Isham Cook's Blog: Isham Cook, page 2

December 3, 2021

The state of rage: The American sexual dystopia

Police in Sacramento, California, greet a registered sex offender. (The Associated Press.)

Police in Sacramento, California, greet a registered sex offender. (The Associated Press.)Let’s say you believe that the heterosexual monogamous family unit is the only proper place for a sexual relationship, and virginity for women and sexual abstinence for both sexes before marriage is appropriate and even essential. You believe adolescents have no sexual rights of their own and must be shielded from sexual knowledge and experience before they reach the age of consent (sixteen to eighteen years in the U.S., varying by state). You believe casual sex, serial lovers, simultaneous relationships, and the like, are reckless and dangerous, or at the very least immoral. You believe sex to be not very important in fact, a mental obsession and addiction, easily subdued with a focus on the more meaningful aspects of life. But you also believe sex to be enormously important, inasmuch as sanctioned sex is holy and unsanctioned sex is often destructive to all parties.

If you hold to any of the above, I’d wager you’re a traditionalist and fairly conservative, if not necessarily religious. Communist regimes would find all of the above most salutary, and fascist states like Nazi Germany were especially fond of controlling sexual behavior through such strictures. But they can be found in many countries, and as one looks back in history, sex laws were even harsher. In Elizabethan England, for example, adultery was punishable by death; in Medieval Europe, the Church dictated which days of the calendar couples were permitted conjugal relations.

Now ask yourself if any of the following applies to you as well. You believe that there is no place for family nudity, and women must tone down their raw allure by shaving their legs and underarms and wearing a bra, while it’s okay for men to go about topless. You believe the public sight of a woman’s breastfeeding nipple is obscene. You believe perceived improprieties of any sort should be referred to grievance committees instead of dealing directly with the offending person (we don’t mean criminal assault or rape when we need to resort to the police). You believe the police should be informed if teenagers close in age are caught having sex, above all if one is above the age of consent and the other is not, and that it’s acceptable for children of any age to be punished and even prosecuted if they engage in sexual harassment or assault. You believe sex work is degrading and prostitutes and their patrons should both be arrested. You reserve special loathing for pedophiles, who if they can’t be locked up for life, must be exiled permanently from society, regardless of the severity of their offense. You would troll the national and state sex-offender registries for newly listed offenders and their families to hunt down and attack. You believe all of this while regarding yourself as otherwise liberal and enlightened, in our day and age, toward gay and transgender rights, extramarital sex, and other practices that only a generation or two ago were deviant or unlawful.

You would troll the national and state sex-offender registries for newly listed offenders and their families to hunt down and attack.

No one country has a lock on these sentiments, but what’s salient about the American response to sexual prohibition, as it is currently characterized and defined, is its fanaticism, its eagerness to find fault where there is none, and the ensuing rage where it is found. In the name of being progressive, Americans are particularly susceptible to sexual fascism. As Theo Horesh remarks in The Fascism This Time, “liberals are carrying out their own paradoxical crackdown on sexual freedom. The criminalization of relatively minor infractions of sexual norms; the severe crackdown on borderline cases of sexual harassment; the pathologization of late-adolescent expressions of sexuality.” Because the U.S. has a long, Puritan-inspired legacy of intolerance toward the sexually rebellious (Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter is the iconic example albeit one that pales in comparison to the punitive response toward today’s sexual deviants), a legacy backed by widespread popular support, it’s easy for the state to latch on to sex law as a ready means of expanding its regimes of surveillance over everyone.

Now consider a few examples of sex crimes and their punishment, pulled off the news almost at random, there being no shortage of stories. We’ll begin with a clearly egregious yet not wholly unambiguous case and work our way through increasingly problematic ones. Several years ago, a 46-year-old Indian American physician, Shafeeq Sheikh, was convicted of the sexual assault of a 27-year-old patient whose breasts he had fondled while she was medicated but conscious and receiving treatment for asthma in a Houston hospital. He later reentered her hospital room and had unprotected sex with her. He claimed it was consensual; she claimed she tried to report the assault by summoning the nurse with the call button but was too weak to do so until the next day. Mitigating circumstances led the jury to downgrade the rape charge, which in Texas normally carries a prison sentence of two to twenty years, to a mere ten years’ probation. That Sheikh wasn’t given any time behind bars sparked media outrage at the miscarriage of justice. News reports did take care to mention that he lost his medical license and would have to register as a sex offender (G. Banks).

The mention is significant, for Sheikh might be better off in prison, where at least he would be in a relatively stable environment, protected from the elements (if not from violent fellow prisoners) and provided with daily food and bedding. If the public understood what his punishment actually entailed, they might be a bit more persuaded justice was served. His listing in the Texas Public Sex Offender Website shows his photo, risk level (low), duration he will be registered (lifetime), date of birth, address, crime (sexual assault), sex and age of his victim, and the date of the offense. That is, although his probation ends after ten years, he will remain on the registry for life, and his address will ever be available to anyone with an internet connection (he’ll have to register his new address whenever he moves). As the offense didn’t involve children, he and his family may be spared attacks by vigilantes set on driving them out of the neighborhood, say by throwing rocks through their windows. Crimes on the registry are stated in broad terms, so that, for example, an 18-year-old caught having sex with his 17-year-old girlfriend in a state where the age of consent is eighteen might be listed as having taken “indecent liberties with a child.” Some state registries don’t list the victim’s age, so anyone viewing such an offender’s profile could reasonably assume he is a dangerous child predator, inciting the community to force him out, if he’s allowed to live at home to begin with (No Easy Answers).

And because the registry’s purpose is to alert the neighborhood to predators living in their midst, all listed offenders are subject to the same community restrictions, regardless of whether their crime involved children. In every state, sex offenders must keep a specified distance from places where children congregate, on pain of a felony conviction for violating the restrictions. In Texas, they may not reside or approach within 2,000 feet of any park, playground, school, day-care center, video arcade, youth center, recreational hiking or biking trails, or public swimming pool. These restrictions are often designed with the express purpose of zoning offenders out of their community or city altogether, including from their home; they may not be able to live at home in any case if they’re forbidden contact with their own children.

The restrictions that specifically apply to Sheikh would have been decided by his probation board and the Houston police. If he is allowed to live at home with his wife and child, he can consider himself extremely lucky. If not, he will probably find it difficult or impossible to rent an apartment, not only due to residency restrictions; landlords do background checks and routinely reject anyone on the registry. Whether he will be able to find employment to help support his family and pay for the array of monthly probation and administrative fees he’ll be saddled with is also uncertain: employers likewise all the way down to fast-food restaurants refuse to hire anyone on the registry. The upshot is that as a consequence of allowing his hormones to get the better of him while doing his rounds one night at work, Shafeeq Sheikh may be reduced to life in a rural trailer park or under a highway overpass not covered by residency restrictions, supported by the very family whom he had been supporting before his arrest. If his wife is herself unemployed, if their home has a mortgage, then she and their child may themselves fall into dire straits, possibly rendered indigent. If Sheikh is denied housing altogether, he could be reduced to joining a band of fellow sex offender vagrants adorned with GPS ankle bracelets as they wander from community to community, or city to city, to find shelter, their exact movements tracked by the police (homeless shelters often turn away sex offenders). Milwaukee was one such dumping ground until it tightened up its residency restrictions in 2014, forcing some 200 registered offenders out of the city before they were allowed back in 2019 (Faraj; Hess).

Was Sheikh’s crime so heinous as to deserve such punishment? Measured against the worst types of sexual assault, say violent rape causing serious injury or death, clearly not. He may truly have misread the situation and deluded himself into believing the sex was consensual. This does not of course excuse his offense, but suggests that it wasn’t premeditated; nor does he fit the typical profile of a dangerous predator, with a history or pattern of prior behavior. It is therefore hard to see how such a draconian punishment, reminiscent of something out of medieval history or a Third World theocracy, fits the crime and what it accomplishes in terms of public safety. In almost any other country, the punishment for the same offense would fit the crime; even if incarcerated, the offender would be allowed to reenter society and be provided with the necessary support for doing so upon his release.

