Joshua Converse's Blog, page 3

December 17, 2017

“Wizards in Winter: A Christmas Tale”

Years ago, when I first encountered the Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s track “Wizards in Winter,” I wanted to write a Christmas story about wizards. This last November, however, I devoted my efforts to writing a werewolf novel entitled The Diana Strain. At the end of that novel, which I finished writing on November 28th, I felt elated to have completed the first draft. This lasted two days, and then the writing hangover hit me and I felt the way people sometimes describe the feeling of missing a day at the gym– I felt my (writing) muscles atrophying, my powers diminishing, the flow that had animated my days was drying up. Something had wanted to get out, and now it was out, and I felt like an empty vessel spent. It then occurred to me that I ought to write that Christmas story, after all, but by then I wasn’t sure how to begin. I had spent too long thinking about it and envisioning it, and building it up in my mind, and now it had grown intimidating and tough to break into.

Fortunately, I have a friend named Elle Otero, who is working on an amazing mermaid novel series right now, and she was kind enough to agree to help me out of my slump by doing something neither of us have done much of before: co-writing a short story. We decided each of us would write freely, one then the other, tagging out when one of us felt we’d written enough. It has been a rewarding experience, and surprising sometimes when things take a turn neither of us expected; the writing process itself has been like a sleigh ride through a strange, enchanted Wood at the side of an absent-minded wizard. The story itself strikes me as something Tolkienesque and Dickensian at once; it recalls the tradition of telling tales about ghosts and goblins, magic and fairies on a dark winter’s night.

We plan to publish on Amazon/Kindle Singles on Christmas Eve 2017, just in time for Jolabokaflod. Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, Good Yule to all, and consider, perhaps, curling up with a tale of magic this Christmas Eve.

March 25, 2017

Pals

So, there came a day long ago when someone wrote a sentence. He wrote it in a different language.

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

Not lovers. Not family. For his friends.

Friendship is really the highest form of human bond. I don’t mean what Facebook means by “friends.” I mean friends more the way Homer meant it, when Achilles, the greatest warrior alive among a litany of superlative warriors, sat out the greatest war of his age to mourn for Patroclus. Some quarters have tried to make out they were lovers. I contend they were friends. And friends means something really important, and strangely cheapened in this contemporary moment.

We are blessed to have real friends in this life. Mostly, we surround ourselves by acquaintances, at best. Real friends will fight for each other.

A few years ago, I had someone I considered a best friend walk out. We had political differences. Ideological differences. For my part, I’m still his friend. Still willing to be there, lay down my life, and the rest of it. It is a wound that’s never fully healed that he walked away. What it’s taught me is this: friendship is unconditional. I’m still his friend. Even if he’s absent. If he called tomorrow and needed something, I’d be there. That’s the nature of friendship.

Look at Sam and Frodo. Or Quincy Morris, John Seward and Arthur Holmwood. Look at the novels of Austen. Friendship matters, and it’s not to be overlooked or cheapened. Real friendship, real loyalty to someone else, is of more worth than all the diamonds on Earth.

Think on what we’re here for, if not each other.

December 13, 2016

The Distracted, the Dishonest, and the Superficial: The Internet as an Engine of Ignorance.

I have become convinced that the Internet, as it exists today, is hostile to deep thinking, meaningful discourse, and, ultimately, democracy. It is worth mentioning here that, according to CNN, somewhere between 96% and 99% of the internet is really the so-called Deep Web, and most users never access it–the remaining 4% of the World Wide Web is mostly porn (15% or so, according to Forbes) and a considerable amount of misinformation. The effects of the Internet on thinking are still under debate, but undeniably, with three billion users worldwide, it is the single most pervasive medium for the myriad forms of human communication (and therefore thought) on the planet.

Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman describes two systems of cognition in his book Thinking Fast and Slow termed, somewhat aptly, System One and System Two. System One is fast, automatic, and stereotypic. It constructs simple stories based on little to no evidence (provided these stories fit with what one already believes), and it is confident in those stories if they are associatively coherent. For example, if the news reports a white police officer has shot a black suspect somewhere in this country, System One will, for many, immediately construct a story about racism because it confirms what they already believe. The facts may or may not support this story System One is telling us, but that story and the emotions accompanying it have real world consequences. System One is, therefore, the source of a number of cognitive biases because it deals associatively, emotionally, and (often) invisibly.

