships, and their implications for all of us. The trick is to find a way to make an unconventional story appealing and accessible to a broad range of women.

Hmmh ? ?

My series on themes in A Fitting Place continues. I welcome your comments on this blog. If you would be interested in contributing to the discussion with a guest blog, please check out my guidelines here.

The post Reaching My Reader — Part III appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

February 10, 2014

Secrets Unravelled

My blog this week offers a very different perspective on secrets. My guest, Philipa Rees, offers the view that some secrets are well-kept and may be a source of strength.

Secrets are of many kinds, some buried beneath a significant event, some like fungi that spore underground and mushroom when the light is right to poison the unwary. On the surface my family seemed to have no secrets. That was the doing of ‘Marna’, my galleon grandmother, whose high disdain and certainty of her natural superiority sailed the high seas of our misfortunes, trimming her sails to every wind, and charting our independent course of proud poverty.

It was only after her death that I learned her secret, which explained everything. Triumphing over the secret was, I now see, her raison d’être. It’s why independence of mind and courage was all she fostered and cared about, why we were all shaped by that ancestral thorn.

Thinking about this guest blog, it occurred to me that secrets are usually thought to be destructive. In her case, by contrast, I see the transformative potential of a closely guarded secret. I suspect without her secret to stiffen her spine, my grandmother, an educated woman with little to do but to direct African maids and entertain tedious Colonial grandees, would have sagged under the weight of boredom.

The secret? Her mother was murdered, stabbed to death as she slept, though she must have struggled before the gruesome end. That explosion of violence was witnessed by a small boy of three, my grandmother’s son, in the corner of a dark room, clinging to the bars of his cot. As the two Zulus who committed the act turned to leave, they caught sight of him, wide-eyed with terror. One said, ‘Now we must kill him too.’

‘I can never kill a child’ said the other. Putting down a bloody knife, he placed the small boy on his back, covering him with a blanket. ‘Sleep gently little master’ he said.

I can already hear you saying ‘Now we are into fiction, how could she know that?’ I know because that child was my uncle and it was his testimony that hanged the two murderers. He was the youngest witness ever to send men to the gallows. Zulu was his first language, but after the trial he never spoke of it again, and nor did my grandmother.

I learned the facts, twenty years after my grandmother’s death, from a stranger passing through a Wiltshire village pub. An extraordinary synchrony, it seemed we were plucked like migrating birds, perched momentarily together to complete each other’s memories. He was a rural post boy, detained at every doorway to hear the details of torture. Not just the murder, but the torture of my grandmother, beaten as a toddler on the soles of her feet with thorn branches, or tied to a chair with cotton thread for hours. Both the murder and my unlikely hearing of it convinced me that everything has its deep thread of purpose.

So, it turned out that this murder liberated my grandmother from a deeply sadistic mother. For her, God had intervened. The murderers, farm workers who came to kill their torturer, had come for nothing but a sacrificial service. To save the other farm workers cowed by the mistress of their lives, they had drawn the short straws round a kraal fire, saviours for the rest.

That harrowing liberation had certainly traumatised her small son and bonded a relationship no one else could share. Marna’s first husband, more interested in flying than farming, flew away (literally, in a canvas biplane sewn on her Singer), leaving her free to marry Heli, my grandfather. Heli was an educational missionary who escaped the social prison of Northern working-class Britain. From a dutiful Methodism and a clerical desk, he set sail for Natal, to ride through hills of grass, master Zulu, and take upon himself the untapped field of African education.

Oh, brave new world.

My grandmother was at home in the world he sought to make his own, with nothing but a joyful and supportive liberty to invest. Her small son took Heli’s name; the births of my mother and my aunt soon followed. Photographs reveal that the sails of my grandmother filled, and floated above everything thereafter. She had a unique perspective on both life and death; nothing small ever mattered, not money, not clothes, and least of all the opinions of others. Conformity had no place in anything she did: on a beach, this grand Victorian stripped to a petticoat; at pompous gatherings she dissolved with laughter.

As an only child with a bereft and hard working mother, I saw Marna as the early centre of my existence. I adored her constant irreverence. There was nothing she feared, except that her children would settle for less than confident liberty. Something deep and constant lay at the root of what she gave to us—the permission to be exactly what we were, without apology. I am sure that was her dark secret translated into strength and celebration.

