Stephen Morris's Blog, page 29

January 19, 2018

“There’s gold in them thar fleece!”

Jason returns with the Golden Fleece, shown on an Apulian red-figure calyx krater, ca. 340–330 BC

The California gold rush began on January 24, 1848 with the accidental discovery of gold in the water during the construction of Sutter’s sawmill. When President Polk announced the discovery later that year, it caused a national and international sensation and the “Forty-Niners” swooped down to begin sifting and panning for gold in the streams and rivers of California.

Gold has been associated with wealth and opulence throughout history. It is especially associated with gods and divinity and royalty. Gold coins protect people from hunger and poverty. Gold coins in the Tarot (Pentacles) deal with earthly, daily experiences related to work and endeavors that support our emotional and physical well-being.

Gold is mentioned in Greek mythology for examples as varied as King Midas, the Golden Fleece stolen by Jason which possessed the power of resurrection, and the Golden Apples of Hesperides. The Golden Apples bestowed immortality on whoever ate them. Gold has always been associated with the eternal, the unending, incorruptible and embracing powers of the divine. The color and shining quality of gold continues to be associated with the sun and the sacred masculine.

There is a fascinating connection between the Golden Fleece and the California gold rush. A widespread interpretation relates the myth of the Golden Fleece to a method of washing gold from streams, which was well attested from c. 5th century BC in the region of Georgia to the east of the Black Sea. (The myths of the Golden Fleece say that the Fleece was kept in Colchis, i.e. the modern Georgia in Eastern Europe.) Sheep fleeces, sometimes stretched over a wood frame, would be submerged in the stream and gold flecks borne down from upstream would collect in them. The fleeces would be hung in trees to dry before the gold was shaken or combed out. Collecting gold flecks from the rivers was what the Forty-Niners would do in California, often using pie pans to swirl the water in and then pour through filters–the same idea as the sheep fleeces.

Gold represents the best in us but also brings out the worst in people. Legends of Aztec and Inca gold drove the Conquistadores to seize the Native American empires. Jealousy and Greed, simmering beneath the surface of our emotions, are brought out into the open when we see someone else has something–such as gold–that we want for ourselves.

Click here to read more about folklore associated with gold.

The Fool, one of the Major Arcana of the Tarot, shows a golden sky that the pilgrim is stepping off into. He trusts that the universe will protect and shield him from exterior evil as well as from his own worst instincts.

The post “There’s gold in them thar fleece!” appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

January 12, 2018

St. Antony

Coptic icon of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and the 3 angels at Mamre; dated AD 1497. An inscription along the bottom asks the Lord to remember an archpriest’s son named Antony.

My partner Elliot was recently in Egypt and brought me home a beautiful book of Coptic icons as a gift. (I took these photos from the icons in the book. So gorgeous! Thank you, Elliot!)

Although many saints from Egypt have played fundamental roles in establishing basic Christian understandings of God and Christ (such as SS. Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria in the 4th and 5th centuries), another saint from Egypt has been nearly just as important: St. Antony, the first monk to found a monastic community. His life story, written down by St. Athanasius, has been said to have been nearly as popular as the New Testament and to have had nearly as big an impact on Western civilization.

Antony was not the first monk that we know of–that was St. Paul the hermit, who also lived in the Egyptian desert. But St. Antony was the first to establish a community of monks living in the desert. (There were also communities of nuns living in cities already when he went out into the desert for the first time.) There were soon thereafter huge “cities” of monks living in the deserts of Egypt and then across the Middle East and then across Western and Eastern Europe. The monastic centers that sprang up helped preserve ancient books and civilization and philosophy as well as spread Christian theology, literature, and liturgical practice.

St. Antony is the patron saint of butchers and pig farmers. His feast day, January 17, is an important date in Come Hell or High Water, Part 1: Wellspring.

In this chapter, a young man attempts to steal donations from a church in medieval Prague but it is the parish church of the butchers’ guild. The butchers find the young man and cut off his arm and hung it near the front door of the church as a warning to anyone who would attempt to steal from the church in the future. The arm is still hanging there in St. Jakub’s church, near the Old Town Square.

Coptic icon of Apostle Peter in the Coptic Museum (Egypt).

The post St. Antony appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

January 5, 2018

Wise Men Finally Arrive–Only 2 Years After the Shepherds!

Master of Vyšší Brod, a Bohemian master, c. 1350. The influence of Italian Byzantine painting was strong in the court of Charles IV.