System Two, however, is effortful thinking; it is required in calculation, and it does mental work. It is also lazy, and very finite in its ability to process much of what human beings naturally feel, think, and experience. Kahneman’s example is that a person is like a newspaper, and System One is like reporters delivering stories which System Two, as editor, must sign off on– it either endorses a story or it detects a mistake and sends it back for further processing. By and large, a paper is guided by its reporters in terms of content, as a person is shaped and guided by System One. Therefore we are all are largely guided by the more unconscious, flawed, emotional, associative and biased mental system. Our impulsive, quick-thinking self is prone to mistakes, and we are confident in those mistakes if they are in accord with what we already believe.

One of the wonderful things about books, in my opinion, is how it slows the reader down. A book, particularly a great book, is a deep meditation on a subject. One has time to ponder and reflect, or follow the thread of an argument or idea. The effects of a book are cumulative. In his article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Nicholas Carr comments on the difference between reading a book and “power browsing” on the Internet “Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.” Books invite us to dive in and immerse ourselves fully in an idea. We are often engaged in effortful mental work (Kahneman’s System Two) when we are reading substantive books, and when we read, we descend on a vertical plane from beginning to end, cover to cover. It requires attention and focus to read a book.

The lateral, fragmented, attention-span depleting medium of the Internet is wholly unlike typographic media. The Internet as it exists today is an immediate, distracting, fragmented platform. Almost no Internet site is readable the way books are; inevitably there are ads, hyperlinks, multiple windows, additional tabs, etc. The point is speed and fragmentation, not depth and coherence. The internet value of immediacy is at odds with the typographic value of reflection. The internet value of multi-tasking is at odds with the typographic value of prolonged focus.

By dint of the Internet’s size, around 1.2 million terabytes, search engines must prioritize or “decide” what information to deliver to a user. The solution was to develop algorithms, and those algorithms key to much more than just relevant search terms. In fact, as Eli Pariser says in his 2011 TED Talk, Google, Facebook, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and almost every other major news source is delivering information based on age, sex, location, search history, and what a user has clicked on first in the past. In other words, the Internet is creating echo chambers wherein users see what they want to see, and their own understanding of the world is confirmed. “The impulsive self” as Pariser has it, (that is to say the self that does not deliberate but simply acts; the System One self) is building an echo chamber of its own biases in collusion with advertisers, news media hungry for clicks and “likes” and “shares,” and internet sites that want as many users to remain logged in as possible.

So, the Internet is full of distraction, and largely feeds into System One thinking, impulsiveness, speed, and a lack of deep thought. It is also the ascendant and pervasive medium for global news, communication, information, social interaction, etc.– but the Internet is full of misinformation, disinformation, spin, and propaganda. It is no coincidence that 2016 is being referred to as the beginning of the “Post-Fact” epoch. Newspapers have cut their fact-checking staff from hundreds in the mid-twentieth century to dozens or fewer in many cases. The Internet’s immediacy and speed, coupled with the advent of 24 hour news channels has made the cumbersome work of getting a story right a suicidal impulse for any news outlet. Witnesses to a mass shooting or a disaster can and do “tweet” the details of their situation in real time. To compete, news source have compromised accuracy and objectivity for pandering to a political demographic, and whenever possible, being first.

