Kristene Perron's Blog, page 4

April 15, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Just Results

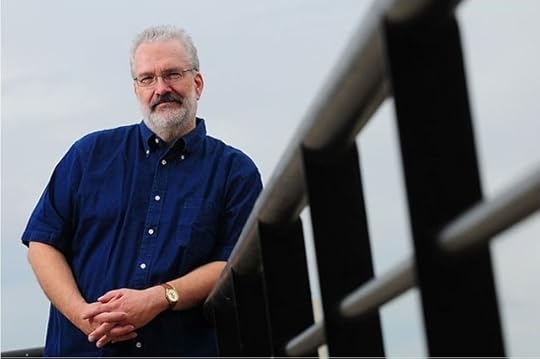

It can be easy to see only the negative connotations of culture clash–fear, hatred, violence–but are there times when our cultural differences cease to matter? Times when our differences are beneficial? Today’s guest, author Alistair Kimble, has some answers to those questions and much more.

“I never went in for embroidery, just results.” ~ Major John Reisman, The Dirty Dozen

What I’m writing about today is culture clash. When I first received the topic, Boy George fronting The Clash cluttered my eyes and ears with discordant images and sounds. And while I don’t think Boy George and The Clash would have ever worked, the truth is, well, maybe they would have found a way if they had been forced to work together. Look at how successful the collaboration between Metallica and Lou Reed was–uh, never mind. But if you’re a masochist, look it up some time, the project was called Lulu.

But I’d rather write about the positive side of culture clashes. So, onward and upward. I’ve worked many different jobs since I was 15 years old and now, looking back at them at the ripe old age of 45, I wouldn’t have changed a thing since it’s all been material for my fiction. All the good times, bad times, arguments, happy hours, work trips, and getting to know a vast number of people who are not at all like me have all provided a life time of storytelling material.

Working with others, whether it be a mom and pop shop or let’s say a military force, is often a clash of cultures. I enlisted in the United States Navy back in 1993 as a 23 year old with a couple years of college under his belt. What does that have to do with culture clash? Plenty.

I enlisted, which meant I was going to be joining others who also hadn’t completed college, or even started college, or perhaps had no desire to go to college. But here is the clash, which is actually something the military gets right–taking men and women from diverse backgrounds, shoving them together, and forcing them to become a functioning and successful unit before graduating from boot camp.

As a 23 year old, I wasn’t the oldest in my boot camp company, but was close. The age range in my company was 17 to 26, which is quite a gap, and that alone can be a culture clash. There were guys (and there were also entire companies of women, even back in 1993) from all over the country and from all sorts of backgrounds. Some joined to escape bad situations and others joined to finish their education, while some sought the Navy as a career and others simply as a job until they figured out what they really wanted to do with their lives.

The first couple of weeks locked up within the confines of the Navy base housing the boot camp were especially rough, and understandably so: When a bunch of mostly immature males are tossed together the only absolute result is chaos. The first week the barracks were a mess, as if a gym locker full of sweaty clothes exploded on a daily basis. We spent hours simply organizing and cleaning so when the company commander kicked opened the door we wouldn’t be marched and/or exercised to death. Natural leaders within the company emerged and eventually the barracks resembled a livable space.

I’m happy to say that there were no race issues, class issues, education level issues, etc. Don’t get me wrong, when that many young testosterone laden men are thrown together there are bound to be some scuffles, but they were few and those were motivated by stress, fatigue, and well, there are times you just don’t like a person. The first few days, maybe even the first couple of weeks had guys of similar backgrounds hanging out, but once past the veneer we all found that the cultural differences didn’t mean a whole lot, we all pretty much wanted the same things, but most of all, we all wanted to conquer boot camp.

Eventually the differences melted, and the company realized working together, identifying individual strengths, and leveraging those strengths would overcome the problems thrown at us by the company commanders. Problems like middle of the night inspections, random physical fitness drills, and staying up to the wee hours despite the lights off policy simply to make sure everyone in the company would pass the barracks inspection the next day. It reminded me of the old comedy starring Bill Murray, Stripes (oh man, just writing that made me feel old). Anyway, the group of misfits in Stripes had to come together to get out of boot camp, but with hilarious effect. And then there is The Dirty Dozen–a different group of misfits, but they too, overcome, but–oh yeah, most of them died in the process. Anyway…both of those films were quite opposite of my experience at boot camp. Moving away from the military for a moment, we can take a television show like The Office and that group of people is beyond culture clash, but still somehow manage to sell paper products.

I think if you toss any group of people together (face to face–not an internet group or Facebook thingie or whatever) and they need to overcome an obstacle or achieve a goal they’ll put aside their differences and get it done. By the way, I don’t count politicians as a group of people you can toss together and expect anything great–that group is the exception to the toss together and work things out idea I’m putting forth here.

The bottom line is that there were 60 or so men in my company who did not know one another when we were marched from the processing center to the barracks, and it was scary and disorganized and messy. But a few months later we had transformed from 60 strangers all a unique culture of their own into a group of individuals who had learned how to work together.

A long time ago Alistair Kimble enlisted in the Navy and performed search-and-rescue missions while dangling from a helicopter. He now works as a Special Agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and somehow finds time to write. Iron Angels, an urban fantasy novel with police procedural bones, co-written with Eric Flint, will be published by Baen Books. His short fiction has appeared in the Fantastic Detectives Issue of the Fiction River Anthology series and Eric Flint’s Grantville Gazette.

A long time ago Alistair Kimble enlisted in the Navy and performed search-and-rescue missions while dangling from a helicopter. He now works as a Special Agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and somehow finds time to write. Iron Angels, an urban fantasy novel with police procedural bones, co-written with Eric Flint, will be published by Baen Books. His short fiction has appeared in the Fantastic Detectives Issue of the Fiction River Anthology series and Eric Flint’s Grantville Gazette.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

April 13, 2015

Culture and Conflict: The Morality of Culture

In an attempt to accept diversity, we will often defend behaviour we find strange or unacceptable as a difference of culture. And while it’s generally good to embrace cultural differences, is there a line where culture ceases to be a valid defense? Today’s guest blogger, author Nathan Elberg, discusses culture and morality.

Some things are disgusting. Pedophilia for instance is considered intolerable, despite its being promoted by writers such as William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. Their advocacy for evil did nothing to harm their positions as cultural icons. There are grey areas as to what constitutes a child. Loretta Lynn, the famous country singer got married when she was fifteen. Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam, consummated his marriage to Aisha when she was nine, setting the gold standard for Muslims.

