P.A. Peirson's Blog, page 2

May 30, 2012

HAUNTED SHIPS: THE STAR OF INDIA – PART II

How did San Diego's Star of India, the world's oldest seafaring ship, earn her reputation for being haunted? Why is she the focus of frequent paranormal investigations? A disturbing history of collisions, mutiny, and death may be the answer.

To recap my previous post (5/26/12): Star of India, christened the Euterpe, was launched on November 14, 1863 and first used in the Indian jute trade. Enduring a rather hard-luck beginning, she was sold in 1871 to the Shaw Sevill line, which partnered with the White Star line. The latter’s fleet included the ill-fated Titanic. Now a transportation ship for passengers, the Euterpe’s strange history of violence and tragedy continued:

Part II -- John Campbell

I must go down to the sea again, to the vagrant gypsy life,To the gull’s way and the whale’s way, where the wind’s like a whetted knife …

On April 19, 1884, Euterpe set sail from the port of Glasgow bound for Dunedin, New Zealand. Her prize cargo: Scottish emigrants seeking a new life and, in many cases, religious freedom, in the South Island provinces. But hiding deep in Euterpe’s dark hold was secret cargo—the key player in a story that would end in tragedy.

The voyage had begun badly. Euterpe was scheduled to leave on April 9 and had departed Glasgow as planned under the command of Captain George Edward Hoyle. However, the ship had not even cleared the Clyde River before colliding with the British steamer Canadian. The subsequent lay-up for repairs took ten days—time enough for a young stowaway by the name of John Campbell to slip aboard and hide deep in the ship’s hold amidst stacked and secured crates, barrels, brass-fitted trunks and chests, bundled goods, stacks of canvas, and piles of thick, neatly coiled rope. Here in the musty, sour dampness, with nothing but the inevitable ship rats for company, John played a perilous waiting game. Port authorities and ship’s captains did not look kindly on stowaways.

But luck favored John, and he remained undetected until Euterpe was well out to sea. Playing a skillful game of hide-and-seek with crew and passengers, he avoided capture for several weeks, holing up in various parts of the ship and living on pilfered food from the emigrants’ dreary fare of salted meat, biscuits, and oatmeal. He was only in his teens, but a life of grinding poverty had sharpened his wits and kindled a fierce desire to seek adventure at sea or perhaps a change of fortune in a new land. We’ll never know for certain which.

John was eventually caught and put to work. He soon learned first hand that keeping a ship “ship shape” is a never-ending cycle of backbreaking, often dirty, frequently dangerous work. Still, the young stowaway proved willing and capable. One day, he was sent aloft. Scrambling high into the mainmast rigging was exhilarating—the wind clean and bracing; blue ocean as far as the eye could see. Impulsively John raised a friendly hand to a fellow crewman. It was a fatal mistake. He felt himself slipping, and in a terrifying split second, John lost his footing and helplessly plunged 100 feet to the deck below. Both his legs were shattered. The poor lad hung on for three agonizing days before dying. As was fitting, his remains were consigned to the Deep.

John Campbell risked all and realized his dream of adventure and a new life for only briefly. Yet those few weeks may have been the happiest he had known. Is the young stowaway still aboard? There are those that believe so. Stand quietly on the deck near the mainmast where John fell. Do you sense a presence or a feeling of sadness? If you are lucky, the touch of cold, ghostly “hand” may let you know that John is near.

___________

So, one-by-one, the square-rigged sailing ship's ghostly crew was growing. Today, she is a favorite supernatural destination among ghost hunters. What else was in store for her? How did the Euterpe become the Star of India? That and more in my next post about this "spirited", history-haunted ship.Happy Hauntings!