We are living in the dark future. We are living in a time when digital technology is rewiring our brains. In the Foreword of his prescient book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman writes of the competing dark visions of the future put forward by George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, “Orwell warns that we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression. But in Huxley’s vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity, and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think. What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive of us information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passvity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feels, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy.” Consider in the light of Postman’s observations and Huxley’s fears, the culture that has coined the “selfie” and canonized the Kardashians. A culture that has elected as President of the United States a man like Donald Trump; a reality television star without respect for, or interest in, accuracy, reality, or truth. A culture that put forward a candidate like Hillary Clinton who told her donors it was important to maintain a public and private stance on matters of policy, and whose relationship to the truth could kindly be described as “mentioned when advantageous.” Farhad Manjoo, in his book True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, writes, “On the Web, television, radio, and all manner of new devices, today you can watch, listen to, and read exhaustive and in insular detail, the kind of news that pleases you; and indulge your political, social, or scientific theories, whether sophisticated or naive, extremist or banal, grounded in reality or so far out you’re floating in an asteroid belt, among people who feel exactly the same way.” The Internet’s filter bubbles and echo chambers are the reason so many are surprised (and hostile) when they are challenged by different ideas; they don’t encounter liberalism/conservatism/etc. online if they don’t want to, and if they do they can always “unfriend” and “block” the offending party, or retreat to a “safe space.”

I would like to put forward the suggestion that the Internet, as it exists now, is responsible for much of the superficiality, misguidedness, and incoherence at large in the world today. We are being conditioned to think in 140 characters, we are dumbing down or silencing real discourse, we are declaring our solipsistic ideologies or empty slogans (necessarily without nuance) in memes, and we are being fed clickbait confirmation bias, and inaccurate/ incomplete misinformation or deliberate disinformation at almost every turn.

I am not sure how to address the problems I have raised in this (ironically internet-based) blog post, but I think the first step to solving a problem, cliched as it may sound, is to admit there is a problem. Democracy depends on well-informed citizens– it can’t withstand a pervasive global apparatus that undermines effortful deliberation, tells users what they wish to hear, occludes facts by overwhelming them, and unceasingly sells trivial, vapid, or false information. The hinges are beginning to rattle with the rise of Donald Trump, a man who is the incarnate love child of Manjoo’s Post-Fact Society and Postman’s vision of Show Business as Public Discourse. The genie, as they say, won’t go back in the bottle; we can’t return to a purely typographic world, or even the world of television as it existed through most of the 20th century. We are going to have to negotiate with this ascendant technology in a way that doesn’t leave us mentally and socially enslaved and ensnared by the World Wide Web.[image error]

July 24, 2016

Lackland, the Alamo, and my Brother.

I expected my brother Ryan’s graduation from Air Force Basic Training at Lackland AFB in the Texas summer of 2016 to be like (and unlike) my graduation from Army Basic Training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina in the summer of the year 2000. It was uncannily familiar, but with differences enough to make me feel I was in a parallel universe. Our grandfather was drafted into the Navy during the Korean War, and when the three of us met on the Parade Ground where my brother marched, saluted, and took the oath of enlistment, I (we , I think) felt two centuries of American tradition like a shared, beating heart between us.

My first surprise was how similar it all felt for my Grandfather and me. To be sure, there were differences in uniforms, in nomenclature (Platoons/Flights? Drill Sergeants/ MTIs? Battle Buddy/Wingman?), and so forth, but there was also tremendous similarity in method and doctrine. Even for our grandfather, who had been a Junior NCO in the Navy in 1952, it was startling how much of what had happened during his training happened also during Ryan’s; the running, the gas chamber, the rifle range, the marching. After all, Drill and Ceremony alone stretches back to Valley Forge in the American military tradition. The 1% of the American population that comprises the active military and the 1% that comprises our veterans are part of something that the rest of the country really can’t fully understand. Our common experiences are a common bond of brotherhood. Era is irrelevant.

What surprised me even more than how much things were the same was how much, despite inter-service differences (call them fraternal rivalries, if you like) and the changes wrought by a passage of years, the Air Force was not quite as soft as I thought. I worked with Air Force personnel while I was in the Army, and they’d brought back stories of never having even been to the rifle range during Basic Training, or never having even held a rifle. My brother Ryan not only fired a rifle, but qualified expert with one. I remember feeling our Army PT standards were more exacting than that of our Air Force brethren, but it seems whatever gap there used to be has been at least somewhat shored up. Granted, they run a mile and a half instead of two miles, but my brother ran that mile and a half in 10 minutes and change. That’s probably as good as I ever was over the same distance. Maybe better. The point is, it’s a real achievement to have done what he’s done. He excelled academically, physically, and mentally. He helped square other members of his Flight away. Some of them came up to me and shook my hand and told me how he’d helped them get through Basic Training. My little brother, who I’ve always tried to look out for, was looking out for other Airmen. These are kids who have raised their hands and, in effect, written a blank check up to and including their lives to their country. Ryan helped them make it, and he made it himself. What could make a man prouder?

