Faith A. Colburn's Blog, page 4

September 18, 2017

Romantic Conundrum

I had the weirdest experience last week. I shared it in brief on Facebook, but I’m still thinking about it.

You see, I read someone else’s book. I won’t say whose and I won’t give the title, because what I’m about to write is a spoiler. It’s about the end. It really surprised me and I’m trying to tease out the reason it did. I realize it’s good to have a surprise at the end of a book and yet I wasn’t at all prepared for the way it turned.

I remember thinking about half-way through the book, that the online description had tricked me into reading a genre I rarely read purposely—a romance. I don’t have anything against romance, just prefer other reading material. But when you read something in a specific genre, you have specific expectations. Right? When you read a romance, you expect a happily-ever-after with the handsome prince. But that’s not how the book ended so, for a moment, I felt disappointment. Then I had to wander off into some prairie grassland and think some more.

I had to take a little hike into the grasslands.

I had to take a little hike into the grasslands.First, I compared the book I’d just read to the one I’d just published. My book is historical fiction. I consciously and emphatically labeled it historical fiction, not historical romance. There’s a romance in it, but it doesn’t follow the formula for a romance. The book I read was what I would call a contemporary woman’s journey and at the end she’s finished that part of her journey–with miles yet to go.

Given that I have a romance in my book, but don’t call it a romance, I wondered why on earth I decided the books I read was a romance. Well of course there was that drop-dead gorgeous pransome hince who’s obviously in love with our heroine. They cavort in a romantic Irish setting—far from our heroine’s normal surroundings. The prince is hard to get—damaged by his past—yet it’s love at first sight for him and he spends the entire narrative trying to win our protagonist. He may in the end. I believe this is the first in a series, but the book ends with the heroine going off to resolve her own issues.

So my unresolved questions are these: If a book has a woman and a drop-dead gorgeous man in it, must it end happily-ever-after? If a woman and a man become romantically involved in said book, must they end up together? If a woman writes a book about a woman, sets her up with a man who adores her, then sends her on another path, how do we prepare our readers for the surprise at the end? In our book description do we have to say this is not a romance?

September 8, 2017

There’s a Killer Out There!

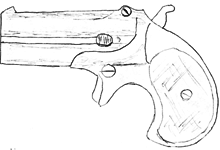

I left the apartment and scurried down the stairs. Outside, I noticed the cloudless sky and hurried to my first stop before the pavement got too hot. I’d had an idea overnight, and I stopped first at the pawn shop, two blocks away. I found a little gun that would just fit my hand. Burt, the pawnbroker, called it a woman’s gun—a derringer. But would it stop someone if he wanted to catch me? That’s what I wanted to know.

A little gun for protection.

A little gun for protection.“What do you want that for?” Burt asked.

“They still haven’t caught the Torso Murderer, and I’m coming home after dark from the Pavilion, Burt.”

“Ya, but there are a lot of people getting on and off the streetcar with you. I thought your dad was meeting you when you got off the car.”

“Well, he is, Burt, but sometimes he gets held up, and I have to wait there for a while. Besides, with his leg, I’m not sure he could protect either one of us.”

That wasn’t a lie.

“Your dad should be using the gun.”

“With his crutches?”

Burt sighed. “I’ve done a lot of business with your family, Bobbi, and I’m not in favor of this. Do you even know how to use it?”

“I was hoping you would give me a demonstration.”

“Huh,” Burt said, eyeing me. “What is going on with your dad these days?”

“Oh, you know. The crutches make him slow. He can’t find any jobs—at least until that leg heals. He’s not very happy.”

Boy was that an understatement.

“Huh,” Burt said, taking the gun from me. “This is how you open the action to load it,” he said. “See. It’s loaded.

“Shoulda checked that,” he muttered. “You close it like that and here’s the safety. Don’t flip that safety off unless you’re ready to shoot or you’ll shoot yourself in the toe.”

I gave him a half smile.

He insisted that I play with the gun for a while as he watched. “That’s it,” he said. “I’d get a box of ammunition and practice, if I were you.”

“Where?”

“I probably have something that will fit that.”

“No. Where would I practice?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“I don’t either. I guess I’ll just take my chances. Thanks for the lesson. I pulled out my wallet and paid the bill.

September 1, 2017

Eclipse

This comes a little late, I guess, but I needed a few days to process.

Since I live next to the largest railroad switch yard in the world, I wanted to get away from the roar of the railroad for the eclipse. I hoped to watch the sun disappear in a place where I could hear the response of wild creatures.

Here’s my spot. Already colors have begun to change.

Here’s my spot. Already colors have begun to change.Working with another author on formatting her book, I found time slipping away, but I finally told her I’d get back after the eclipse and rushed out the door, into the car, and headed north. About 20 miles out of North Platte, I turned off the main highway and headed east on the Garfield Table Road. After a couple of sashays onto gravel roads that didn’t quite suit me, I picked a spot and pulled off on the grassy shoulder just off the blacktop.

The sky had been darkening as I looked for my spot, but getting my camera and my eclipse glasses ready so occupied me, I couldn’t feel grateful then for my spot. In moments, I had the rear gate of my Prius open, giving me a place to sit and watch. I got my glasses on, and my camera trained on the sky. Suddenly I had time to listen and look.