From her I learned almost everything I still value. Her maverick genius for finding the unique and amusing has sharpened all the characters I like to spend time with as a writer. My characters are all solitaries; even when, historically, they were famous and important. I have chosen to seat them with the monosyllabic labourer, just as she would have done.

Philippa’s early life was spent in remote parts of Southern Africa, often on safari. At University, she studied science, theology and literature and graduated in Psychology and Zoology under the seminal palaeontologist Raymond Dart and the father of Embryology B.I Balinsky.

Philippa’s early life was spent in remote parts of Southern Africa, often on safari. At University, she studied science, theology and literature and graduated in Psychology and Zoology under the seminal palaeontologist Raymond Dart and the father of Embryology B.I Balinsky.

She has recently published the ‘book that wrote the life’. Involution-An Odyssey (Reconciling Science to God) retakes the journey of Western thought to discover an alternative to Darwin’s evolution. Her other published work is a poetic evocation of the sixties ‘A Shadow in Yucatan’

Writing apart, she has lectured to University students, built a music centre, and raised four daughters. She lives in barns she converted in Somerset, England.

Her blog can be found at http://involution-odyssey.com/blogscribe/

She would welcome contact at philipparees7@gmail.com or through Twitter @PhilippaRees1

Website: http://involution-odyssey.com/

If you are interested in participating in this discussion about themes in my novel, A Fitting Place, please check out the guest blog guidelines here.

The post Secrets Unravelled appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

February 3, 2014

Dad’s Dilemmas

In the ongoing discussion of themes from A Fitting Place, another perspective on keeping secrets comes from Paige Adams Strickland, an author and teacher, who writes about a father and daughter, each struggling to come to terms with a secret.

Paige’s story:

While I was growing up, my father was loving but always conflicted about everything.

While I was growing up, my father was loving but always conflicted about everything.

His work life was love-hate. He enjoyed sales and marveled in new technologies that would change the world, but was annoyed by the stodgy, old cronies who made the rules and the young university grads who, having dodged Vietnam, still landed executive positions right out of college.

At home, he hated religious dogma and hypocrisy but worried what would the neighbors think. He conformed to the norms, but grumbled at the phoniness. He enjoyed the arts, and swore that all sports were rigged. He had little faith in doctors and the clergy, but was intrigued by aliens, horoscopes and other unexplained phenomena.

At first, we thought Dad was just quirky and unpredictable. And then we learned that he had two unresolved “secret” issues. One he gradually accepted and embraced. The other embraced him.

When he was 60, Dad finally came out as gay. He lived in an era when it was forbidden in his corporate lifestyle. Once he retired and moved to Florida, 1,000 miles away from most of the rules that had governed his reputation, he slowly stepped away from his closet of conflict and shame.

He hid it from his family for a while longer in fear that we’d not only lack understanding but also completely reject him. It took years to convince him that the only reason we kids were upset was because he did the one thing he insisted we never do: lie.

Dad was very much a fan of “be yourself,” but he struggled to follow his own advice.

That hypocrisy drove me crazy. During this time, I was also “coming out” as a once ashamed adoptee and decided to search for the truth about my birth family and circumstances surrounding my adoption. I could not lie about who I was to my friends or myself any longer, and it was a huge relief when my dad began to open up about his need to follow his instinct and pursue a lifestyle in which he could find peace and pleasure. When he stopped lying and pretending, we found common ground where we could share jokes and more meaningful discussions without barriers and secrets.

His second issue was alcohol. It’s hard to know if it was a result of his angst as a gay man in conservative, upper-middle class society or if the alcoholism would have been present regardless. He’d built his professional success over martini lunches with bigwig clients and company vice-presidents. He was reared in a culture where drinking made him more of a man and enhanced his competitiveness. Alcohol allowed him to win deals and land contracts.

He didn’t drink for pleasure and fun. He did it to earn a better living, impress people and divert their attention away from his “gay” mannerisms and preferences. Sadly, coming to terms with his new identity and finding a partner who brought him happiness and acceptance did not stop the excessive consumption of hard liquor.