It is hard to see how such a draconian punishment, reminiscent of something out of medieval history or a Third World theocracy, fits the crime and what it accomplishes in terms of public safety.

Another example of the momentous consequences of a stupid but fateful decision sprung from sexual temptation is the case of Jace Hambrick. A 20-year-old gaming nerd from Vancouver, Washington, he responded to an ad posted by an attractive woman in the “Casual Encounters” section of Craigslist. Oddly, in their initial exchange, she told him she was thirteen. He didn’t believe her, assuming some kind of a tease, as it bore no relation to her photo, the sophistication of her language, particularly about sex, and her knowledge of gaming. She invited him to her house. She greeted him outside and lured him in. Upon entering, he was subdued by armed officers. She was indeed the woman in the photo, a 24-year-old undercover police officer. Despite not getting anywhere near her (nor was any other incriminating evidence found in his electronics), Hambrick was sentenced to eighteen months to life in prison for the attempted rape of a child. Most people convicted of similar charges through such entrapment stings do a minimum of ten years in prison (after plea-bargaining), but he was lucky and released for good behavior after two years. The terms of his probation as a registered sex offender, however, are onerous and to the extent of destroying his career, almost as bad as prison. Although he may live at home, he is not allowed to visit shopping malls, movie theaters, sports venues, parks, or anywhere children congregate; at home, he is forbidden from drinking alcohol and must inform a prospective partner that he’s a registered sex offender. During his decade on the registry, he will have to pay the state $28,800 in probation and counseling fees. He has not been able to find work, apart from brief temporary gigs. After ten years he can apply to be removed from the registry, with no guarantee he’ll be approved (Winerip).

The next example of judicial sadism is more ambiguous still, or rather unambiguous, at least from a considered perspective, since the actual offense cannot under any rationale be considered a crime. Caught having consensual sex with two sixteen-year-old teenage boys at a camp in Idaho at the age of eighteen (sixteen being the age of consent in Idaho), Randall Menges was sentenced in 1993 to seven years in prison for sodomy. Upon his release in 2000, he was placed on the Idaho sex offender registry. Years later he moved to Montana, requiring him to register as a sex offender in that state as well. During all these years, he has been denied employment and housing, has had to live in “homeless shelters and had to sleep on the streets.” Finally in May 2021, almost three decades after his conviction, a Montana federal judge removed him from the registry on the grounds that “the harm Mr. Menges suffered under Montana’s statute outweighed the public’s interest in keeping his name on the registry.” However, this was immediately appealed by a state prosecutor, and Menges’ legal situation remains in limbo (Cramer).

The state’s rage is perhaps no better exemplified than in the recent case of a seven-year-old boy in upstate New York who was arrested on a rape charge. The child’s identity is being protected and no details of the case, presumably innocent sex play with another child, were revealed. But even if it involved, say, his sticking something into the other’s orifice, clearly this cannot under any reasonable grounds be considered criminal behavior. A defense attorney, “citing cognitive science data showing that young children lack a true awareness of what they are doing and the consequences of their actions,” made the obvious point that “‘the science doesn’t support prosecution of second graders’” (Nir). Levine and Meiners lament this astonishing penchant of the American state for branding young children as sex offenders:

Toddlers as young as two were being labeled as children who molest and treated for “inappropriate” behaviors like putting objects inside genitals, pulling down their pants in public, or masturbating “compulsively.” Some were being prosecuted as sex offenders. In fact, almost everything these children do—rub their bodies against other kids, expose themselves, insert things into orifices—can qualify as normative children’s play. And even those children who do harm to others sexually almost always show signs of aggressiveness in other ways as well—hitting, abusing animals, setting fires. The problem is the aggression, the cruelty, or the inability to control their impulses—not the sex.

Luckily, the seven-year-old is too young to be placed on the registry in New York, whose threshold is thirteen, but Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas register children as young as eight, and Massachusetts as young as seven. One-tenth of the 900,000 people on the sex offender registry in the U.S. are children (McKay; Stillman, “The list”; No Easy Answers).

In the public imagination, at least to those even aware of its existence, the sex offender registry is a well-deserved repository or garbage dump rightly reserved for monsters wholly beyond the pale of humanity. But it has become remarkably easy for almost any normal person in a stupid or thoughtless moment to get on the registry. Innocently patting a child on the butt; mooning or streaking during a drunken night out; urinating in public even after taking precautions to conceal oneself but caught on camera; accidentally stumbling into a woman’s restroom or unlocked apparel changing room with someone in it; teenagers of the same age having consensual sex or sexting their nude pics to each other; prepubescent schoolchildren caught pulling down their pants; sleeping with a minor who falsely claimed with a fake ID she was eighteen; a massage therapist who grazes a customer’s breasts; an unknowing family member or parent of a sex worker accused of aiding and abetting sex trafficking by living in the same home: these are some of the offenses that can get one put on the registry. Not that these acts will necessarily get you on the registry, but it can definitely happen, and once you’re on it, it’s basically all over for you.

Sex crimes do of course vary in gravity from the benign to the violent, and the law attempts to reflect this. The national sex offender registry implemented by the Adam Walsh Act in 2006 distinguishes between more serious Tier III (aggravated sexual assault, sexual abuse of a child under thirteen) and comparatively less serious Tier II and I offenses. Yet sentencing varies widely and can be arbitrary and capricious, and states may and often do boastfully override this with stricter registry restrictions than the federal requirement; states are not allowed to impose restrictions less strict than the national registry. When sex offenses by grown teenagers or adults are truly abusive or violent, the state’s expected role is to determine the proper treatment for the offender and, if necessary, sequester him for the community’s safety. On the other hand, when politicians enact laws expressive of the public desire for retribution, and these laws become institutionalized and normalized, when the state backs the public’s desire for revenge and becomes at one with the vengeful public, the state itself takes on a vengeful cast. We are then on precarious ground. This is what is happening in the United States.

We look to artists and writers to put their finger on the pulse of their times. The South African novelist J. M. Coetzee memorably captured the ease with which sexual improprieties can turn tragic in his 1999 novel Disgrace, featuring a university professor who sleeps with one of his students under ambiguous circumstances, neither wholly consensual nor wholly coercive. He is fired, not for the offense itself but for his refusal to acknowledge the offense, and the rest of the narrative follows his mental unravelling and descent into poverty and degradation. An American version of the sex offender protagonist is the Kid in Russel Banks’ 2011 novel Lost Memory of Skin, remarkably prescient of the 2017 Jace Hambrick case noted above: a 19-year-old man meets a teenage girl online for sex and neglects to find out her exact age. The story is set under the Julia Tuttle Causeway sex offender colony in Miami-Dade County in Florida, the only place the Kid is permitted to live after his release from prison, along with his pet iguana and portable generator for keeping his ankle bracelet charged. High schools are prime territory for sex scandals, as in the 2007 film Look (dir. Adam Rifkin), with its clever conceit depicting the entire action through the lens of security cameras. A cynical teenager just under the age of consent sets out to seduce her teacher just to see if she can pull it off. She succeeds and sends him to prison. The high school sex scandal in Zoe Whittall’s 2016 novel The Best Kind of People similarly portrays a respected high-school teacher who is jailed for propositioning one of his students, though here the focus is on the devastation to his ostracized family in the face of the community’s rage.

These authors have not needed to resort to invention, as if concocting unique little Greek tragedies for our moral edification. Their task, as chroniclers of our time, is not hard. Their tales are all clearly based on real events, of which there is no shortage. What makes them especially foreboding in the American context is that the collective fury proceeds from the community rather than the government. The rage of the state is one defining feature of fascism; the state of rage is the other, when the state offloads its rage onto the public, delegating to it the task of retribution. The less the public understands this and experiences this rage as its own, the more efficacious a tool of the state it becomes.

The rage of the state is one defining feature of fascism; the state of rage is the other, when the state offloads its rage onto the public, delegating to it the task of retribution.