At first, a thin cloud cover veiled the sun. Here’s my first shot just pointing and shooting.

At first, a thin cloud cover veiled the sun. Here’s my first shot just pointing and shooting.First, I heard the whisper of water spraying on corn and noticed a center pivot system across the road. No other sound intruded on the darkening silence. I tried a few shots with my camera set at 4000 of a second at f 3.5–the settings that would allow the least possible light. Oops! Though the sky only revealed a tiny sliver of sun, I got a blur of light.

Sun sliver against black sky.

Sun sliver against black sky.I set the camera down and waited for totality. Meanwhile, I heard little twitters like birds in the grasses settling down for the night. Across the road in the corn, I heard a few peaceful chirps—blackbirds maybe. As the air cooled, the tiniest of breezes stirred individual blades of rye grass, the only grass with blades wide enough to catch the tiny bit of moving air. The finer grasses lay still.

At last. Totality.

At last. Totality.When the moon had totally covered the sun, leaving only the fire of its corona, I left the focus set to infinity, and let the camera choose shutter speed and aperture. I got some fine corona photos. I noted, when it got as dark as it would, I heard crickets and the birds when silent. As sun began to escape the moon shadow, the only sound I heard, again, was the water whispering in the corn.

August 25, 2017

It’s Alive!

I had kind of forgotten how exciting it is to finally get a book up and running. My fourth went live on Amazon just two days ago and that’s pretty rewarding. I will write a little more about it later. Right now, I’m focused on the book I helped to format. It’s called How to Create Your Balanced Life and it’s about pretty much what the title says. Kolleen and I had been working on a final copy edit and formatting since Thursday, August 17, 2017, just four days before the eclipse.

I would make changes and send the manuscript to Kolleen. Some of the changes would disappear in transit. She would make changes and send to me and, sure enough, some of the changes would be gone. This is all by email as we’re trying to live our normal lives. Monday, time for the eclipse inched closer and closer and we were so close. Finally I said, “Kolleen, I have to go,” and I took off. (I had some driving to do to get to my spot.)

Post eclipse, (we both got to see it) we finished what we’d started. What’s cool is that Kolleen is publishing her first book and the excitement in her voice kept rising as we got closer and closer. When I sent her the final PDF, her designer hadn’t quite finished with the cover, but the end was so near she just knew she would finally get to send everything that night. Kolleen wanted to have copies for the Nebraska Writer’s Guild booth at the state fair and she had lots of hope she would make it. It’s been a marathon, but I think the publisher got all her materials on Tuesday morning.

As for me, I’ve now got my first copies of The Reluctant Canary Sings, so I will have some for the booth. Yay! I’m not sure getting those first few copies ever gets boring. It certainly hasn’t yet. A person has to kind of “rub around” on them as an old colleague of mine used to say. You’ve got to pick them up and handle them—and then wipe off the fingerprints.

Now, I’m really excited because I already have a couple of reviews and I’m looking forward to taking books to the Indie bookstores here in Nebraska and arranging for a book signing/reading tour. Set in post-Prohibition, Depression-Era Cleveland, Canary follows a young singer through about five years of singing for her supper. For more about The Reluctant Canary Sings, check out earlier installments of my blog for costumes, cars, slang, character profiles, and even an excerpt or two.

Check me out next Friday for something on the eclipse. I got to see it all alone on top of a hill in the Sandhills.

August 11, 2017

V O I C E S

I’ve just read in Discover Magazine that scientists have enough anatomical info about woolly mammoths, extinct birds and dinosaurs, and even our ancient human ancestor, Lucy, to recreate their voices. That’s amazing, but in some ways, it makes me sad.

It will be wonderful and instructive to hear all those ancient sounds, but the vocal chords I wish I could resurrect are my mother’s. Because of Mom, I grew up with music. I’ve written before about how she sang every waking moment of every day.

She said, “There’s never a moment some melody doesn’t pour through my head.”

Those melodies poured through our home, providing a lovely background to my childhood–when I wasn’t out climbing trees or carrying my sister around on my back, playing horse and rider.

I’ve also written about my mother’s career as a big band canary, but I’ve never mentioned the time I made her cry.

I was a little kid—a preschooler—and I was playing in her bedroom. I don’t think I was supposed to be there and I know I was not supposed to play with the old 78 rpm records. But I found them—the ones hidden away—and I dropped one. Predictably, it shattered.

When she found me, I don’t think my mother even paddled me. I don’t remember that she did. I do remember that she cried. I did not know until much later that the voice on the record was hers.

So I have only my own voice, my range is as broad as hers, but a little lower. And I have my memory of tunes—a lullaby she sang to me—she was Irish and I think the chorus must have been Gaelic. She sang—”Down in the meddie in an iddie biddie pool, fam three little fiddie and a mama fiddie too.” I remember songs like Somewhere Over the Rainbow and Serenade in Blue, Blues in the Night and Deep Purple. She learned new songs as they came out—often from the Lawrence Welk show on Friday nights. We watched it every week.