He was still my dad: The guy who loved making chocolate fudge on autumn Saturday afternoons and riding big roller coasters in June, who took us swimming and shell-hunting at the beach, cussed a blue streak if we made a mess in his car, grilled the world’s best hot dogs on Labor Day and cheered the loudest at band concerts and plays.

He loved music and art, cried at movies and when the first Space Shuttle launched. He provided well for his family, in a Walter Mitty kind of way because he feared he had a better chance if he could hide his reality behind liquor and the illusion that his lifestyle was straight.

Dad’s been gone since 1996, but it still feels like yesterday. I wish he could have met all his grandkids and been able to ride a few coasters, swim a few swims and grill a few ‘dogs for them. He’d give standing ovations for all of their plays and recitals and dance like a fool at their weddings.

My dad was a smart man of mixed messages but forward thinking in a time when people weren’t ready.

Conflicts and all though, I wish he were here.

Paige Adams Strickland lives in Cincinnati, Ohio. She is married with two daughters. Her first book, Akin to the Truth: A Memoir of Adoption and Identity, is about growing up adopted in the 1960s-80s (Baby-Scoop Era) and searching for her first identity. It is also the story of her adoptive family and in particular her father’s struggles to figure out his place in the world while Paige strives to find hers as a young adult. After hours she enjoys spending time with her family and friends, her pets, reading, writing, teaching Zumba ™ Fitness, gardening and baseball games.

Paige Adams Strickland lives in Cincinnati, Ohio. She is married with two daughters. Her first book, Akin to the Truth: A Memoir of Adoption and Identity, is about growing up adopted in the 1960s-80s (Baby-Scoop Era) and searching for her first identity. It is also the story of her adoptive family and in particular her father’s struggles to figure out his place in the world while Paige strives to find hers as a young adult. After hours she enjoys spending time with her family and friends, her pets, reading, writing, teaching Zumba ™ Fitness, gardening and baseball games.

Links for Paige:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AkintotheTruth

Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=106898209&trk=nav_responsive_tab_profile

Twitter: https://twitter.com/plastrickland23

WordPress: http://stricklandp.wordpress.com/

If you’d like to join the discussion about themes from A Fitting Place, please contact me here.

The post Dad’s Dilemmas appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

January 27, 2014

Nostalgia, Neophilia and Now

Last week, I confessed to neophilia—a preference for variety in daily life, a high tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty, as well as a love of a challenge. But being a neophiliac does not preclude moments of considerable nostalgia.

Last week, I confessed to neophilia—a preference for variety in daily life, a high tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty, as well as a love of a challenge. But being a neophiliac does not preclude moments of considerable nostalgia.

Unfortunately, nostalgia sometimes gets a bad rap. Merriam-Webster defines it as a “wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to some past period or irrecoverable condition.” This negative perception undoubtedly stems from the Greek roots of the word—nostos (‘return home’) and algos (‘pain’).

The implication here is that if you tend to reminisce about the past, you’re probably not a lover of the new. In fact, I’d argue that nostalgia is critical to being a lover of the new. But my view of nostalgia is less a longing to return to the past than an appreciation for how your past has shaped who you are today.

Support for this point of view comes from Susan Krauss Whitbourne, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. In a 2012 article, What’s So Nice about Nostalgia?, Whitbourne argues that the experiences of your teens and early 20’s are critical to the person you become later in life. In her view, these are the years when most people begin to forge a sense of identity.

Whitbourne says that after age 30, “We shape and re-shape our life stories, reworking the narrative in a way that enhances the way we feel about ourselves now.” She adds that “dipping into the past to remind you of how you’ve coped with previous life stresses can help you strengthen your confidence in dealing with what you’re facing now.”

Whitbourne provides a helpful frame for my own experience growing up with a mother who mocked most of the things I cared about and a school environment in which I was bullied on a regular basis. It was clear that I did not fit in; the harder I tried, the worse things got. By age 16, I was desperate to escape.

I went off to college, and then to New York to work in finance. I escaped my mother and the school bullies, but I could not escape the inner child who expected criticism at every turn. My solution was to keep moving on—new jobs, new friends, new adventures—before “they” could discover what I presumed my mother and school mates already knew.

I didn’t start out as a neophiliac. I started out a scared young woman desperate to escape the mockery and criticism of her childhood. But serendipity played a large role in making me one.