Daily news stories of capricious rage over wholly manufactured sexual accusations abound, such as the high school teacher in Maine who was falsely accused of sleeping with her seventeen-year-old male student and not rehired after being fired, despite being fully exonerated of all charges. She now works as a restaurant server (“Teacher acquitted”). Schoolchildren in the UK have found a way to spread baseless rumors on Tiktok that their teachers are pedophiles, causing them to quit in fear for their safety; one teacher said a malicious Tiktok post about him had 12,000 views (Bryan; Rogers). Not that this couldn’t happen in the U.S., it just may not yet have been reported. One story recently reported was the resignation of transgender professor Allyn Walker of Old Dominion University in Virginia, due to threats against his life over the publication of A Long, Dark Shadow: Minor-Attracted People and Their Pursuit of Dignity (U of California Press, 2021), a sociological study geared to understand “what coping mechanisms and mental health strategies” are used by people who feel inclined toward minors and don’t act on it, and “to help prevent others who feel the same attractions from abusing children.” His use of the term “minor-attracted people” led to the malicious assumption, fanned by rightwing Fox News host Tucker Carlson, that Walker himself was a pedophile (McDade).

The latter affair is—or should be—particularly alarming for authors, academics, anyone with a role in public commentary. We seem to be entering a new era of intolerance turned fanaticism, where the mere mention of the topic of pedophilia, however one problematizes it, draws suspicion upon oneself. Perhaps I too need to reiterate for the record that in condemning the U.S. sexual persecution regime, I am not even remotely condoning adult sexual activity with those under the age of consent. But my purpose here nonetheless may require some fresh imagination on the part of the reader.

To many, the sexual abuse of minors is a special category of depravity, the worst of crimes committed by the lowest of the low, who by their incomprehensible action void their place in society and deserve the heaviest possible punishment capable of being inflicted. But righteousness blinds us to the larger view and a more comprehensive understanding of real injustice. To put it another way, since sex crime against children is framed in terms of absolutes, it’s hard to get outside of the frame. My overriding interest here concerns the human rights violations of an aggressive state apparatus testing out the waters of full-blown fascism. The place to look for these violations in a fascist state is the scapegoated. In the U.S., the traditionally scapegoated are Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities, but the country is increasingly torn against itself on the racism issue. Public rage is shapeshifting and ever on the lookout for new, uncontroversial enemies to rally against. The sex offender fits the bill. By his unspeakable, alien acts, he gives license to both the public and the state to coordinate the unleashing of their rage upon him, with no limit to this rage. Short of capital punishment for sex offenses, the state’s power to enforce justice is always seen as not enough. The community must step in to finish the job. Convicted sex offenders are caught between these pincers. The worse the offense, the greater the carceral retribution; the lesser the offense, the greater the community retribution.

It’s commonly assumed, among those not fully apprised of the facts, that pedophiles need removal from society because they are incorrigible and will re-offend again unless locked up for good. The opposite is actually the case: convicted sex offenders have among the lowest rates of recidivism. If this comes as a surprise, you are encouraged to consult the experts on this question, starting with a comprehensive report by the Human Rights Watch (No Easy Answers). You need not fear the worst in any case. Those imprisoned for violent sex crimes against children (Tier 3 offenders in the national registry) tend to be safely put away for a very long time. Upon completion of their sentence, they are then disappeared for good, to live out the remainder of their life in a shadow network of “civil commitment” prisons that operate without public oversight or accountability, in reported conditions of “guard brutality, solitary confinement, overcrowding, rotten food, negligent medical care, broken toilets” (Levine & Meiners). Meanwhile, sex offenders who do time are not spared the public wrath just because they’re secure behind bars; they experience it the moment they encounter their fellow inmates, the public’s surrogate. Any child sex conviction consigns them to the bottom of the hierarchy, where they are ostracized and targeted for the bulk of prisoner-upon-prisoner beatings and rape.

Barbaric in its exceptionalism, the U.S. is the only country that banishes sex offenders from the community after serving their sentences.

Bleak and harrowing as the prison experience is for sex offenders, they are not released on the understanding that they have “done their time.” The United States has already one of the worst recidivism rates in the world: spat out into an unreceptive social void, parolees struggle to find employers willing to hire them, and consequently return to crime to get by—and back to prison. They are the ordinary criminals who have served their time. Sex offenders who have served their time, by contrast, are released not into a vacuum of anomie but a cauldron of hostility. The message confronting the lepers is stark and aggressive: you are not wanted back. Those who avoided prison altogether and are merely on probation have it just as bad, if not worse, as they are presumed to have gotten off scot-free. Now it’s the community’s turn to take over the reins of punishment, armed with a tool provided by the state honed for this exact purpose. The sex offender registry is no mere list, a resource that neighbors can consult to guard themselves against dangerous ex-felons coming after their kids. It’s a mechanism of the sort normally provided to secret police for flushing undesirables out from hiding. Those on the registry who have been zoned out of their communities altogether have it better in one sense. Being homeless or nomadic and banding together, they are not as easily subject to attacks by vigilantes.

The sex offender registry is not a rational solution to a social problem but a legalistic abomination whose practical effect is to demoralize ex-offenders to the point of giving up entirely. Left without means of subsistence, many return to crime in order to survive. Some may try to get back at society by going after children, precisely what their punishment was supposed to prevent. The police too have been among the most vocal critics of the registry, if for no other reason than it’s a burden on their time with all the paperwork required to keep tabs on those registered in their jurisdictions.

It may be instructive to look at how the rest of the world handles sex offenders. Many countries, including Australia, Indonesia, Russia, South Korea, and the United States, chemically castrate the most intractable — those who readily admit their predilection and who may even cooperate with the authorities in treating it (Cochrane). Only a handful of countries have a sex offender registry, and they are, interestingly, mostly English-speaking: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, South Africa, the UK, and Israel. All of them share a key difference from the U.S. version, however: the information on the registry is not available to the public but only to the police, and where the community is informed, they may not hinder the right of ex-offenders to get on with their lives. Barbaric in its exceptionalism, the U.S. is the only country that banishes sex offenders from the community after serving their sentences, either by geographically zoning them out or allowing the community to drive them out, even take revenge on them with virtual impunity (Levine; No Easy Answers).

When it comes to sex, the U.S. stands apart. As Roger Lancaster in Sex Panic and the Punitive State puts it, “Americans make sex a key criterion of their moral hierarchy with a zeal that is not equaled in any other industrialized democracy.” No other criminal offense unleashes the collective rage as the sex offense. American culture’s unique hostility toward the sex offender has its roots in Anglo-American Puritanism and finds contemporary expression in perpetual national anxiety over the specter of the “imperiled child” (Lauren Berlant, cited in Lancaster). It’s too early to assess the #MeToo movement’s impact on sexual mores and codes of conduct. The outing or shaming of people in authority who have exploited those under them for sexual gain is laudable. But rewriting ever broader forms of sexual misbehavior into law — termed “carceral feminism” by Elizabeth Bernstein — only gives greater discretionary power to the courts and the police to expand the population of offenders beyond its already staggering scope. In a snowball effect, the public clamors for greater vigilance and ruthlessness against the sex offender, politicians and judges are elected on platforms promising just that, and the prison-industrial complex, in turn, feeds on increased funding and sanction to apply their powers with greater indiscriminateness to the population at large. If the purpose of sex laws and the sex offender registry is to make the consequences so terrible that no sane person would dare encroach upon the law, the result is a society living in fear of itself.

If the purpose of sex laws is to make the consequences so terrible that no sane person would dare encroach upon the law, the result is a society living in fear of itself.

I suspect that most people — educated, civilized people — could hardly care less about the fate of convicted sex offenders. As the reasoning goes, they only got what they deserved. They constitute a small enough slice of the population to be of little concern to the rest of us. Their punishment, though harsh, sends a signal to the law-abiding majority to stay clear of this most volatile of society’s hazard zones. If their example succeeds in keeping such offenses in check, then it is of practical consequence. In any case, our sympathies should lie with the victims of sexual abuse and assault, not the perpetrators.