Later, we ate our way through San Antonio, going from place to place so he could have all the things he’d been dreaming about for eight weeks. We visited the Alamo, and all I could think was how fighting men of every age left their mark–how each generation contributes to history. We walked over ground where a handful of brave men fought and died against a much larger force, and in the process they became legends. In his time, my grandfather was assigned to the U.S.S. Philippine Sea, a Navy aircraft carrier. This ship and others like it were there on the Bikini Atoll participating in tests of the first Hydrogen Bombs. I was part of Operations Iraqi Freedom, Enduring Freedom, and before that Operations Northern and Southern Watch. What part will my brother play in the events that shape the world to come? I’m not sure. I pray he doesn’t ever go into harm’s way, but I know if he does, he’ll be helping the people to his left and right make it through. That much I know for certain.

February 1, 2016

My First Day

Maybe I should have been nervous, but I wasn’t. To be honest, teaching my first class at Monterey Peninsula College felt like coming home. My wife works there as well, and we drove in together. She snapped a couple of pictures of me outside my class, and then she went off to work and I waited for my students to arrive.

I attended MPC as a student for some years and got my AA there. I knew these classrooms and buildings. I had friends in every corner of the campus. When students began to pour into my classroom, they didn’t feel like strangers, although I knew none of them. They felt very familiar: I had sat beside their like and been one of them not so very long ago. There were kids fresh from high school (or even in high school doing Independent Study), older students returning to school looking to begin a new career, and people coming off of night jobs to attend my 8am class. There were nursing students and football players and kids from the tough side of town, and as they filed in I welcomed them all. These were my people.

I had been warned my lecture would go over their heads. Frankly, I think some of it did, but I never saw anyone check his watch or glance at her phone (though I forbade compulsive phone-checking right away)– more importantly I never saw a glazed over eye. Even if they didn’t completely understand every word, they were interested. They were present. I reviewed my syllabus, delivered my brief lecture, assigned an in-class reading, and then we discussed it briefly. This was an English class, just below transfer level, and even on the first day I wanted to get them thinking about what that would mean. At the end of the class, I gave them a writing prompt that had to do with our reading (Julio Cortázar’s “House Taken Over“). They filed out.

The next class is on Wednesday. I can’t wait.

January 8, 2016

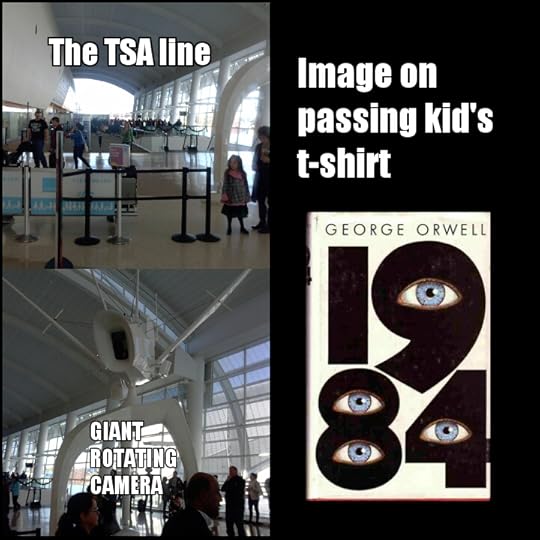

1984 in 2016: The unblinking electronic eye.

Every month, more or less, I go and pick up my daughter at the San Jose Airport, and then I send her back to her mother the same way after a few days or a week. Again we drive to the airport. We stand in the security line where we are informed we must remove our shoes and divest ourselves of any liquids, that if we see something we must say something. We are apprised as we wait of the newest regulations devised by our guardians to keep us safe. I grit my teeth. I put her on the plane.