Thinking about that serendipity is where nostalgia comes in. I always had an analytical and questioning mind. I always liked solving problems. I always hated routine, and was eager to take on a new challenge. Had my career started out, as so many do today, in a routine job with a boss who expected me to follow the rules, I suspect I would not be a lover of the new but simply a woman still trying to escape the inner bullies.

In fact, who I am now—a lover of the new—reflects, in very large measure, the fact that my early employers—all men—encouraged me to explore new ideas and take on new challenges. This was indeed serendipity at a time when finance and banking were even more of a man’s world than today. I have no desire to return to those days, but I don’t ever want to forget them.

What role does nostalgia play in your life? What are you nostalgic about?

To read Whitbourne’s article, click here.

This continues the series on themes that are significant in my upcoming novel, A Fitting Place. If you would be interested in doing a guest blog on one of these themes, click here.

The post Nostalgia, Neophilia and Now appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

January 20, 2014

Neophilia: Love of the New

I learned a lovely new word—neophilia—over the Christmas holidays. Based on my youthful exposure to foreign languages, I knew immediately it was a word I could find a use for. Neo is the Latin for “new.” Philia is the Greek for love, particularly love relating to ideas or activities.

I learned a lovely new word—neophilia—over the Christmas holidays. Based on my youthful exposure to foreign languages, I knew immediately it was a word I could find a use for. Neo is the Latin for “new.” Philia is the Greek for love, particularly love relating to ideas or activities.

There you have it: love of new things. My handy Merriam Webster dictionary confirmed my off-the-cuff translation. Neophilia is the “love of or enthusiasm for what is new or novel.”

The word neophilia allows me to put a positive spin on an aspect of my personality that has been problematic for years. For most of my adult life, I’ve been relatively comfortable living in a world of uncertainty. Uncertainty about the weather. Uncertainty as to where my next consulting job would come from. Uncertainty about the nature of God or the existence of an afterlife. Many of my friends think of me as a risk-taker.

Having spent most of my career in finance, my concept of risk came from the study of statistics. Risk, from that perspective, is the likelihood that the outcome of an investment decision will differ from your expectations. That difference can be positive or negative, a gain as well as a loss. As a risk-taker, I could have a bad experience. But I might also have a good one.

In the everyday world, however, risk-taking is almost always viewed as bad or unpleasant. Recognizing this bias, I tend to describe myself as judicious or thoughtful, as someone who takes “reasonable” risks where even a negative outcome has some compensating benefits.

Invariably, people shake their heads, unpersuaded that being judicious, thoughtful, or reasonable is sufficient to make risk-taking appealing. But over the years, I’ve found that a lot of those head-shakers share some or all of the characteristics that qualify me a risk-taker.

I’m relatively adaptable in the face of change, whether imposed by people or by Mother Nature. (I admit I do get grumpy when I think decisions have been made carelessly or without thought.)

I enjoy the challenge that comes with new customs and alternative approaches to getting through a day. It is why I was so willing to give up my career and set sail around the world on a small boat at age 40. It is why I was thrilled to be a caregiver on a trek in high Himalayas at age 69. Neither expedition was a complete success in conventional terms, but both were life-affirming journeys from which I am still reaping the rewards.

I abhor tasks that are repetitive or routine. I will do almost anything once, most things twice, a few things three times, and after that, I start looking for something new to do. This is why I loved being a consultant. Each client company was unique, and I spent most of my time on the job learning about a new culture, a new array of products, a new set of goals and strategies, and of course, a new stable of personalities. Most days I went to bed knowing more than I knew when I got up that morning. And once I’d learned enough to complete the assignment, I was on to a new client. I never got bored.

How do you deal with uncertainty? Do you love learning and want to continue to grow intellectually and emotionally? If so, welcome to the world of neophilia.

This blog continues the series of discussions on key themes from my upcoming novel, A Fitting Place. If you’d like to join the discussion, please contact me here.

The post Neophilia: Love of the New appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

January 13, 2014

Old Bones: The Cost of Keeping Secrets

The cost of keeping secrets is the focus of my blog this week. This discussion has been contributed by historian and writer Frances Susanne Brown, who explores the impact of secrets for those who do not know quite what the secret is.

