James Ferron Anderson's Blog, page 3

October 30, 2014

Journey Without Maps

I’ve been reading some of the comments on Amazon and Goodreads on Graham Greene’s book before writing this. I’ve read most of Greene’s work, some many times, but not this until just now, and I was interested in what others thought of it. I don’t seem to see it the same way. You can investigate those other opinions for yourself, but here’s a little of my take.

It goes back to Norman Sherry’s fabled three volume biography. In the introduction to Volume Two he writes: ‘In life he was not willing to allow full entrance even to those familiar with his secret life. ‘ (Two ‘life’s’ there: tut tut Sherry) He goes on to state at greater length what is generally accepted as true about Greene’s character: that he put lots of time and energy into concealing himself from all those around him, that he kept secrets privately and professionally, that for example he kept two diaries, that you could hardly ever believe his stated motivation for anything. Sherry follows this description of Greene’s deceptive nature by trotting out that old canard again about him playing Russian roulette six times in five months. His source for this? Greene told him.

There is a great element of this in Journey Without Maps. I suppose that is my main thought about it: that it is a demonstration of both Greene’s wonderful ability with language, and of the untrustworthy nature of his texts. For one thing it was not without maps, and not the map he described as having written across the territory in which he proposed to walk the word ‘Cannibals’.

I don’t know if it’s possible to learn why Greene went outside Europe for the first time and set himself this dirty, dangerous task of walking across Liberia for hundreds of miles, taking his debutante cousin with him, but I do know the narrative consists of some facts mixed with one dodgy bit of information after another. Even the cousin’s age is stated wrongly in newspaper reports of the time, this information presumably given by themselves: she was twenty-eight and not twenty-three.

There is a school of thought on this that Journey Without Maps is a glimpse into a world long gone, and a glimpse into a way of approaching this world, that of the middle-class son of the British Empire venturing abroad in those quieter years before the outbreak of WWII. And of course the other take on it: that it is a journey into the psyche of the participants, or of Greene anyway, for again an untruth, he writes as if he was alone and not accompanied by a cousin who is handling the stresses better than he is.

If it amounts to anything I think it is wonderful writing. We are in some wet, hot , muddy, insect-laden jungle one moment, and back in the Cotswold village were he has left his (unmentioned) wife and months-old child the next, and he makes it all flow and work and resonate and enthral us. Or me anyway. Jesus, could anyone ever write as well?

But I never believe a word he says. What he is telling you might be true. The opposite might be true. Anything might be true. Or not. It’s Graham Greene. To treat this as it is presented, as some travelogue of a walk in Liberia in the mid-thirties, taken on a whim, is to be a Norman Sherry: it’s to know the man telling you all this is a liar (the most wonderfully skilled writing liar conceivable, but a liar) and then swallow what he tells you anyway.

Read it for the skill of the writing. But let’s not be a Norman.

July 18, 2014

Willpower? What willpower?

Willpower, willpower, willpower… give me a break. It doesn’t even exist.

Why do I not believe that willpower exists?

Intuitively, it might feel obvious that we have willpower. What else is causing me to write this when I could be sleeping or cutting a sandwich or reading a book? What will make me go to the gym later? To not drink alcohol this evening? But just because willpower feels like it must exist doesn’t mean it actually does. Just because it feels like the sun must revolve around the earth doesn’t mean that’s how it works. Just because you can’t see microbes doesn’t mean you should stop taking that medicine when you get sick. Pretty much the entire sum of our knowledge is based on things our intuition gets wrong. The existence of willpower comes into that bag.

Some people, I know, find it hard to just say: ‘I don’t know.’ Not me. I say it all the time. It’s because it’s true. But to say: ‘I don’t know’ and not follow up immediately with an attempt to guess… that’s the real biggie. That goes against all human nature. Any theory feels better, as in more comforting, than none at all. There’s the great scary (maybe) void of nothing, and there’s the comfort of telling ourselves well, this might be right, this might be how it works, rapidly transformed into: ‘Well that is definitely how it works.’

Hence the origins of religion in the Bronze Age, the infancy of the human race, when the wisest men and women knew less about the rules of science than any current three-year-old. Willpower is one of these handy, and outdated, placeholder concepts that people have used to explain systems they don’t understand, with the bonus of being considered personably desirable and rather flattering.

Just about every discussion of willpower I’ve come across involves food in its examples, so let’s not become startlingly innovative. I’ll stick with food.

I want to eat that muffin because it will taste delicious.

I don’t want to eat that muffin because it will encourage a weight gain.

Which do I want most? That is the one I will do, as with just about everything else, and this goes for all of us. I ain’t so special. Whatever decision I make I could, strictly speaking, label as a consequence of willpower. BUT… I know the one that will end up labelled as willpower.

If I decide to eat the muffin that will readily be labelled as giving in (not by me).

If I decide to not eat the muffin that will readily be labelled as an example of willpower. I would argue it is no more the result of willpower than making the other choice. It’s just doing what I want to do most, as usual, but congratulating myself about it. For ‘willpower’ is not an impartial term, but value-weighed, a pat-on-the-back label we attach to others and ourselves when we imagine some commendable decision has been arrived at and carried out. The fallacious concept of willpower can play no real part in decision making.

Napoleon… let’s bring Nap into it. He calls on the mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace to have demonstrated to him his explanation and model of the workings of the cosmos. When he’s done Nap asked: ‘But where does God come into this? and Laplace replies, rather famously: ‘I have no need for that hypothesis.’

There’s no need for the hypothesis, and that is all it is, of willpower. Why not be honest? Let’s hear it for doing what we really want to do most anyway, just as we always do.

July 9, 2014

An injury to one…

If you’ve ever seen an X-Men movie then you’ve seen one of the homes of the Dunsmuir family of Vancouver Island. Hatley Castle has the role of Professor Charles Xavier’s ‘school for the gifted’.

Robert Dunsmuir, a shrewd and opportunistic coal proprietor, was certainly gifted at making money. He had arrived from Scotland as a $5 a week miner, and thirty-five years later was the wealthiest and most influential man in British Columbia. He built a colliery operation that surpassed in size and output the combined value of all other British Columbia coal mines. He constructed and operated a fleet of colliers. He invested heavily in real estate, in an iron foundry, a theatre in Victoria, agricultural lands, and a mainland diking scheme. He built a rail link between Nanaimo and Victoria in return for $750,000 and a government grant that amounted to one fifth of Vancouver Island. He had the rights to all minerals, coal and oil under the land, and all the water and forests above it. He built himself a mansion in Nanaimo and a mansion at Craigdarrock. His heir, his son James, built the massive and ostentatious Hatley Castle.