According to the New Testament, the wise men arrived in Bethlehem when Jesus was already two years old! By then, the manger had been put away and the shepherds had all gone home. But the wise men (“magi”) had seen the conjunction (“star”) in the sky and had travelled from Babylon to Palestine to bring their gifts to the newborn King.

“We have seen his star in the East,” the magi told King Herod. “We have come to worship him.”

This news was a surprise to King Herod. He had no idea that a new King of the Jews had been born and had clearly NOT seen the star the magi had. What was the “star” which the magi claimed they had seen and which had told them to come find the newborn King in Judea? Since no one in Jerusalem seems to have seen it, the star could not have been a bright light in the sky or they would have noticed it. Since the Gospel text says that Herod later had all the boys aged two years or younger killed in his attempt to kill the Christ Child, the “star” must have been an astronomical event of some sort rather than a bright light or all the other parents whose children were butchered by Herod’s soldiers would have pointed out the house and said, “No! Not our children — the boy you want is in that house! There!” Also, the magi evidently had seen the star at least 2 years before and it had taken them that long to travel to Jerusalem.

When the wise men did finally arrive in Bethlehem, they are shown presenting their gifts to the Christ Child in the lap of his Virgin Mother. The oldest of the wise men is always in such a hurry to bow down before Christ that he trips and steps on his crown, as in the altarpiece below. (Click here to see a stunning collection of Nativity scenes, some with the shepherds and some with the wise men.)

I remember reading reports in December 1975 (my senior year of high school!) that the “star” was in fact a conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter in the constellation Pisces — and that this conjunction occurs once every 800 years! The magi, being astrologers, would have understood this to mean that a great king (Jupiter) who would usher in the End of Days (Saturn) was being born in Judea (Pisces). This conjunction occurred in December 1975, according to these reports, but I was unable to see it as I was not sure exactly where to look in the sky or on which date(s) to look.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423 (Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi)

The post Wise Men Finally Arrive–Only 2 Years After the Shepherds! appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 29, 2017

A Christmas Goldfinch

Madonna and Child, by Carlo Crivelli (1480); note the goldfinch in the Christ Child’s grasp

Very often in traditional depictions of the Virgin and Christ Child, there is a goldfinch in the baby’s grasp. Why?

The most simple reason might be that in the 14th century it was common for young children to keep tame birds as pets. Christ’s holding a bird allows a parent or a child to recognize his human nature, to identify with him. Despite the angels and the celestial gold background, the viewer is reminded that God lived and died as a man upon the earth.

But when is traditional Christian art ever simple? Or easy?

The goldfinch appears in depictions of Christ’s birth or during his childhood because it was said that when Christ was carrying the cross to Calvary a small bird – sometimes a goldfinch, sometimes a robin – flew down and plucked one of the thorns from the crown around his head. Some of Christ’s blood splashed onto the bird as it drew the thorn out, and to this day goldfinches and robins have spots of red on their plumage. Since goldfinches are also known to eat and nest among thorns, the goldfinch is often read as a prefiguration of Christ’s Passion.

The bird could also be seen as a symbol of the Resurrection of Christ. A non-Biblical legend popular in the Middle Ages related how the child Jesus, when playing with some clay birds that his friends had given to him, bought them to life. Medieval theologians saw this as an allegory of his own coming back from the dead.

Medieval Europeans also saw the goldfinch as a protector against the plague. Since classical times superstition had credited a mythical bird – the charadrius – with the ability to take on the disease of any man who looked it in the eye. The charadrius was sometimes represented as a goldfinch. Perhaps Christ’s finch offers the worshiper protection against the seemingly unstoppable contagion.

Also, since Ancient Egypt, the human soul had been represented in religious art by a small bird. We see the “Ba” (the soul-bird) on a detail of an Egyptian coffins. A very general reading of the goldfinch might, therefore, remind the viewer that his soul is ‘in the hands’ of God.

Curious about that big cucumber hanging from the apple tree? Hmmm… Read a VERY interesting interpretation of it AND other details of this painting here.

Remember the classic “I Want a Hippopotamus for Christmas“? I want a goldfinch!

The post A Christmas Goldfinch appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 22, 2017

The Cave of Bethlehem

Eastern Orthodox icon of the birth of Christ by St. Andrei Rublev, 15th century. Note that the shepherd speaking with St. Joseph in the lower left is shown in profile, a pose reserved only for this shepherd, the Devil, and for Judas Iscariot and which indicates their interior wickedness and efforts to hide themselves from God. Also, the cave in which Christ is born is painted with the same absolute black pigment — unmixed with any other dark colors, which is more usual — as is the tomb of Christ or the abyss of Hell, into which the Divine Presence has entered.