I just wish those paleontologists could recreate my mother’s voice. Wish I’d had the sense to record it when I had the chance.

August 4, 2017

How To Survive Day One

I did a mountain of research for the 20,000 words I dropped from The Reluctant Canary Sings. I found several autobiographies by women who served, and their accounts were so full of detail that I was able to really provide a picture of that way of life. Culture shock is an understatement for Bobbi’s arrival at Fort Des Moines, so I tried to see her first day or two through her city-bred eyes. Here’s her first day, as described by other recruits and as I imagine it from the perspective of someone who never left the city.

Imagine a city girl forming up on parade grounds this open to the sky.

Imagine a city girl forming up on parade grounds this open to the sky.Exhausted from dozing in the rattling train during the previous night, Bobbi expects to fall asleep immediately, but she finds herself listening to the silence. She hears the twenty-four women breathing around her—even some of them snoring—but no cars going by in the night, no footsteps, no people talking on the street, no dumpster lids clanging, no scuffles or shouts. She expected change, but this is a different world. She rolls over on her side and stuffs her pillow under her head, but that doesn’t feel comfortable either. After trying both sides, her back and her belly, she finally dozes, only to be awakened, seconds later, to that same blaring whistle that announced lights out. She opens her eyes to complete darkness. Before she can close them, somebody yells “Everybody up!”

“It’s still night,” she mutters and turns over. “I just got to sleep.”

“Let’s go, let’s go,” yells the voice and suddenly Bobbi sees red through her closed eyelids.

She flings her arm over her eyes as she hears the voice coming closer.

“C’mon,” says Bonnie. “Time for breakfast.”

“Breakfast? What time is it anyway?”

“Five forty-five.”

Bobbi groans. “People really get up at this hour?”

“Yup,” says Bonnie as Bobbi begins to hear other voices, muttering and groaning, and twenty-four other women scurrying into their clothes.

Bobbi throws her legs over the side of the bed, head still on the pillow. “I’m moving,” she says, mostly to herself. She sits and starts fumbling for her clothes, watching the others stumbling over footlockers and stubbing their toes on beds on their way to the showers. “Glad I showered last night,” she murmurs to herself as she pulls her suitcase from under the bed, sorts out clean underwear and gets dressed.

Using her hand mirror, she slaps on a little lipstick and stands to leave. “You ready?”

“I thought you’d be putting on a whole new face,” Bonnie comments.

Bobbi raises an eyebrow. “Do I need to?”

“Well, no,” Bonnie stammers. “I just thought . . . .”

“I had this whole ritual before I went on every night. Lay it on thick because the spotlights fade it out. Paste it back on during the breaks where the sweat washed it off . . . . Feels wonderful not to bother with all of that.”

“You look great without it.”

“Don’t know about that, but it feels better. Let’s go get food before it’s all gone.”

They’re about to step out into the aisle, between scurrying bodies, when the Third Officer steps into the doorway and yells, “Attenhut!”

Not sure what she’s supposed to do, Bobbi looks around at the others. They’ve all come to a stand-still wherever they are, so she does the same.

“Fall out!” yells the Third Officer and everybody stands watching her like a flock of nervous quail. “That means you can go now,” she says.

Bobbi hesitates a minute as they start moving. “Form up outside on the parade grounds.”

As Bobbi’s eyes adjust to the darkness, she begins to see women wandering around forming into three groups in front of the three barracks. When the officer comes to the head of her scattered column, she yells, “Attenhut!” again. The talking stops and the women stand a little straighter. When she shouts, “For’ard harch!” Bobbi thinks she sees a wicked little grin as the women start shuffling forward. Fifty yards later, when she yells, “Halt . . . Break ranks!” Bobbi looks around to see if she can spot the ranks they’re supposed to break, but all she sees is a clump. She follows a sort of line into the building.

Inside, she ends up behind Dottie and Bonnie with Shirley following. When they get through the chow line—already she’s learning a whole new language—they choose a table together. Last to get there. Shirley stumbles in her heels and catches herself with her tray on the edge of the table. Her omelet, hashed browns, bacon, and pancakes do a little flip and land close to where they started, but every beverage on the table upsets, causing five women to clamber over the benches where they were sitting as they mop orange juice, coffee, and milk off the front of their clothes.

“Sorry,” Shirley murmurs as she waits for the others to sit before she takes her place at the end of the bench, jiggling the solid table just a little bit.

This is wonderful, Bobbi thinks to herself, all I can eat and then some. She digs in and finishes everything on her plate. She knows she’s gained a few pounds since Buffalo and she knows she’ll have to be careful or she’ll really balloon, but she figures the Army will make sure she gets plenty of exercise.

Her belly full, Bobbi troops back to the barracks, chatting with the other five—Bonnie, Dottie, and Shirley, and a couple of women from straight across the aisle—Betty Schmidt from Tucson and Barbara Jean from Arkansas. Barbara Jean just wants to get out of the hills before she marries some hillbilly out of desperation, she says and Betty says she’s been a secretary in Tucson and the WAACs represents escape from boredom. Besides, it turns out she’s engaged to a soldier who’s been sent overseas and she hopes to get sent over, too. Bonnie points out that “overseas” includes most of the globe, but Betty just shrugs.

