Cynthia Dewi Oka's Blog, page 3

February 20, 2013

The Next Big Thing

With gratitude to Vanessa Martir, Kiala Givehand and Lisa Marie Rollins for tagging me in The Next Big Thing! Please see below for links to their blogs, where you can find out more about their projects.

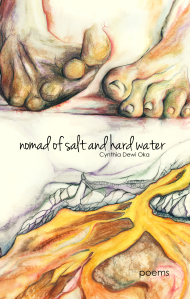

What is the title of your book? Nomad of Salt and Hard Water.

Where did the idea come from for the book? Nomad emerged out of my direct and inherited experiences of expulsion, displacement and wandering; of building and dismembering makeshift homes with shards of bone and memory; of passing through and being passed through.

It comes from my grandfather’s courage to jump on a boat at the turn of the century and start over in Indonesia after burying both his parents in southern China; from my grandmother’s determination to save her children as villagers under Japanese occupation burned and looted her home; from my mother’s tenacity surviving child labor and later on putting herself through nursing school at a time when Chinese-Indonesians were being massacred, outlawed from the vast majority of professions and deprived of citizenship; from my father’s hunger for a life of dignity where he did not have to hide, and his subsequent humiliation as an unemployable immigrant in Canada; from my search, as a survivor of male violence and a young teen mother, for refuge, sustenance, salve…which eventually brought me to that most resilient light belonging to people who have endured unspeakable dispossessions and yet continue to mend the world.

What genre does your book fall under? Poetry.

What songs would be in the soundtrack for your book?

Valley – Nneka

Breakdown – J Cole

Man Down – Rihanna

Intruder Alert – Lupe Fiasco

Exile – Shad

Look Into My Eyes – Outlandish

Cold War – Janelle Monae

I Need A Dollar – Aloe Blacc

Be Alright – Foreign Exchange

Regrets – Jay Z

Keep Livin – Jean Grae

I Remember – The Roots

Hometown Hero – Big K.R.I.T.

Soldier – Erykah Badu

Talkin Bout A Revolution – Tracy Chapman

Burnt Offering – Blue Scholars

Beautiful – India Arie

Did You Hear That Sound (Dreamtime Improv) – Abdullah Ibrahim

By Your Side – Sade

Move on Up – Curtis Mayfield

Ain’t Got No / I Got Life – Nina Simone

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Nomad is howl, prayer, amulet, anthem for the soul who sees with her feet; who wanders ruins and throbbing cities alike with nothing but sandals, toothpaste, grit; who collects calluses and matchsticks like holy things.

Is your book self-published or represented by an agency?

My book is published by Dinah Press, a new independent and collectively-run press. Visit http://www.dinahpress.com.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

It is very difficult to live without acknowledgment of your presence and purpose. You are at best treading water until one day, you can’t anymore, and you drown. I was inspired by the realization that I had to save my own life because no one else was going to do it.

Poetry is my calling, and before I embraced it, I was very lost. For years, I led double lives and half lives; in public I worked myself to the bone making ends meet, raising my son on my own and trying to look respectable doing it (no one will condemn you faster, when you find yourself embodying one of the “social problems of the era” and not being able to pull it off like a swanky haircut, than communities that you took for granted); in private and between shifts I wrote poems and struggled with thoughts about ending my life, every single day.

But the personal is political. One of the most insidious effects of our profoundly violent capitalist society, and I think what also makes it so tough to change, is that it is fueled by personal shame, which it metabolizes into greed, obedience, desperation, etc. Everyone – but especially those it systematically targets to be its scapegoats – are made to internalize all the devaluations, humiliations, ugliness of the entire collective as the very boundaries of our selves. Anything our souls are called to do must wade through, beat back, choke on layer after layer of rot and muck and shit that has been heaped on us, that in some cases end up merging with our cells. If our response to that calling dies before making it out, it will one day, bleed out of us and return to the earth. If it persists, it will birth a voice that carries in its edges, in its timbre, the depth of the hurt and hatred that has been marshaled against it, that it has had to cut through. But this is in fact how we keep each other’s fires from going out – through our willingness to reveal and be revealed.