Some things are disgusting. Pedophilia for instance is considered intolerable, despite its being promoted by writers such as William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. Their advocacy for evil did nothing to harm their positions as cultural icons. There are grey areas as to what constitutes a child. Loretta Lynn, the famous country singer got married when she was fifteen. Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam, consummated his marriage to Aisha when she was nine, setting the gold standard for Muslims.

Sex with animals is also considered impolite, but all the videos of Hamas and ISIS terrorists having sex with goats has not diminished their stature as liberation warriors, as cultural icons.

Sex with non-humans is disgusting, but there are grey areas as to species. In 2008, the Spanish government passed a resolution according human rights to apes. In the USA, PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) compare Jews and chickens, saying both suffered a holocaust. In Indonesia, a teenager was forced to marry a cow he had been caught having sex with (the bride was then drowned).

There are tribal hunters who try to seduce animals, but not for the sake of copulation. Certain Siberian hunters will mimic an elk, try to make themselves appear as suitable mates, to encourage the animal to be available for killing. There’s a danger to this, though. Sometimes the seduction can go the wrong way, and the hunter lose his human status. In such a case the human ends up living in the elk’s village, or, if things go really wrong, being killed by the elk.

For some Amazonian Natives, animals are people, or see themselves as persons. The manifest forms of each species is merely an envelope, a clothing which conceals an internal human form, usually only visible to the eyes of fellow members of that species, or to shamans. This is similar to a concept in Jewish mysticism, that skin and clothing make us appear to be what we are not, revealing what we want the world to know about us; revealing that something is being concealed.

These are deep, beautiful and mysterious thoughts. They give the lie to the idea that all people are essentially the same, share the common way of understanding and responding to the world. Do these ideas legitimate sex with elk or goats, with young girls or boys? If you’re even considering that thought, then you’ve missed the point. A person with no values has no foundation, no perspective from which to understand another’s values. You need a moral compass to navigate culture.

Nathan Elberg has hunted and trapped with Indians and Eskimos, studied folklore, warfare, cannibalism, shamanism, Kabbalah, primitive art, and communications among other things. All these form part of the Quantum Cannibals world. He is doing a doctorate on the subject of popular beliefs in science and Judaism, is a member of SF Canada, and the Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction Association. He has just launched Quantum Cannibals, a website and novel about science, progress, and culture.

Nathan Elberg has hunted and trapped with Indians and Eskimos, studied folklore, warfare, cannibalism, shamanism, Kabbalah, primitive art, and communications among other things. All these form part of the Quantum Cannibals world. He is doing a doctorate on the subject of popular beliefs in science and Judaism, is a member of SF Canada, and the Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction Association. He has just launched Quantum Cannibals, a website and novel about science, progress, and culture.

Nathan’s recent short stories include:

Dancing With Whiskey Jack; Bewildering Stories (estimated publication late 2013)

Sticks, Stones, and Monsters; Bewildering Stories

The Ways of the Goat; Portals print anthology, ed. Dorothy Davies; estimated publication late 2013.

A Matter of Trust; The Lorelei Signal

The Fire Snake Constellation; Roar and Thunder

Iron Will, Broken Fingers; Shadows of the Mind anthology, ed. L. J. Gastineau

Sitting in a Tipi, Waiting for a Truck; Scholars & Rogues Literary Journal

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

April 10, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Literature and Culture Clash

Most stories, fiction or non-fiction, contain some kind of conflict–cultural or otherwise–but what about the actual medium itself? Author Nowick Gray considers the culture clash between corporate media and literature and what that means to society.

In my recently published novel of the Arctic, Hunter’s Daughter (Five Rivers, 2015) the very basis of the plot, themes and character development is the clash of cultures. The era depicted (1964) is one of Inuit transition from traditional life on the land into settlements; and the story’s tension is driven by pressure from the bureaucracy of the South to conclude justice on its terms. While the clash of cultures is at the forefront in such a story, I want to delve further here into a more radical perspective of cultural confrontation between literature and mainstream society.

In my recently published novel of the Arctic, Hunter’s Daughter (Five Rivers, 2015) the very basis of the plot, themes and character development is the clash of cultures. The era depicted (1964) is one of Inuit transition from traditional life on the land into settlements; and the story’s tension is driven by pressure from the bureaucracy of the South to conclude justice on its terms. While the clash of cultures is at the forefront in such a story, I want to delve further here into a more radical perspective of cultural confrontation between literature and mainstream society.

As editor of the online Alternative Culture Magazine, I once argued that literature, in a way, by definition is “alternative.” That is, it is designed to get the reader to think and/or feel deeply, to access unconscious associations and versions of reality, different species of truth. If not in direct contradiction to the stories peddled to us as fact by the mainstream news, at least creative narratives offer alternative perspectives.

In an age where, by virtue of the so-called alternative news channels on the Internet, we come to know, for a fact, that major news outlets are owned by a half-dozen corporate entities, and that for decades now these newspapers, magazines, networks and movie studios have been infiltrated and imposed upon to offer versions of important stories that are vetted or created by the CIA (in the US, at least) to conform to the operative script for so-called national security. Such collusion is also well documented in the case of the BBC. Even such supposedly liberal papers as The New York Times or the Guardian have to satisfy their megacorporate advertisers. (I haven’t done my homework on Canadian media control and influence but it surely plays in the same league, if not in the same ballpark.) The point here is that there are two cultures warring for control of our minds: mass media programming, and the one-on-one experience of the writer and reader.

In the shallow world of popular commercial media (call it fiction), the plots are linear, horizontal, ephemeral, chaotic. Contrast the world of the literate novel or creative nonfiction, where the effect is more of depth psychology, of archetypes and synchronicities, of resonance and innuendo. Where there is nothing claimed outright in bald, bold terms (like advertising or the latest headlines of violence), there is no point in counter-claim and disputation; the work stands alone, interpenetrating the felt (and thus uncontested) experience of the reader. Evidence accumulates through the texted encounter; and unlike at a court proceeding, the verdict here need not be unanimous, nor handed down by any judge, nor by a committee of one’s peers, nor even conclusive to a single simple outcome. The experience gestates as a whole, generating further truths percolating through the reader’s consciousness over time. The associations are not tied to chains of corroboration; they link as our brains discover. Meanings surface not as polls of policy debate, but as the weight of a breath, the knowing of action at the next opportunity.

