Kate Meadows's Blog, page 5

September 8, 2021

Good Writing is Practice. Practice is Discipline.

A sense of trepidation washed over me as I stared at my flute case on the table. There it lay, this beautiful, gleaming instrument, this precious sidekick that had once opened doors for me to see the wider world. Together, we had traveled to Pasadena, CA, for the turn-of-the-millennium Rose Bowl Parade and to Washington, D.C. for the 2001 Presidential Inauguration. Together, we had twice traveled across Europe. This instrument of mine had floated music in cold and grey European cathedrals that had withstood centuries of war and weather. It rang out on street corners packed with parade goers and in cavernous concert halls. Its notes filled mirrored practice rooms where I spent hours building my chops, perfecting my embouchure and strengthening my fingering precision through sixteenth-note runs.

Six years later, there it sat, silver and smudgy with fingerprints, just as I had left it the last time I put it away. In the years since college, life happened: I got married, went to work, had children. Carving out an hour a day to practice my flute was out of the question now. In fact, I hardly practiced at all.

“my FLUTE” by ken2754@Yokohama is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“my FLUTE” by ken2754@Yokohama is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0Yet I still branded myself as a flautist. As a result, I had been asked to play with a praise band for a church service. It was a request to which I had said a breezy, “Sure!” feigning confidence that I could play this instrument that hadn’t seen the light of day for months.

Inside, though, I wavered. Because I hadn’t practiced, I knew my chops – those mouth muscles you need for good tone – were out of shape. My fingers were not as limber on the keys as they were in my college days. Now, I would somehow have to put all of those skills together again in attempt to make something beautiful: build up my chops, get the notes under my fingers, and put it all together to make the music sing.

The practice was rough at first. My mouth and face muscles were tired after ten minutes of playing. My scales were rocky. I found myself having to clap out the beats of the notes on the page, rhythms that five or six years ago I would have breezed through on a first read.

I wanted the results of this practice to come quickly. What would it take to get back to feeling like the strong and confident musician I had been in college?

I started to practice again, every day. At first, my mouth muscles tired after 15 minutes – a far cry from what I had been capable of in college. But the more time I spent with my instrument, the easier the songs became, and the longer I found I could play without getting physically worn out.

Photo by hermaion on Pexels.com

Photo by hermaion on Pexels.comWriting is like that. It is a journey of practice, of perseverance, of showing up day after day after day. I know what it feels like to soar, to pump out words and solid sentences and bring stories to life on the page. I also know what it feels like to flounder, to struggle over each word and sentence and wonder if I should just throw in the towel. Good writing, like good music, requires practice. It requires regularity, a rhythm of showing up. If you’ve been out of practice for a while, or if you’re just starting, the first few times you show up can be daunting. Your creative brain will take its sweet time to come to life. Finding the right words will feel like grasping at straws. A nagging downer of a voice will try to convince you that you’re wasting your time, that you are not cut out for this work of creativity, that you’re naïve for believing you are. You’ll tire quickly, and you’ll likely wonder if you have what it takes to keep going.

“Writing” by jjpacres is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Writing” by jjpacres is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0If you want to grow as a writer, practice is not simply a suggestion. It’s a necessity. You’ll encounter a lot of terrible stabs at finding the right words, the best way to say what you are trying to say, in the process. As you stumble around the words, the language, you will find your way. As Sarah Cy puts it, “All writers have to go through bad writing in order to get to the good stuff.”

The writer William Zinsser praised E.B. White for his seemingly effortless prose. But, Zinsser was quick to point out, nothing about White’s writing was effortless.

In fact, Zinsser says in his book, On Writing Well, the opposite is true: “the effortless style is achieved by strenuous effort and constant refining. The nails of grammar and syntax are in place and the English is as good as the writer can make it.”

Nothing about White’s writing is accidental. When it comes to writing, E.B. White is a hero of discipline.

I would argue that when it comes to writing, showing up is more than half the battle. If you show up and you keep showing up, if you keep putting your butt in a chair and plinking out words, sentences, paragraphs, eventually your words will start to sing.

Make no mistake: Writing is hard work. Working at it means we will almost certainly write sentences that suck, pursue ideas that go nowhere and struggle and grasp for the right words. But this is practice in action: the act of trying, then trying again, then trying again.

“Practice means to perform, over and over again in the face of all obstacles, some act of vision, of faith, of desire,” said dancer Martha Graham.

When I show up regularly to my practice of writing, new worlds open up. Ideas beget ideas, and as I try to keep up, the more words I churn out and the better those words work together. Like music practice, the more I write, the easier the writing becomes.

*What does your writing practice look like these days?

July 1, 2021

The (Not So) Complicated Element of Surprise

NOTE: I met Annia Napier, a young writer in Rapid City, around Christmas of 2020. Her great aunt reached out to me with a special request for the holidays. Could she purchase a gift card for her niece, Annia, to spend some one-on-one time with a published writer? Annia, then 15, had completed the draft of one novel and was cranking away on the second. But apart from her supportive family, she didn’t have anyone with whom she could really talk writing and explore the often evasive mysteries of the creative process.