Back in the barracks, Dottie digs around in her suitcase and pulls out a bottle of nail polish to touch up the chips, but she no more than gets the lid off before Third Officer bellows, “Fall in!” from outside the barracks, sending the women scurrying down the stairs again.

The day turns into a blur very early. Sometime in the morning, Bobbi visits the Infirmary where she has both arms poked and scratched with vaccines.

In Requisition, she collects her forty-eight items of Army-issued clothing and toiletries. As the others sign out with their new wardrobe, Bobbi shuffles through her pile and clucks her tongue, holding up her baggy, khaki-colored, rayon panties and bra to match. She turns over her folded stockings in beige cotton—with garter tops.

Dottie giggles. “We’ll have to have a fashion show tonight,” she says.

Bobbi smiles to herself, noting a big contrast with the things she had to wear at her previous job.

Once they’re all outfitted, they hurry back to the barracks with their haul to change into their new duds. Nobody’s feeling much like a fashion show. Most of them give up their underwear with reluctance, setting aside their dainty, lacy. One thing about it, Bobbi thinks with satisfaction, as she squirms into her new costume, it’ll be much harder for men to get their hands inside her brown, Army-issued girdle.

After rushing around all morning, the women line up in the mess hall, holding their trays and looking reverently into plates stacked with good food. Bobbi again sighs her appreciation of the plenty, as they find a table. Shirley brings up the rear for a second time and bumps the end of the table as she sits, again sloshing beverages and causing a few moments of chaos as everyone mops up the running liquids.

“Sorry,” Shirley murmurs.

Crisis over, Bobbi digs in to roast beef, mashed potatoes, and green beans. She eats until she’s stuffed, then nibbles on a piece of rhubarb pie.

The three smaller women nibble the rest of their meals and the four leave the mess hall, thinking they will have the rest of the day to relax after playing hurry-up all morning, but they’ve no more than settled on their beds than they hear the already-familiar “Attenhut!”

Bobbi recognizes the Third Officer as she strolls in and takes a quick look around.

“My name is Lieutenant Bayer,” says the WAAC officer, “and I’m your Platoon Commander.”

She tells them they can sit, so Bobbi takes her place on the side of her bed while Bayer outlines her new rules—the first person to see an officer must call out, “Attention,” she says. Retreat’s played at the end of the working day at five o’clock and lights-out’s at nine. Bed check’s at eleven—and you’d better be there.

Sounds like kindergarten, Bobbi thinks.

When Lt. Bayer demonstrates how to pack a foot locker, Bobbi thinks about the chaos she lived in for years and smiles with satisfaction. Wow, she thinks, I’ll be able to find things. She glances around as Bayer gathers the women to demonstrate bed-making—the Army way.

“These beds should be so tight, you can bounce a quarter on them,” she says, demonstrating. They watch as she pulls the top sheet down over the blanket, then takes a ruler out of her pocket and measures six inches.

“Okay,” she says, looking around, catching each woman’s eyes, “the top edge of the top sheet to the top edge of the blanket must be exactly six inches. The cuff over the blanket must be the same—not six and one-eighth inches, not five and seven-eighth, but exactly six inches . . . both places.”

Bobbi’s thinking that might be taking neatness to an extreme when one of the other begins to protest. “But how will we . . .”

“Your toothbrush is exactly six inches long,” Bayer says as she moves to the end of the barracks and watches.

Bobbi rolls her eyes at Dottie, and tears her bed apart, but as the four—Dottie on one side, Bonnie on the other, and Shirley in the next bed—bend to the task, they keep bouncing against each other, suppressing giggles that try to bubble up their throats. When they’ve finished, Bobbi produces a quarter from the change purse she’s thrown on her foot locker and drops it on the bed. It bounces, sort of.

“Tighter,” barks Bayer strolling by in the aisle.

The women remake their beds, repack their foot lockers and stow their personal, before-the-Army belongings in their wall lockers. They hear retreat playing when they finally pass Bayer’s inspection.

When she says, “That’s fine,” the whole squad room seems to take a deep breath and sigh. “This is what your squad room should always look like in the future,” she says.

She releases them to the mess hall, and this time when Shirley sits everybody else grabs their beverages and holds them aloft until she’s seated. After stuffing themselves again, Bobbi and Bonnie decide to take a little walk, just to see the post in daylight. They pass several women’s barracks under construction, kicking up dust.

“There’s nothing here,” Bobbi says.

“What did you expect?” Bonnie asks.

“I don’t know. Something. Isn’t Des Moines a city?”

“Yes, but this is a military post. The city is . . . must be about four miles.”

“But you can’t even see it.”

Bonnie shrugs.

“It’s just flat. Everywhere I look, there’s just that empty sky and nothing.”

“Can’t you hear that rustle?”

“Yeah. What is that?”

“That’s corn stalks. See that tannish field way over there,” she says, pointing toward the edge of the post. “That field’s ready to harvest—or just about anyway.”

“So we’re in the middle of a big corn field?”

“Well, there are probably some other crops around here.”

“So that’s what a farm’s like. Just flat?”