This largely hidden clash of cultures surfaces when the worldly empire of ideas feels so threatened by the revolution of experienced truth, that it feels it must burn books, or censor them, imprison its writers and threaten their publishers. Otherwise, in a freer society where at least we can choose our sources of information and entertainment, it is our own choice and responsibility, which culture to be a part of. Will we parrot the news and opinions piped into the ears of millions wholesale by CBC or CBS, eat and regurgitate like fast food, empty calories—or browse selectively, read thoughtfully, question the authority and agenda of the writer and producer, and digest in harmony with our own internal ecosystem of moral enzymes; trusting our own sensors of taste, reserving our own judgment of quality?

The foregoing polemic notwithstanding, it’s a tricky business to confront the dominant culture head on, even at the height of one’s creative powers. Satire, of course, is an effective weapon/tool (witness Jonathan Swift, Joseph Heller, Tom Wolfe, Don DeLillo, Margaret Atwood, Dave Eggers, to name a few). Or, one can back away from the fray in a more ironic, purportedly self-effacing fashion: I’m thinking of the latest novel by British writer Tom McCarthy, Satin Island:

It’s not my intention, here, to write about the Koob-Sassen Project: to give an exegesis, overview, or whatever, of it. There are legal reasons for this:…stipulations protecting commercial, governmental and the level that comes one above that confidentiality; interdictions on virtually all types of disclosure. And anyhow, even if there weren’t, would you actually want to hear about it? It is, it strikes me, in the general scale of things, a pretty boring subject. Don’t get me wrong: the Project was important. It will have had direct effects on you; in fact, there’s probably not a single area of your daily life that it hasn’t, in some way or other, touched on, penetrated, changed; although you probably don’t know this. Not that it was secret. Things like that don’t need to be. They creep under the radar by being boring. And complex….Perhaps all projects nowadays are like that—equally boring, equally inscrutable….would this, in any way, illuminate the Whole? I doubt it. (2.1)

Yet here is the genius of art—that by skirting an issue which invariably is boring or disempowering when tackled head on, and couching it just so—in the sensibility of a real or fictional narrator, a human guide with a heart we can feel close to our own—it becomes appreciated, integrated, understood. In the reading experience we make that transition from the culture described, to the culture of the describer, the witness. And the larger truth we thus perceive sets us free.

Nowick Gray has published a wide variety of fiction and nonfiction, most recently the mystery novel Hunter’s Daughter (Five Rivers, 2015). Much of Nowick’s writing draws from his two decades homesteading in the interior mountains of British Columbia. Other adventures include teaching for three years in Quebec Inuit villages, and indulging a lasting passion for West African drumming. Nowick currently works as a freelance copy editor and makes his home in Victoria, BC, with winter travels in warmer locations. Connect with Nowick via his website, nowickgray.com, or via Twitter or Facebook.

Nowick Gray has published a wide variety of fiction and nonfiction, most recently the mystery novel Hunter’s Daughter (Five Rivers, 2015). Much of Nowick’s writing draws from his two decades homesteading in the interior mountains of British Columbia. Other adventures include teaching for three years in Quebec Inuit villages, and indulging a lasting passion for West African drumming. Nowick currently works as a freelance copy editor and makes his home in Victoria, BC, with winter travels in warmer locations. Connect with Nowick via his website, nowickgray.com, or via Twitter or Facebook.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

April 9, 2015

Kristene’s Creative Ink Festival Schedule

We interrupt our regularly scheduled blog series to tell you where you can find Kristene Perron on April 25 at the Creative Ink Festival…

Hi everyone. I’m thrilled to be participating in the very first Creative Ink Festival in Vancouver, BC on April 25th! This year a preview for the big event, which will be a weekend long festival for writers, readers, artists, and fans of genre fiction. You can blame firecracker Sandra Wickham for all this fun and frivolity as this festival is her creation.

There’s a good chance you’ll spot me wandering around, being my usual chatty self, but here are the events I’m scheduled for:

10-11am – Blue Pencil Session

This is your opportunity to sit down with me (or other industry professionals) for fifteen minutes, to share your work and receive immediate feedback. Bring three pages of your best work (double-spaced). I will read your work and give you my input. You may also want to bring your questions about troubles you’re having with the piece. You need to sign up for this in advance. Email sandrawickham@live.ca to book your session!

2pm – Intro to Self-Publishing

So you’ve heard self-publishing is the best/worst thing to happen to writing since Gutenberg’s printing press and you’re wondering if it’s right for you? In this one hour, hands-on workshop, I will dispel the myths, exposes the scams, and shows what it takes to self-publish successfully. From first draft to first sale, you’ll learn the questions you’ll need to ask and the tools you’ll need to determine your publishing path. Topics include: * Timelines and budget * DIY vs self-publishing services * Formatting, editing, cover and interior design * Choosing the best publishing option * Self-publishing resource.

5pm – How to Market Yourself Panel: Danika Dinsmore, Peter Darbyshire, Kristene Perron, JP McLean

Whether you’re a writer or artist, indie or traditionally published, marketing yourself is vital to a successful career. What are the best tools out for getting your product out there? What should be avoided? What should your marketing budget look like? Are there any unique ideas left?

You can read about all the amazing programming here and you can plan your day here.

I’ll have copies of Warpworld Vol. 1, 2 and 3 on hand for sale. And you will find a special Warpworld goodie in your festival “swag bag”.

If you see me, make sure to say Hi, or even better…

Blood for water

~ Kristene

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

April 8, 2015

Culture and Conflict: What the Okal Rel Saga is All About

When we put out the call for guest bloggers, Lynda Williams was a natural fit. Her Okal Rel universe is fraught with culture clash. In this post, she talks about the many sources of cultural conflict in her books.

Readers who like their culture clash played out through characters where no one is 100% right about anything, will enjoy spending time in the Okal Rel Universe.

Imagine politically sophisticated high-tech invaders clashing with biologically empowered tribal leaders, known as Sevolites, who are, themselves, the advanced technology. Or a conquering Sevolite warrior who can’t understand why “take me to you leader” means a planetary referendum for AI-enabled egalitarians from Rire. And these are just the political teasers.

Sexual politics between the neo-Victorian Demish and the free-flying Vrellish generates humor and drama in every book. But no group is without its own kind of norms. Instead, conflicting standards duke it out in the wider Sevolite cultural context of Okal Rel, in which genetic capital is tied to economics through a spectrum of religious beliefs about the rebirth of souls.