Published on May 30, 2012 18:09

May 26, 2012

Haunted Ships: The Star of India

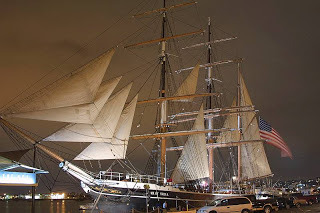

Recently, I came across my photos of the famed Star of India, the world's oldest seafaring ship. She is considered the crown jewel of the Maritime Museum in San Diego, CA. Inspired once more by this beautiful ship with her intriguing history, I’d like to share a few of her stories—historical and haunted—in the next few posts. These were researched and written while toying with a book idea.

I must go down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and the sky,And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by. … John Masefield “Sea Fever”

Step aboard the Star of India and you step back to a time when tall ships roamed the seas, the world still held secrets, and faraway places beckoned with the promise of wealth, adventure, or a new beginning.

Tall ships, the most majestic of sea-faring vessels, ruled the seas for hundreds of years. These grand, traditional ships boasted three or more masts to which vast, white-canvas driving sails were laced to yards positioned square to each mast. A fully square-rigged ship could fly before the wind, and these swift ships, in their heyday, were the key to international commerce. Nevertheless their powerful fusion of wind, billowing canvas, and human muscle were no match for the steam engine. The reign of the tall ships declined in the late 1800s and came to an end after World War One.

It’s not difficult to believe that grand old ships like the Star of India are haunted—some perhaps more than others. And why not? Many set sail for distant shores with crews and passengers packed aboard, living elbow to elbow for weeks or months at a time—a microcosm of life in a pressure cooker of confinement. The voyagers would bring aboard all their expectations, dreams, fears, and sorrows. Add to the mix the inescapable tensions of the journey: unpredictable seas, foul weather, hunger, illness, uncertainty, and sometimes death. In such an environment, emotions are distilled down to their most raw, elemental form. Voyage after voyage, these powerful passions would be evoked and would seep into the very framework and fabric of the ship, from deck to cabins to the gloomy cargo hold—and decades later, people would feel them like a tactile echo and describe the ship as having a profound sense of history.

Then, of course, sometimes the tragic nature of events would leave behind the white, silent people who haunt a ship’s deck, whisper from the shadows, and glide past, felt but unseen, in the darkness of the hold.

A Hard-Luck Beginning

The Star of India actually began her life as a fully square-rigged ship christened Euterpe, after the Greek muse of music. She was built by Gibson, McDonald & Arnold in 1863 on the Isle of Man at the Ramsey shipyard—at that time a yard at the forefront of ship building. The iron-hulled Euterpe was an experiment of sorts; most vessels were still being built of wood. Rigged with royal sails and double topsails, she was launched on November 14, 1863, to be used in the Indian jute trade.

From the outset of her sailing career, bad luck was an invisible passenger aboard Euterpe. In January, 1864, she set sail from Liverpool bound for Calcutta under command of Captain William John Storry. Off the coast of Wales, a collision with a Spanish brig forced her to lay up in Anglesey for repairs. The angry crew turned mutinous and had to be jailed until the ship was back in working order. On her second trip, she was dismantled in a gale off the coast Madras (now known as Chennai) in the Bay of Bengal and barely limped into port. Euterpe’s ill-fortune pursued her on the return voyage from Calcutta to England with the peculiar death of Captain Storry. He was buried at sea

“We therefore commit his body to the deep, to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, when the Sea shall give up her dead …”

Over the next few years, Euterpe made four more relatively uneventful voyages to India. Then in 1871, she was purchased by the Shaw Sevill line of London mainly for transporting passengers and freight to New Zealand, with an occasional side trip to Australia, California, or Chile. It’s interesting to note that Shaw Sevill had a partner at this time: the White Star line, whose name is forever linked to the ill-fated ship Titanic, doomed to sink on her maiden voyage in 1912 after collision with an iceberg.___________

In my next post, I'll tell you the strange tale of stow-away John Campbell, whose ghost is still aboard, it seems.

Happy Hauntings!