Bonnie chuckles. “Not exactly, but a flat field’s easier to farm.”

“It’s just so empty,” Bobbi says as they head back toward the barracks.

“Not at all, Bobbi. If you know how to look, it’s just teeming with life . . . more than you can even imagine.”

“If you say so,” Bobbi says, taking the bottom step up to the squad room. “It just seems barren to me.”

Bonnie shakes her head.

~~~~~~

Bobbi’s writing a promised note to Mary Teresa when someone yells, “Attention!”

Good grief, she thinks.

Bayer leads her platoon to the back side of barracks row where they grab brooms, mops, soap, and rags. They scurry into their version of formations and march, mostly without running into each other, back to their own barracks. Bobbi tries not to giggle as she surveys the crooked ranks of women, mops over their shoulders, marching knees high and out of step, across a dusty field of rank grass.

“I want these floors to sparkle,” Bayer shouts, “hands and knees, girls.”

Without thinking, Bobbi starts humming Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.

“Who’s singing in here?” demands Lt Bayer.

Bobbi stops mid-bar. “This is gonna be a cheery place,” she mutters under her breath.

“What was that?” demands Bayer.

“Nothing . . . sir,” Bobbi says

“You will stand and salute when you address me,” says the Lieutenant.

Bobbi stands and snaps a smart salute. “Nothing, sir,” she repeats.

“That’s better,” says Bayer, suppressing a grin. “Get back to work.”

The women complete their cleaning detail at midnight and crawl into tightly-made bunks. Bobbi hears sighs all around her as the lights go out.

Boy am I out of shape. Stiff and sore after that little bit of marching around. I suppose the Army will take care of that—if it doesn’t make me too fat to move at all.

She drifts into a deep sleep. But in only a few minutes, it seems, the most piercingly awful racket she’s ever heard, jerks her into consciousness. Lights snap on, blinding her as she scrambles out of bed.

“Fire alarm,” yells Bayer. She’s standing at the barracks door, fully clothed. “Line up in formation outside.”

Twenty-five women scramble into shoes and clothes as fast as they can.

“No time to dress,” Bayer yells. “Get your asses out of here!”

In seconds the women are arranged in ragged lines, shivering in Army-issue pajamas.

“Attention!” yells Bayer, saluting.

“Holy Bejesus,” Bobbi mutters, coming to rigid attention.

“Straighten up those lines,” Bayer yells.

The women adjust their placement, continuing to stand at attention.

“All right,” Bayer says, “fall out.”

They all scatter, hustling into the barracks to grab whatever sleep they can get.

July 28, 2017

Bobbi’s Dad

Paul Bowen is the last of the major characters in this novel. A good share of Bobbi’s life story has to do with lack of stable community, so a lot of people come and go. That rootlessness characterized the Great Depression of the 1930s. People moved from place to place, as families and often as individuals, in order to make any living they could find.

Paul liked to go to the track with his friends. As a math savant, he could figure the odds and come out ahead almost all the time.

Paul liked to go to the track with his friends. As a math savant, he could figure the odds and come out ahead almost all the time.Paul Bowen suffers more complete devastation from the hard times of the 1930s than any of the other characters in this novel. He’s been accustomed to mingling with Cleveland’s movers and shakers, familiarly greeting the guests in his up-scale restaurant–until the bottom falls out of the economy. When the restaurant closes and he loses his job, he flounders from day job to day job, making a little extra at the racetrack and bearing the criticism of his wife, who fears that he’ll lose more than he wins.

Paul’s a sturdy six footer at about 180 pounds. He’s a green-eyed red-head and a flirt, which also drives his wife to distraction. An orphan raised by Catholic nuns, he tends to repress his emotions and he’s embarrassed by the shabbiness poverty forces on him. He’s always conscious of that shabbiness and constantly adjusts his clothing, particularly tucking his shirt. Although he’s a math savant, he flunked out of school and that embarrasses him, too. Sometimes his feeling of inadequacy leads him to make decisions that make his family’s condition worse.

Though he’s a born extrovert, he’s learned to be cautious around people he doesn’t know well–and there aren’t many he does know. He grumbles a lot, with occasional minor flare-ups. He withdraws from any kind of emotional loss or conflict, but embraces change because anything has to be better than his current circumstances.

He’s unable to think of a future beyond just getting by, but if he could change anything, he’d make enough to comfortably support his family. His daughter’s good opinion of him is the most important thing in his life, but he can’t believe she thinks him worthy.

Bobbi’s Dad

Paul Bowen is the last of the major characters in this novel. A good share of Bobbi’s life story has to do with lack of stable community, so a lot of people come and go. That rootlessness characterized the Great Depression of the 1930s. People moved from place to place, as families and often as individuals, in order to make any living they could find.

Paul liked to go to the track with his friends. As a math savant, he could figure the odds and come out ahead almost all the time.

Paul liked to go to the track with his friends. As a math savant, he could figure the odds and come out ahead almost all the time.Paul Bowen suffers more complete devastation from the hard times of the 1930s than any of the other characters in this novel. He’s been accustomed to mingling with Cleveland’s movers and shakers, familiarly greeting the guests in his up-scale restaurant–until the bottom falls out of the economy. When the restaurant closes and he loses his job, he flounders from day job to day job, making a little extra at the racetrack and bearing the criticism of his wife, who fears that he’ll lose more than he wins.