The agnostic humanist culture of Rire, founded on egalitarian ideals, has yet another set of rule governing sexual relationships and, in particular, adult responsibilities for raising children. Reetions are horrified by Sevolite use of infants as political pawns. But then, most of us would be as well.

Perhaps the most controversial question of nature vs. nurture in the ORU is just how different a bio-engineered Sevolite is, biologically, from natural humans. Does this entitles them to behave differently? If so, to what extent? At what point should multicultural acceptance give way to war, again? Because the differences concerned aren’t trivial.

For example, Vrellish women have as much testosterone in their blood as Vrellish men. And the gentle sensibilities of Golden Demish rest on a genetic predisposition that never had to stand the test of viability in the evolutionary sense. The notion there is any validity to racial stereotyping offends moral thinkers from Rire, but Reetions do not hesitate to view themselves as culturally superior – even though the lack of personal privacy in their transparent society rankles on most Sevolites. And what Sevolites consider a legal means of resolving their differences through Sword Law is murder, pure and simple, to someone from Rire.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and world mistress of the expanding Okal Rel Universe. She will be appearing April 25, 2015 at the first Creative Ink Festival event in Burnaby, B.C. http://www.sandrawickham.com/creativeinkfestival/ and publishes at http://facebook.com/relskim By day, Lynda works for Simon Fraser University and teaches part-time for BCIT.

Lynda Williams is the author of the ten-novel Okal Rel Saga and world mistress of the expanding Okal Rel Universe. She will be appearing April 25, 2015 at the first Creative Ink Festival event in Burnaby, B.C. http://www.sandrawickham.com/creativeinkfestival/ and publishes at http://facebook.com/relskim By day, Lynda works for Simon Fraser University and teaches part-time for BCIT.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

April 2, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Permission to Speak Freely?

When Josh and I put out the call for guest bloggers for this series, we wanted to hear from people with real life culture clash experiences. Former US Marine Garvin Anders has those experiences in spades. In a candid post, he discusses how tricky communication can be between sub-cultures within cultures.

Culture clash can happen in a lot of different ways and I’ve experienced most of them, if I may be excused some vanity. I am a hearing child of deaf parents. I grew up in Oklahoma but live in Arizona. I am a Marine surrounded by civilians. I am a Christian whose closest friends are atheists. Thanks to the Marine Corps, I’ve experienced Japanese and Arabic cultures in a pretty up close and personal way (there is little more personal than being shot at, I think). In some ways it’s hard for me to pick up singular incidents of cultural conflict because, frankly, dealing with different cultures is a norm for me.

In Deaf culture, for example, it’s perfectly normal to be blunt to the point of what the rest of the world would consider rudeness. When I arrived back home for Christmas after being away for two years, my mother’s first words to me were, “You gained a lot of weight!” It’s also normal to tell someone all sorts of things when you first meet them. I’ve had deaf people tell me their entire life story after knowing them for only fifteen minutes. This bluntness makes sense when you realize that, if you’re deaf, you don’t get to spend a lot of time with people just like you. You might only see another deaf person a couple of times a month. In those rare meetings, you have to make up for lost time. Public school trained those habits right out of me. It also trained me to swing low and hard. I still dislike having conversations where I’m not looking at the person or they’re not looking at me. When I’m having a Skype conversation? I’m staring at the screen as a substitute a lot of the time.

Those culture clashes I’m used to. Those are my life. The real nasty ones? Those are the ones that sneak up on you. When you think you’re not around any cultural divides.

There’s also the clashes that come when you were raised in a religious household and still maintain the faith. Even if the vast majority of your friends really don’t. I brought a conversation with several of my friends to a screeching halt with several of my friends because I told them I couldn’t really have anything to do with Tarot Cards or Ouija boards. Not because I believe there’s anything to them but, to be blunt, they’re symbolic of a belief system that a Christian, or at least the kind of Christian I am, shouldn’t have much to do with. Don’t get me wrong, it’s perfectly fine for other people to use them if they like, but I really can’t. My friends simply could not grasp this explanation. They knew that the cards and the boards and all that didn’t work. Since they didn’t work, there simply couldn’t be any issues in messing around with them. That I could have reasons that don’t have anything to do with my belief in their ability to tell the future or contact the dead (I don’t believe in that for the record), seemed to fly right over their heads no matter how I struggled to explain it. In the end, I finally just said I don’t mess with them for my parents’ sakes, which while not anywhere near the primary reason was close enough to true, and convenient enough an explanation to make everyone happy.

For awhile after the Marines I had a job cleaning theaters. I learned to hate it because… Well let’s just say most of my fellow employees there share my feelings. I worked there because I was in school and needed to pay rent in the summer (the GI Bill is nowhere near as magnificent as you think). The theater was having a rough spot, money was coming in but people were quitting and it was hard to keep anyone. Well, harder than usual. For some reason a manager got it in her head to ask me what I thought. I did something stupid. I lapsed into Marine. I asked if I could speak freely and, when told yes, I proceeded to be honest and forthright and frankly I did some bitching. Because frankly the management was part of the problem.

Now, in the Marine Corps (and other armed services), bitching is a right of enlisted men. There are rules of course—don’t bitch in front of outsiders; bitch up not down; do your fucking job first, bitch second. Additionally, let me cover ‘permission to speak freely’. It’s a phrase often quoted in movies but not so often said (I served for 4 years, I think I used it… Twice? Not more than that). It’s a bit of a loaded question. Saying yes means you agree to hear what I have to say and not hold it against me professionally or personally. You can say no, but say no too often and you’ll find yourself with a reputation as someone who cannot be trusted, and units have ways of screwing over their leaders if they want to. In the world of movie theaters “permission to speak freely” doesn’t work like that.

After speaking freely, I was sent home for the day for improper attitude. Luckily one of the newer managers who heard about the conversation the next day was ex-Army and, after a brief discussion with me, he smoothed it over. I still get grumpy about that incident from time to time, though. I mean if you didn’t want to hear what I actually had to say, why did you even bother to ask?

Garvin Anders, born in the 80’s to Deaf Pentecostal ministers, served as a Marine, worked in factories, Walmarts, fast food places and more. He attended ASU until someone was silly enough to give him a BA in Anthropology. He currently works for an insurance company while tutoring ASL and writing strange blog entries.