We talk about Christ being born in a manger, in a stable and most crèche scenes have the manger inside a straw-roofed hut. But traditional depictions based on ancient models, like the icon above, show the manger inside a cave instead of a straw-roofed hut. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem also marks the traditional place of the manger inside a cave beneath the church. Why?

In the Middle East, animals were often stabled in the small caves that dotted the countryside. The inn at Bethlehem that offered a place to Joseph and Mary doubtless had a stable-cave attached. But in western Europe during the 1200s, when it began to be common to erect crèche scenes, the stables there that people were used to seeing were huts. Not caves. So Europeans and Americans expect to see a manger in a hut, not a cave. But the cave was the more likely, original, and actual location of the manger.

A lot of traditional poetry for both Christmas and Good Friday point out that Christ was born and buried in a cave that belonged to someone else, each time protected by a man named Joseph. His swaddling bands, the strips of cloth a baby was wrapped in to keep him/her warm and cozy, look like a the strips of cloth a corpse might be wrapped in. The manger itself looks like a coffin. The celebration of the incarnation and birth of Christ already points to the celebration of his death and resurrection.

In Orthodox icons (such as the one above), the Star of Bethlehem is often depicted not as a bright light but as a dark aureola, a semicircle at the top of the icon, indicating the “divine darkness” or Uncreated Light of Divine grace, with a ray pointing to “the place where the young child lay” (Matt 2:9). Sometimes the faint image of an angel is drawn inside the dark semi-circle, pointing the way for the Magi.

The post The Cave of Bethlehem appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 18, 2017

Good Yule 2017!

Yule or Yuletide (“Yule time”) was a religious festival observed by the Germanic peoples, later being absorbed into and equated with Christmas. Scholars have connected the celebration to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin and the pagan Anglo-Saxon Modranicht.

Terms with an etymological equivalent to Yule are used in the Nordic countries for Christmas with its religious rites, but also for the holidays of this season. Yule is also used to a lesser extent in English-speaking countries to refer to Christmas. Customs such as the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, and others stem from Yule.

Yule is the modern English representative of the Old English words ġéol or ġéohol and ġéola or ġéoli, with the former indicating the 12-day festival of “Yule” (later: “Christmastime”) and the latter indicating the month of “Yule”, whereby ǽrra ġéola referred to the period before the Yule festival (December) and æftera ġéola referred to the period after Yule (January). Both words are thought to be derived from Common Germanic, and are cognate to Gothic (fruma) jiuleis and Old Norse (Icelandic and Faroese) jól (Danish and Swedish jul and Norwegian jul or jol) as well as ýlir, Estonian jõulud and Finnish joulu. The etymological pedigree of the word, however, remains uncertain, though numerous speculative attempts have been made to find Indo-European cognates outside the Germanic group, too.

The noun Yuletide is first attested from around 1475.

The word is attested in an explicitly pre-Christian context primarily in Old Norse. Among many others, the long-bearded god Odin bears the names jólfaðr (Old Norse ‘Yule father’) and jólnir (Old Norse ‘the Yule one’). In plural (Old Norse jólnar; ‘the Yule ones’) may refer to the Norse gods in general. In Old Norse poetry, the word is often employed as a synonym for ‘feast.’

The post Good Yule 2017! appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 11, 2017

Santa Lucia

Check out this website to make your own wreath-and-candle crown!

I remember studying about Santa Lucia in third grade when Scandinavia was the Social Studies unit. (I also remember the teacher saying that reindeer herding was one of the primary occupations in Finland and I wanted to ask, “How can anyone herd reindeer when they can fly?!” But something told me to keep my mouth shut. I’m glad I did.) Three years ago, I was also able to visit her relics which are currently kept in Venice.

Saint Lucy’s Day, is celebrated on 13 December, commemorating Saint Lucy (a 3rd-century martyr under the Great Persecution of Diocletian), who according to legend brought “food and aid to Christians hiding in the catacombs” wearing a candle-lit wreath on her head to “light her way and leave her hands free to carry as much food as possible”. Her feast once coincided with the Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year before calendar reforms, so her feast day has become a Christian festival of light.

Saint Lucy’s Day is celebrated most commonly in Scandinavia, with their long dark winters, where it is a major feast day, and in Italy, with each country highlighting a different aspect of the story. In Scandinavia, where Saint Lucy is called Santa Lucia, she is represented as a lady in a white dress (a symbol of a Christian’s white baptismal robe) and red sash (symbolizing the blood of her martyrdom) with a crown or wreath of candles on her head. In Norway, Sweden and Swedish-speaking regions of Finland, as songs are sung, girls dressed as Saint Lucy carry cookies and saffron buns in procession, which symbolizes bringing the light of Christianity throughout world darkness.