Annia’s aunt surely didn’t realize it at the time, but her phone call was the beginning of a remarkable relationship, one where this 37-year-old writer might be learning just as much from her now 16-year-old understudy as that 16-year-old is learning from her. In Annia, I see myself as a teenager. I recognize the determination and uncertainty, the dogged desire to succeed and the importance of receiving persistent encouragement from the adults in her midst.

Were it not for the few adults who believed in me and my passion as a teenager – Jasper Warembourg, my high school English teacher; Janet Montgomery, the editor of my local newspaper (and Jasper’s wife); and my parents – I never would have pursued writing as a career. It would have been too easy to throw in the towel, convince myself that I wasn’t good enough to succeed, tell myself that no one cared about what I wrote, anyway.

Annia’s creative energy, curiosities about life and incredible self-motivation are refreshing and inspirational. As we work through her first novel together – tightening the plot, strengthening the characters, exploring why various elements of story matter – Annia is coming to bat for me. She has graciously agreed to help me in the coming months with social media posts and will contribute to my blog once a month.

Here is her first post.

I invite you to follow the creative journey with us. And when Annia’s debut novel is ready for publication, we’ll let you know!

-Kate Meadows

When I first started writing, I assumed that if your writing were complex, naturally it would turn out good. I never really understood what people wanted in their reading experience, and I never understood what I truly wanted to accomplish in my own writing. As a young writer, I am still figuring that out. All I knew was that I had an idea, and I wanted to bring it to life. To do that, I reasoned, it had better be complex. As I have learned more about writing, I have realized writing and storytelling, whether in books or films, are quite complex. But they are not complex in the way I once thought they were. The complexity comes in the ways one’s ideas connect to create a whole picture. For a whole picture to exist, the writer or storyteller must first have the ideas and recognize what makes those ideas unique. If the creator is able to connect the ideas well, it is as if you, the reader or viewer, have entered into a mystical realm. Sometimes, the ideas I have about what I am going to write are overwhelmingly complicated, and I have to make the decision to go with the flow. If I resist the flow, sometimes my mind cannot handle the chaos of it all. Other times, my ideas can be pretty simple, and I have to come up with more ideas to make the story work, which can be hard, too.

Annia Napier

Annia NapierOften, I am not sure what I am doing when I’m planning my work. But I know that if I stay open to the possibility of surprise, amazing things can happen when I walk into the unknown adventure of storytelling. You know when you have ideas, but there are all these blank spaces in between? You have the simple parts that are easy to understand, but you do not yet know how you will connect those parts. As much as I want to push forward with my work at this stage, I find that, more often than not, I have to be patient. I have to wait for that “aha” moment to arrive. That epiphany of how to connect the dots comes in its own time and in its own way. If I force it, my story no longer feels genuine. I have learned to trust the process and expect to be surprised. Because, when that “aha’ finally does come, I am left joyfully astonished. The creative muse puts a fire into my work that I never could have, had I not simply trusted the creative process. It reminds me of why I want to write and tell a story. Every part of writing is an adventure. There is adventure in the waiting, and in the writing process itself. There is adventure in the parts of the process you enjoy the most, and adventure in the most difficult and frustrating parts.

I love it when an idea clicks in your mind after hearing a smart quote or learning something fascinating from research. I also love that “click” of an idea when you realize the truth about something. You want to share that truth with others, and sometimes, it can be the truth your character needs to learn in a story, as well. Although you both, the author and the character, never knew it, that simple occurrence or exchange in your life can be the thing that connects the dots. But these moments can only happen if you remain open to possibility and believe that answers throughout your creative process can present themselves in unexpected ways.

I have found it is satisfying when a complex thing gets simplified by the timely knowledge and experience that you gain over time. Sometimes things become simpler as you learn and grow, and other times they become more complicated. But that is just how it works, because life, as we all know, is simply complicated.

June 7, 2021

Why Do We Tell Stories?

Why do we tell stories?

As a writer, I am constantly thinking about this. Stories are everywhere. They are in the office chit-chat on a random Wednesday morning. They are flurries of words between energetic kids, recounting a wild soccer match or telling about a sister’s sleepover. Storytelling is practically an art form in small towns – down at the local café over one-dollar coffee, at the post office during a quick morning errand, at the corner bar with Garth Brooks wailing in the background, in the milk section at the grocery store.

Sharing stories is a pastime. It is an innate desire within us.

I would even go so far as to say that telling stories is a need.

But why?

If we think about it hard enough, most of us have been sharing stories since we could talk. Stories are communication, and communication is a form of connection.

In 2020, I took on the role of editor for a slick magazine that covers Sublette County, Wyoming, where I grew up.

I had tons of story ideas. I scoured back issues like a thirsty dog, taking in the people, the places, and the stories behind them.

I am passionate about the place where I grew up, and I can think of no cooler mission than to share stories about that place with people in my circle.

But just because I love these stories doesn’t mean that others magically will.

Writers often fall into this trap – the trap of not thinking outside of themselves when it comes to the stories they share. We get so excited about our own creativity and our own ideas that we fail to consider the world outside of those ideas. We forget or don’t think to ask:

Who else might be interested in this? andWhy should anyone else care about this?In my own excitement over telling stories about my home county, I started to wonder: Why do I love stories about this particular place so much?