Garvin Anders, born in the 80’s to Deaf Pentecostal ministers, served as a Marine, worked in factories, Walmarts, fast food places and more. He attended ASU until someone was silly enough to give him a BA in Anthropology. He currently works for an insurance company while tutoring ASL and writing strange blog entries.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

March 30, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Canadian Vs. American Science Fiction

Today’s guest knows his science fiction! Aurora Award winner Robert Runté explains the differences between science fiction from two seemingly similar countries.

Today’s guest knows his science fiction! Aurora Award winner Robert Runté explains the differences between science fiction from two seemingly similar countries.

Most SF writers, editors, publishers, and readers would accept that the SF genre represents something of a different subculture, often at odds with the mainstream literary establishment. Much less recognized, however, are the cultural clashes within the genre. I’ve spent much of the last 35 years talking about the differences between Canadian and American speculative fiction. We tend to think of SF as an American genre, because it often reflects American values and themes, but Canadians write it too, and—unless consciously writing for the American market—their work is likely to reflect their Canadian values.

Here, then, are some of the characteristics that have made Canadian SF distinct from the American version of the genre:

Focus on environment/ nature over man

Back when John W. Campbell was editor of Analog, the typical American hero was an engineer who landed on an alien world, was presented with a problem, fixed it, and made space safe for democracy. Americans believed in progress, technology, and the rightful dominance of Man over Nature.

Canadian SF in the same period tended to the opposite: it was highly skeptical of technology and progress (as in, say, Gotlieb’s Sunburst), and portrayed Nature as dominant over Man. Whenever Man went up against Nature (e.g., Hargreaves “Protected Environment“) Man lost.

[Interestingly enough, as American society started itself to question these values, Canadian SF started to come into vogue. Having already mastered a dark vein of pessimism about the future, Canadian writers enjoyed some traction in the early 1990s. It is difficult to tell if that trends continues, as American writers have increasingly picked up the same themes.]

Setting often plays a more important, even a dominant role, in Canadian SF: e.g., Dave Duncan’s West of January; or Candas Dorsey’s “Sleeping in a Box” where setting is the story. One could argue (as Atwood has) that our focus on environment is because we live in a country where the environment can’t be ignored, but it makes for a slightly different take on SF than a vision based on terraforming.

The (bungling) protagonist as average citizen

American SF tends to feature the hero: a protagonist who is presented with a problem, sets goals to overcome the problem, struggles, and through dint of his own talents, strengths and effort, ultimately wins against the odds. The American hero is therefore an exceptional individual who is worthy of the story because they acted courageously and outsmarted or outfought their antagonist(s). They initiate the action and their own actions determine their success or failure. In brief, the hero is an alpha male, even when cast as female.

The Canadian protagonist, on the other hand, is often just an average guy caught up in events he neither controls nor understands. Canadian protagonists don’t do things so much as have things happen to them. If the Canadian hero has a distinguishing characteristic, it is not that they’re smarter or tougher than other people, it’s that they’re nicer. The story is not about winning or achieving goals so much as about managing to endure, to ‘hang on’. Whatever goals they may have had at the outset, achieving those isn’t usually where the story ends up.

That is, if the protagonist is even involved in the story:

The Uninvolved Observer / Alienated Outsider

Often the Canadian viewpoint character is not whom the story is about at all, but is merely a detached (often wry) observer. He’s not the captain of the starship, he’s the maintenance guy; he’s not the guy abducted by aliens, he’s the neighbour who saw it happen. One could see this as a result of our national inferiority complex: we do not picture ourselves as the adventurers who land on the moon, we’re the supporting roles in the background who provided the Canadarm. The position of detached observer does, however, provide the opportunity for a certain amount of ironic editorializing.

Or, to put it another way, Canadian SF is often written from the point of view of the alienated outsider. Again, this can be traced back to our national sense that whatever is interesting in the world is happening somewhere else. Alienation is, of course, a common enough theme in all of 20th Century literature; and a lot of SF uses the metaphor of the alien to confront readers with the ‘other’. What distinguishes Canadian SF is that it often presents the viewpoint character as the ‘other'; and then makes the astonishing suggestion that being on the outside might be a good thing. Take for example H. A. Hargreaves’ classic and widely reprinted story “Dead To The World” in which our hero finds himself locked out of his apartment, his bank account, and ultimately society because a computer error has listed him as dead. In spite of his hapless efforts to have his existence officially reinstated, he ultimately fails—but discovers instead that he is much better off ‘dead’. As Canadians, we often find ourselves the mere observer of world events dictated by our neighbours to the South; but are often just as happy we’re not involved, glad to remain on the outside, alienated but snidely detached.

Ambiguous Endings

American (mass market) SF tends to have happy endings; British SF is as likely to have unhappy endings; Canadian fiction—you can’t always tell.

The ambiguous Canadian ending flows somewhat naturally from the hero as average citizen: our hero gets caught up in events, hangs on, and gets dropped off more or less at random as the crisis subsides or moves on. Is the hero better or worse off? Hard to say—things are often just different.

Take, for example, Leslie Gadallah’s The Legend of Sarah. No one in the book actually achieves the goals they set out to achieve: Sarah does not get the dark handsome spy to whom she’s attracted; our male protagonist is immediately arrested as a spy and spends the rest of the book in a dungeon; his wife tries to rescue him but breaks into the wrong dungeon; their friends mostly give up on them and go home; and so on. We do get a sort of happy ending, because Sarah and the others come to realize they had the wrong goals when they started out, and things are better the way they ended up. (And also because the bad guys are even more incompetent than our side.) It’s an absolutely brilliant piece of SF, but it a very different approach then the typical American format of the hero triumphing over man, nature and himself to ultimately achieve his goals.

Canadian Themes

Of course, Canadians are interested in writing about themes that matter to Canadians. Take, for example, the archetypal Canadian fantasy, Guy Kay’s Tigana. No Canadian can read Tigana without seeing it as a compelling exploration of the consequences of denying a people their national identity, but that theme may not resonate in the same way or to the same extent with other readers. Of course, one can enjoy the literature of other cultures, but sometimes it is nice to see our one’s own culture reflected in one’s reading.

Why Culture Clash Matters

For Canadian readers, the issue is that it might be worth seeking out Canadian writers to see if perhaps these stories have extra resonance for them. My experience has been that when they discover Canadian content, they tend to say, “Hey, that’s what I’ve been missing!”

For Canadian writers, it’s important to recognize that when American editors, publishers and reviewers reject their work, it may be because it is un-American, rather than unpublishable. Hargreaves sent his stories first to John W. Campbell, who would send back two pages of hand written notes explaining what Hargreaves would have to change to get into Analog, and then say, ‘or, you could just send it as is to Ted Carnel’ (the editor of the British SF magazine, New Worlds) who did in fact publish Hargreaves’ work without change.