I had reached that point where my legs were going numb in the water and I didn’t want anymore things to die in me. I wanted to model for my son what it meant to search for your life, to fight for what is rightfully yours, to offer as a hard-earned beauty what has been brutally broken in you.

I am also deeply indebted to those writers, thinkers, shit-starters whose words formed a constellation of stars around me; who sang, hollered, prophesied so I would have something to hold and follow in the dark. Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Joy Harjo, Lee Maracle, Lucille Clifton, Tony Morrison, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Finney, Ruth Forman, Rita Wong, Aracelis Girmay, Suheir Hammad, Malcolm X, Amiri Baraka, Raul Zurita, Pablo Neruda, Martin Espada, Derek Walcott, Yusef Komunyakaa, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Chris Abani, Tim Seibles, Patrick Rosal, Willie Perdomo…their poetry never ceased to remind me what was at stake.

What else about your book might pique a reader’s interest?

Nomad gave me the courage to recover and re-mix legends that were passed on to me through the power of image, rather than language. Legend is a story passed down through generations; it could refer to the person or thing that inspires the story in first place, hence, legacy, lineage. But legend is also a guide that allows you to decipher a map. It is how you learn to read landscape and extract textures, heights, distances, warmths – their continuances and ruptures – from what has otherwise been flattened.

Nomad embodies five distinct and converging legends: Daughter, Warrior, Oracle, Moon and Midwife, each of which begins a section of the book. While writing those, I truly learned to submit, to be a vehicle for something (spirit? voice?) much older, vaster, wiser than I could ever imagine being. It was a feeling of being filled, entrusted with fragments of a much greater memory to which my body was only one door.

My tagged writers are:

Seve Torres, Hari Alluri, David Maduli, Miriam Ching Yoon Louie, Andrea Walls and Rajiv Mohabir.

~

Please check out these sisters’ pages below as well -

Vanessa Martir: http://vanessamartir.wordpress.com/

Kiala Givehand: http://givinghandscreative.blogspot.com/

Lisa Marie Rollins: http://birthproject.wordpress.com/

February 13, 2013

Sing Up the Bones

The February 14th Annual Women’s Memorial March has long been the most important event of the year for my son and I. It is a gathering and remembering led by the women of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside for their missing and murdered sisters, for whom no proper investigation or proceedings of justice have been served by any level of government. As members of what is well known to be the “poorest postal code” in Canada and a community besieged by the predatorial forces of gentrification, the lives and bodies of these women have been treated for decades as disposable and as collateral by the local authorities. Since 1991, women of the Downtown Eastside have been organizing to memorialize their deaths and disappearances, to keep their mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts, friends, lovers in the realm of public memory. For we are lost when we forget; for readiness for the long struggle comes from the courage of our hearts to break.

This is the first time in many years that my son and I will not be able to attend the March. As a survivor, former resident and worker in the Downtown Eastside, as a woman, an immigrant residing on occupied lands, a poet and most importantly, as a human being, my heart is preparing to enter the sacred ground at Main and Hastings tomorrow and to walk, and as I walk, to listen to their stories, to howl with their grief, to rejoice in the indestructible strength of memory, spirit, sisterhood and the desire for justice. I send this poem in place of my physical presence, I send this poem as prayer.

Please visit http://womensmemorialmarch.wordpress.... for more information about the March, and watch “Survival, Strength, Sisterhood: Power of Women in the Downtown Eastside” this film by organizer, warrior and friend Harsha Walia, with Alejandro Zuluaga, at http://vimeo.com/19877895.

Singing Up the Bones

~ in honor of the missing and murdered women of the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver, Unceded and Occupied Coast Salish Territories ~

we are called to the wind / our throat

unleashes / robe feather bannock

our bodies / beneath / the heat

of the drum

there is a war on our lives / a war

on our lives it looks like / pressed

suits and kevlar / double-decker

hearts / vintage / everything

is plunder / police-manned / rooftops

siege / of eagle and her / mercy we

come to bless / corners / soul’s

rain-bitten alleys / the blood-

thirst in husks of tongue / we / who wait

all our lives / to be / safe

in the quilts of our names / our dance

lightning / our breath / forbidden

street in death-row / city / no more

fallen / no more graves / in air sawed

by silence / skin the sun / sing

the drums that raise / the dead

December 17, 2012

to know beauty

Each year on your birthday, I see stars gather

their robes like queens at the seams of a black sea,

whispering to each other in a vernacular of light,

without sound but with all of the understanding

of the leaf, which blooms, sings and withers

according to the needs of each season.