The answer wasn’t hard. Each story I read in Sublette County Magazine whet my appetite for my home stomping grounds a little more. The more I read, the more I realized how much I missed this place where I was blessed enough to grow up – the grey-blue mountains that stretch like mighty trophies across the horizon, the silvery sage brush and deep green pine, the rough-and-tumble life of eeking out a living in a place where only the most hearty plants grow and only the most hearty souls flourish.

Ever since I had landed my first real “writing” job as a reporter for my local newspaper, The Pinedale Roundup, as a teenager, the stories from my home county had been my favorite stories to tell. In the years since I left Sublette County – first for college, then for marriage, a career and a family – I have lived in multiple states and communities of all sizes. But I don’t know any of them quite like I know my home county. No matter where I was, I seemed to still gravitate to those stories from my childhood and the people and places that helped shape me.

But to make these stories matter to people besides me, I have to give potential readers a reason to care beyond my own nostalgia. Nostalgia is warm and lovely, but it’s personal. Just because I have sweet memories of so-and-so or such-and-such place doesn’t mean that anyone else will.

One of the best nuggets of writing wisdom I’ve heard is this: A first draft is telling a story to yourself. Revision is telling a story to everyone else.

Often, the first step to sharing a meaningful story is to get it down for yourself. This lays the groundwork for expanding your story to a broader audience.

I love what ghost writer Alex Abramovich says in a podcast interview with Mike Rowe, the Dirty Jobs guy. Abramovich says: “One thing I’m pretty sure I know about writing is that if you have the capacity to surprise yourself while you’re doing it, you might be able to surprise and delight the reader.”

Still, the question doesn’t go away: Why do we tell stories?

I think the question is so persistent for me because there is no easy answer. There is no one answer.

We tell stories to remember.

We tell stories to compare.

We tell stories to teach and to learn.

We tell stories to entertain and to be entertained.

We tell stories to connect.

At its heart, storytelling is communication. And communication, I believe, is the first step to connection.

Why do you tell stories? What stories do you want to hear? What stories need to be shared? Let’s connect!

January 17, 2021

Find Your Writing Tribe

document.getElementById("thinkific-product-embed") || document.write('<script id="thinkific-product-embed" type="text/javascript" src="https://assets.thinkific.com/js/embed...Find Your Writing Tribe replay & bonuses

November 10, 2020

9 Fun Facts about National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo)

Somerset Maugham supposedly gave this answer to the question of whether he writes on a schedule or only when he is struck by inspiration:

“I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

November is here, and for many writers, that means the enticing challenge of National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo. NaNoWriMo markets itself as a “wildly ambitious writing event,” and it is. To complete the challenge of writing a 50,000-word novel in 30 days, you have to have guts, energy and a strong, enduring supply of motivation. The organizers behind NaNoWriMo make one thing clear: The goal is not to complete a polished novel. It’s to hammer out a first draft.

The difference between a first draft and a final draft is huge. NaNoWriMo is meant to be the flurry of creativity, the skeleton set-up of a long-term project. You take an idea and run with it. You write with abandon. NaNoWriMo will probably not turn you into the next bestselling author (though it does for a very select few). But that was never its intention, anyway. This national movement started 20+ years ago as a simple challenge among 21 writers in the San Francisco Bay area: Start and finish a novel in 30 days. It was the quantity, not the quality, of words that mattered.

“I have a history of dragging friends into questionable endeavors,” founder Chris Baty told David Henry Sterry for the Huffington Post.

Plenty of naysayers caution writers against embarking on this month-long challenge each year. Lack of focus on strong writing is one reason. Some agents and editors have come to dread NaNoWriMo submissions, because the work they receive is unpolished and therefore wastes their time.

But if you want to buck the excuses, chisel out a writing routine and cement a discipline of writing into your daily grind once and for all, NaNoWriMo could be your best friend.

To me, NaNoWriMo is not about a finished product; it’s about implementing a sustainable writing routine and showing up for that routine every day.

Here are 9 fun facts about National Novel Writing Month:

To complete a 50,000-word work-in-progress within 30 days, you should plan to write an average of 1,667 words per day.Since its founding in 1999, NaNoWriMo has become a nationally recognized nonprofit that supports writing fluency and education.-More than 900 volunteers across the world coordinate writing sessions in libraries, coffee shops and elsewhere.You set your own writing schedule. When you sign up (it’s free), you can download the complete NaNo Prep 101 Handbook. The handbook includes lessons for how to develop a story idea, how to create complex characters, how to organize your life for writing, finding and managing time to write and more. You can even take the “What’s the best writing schedule for you?” quiz.If you’re participating, you’re a “Wrimo.”Sara Gruen’s Water for Elephants, a New York Times bestseller in 2006 and 2007, started as a NaNoWriMo project.In its first year, 1999, NaNoWriMo had 21 participants. Twenty years later, participants number over 300,000.In 2004, NaNoWriMo launched a young writers program. This program encourages kids from Kindergarten through 12th grade to write a pre-determined number of words in 30 days, as set by their teachers. The program includes lesson plans, writing ideas and resources. During its first year, 4,000 students in 150 classrooms participated. By 2017, more than 100,000 students in 9,000+ classrooms took on the challenge.You “win” if you finish. That means you upload your entire work-in-progress to Nano’s word counter platform in the final days of November. If the word counter detects 50,000 words or more, you are declared a winner. Here’s a look at the finishers over the past two decades:

1999: 21 participants, 6 winners

2000: 140 participants, 29 winners

2001: 5,000 participants, 700 winners

2002: 13,500 participants, 2100 winners

2010: 200,500 participants, 37,500 winners

2015: 431,626 participants, 40,000+ winners

2018: 287,327 participants, 35,387 winners

Today, NaNoWriMo boasts 798,162 “active novelists” and 367,913 novels completed.