For American readers, it may be worthwhile to try something really different, but it helps if one goes in with that expectation: that if a writer has a bungling hero and an ambiguous ending, this might not be a mistake, just very Canadian.

The Fine Print

One of the lessons I’ve learnt over the years is that whenever I make this presentation, I always have to include the following qualifications:

First, these are trends that I (and others) have observed in the past; we are not suggesting this is how Canadians (or Americans) should The critic’s job is to analyze what’s there, not to predict—let alone dictate—what comes next.

Second, any statement about cultural differences is necessarily going to be an overgeneralization: one can always find exceptions to the rule because the conversation is about identifying broad trends, not unbreakable natural laws.

Third, saying that Canadian and American SF tend to be different is not to claim that one is better than the other. Just, you know, different.

Fourth, many Canadians consciously write to sell to the (much larger, better paying!) American mass market, so their books are not always distinguishable from American SF. Indeed, it is often hard to tell if an author is Canadian unless their backcover bio explicitly says so. But when you talk to these authors, most of them confess to having a manuscript in their bottom drawer of which they are secretly proud, but which their American publisher rejected as ‘too Canadian’.

Fifth, with the explosion of vanity self-publishing, online distribution, and the emergence of multiple niche markets (gay paranormal historical romance, for example) the Canadian/American divide is getting a lot blurrier. The legion of first-draft, post-apocalyptic novels posted on online are all going to look pretty much like the Hunger Games movie they’re derived from, no matter which side of the border their teenage authors came from. It remains to be seen whether in the Internet Age, enough Canadian culture survives (or more optimistically, is better able to penetrate and influence the international market) to remain distinguishable.

Robert Runté is Senior Editor at Five Rivers Publishing, an Associate Professor, critic, and reviewer. He has edited over 140 fanzines and SF newsletters, and won three Aurora Awards for his SF criticism; two of the novels he has edited for Five Rivers have also been short listed for the Aurora. He is a freelance development editor / writing coach at SFeditor.ca.

Robert Runté is Senior Editor at Five Rivers Publishing, an Associate Professor, critic, and reviewer. He has edited over 140 fanzines and SF newsletters, and won three Aurora Awards for his SF criticism; two of the novels he has edited for Five Rivers have also been short listed for the Aurora. He is a freelance development editor / writing coach at SFeditor.ca.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

March 26, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Imperfections of Perception

Today’s guest, Tyson Seuret, examines how a simple symbol can divide cultures.

On February 4, 2015, The Huffington Post published an article about an 18-year-old woman in India. She was a woman of passionate creation—a poet, student, and activist for inter-faith collaboration and togetherness. She was considering studying at universities outside of her country of birth, and she was now confronted with the possibility that she must use a nickname, or an alteration of her name to do so.

Why? Because this young woman was named for the Hindi symbol for well-being, prosperity, and goodness of heart that is quite common in India but seen in a very different light for a sizeable population of the world.

Her name is Swastika Jajoo.

As she prepares for study abroad, Swastika Jajoo must face the idea that for many in the world, particularly Western countries for whom World War II is a relatively fresh event in history, the symbol and concept for which she was lovingly named means oppression of others, dividing of people into impersonal camps for their organized mass murder, and horrific levels of brutality and violence. In Ms. Jajoo’s country of birth, the swastika symbol is as common as the Christian cross in most Western countries. The symbol is imprinted on small, personal items to emphasize good luck, prosperity, and goodwill toward others, and given as gifts to symbolize this concept.

So, how did a symbol come to have such contradictory cultural meanings?

Time, distance, and a lack of regular interpersonal contact are the base requirements for a concept to eventually be seen differently by two different peoples. Associations, jokes, and parsings of history are built over time, and eventually can display a wide schism of understanding between cultures.

The swastika’s meaning in its original context has not changed. The German Nazi regime took the symbol and tried to turn it into something belonging only to them, introducing the swastika to people in Western countries as a symbol of small-minded tribalism, of hatred, of separating millions of people into camps for industrialized and inventoried murder. Most people in the Western world had never encountered the symbol before this, and their only context for the swastika was the Nazi regime. Westerners had never seen the symbol used in a context that didn’t involve trying to single out at least one group of people to target for hatred and scapegoating.

From 1939 to 1945, most Indians were perfectly aware that the other half of the world was involved in two large-scale, multi-country wars, but those wars did not directly affect the majority of people in India. Because of this, while Indians could view the misuse of the Hindi symbol for good luck as an insult, it would be difficult for them to see the swastika’s larger connotation in Western countries unless they lived in one of those countries, or spoke regularly, on a personal level, with someone who lived in the West.

This situation is a divide of perception that began less than a century ago, when the Nazis chose to use the swastika as their symbol. Since then, the swastika has grown into the zeitgeist of Western countries as a symbol for everything the Nazi regime represented, on a visceral level, whereas the view of the very same symbol in India hasn’t changed all that much through history. It is tempting to think that in an age of technology, where news spreads quickly and globally, such cultural misunderstandings would cease but, even today, news from distant countries, news that does not directly affect us, seems insignificant. And even when we do consider foreign news, it is through the lens of our own culture.

Conflict of perceptions over the swastika is not simply about how people in Western countries view the symbol versus how people view the symbol in its native country of India. In a larger sense, this conflict shows us the latter vestiges of when humans thought of one another as smaller tribes spread across a vast world. Today, we have populated the world to the extent that tribes of people encounter one another more and more often. Unlike the world of our ancestors, speaking with and understanding the words of someone living in another country is commonplace for many of us.

During the time of the Nazi regime, most people (including most world leaders) thought of different peoples and different nations almost as islands, surrounded by a sea of other peoples. This worldview made blaming specific groups of people for your problems an effective tactic, one that continues to be effective as long as you don’t have regular, meaningful, interpersonal contact with the people being blamed. As long as you can frame interactions with people in other lands as dangerous and unseemly, you will be less willing to speak to someone from a different land and to get their perspective.

In today’s world, many of the barriers between people are dissolving, enabling easy long distance communication between different countries. The Internet is an especially effective platform for this and an example of how cultural understanding grows through communication. In contrast to the cultural division inspired by Ms. Jajoo’s surname, there’s another recent story from Ferguson, Missouri. When issues of police brutality and mistreatment of citizens first came to light, Palestinians tweeted instructions for homemade gas masks to the Ferguson protestors. Two distant and distinct cultures united by the Internet.