How much have they witnessed and grieved

with their wrists bound to the heavens -

children with fish scales for eyes and fingertips

shredded like paper in the ravenous mills of the world,

children dying without the warmth of their skins,

whose still growing bones are crushed fine as lavender

by falling missiles, children whose mothers are the machetes

in their hands, children who translate lightning

into the speed of malnourished bodies in and out

of alleys, children in the shadows of steel bars,

who lay awake and skip rope to the cantatas of bullets,

children who dream of bread and pray for anything

to rupture the silence burning their lungs.

What wish would stars grant such warriors as these?

Morning’s smoke looms and mountains like armadas resume

their edges. What light cannot diminish

in me: your hands’ peninsula, the dimpled earth of your cheeks,

your velvet rise and fall against my nape.

I have not the age nor circumference to decipher

a tongue’s star, like murmurings of the near womb,

only faith that it is given to all children -

May you rise under the tutelage of mountains

to your fullest height, your spine incorruptible as cedar.

May you echo the prayer call of your ancestors

traveling by wind and coast into the crescents of your feet.

May you wash your body in moonlight and dance

to the thrum of dragonfly wings over fresh water.

May you carry your truth like the conch shell, which waits

for the worthy ear in the desert to reveal ocean’s pull.

May you never wait alone, for death or forgiveness,

may the water buffalo always be your loyal friend.

May you fight with the tenacity of the wolverine

against any foe who would strip you of your dignity.

May you wear your face like a miracle

for you have known beauty and survived.

-from nomad of salt and hard water (Dinah Press, 2012)

A tree at the main stage in Bethlehem with photos of Palestinian Children killed by Israeli attacks during the last war on Gaza. Photo by Elias Halabi.

December 13, 2012

Why Nomad?

Last week, I had the blessed experience of being interviewed by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, black feminist poet/scholar/priestess extraordinaire, about my book of poems, nomad of salt and hard water. She asked me a few excellent questions – by excellent I mean, they really challenged me to ponder and search before I could articulate a response – among them, why did you decide to delve into the nomad subjectivity? - which I share here because it flowered in me long past the interview.

Initially, it might seem a straightforward enough to assume that the nomad as a controlling (convenient?) metaphor might stem from my experience as an immigrant and descendant in a long line of diasporic/displaced people, not only in North America but in Indonesia, where I was born and lived for the first 10 years of my life. But in the process of writing this book I learned that the nomad for me embodies, not necessarily a category of identity, but a particular tension between a question and a decision about how to be in the world in relation to place and the Other.

The word “nomad” originates from the Greek nomas, which means “roaming, roving, wandering,” originally used in reference to shepherding tribes that move with their flocks to find grazing pastures. So whereas the migrant infers a removal – willing or forced – of a rooted self from a homeland to a foreign space, which even if it were not hostile entails a radical adaptation, the nomad infers routes, paths, crossings that are destinations in and of themselves. The nomad does not so much root herself in place as take with her roots from wherever she finds herself momentarily residing. Further, the idea of root functions for the nomad not so much as an amplifier of authenticity, but as a means to figure out how one needs to and can reinvent oneself at any given moment. Hence why the poem “here”, ends with the definition, “an emphatic form of this: we stay within distance of a breath, self ticking into soil, organs corrupting imperceptibly like the sudden yellow of an album; before the line scatters, only this here, a part kissing time into place” (Oka, p. 65).