Sources: https://www.wikiwrimo.org/wiki/NaNoWriMo_statistics, https://blog.nanowrimo.org/post/181053064731/nanowrimo-2018-by-the-numbers

One of the keystones to NaNoWriMo’s success is its focus on community.

“… somehow lowering our expectations and transforming novel-writing into a group activity — most of us got together after work to write — ended up doing good things to our brains and books,” Baty told the Huffington Post. “If you want to get more writing done, try working in the same room with other writers.”

This year, NaNoWriMo launched a new hashtag, #StayHomeWriMo, with writing prompts geared toward physical and mental wellbeing. One silver lining in the COVID-19 pandemic: National Novel Writing Month is a perfect activity for those who shelter in place.

Have you ever attempted this wildly ambitious November quest? Have you always wanted to, but hesitated on that edge of driven-by-creativity-but-not-brave-enough? I would love to hear from you!

October 1, 2020

The Case for Community Newspapers

What is the value of local news to you?

How do you stay informed about what’s happening in the world? How do you stay informed about what’s going on in your community? Where do you get your news these days?

These are critical questions I’m passionate about pursuing, because, as we all know, the state of news in our country is changing dramatically. Strong labels come with just about every national news source – CNN, FOX, NBC, MSNBC. And when was the last time you heard someone praise their local newspaper?

News on the national front is more polarized than ever. News on the local front is disappearing. That, to me, is scary.

In a 2019 article, the Wall Street Journal reported that nearly 1,800 newspapers closed between 2004 and 2018. Collectively, the closures left 200 counties without newspapers.

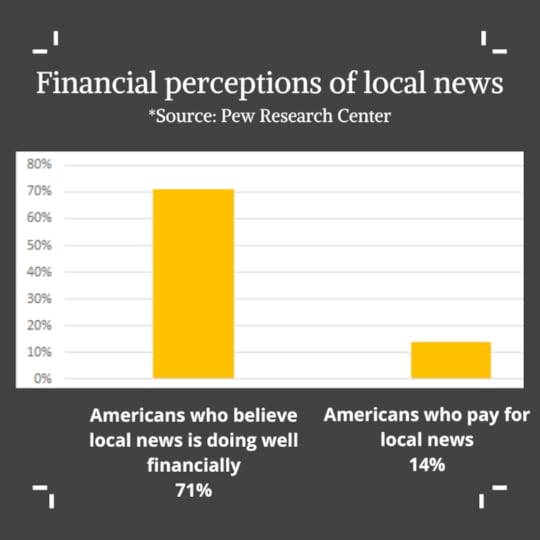

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that newspaper jobs declined by 60 percent between 1990 and 2016. Newsroom employees – the people who actually report the news – declined by 45 percent between 2008 and 2017, a Pew study found. Yet another Pew study found that 71% of Americans believed local news outlets were doing well financially, though only 14% actually paid for local news.

These stark numbers beg the question: What value does our society place on local news?

When a literary magazine I love announced it was seeking essays on hometown newspapers for a new anthology entitled INK, I shoved everything on my to-do list aside and started writing. The topic, to me, was too important to ignore. My relationship with community journalism started when I was a freshman in high school, because the editor of my hometown newspaper – The Pinedale Roundup – gave me a chance.

The Pinedale Roundup is a 115-year-old community icon for Pinedale, WY, and Sublette County, once the least populated county in the state. When John F. Patterson was doggedly trying to establish a town on the banks of Pine Creek in southwest Wyoming’s high and rugged terrain, he envisioned a newspaper as a critical component to defining a town. A newspaper could connect people who were trying to make a go at life in this hardscrabble place. It could also showcase the land and its opportunities for citizens and newcomers to make it their home.

A glance through the early issues is a wild ride of entertainment. As I report in my forthcoming essay for INK:

The news was divided by area: Merna (“Supt. Anderson of the Forest Reserves has been seen in these parts lately”); Big Piney (”All are pleased with the abundant hay crop this year”); Valley Roundup (”P.V. Sommers passed thru [sic] Pinedale recently en route to Pacific Spring, where he expects to recover some of the horses stolen from his camp near the Black Butte during July … Mr. Fred S. Boyce, who has been on the sick list for some time the past summer is again on duty, rather thin and pale but still in the ring”). In the Cora section, Brandon (the Roundup’s first editor) mused: “A friend of mine asked me the other day the name of the joint on the left hindleg of a cat, the joint the cat usually sits on. I was unable to reply. Will some kind reader inform the editor so I may know in the future.”

The news wasn’t earth-shattering. It wasn’t sensational. It was simple, unfussy and conversational. But it served a definite purpose: to connect people with one another, and to connect people with the place they called home.