I have a different angle on this. Persecution of hated groups is one of the defining features of fascism. Once underway, oppression’s tendency is to deepen, multiply, and encroach on ever-larger segments of the population. It is not an inevitable but a dynamic, reinforcing process, requiring the cooperation of the state and the masses. Even the most dictatorial or tyrannical of regimes seek some legitimacy in popular support to justify their policies. Fascist regimes tap into the social and economic discontent caused by these very regimes to focus and direct popular rage at scapegoated groups through crude nationalist or racist demagoguery. By doing so, they lift the bar of state power and enlarge the parameters of control over the entire population.

It doesn’t just stop at one group, such as Hitler’s persecution of the Jews; the Nazis also singled out Communists, gypsies, homosexuals, and the disabled. The more categories of the despised there are the better: they allow the dominant group to define itself against them and feel good about itself, which shores up more popular support for the state. The state in turn gives surrogate expression to the public’s inchoate rage and renders this discourse articulate and eloquent. As the public increasingly relies on the state to explain reality, people are dumbed down in the process and made more susceptible to brainwashing. They do the state’s bidding in channeling back this articulated rage toward the hated groups. Sexual persecution is becoming as American as apple pie.

WORKS CITED

Aviv, Rachel. “The science of sex abuse. Is it right to imprison people for heinous crimes they have not yet committed?” The New Yorker 14 Jan. 2013.

Banks, Gabrielle. “Many surprised at sentence for ex-Baylor doctor who raped a Houston hospital patient.” Houston Chronicle, 17 Aug. 2018.

Banks, Russell. Lost Memory of Skin. Ecco, 2011.

Bernstein, Elizabeth. Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of Freedom. U of Chicago, 2019.

Bryan, Nicola. “TikTok school abuse: Teachers quitting over paedophile slurs.” BBC News, 23 Nov. 2021.

Cochrane, Joe. “Indonesia approves castration for sex offenders who prey on children.” The New York Times, 25 May 2016.

Cramer, Maria. “At 18, he had consensual gay sex. Montana wants him to stay a registered offender.” The New York Times, 15 May 2021.

Faraj, Jabril. “Former sex offenders left out in the cold by city residency restrictions.” Urban Milwaukee, 15 Dec. 2015.

Farley, Lara Geer. “The Adam Walsh Act: The scarlet letter of the twenty-first century.” Washburn Law Journal (Winter, 2008).

Halperin, David M. and Trevor Hoppe (eds.). The War on Sex. Duke UP, 2017.

Hess, Corrinne. “Communities continue to rethink sex offender residency rules.” Wisconsin Public Radio, 28 Jan. 2019.

Horesh, Theo. The Fascism This Time and the Global Future of Democracy. Cosmopolis Press, 2020.

Lancaster, Roger N. Sex Panic and the Punitive State. U California Press, 2011).

Levine, Judith. “Sympathy for the devil: Why progressives haven’t helped the sex offender, why they should, and how they can.” The War on Sex, edited by David M. Halperin and Trevor Hoppe. Duke UP, 2017.

Levine, Judith, and Erica R. Meiners. The Feminist and the Sex Offender: Confronting Sexual Harm, Ending State Violence. Verso Books, 2020.

McDade, Aaron. “Author says outcry over book on preventing sex abuse partly linked to their trans identity.” Newsweek, 24 Nov. 2021.

McKay, Michael. “How many kids are on the sex offender registry?” National Association for Rational Sex Offense Laws, 12 June 2018. https://narsol.org/2018/06/how-many-kids-are-on-the-sex-offender-registry/

Nir, Sarah Maslin. “A 7-year-old was accused of rape. Is arresting him the answer?” The New York Times, 3 June 2021.

No Easy Answers: Sex Offender Laws in the U.S. Human Rights Watch. Sept. 2007. http://hrw.org/reports/2007/us0907/us0907web.pdf.

Rogers, Tom. “My own pupils targeted me in the TikTok paedophile craze—now I can’t go back to our school.” The Telegraph, 23 Nov. 2021.

Stillman, Sarah. “The list. When juveniles are found guilty of sexual misconduct, the sex-offender registry can be a life sentence.” The New Yorker, 14 Mar. 2016.

“Teacher acquitted of having sex with student finds work as a waitress.” Inside Edition, 28 Sept. 2018.

Winerip, Michael. “Convicted of sex crimes, but with no victims.” The New York Times, 26 Aug. 2020.

* * *

This essay will appear in Sexual Fascism: Essays (forthcoming, January 2022)

Related posts by Isham Cook:

Transgressions: From porn to polyamory

The sewage system, or What is fascism?

Toilet terror

American massage

American fascism: The sexual rage of the state

Sexual surveillance in the Covid-19 era

June 26, 2021

Toilet terror

Utopian considerations

The performing of ablutionary activities openly in a shared social space was the norm before the individual’s right to seclusion became something sacrosanct and inviolable. People used to bathe and go to the toilet, in other words, in front of each other freely and unselfconsciously. In our day and age, however, the right to bodily privacy is so thoroughly ingrained and taken for granted it’s inconceivable why anyone would ever question it. Only in exceptional, disciplinary institutionalized settings — the army, the prison — is this right taken away. Yet it’s a relatively modern right, one that grew out of bourgeois “separate-spheres ideology” and Victorian preoccupations with the sanctity of the female sex only over the last century and a half or so. It’s also an outmoded right, despite being clung to so tenaciously, as Mary Anne Case writes: “Separate public toilets are one of the last remnants of the segregated life of separate spheres for men and women in this country, now that the rules of etiquette no longer demand that the women leave the men to their brandy and cigars after dinner in polite company.”

Well, to be more precise, the bodily right to privacy developed in tandem with late nineteenth-century technology — that of private plumbing, enabling at first the wealthy, and decades later most private residences to be outfitted with their own bathroom, although as Alexander Kira reminds us in his classic book, The Bathroom, private bathtubs designed for two could be found among the European gentry as far back as the seventeenth century. Nonetheless, privacy fetishization among the sexes remains very much alive today and is dramatically on display whenever the ladies get up on cue to go do their ritual restroom thing.

I am sorry to have to turn all this on its head in what follows, but it’s about time we disburden ourselves of the privacy fetish. This admittedly requires a drastic shift in cultural attitudes. As radical as it sounds, toilet liberation is wholly practical economically speaking and would be easily implemented, if not now then over a generation or two, as younger people already enlightened and versed in ecological imperatives take over the reins of government.

There are already signs among scattered visionaries of a relaxing of these strictures and regimes. One household fashion trend, among those anyway who can afford to tear down walls in their home or uproot their plumbing, is the “open-concept bathroom,” a large bathtub or jacuzzi as the centerpiece of a spacious bathroom or even the living room, the bather or bathers visible to family or friends. More exclusive hotels offer something comparable though the rationale is different, ostensibly being, of course, to enable you to watch TV while you bathe (or keep an eye on the fast company hoping to rifle through your pants), rather than to lure exhibitionist guests. More commonly, open bathtubs in hotels sit in a standard bathroom behind a clear glass wall, with a shade or curtain to accommodate the shy. An attractive selling point in hotels and new homes, the beautiful bathroom meant for more than one perhaps never really went away, at least in Europe. One such exquisite specimen and its wine-drinking naked couple is featured in the marvelous Hungarian film The Piano Player (1999, dir. Schübel), set in Nazi-occupied Budapest.

A bolder proposal, which I will elaborate shortly, would eliminate private toilets and bathrooms altogether and in their place encourage communal living arrangements with shared baths, showers and toilets. Anyone who has ever stayed in a no-frills dormitory or cheap hotel or hostel has experienced the shared hallway bathroom. While an annoyance if you’re not used to it, it is quickly accommodated to with revised expectations and a little mental agility. People with special bathing needs — the elderly, infirm and disabled — would especially benefit in a communal household, as they are in close proximity to people watching over them.

A hotel in Changsha, China.