Paul’s a sturdy six footer at about 180 pounds. He’s a green-eyed red-head and a flirt, which also drives his wife to distraction. An orphan raised by Catholic nuns, he tends to repress his emotions and he’s embarrassed by the shabbiness poverty forces on him. He’s always conscious of that shabbiness and constantly adjusts his clothing, particularly tucking his shirt. Although he’s a math savant, he flunked out of school and that embarrasses him, too. Sometimes his feeling of inadequacy leads him to make decisions that make his family’s condition worse.

Though he’s a born extrovert, he’s learned to be cautious around people he doesn’t know well–and there aren’t many he does know. He grumbles a lot, with occasional minor flare-ups. He withdraws from any kind of emotional loss or conflict, but embraces change because anything has to be better than his current circumstances.

He’s unable to think of a future beyond just getting by, but if he could change anything, he’d make enough to comfortably support his family. His daughter’s good opinion of him is the most important thing in his life, but he can’t believe she thinks him worthy.

July 25, 2017

Fort Des Moines

When you buy a movie, sometimes you get the extended version with the out takes. What follows is one of the out takes from The Reluctant Canary Sings. At one point, I thought Bobbi Bowen would join the WAACs and I wrote some 20,000 words about her military career. This scene is her journey to boot camp, from the 20,000 words I deleted. (Well, I don’t throw anything away.)

Here’s a group of recruits marching to the trucks in daytime.

Here’s a group of recruits marching to the trucks in daytime.Three weeks later, she got orders to report to Union Station at 2814 Detroit Avenue, no later than 2:30 p.m. on Saturday, September 12. She’s in the Army now.

On the specified afternoon, Bobbi climbed into a taxi alone and stepped out a few minutes later in front of the Union Station arches, slinging her purse over her shoulder, grabbing her overnight bag in her right hand, and hauling her battered suitcase up the steps with her left. Inside the high, vaulted concourse, she walked into bedlam with soldiers, sailors, their wives and girlfriends, and a few miscellaneous civilians stuffed into the waiting area. Sound echoing off the granite concourse added decibels to the confusion.

Bobbi spotted a particularly frenzied group of women, with photographers’ flashes going off and reporters scribbling in little notebooks. When she sidled over to see what was up, she discovered the WAACs. Someone pinned a gardenia on her and a reporter started shouting questions while a photographer snapped photos.

“Hey, aren’t you Bobbi Bowen?” the reporter demanded a couple of questions into his interview.

“Yes,” Bobbi said, smiling.

“Tell me again why you joined the WAACs.”

As she started to answer, she heard the recruiter yelling into a microphone. “All WAACs over here, please.”

Boy, he doesn’t know how to use a mic. She walked away from the reporter.

After a little farewell and congratulations speech, the women hurried off to Track A. There they boarded a New York Central Pullman heading for Fort Des Moines in the middle of what looked on the map in the library like a very blank space in the middle of the country.

As she stepped aboard, Bobbi wondered how long it would be before she returned to Cleveland. She knew one thing, though, she wouldn’t have to worry about the rent or the grocery money. She would have a roof over her head and plenty to eat for the duration.

She joined the first women to board and found a window seat where she sat humming Chattanooga Choo-Choo as the rest of the women found their seats. She’d changed her wake-sleep schedule during the last couple of weeks, but felt pretty groggy, and worried the rattle of the rails would lull her to sleep.

When another recruit sat across from her, though, she reached across with her right hand, “Bobbi Bowen.”

“Dorothy Cowan. People call me Dottie,” said her new friend, taking Bobbi’s hand in a warm grasp. “Pleased to meet you.”

“So what do you think about going clear out to Iowa for training?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never been west of Chicago.”

“Neither have I.”

“I’ve read that it’s mostly farm country. Lots of corn and pigs.”

The two women drifted into their own thoughts as they looked over the others. Before long, though, everyone chattered about what they might have gotten themselves into. By sunset, the rattle and sway of the train had Bobbi drifting toward sleep, but she was apparently not alone. Since they couldn’t see anything on the prairie under a waxing sliver of a moon, the women began climbing into their berths, Bobbi above and Dottie and a small-town girl from Strongsville named Shirley Shank below. Before she slept, Bobbi’s mind drifted back to the miserable three days in Buffalo that led to her joining the WAACs.

She started, sitting up and bumping her head. When I got out-if-town gigs, I could have just made sure I took enough cash along when I traveled so that I could get home.

“You okay up there?”

“Yeah, I just thought of something.”

She rolled over and adjusted her pillow. I could have gone back to Danceland or the DownBeat. She rolled onto her back and stared at the swaying ceiling. Hope I haven’t made an awful mistake. Her eyes closed as she began to doze. Hope I can get a job when this is over.