The Dunsmuir notoriety stems from Robert Dunsmuir’s belief that the mines were his to do with as he chose. He paid lower wages than his competitors, and still preferred to employ Oriental workers on half pay. He resisted the demands for safety improvements made by inspectors of mines, and when in 1877 the island colliers threatened to strike over poor wages and poorer safety Dunsmuir responded by locking them out until destitution drove them back to work at one third of their previous rate.

Between 1884 and 1912 373 men died in gas explosions and rock falls in the Dunsmuir mines (Seven Shillings A Year: Charles Lillard).

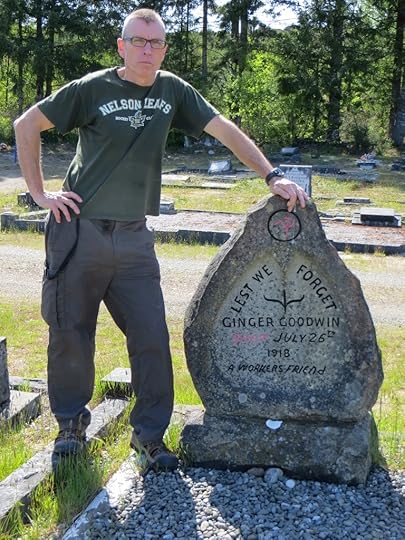

Onto this scene comes Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin. Goodwin was born in Yorkshire in 1887, and emigrated as a miner to Canada in 1906. He worked his way west, and in early 1911 was employed in one of Dunsmuirs’ Cumberland mines. His first record of union involvement dates from this time, during an unsuccessful (as they all generally were) strike. Blackballed after the strike he moved to Trail, where he rose in the ranks of the union.

At the outbreak of WWI he registered as a conscientious objector, stating openly his disdain that the working class were now being employed to kill each other for capitalist masters. Perhaps he had the Dunsmuirs in mind. Goodwin complied with the law and signed up for the draft, but was not conscripted after a medical examination found him unfit for military duty due to lungs damaged in mining.

Goodwin led a strike at the Trail lead and zinc smelter in 1917, bargaining for a standard eight hour working day. Shortly after he was notified that his status had been changed and that he was now fit for duty. As a pacifist Goodwin fled conscription into the Cumberland mountains, fed by fellow workers from Cumberland.

Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin died from a single gunshot on July 26th 1918. The killer was Constable Daniel Campbell, one of three policemen sent to arrest him. The excuse was that Goodwin was about to fire a rifle at the policemen. The shot was to the side or back of Goodwin’s head (reports vary). Constable Campbell was never charged or arrested.

Goodwin had a large funeral on August 2nd, 1918: the procession is remembered to have stretched for a mile. The Vancouver General Strike, Canada’s first General Strike, was held the same day on the mainland, and is a defining moment in Canadian labour history.

The 1980s saw a revival Goodwin’s legacy with the start of Miners’ Memorial Day in Cumberland. In 1989 the mountain where Goodwin was shot was named Mount Ginger Goodwin. A section of Vancouver Island Highway 19 passing through Cumberland was briefly named Ginger Goodwin Way in the 1990s until, on Labour Day 2001, the signs were removed by the newly elected BC Liberal government, an indication of the continuing controversy over Goodwin’s death and legacy.

‘An injury to one…’

July 1, 2014

Aces all round

Sometimes I find a reference to writing that resonates strongly. I go: yes, that’s how I think. That’s the way my mind works. For example the writer of the article likes the book s/he’s reviewing, gives an example from it, and gives an explanation why s/he thinks it’s good. I think the example is good, and think about my explanation of why it’s good. And lo and behold, we have the same explanation.

In this season of Wimbledon William Fiennes wrote in the Guardian last Saturday about John McPhee’s book Levels of the Game. One of the two main protagonists of the book is the African American tennis player Arthur Ashe, winner of the US Open in 1968, the Australian Open in 1970, and Wimbledon in 1975. Here Fiennes gives an example of how John McPhee writes:

‘But the simplicity of his sentences is deceptive. McPhee attends to what he calls “the aural part of writing” – the way it sounds, the tempo and cadence. Look at, or listen to, this beginning:

“Arthur Ashe, his feet apart, his knees slightly bent, lifts a tennis ball into the air. The toss is high and forward. If the ball were allowed to drop, it would, in Ashe’s words, ‘make a parabola and drop to the grass three feet in front of the baseline’. He has practised tossing a tennis ball just so thousands of times. But he is going to hit this one. His feet draw together. His body straightens and tilts forward far beyond the point of balance. He is falling. The force of gravity and a muscular momentum from legs to arm compound as he whips his racquet up and over the ball. He weighs a hundred and fifty-five pounds; he is six feet tall, and right-handed. His build is barely full enough not to be describable as frail, but his coordination is so extraordinary that the ball comes off his racquet at furious speed. With a step forward that stops his fall, he moves to follow.”

It’s not just the way the short sentences create a frame-by-frame slow-motion effect (writes Fiennes). It’s the way the word “lifts” in the first sentence lifts into the paragraph an f sound which then follows its own parabola like a thrown ball through feet, forward, falling, force, fifty-five, full, frail, furious, forward, fall and follow. Subject and medium step out on to the floor like dancers.

It makes sense. I’d buy that. There’s rhythm and more than rhythm. Straightforward word use that rises above its simplicity. Attention to how the words and sentences sound. But Fiennes has said all that needs to be said. No more. Basta. I agree with him.

June 25, 2014

As I Walked Out Into Metaphor

Jeees… metaphor.

Here’s an idea about them that does my head in: that though metaphors can be considered to be ‘in’ language we cannot conceive of language in anything other than metaphoric terms. Or: everything you read and hear is a bloody metaphor in some way. Enough of that. I also largely agree with it.

And so often I see metaphor as taking the reader away from the sensation the writer hopes to depict, from the experience s/he hopes to replicate on screen and paper, and not closer. A different thing is just a different thing, not a better description of the first thing. But it doesn’t have to be.