At the top of the stairs beside security and the exit for all gates at this particular airport is a piece of what I suppose could be called modern art: a very tall white machine with a rotating camera and monitor apparatus spins constantly round and round, giving the once and future passengers and their waiting friends and family a quick flash of themselves in the huge rotating eye of the white giant.

Last month I stood there beside this monstrosity and awaited my daughter’s emergence from the throng of holiday travelers, and a young man (too young to remember the world before 9/11) passed me wearing a 1984 t-shirt. The famous year of Orwell’s bleak dystopia was fairly bulging with accusatory eyeballs, and as the kid shuffled passed he aligned for the briefest instant with the towering camera/monitor, and further on with the brimming security line.

I try to attend to moments like these, because they are perfect in their way. For a moment art, literature, fashion, history and geopolitics converged before my eyes as I stood alone in the crowd and watched it happen. The surveillance is overt at this airport and most airports across the United States; the security measures are deliberate and audacious, and our collective willingness to submit ourselves, electronically denuded and in our stocking feet, to TSA’s gestures toward competence and authority in exchange for a nebulous, demonstrably false promise of safety simply goes without saying after 15 years of living with it. It almost feels redundant to call the moment I experienced “Orwellian.”

And so, I recorded the moment as best I might: snapping a few pictures with my internet-connected camera/phone, though it has until recently been subject to datamining by the NSA– for I have learned to love surveillance.

August 16, 2015

Why I Prefer Superman

There is a divide among comic book folk: Batman or Superman? Most people these days, I would say, prefer Batman. I understand. Batman is great. In the Age of the Anti-Hero, Batman is King. He is an extraordinary human being who always has a plan, who has honed himself to near-perfection–he is the pinnacle of what a human being can fashion himself into in pursuit of an ideal. Batman is also a thoroughly Gothic character; the Dark Knight. Batman is the reason the criminal scum of Gotham fear to go out after dark. That captures the imagination powerfully, and I have always enjoyed reading Batman comics. To top it off, I think Batman has the greatest Rogues Gallery in comics, hands down. Superman’s enemies are comparatively ill-used, frequently mediocre, and somewhat one-note. I humbly acknowledge all this.

Superman, on the other hand, is a bit hokey. Mr. Primary Colors. His invulnerability sucks all the risk out of his adventures. His moral uprightness and incorruptibility makes him an unrelatable anachronism to many. And, to be honest, the writing in his comics has often been lackluster for decades. I can understand why people don’t care for him as much as others in the DC world. And he’s unpopular, I think, because of years of bad writing, bad ideas, puerile notions of what Superman is and isn’t– and because the American people are being taught not to believe in the things I think Superman stands for.

But hear me out: Superman is the iconic American story. An immigrant, an orphan, who finds a home in America’s Heartland. Why not San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, or New York City? Because a farm in Kansas is a place where, even when Superman was created, old fashioned values remained. Superman was raised to believe in an ideal–indeed, he became the iconic embodiment of the American Ethos. He’s often referred to by detractors as “the Boy Scout,” but I would argue this is precisely what you want in a being with as much power as Superman has. Anything less than respect for the Constitution, for Justice, for Truth, would be terrifying. Consider Superman, (as he was considered in Red Son) in a more totalitarian state of mind: terrifying. Without respect for human life, without the “Boy Scout” mentality, Superman becomes something objectionable and frightening. An alien presence come to enforce its will. But that’s not Superman. Superman is what he is because of American Midwestern values: he is an exemplar. No mask because he doesn’t want people to think he’s hiding. Bright uniform, because he is a shining example. Superman is what most of us aspire to be (or should): strong, brave, powerful, just, and good. Who wouldn’t want to be Superman? On the other hand, who would want to be Batman? Batman lives a tortured existence. He is lashed constantly by painful memories that drive him on to obsessive heights. He suffers, and his life is a long night of doing violence and planning to do more–to be sure it’s for the greater good, but he doesn’t want to be the example. He wants to cause fear and be a deterrent. He wants to take down his enemies, breaking but not killing. Superman, on the other hand, is an example anyone (powers or no powers) can aspire to in acts that are helpful, brave, and noble. Anyone can follow Superman’s example. Few can successfully follow Batman’s, and few would care to. After all, Batman’s life is pain. Superman’s is difficult, but not tortured. Superman has relationships that keep him in touch with humanity. Batman must often withdraw–his is estranged to almost everyone he cares for, in the end.