The key to reducing cultural conflict is to give people the power and freedom to communicate with one another within an environment that fosters the open exchange of thoughts and ideas. And the best way to encourage this is to take part. Talk with someone from a group of people you don’t know, and get to know them. Learn their hopes and dreams, learn about their family, learn about their personal tragedies, learn about their triumphs, and learn to celebrate them all as experiences that helped this person determine who they are.

And, of course, always be suspicious of those who encourage you to hate and fear entire groups of people. Never forget the imperfections of perception.

Tyson Seuret currently works as computer and network support for a healthcare network, providing support to nurses and doctors to ensure that their workflow is as smooth and trouble-free as possible–though this is more an ideal than a reality. In his free time, Tyson writes very random things, practices chigong, plays video games, and enjoys discussing strange and unordinary things with good friends.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

March 23, 2015

Culture and Conflict: Imagined Realities

In 2014, I had the pleasure of speaking on two panels at VCON with today’s guest. Ron S. Friedman is a Canadian SF/F author but his roots began in Israel.

The Bahai temple in my hometown – Haifa, Israel, where Jews, Arab Christians, Arab Muslims and Bahai co-exist.

Have you ever been in an argument with someone to the point where you realize that you and your counterpart simply have different, unbridgeable point of views? As if each of you grew up in a parallel universe, and that no amount of data and supportive evidence can change the other person’s mind?

If you did, don’t be alarmed. That’s perfectly normal for how a modern Homo-Sapiens’ brain works.

Last summer I flew with my wife and two kids to Israel for a family visit. A few days after we landed, clashes erupted between Israel and the Hamas – a radical Islamic group that controls the Gaza strip.

On the weekend before I flew back to Canada, we went to a family dinner at my in-law’s condo in Holon, a suburb of Tel-Aviv. After we finished dining, we sat at their living room, watched the news, and engaged in conversation, when suddenly we heard the unmistakable sound of air-raid sirens. As was instructed by the Israeli civil-defense authorities, we rushed out of the apartment into the central building’s stairs, which were far from the more dangerous external walls facing Gaza.

There, we met other nervous neighbors. We knew it takes a rocket 90 seconds to fly from Gaza to Tel-Aviv. So we waited. I tried to calm my kids. I told them that we are in no danger, because the Iron Dome missile defense system will intercept the Hamas rocket.

A few seconds later we heard a BOOM! The whole building shook. We looked at each other. A successful interception. The Iron Dome blew up the rocket in mid-air. Soon after, the news announced what we already knew.

A direct hit by a Fajr-5 rocket (175kg warhead) or even by the smaller M-75 (40kg warhead) can destroy a building. But even a successful interception is not without risks. Debris falling from the sky can still wreck a car or kill pedestrians. We were advised to remain indoors for another 10 minutes.

Half an hour later, the same thing happened again. Sirens; rush to the stairs; Boom; wait 10 minutes; done. And later that evening it occurred once more. That night my daughter refused to take a shower. With only 90 seconds warning, she was afraid she would have to run out of the apartment naked.

In short , we had a uniquely interesting family vacation.

During the 2014 Gaza war, the Hamas and the Islamic Jihad fired more than 6,000 rockets and mortar bombs toward Israel. However, in terms of human suffering, the effect on the densely populated Gaza was far worse. More than 2000 Palestinians were killed, many of whom were civilians who had nothing to do with the Hamas or with the fighting.

The Israeli Palestinian conflict, and more so the conflict between Israel and radical Islamic groups such as the Hamas, the Islamic Jihad and the Hezbollah, made me wonder what makes different cultures behave in a way that seems so irrational to someone who grew up in a western society.

I started to look for answers to the following questions: Why do cultures clash? What makes individuals who believe in other ideologies act in a way that makes no sense to me? (For example, the concept of suicide bombing seems alien to me.)

Can you, the reader of this blog, use this knowledge to enhance your writing, and make conflicts feel real?

To answer these questions, I developed a one hour presentation called ‘The Conflict of Writing Conflicts’, which was delivered last year at the When Words Collide Festival, and will be delivered again this year at Calgary’s Comic and Entertainment Expo.

Regrettably, I don’t have enough room here to review the whole presentation or the fascinating source materials. But I would like to share with you the conclusion, in the hopes that it could improve your writing, or at least enhance your understanding of human conflicts.

HERE GOES: Most conflicts occur due to disagreement over imagined reality.

All organisms were evolved to survive. Whenever an animal fights, it does so to increase its own or its offspring’s survival chances. An animal will fight to protect its herd from a threat. It will fight for a territory, for food, water and for the right to mate.

Granted, humans too will fight for all of the above. But the human brain is different than that of other animals. The Human consciousness that appeared about 70,000 years ago allows us to create a fictional reality to explain the world. Many of the very powerful concepts that we take for granted are not real in nature. Concepts such as ideologies, religions, after-life, souls, humans-rights, limited corporations, laws, nationalism, Imperialism and even money. I’m not saying that these fictional concepts do not have a profound impact on the world. They do, but only because we believe in them.

Different cultures believe in different sets of imagined realities. Each culture has a different view on how the world works. Each has its own narrative. And when something happens, individuals from those different cultures view what had just happened based on how they see the world. Then they react to increase their survival chance or even the survival chance of their souls, based on how they see the world.

Back to the Gaza war, most of the Israeli public felt compassion for Palestinian civilian casualties. Having said that, we wanted the IDF to do whatever it took to stop the rockets. As for the Hamas narrative, and why they’d believed they should have fought that war – it’s a complex answer related to their version of religion and their interpretation of history and events that led to the conflict.

RON S. FRIEDMAN’s short stories have appeared in Galaxy’s Edge magazine (edited by Mike Resnick), Daily Science Fiction, Age Of Certainty, and received Honorable Mentions in Writers of the Future Contest in 2011, 2013 and 2014. Ron is Co-editing the Enigma Front anthology, release date – August 2014.

RON S. FRIEDMAN’s short stories have appeared in Galaxy’s Edge magazine (edited by Mike Resnick), Daily Science Fiction, Age Of Certainty, and received Honorable Mentions in Writers of the Future Contest in 2011, 2013 and 2014. Ron is Co-editing the Enigma Front anthology, release date – August 2014.