St. Lucy is the patron saint of the city of Syracuse (Sicily). On 13 December a silver statue of St. Lucy containing her relics is paraded through the streets before returning to the Cathedral of Syracuse. Sicilians recall a legend that holds that a famine ended on her feast day when ships loaded with grain entered the harbor. Here, it is traditional to eat whole grains instead of bread on 13 December. This usually takes the form of cuccia, a dish of boiled wheat berries often mixed with ricotta and honey, or sometimes served as a savory soup with beans.

St. Lucy is also popular among children in some other regions of Italy, where she is said to bring gifts to good children and coal to bad ones the night between 12 and 13 December. According to tradition, she arrives in the company of a donkey and her escort, Castaldo. Children are asked to leave some coffee for Lucia, a carrot for the donkey and a glass of wine for Castaldo. They must not watch Santa Lucia delivering these gifts, or she will throw ashes in their eyes, temporarily blinding them.

I think that in the United States, Santa Claus might appreciate a cup of coffee as well, more than milk and cookies!

The post Santa Lucia appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

December 4, 2017

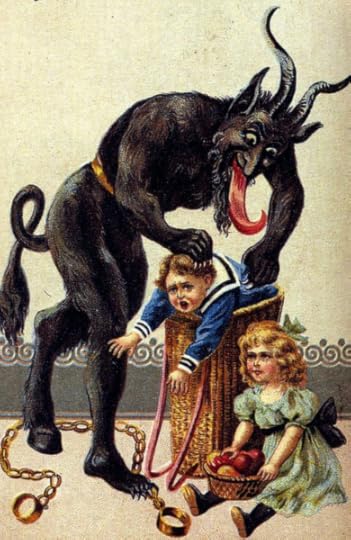

Who Comes to YOUR House on December 6?

Traditionally on December 5th and 6th, St. Nicholas walks from house to house in the cities and villages of Alpine and Central Europe to admonish and laud young and old. In the Alpine regions, he is accompanied by a Krampus (an evil creature, a devil of sorts), who is going to punish the bad children and adults on St. Nicholas′ command. For the honest children he normally has little presents. In Prague and the Czech-speaking areas of Central Europe, the čert (a clearly demonic character) accompanies St. Nicholas.

In Come Hell or High Water, both St. Nicholas and his čert appear:

“It was commonly supposed [in 1356] that St. Nicholas, as he made his rounds bestowing gifts on children and the needy, was accompanied by both a tar-covered čert, a pitch-black devil, as well as a bright and glorious andel, an angel of light, who each argued for or against the worthiness of the recipient of the saint’s benefactions. The čert was always ready, at the slightest nod from the saint, to carry away the unworthy beggar or misbehaving child and–throughout the year–parents could always warn their children that they might be carried away by the čert….”

St. Nicholas himself is a Christian figure, the fourth century bishop of Myra. As son of a well-situated family, he started to help poor people who lived in deep poverty. He was supposed to have miraculous vigor and so he became patron of the seamen, children and poor people. (See a previous post about St. Nicholas and his care for the poor here.) In most modern versions of the St. Nicholas story, he is accompanied by a monster or servant (the Dutch describe his assistant as Black Peter) who punishes the bad children while Nicholas himself rewards the well-behaved children.

The figure of the Krampus is based on pre-Christian custom. The Krampusse not only punish the bad children but had the function at one time of driving out the winter devils and blizzard sprites. Originally the custom of the Krampus was spread over all of Austria but was forbidden by the Catholic Church during the Inquisition. It was prohibited by death to masquerade as a devil or an evil creature and so this custom only survived in some remote, inaccessible, regions of the Alps from where it slowly spread back across the western parts of Austria again. Today the Krampusse revels are especially popular in Salzburg. As many times as I have been to Salzburg, I have never been there during Krampusse-time; I would dearly love to be there to see the processions and parades of costumed characters in the streets.

St. Nicholas and the Krampus procession in Salzburg (2010); photo by Charlotte Anne Brady.

Krampus revels at the Salzburg Christmas Market, 2011; photo by Neumayr/MMV 05.12.2011

The post Who Comes to YOUR House on December 6? appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 27, 2017

St. Andrew’s Day

Fran Francken II (Flanders, Antwerp, 1581-1642) painting of St. Andrew’s crucifixion, circa 1620, on exhibit in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

St. Andrew, the first man to join Christ as an apostle, was crucified on an X-shaped cross. He is now widely venerated as the patron of Scotland, Russia, and many other places. His X-shaped cross appears on the flags of many countries that looked to him for protection. His feast–on November 29 in some places and November 30 in other places–is both especially popular for magic that reveals a young woman’s future husband and was believed to be the start of the most popular time for vampires to come hunt the living, which would last until Saint George’s Eve (22 April).