In Plato’s Republic he raises a question about the Ring of Gyges–a magical artifact that grants total invisibility to whomever wears it. Is it possible that a man in possession of this ring could fail to be corrupted by it? Would he not use it to slake his lusts and settle scores? In many respects, Batman and Superman are both paragons of honor, but Batman uses the shadows, uses the darkness, uses his “invisibility” to instill fear in the worst of humanity. Superman uses the light to try to elevate the best in us. He is not corrupted by his power, but rather uses it to try to show others their own power, and how not to be corrupted by it. There’s no getting around it: Superman is an American Christ-figure. These days, that isn’t so popular. Church-attendance is at a historic low in this country. Mentioning Jesus in an unironic way is a bit of a conversation-ender in circles urbane and plebian alike. Consequently, there is an antipathy for figures that are “too good” in comics. How can someone “too good” be interesting? To my mind, writers have shied away from really asking him the hard questions: To what extent is he willing to let humanity misbehave? How far is too far before he intervenes in more than just helicopter crashes and starts to enforce international treaties? How much right does he have to punish sovereign nations for funding or carrying out terrorism? What does he do with all the information he gleans from “listening in” on what should be private conversations, and how does he deal with seeing the ugly truth that sometimes goes on behind closed doors? It’s not a question of strength and muscle, or bullets bouncing off his chest. Superman is interesting because of what he won’t do. How do you do the right thing and still allow for free will, individual choice, and basic human rights? These are important questions that, if I were writing for The Man of Steel, I would address.

As for patriotism, in the halls of the academy and in half of the political divide, it’s fashionable to dismiss much that might have been considered good or noble in the American character, history, etc. Today, “heroes” are best if troubled, queered, re-gendered, racially altered, or otherwise “updated” to be more in keeping with “the new normal.” I like Superman because he’s old school–and no matter what the writers do to him (and believe me, I’d like a crack and writing his comics) I will always understand what Superman is about: Truth, Justice, and the American Way. I believe in those things.

Batman isn’t hard to imaginatively transplant to Victorian London or Medieval Europe, (as Elseworlds lines have done) but I think Superman’s Elseworlds lines miss something essential in the character if he is not an American: he’s not dark, he’s not cynical, he’s a ray of hope in a world of possibility. That was us. That was what the American Revolution was supposed to be about. We were meant to inspire the world to throw off the yoke of tyranny and peaceably self-govern. That’s why Lady Liberty holds a torch. It’s a beacon. It’s hope. I want to believe in hope. I want to hold it up and say “This is what I believe in.”

I’m glad Batman’s out there in the night, keeping Gothamites safe. Being the watchful protector. And I love the Justice League entirely, but I will always prefer Superman because I believe in the America that Superman exemplifies. I think we can be that hope in this world.

August 5, 2015

#IbelieveinKenHickey

In the Army, we had good leaders and bad ones. I want to talk about one of the great ones. SFC (later MSG) Ken Hickey of the U.S. Army did not let his soldiers down. Let me say that again: SFC Ken Hickey of the U.S. Army did not let his soldiers down. Ever.

Consider the magnitude of that during a war and in an environment that is doing its utmost to ruin your plans. Nevermind the 114 degree heat. Forget about the incessant fatigue, the constant danger, the oppressive workload, the SCUDs flying over, the choppers crashing near where we slept, the hand grenades and suicide bombers in camp and the danger of going out beyond the berm–the man simply would not stop. He had to make sure we had whatever we needed. He drove hours a day risking IED and ambush to make sure his people were safe, fed, and had got their mail. When things happened, Ken Hickey ran toward danger. His spirit was unbreakable, even when things weren’t as they should have been at home.