Winner of the 2013 Aurora Awards – Fan Related category, Ron appeared as a panelist at When Words Collide, Con-version, Calgary Comic & Entertainment Expo and VCON.

Ron is currently working on his second novel. Since 2002 he has lived with his loving wife and two children in Calgary, Alberta.

For more information, visit Ron’s website: https://ronsfriedman.wordpress.com/

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.

March 20, 2015

Culture and Conflict: To Believe or Not To Believe

Our first guest blogger, Aurora Award winning author Sally McBride, considers the question of cultural conflict from a unique perspective–a Canadian liberal atheist married to an American conservative believer.

On paper, my husband and I should never have met, let alone stayed married.

He’s a Texan redneck and proud of it, therefore comes preloaded with a God-fearing, gun-toting, conservative attitude. I’m a Toronto native from an artsy, liberal background, and if that isn’t bad enough (Socialized medicine! The metric system!), I’m also an atheist. Did I mention my hubby went to seminary school and planned to become a priest? Nope? Let me assure you, there was epic culture shock when we married and I moved from Canada to the USA.

The first time I saw him on his knees praying, it was a bit of a turn-on. Kinky, in a Dusty Springfield “Son of a Preacher Man” kind of way. Then I realized he was going to pray every single morning. The kink wore off and the doubts set in.

The relationship firmed up; by my thoughts on religion got wobbly. Was I really an atheist? What about when I toss spilled salt over my shoulder, or raise my arms to the sky and beg for fresh powder on the ski hill? Isn’t that kind of like believing in God? Or at least, the little gods, those of luck and weather. But, the Big Guy? Hmmm.

So, a move from a big city in a trending-secular country to a small town in the western USA happened. Noting that I was surrounded by Americans who loved God and Guns, I learned pretty quickly to stop with the wisecracks about bible-thumpers, or the invisible golden tablets of Mormon. Idaho is awash in Mormons, and most of them are very nice people indeed. Taken individually. One I know is a writer of gay paranormal romance complete with steamy sex scenes, but I think she’s lapsed. I was brought up Anglican, as close to Catholic as a Protestant can get. But everywhere in the States I see houses of worship of all sizes (mostly huge) and most of them are called something non-denominational like “Mountain Meadow Christian Center”, or “Grace Bible Church” or “Word of Life Home Fellowship” and so on. What do those even mean?

From what I can deduce, it’s really enough around here simply to believe in God. To have faith. To hold the certainty in your heart that God, and Jesus too, love and cherish you. Knowing the details of actual, historical religious texts isn’t a prerequisite to bathing in The Lord’s Hot-tub of Love. Oops, there I go being smart-assed again.

Another of my friends, on hearing me speak up and say that I didn’t believe in God, was able to “come out” as a non-believer, though she tends to keep her voice down. Perhaps she felt heartened, or protected, by the presence of another person of the same mindset. I’m getting less and less afraid to state my position as I build a group of friends I can trust not to shun me because of what I think. Because, after all, it’s just what I think. I don’t know.

So maybe I don’t have it figured out yet. But moving to the US and finding myself in a much more religious society than I was used to has made me confront that what-if nagging at the back of my superstitious hind-brain that maybe I should be careful not to piss off something that can squash me like a bug.

This sort of thinking comes out in my writing. After all, doesn’t belief in God imply belief in other supernatural beings? Ghosts, demons, shape-shifters? Several of my stories involve the notion of God, or gods, or the soul, or everlasting life. Religion is interesting. It’s newsworthy. It brings us together, it drives us apart, and it often kills us. What happens after we’re dead? None of us will know till we get there. In the meantime, I believe (if in nothing else) that it’s worthwhile to explore this very human worship-bump.

My short story Szabra’s Souls (Descant Magazine, Fall 2003) is about a young divinity student on a far-off world who must pass a test devised by Szabra, queen of a dead civilization. Szabra’s subjects have passed into another realm, an afterlife. Or is it merely a construct, a waypoint on the journey to true understanding? The test, my young human woman finds, shakes her smug belief to the core.

Of course, writers are most interested in their current work in progress. Mine (among other projects) is a young-adult novel, The Nightingale’s Tooth, set in an alternate medieval France. In this made-up version of Europe, the gods are real, and there are two kinds. One, represented by creatures such as centaurs, gryphons, and the like is the kind everyone can see, if they’re in the right place at the right time. Sometimes one gets captured, or gets involved in human life for its own reasons, or the unfathomable motives of the Great Gods. The Great Gods are the ones you really have to watch out for. Usually up to no good, they have little interest in the welfare of men and women. They are more like emotions made tangible than say, a white guy with a beard, or Gaia, or a stack of turtles. Maybe they’ll turn out to be aliens. I don’t know, I haven’t finished the novel yet. I’m still circling my characters around their needs and fears and desires, and while some characters are pure rationalists, others are controlled by the very Gods they only vaguely perceive.

What does this mean about me and my professed lack of belief? Am I a searcher and just don’t want to admit it? Does religion have a valid place in human society, or would it be best if we all realized it’s a delusion based on fear and ignorance?

It’s a complicated issue, but that’s what good stories are made of—complications, questions, what-ifs. I’m going to keep thinking, and writing, about it.

Sally McBride’s novels Indigo Time (Five Rivers Publishing) and Water, Circle, Moon (Masque Books) are available from the publishers, Amazon and other venues. An earlier novel, Remnants of Fear, is undergoing revision and is currently unavailable. Her short stories and novellas have appeared in such magazines as Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Realms of Fantasy, Northern Frights and many more magazines and anthologies. Her novella “The Fragrance of Orchids” (Asimov’s) won Canada’s Aurora Award and received Hugo and Nebula nominations. She has taught fiction writing and edited speculative fiction. Born and raised in Canada, Sally lives in Idaho with her husband and cat.

Sally McBride’s novels Indigo Time (Five Rivers Publishing) and Water, Circle, Moon (Masque Books) are available from the publishers, Amazon and other venues. An earlier novel, Remnants of Fear, is undergoing revision and is currently unavailable. Her short stories and novellas have appeared in such magazines as Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Realms of Fantasy, Northern Frights and many more magazines and anthologies. Her novella “The Fragrance of Orchids” (Asimov’s) won Canada’s Aurora Award and received Hugo and Nebula nominations. She has taught fiction writing and edited speculative fiction. Born and raised in Canada, Sally lives in Idaho with her husband and cat.

Thanks for visiting the Warpworld Comm! Contact us for infrequent, non-spammy, and highly entertaining Warpworld news.