Here’s an example, not the best perhaps but the most recent I’ve come across, from Laurie Lee’s As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning (1969), found in Saturday’s Guardian:

‘I walked steadily, effortlessly, hour after hour in a kind of swinging, weightless realm. I was at that age which feels neither strain nor friction, when the body burns magic fuels, so that it seems to glide in warm air, about a foot off the ground, smoothly obeying its intuitions. Even exhaustion, when it came, had a voluptuous quality, and sleep was caressive and deep, like oil.

The writing here is ‘voluptuous’ yet precise, and as such it is characteristic of Lee’s style, in which elaborate metaphors serve not as ornaments, but rather as the means of most closely evoking complex experience. Lee does not walk so much as levitate or hover, borne aloft by supernatural stamina, and, in mimicry of this sensation, his clauses, suspended by their commas, also bear the reader along ‘the way’ and onwards into the unknown.’

I agree.

That’s it. I agree. No metaphors.

June 21, 2014

From: The Dangerous Edge of Things

Perry Street, Dungannon, County Tyrone

From: The Dangerous Edge of Things

Our interest’s on the dangerous edge of things.

The honest thief, the tender murderer,

The superstitious atheist.

Robert Browning: Bishop Blougram’s Apology

It was nearly twelve o’clock. Uncle Joe wouldn’t be back the night. No Andy Bap either. All good then. He had his hands in the soapy water of the kitchen sink when the window in front of him shook once, faintly. It would be a bomb somewhere in the town. It didn’t sound large. He had to get up in the morning. He washed another plate and put it on the rack. He wiped down the sink and turned off the light and went up the stairs.

He was walking up and down the landing in the dark brushing his teeth, looking down at his ivory feet on the lino. When he went past the landing window there was a shimmering glow on the glass. The sky outside wasn’t grey and black. It was a vivid wavering red. He went into his bedroom and opened the window and leant out over the street. The red sky had dark clouds rippling through it. There was a crackle sound in the air. As he looked up a piece of grey ash drifted down towards him.

‘Hello you, there,’ a voice called up to him.

Standing under the lamppost across the street, lighting a cigarette, was his Uncle Billy.

Tommy threw his toothbrush into the bathroom, went downstairs, put on his shoes and coat, and went out the door. His Uncle Billy was a few steps up the street. He turned at the sound of the door being locked.

‘I thought you might be up and about,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘That could have been why I was lighting that fag there.’

‘I haven’t seen you for ages,’ said Tommy.

‘The same thought I had myself,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘Is all all right?’

‘As good as it could be,’ said Tommy. ‘What’s the red stuff in the sky about? What’s on fire now?’

‘It’s like it’s up in the Square,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘We could go on up and see. Have a juke.’ They turned and walked on. ‘It’s great to take a wander again,’ he said. ‘You and me knocking about, like in the olden days.’

‘It is,’ said Tommy. ‘It is. Old days.’

They kept on going up Park Road and Church Street, the sky overhead spectacular, living, dotted with sparks, scented with burning wood and the destruction of something. A building. The rushing, crackling sound grew. They turned the corner into the Square.

‘God. It’s the picture house,’ said Uncle Billy. He went further up the street. Tommy, his lips parted, followed him. ‘That’s shocking,’ said Uncle Billy.

In the Square thirty or forty people of all ages and both religions stood together watching the Castle Cinema burn down. A fire engine was opposite The Wine Shop. Firemen in wide yellow trousers, big helmets, moving like boys dressed as full-sized men, pumped water in from a distance. Two policemen stood out in the street. An Army patrol sheltered here and there in shop doorways. An ambulance was pulling away. There was no siren on.

‘What do you say, Tam?’ said Uncle Billy. Tommy, his eyes wide, licked his lips, and said nothing. He was listening to the talk around him. A man and woman had been injured as they passed the doors of the cinema. There were no names.

Somebody said, ‘I hear there was a wee bang.’

‘Aye, you never know,’ said somebody else quickly. ‘Whatever it is.’

The roof of the cinema was still on and the walls standing, but the flames were shooting up higher than the walls. Black smoke poured out of the shattered front double doors and straight away took a sharp turn towards the sky.

‘See there?’ said Uncle Billy. He was pointing. ‘The emergency exit’s open.’ Down the alley at the side more black smoke poured out. ‘It’s an emergency all right.’

The small men-figures were spreading more hoses across the Square below the war memorial.

‘I remember seeing Darby O’Gill and the Little People there,’ said Uncle Billy. He was looking up at the flame and smoke and sparks in the sky. ‘The banshee riding in the night sky.’

‘Did it look a bit like that?’ said Tommy.

‘It did. Right like that.’

‘I used to like all them oul Westerns,’ said somebody behind him. ‘They were great, so they were.’

‘I haven’t been for years now,’ said somebody else.

Another voice said, ‘Maybe that black smoke’s coming from oul classics like Buster Keatons and Laurel and Hardys. All them men.’ It was a younger voice than the first.

Tommy stood picturing ancient celluloid flaring up into light for the last time. When he turned round to see who had spoken there was a face covered thick in freckles, somebody a couple of years older than himself. He had seen him before, talking to Damien the Castle Cinema projectionist. The man with the face of freckles had a big grin on. He didn’t seem that troubled that his friend hadn’t a job any more.

‘It might only be George Formbys. Or Norman Wisdoms,’ said Tommy. ‘It wouldn’t matter that much then.’ The face of freckles looked straight back at Tommy and the smile went away and the mouth said nothing. They examined each other. Tommy turned away again.

‘Is that right?’ said the young freckled man, loudly, closely, into the back of Tommy’s head.

‘Come over here for a better look,’ said Uncle Billy. He took Tommy’s elbow, steered him half a dozen steps away to the side. ‘I think that black smoke’s the same you always get at these things,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘This stuff’s the oul carpet and seats and wooden floors and walls thick with nicotine and paint burning. Forty years of cigarette butts down the back of the chairs. I don’t think it’s the gems of Hollywood lost for ever.’ He searched his jacket pockets again for cigarettes, took out his packet of Silk Cut and held it still. ‘That boy with the freckles is worth a watching,’ said Uncle Billy. He lit a cigarette. ‘But there’s no harm in Damien the brother.’

Across the road the roof collapsed and there was a roar of timber falling and the rush of hot air escaping and firemen scuttling back. There were cheers and jeers from the crowd. The firemen came back to pump water over what was left. The flames roared higher than ever.

‘This’ll be a bitter night for being out and about at this hour,’ said somebody. ‘Once we’re away from this good fire.’ There was a laugh.