Since then, the flavor of community news has evolved dramatically, not only in focus of what constitutes news, but also the way people consume news. The digital landscape, accented by noisy social media platforms, has hugely influenced the way people get their news. It has also upended advertisers’ approaches to reach consumers. Advertisers want to be where their consumers are. If their consumers’ eyes are not on the local newspaper, big advertising dollars won’t be, either.

These colossal changes, as most of us know, have also wildly affected newsrooms across the country. One example of many is the Omaha World-Herald, which has let go of one-third of its newspaper staff within the past two years. MarketWatch columnist Brett Arends writes:

Gutting papers and laying off reporters is a lot easier these days. Not just because of the economy, but also because of a very successful 50-year cultural campaign against “the media,” who are portrayed as evil “elitists” (and the enemy, of course, of the American people).

As the local news landscape shrinks, Americans are provided with less and less information about what’s happening close to them, reports the Wall Street Journal. Local newspapers are vanishing in part because they struggle to find sustainable ways to deliver quality news to their readerships while still making enough money to pay their staff and cover overhead costs. Turnover is as common as cracks in a sidewalk. The reporters who fill the vacancies often have no personal connection to the people or places on which they are reporting. They are willing to work for wages that hardly rival an entry-level position. Readers’ faith in the stories declines, because the stories lack quality, depth, solid reporting. The greater public loses trust in the fickle voice of its community.

So what happens to a community when its newspaper loses credibility, respect, community backing? Where is the pulse of a town if not in stories that are communicated thoroughly to the wider public?

As I worked on my essay about my own 115-year-old hometown newspaper (which, by the way, still comes out weekly but at half the size as it was in its heyday and with enough punctuation and grammatical errors to make Strunk and White turn green), a looming question nagged at me:

What is news?

A second question piggybacked it:

What is the purpose of a newspaper?

Is the answer different today than it was back in 1904, or 1940?

One purpose of a newspaper is to ask – then answer – questions. A good reporter is not afraid to ask questions. She starts with the questions everyone is asking. But then, she goes deeper. She asks more questions, and she picks up answers like breadcrumbs, following a trail to the story beneath the surface.

In an interview with Lapham’s Quarterly Review, former editor-in-chief of The Guardian, Alan Rusbridger, acknowledged that advertising and news are floating apart. “If that’s true, and if society still needs anchor news and people who can say, ‘That’s true,’ ‘That’s not true,’ then we have to think about news as a public service like an ambulance service or a police service. And how we answer is question we ought to start discussing.”

Indeed, Arthur Miller, the American playwright and essayist of Death of a Salesman and The Crucible fame, defined a newspaper this way: “A good newspaper, I suppose, is a nation talking to itself.”

Drill that down to the local level, and you get something like this: “A good newspaper, I suppose, is a community talking to itself.”

But what are conversations – good, thorough, responsibly researched conversations – worth to you, reader?

What conversations is your community engaged in? What are you, as a local citizen, curious about? As a member of a specific community, what do you need to know?

The broader question remains for all of us, writes Brett Arends: If local reporters don’t cover the local courts, and City Hall, and zoning board meetings, and the goings-on of the local chamber of commerce, who will?

It’s time we start thinking about local news as a civic need. Places and people will continue to change, and history will continue its slow and steady march, regardless of whether people write about it. But stories are the lifeblood of any community. Without stories, we die.

The future of local news is hanging in the balance. A future without newspapers, says Nicco Mele of the Shorenstein Center, is “actually a crisis for democracy.”

How does a community talk to itself? What is the value of one community’s heartbeat?

Let’s start talking.

September 6, 2020

4 Ways with Zucchini

“Zucchini” by leguico is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Zucchini” by leguico is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0In August, zucchini starts to show up in western South Dakota by the bunches. Farmers bring their stash to town in white plastic grocery bags. Neighbors pick their crop and go door-to-door in a friendly (and sometimes desperate) act of sharing.

“Do you know anyone who keeps their car doors unlocked?” one weathered farmer asked me in jest with a grin a few weeks ago.

I didn’t catch on at first.

“What do you mean?” I asked him.

“I need somewhere to put all of these zucchini and squash!” he said.

I love this time of year for the zucchini, but on another hand, I dread it. That’s because my family finds this pulpy green vegetable disgusting. I am snagged between accepting our friends’ and neighbors’ acts of goodwill to share and my family’s groans and eye rolls whenever I bring one (or more) of the green buggers home. My family detests zucchini so much that on a recent road trip to Wyoming, they invented an A-B-C game in which they rolled through each letter of the alphabet, taking turns coming up with adjectives to describe the green monster. “Awful!” one would say. “Blech!” another would say. I was the only one of our family of four to counteract the bad with the good. I came up with nice words like “Delicious” and “Outstanding.”

“Went to the treasure tree tonight and scored this Eric Carle’s ABC Game!”

“Went to the treasure tree tonight and scored this Eric Carle’s ABC Game!” by Heathere Willoughby, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Much as my family dislikes it, zucchini is fun. It is totally good at being sneaky. It wears the imposter hat with ease. Grate it and stir it into a quickbread mix for an extra-moist breakfast delectable, and no one will be the wiser. “This banana bread is so good!” they’ll say, and they’ll ask for more.