Today, he’s retired. Divorced. No children but the soldiers he once led. He lives alone, an hour from the nearest family member. After 24 years of service to his country, he settled in a simple home on a quiet street. He buys bicycles and donates them to Toys for Tots at Christmas. He hands out gum to the neighborhood kids. He mows his Army neighbor’s lawn while he’s deployed, so his neighbor’s wife doesn’t have to. He brings positivity to his Facebook feed with his “Hero of the Day” posts where he recognizes the outstanding work of others. Ken Hickey is one of the kindest men you could meet. It’s not a cliche to say he would give you the shirt off his back, because he damn well would.

He’s also in the grip of PTSD and an alcohol addiction so severe he spent a month in a coma last year because of it and died on the table at one point. His injuries from that episode have made it harder for him to get around, and much of his physical strength has left him. Since then he has been in and out of the hospital, sometimes for a week, sometimes a few days. He drinks, doesn’t eat, his body shuts down, and he goes into the ER. This is the pattern. This is the cycle. It’s a terrible cycle with lethal possibilities.

When I think of this, I picture him alone in his house with the most malevolent, sentient, awake, evil force imaginable actively trying to kill him, drink after drink. Life goes on outside, cars pass, people have their family dinners and barbecues down the street, soldiers come and go on the post nearby, and Ken sits alone in the dark in the grip of this monstrous addiction that wants nothing less than his life.

But it can’t have him.

His soldiers are in a fight for Ken’s life today. Incredibly, after a week and a half of phone calls and false starts, (three of his old soldiers pushing him and planning the whole time) Ken checked himself into a 2 week detox program. It isn’t a slam dunk, but it’s a good start. His friends and family are rallying to support him in his fight.

Unfortunately, so many of us are far away. I’m in California. Ken’s in Louisiana. Others are as far away as Georgia or Washington D.C. or even overseas. What we can do is limited. We’ve sent him pizza when he wasn’t eating. We’ve sent letters and care packages. We’ve called and talked for hours. We’ve looked into longer-term treatment programs and tried to provide a sympathetic ear to his family. Is it enough? I don’t know. Ken needs longer term treatment and care to make it back, and he has to want it. He has to believe.

So, as a way of showing support, we’ve begun a hashtag campaign to show Ken just how many of us are behind him. It won’t solve all his problems. It won’t fix what’s broken, I know. But maybe in the dark moments it will get him through to know how many people love and support him, and how important it is that he keep fighting–that he stops drinking and gets help.

Join us in supporting Ken Hickey.

#IbeliveinKenHickey

April 12, 2015

What is Poetry?

When I was a smug, difficult undergraduate (not the slightly-less-smug, equally difficult grad student I am today), the put-upon but patient grad student teaching my section posed this question to the class:

“What is Poetry?”

I was too quick to answer: “Poetry in the Western Tradition was simply meter and verse for centuries; a stylized, metered form of expression. Then came Modernists like Gertrude Stein and, later, free-verse ascended, and the��zaum poets carved out their post-rational niche and Postmodernism goose-stepped onto the scene… and now the waters are so muddy you have to ask, with gravitas and sincerity, ‘what even qualifies as a poem?'” I want to apologize to that poor grad student now for being so smug and so certain. I have considered this question for years since, and I think maybe I have a more considered answer. Perhaps she will rewrite my grade?

So, then what is poetry? How do you define it? Do limericks count? Nursery rhymes? ( After all, Frank McCourt, author of Angela’s Ashes�� and Teacher Man��wrote once his favorite poem was “Little Bo Peep.”) Is poetry present in a recipe for stew? Is the back of a cereal box poetry? Is poetry simply rhyme and meter? For some holdouts, formal poetry is the only poetry worthy of the name. Others say you don’t even need real words–you can make it all up and it can mean whatever you want it to mean. The Beat Poets prized spontaneity and the spoken word over carefully prepared stanzas sitting ordered on the page (and some Beats prized spontaneity so highly, they never left it to chance). ��If we say “everything is poetry” then nothing is.