Published on May 26, 2012 19:19

May 14, 2012

History Haunts Pasadena’s Colorado Street Bridge

On a recent jaunt to Pasadena, I was reminded of one of my favorite “haunted” sites, so I thought I’d share it with you. Actually, I always found it oddly charming, even before learning of its grim past. The spot I’m referring to is the Colorado Street Bridge, a.k.a. “suicide bridge.”

Colorado Street Bridge from ArroyoLocated in Pasadena, California, the historic—and some say haunted—Colorado Street Bridge spans the Arroyo Seco, an enormous gorge carved out by an intermittent stream of the same name. Since its construction in 1913, this magnificent bridge has been the site of a hundred or more suicides, most of these occurring in the 1930s during the Great Depression.

Colorado Street Bridge from ArroyoLocated in Pasadena, California, the historic—and some say haunted—Colorado Street Bridge spans the Arroyo Seco, an enormous gorge carved out by an intermittent stream of the same name. Since its construction in 1913, this magnificent bridge has been the site of a hundred or more suicides, most of these occurring in the 1930s during the Great Depression. The Arroyo itself has quite a history, which no doubt adds to the bridge’s dark charm.

The winding river valley of the Arroyo Seco extends from the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains and along the west edge of South Pasadena. Historically, it served as a corridor for wildlife and a hunting ground for the areas original inhabitants, the Hahamongna tribe.

During California’s mission era, control of the region that included the Arroyo Seco fell under Spanish rule when the Mission San Gabriel Archangel was established on September 8, 1771. Six decades later, that authority was handed over to a civil administrator, and the vast land holdings subsequently were deeded and passed to a number of different owners.

During the early 1800s, the Arroyo wilderness became a haunt for outlaws and thieves. Travelers and settlers alike were subject to attack. However, the arrival of the U.S. Army Camel Corps put a damper on these darker activities in the 1850s. Drivers for this curious pre-Civil War experiment—now little more than a footnote in Army history—brought their camels to the Arroyo for water and pasture.

In 1873, Thomas Elliott and a group of migrants trekked from Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois all the way to Southern California. These adventurers came looking for warm weather and cheap land and would become Pasadena’s founders. Drawn to the natural beauty of the area—in particular the Arroyo Seco— they purchased land along the river valley’s east bank and built their homes amidst orchards of walnuts, olives, and citrus trees. By the latter part of the 1880s, Pasadena had become a key stop along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, and the housing business was booming.

The turn of the century saw the rise of great tourist hotels as Pasadena became a winter resort for wealthy easterners. The Arroyo became a haven for artists and intellectuals during the early 1900s—a home to the Arts and Crafts Movement. Yet despite the regions growing popularity, traversing the Arroyo Seco remained an arduous task involving horses, wagons, and the often treacherous, steep slopes of the gorge.

Then in 1913, American civil engineer and prolific bridge designer J.A.L. Waddell was commissioned to design a bridge crossing the Arroyo, thus connecting Pasadena to Los Angeles. The result was a 1467-foot open-spandrel known as the Colorado Street Bridge— a work of art now considered an historic landmark.

The completed structure rose 150 feet above the Arroyo gorge—the tallest concrete bridge of its day. The first curvilinear bridge ever designed, its sweeping lines permitted the bridge’s 11 great arches to stand on the firmest ground of the Arroyo. Elegant white-globed light posts lined the structure on both sides. Curved seating bays provided pedestrians with rest areas along the bridge’s wide walkways. Over one million pounds of steel and approximately 14,000 barrels of cement were used in its construction.

In 1926, the Colorado Street bridge became part of national historic Route 66—the former U.S.Highway also known as The Mother Road, The Main Street of America, and The Will Rogers Highway. It continued to be part of Route 66 until 1940, when the Arroyo Seco Parkway opened.

Pasadena, like the rest of California and the nation, was hit hard by the economic collapse of the 1930s. The building market plummeted, property owners lost their holdings, and state-wide unemployment reached a staggering 28 percent by 1932.