A friend of mine, not knowing my husband hated zucchini, once convinced him to try her No Apple Apple Pie. He never would have tried it had he known what it was called or what was in it. In the moment, he was being polite.

“You love pie, don’t you?” my friend asked.

“I do,” my husband replied.

“Then try this!” she said. “You’ll love it.

He did, and it wasn’t half-bad.

That is, until he learned it was called No Apple Apple pie and the substitute for apple was zucchini.

One of the reasons why my husband hates zucchini is not because of the taste (though that is another reason) but because it is an imposter. “If you want to make an apple pie,” he’ll say, “just make an apple pie!”

My husband believes that zucchini, like its squash cousin, is a food that requires flavoring for it to taste like anything. In other words, it is a food that can’t stand on its own.

“If you add brown sugar, it tastes like brown sugar,” he’ll say. “If you add garlic and parmesan, it tastes like garlic and parmesan.”

I have encountered very few foods that are as controversial as zucchini. It’s one of those foods you either love or hate; there seems to be no middle ground.

So, what do you do in the height of zucchini season when three-quarters of your family hates the stuff and kind friends and neighbors so kindly want to share their abundance?

You accept their goodwill offerings with a smile, say thank-you, and get to cooking. Your family will roll their eyes at you. They’ll look in the fridge and say, “What is THAT?!” But if you’re sneaky, you can feed them the most delicious muffins that will have them coming back to the breakfast bar again and again.

Here are 4 ways to cook with zucchini:

1. Zucchini muffins (from Williams-Sonoma)

1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

3/4 cup sugar

2 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 tsp ground cinnamon

2 eggs

1/3 cup canola oil or almond oil

1/4 cup orange marmalade

1 tsp vanilla extract

1 zucchini, 4 oz. total, shredded and drained on paper towels

3/4 cup dark raisins or dried sweet cherries

1/4 cup pecans or almonds, chopped

Preheat oven to 400 degrees. Grease 10 standard muffin cups with butter or butter-flavored nonstick cooking spray. In a bowl, stir flour, sugar, baking powder, baking soda, salt and cinnamon together.

In a separate bowl, whisk eggs together with oil, marmalade, vanilla and zucchini until well mixed. Add the flour mixture in three additions and beat until just evenly smooth and moistened. Stir in raisins and nuts. Batter will be stiff.

Spoon the batter into muffin cups, filling no more than three-fourths each. Bake 17-20 minutes, until the muffins are golden and springy to the touch, and a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean. Transfer pan to a wire rack and cool for 5 minutes.

2. Zucchini Sugar Cream Pie

Zucchini – peel enough to make 1 1/2 cups.

Cook 5 mins in microwave

Combine in blender:

Zucchini

1 cup sugar

3 TBSP flour

1/2 TBSP melted butter

1 cup evaporated milk

1 tsp vanilla

1 egg

Pour into an unbaked pie shell; top with cinnamon.

Bake at 425 degrees for 15 minutes. Lower oven temp to 350 degrees and bake for 10 more minutes or until done. (It will set a little after its out of the oven.) This also freezes well.

3. Zucchini apple salad (from allrecipes.com)

1 pound zucchini, diced

3 eaches apples, diced

½ green bell pepper, diced

½ red onion, chopped

⅓ cup vegetable oil

2 tablespoons red wine vinegar

1 teaspoon white sugar

1 teaspoon dried basil

¾ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon ground black pepper

Combine zucchini, apples, green bell pepper, and onion in a bowl. Whisk vegetable oil, vinegar, sugar, basil, salt, and black pepper together in a separate bowl; drizzle over zucchini-apple mixture. Toss to coat.

4. Zucchini Chicken Casserole (adapted from family friend Debbie Sudbury)

6 cups sliced zucchini

4 chicken breasts, cut into bite-sized pieces

1-2 TBSPs olive oil

1 pkg Stove Top stuffing mix, chicken flavor

1 medium onion

1 cup sour cream

1 can cream of chicken soup

Boil zucchini in small amount of water until tender; drain. Sautee chicken (I season mine with an all purpose seasoning, like Cavender’s All Purpose Greek Seasoning) in olive oil until no longer pink; set aside. Mix soup, sour cream, onion in a medium-sized bowl.

Grease a 9×13 pan. Place 1/2 of stuffing mix on the bottom of the pan. Add a layer of zucchini. Add soup mixture on top of zucchini, then chicken on top of soup mixture. End with stuffing mix on top.

Bake at 350 degrees for 1/2 hour.

What are your favorite ways to use zucchini? I’d love to know, even if I’m only cooking for myself!

July 15, 2020

Copyediting. Line editing. Developmental editing. What’s the difference?!

Copyediting. Line editing. Developmental editing. What’s the difference?!

“Editing” is a pretty all-inclusive term. Many people use it interchangeably with “proofreading,” thinking the goal is the same. You want clean written content, right? Isn’t that what matters?

Well, yes. But clean content is not always the only thing that matters. Editing can be an all-encompassing process, depending on the writer’s end goal. If it’s simply clean copy you’re after, then a thorough proofread might be all you need. But what if you want to make sure your ideas flow, your language is hard-hitting, your message or story is as clear as it can be?