A hotel in Changsha, China.The public restroom is equally deserving of beauty, elegance, even grandness, but not as a mere cosmetic gesture. A garish example is an entire temple-like WC at the White Temple complex in Chiang Rai, Thailand. The hugely popular haunt got some bad publicity years ago over an ill-advised decision to open up a separate WC exclusively for Chinese tourists, some of whom had been observed trashing the “Golden Toilet” with their messy toilet habits. The decision was reversed, and the majority of the tourists remain Chinese. The Golden Toilet has two entrances each for both sexes, visible below at the left and the right. The interior is rather prosaic, with nice décor touches but nothing in the way of a creative use of space; the upper floor is presumably for offices. Mere ornamentation slapped onto a conventional structure is in fact a waste of space. A true restroom design aesthetic would expand outward, organically, from the urinal. This makes more sense when you understand that the urinal itself is an object of beauty, with its perfect fusion of form and function. The public restroom should follow from that.

The Golden Toilet at the White Temple, Chiang Rai, Thailand.

The Golden Toilet at the White Temple, Chiang Rai, Thailand. Functionalism implies ease of access and use, but it must also be informed by utilitarianism and egalitarianism: something functions well because it’s easily used and equally accessible to all. But actually existing public restrooms just about everywhere remain a strange agglomeration of culturally imposed sexism and puritanism. In one highly representative UK study, women spend on average thirty-four times longer queuing for the toilet than men. If as a man you’ve always wondered why this is the case, imagine how your access to the men’s room would be impacted with the urinals removed. Even still, it’s easier for you to urinate in a stall by simply unzipping and peeing all over the toilet seat, whereas women often have to fiddle with layers of clothing, when they don’t have to clean up after you, if it happens to be a unisex toilet.

Men’s urinals in the Golden Toilet.

Men’s urinals in the Golden Toilet.One solution is the female urinal. I can’t think of a more eminent solution to an intractable problem which at the same time throws up more flak of resistance, and this merits some discussion. Germany has been at the forefront of this, indeed has been experimenting with female urinals in public restrooms since the nineteenth century (“Female Urinal,” Wikipedia). The rationale is not only to give women equal ease of access but to save water; women waste three times as much toilet water as men in the multiple flushing required to clean and make clean contact with toilet seats. To use a female urinal (or urinals adapted for both sexes), a woman must either face the wall or forward, depending on the urinal’s design. The urinals pictured in the gorgeous women’s restroom below are evidently intended to be used facing forward. In either case, she must pull down her pants and pull aside her panties, legs astride in a semi-squatting stance, thus exposing her groin from the front or rear for the duration of her business, though she might drape her nakedness with a dress. Or if facing the wall, the use of a handheld device such as the Pee Easy funnel would make it possible to keep her buttocks covered like men, but she would need to carry such a device around with her and be comfortable using it.

In Germany as well, some cities are converting gender-segregated WCs to gender-neutral WCs, with the ultimate goal of replacing men’s urinals with gender-neutral urinals. What the etiquette would look like in a unisex restroom with women using the same urinals as men is anyone’s guess. It’s already delicate enough in men’s urinals. There are unspoken rules, namely 1) you are not allowed to use a urinal next to another user if other urinals are available, and 2) you are not allowed to look, however momentarily, at another man’s penis. There is a third curious injunction, unconsciously observed: you are expected to acknowledge others present with subtle signs, such as adjusting your posture when a newcomer arrives or a partial glance in their direction without eye contact. This is to mutually acknowledge the boundaries; not to do so might suggest you’re intending to subvert the boundaries with perverted designs.

Obviously, the presence of women would complicate this etiquette, as female users would invariably have to compromise themselves in front of the men milling about. Even when outfitted with emergency alarms and a divider separating male and female users (among other ameliorating measures), I suppose most women, initially at any rate, would regard unisex urinals as beyond the pale and refuse to use them. Even many men might be intimidated from entering such a restroom. Ruth Barcan is acutely aware of the fear and resistance that would need to be overcome before coed public toilets could be socially accepted and implemented: “For just as the spatial separation of men and women into different rooms aims…to reduce male violence against women, so the free circulation of sound is part of women’s defenses against that same threat of violence. Knowing that your screams can be heard outside was the first thing matter-of-factly mentioned to me by a woman when I asked some of my friends whether they thought sound was an important factor in public toilet design.” The irony is that coed public toilets are the best solution to male violence, since the presence of men would presumably protect women from any violent males.

Why, ultimately, are public toilets segregated in the first place? This historically burdened question confronts us with the uncomfortable realization that the public segregation of the sexes reinforces and justifies its own unfortunate consequences. As Gershenson (citing Wasserstrom) puts it, “Sex-segregated bathrooms…are just ‘one small part of that scheme of sex-role differentiation which uses the mystery of sexual anatomy, among other things, to maintain the primacy of heterosexual sexual attraction central to that version of the patriarchal system of power relationships we have today.’ The same patriarchal system that envisions sex as a crucial binary category insists on the sexual segregation of bathrooms.”

There hasn’t been much news about these German restroom innovations since a flurry of articles appeared in the scandalized international press in 2017. Were the proposals stopped dead in their tracks after massive public resistance? Or perhaps subsequent developments have slipped under the radar? Germany is a country known for its healthy tolerance and respect for public nudity, as shocked visitors discover when they stumble upon topless pool-side bathers in their hotel and full-blown nudist parks in city centers, such as the Englischer Garten in Munich. There may indeed be adequate public support among locals for unisex WCs with unisex urinals, but municipalities are likely constrained by their growing population of conservative communities, predominantly Muslim immigrants, not to mention the many tourists unacquainted with liberal German attitudes. Any viable changes would need to be two-pronged and incremental: gradually outfitting women’s WCs with female-adapted urinals, and gradually merging or replacing segregated WCs with unisex WCs, all the while keeping enough gender-segregated WCs operating to provide people with a choice. Germans regularly go naked among strangers in coed saunas, and over time, one assumes, male leering and harassment of female users would likewise dwindle as coed toilet use became commonplace and the norm. Then if enough women could be recruited, unisex WCs could all be outfitted with unisex urinals. I would add that this would also solve at one go the problem of safe toilets for trans people.

Female urinals, unknown location, Germany (Prince Grobhelm – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3003594).

Female urinals, unknown location, Germany (Prince Grobhelm – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3003594).Germany presents us with an instructive test case on the limits of the progressive imagination. By prudish American standards, the Germans really are quite reasonable people and beckon toward what is possible. We might place Germany at one end of a continuum representing degrees of tolerance for bodily freedom, America in the middle, and more hidebound societies at the other end, such as those that regard women as inherently dirty (e.g., the practice in Nepal and Ethiopia of forcing menstruating women into huts) or as unassailably pure and needing protection and isolation, which amounts to the same thing. Far from being inconceivable or intolerable, unisex urinals and WCs do exist and are being implemented or in the planning stages by municipal governments not only in Germany but elsewhere, though still mainly confined to Europe. The reason for this growing shift toward sexual equality in public toilets, however slow and scattershot on a global scale is, again, the sheer logic of it. Above all, it’s environmentally and ecologically sound policy. Converting segregated WCs into unisex WCs saves money and space, and widespread adoption of the female urinal saves water — at a time when water shortages are becoming an urgent issue worldwide. And, of course, unisex facilities provide women the same ease and speed of use as men.