‘It’s a night for lying sleeping and scratching yourself,’ said somebody else. ‘I’m going home there now. All over bar the shouting.’

‘Who do you think it was, Uncle Billy?’ said Tommy.

‘Aw, it could just have been an accident,’ said Uncle Billy.

‘It could have been anybody,’ said Tommy. ‘The Protestants could have done it because of who owns it. Or it might have been the IRA to make the government pay the compensation. Or maybe it was for the insurance. There’s less people going in there all the time. The television.’

‘Sure it was just a gas cylinder exploding or something,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘Nothing. We’ll go away on home to our beds ourselves.’ He took Tommy’s arm again and steered him another half dozen steps away from the crowd, back down the Square towards Church Street. ‘I can hear the lorry and the Cappagh bins calling me already.’ He bent over. ‘You don’t want to be doing that sort of thinking out loud here,’ he said.

Somewhere down Church Street he spoke again. ‘There is one thing we can be sure about after tonight,’ he said. ‘It’s that now it’s the telly vision or nothing.’

‘And that it’s not going to trouble Uncle Joe much,’ said Tommy.

Uncle Billy looked at him for a while. He nodded. ‘Right,’ he said.

He heard Uncle Joe come in sometime towards morning. There was the sound of staggering, of shuffling feet, and he waited for the sounds of Andy Bap. But Uncle Joe was alone. Tommy turned over and lay there. He closed his eyes.

Inside his head he saw a raven. A shadow on the bedroom floor. There was a tapping…

He opened his eyes again. Uncle Joe, and Andy Bap, and the Castle Cinema. He lay going over and over his thoughts. He didn’t sleep any more.

He got up early, and when he came down Uncle Joe was at the kitchen table. His face was flushed and the eyes and cheeks had matching red threads of veins. There was a smell in the room like a sick dog’s breath. Uncle Joe was drinking coffee.

Tommy didn’t know what to say to him. There was still no sign of Andy Bap.

‘I drank too much last night,’ said Uncle Joe. Tommy moved back to the doorway. ‘I started at half six and sat here all evening just keeping going on the Bush.’ Tommy said nothing. ‘Then I went to bed about eleven. I watched television before that, but I can’t remember what was on.’ Tommy was silent. ‘WHAT THE FUCK WAS ON?’

‘Kung Fu,’ said Tommy. Suddenly he was in tears.

‘Grow up, you cry baby,’ said Uncle Joe. ‘I just shouted.’

Tommy face was pale. He put a hand to his mouth.

‘What are you crying for?’ said Uncle Joe. ‘You know nothing about anything.’

Tommy walked out of the kitchen and back up the stairs.

‘You’re all right, I tell you,’ called Uncle Joe after him. Tommy closed his room door and sat on the edge of his bed. There was another call. ‘Make me some breakfast. Make me some fried eggs. Or something.’

Twenty minutes later Tommy came down the stairs again.

‘I need my breakfast,’ called Uncle Joe as Tommy came near the kitchen door. ‘There’s work to be done.’

Tommy went on past the kitchen and out of the front door.

On his way home from Dawson’s in the black wet evening he crossed John Street to the bottom of Lower Scotch Street as he always did. Across the road in the closed doorway of Duggan’s the bookies was Uncle Billy in the big boots and donkey jacket, standing in out of the rain. He waved Tommy over.

‘I was watching out there for you,’ he said. ‘Wasn’t that crack the other night?’

Tommy stood there. He had nothing he could say. He watched the drips of rain fall from the bottom of Uncle Billy’s donkey jacket.

‘The water’s running out of you,’ he said eventually. ‘You never have a cap.’

‘Aye. Well,’ said Uncle Billy. He didn’t seem to have anything to say himself now.

‘Out in all weathers and you never have a cap,’ said Tommy again.

‘Plenty of thatch,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘You’ve no cap yourself.’

When Tommy looked up Uncle Billy was watching him closely, the bushy straw eyebrows meeting, his lips tight. ‘You’re not asking as many questions the day,’ he said.

‘No,’ said Tommy. ‘No.’

‘I see,’ said Uncle Billy. He ran his hand over the front of his long wet hair, moving the fringe around. ‘You know the way of it then.’

After a while he said, ‘Did you hear about the couple took away in the ambulance?’ They both watched a car approach. It keep going, slowly, a swish of water under its tyres. ‘They were coming down from cleaning solicitors offices on up the Square,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘The O’Reillys from Lisnahull. The pair of them.’

Tommy cleared his throat. ‘There’s both of them dead,’ he said. ‘I heard that. I heard that at work.’ He was making an effort. ‘Maybe they came over to see what was on in the pictures,’ he said.

‘I suppose they did,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘More than likely.’

‘That’s all it takes,’ said Tommy.

‘All it takes,’ said Uncle Billy.

‘What’s to be done, Uncle Billy?’ said Tommy.

‘It’s the way things are,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘But I wanted to say…’ He stopped. ‘Listen. You know there’ll be a payback, don’t you?’ Tommy was looking at Uncle Billy’s lips moving. ‘One of them tit for tats.’ Tommy was hearing every word Uncle Billy was saying, and at the same time he was somewhere far away. ‘Some Protestant getting out of the car at his house’ll get it. Somebody walking to work, maybe. Somebody opening the door to a rap. People who likely enough had nothing to do with this. You have to be careful.’

‘I always am,’ said Tommy. The rest of his mind was still elsewhere. All these things he knew already. Everybody knew already.

‘But more than usual,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘Do you hear me? Joe and his friends’ll be canny enough. They’ll be staying out of The Purple Heather and The Bucking Bronco for a while.’

‘I’ll be fine,’ said Tommy. ‘It’s you up round Cappagh, emptying the bins.’

‘I’ll be rightly. They know me up there…’

‘That’s worse,’ said Tommy. ‘You have to watch yourself. Take a day or two off.’

‘Naw, naw. It’s you going across to Dawson’s,’ said Uncle Billy. ‘Walking to and from every day. Near the Donaghmore Road.’

They stood on there for a while side by side in the bookies doorway, looking out at the empty street, the wet auras of streetlamps, the rain, each thinking about the other one.

May 8, 2014

The power of Eurovision

My finger hovers over the V. I have never typed this name before. Nor written it, nor said it. I press the V. But this name has flitted through my mind for years. A small i. It was around somewhere as I grew into adolescence. Small c. Had my first jobs, packed eggs and loaded lorries. Small k. When my father died, when my mother died. I press the y. The name went with me when I moved from Northern Ireland to England.