Skeletons in the Closet

The phrase came into use in 19th Century England and originally referred to hereditary or contagious disease. Folks whose families suffered or even died from an illness preferred to keep the information private, lest they be shunned or judged in social circles.

The phrase came into use in 19th Century England and originally referred to hereditary or contagious disease. Folks whose families suffered or even died from an illness preferred to keep the information private, lest they be shunned or judged in social circles.

From this, the idea of a hidden body found its way into Gothic fiction, such as in Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Black Cat. Author William Makepeace Thackeray used the exact phrase “skeletons in closets” in his novel, The Newcomes: Memoirs of a most respectable family (1855). Occasionally, the skeletons of unwanted infants are still found hidden behind the walls of old houses.

Notice here the emphasis on the social repercussions associated with keeping secrets. The basis for keeping certain information out of the public eye seems directly linked to the notion that it will preserve a family’s reputation, or their status in society.

But keeping secrets has a cost. Like rotting corpses, these secrets fester, lingering as never-healing wounds. And secrets, we all know, seldom stay confined to one person. If they are shared with other family members, particularly children, the repercussions multiply exponentially.

In January of 2013, Psychology Today published an article entitled “Keeping Secrets” by Frederic Neuman, M.D., Director of the Anxiety and Phobia Treatment Center in White Plains, N.Y. He found that phobias in adults are commonly traced to a secret their parents told them to keep. These range from the trivial – we have wine in the house – to the more profound – don’t tell anyone Daddy has been treated for alcoholism. Dr. Neuman claims that by telling our children to keep secrets, we teach them shame, inferiority, vulnerability, and fear.

Other research reveals that a secret represents an actual, physical load we bear. In May 2012, Tufts University psychology researcher Michael Slepian concluded, “The more psychologically burdened the participants were, the more physical burden they experienced.” This study was based on cognition, the theory that the body and mind work together to process information. Slepian asked participants to recall a secret – either big or small – and then presented them with a picture of a hill. Those with big secrets perceived the hill as much steeper than those whose secrets were, in their own opinion, of minor importance.

Don’t Tell Anyone

These three little words can actually affect our health, and make our everyday physical tasks more difficult. They can shape—or warp—a personality, cause phobias, and, ironically, impose as much damage on family members as the original public judgment or scorn they were trying to avoid. A particularly frightening realization is that a family “skeleton” can be passed down, like a genetic defect, even if the actual secret is never disclosed.

How do I know this? I have lived it.

I grew up with a crippling lack of self-confidence and a poor body image, perpetually plagued by a fear of failure. It was as though a huge chunk of me was missing or inferior. Although I had no physical deformity, I felt emotionally disabled. It was not until I was in my fifties, had raised a family and buried both parents that I discovered the cause. My mother’s birth certificate, which I had never seen, allowed me to embark on an ancestry search.

The secret I uncovered has explained me to me. My mother’s “skeleton” wasn’t even her own – it was my Grandma who said don’t tell anyone. I believe her family secret made my mother timid, self-conscious, and afraid to assert her independence. She never shared the secret with me, and tried all through her life to protect me from knowledge that she felt would be harmful. Evens so, its effects, like the miasma of a rotting corpse, clung to her. Unintentionally, she passed those damaging effects on to me.

Every family tree is partially constructed of skeletons. We teach our children to treat others with honesty, respect, and acceptance, but how can they go out into the world and embody these concepts if we have also taught them secrecy? How can we hope for them to enjoy full, happy, loving lives if they secretly harbor shame, guilt, and fear?

The cost of keeping secrets can be profound, and can affect future generations, even if we believe the skeleton is safely, and permanently, hidden in the closet.

Frances Susanne Brown grew up in New York State, earned her MFA from Lesley University, and presently resides in Massachusetts. Her historical articles have appeared in Herb Quarterly, the Family Chronicle, and Renaissance Magazine.

Frances Susanne Brown grew up in New York State, earned her MFA from Lesley University, and presently resides in Massachusetts. Her historical articles have appeared in Herb Quarterly, the Family Chronicle, and Renaissance Magazine.

Her memoir, Maternal Threads, is due out in 2014 from High Hill Press. You can find her on Twitter @francessbrown, on Facebook, at www.francessusannebrown.com and .