It was during the Depression era that the Colorado Street bridge earned its nickname “suicide bridge” due to the high number of distraught individuals who hurled themselves from its dizzying heights to “end it all” in the gorge below. It is estimated that nearly 100 people have jumped to their deaths since the first suicide from the bridge on November 16, 1919—most of these deaths taking place during the Great Depression. (Pasadena Post, September 2, 1937, Page 7)

On May 1, 1937, one of the more sensational suicides occurred. A despondent mother first threw her baby over the bridge railing, then jumped to her death. Miraculously, the baby survived, having landed in the thick, supportive branches of a tree, from which she was later recovered.

Later that year, a jump-proof fence was put in place with hopes of ending the bridge deaths by suicide. At this time, official police records placed the total number of suicides at 79—15 women and 64 men. Sixty-three of the jumpers were non-residents, attracted by sensationalized suicide stories published in out-of-town magazines and newspapers. (Pasadena Post, September 2, 1937, Page 7)

Over the ensuing years, the bridge gradually fell into disrepair—still structurally sound but cosmetically shabby. Following California’s 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, city officials decided that the bridge required extensive renovation and, in the interim, should be closed to traffic.

Restored and rededicated on December 13, 1993, the Colorado Street bridge is again open for use. However, with its proximity to a major freeway, the structure has become only a minor thoroughfare, happily permitting it to preserve a charming air of nostalgia. With romantic street lamps and excellent views of the Rose Bowl to the north and the Arroyo Seco to the south, the bridge offers a quiet pedestrian stroll pleasantly evocative of another era. Each summer, the architectural landmark is the site of the Celebration on the Colorado Street Bridge, an evening of music, food, and family entertainment.

It is not surprising that unsettling tales of unexplained phenomena have arisen in connection with the Colorado Street bridge. View the sweeping structure on a foggy night, the globed lighting haloed with mist, the Arroyo wilderness below veiled and in shadow—it’s not hard to imagine that it is a haunted place. Today, hikers, teens prowling the Arroyo after sundown, and people camping along the stream bed beneath the bridge—many of these homeless, semi-permanent residents—have reported seeing ghostly figures, hearing mysterious sounds and voices, and seeing orbs. Some witnesses have reported feeling extremely unwelcome or sensing strong anger.

It is not surprising that unsettling tales of unexplained phenomena have arisen in connection with the Colorado Street bridge. View the sweeping structure on a foggy night, the globed lighting haloed with mist, the Arroyo wilderness below veiled and in shadow—it’s not hard to imagine that it is a haunted place. Today, hikers, teens prowling the Arroyo after sundown, and people camping along the stream bed beneath the bridge—many of these homeless, semi-permanent residents—have reported seeing ghostly figures, hearing mysterious sounds and voices, and seeing orbs. Some witnesses have reported feeling extremely unwelcome or sensing strong anger.A popular legend concerns the first death connected to the bridge. This supposedly occurred in 1913 when a worker lost his balance and fell into the wet concrete that was filling a form for one of the huge supporting pillars. By the time his absence was noted, it was too late to retrieve the body. Some people believe it is his spirit that beckons the despondent to jump to their deaths.

Though this particular story is unsubstantiated, there was a tragic death associated with construction of the bridge that may be the source. On August 1, 1913, span No. 9 of the bridge (still under construction) unaccountably gave way. Two hundred tons of liquid concrete and 100 tons of steel and wood cascaded to the bottom of the Arroyo, 120 feet below. Three workers fell with the wreckage. John Visco was killed instantly and two other men were severely injured. (Pasadena Star, August 2, 1913, Page 1)

Another interesting source for ghostly tales concerns a mental hospital. The slopes below the Pasadena-side entrance to the bridge formerly accommodated a sanitarium for housing the insane. Long since torn down, a bit of foundation, some steps, and a low wall are all that remain. The locale is now the site of a new condo development. It has been suggested that some manifestations are linked to that demolished asylum.

So, there you have it. Any haunted locales near you?

Happy Hauntings!

Published on May 14, 2012 15:46

P.A. Peirson's Blog

P.A. Peirson isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.