At ten o’clock the following evening, Bobbi stepped off the train in a cloud of soot and smog that smelled like oil and cinders. She stood on the platform for a moment, suitcase clutched in her right hand and purse slung over her left shoulder, bouncing against her overnight bag. She noticed the sky first—all 360 degrees of it. Black and empty, it felt like she could just float up into it like a hot air balloon. She gazed into the distance for a few moments, getting her bearings.

“There’s nothing out here,” she whispered.

Dottie nodded and Bobbi stood transfixed by the sheer openness of the plains. She’d never imagined anything quite like this. Sweeping the country around the platform, she looked off to her right and nudged Dottie.

“No lights. Not a one. Doesn’t anybody live out here?”

Dottie shook her head.

Bobbi peered around, trying to get an idea of what she ‘d gotten into. She noticed two women in uniform with armbands that said WAAC standing beside a truck. She heard a couple of girls behind her whispering about a cattle truck. She turned toward them.

“Cattle truck?”

“That’s what it looks like.”

“Ugh.” Bobbi glanced down at the nearly-new suit she’d chosen for the trip.

Once the recruits had handed over their orders, the two Lieutenants told them how happy they were to see them, and waited while they claimed their luggage. Soon, Bobbi sat on a bench in the back of a truck that used to haul cows. She hung on to keep from careening into the other women as the truck ploughed over the first gravel road she’d ever seen. The four miles to Fort Des Moines seemed endless and she wondered again if she might have made a big mistake.

Shaken and uncertain, she climbed out of the truck, grateful for the two soldiers who helped her jump out, because her straight skirt didn’t lend itself to jumping. She rejoiced to have her feet on solid ground.

“Where are the buildings?”

“All around you,” said one of the women, gesturing.

“But they’re just–very short.”

“This is the Great Plains.”

Bobbi kept looking for something taller than the low structure she saw in front of her–about fifty feet across a stretch of dirt, gravel, and a little bit of brown grass. To her left stood three two-story buildings lit by bare electric bulbs.

“It all looks so . . . bare.”

In the middle of an area by the buildings, two tables supported piles of bed linens and towels—with a WAAC officer sitting behind one. She told them that some of their company had already arrived and had settled into the barracks. Then she invited them to line up, step up to the table, and give names and serial numbers.

Bobbi stepped up in turn. “Bobbi Bowen, A509027.”

She took her two sheets, one pillowcase, and three towels. Assigned to the First Platoon building, second floor, seventh bed on the right, she walked over to the building, still taking in the desolation around her, climbed the stairs, and stood in the doorway, gazing at everything in military order—beds lined up with foot lockers placed precisely at their ends, wall lockers perfectly aligned with the beds. She walked in and found her spot. She glanced at the woman in the next bed who seemed absorbed in a book, then quickly made her own bed, as the others filed in. She grabbed her pajamas and found her way down the inside stairs to the latrine where she showered, washed her face, and brushed her teeth. Stretched on her bunk, she turned to the woman with the book.

“Hi,” she said, stretching out her hand, “I’m Bobbi Bowen.”

The other woman introduced herself as Bonnie Anderson. She said she haled from a farm in North Dakota and arrived a couple of hours earlier on a train from Fargo. Bobbi noticed that everyone else in the barracks chattered away, curling their hair, filing their nails, writing letters—but mostly chattering. They wouldn’t do very much of that in the days to come.

Fort Des Moines

When you buy a movie, sometimes you get the extended version with the out takes. What follows is one of the out takes from The Reluctant Canary Sings. At one point, I thought Bobbi Bowen would join the WAACs and I wrote some 20,000 words about her military career. This scene is her journey to boot camp, from the 20,000 words I deleted. (Well, I don’t throw anything away.)

Here’s a group of recruits marching to the trucks in daytime.

Here’s a group of recruits marching to the trucks in daytime.Three weeks later, she got orders to report to Union Station at 2814 Detroit Avenue, no later than 2:30 p.m. on Saturday, September 12. She’s in the Army now.

On the specified afternoon, Bobbi climbed into a taxi alone and stepped out a few minutes later in front of the Union Station arches, slinging her purse over her shoulder, grabbing her overnight bag in her right hand, and hauling her battered suitcase up the steps with her left. Inside the high, vaulted concourse, she walked into bedlam with soldiers, sailors, their wives and girlfriends, and a few miscellaneous civilians stuffed into the waiting area. Sound echoing off the granite concourse added decibels to the confusion.

Bobbi spotted a particularly frenzied group of women, with photographers’ flashes going off and reporters scribbling in little notebooks. When she sidled over to see what was up, she discovered the WAACs. Someone pinned a gardenia on her and a reporter started shouting questions while a photographer snapped photos.

“Hey, aren’t you Bobbi Bowen?” the reporter demanded a couple of questions into his interview.

“Yes,” Bobbi said, smiling.

“Tell me again why you joined the WAACs.”

As she started to answer, she heard the recruiter yelling into a microphone. “All WAACs over here, please.”

Boy, he doesn’t know how to use a mic. She walked away from the reporter.

After a little farewell and congratulations speech, the women hurried off to Track A. There they boarded a New York Central Pullman heading for Fort Des Moines in the middle of what looked on the map in the library like a very blank space in the middle of the country.