Who is the nomad’s Other? I think my answer to that would be whoever belongs to a place, or places. This is not an oppositional relation, however, because the metaphoric nomad of the 21st century – crossing through brilliantly diverse, bureaucratic, massive and fragmented land/oceanscapes separated by vast distances – clearly depends on the Other for orientation, reflection and at times, protection. There is a radical vulnerability inherent to the nomad I encountered while writing this book, because she is after all, a subjectivity, a spirit, invented out of necessity, rather than a member of a physical nomadic community. Speaking to a lover, she laments, “…bandaged in your bed, I found only the most fragile / of relics … / their insides wildfire as they kilned your voice / into an old tree’s remembrances of lightning, that I am here / that my just here-ness counts, and the seas / I have crossed through rain / are not my sole dwelling” (p. 21). I think it is in her relationship with the Other that the tension animating the nomad becomes most apparent. While it is her very constitution to wander, she must ask for land, the warmth of another’s flesh, in which to rest.

So back to the original question – why did I choose the nomad? I think because she is the closest articulation to what I understand the problem of emplacement and embodiment to be for people who are molding a life out of dislocation, violation, disappearance. And not only biological/material life, but a life of “holy things”. A sacred life.

AVAILABLE NOW! www.dinahpress.com.

The nomad is not dealing only with movement in and out of space. She is also negotiating her body as a space to live in and co-exist with. The body not as home, but as tent, hotel room, rented basement with the landlord living upstairs. How does one carry such a body into strange territories? How does one meet, contest or reconcile with places through that body? And how do places enter that body? Ravage it? Sustain it? I think these were the questions that concerned me most. Certainly many concrete aspects of the nomad draw on my personal experiences, but the heart of her, the thing that makes her not necessarily real, but true, is composed of braids of revelation that belong to us all. And one of the most valuable lessons I learned in the writing of this book is that the poetic craft demands us, as poets, to offer our experiences not as truth, but in pursuit of truth. One moment of this in “ode to sambal,” which describes the circumstances and physics of consuming this amazing Indonesian staple: “…our tongues swell and words forsake us / until we are leaves again scraping the blue ends / of God’s feet. for an hour or two / you hack at intestines, burning / thicker than the quiet / we have knotted into bodies” (p. 10).

I believe the nomad has an important role in our world today. A world that is contending with the deepening colonization of indigenous lands; proliferating and unending military occupations; the mass displacement of peoples due to war, famines, political and social persecution; reckless yet brutally calculated destruction of nature, habitats and human communities by the elite capitalist class; the expanding Gargantuan machines of prison, police, detention, torture, surveillance; violence and hatred perpetrated against women, children, indigenous people, people of color, workers, migrants, poor people, disabled people, queer, trans, intersexed people, and so many others whose beauty, voices, pain fall though the cracks of identity politics. And of course, the throbbing, restless life we continue to enact, defend, reach toward – as individuals/families/communities, however make-shift – in spite and because of all of this.

The nomad offers neither anthem nor solution. She offers a kind of spirit that is working at life in these times. While the poems in the book addresses various issues, one persistent area of intervention is around the idea of home. The desire to belong, to be secure (which animates so much of the global symptoms we witness and are complicit in) so easily lends itself to fear and violence, to the directive “I need” / “I am entitled to” rather than “I ask.” I am reminded of a line by Rainer Maria Rilke, “Killing is one form of our wandering sorrow…” (from Sonnets to Orpheus). And I believe the nomad, by virtue of what she is and what she needs to survive, is constantly learning to ask. To combine many roots into a roof, which she counts on rain, or will, to dissemble. Among many things, she is a renouncement of permanence. A song sturdy enough to dwell in.

November 23, 2012

5 Reasons Why Despite Pronouncements to the Contrary, Poetry Just Won’t Die

I write the poems that bite back. -Neruda Perdomo at 8 years old.

A few weeks ago I had this rather unpleasant confrontation with another writer of color in cyberspace because I disagreed vehemently with their announcement that poetry is dead and poets are cliquish, etc. (well, not so much the latter; poets certainly have the capacity to be exclusive – we’re human and like other humans we’re not obligated to be friends with people we don’t like or respect though we certainly have a responsibility to listen and advocate for under-represented voices).

Of course the irony is that poetry ain’t mad that some people believe or want it dead. Poetry has room for any of us to question its existence (I would add precisely because it is a living art!). And while I do not usually feel personally offended by critiques of poetry, or of poets, even – hell I engage in both those exercises all the time – a statement like that by someone I felt an affinity to felt like a kick to the gut, because we were both part of a community of writers of color whose basic premises were a) respect for each other’s projects and b) common ground as people who have experienced systemic silencing. As a poet in that community, I felt attacked and betrayed. The statement didn’t come off as a “critique”, but as a denouncement.