L. Partners coming and going. A child born. Another child. The e. I don’t know where it came from. Or where the partners, the children went to. I don’t know why I haven’t looked it up long ago, and I don’t know why I’m doing this now. A lot of fuss over a foreign-sounding name. And I’m very sober this dry, dry evening. The a. Not sure of the spelling, and thinking. The n, then d, r, o, s, quickly.

It’s typed. I look at the screen.

Vicky Leandros.

I click ‘search’.

There are many videos of her. One is of the Eurovision Song Contest, March 25th, 1972, Edinburgh, and a song called Après Toi. I have never watched the Eurovision Song Contest, but I’m less surprised at seeing this than I think I should be. 1972. So many years. God. It is in black and white. I click, and click again, and it fills the screen.

For a couple of seconds there is a shot of an audience. Men with side burns. Comb-over hair. Bouffant-haired women. A man’s voice says her name: Vicky Leandros. He continues to speak in a foreign language. I’m watching more than listening and I don’t recognise the language. The framed face of a young woman, pretty enough, with long dark hair, is projected on a screen on stage. Her name is below. I accept it is her, but it could be any pretty young Mediterranean woman. It doesn’t explain anything. The man with the European language talks rapidly on and on. The only words I recognise are ‘Vienna’ and her name again, repeated, as if two pronunciations are possible: Leandros and Leandro.

I am being shown part of the audience and part of the orchestra pit. Between the two is a hanging, twinkling curtain. The voice talks on. The words spill out over the shadowy people, the silly curtain. It all looks small scale, amateurish. The hanging twinkling curtain parts and a man with large glasses and long thick fair hair walks out between orchestra and audience. He steps up onto a little podium and bows to the audience. The rail of the podium shakes as he bows.

The projection of the pretty girl on stage has been replaced with the words ‘Après Toi’. I wouldn’t have known what they meant in 1972. A man begins to dart across in front of the words, and then goes back. It all adds to the air of amateurishness.

The camera pulls away and I can see the stage for the first time, and it is only just in time, for a slim young woman in a long dark dress is already walking out in front of the cameras and the audience. She walks quickly, confidently. Her right arm swings once, up and ahead of her. She stops. The spotlight has thrown an oval on the floor behind her, and her shadow, like her, slim and dark, stretches out across the oval.

Vicky Leandros. Knowing her name and nothing else about her for forty years has alone given her mystique and gravitas.

The commentator in his European language seems to say ‘rosy fingers’, but I doubt this, and then he stops talking. Immediately the orchestra pumps out music. Poomp poomp poom.

I must have seen this before. This exact performance, minus the foreign commentary. Sitting, on what was surely a Saturday night, in front of a television with my parents in their house in Milltown Street, Dunmaddy, Northern Ireland.

I’m shivering a little. All the why questions are running in my head. It’s like I have found an old diary, I’m reading about something that was once important to me, and I can’t understand why it was ever important, and why it was then forgotten.

She seems a little hunched, but it is the raised shoulders of the dress. I am hearing her voice before I realise she is singing. She sings softly. Tu t’en vas. You are leaving. The camera is coming in closer. It could not come in close enough. She is beautiful. A serious, beautiful, face.

The camera comes closer still. The voice is not strong, but the image and the sound fill me. I see her hand holding the microphone, the small pale fingers, a ring, like an engagement ring, on her middle finger. The long waving dark hair cascades, yes, about her face. Her eyes close, her mouth makes a bow shape, opens, and now her singing erupts: Qu’après toi…

And I look at her, and my heart moves in me, as it surely must have done on that night in Dunmaddy, in my twelve year old self. Very little moves me, and this is moving me. It’s not comfortable. I watch the dark hair, the face, the little curve of the nose, the bow mouth that spills out wonder and tenderness and sadness: … je ne pourrai plus vivre, non plus vivre qu’en souvenir de toi. After you I cannot live, not live only in memory of you. Her right hand, the back to the audience, rises level with her face, and descends and the fingers ripple as the hand comes down. The fingers have twinkled, and there is nothing cheap about it. She continues to sing and I am not translating any more. The sound is, as it must have been then, sense enough. As her voice falls at the end of this verse her face breaks into a smile. She is making a beautiful thing and knows it and should smile.

Was it at this moment on the sofa in Dunmaddy that her name, the only words I could understand, became so firmly hung on that peg in my head? My thoughts shoot away from the video and to Northern Ireland in 1972. What was happening then? But I have spent many years making sure those things haven’t stayed on any pegs.

She is facing me now. Her right hand begins to ascend once more, slowly, to level with her face, the back of the hand to me. It hovers, then descends swiftly. I am fascinated.

I would have known then, as I read on-line on the morning after this evening, that, up until this Saturday night ninety people had been murdered in Northern Ireland in 1972, thirty one of them in those first twenty five days of March alone.

I would have known then that five days before this night a 200 pound car bomb had been detonated in Donegall Street in Belfast city centre, murdering seven people and injuring one hundred and fifty more. Two of the dead were policemen trying to evacuate the area. Three were binmen, blown off their bin lorry. Two were old age pensioners.

I hear the words ‘après toi’ again and again. There is a large brooch of leaves and berries on the high-necked dark dress. The dark hair falls and curls against her cheeks, the smooth skin pale against the dark of the hair and the dress.

I would have known then, as I watched this before, that a little later on that same day as the car bomb a sniper fired a single shot and murdered a soldier.

Now her head and the hand holding the microphone fill the screen. I can see her sad, serious, heavy-lidded eyes. The camera is pulling back. I try to think about this singer and song, what it has meant and what it means to me now, but the desire to watch and listen overwhelms the desire to understand.

I would have known then that two days before that night the army shot and murdered a thirteen year old schoolboy in Belfast. A petrol bomb was found nearby but no evidence he had ever touched it.

And the voice rises once more, and once more the right hand rises with it, the fingers ripple, the hand descends. Yes. And again, as surely I was on that Saturday night forty years before in Dunmaddy, I am full of both sadness and joy. It is hard and shocking. I inhale and forget to breath out, and then jolt back into sense.

The murders on the day she sang were even more ridiculous and avoidable and banal. I imagine Vicky Leandros waking about seven a.m. to rehearse, to prepare herself, a long day ahead, in Edinburgh on the far side of the short strip of water that is the Irish Sea. About seven a.m. in Springhill Avenue in Belfast a man was accidentally shot by his friends, and trailed into a house. The woman who lived there came downstairs and found his body in her living room. He had been somehow accidentally shot by twenty-four bullets of three different calibres.