That’s where some more in-depth editing can be your friend. In the writing and editing industry, wordsmiths commonly throw around terms such as “copyediting,” “line editing” and “developmental editing.” But when you’re a business owner or a creative writer who just needs help making your words flow, does it really matter what type of edit you request? What’s the difference between them, anyway?

Read on to learn about the three most common types of editing and what sets them apart:

Developmental editing (also known as comprehensive editing)

Developmental editing takes into account the big picture of your written content and considers how all of the smaller details that comprise that big picture work together. I commonly use the “forest-through-the trees” cliché to explain developmental editing to my clients. If your written content is the forest, we aim to better understand the forest by examining all of the trees that collectively create it. We focus on organization, flow, momentum and pacing. In creative work we consider plot and character development. We work on voice, story or brand consistency and style. Line editing and proofreading are included in a developmental edit. We aim to better understand the big picture by thoroughly examining all of its pieces – one at a time and then as parts that work together.

Line editing

Line editing considers the big picture of how you communicate a story to a reader. Where attention in developmental editing is on the big picture and the many facets that comprise the big picture, line editing more heavily focuses on the big picture and the writer’s general style. Do you focus on fresh details, or do you use clichés? Do you drill down into specifics, or is your writing more broad? A good line edit will point out over-used words and phrases, lacks in consistency and confusing passages or transitions. A thorough line editor will suggest how and where the writing can be tighter, simpler and more concise.

Copyediting

Copyediting is a lesser known cousin of developmental and line editing that drills down into the more technical aspects of putting words together. Copyediting takes into account grammar, punctuation and spelling, and pays particular attention to consistency across content, often adhering to a specific style guide, such as AP, Chicago, MLA or Turabian. This type of editing ensures that content is properly formatted (for example, all bullet points are visible and properly indented, captions match images, no sentence is missing a period, etc.) and clean.

A copy edit will also point out any factual or descriptive inconsistencies. For example, let’s say you are describing a school classroom with an east-facing window. Then, further along in the piece, a character marvels at the blazing sunset as she stares out that window. A good copy editor will catch the discrepancy – you can’t view a sunset from a window that faces east. Or, let’s say you are preparing a presentation for your company on the history of a product. One slide says the product launched in 1961. Another slide says that the developers celebrated the 50th anniversary of the product launch in 2001. A good copy editor will catch that error: The difference between 1961 and 2001 is 40 years (not 50).

Proofreading

And finally, there is that darling of the editing family called proofreading. Despite what many people think, “proofreading” is not the same as “editing.” Where editing takes a harder, closer look at both the whole and the parts of a piece of writing, proofreading is really where the grammar police show up. Proofreading sticks exclusively to the mechanics of a piece of written content to ensure proper grammar, punctuation and spelling throughout. At its best, proofreading might be considered “editing-lite.” It is often the final step before publication or sharing your writing with others.

So does it matter what type of editing or proofreading service you seek? That depends on your end goal. A professional editor can help you tremendously – and I would submit that every writer, website owner, business owner, anyone with written content they want or hope to share with others – needs one. Your words belong to you. You want them to adequately reflect who you are.

Do you want Grandma to eat dinner with you? (Let’s eat, Grandma!)

Or do you want to eat Grandma? (Let’s eat Grandma!)

March 31, 2020

The Time is (Write) Now

As our country stands #alonetogether, how are you tapping into or stocking your creative well? Do you find that you have extra time on your hands now, as you grow used to this temporary lifestyle of social distancing? Are you gaining new insights about yourself, your relationships, public (or private) education, our nation or the world in general? How are you coping in this national and global emergency?

I am observing – and trying to record – new phenomenons every day as we #stayathome. More people are walking past my living room window. My kids are learning how to use a jump rope, and last week I taught them how to do a proper sit up. The owner of a construction firm shifted from building modular spaces such as hotel rooms and college dorms to mobile temporary emergency isolation hospital rooms, almost overnight. A small care package mysteriously showed up on my friend’s doorstep after a particularly tough day at home with her kids. Art and color is blooming everywhere with #chalkyourwalk.

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons and https://www.flickr.com/photos/1078773...

Photo courtesy of Creative Commons and https://www.flickr.com/photos/1078773...What is your story in the COVID-19 crisis? We are, all of

us, part of a historical moment on this planet. The time is now. Whether you’re

grieving or suffering, optimistic or fearful, faith-filled or panicked, I

encourage you to write through this time. Write about what’s going on around

you. Write about your part or your role in this emergency that touches all of

us. Dust off that story that’s been hibernating in your desk drawer, the one

you would come back to “someday.” The time is now. Explore the seed of an idea

that has never had the time to grow. Record your memories or help someone else

record theirs. Use this time. The time is now.

Jeff Goins writes that a crisis is an opportunity to create

something new. “Because the world is changing, and it will need your

contribution. In a week or a month or a year from now, how will you look back

on this time?” he asks. “Will you have used your opportunity to contribute

something to this new world? Or will you have only enjoyed an abundance of hand

sanitizer?”

Your contribution doesn’t have to be mind-blowing. It doesn’t

have to be New-York-Times-bestseller-worthy. How might your experience or your

creative spirit educate or inspire your children, your grandchildren, their

children?