This experience galvanized me to pen the reasons why I believe poetry remains a vital, necessary and relevant aspect of human experience, especially in our contemporary world. I took inspiration from Neruda, the son of my teacher and brilliant poet Willie Perdomo, to well, “bite back”. So here’s my list of why I believe poetry is going to outlive us all -

1. Poetry asks us to be curious and positions us as investigators of life. Each problem, question, emotion, desire, doubt we confront and navigate in our lives is the heart of a poem, of many poems. To explore them, to give them a body, poets search for materials and deploy various strategies to offer a response. Not an answer. Not a solution. As form of engagement, poetry works to challenge our assumptions of what we think we know about our world, ourselves, each other. It trains us to be close and critical readers of our own perceptions, to re-arrange their component parts into alternate, diverse, at times diverging and often surprising, possibilities. I think the most succinct way to put it is simply that poetry teaches us wonder and exercises our visionary capacities as we grapple with what it means to live, to continue. This is why Audre Lorde wrote that, “poetry is not a luxury,” especially for bodies and subjectivities that have been oppressed, criminalized, stigmatized, broken.

2. Poetry is an emotional and spiritual endeavor. Poets draw both on abstract and concrete constructs as materials for poems – sensations, memories, myths, history, news, metaphysical concepts, etc. How we choose to arrange them in response to a particular problem creates pathways that can either reveal or obstruct emotional/spiritual truth. Speaking on race as a social construct a couple months ago at Rutgers-Camden, Michael Eric Dyson remarked that, “Just because it ain’t real doesn’t mean it ain’t true.” I believe this observation is applicable here as well. Poetry is not a copy of what we perceive. It’s a process of unraveling what we perceive to illuminate what it is in a scene, an image, an event, a character, a sound, that moves us. It is a quest to come closer to ourselves and experience the power, which – in spite of incredible violence and disciplinary measures applied by those with the means and intent to deprive, fragment and alienate us from ourselves – allows us to experience our own abundance and transformation.

3. Poetry rewards us with revelation. Surrendering to the uncertainty and murk of the blank page can lead us to unexpected places. Because the blank page is not empty. When I come to it, I experience it more as a blizzard, and language is the stick I am using to gauge my relative position within that chaos. And I can’t even really define what I am after once I set out because it is not necessarily something recognizable. I just know when I reach that ecstasy of arrival – of being face to face, for a moment, with what is unspeakable in my soul, of touching a truth which escapes, exceeds language and which, yet, I live on. I believe the thirst for revelation is what compels all our efforts at communication. It expands our hope for empathy, our capacity to remember and to be, as Meena Alexander puts it, “reconciled to the world we live in” (and by reconciliation meaning it helps us claim our portion in the world, to be implicated in it and not complacent of the injustices we suffer, witness and participate in); it endows us with greater choice on how to be. The most ardent, unapologetic example of poetry as revelation, poet as prophet, for me is Joy Harjo, who I am blessed to call a mentor.

4. Poetry is an inherently social practice that draws strength from solitude. It might seem cliche, but it bears repeating that poetry is written for, by and to somebody. It is that part of my spirit that cannot be captured in narrative, theory, or history; it is the rhythms, colors, waves of what Yusef Komunyaaka calls, “the eminent silence,” within me reaching out to and attempting to glimpse yours. Because that silence, like the blank page, is not empty. It is a reckoning. It is many reckonings. Stanley Kunitz wrote of poetry that it is “a sign of the inviolable self consolidated against the enemies within and without that would corrupt or destroy human pride and dignity.” I love this definition because while I make no assumptions of you, reader, I certainly have experienced my most persistent demons to thrive within myself, even if they were birthed and forced into my psyche initially through the actions of others. In poetry, the distinction between self and other simultaneously blurs and clarifies; the body houses what it travels through.