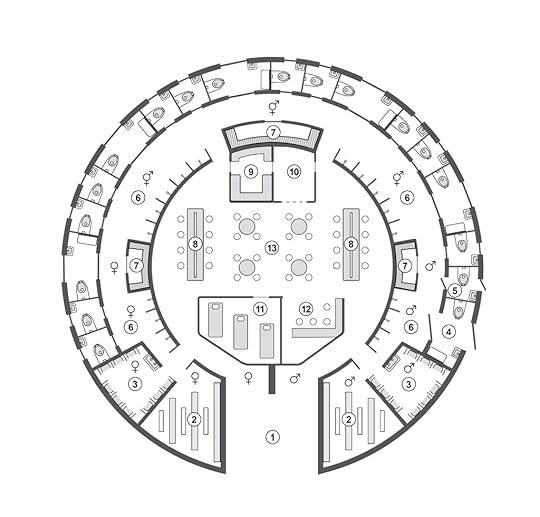

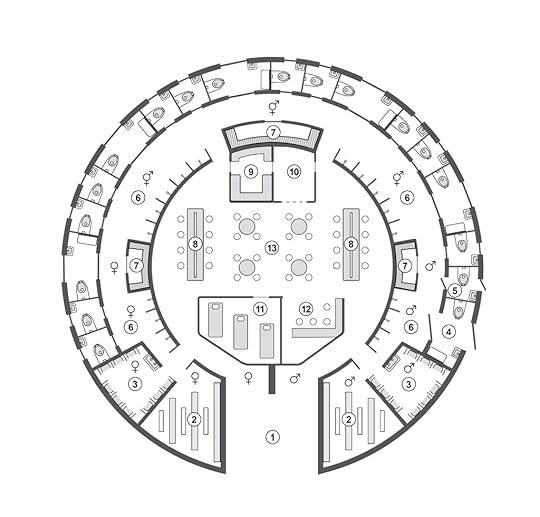

Egalitarian public restroom design (as opposed to its successful implementation) has a long history and I can hardly claim to be proposing something original, having relied on insights culled from the experts, notably Alexander Kira’s The Bathroom (Rev. Ed., Viking, 1976), and Harvey Molotch and Laura Norén’s scholarly collection, Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York U Press, 2010). The following design for a grand public restroom is my own. The structure is imagined in the round, to spotlight its aesthetic and functional self-sufficiency, though I’d stress “functional” here in the more generous sense suggested by Kira to distinguish it from the “American preoccupation with compulsive ‘cleanliness,’ devoid of any enjoyment, which results in our minimal ‘functional’ bathrooms.” On the contrary, “one can find examples today of bathrooms that are treated as family rooms, private sitting rooms, libraries, offices, formal drawing rooms, art galleries, garden rooms, beauty parlors, gymnasiums, and so on.”

Large enough to stand out in the urban horizon, my grand public restroom would be readily identifiable with its telltale dome-shaped skylight or cupola, yet each would be architecturally unique. They would come in different sizes depending on population density or local demand, and there would be smaller versions with fewer amenities, scattered around the neighborhood, some consisting of no more than several toilet rooms accessed on the outside and unisex urinals on the inside. They would be free, open to all, well-maintained, clean and safe, with attendants on hand twenty-four hours in the larger restrooms. Ideally, they would be strictly unisex, but as I must ground this in our day and age, a transitional version is presented, predominantly coed but with sex-segregated sections:

Bird’s-eye view of a grand public restroom: 1 entrance, 2 changing rooms, 3 urinals, 4 large toilet rooms, 5 small toilet rooms, 6 showers, 7 saunas, 8 trough sinks, 9 lactation room, 10 attendants’ office, 11 massage room, 12 espresso bar, 13 recreational tables. Female/male symbols indicate segregated versus coed sections. Concept and design by Isham Cook.

Bird’s-eye view of a grand public restroom: 1 entrance, 2 changing rooms, 3 urinals, 4 large toilet rooms, 5 small toilet rooms, 6 showers, 7 saunas, 8 trough sinks, 9 lactation room, 10 attendants’ office, 11 massage room, 12 espresso bar, 13 recreational tables. Female/male symbols indicate segregated versus coed sections. Concept and design by Isham Cook.As in existing, conventional public restrooms, the divided entrance requires women and men to enter separately. If one just needs to urinate, there are segregated urinal rooms directly facing the first interior entrance on either side. If one needs to defecate, there are two options. First, private-use toilet rooms line the outside circumference of the structure, larger wheelchair-accessible rooms with a baby-changing table, toilet and sink, alternating with smaller rooms containing a toilet and sink. A sign on each door indicates whether the room is occupied or vacant (as in airplane cabin toilets), but with a big “O” or “V” so that the sign can be read from a distance. There is also an electronic display at the main entrance showing the occupancy of all the numbered toilets at a glance, enabling users to quickly locate a vacant toilet. Attendants would be aware of which toilets were in operation and could notify those hogging a toilet for an inordinate length of time. Likewise, if the user has a medical issue or emergency the attendant can be alerted and spoken to via intercom.

Alternatively, the same toilet rooms can be accessed within the building from the circular corridor lined with shower stalls and saunas. If a toilet is in use, its inner and outer doors are automatically locked, and become unlocked when the toilet is vacant. But one cannot access the corridor directly from the outside via the toilet rooms; only users already inside the building and making use of its facilities have access to the toilets from the inside. This enables the staff to monitor the visitors present and prevent men from entering the women’s section and vice versa (as indicated by the gender symbols in the diagram). The larger share of the shower area is coed, however. This is to give both sexes greater access to shower and sauna space and absorb spillover from the segregated sections. It’s also to accustom people to coed use and lower general resistance to the sight of naked users of the opposite sex.

Also offered are saunas, massage and lactation rooms, double-sided trough sinks with mirrors, recreational tables (with chess, checkers, Go sets), even an espresso bar. The purpose indeed is to encourage people not only to feel comfortable and at leisure, but to hang out and socialize. Other grand public restrooms might offer different options and facilities. The largest could accommodate hot and cold pools for recreational bathing, as have long existed in Japan, Korea and China. As in Germany and a few other European countries, many spa and hot spring resorts are both coed and clothing optional, so it’s not such a stretch to imagine this degree of institutionalized freedom.

If these grand public restrooms progressed to become fully coed, obviating the need for separate male and female sections, the interior could be further streamlined with a single set of urinals, showers and saunas for all genders to use freely, safely, and shame-free. Granted, the more exotic brand of European spa aside, existing public restrooms remain a long way from this vision, “a utopian vision of men and women and people of all sorts sharing toilet space and shaping social life….As the sex ratio of users changes, one gender can spill over into the facilities ordinarily over-selected by the other, while, as the need arises, managing glance in an appropriate way” (Molotch). Indeed, there is growing awareness of the need for a new approach, and piecemeal improvements are already happening in many cities and countries. And there is always constant, bustling change, often for the better, occasionally for the worse. In what follows, I would like to present two examples of change in two countries, one exhibiting dramatic change for the better, the other dramatic change for the worse.

The Chinese Experience

When I first arrived in China in the early 1990s, toilets were so squalid it was hard to believe that a country could be so wanting in public sanitation. A telling instance was a lunch stop in one mountain tourist town famous for its sprawling Buddhist temples. We chose the most promising among a shanty-like strip of private restaurants, all lacking a restroom. I was directed around back to the public WC, if you could call it that. It consisted of an open pit of raw sewage with a rickety wooden plank laid across to squat on while defecating. The pit was set back from the street but unsheltered and its occupants fully visible to passersby. Throughout my naked squatting ordeal, a male colleague I was traveling with stood nearby and stared, out of protective concern but probably also impatience. This had a most inhibiting effect. I gave up and resolved to hold in “the uneasy load,” as Gulliver described being denied use of a privy by his Lilliputian hosts. Nervously gathering up my belongings, I managed to drop my camera into the excremental sludge and fished it out with my fingers. Back at the restaurant, there was no sink or even soap, and I had to make do with a pan of water to restore my hands and the camera as best I could. I’m not sure how they washed their dishes.

In the nation’s capital, standard public WCs of the time weren’t all that much better: dark, dirty cinderblock cells with two facing rows of squatting holes. Low dividers partially separated you from adjacent users but not from those sitting opposite; some WCs lacked dividers altogether. Clearly, this was a more “social” culture, where people felt less awkward about the communal witnessing of all aspects of daily life including the bodily functions, where the concept of individual privacy was less refined than in the “civilized” West. I had no choice but to get used to being stared at shitting by curious males whiling away the time with their cigarettes, newspapers and chitchat, sometimes quite overtly about me, naturally assuming I had arrived in the country that very day and couldn’t speak the language (after decades here some still call out to me on the street, “Welcome to China!”). If you were out for the evening you could always use the restaurant toilet, if again it actually had one, and you didn’t mind soiling your shoes in the inevitable puddles of urine, spit, cigarette butts and stray feces surrounding the squat receptacle. So extravagant were these examples of national performance art that they have attracted comment. As did David Sedaris on a trip to China in 2011 and as Arthur Meursault wickedly satirized in his novel, Party Members (Camphor Press, 2016), I found these public potty displays, for want of a better word, funny.

Men’s public WC in a Beijing hutong, 2021 (photo by Isham Cook).