Après toi je ne serai que l’ombre… the camera is pulling back… de ton ombre… The song is nearing its end. Even I, unmusical, know that. Her right hand is rising in a wide sweep, moving out, around… Après toi. The hand descends suddenly and her song is over. There is applause, much applause, and she is looking up. It is over for her, and beginning. Her head moves just a little to her left, then forward, and she bows. Then the audience, over-dressed, over-permed, stiff in their seats on what looks like a balcony, but applauding, a couple looking at each other, the stiff applauding going on and on.

The other murder on that March 25th was in another part of Belfast, around the time Vicky Leandros sang. A man had gone to the Shankill Road UDA club and complained about the beating of a friend. Were the drinkers watching this on television too? The man who had done the beating shot him in the head.

Not a thing of these incidents when Vicky Leandros sang in Edinburgh, or anything about the other four hundred and ninety six people murdered in Northern Ireland that year, has stayed with me. That might have been the year the IRA shot me in the arm. It was some year around then. I can’t remember. I have succeeded in not remembering, in making the petty, deadly, things nothing to me. But I have remembered this singer’s name.

Sitting there after the song finishes I do remember some of the stratagems for survival in Northern Ireland in 1972. Draw the curtains before putting the house lights on. Keep the car interior light permanently off. Never stop walking if someone pulls up in a car to ask directions. Don’t open anything you might find. Never answer any knock at the door without first checking. I would have known many more then, yet never enough. That was life, as we walked and talked and went to school and work, and watched the petty, deadly things come up to our own door and then turn away, maybe this time, maybe not the next. And while we waited for that knock we watched light nonsense on television, and I saw Vicky Leandros make a little, important, bit of wonder in a hall in Edinburgh.

I’ve timed the video. From the music starts until she stops singing is 2 minutes 48 seconds.

Over the next hours of this evening I play Après Toi in English, where it is supposed to mean Come What May. The English words are happy and so wrong. I hear it sung in German, in Greek, in Spanish. I watch and hear a Vicky Leandros, recognisable, stranger, harder somehow, a performer, sing it in 1992 and 1995. I watch and hear her, over the years, always attractive, never magical, sing many other songs in a range of languages. I watch her with bobbed hair five years before that night in Edinburgh singing another entry in another Eurovision Song Contest, a song called Love is Blue. She looks full-cheeked and what she is, a very young woman with heavy makeup.

There is nothing to drink in the flat. I could go out for a bottle of something. But it’s late and I don’t want to walk the streets. Among these foreigners, I think. The English. Or go to bed and lie awake. Instead I go back and watch the black and white video again. As I watch I see things I missed first time around. I watch again as her face breaks into the smile after the first crescendo. I freeze the frame, and look at that face as the lips begin to close. Yes. She knows she has done this well. Does she know how well? I watch the gesture of the hands, the fingers rippling, the brow furrowing, the lips changing shape. Seeing the effects work over and over does nothing to lessen them. I expect them, I think I understand them and, on this created, crafted, constructed thing, they work again and again.

Later, way into the night, I think: what happened to the long dark dress? Does she still keep it, in a wardrobe, the dress she wore when she broke through and became… whatever she became? Was there a man, a boyfriend, who asked for and got the dress and then maybe in a year, full of anger as she moved on, threw it away? And the brooch of leaves and berries?

I think: in the morning shall I look up what was happening in Northern Ireland around March 25th 1972? Of course I do. It is the cold experience I anticipated. It is what I have told you.

I think: if I was naive to find this song and this singer so beautiful all those years ago then, held up against the stupidity and bigotry and hatred and violence all around me, it was a small naivety, a small stupidity.

I tell myself that on that Saturday night in 1972 I forgot to be fearful for all of 2 minutes 48 seconds, that for that time I was free, and that it was long enough, important enough, for me to carry the name, the one thing I understood, in my head for forty years.

That is what I have told myself anyway. It may even be true.

So I play the video again. I play it again, I play it again, and this I do know: each time as it ends the sadness of something lovely having been lost sweeps over me.

May 1, 2014

Dollarton to Ripe

‘Well, he’s not buried on consecrated ground. He killed himself, didn’t he.’ It wasn’t a question. She was a local woman, in her sixties, walking her dog in the churchyard of St John the Baptist in Ripe, East Sussex. She would know. Except she didn’t know. No one knows if Malcolm Lowry killed himself or if it was an accident. Not Margerie his wife, who later told so many versions of that last night. Nor did this local woman know where his grave was. She led us around the other side of the church, towards the gate where she had just entered. There were two rows of headstones a little apart from the rest. But it was in the churchyard, certainly consecrated ground, despite what she had just said. We walked up and down, bent, squinting. But where was Lowry? ‘It’s here somewhere,’ she said.

‘I’m a little surprised he’s buried here,’ I said, as we read names, none of them his. I meant that after all his travels abroad, his sojourns in Mexico and his creative life in the shack in Dollarton, that he had somehow ended up in this twee, sweet, claustrophobic English village.

‘Of course he’s buried here. He was a parishioner.’ That Lowry was a parishioner in Ripe I doubted. I didn’t ask if she thought he had ever been in the church before they put him in the ground beside it. ‘No. It’s not down that far. There was a plaque on it. It’s not down there.’

She was grumpy, and kept trying to be helpful. I wondered how many others over the years had asked her about Lowry’s grave. ‘Somebody put a plaque on it,’ she said again. ‘It had a volcano on it.’ Of course it would have. ‘It was chained,’ she said.

One grave had a large untrimmed rose bush growing out of it. Long daffodils with dead heads bent and lay across the grave and the headstone. I pulled back the rose bush. ‘It’s here,’ I said. ‘This is it.’ I could just see the blue and yellow of a plaque below. I pulled the dead daffodils aside. ‘There.’ The woman bent too.

‘That’s not the one that was on it. That’s not the one that was there the last time I saw it.’ I tugged at the plaque. It rose easily off the ground and then stopped. This one was held by a steel cable. I couldn’t make out what the picture was. Below it was writing.

‘It’s got something in French,’ I said, half reading it. ‘It’s Spanish,’ said the woman. ‘It would be Spanish.’ Of course she was right. Maybe she had read Under The Volcano.