5. Poetry is for everybody. Not everyone writes poetry, but poetry matters for all of us. Our oldest historical memories that have transmitted to us the tensions and densities of what it has meant to be human (incompletely of course because of the widespread exclusion of women), come largely from poets whether in text (Homer, Rumi, Sappho, etc.) or in the oral traditions inherited and adapted from generation to generation (for instance, the wayang kulit tradition in my country). Learning how to read and appreciate poetry is learning how to read and appreciate our soul – that song in us which is shaped by and yet transcends history. If today much of poetry has been appropriated by academic institutions – in terms of recognition (i.e. credentialism), copyright, readership – let us not allow ourselves to be deceived or deprived of its affirmation of life. I see and hear it in the young people I’ve worked with and have been – struggling with loss, violence, grief beyond their years – whose impulse to cry, “I exist!” emerges in poetry. I am in correspondence with a young man living in a refugee camp in Malawi and what do we send each other? Poems. As he put it in one of his letters, “Poetry is just a good companion to me, she’s the one I feel much comfortable to express my feelings to, way of my life!!” Poetry is ours to make and nourish each other with. It is what history cannot break in and out of us.

So. I understand that poems written by people who do not reflect us can be alienating. And poets can act the fool. But for every poem we claim has nothing to offer us, there are hundreds that will cry with us in our darkest hours and give succor to those salvaged parts of us. For every poet that acts the fool, there are those we can return to again and again when we are friendless, motherless, childless, lost (these just a few of mine that seem to either reside permanently on my desk or are constantly getting pulled off the shelf) -

Joy Harjo How We Became Human

Mahmoud Darwish The Butterfly’s Burden

Derek Walcott The Bounty

Rainer Maria Rilke Uncollected Poems

Raul Zurita INRI

Audre Lorde Black Unicorn

Suheir Hammad breaking poems

Chris Abani Sanctificum

Federico Garcia Lorca Poet in New York

Agha Shahid Ali Rooms are Never Finished

Jimmy Santiago Baca Martin & Meditations on the South Valley

Patrick Rosal Boneshepherds

Stanley Kunitz Passing Through

Willie Perdomo Smoking Lovely

Philip Levine The Simple Truth

Cornelius Eady The Gathering of My Name

Aracelis Girmay Kingdom Animalia

Nathaniel Mackey What Said Serif

Barbara Jane Reyes Diwata

Natasha Trethewey Native Guard

Ross Gay Against Which

Eavan Boland Domestic Violence

Yusef Komunyakaa Neon Vernacular

June Jordan Kissing God Goodbye

Nikki Finney Head Off and Split

Martin Espada The Republic of Poetry

Samuel Hazo Silence Spoken Here

…and recently, a gift from my husband (and favorite poet, Seve Torres), Stuart Dybek’s Streets in Their Own Ink, which is pure luminosity.

And perhaps this is the best defense at the end of the day, for why poetry matters – in that it needs none. It is bigger than all of us poets and our reasons, though it is certainly useful once in a while to have reminders why it is we are committed to this work, which so often provides little to no material reciprocity in a world where our economic existence as working-poor folks, women, people of color, etc. has been and is becoming increasingly tenuous. A world where poetry is necessary as bread. Hope this post encourages you to take a bite.

light. one love. salaam.

November 20, 2012

Gaza Gaze (in)

after Suheir Hammad

Gaza is eye

heroic bloodied

light unblinking ether

Gaza is mouth

chewed oceanic

scream’s muscled thorn

Gaza is knees

river rubbled

morning clouds shear

Gaza is wings’

beat beneath

gauze of clean picked ribs

Gaza is thrown

tent of spines

over splinter singing

rock

firmament

forehead

Salvage like belly

fixture of sleep album

of feathers once self

Gaza is Suheir writing

I am damaged beyond

recovery is cold sweat

all night my sister

reporting three Chinese

at the solidarity rally

herself included

bruise I want to knit all

my bones around

Gaza. Is not never

mine what makes me

human incapable

to stop loving is wound

lineage my son

learning to spell knife

toward

challenge

breath

Palestine

—————————————————————————————–

*The list of italicized words at the end is exactly, in that order, what I asked my son Paul to practice spelling yesterday evening, hours before receiving Suheir’s poem. And I understood something: even language becomes bone and breaks in the gaze of Gaza.