Men’s public WC in a Beijing hutong, 2021 (photo by Isham Cook).Once the country opened up in earnest to foreign tourism and the Chinese themselves started travelling internationally, they became educated on the sanitary standards commonly found outside the Middle Kingdom. They became in fact acutely conscious and embarrassed about their public WC problem, so much so that the Government trumpeted the country’s urgent toilet development plans, citing such mottoes as “You can judge a nation’s civilization by the quality of its public toilets.” And they indeed worked hard on this. Over the past decade there has been a sea change, though you can still find remnants of the past alongside signs of progress. Many tiny public WCs in Beijing’s old lanes (hutong), in order to maximize their limited space, maintain squatting toilets next to each other without dividers. But these WCs are kept spotlessly clean throughout the day. Some WCs even provide toilet paper from a single dispenser in the entrance (locals are long accustomed to carrying their own). Instead of aiming their waste into the obscure sewage holes of yore, users now position themselves on the polished metal platforms and simply stamp the flusher with their heel. It’s not so bad. Look at it this way: if you’re so close together you’re knocking knees with your neighbor, you can use each other’s legs as support. And in case you haven’t been following the latest health news, squatting toilets are better than sitting toilets for evacuating the body’s waste.

These national measures are continuously being ramped up throughout the country. I was walking through a nondescript neighborhood in the third-tier city of Changchun not long ago and stopped in a public WC. In years past, it would have been a ghastly sight. The individual toilet stalls had locking doors and were spic and span — and free. Chinese school lavatories too are kept cleaner than before, although their unshaded windows still give facing classrooms a clear sightline into the male urinals. In the newer shopping malls, the restrooms are ever larger, nicer and gender friendlier. In Beijing’s China World Mall shopping plaza, for example, ample restrooms are conveniently at hand wherever you turn. One male restroom has eight toilet stalls (with a choice of squatting and sitting toilets) and ten urinals; the female restroom facing it has twelve toilet stalls, somewhat making up for the lack of female urinals.

One troublesome aspect of public toilet use in China is that, unlike the U.S., there is no law requiring food establishments to provide a restroom. Most restaurants do as a matter of course, and no bar would be foolish enough not to, but cafés generally don’t. The waitstaff will always point you to the nearest WC in the mall or down the street, or they arrange with a neighboring restaurant to let you use their restroom. But even in posh residential complexes like The Place in Beijing with its $3,000 per month rental apartments catering to foreigners, the commercial space at ground level wasn’t designed to have restroom plumbing, and few of the many fine food and coffee establishments lining the concourse have their own restrooms. From certain locations one has to walk the equivalent of a football field to get to the nearest public WC. On the other hand, restaurants, office buildings, and hotel lobbies never object to anyone slipping in to use the restroom, patron or not. Meanwhile in American cities, restaurants and businesses commonly display a sign in their window prohibiting their restrooms to non-paying customers. You seldom encounter the same in restaurants in China. Staff tend to be relaxed and not inclined to interfere. Ironically, there is a greater need for non-patron use of restaurant restrooms in the U.S., since there are comparatively fewer public WCs. This brings us to our next country.

The American experience

As with many features of American life, amenities and facilities are distributed up the socio-economic scale. You have to pay for the convenience. I don’t mean the token fee commonly charged in public WCs in Europe. You’re expected to patronize an establishment before being granted use of the restroom, whatever cost that entails. Shopping malls do provide restrooms for public use, but then it’s assumed you’re there to shop, and unkempt, indigent types may be approached by guards and escorted out. McDonald’s and other fast-food chains present an interesting exception. They are often hangouts for the massive homeless population in many cities, who are generally allowed to stay as long as they purchase a coffee; apparently you can still get one for a dollar. Some shops may look the other way even if you don’t buy anything. For all the criticism they receive for their unhealthful food and low pay, in functioning as daytime shelters for the poor, the fast-food chains perform a valuable and needed public service.

The relative scarcity of clean, safe, accessible public toilets in the U.S., as compared to other countries, has long attracted frustrated commentary by visiting foreigners and domestic sociologists, if not by untraveled Americans who have no basis for comparison and don’t know anything else, though everyone is acutely aware of the inconvenience of being stuck somewhere with a bursting bladder or bowels and no idea where the nearest toilet is. But the assumption is you have only yourself to blame, in not planning ahead and taking better precautions, in not leaving that bar, party, sports event or outdoor concert before giving yourself enough time to fully clear your bladder, and not once, if it’s a long way home or there’s a long drive or heavy traffic ahead, but twice. Or don’t drink so much. Or carry an empty plastic bottle in your car if you have to. Or find some bushes or dark corner in a park to relieve yourself in.

By this point in my essay you may be assuming my title refers merely to the nuisance of being caught in public with no WC in sight. I don’t mean to trivialize the word, but it does have metaphorical scope to encompass the relatively little things in life that bother or “terrorize” us, the many minor hassles we blow out of proportion in order to characterize a fleeting yet momentarily excruciating situation or event, which of course bears no relation to a real act of terrorism — a shooting, a bombing — or other life-threatening cataclysm. But this is actually not what I am getting at by the “toilet terrorism” of my title. What I lay out as follows refers rather to something, if not quite life-threatening, far worse than our desperate search for a toilet. By an order of magnitude worse. And it is unique to the USA.

We can start by recognizing that there is an etiquette to public toilet use, but this etiquette is not confined to the toilet itself — and this may be counterintuitive — but extends beyond the facility to encompass all urban space, indeed the entire town, suburb or city. You can get into trouble by using a toilet stall against the rules, when for example dealing or shooting drugs or having sex in one (that’s what that half-inch gap between the door and the hinge is for), or even inadvertently, when stumbling into a poorly marked entrance for the wrong sex. You can also get into trouble for not using a public toilet. Public urination constitutes the greatest violation because it’s interpreted as the most flagrant, ultimate rejection of something society, at least American society, upholds to the absolute strictest of standards — toilet etiquette. This becomes apparent when these standards are violated. In the U.S., as Kira notes, “privacy demands and sex segregation are strictly enforced by both legal and social sanctions and…casual public elimination can lead to swift arrest.” As “technologies of division and separation,” public toilets, adds Barcan, are a “form of segregation…at once immensely naturalized and immensely policed, the most taken-for-granted social categorization and the most fiercely regulated.”

Most countries have penalties for public urination, typically fines of several hundred USD, though in some locations such as Singapore the fines can go up to several thousand dollars for blatant acts like public defecation. In Germany, on the other hand, there is no law against public urination. Indeed, the law in most countries is rarely enforced unless the act is deemed flagrant enough and performed openly in broad daylight. In China, where I’ve lived for decades, I’ve never heard of anyone getting into trouble for public peeing, nor have been warned about it. In civilized Japan, salarymen can be seen urinating outside without discretion, but then again they’re dragooned into enforced after-hours drinking sessions with the boss; they’re seen throwing up on the sidewalk or in the subway station as well. It is also generally grasped that some people afflicted by age, diabetes or various colon conditions are incontinent and may have to let go in an inopportune spot before they make it home, and allowance (one hopes) is made for medical reasons. But as for young partiers who have no such excuse, is it really necessary to slap them with a $500 fine (on top of a possible ninety days in jail) if they make at least a minimal effort to relieve themselves out of sight, such as in an alley or behind a tree?

The harsh truth is that the land of the free has little tolerance for public urination. This has led to gross distortions of the law, to an extent poorly understood by the very public that’s so ruthless in fingering offenders. Public urination signifies no mere rude display but is readily identified in the American psyche with extreme depravity: obscenity and pedophilia. Whereas the law is wise enough to make a distinction between public urination or disorderly conduct on the one hand, and public lewdness or indecent exposure on the other, not all people do. That includes the police, who are at complete liberty to interpret an act of public urination as lewd or obscene. The police are expected to uphold the law, but when it comes to sexual offenses real or imaginary, they have wide latitude to do whatever they want. They also have quotas to fulfill and incentive to err on the side of severity. As everyone who reads the news knows, American law enforcement have a habit of drastically over-extending their reach, when for example they shoot innocent but suspicious-looking African Americans. But while the public is turning against racist police brutality, nabbing sex offenders has the public’s unbridled support.