During the month of April, I am offering a 10% discount on all editing and manuscript critique services with Kate Meadows Writing & Editing. I offer a free 30-minute consult to all new clients. Earlier this month, I launched a “30 Ways 30 Days” campaign, where I share on social media platforms one way each day to love your neighbor. Today’s way to #loveyourneighbor is this: Help someone record their life memories. If you’re interested in doing this, email me (kate@katemeadows.com) and I’ll send you 50 questions to consider when recording a life story.

If I can help you in any other way as a writer or editor

during this time, please don’t hesitate to reach out. We are #alonetogether,

but none of us should be alone. Writing, at its base, is communication. Let’s

keep the conversation going.

March 20, 2020

30 Ways to Love your Neighbor, even through Social Distancing

Many of us have heard some form of this truth over the past week: There is a fine line between panic and preparedness.

Isn’t it ironic that, while seemingly no one can escape some

form of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, while we’re all in this together, the

most important thing we can do right now is separate ourselves from one

another? We’re all in this together, yet we hunker down, apart.

Even as mystery and fear surround this sickness, even as the

CDC urges no gatherings of 10 or more, I urge you, strangers and friends, to

focus outward, not inward. Choose faith over fear. Count your blessings. Pray

boldly, and pray without ceasing. And, during this unprecedented time of need,

love your neighbor.

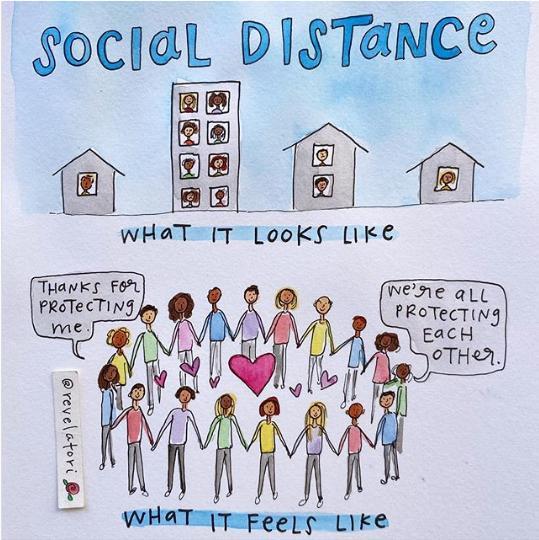

Copyright Tori Press @revelatori (Instagram)

Copyright Tori Press @revelatori (Instagram)It is so tempting to want to hole up during this time of

wild uncertainty. It is tempting to want to control every corner of your life

that you can: stock your pantry, cash in on investments, hoard enough toilet

paper to last your family until Christmas.

There is a fine line between preparedness and panic.

Before the coronavirus made its way to American shores, we were a nation wrestling with an epidemic of loneliness. How easy it is to lose touch with each other, to fear strangers, to stay protected by keeping to yourself. Now, our whole country is under a heavy expectation of social distancing, encouraging us to pull into ourselves even more and limit our exposure to the outside world.

In this time of crisis, even as we navigate life apart from

each other, let us not forget our neighbors.

Do not let fear convince you to stick your head in the sand.

If all we do during this time of social isolation is focus on ourselves, our

whole world will go grey. It will lose its color, its energy, its life.

Inward focus breeds panic.

Outward focus breeds compassion.

Inward focus breeds fear.

Outward focus breeds faith.

Hoarding is an act of selfishness. Helping is the opposite.

Just because we remain physically distant from one another does

not mean we cannot still acknowledge and love our neighbors. In fact, there has

never been a better opportunity to serve our neighbors. From the shelter of our

homes, there has never been a more important time to look outward, to see the

world beyond ourselves.

Who are your neighbors? The people who God puts in your

path. Your mail carrier. The school janitor. The widower in his 70s who lives

on the street corner. A college student you know who is suddenly moving back

home. The teenager on your street who desperately wants to escape to …

somewhere.

How can you love your neighbor? Let us count the ways. Over the next 30 days, I’ll post on Facebook and on Twitter (@Meadowswriter) 30 ways to love your neighbor through the COVID-19 pandemic. I’ll post one new suggestion every day, using hashtag #loveyourneighbor.

Have you encountered or do you have an awesome idea for how

to serve your neighbor in this crisis? Please share it, and I’ll be sure to

pass it along.

Are you someone who lacks food or specific resources at this

time? Please have the courage to reach out and ask for help. So many people have

servant hearts and long to help people in need – no questions asked.

How could a willing neighbor specifically help you or someone you know, right now? Tell me on Facebook, on Twitter or via email at kate@katemeadows.com.

Numerous news articles have pointed out how the closures,

cancellations and social distancing sweeping our nation is exposing gaps in the

inequities of our society. Children with access to internet and computers at

home will continue to learn, but what about children with no internet or

computer access at home? Children with stable parents will be cared for at

home, but what about children in unstable households? Families with extended

family nearby have each other to lean on, but what about families with no one

close by?

Above all, through this time of isolation, let’s keep the

conversation going. Although we are physically separated, let us seek ways to

stay connected and serve each other in love.

None of us can save the world. None of us will be world heroes.

But, through courageous, outward-focused service, all of us can be heroes of

the corner of the world we’re in. Imagine if we all moved forward looking out

while staying in.