‘Yes, it is.’

‘There it is then,’ said the woman. She called her dog and walked away. I took out my notebook and wrote down the sentences.

‘¿Le gusta este jardín, que es suyo? ¡Evite que sus hijos lo destruyan!’

In Under The Volcano the Consul, Firmin, finds these words on a sign in a neighbour’s garden while looking for a hidden bottle of alcohol.

‘The Consul stared back at the black words on the sign without moving. You like this garden? Why is it yours? We evict those who destroy! Simple words, simple and terrible words, words which one took to the very bottom of one’s being, words which, perhaps a final judgement on one, were nevertheless unproductive of any emotion whatsoever, unless a kind of colourless cold, a white agony, an agony chill as that iced mescal drunk in the Hotel Canada on the morning of Yvonne’s departure.’

The Hotel Canada. Because of course these words were written not in Mexico, nor in this twee, sweet Ripe, but in a wooden shack in Dollarton on the north shore of Burrard Inlet, British Columbia, Canada.

But he has mistranslated them. They mean: ‘Do you like this garden that is yours? See to it that your children do not destroy it!’ This the Consul realizes later.

I of course had to look this up. The words were familiar, as the location of the grave was to the local woman with the dog, but also like her I could not quite locate them. This plaque, on a closer look, was of a sun and leaves and possibly a hill.

The woman and dog hadn’t gone far.

‘He was drinking the night he died, wasn’t he?’ I said. It wasn’t a question either, but I wanted to know what else she knew, or didn’t know, about this resident of her graveyard. She must think how they would one day share it, no matter what she thought of him.

‘Not in The Lamb,’ she said. ‘He was banned. They walked home from Chalvington, they fought, and he drank a bottle of gin and took all her sleeping pills.’

‘Right.’ She was right. But it’s not known if he took all the pills on purpose or by accident, or if, as he had done on numerous occasions, thought he was taking handfuls of vitamin pills. It was not barbiturates nor alcohol that killed him anyway, but drowning on his vomit. ‘The Lamb’s along there?’ I pointed.

‘Yes. Keep along the road. And the house is down to the left. A white house.’ She was off again, this time keeping going. I took photographs of the grave. We walked to the gate and the road. The woman and dog were just around the corner, walking up and down. Hovering, maybe. Guarding him a little. Or maybe the plaque.

We kept on along the road, past nice, good, clean, old, utterly silent, deserted-looking houses of the country-dwelling middle class. Why wouldn’t Lowry feel at home here? They were his people. But he hadn’t felt at home. He had been yearning to get back to the shack on the shore in Dollarton, the shack where he had survived cold winters with dips in the sea, storms that blew away his home-made pier, a fire that destroyed his cabin and a lot of his manuscripts, a wooden shack where he had written much, including the third and fourth drafts of Under The Volcano. A shack that Margerie never wanted to see again.

Lowry at his Dollarton shack.

He had returned from a holiday in Grasmere longing to be back in that shack more than ever. But they had walked to The Yew Tree pub in Chalvington a quarter mile away, bought a bottle of gin, walked back to The White House, quarrelled, and Lowry had died.

There would be no more hot, wild Mexico. No more cold, wet Dollarton. Only this sweet claustrophobic English village and the yellow and blue plaque put on by a reader, only people like this local dog walker and her mixture of misinformation and information, only the blue plaque on the wall of The White House:

MALCOLM

LOWRY

1909 – 1957

Novelist

lived here

1956 – 1957

April 27, 2014

Blog Tour

My Writing Process …. Blog Tour:

Today is Blog Tour Day. Yip, rolled around again. I’m glad to be back with this update of my previous My Writing Process Blog. My thanks to Amanda Addison for inviting me. Amanda’s current work in progress, Picasso, Cream Horns and Tulips for Alice, is a bitter sweet tale of first love tied up with the life-changing experience of finding your own creative identity, “through being an artist…being someone who notices things,” Grayson Perry, Reith Lecture 2013. This is acted out through the interweaving stories of the two main characters, Mathew Andersen, an 18 year old art student, and his mother, the forty-something Sam who is drawn back into her artistic past. The backdrop is Great Yarmouth, the North Sea, Brighton and Amsterdam.

Find more about Amanda (in whom writing and sewing truly meet, believe me) and her other work in progress here:

Here are my answers to the Writing Process questions.

1/ What am I working on?

I have now finished my second novel, Terminal City. I’ve had feedback from my keen team of first readers, and I am in their debt.

Terminal City is a crime and relationship story set in Vancouver in 1939 and 1959. The 1930s and 40s were the same noir period for Vancouver as they were for LA and San Francisco, the other great West Coast cities of North American. But these cities have been written about from James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler on. Vancouver hasn’t. It’s a period of bank robberies, murders, town hall, police and business corruption, and of campaigns by the ‘right-thinking’ to establish order and conformity. What if I united the criminality of the pre-war years with the white bread and complacency of the late fifties? What if a fading Hollywood star returned to where he had begun, a dying and wealthy man’s desire for vengeance was re-ignited, and a death long forgotten resurfaced? What if lives around them were disrupted? What might all be hiding from the wilder days of their youth?

I’m also, along with Amanda and others, judging the current Rethink New Novels Competition 2014. We met recently to eat Japanese food and make decisions about who will be published. The judging process has been one big informative spell for me and I’m glad to have been a part of it. As a previous winner myself I know what a difference it will make. I’m happy to know that two currently unsuspecting writers will soon be hearing good news, and, severe critic as I am, sad that so many others will have to be disappointed. So much work, such dedication.

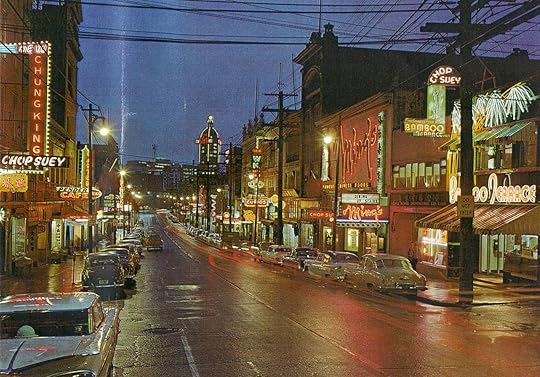

East Hastings Street, Vancouver in 1959, the scene of some of the most important action in Terminal City.

East Hastings Street, Vancouver in 1959, the scene of some of the most important action in Terminal City.