As she stepped aboard, Bobbi wondered how long it would be before she returned to Cleveland. She knew one thing, though, she wouldn’t have to worry about the rent or the grocery money. She would have a roof over her head and plenty to eat for the duration.

She joined the first women to board and found a window seat where she sat humming Chattanooga Choo-Choo as the rest of the women found their seats. She’d changed her wake-sleep schedule during the last couple of weeks, but felt pretty groggy, and worried the rattle of the rails would lull her to sleep.

When another recruit sat across from her, though, she reached across with her right hand, “Bobbi Bowen.”

“Dorothy Cowan. People call me Dottie,” said her new friend, taking Bobbi’s hand in a warm grasp. “Pleased to meet you.”

“So what do you think about going clear out to Iowa for training?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never been west of Chicago.”

“Neither have I.”

“I’ve read that it’s mostly farm country. Lots of corn and pigs.”

The two women drifted into their own thoughts as they looked over the others. Before long, though, everyone chattered about what they might have gotten themselves into. By sunset, the rattle and sway of the train had Bobbi drifting toward sleep, but she was apparently not alone. Since they couldn’t see anything on the prairie under a waxing sliver of a moon, the women began climbing into their berths, Bobbi above and Dottie and a small-town girl from Strongsville named Shirley Shank below. Before she slept, Bobbi’s mind drifted back to the miserable three days in Buffalo that led to her joining the WAACs.

She started, sitting up and bumping her head. When I got out-if-town gigs, I could have just made sure I took enough cash along when I traveled so that I could get home.

“You okay up there?”

“Yeah, I just thought of something.”

She rolled over and adjusted her pillow. I could have gone back to Danceland or the DownBeat. She rolled onto her back and stared at the swaying ceiling. Hope I haven’t made an awful mistake. Her eyes closed as she began to doze. Hope I can get a job when this is over.

At ten o’clock the following evening, Bobbi stepped off the train in a cloud of soot and smog that smelled like oil and cinders. She stood on the platform for a moment, suitcase clutched in her right hand and purse slung over her left shoulder, bouncing against her overnight bag. She noticed the sky first—all 360 degrees of it. Black and empty, it felt like she could just float up into it like a hot air balloon. She gazed into the distance for a few moments, getting her bearings.

“There’s nothing out here,” she whispered.

Dottie nodded and Bobbi stood transfixed by the sheer openness of the plains. She’d never imagined anything quite like this. Sweeping the country around the platform, she looked off to her right and nudged Dottie.

“No lights. Not a one. Doesn’t anybody live out here?”

Dottie shook her head.

Bobbi peered around, trying to get an idea of what she ‘d gotten into. She noticed two women in uniform with armbands that said WAAC standing beside a truck. She heard a couple of girls behind her whispering about a cattle truck. She turned toward them.

“Cattle truck?”

“That’s what it looks like.”

“Ugh.” Bobbi glanced down at the nearly-new suit she’d chosen for the trip.

Once the recruits had handed over their orders, the two Lieutenants told them how happy they were to see them, and waited while they claimed their luggage. Soon, Bobbi sat on a bench in the back of a truck that used to haul cows. She hung on to keep from careening into the other women as the truck ploughed over the first gravel road she’d ever seen. The four miles to Fort Des Moines seemed endless and she wondered again if she might have made a big mistake.

Shaken and uncertain, she climbed out of the truck, grateful for the two soldiers who helped her jump out, because her straight skirt didn’t lend itself to jumping. She rejoiced to have her feet on solid ground.

“Where are the buildings?”

“All around you,” said one of the women, gesturing.

“But they’re just–very short.”

“This is the Great Plains.”

Bobbi kept looking for something taller than the low structure she saw in front of her–about fifty feet across a stretch of dirt, gravel, and a little bit of brown grass. To her left stood three two-story buildings lit by bare electric bulbs.

“It all looks so . . . bare.”

In the middle of an area by the buildings, two tables supported piles of bed linens and towels—with a WAAC officer sitting behind one. She told them that some of their company had already arrived and had settled into the barracks. Then she invited them to line up, step up to the table, and give names and serial numbers.

Bobbi stepped up in turn. “Bobbi Bowen, A509027.”

She took her two sheets, one pillowcase, and three towels. Assigned to the First Platoon building, second floor, seventh bed on the right, she walked over to the building, still taking in the desolation around her, climbed the stairs, and stood in the doorway, gazing at everything in military order—beds lined up with foot lockers placed precisely at their ends, wall lockers perfectly aligned with the beds. She walked in and found her spot. She glanced at the woman in the next bed who seemed absorbed in a book, then quickly made her own bed, as the others filed in. She grabbed her pajamas and found her way down the inside stairs to the latrine where she showered, washed her face, and brushed her teeth. Stretched on her bunk, she turned to the woman with the book.

“Hi,” she said, stretching out her hand, “I’m Bobbi Bowen.”

The other woman introduced herself as Bonnie Anderson. She said she haled from a farm in North Dakota and arrived a couple of hours earlier on a train from Fargo. Bobbi noticed that everyone else in the barracks chattered away, curling their hair, filing their nails, writing letters—but mostly chattering. They wouldn’t do very much of that in the days to come.