Sane, reasonable people, people with a solid grounding in reality, can surely grasp that while public urination occurs and can be a nuisance, the number of those urinate for the purpose of exposing themselves is certainly miniscule. Public paranoia, by contrast, is vast and volatile.

A sobering way to gauge the frequency with which public urinators are charged with public lewdness is a Google search of “public urination laws by state,” where a host of law firms offering their services to bewildered defendants lead the search results. These sites explain patiently and methodically what is happening and what you should and should not do to avoid worsening the quicksand you are in. For what you may not realize is that time is fast working against you, and an experienced attorney is needed to negotiate with the prosecutor and the police and prepare evidence before things proceed to sentencing. U.S. states have almost unlimited scope to apply the harshest punishment for the most minor of sex crimes — to avoid appearing soft on crime. In Michigan, for instance, the minimum sentence for public lewdness is one day in jail and the maximum is life in prison. In at least thirteen states, the distinction between urination and lewdness doesn’t even apply: urination automatically results in an indecent exposure charge — and possible registration as a sex offender (Human Rights Watch, 2007). Note that it’s “at least” thirteen states. The caveat is that all states can potentially charge your simple act of urination as a sex crime at the discretion of the police. Being witnessed masturbating is an automatic sex crime, and a serious one. I presume you would never have any intention of doing that in public, but men usually jiggle their penis when squeezing out their last drops, and someone happening to espy this could misconstrue it as masturbation. A citizen’s claim to have seen you in any state of exposure, even if you were taking the utmost precautions to urinate where you thought you were unobserved, could likewise result in an indecent exposure charge that escalates into a sex crime conviction. A child’s claim, and it’s all over for you.

A good lawyer and a sympathetic judge might help extricate you relatively unscathed from the quicksand, perhaps only several thousand dollars poorer from legal and court fees but saved from the sex offender registry. In the handful of countries that have sex offender registries, only the police have access to the identities of those registered, in order to monitor their whereabouts once out of prison, while allowing them to resume their lives. But sex offender registries in the U.S., in stark contrast, extend well beyond monitoring and tracking. Since the Adam Walsh Act of 2006, the national sex offender registry has been publicly accessible on the internet. This means anyone, and not just anyone but well-organized vigilante mobs who troll the registry, can locate the address of a newly registered sex offender, harass them and their family, rally the community to pelt their home with rocks and drive them out of the neighborhood, even physically attack them, all with virtual impunity. The identities of those registered as Tier 1 sex offenders (the mildest tier for minor sex crimes like public urination) are supposedly protected from public access. However, states have their own, more stringent registries which often do nothing to protect mild offenders. Worse, the registries don’t specify a person’s offenses, so you are assumed to be among the worst of the worst and are lumped together with baby rapists — for the crime of having been caught relieving yourself of a full bladder.

You are invited to read the dour Human Rights Watch report of 2007, “No easy answers: Sex offender laws in the U.S.” (things haven’t improved much in the years since), to enlighten yourself on the further consequences of being a registered sex offender in the U.S.: loss of job and potentially permanent unemployability (some states keep you on the registry for life); loss of residence as landlords (who have access to the registry) refuse to rent to you and child predator laws zone you out of your own town or city (all sex offenders are deemed a danger to children regardless of their offense), forcing you to join vagrant tribes of homeless sex offenders in scattered highway underpasses or designated rural trailer parks; and no way of paying for your accumulating court and administrative fees, GPS ankle bracelet rental fees, etc., apart from what your family is able or willing to shell out on your behalf. The U.S. is the only country in the world, by the way, to exile sex offenders, brand them irredeemable, and render them homeless and without means of subsistence.

In short, as a Men’s Health article puts it, “when you have to urinate so bad that holding it is no longer an option, you might want to consider just peeing in your pants. It may ruin the rest of your night, but the rest of your life will be spared.”

When the state multiples crime by creating new categories of crime; when it singles out groups for disproportionately punitive treatment and enlists a duped public to collaborate in the name of safety and security; when the state inventively deploys the latest technologies (comprehensive databases, GPS tracking, facial recognition) in the service of prosecuting crime; and when out of all of this emerges an atmosphere of fear designed to intimidate and terrorize the population including those supporting these measures, fear not only of the state but of one’s neighbor, fear of the racial or sexual predator, down to the fear of being caught without a toilet in public: we have arrived at fascism in its contemporary guise.

Works cited

Barcan, Ruth. “Dirty Spaces Separation, Concealment, and Shame in the Public Toilet.” In Harvey Molotch and Laura Norén (Eds.), Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York U Press, 2010).

“Berlin’s new toilets: Would you use a women’s urinal?” BBC News, August 11, 2017 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-40899902).

Case, Mary Anne. “Why Not Abolish Laws of Urinary Segregation?” In Harvey Molotch and Laura Norén (Eds.), Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York U Press, 2010).

Gershenson, Olga. “The Restroom Revolution: Unisex Toilets and Campus Politics.” In Harvey Molotch and Laura Norén (Eds.), Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York U Press, 2010).

Human Rights Watch. “No easy answers: Sex offender laws in the U.S.” September, 2007 (http://hrw.org/reports/2007/us0907/us0907web.pdf).

Kira, Alexander. The Bathroom (Rev. Ed., Viking, 1976).

Levitan, Corey, and Bettmann/Corbis, “You might be a sex offender and not even know it!” Men’s Health, May 19, 2015 (https://www.menshealth.com/trending-news/a19541024/you-might-be-sex-offender-and-not-know-it/).

Meursault, Arthur. Party Members (Camphor Press, 2016).

Molotch, Harvey. “On not making history: What NYU did with the toilet and what it means for the world.” In Harvey Molotch and Laura Norén (Eds.), Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York U Press, 2010).

“The Peequal: Will the new women’s urinal spell the end of queues for the ladies’?” The Guardian, June 7, 2021 (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jun/07/the-peequal-will-the-new-womens-urinal-spell-the-end-of-queues-for-the-ladies).

Sedaris, David. “David Sedaris: Chicken toenails, anyone?” The Guardian, July 15, 2011 (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/15/david-sedaris-chinese-food-chicken-toenails).

“Should I be worried by indecent exposure and public urination crimes?” Gravel & Associates. Michigan Sex Crimes Lawyers (https://www.michigan-sex-offense.com/public-urination.html).

“Thai temple to build separate toilets for non-Chinese visitors after complaints: report.” Straights Times, February 28, 2015 (https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/thai-temple-to-build-separate-toilets-for-non-chinese-visitors-after-complaints-report).

Wasserstrom, Richard A. “Racism, sexism, and preferential treatment: An approach to the topics,” UCLA Law Review 24 (1977): 581–615.

Yuko, Elizabeth. “The glamorous, sexist history of the women’s restroom lounge.” Bloomberg CityLab, December 3, 2018 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-12-03/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-women-s-restroom-lounge).

* * *

This essay will appear in Sexual Fascism: Essays (forthcoming, January 2022)

Related posts by Isham Cook:

The sewage system

American fascism: The sexual rage of the state

Sexual surveillance in the Covid-19 era

An American talisman

American massage

Toilet terrorism

Utopian considerations

The performing of ablutionary activities openly in a shared social space was the norm before the individual’s right to seclusion became something sacrosanct and inviolable. People used to bathe and go to the toilet, in other words, in front of each other freely and unselfconsciously. In our day and age, however, the right to bodily privacy is so thoroughly ingrained and taken for granted it’s inconceivable why anyone would ever question it. Only in exceptional, disciplinary institutionalized settings — the army, the prison — is this right taken away. Yet it’s a relatively modern right, one that grew out of bourgeois “separate-spheres ideology” and Victorian preoccupations with the sanctity of the female sex only over the last century and a half or so. It’s also an outmoded right, despite being clung to so tenaciously, as Mary Anne Case writes: “Separate public toilets are one of the last remnants of the segregated life of separate spheres for men and women in this country, now that the rules of etiquette no longer demand that the women leave the men to their brandy and cigars after dinner in polite company.”