2/ How does my work differ from others of its genre?

Terminal City is a crime story, but at its heart, and at the heart of my previous book, The River and The Sea, as in just about anything I’ve ever written, lies a desire to tell a story of how people need each other, hate each other, love each other and dispense with each other. I see this as the one great theme of literature, presented a few million different ways. It would be this emphasis on the very personal relationships of the protagonists that would make my concept of a crime story different to others of its genre. In Terminal City there is the potential crime of a death twenty years before. There is also the crime of a love betrayed and the lover used. If someone willing allows him or herself to be taken advantage of… have they been betrayed at all?

This feels very much linked to the next question: how does my writing process work. I’m interested in that old banal subject that all of us, we human social animals, are interested in: people, and especially other people. But I need to see them, and show them, in context. My interest in that necessitates them speaking a language I understand, and them living lives I can relate to. I can’t do gladiators or sword and sandal of any kind, ancient Egyptians, Anglo-Saxons, hobbits, magical schoolboys or any of the many imagined entities of superstition: they are all too far removed from my own limited experience for me to have empathy. I just don’t care. Others clearly can. I can’t. A period and location not my own but one with which I can have some understanding, and people whose ambitions, beliefs, hopes, desires, failings I can relate to is what I’m after.

Not really a deviation: I have a wire fox terrier called Finn. Finn has no interest in chasing balls. He won’t swim. He just wants to relate to people and other dogs. I’m a little like Finn. Less dogs, more people, maybe. Here’s a recent photo of Finn. He’s handsomer than I am. Younger. More hair. He’s got it all.

As I say it’s all really about people. Other writers I’ve been influenced by, those I remember and the myriad I’ve forgotten, are writers of the dilemmas and conflicts of flawed, recognizable, believable human beings.

Writing immerses me in a world that is related to, yet different to, my own, with interesting people doing interesting and sometimes dangerous things. Occasionally physically dangerous (a firing squad, shot or blown up in WWI, cold and hunger in The River and The Sea; alcohol and drugs and syphilis, a blow on the head in Terminal City ), but also dangerous in their relationships with those they care about, and/or who care about them. Psychologically I’m involved enough for it to matter, but ultimately I’m safe. Disaster may affect the protagonists but not me. I can even, cowardly, chuck it in and walk away. What’s not to like?

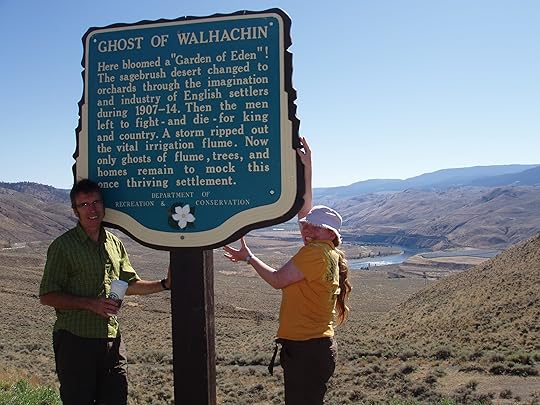

The photograph without which The River and The Sea would not exist.

4/ How does my writing process work?

The process so far has been to get excited about some discovery I’ve just made, and find I want to dwell in that place more and more. With The River and The Sea it was when I found the road sign on the Kamloops – Ashcroft highway describing the town of Walhachin that for a brief pre-Great War period had bloomed there, to vanish at the outbreak of that war. I re-peopled it with its real former inhabitants as best I could from on-line research, reading what little was available, and visiting the site. I wanted to take it further, and added characters of my own creation who would… yes, of course… need each other, hate each other, love each other and dispense with each other.

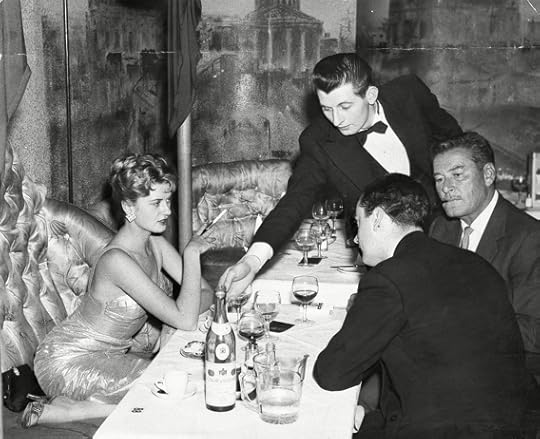

Errol Flynn, the original of Terminal City’s Rory Devlin, on board the Zaca, the boat he came to Vancouver to sell when he was ruined and dying.

With Terminal City it was reading of the death of Errol Flynn in Vancouver, a city whose history I was already studying. He had come there in October 1959 with his 17 year old blonde girlfriend to sell his last possession of any value, his much-loved yacht, the Zaca. What clinched the desire to write something set around this incident was reading that Beverly Aadland, the blonde supposed bimbo, never sold her story, maintained her dignity, and seems to have truly mourned the fading roué that was Errol Flynn. It was an opportunity to spend time in that pre-skyscraper city in which I was already involved, see its first tall buildings go up, ride in its cars, feel the tram tracks on its streets, hear its music and its people speak.

Errol Flynn and Beverly Aadland, 5th May 1959. Errol Flynn was purportedly to have said: ‘I like my whiskey old, and my women young.’

Errol Flynn and Beverly Aadland, 5th May 1959. Errol Flynn was purportedly to have said: ‘I like my whiskey old, and my women young.’

So it’s excitement about some real location and/or event, followed by a need to see the people involved as best I can. During this research characters fitting the location and period develop, begin to take on desires, hopes, failings. They make decisions: some pan out, some don’t, but the characters, if it works out how I want, are off and running, growing into what I hope will eventually by a coherent novel-length narrative.

These initial stages are happy and free. Then comes the harder work of putting these scenes, already existing in notes, written sketches or just inside my head, down in the most original, involving form I can come up with. It has to have a destination, which I know before I begin this stage. That could be five or six months work, but of course the thing has been floating around somewhere in my head for a couple of years by then. Once that draft is in place then pleasure returns: the polishing, honing, paring, the re-writing, aiming this time round, maybe, for something a little neo-noir, a little Dennis Lehane, a little Gone, Baby, Gone meets Gone Girl? Basta! Basta!

Flynn and Beverly, Vancouver Airport, October 1959. Nearing the end.