In Romania, it is customary for young women to put 41 grains of wheat beneath their pillow before they go to sleep, and if they dream that someone is coming to steal their grains that means that they are going to get married next year. Also in some other parts of the country the young women light a candle from the Easter celebration and bring it, at midnight, to a fountain. They ask Saint Andrew to let them glimpse their future husband. Saint Andrew is invoked to ward off wolves, who are thought to be able to eat any animal they want on this night, and to speak to humans. A human hearing a wolf speak to him will die.

In Póvoa de Varzim, an ancient fishing town in Portugal there is Cape Santo André (Portuguese for “Saint Andrew”) and near the cape there are small pits in the rocks that the people believe these are footprints of Saint Andrew. Saint Andrew Chapel there was built in the Middle Ages and is the burial site of drowned fishermen found at the cape. (St. Andrew was also a fisherman in the New Testament.) Fishermen also asked St. Andrew for help while fishing.

It was common to see groups of fishermen, holding candles in their hands, making a pilgrimage to the Cape’s chapel on Saint Andrew’s Eve. Many might still believe that any Portuguese fisherman who does not visit Santo André in life will have to make the pilgrimage after they die.

The post St. Andrew’s Day appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.

November 20, 2017

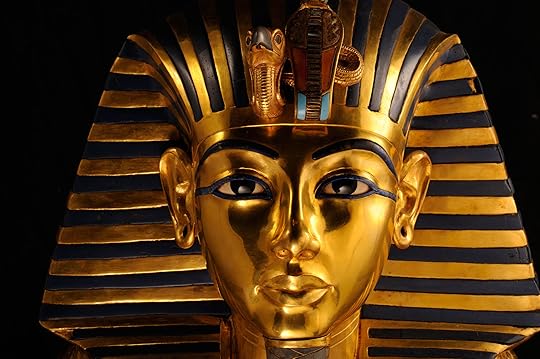

King Tut

Doesn’t everyone recognize the famous funerary mask of King Tut? It was on November 26, 1922, that Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon first went inside the tomb of King Tutankhamen. (Photograph by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic Creative)

Who doesn’t know about the curse of King Tut that killed everyone who dared disturb his tomb? Or that famous Mummy that hunted down those who disturbed his rest? But how did the Egyptians actually turn bodies into mummies?

I remember one time in the Egyptian Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that a mother was trying to calm a worried or frightened child, “Don’t worry! They took the bodies out of the mummies before they put them on display!” Of course, if that were true there would be no mummy left because removing the body would mean unraveling the bandages and destroy the mummy that we see on display.

The Egyptians thought that the dead would need their bodies in a recognizable form in order to reanimate them in the afterlife. The heat and dryness of the sand dehydrated the bodies quickly, often–but not always–creating lifelike and natural ‘mummies’ for the poor. But the wealthy wanted more care taken to preserve their bodies in order to be sure that they would actually have a usable mummy when they needed it.

Anubis was the jackal headed god of the dead–we have all seen the representations of Anubis in the movies about mummies. He was closely associated with mummification and embalming, so the chief priest/embalming overseer wore a mask of Anubis.

The priests would first insert a hook through a hole near the nose and pull out part of the brain because it and the other internal organs would rot and might prevent proper mummification. They would also make a cut on the left side of the body near the stomach and remove all the other internal organs as well. Once dried out, the lungs, intestines, stomach, and liver would be preserved each in their own canopic jar, apart from the mummy itself. The heart itself would be placed back inside the corpse.

Then they would rinse inside of body with wine and spices and cover the corpse with natron (salt) for 70 days. Halfway through this process, around the 40-day mark, they would stuff the body with linen or sand to give it a more human shape and at the end of the 70 days they would wrap the body from head to toe in bandages. That’s the mummy we see today, all wrapped up in strips of bandages.

Of course, the traditional “swaddling clothes” or “swaddling bands” that babies were wrapped in were very similar to the bandages that would be used to wrap up a mummy so the images of babies in ancient or medieval art often look very similar to mummies as well. Except that the baby’s face is not covered! (Medieval Christian art often depicted a person’s soul as one of these “mummified” babies.)

The post King Tut appeared first on Stephen Morris, author.