January 6, 2014

Mindfulness in the New Year

Mindfulness is very trendy these days.

Mindfulness is very trendy these days.

In the last few months, Google Alerts has delivered several references a day to blogs that explore the application of mindfulness to everyday life. A recent sample included holiday eating, parenting, office management, career planning, reading comprehension, and— this one got a belly laugh from me—using a smartphone.

In my view, most of these advice-giving essays miss the point. While there is considerable evidence that an attitude of mindfulness can have a positive impact on one’s life, particularly in terms of reducing stress, mindfulness is not a tool, but a state of mind.

It is a state of being in which you are consciously and intentionally present in the moment, in which you observe your situation non-judgmentally, without regard to how the present moment relates to the rest of your life. It reflects a recognition that the past no longer exists, that the future is both unknown and largely out of your control.

I first ran into the concept of mindfulness twenty years, at the top of mountain in India. I was attending a month-long philosophy class at the Tibetan Library in Dharamsala, the home of the Dalai Lama. As someone who tends to be highly analytical, I was charmed by the idea of simply being present in the moment, whatever that moment happened to be.

The concept of mindfulness resonated all the more because it offered a philosophical explanation for the unusual degree of contentment I experienced during the eight months my husband and I had spent crossing the Pacific Ocean on a 37-foot sailboat. Our pace of travel and our ports of call depended on the wind and the weather, both completely out of our control. In those pre-cell phone and pre-GPS days, we had very little contact with the outside world. We had left family and friends behind, and had no idea what lay ahead.

Beyond brushing my teeth, fixing meals, and trimming the sails when the wind shifted, there was very little I had to accomplish. When I wasn’t reading or sleeping, I watched the multi-textured sea beneath us and explored the star-filled skies above.

I savored those moments. The bronze-and-gold highlights on the water’s surface as the sun peeked above the horizon in the morning. The dancing lights cast on the black sea by the moonlight. The white stripe painted across the sky by the Milky Way. The surprisingly visible “black hole” in the sky near the Southern Cross. The high-pitched whine of our stern-mounted reel when we caught a fish. The alternating sensation of warmth and coolness as the heeling of the boat moved me from full sun to the shadow of the sails.

I was, for much of those eight months, present in the moment. I was mindful, not because I aspired to be, but because that was pretty much all there was to do.

It was a lovely way to live.

But being in the moment proved harder to do once I returned to the world of work, travel, family and friends. It has been particularly hard during the past two years, when I have been intellectually and emotionally committed to finishing my novel, A Fitting Place. But the book is now done, with publication planned for the spring.

There are lots of “tasks” that remain to be done before then, but none that require the intensity of focus that writing a book took. I am consciously avoiding including any of these tasks in my goal for 2014.

Instead, my New Year’s resolution is to simply “be present” as often and as intentionally as I can.

I think I won’t call it mindfulness.

Happy New Year to all my blog readers. The discussion of themes that are relevant to my forthcoming novel will resume next week.

The post Mindfulness in the New Year appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

December 19, 2013

Holiday Greetings

Best wishes for the holiday season and for a Happy New Year to my readers, contributors, and supporters.

Best wishes for the holiday season and for a Happy New Year to my readers, contributors, and supporters.

I’m taking a break from social media for the holiday, but will be back again after New Year’s with more thoughts on issues relevant to my novel, A Fitting Place.

The post Holiday Greetings appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.

December 11, 2013

The Time is Now

Do you have someone on your holiday gift list that has a Kindle, enjoys memoir and/or loves the sailing life? Or have you been thinking about reading it yourself?

Do you have someone on your holiday gift list that has a Kindle, enjoys memoir and/or loves the sailing life? Or have you been thinking about reading it yourself?

If you want a great deal on a great read (“a memoir written in stereo” according to one review), the time is now! Sailing Down the Moonbeam is on sale all this week:

December 10th & 11th — $1.99

December 12th & 13th — $2.99

December 14th & 15th — $3.99

On December 16th (8am California time), it returns to normal price ($5.99)

For additional holiday book deals, check out the Kindle Countdown program.

And remember, the time is now!

The post The Time is Now appeared first on Mary Gottschalk - Author.