Can we define poetry categorically as a form of human expression, written or spoken; a distilled form of language designed to reveal something about the inner world of a human being, or that human being’s relationship to the outer world?

If we accept this as a definition (and I think this is my working definition), then we have already created some boundaries:

1) Human expression. Poetry requires a human to write it. Computers can not write poetry. Gorillas can not write poetry. Humans only. Cyborgs need not apply. No Zombies accepted. (“But wait, what’s a human?” I hear you cry. Fair question– and one worth pondering. Let me refer you to a great place to investigate: David Clemens’ online “Robot” class: “More, or Less, than Human?”)

2) Language: a system of communication that amounts to a list of all possible messages shared by at least two separate entities. The language must be more or less agreed upon. In the simplest terms that means if I write “cup” you mustn’t think “chair.” Forests have been clear-cut to provide for the books that discuss linguistic slippage and language’s inherent instability, but, perhaps ironically, the people who claim to have read them (and claimed to understand at least��some of them) relied on their command of language to grok (Heinlein’s wonderful made-up word meaning deep and complete understanding) just how unstable language really is. Let us suppose that language is imperfect, but manages to work well enough that we can often understand what one another is getting at in expressing something true and accurate, despite myriad problems like noise and misunderstanding, different definitions, etc. to say nothing of tone, context, projection, deception (even self-deception), or misinformation. Engineers manage to use language to build structures that, by and large, stay up. Heart surgeons use language to successfully perform surgery (there’s a name for every line and fold of the body, after all) and homicide detectives manage to figure out whodunit based, often, on the language of confession, or the language of forensic science. By and large, language works. Unless you’re married…

3) Distillation: As with most forms of Literature, nothing superfluous should exist within a poem. Everything that is there is there on purpose. Ph.D. Candidates spill small oceans of ink in their dissertations over the use of a particular comma in a John Donne poem.��Everything on the page is up for analysis, and is there contributing to the experience of the reader. This means that poems, especially shorter poems, are often some of the most meaningful and tightly-packed words in a language. Billy Collins, former poet Laureate of the United States and sometimes reviled champion of approachable poetry (I quite like him, but that’s neither here nor there) once wrote in his poem “Baby Listening:”

Lucky for some of us,

poetry is a place where both are true at once,

where meaning only one thing at a time spells malfunction.

Poems aren’t always ambiguous, and aren’t obliged always to multiple meanings at once, but it is generally true that poems resist “final” meanings. That is to say, to borrow from David Steiner, “Great works are inexhaustible.” Poetry (good, great, or not so great) should be distilled to mean as meaningfully as it can in the few words by which any poem exists.

4) Revelation: Poetry tells us something. Ideally, I think, it names something or provides a reference for something unnamed inside us. Consider how impoverished English is (one of the most expansive, enormous languages in the world) when it attempts to describe love. Love has been a poetic subject almost from the beginning, and yet today, probably at this moment, thousands of poets are putting pen to paper trying to describe what it is like to be in love with another human being.

We have terms like “puppy love” and “passion” and “romance,” and they serve in their way– but consider the vastness and variety of what love really means. Love for a parent, a child, a lover, a dog. We use the same words, “I love you,” but inflected are nuances and distinctions that go largely unexamined and unspoken. Is “love of country” different than “God’s love” which is itself different than “a mother’s love?” They share commonalities, but those poor Ph.D. candidates I mentioned before could abandon Donne’s comma and draft entire libraries on the distinctions between these different “love” ��sentiments.

Consider these three poems and their use of “love:” (After reading them, I cannot but think that “love” is a word as varied as the word “you.” To whom does “you” refer, if not each unique individual? And yet we generally know what is meant when the man in the street points his finger and says, “Hey, you!”)

How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)

By Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day���s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood���s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

The Good-Morrow

By John Donne

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers��� den?

���Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ���twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love, all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest;

Where can we find two better hemispheres,

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou and I

Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.

Those Winter Sundays

By Robert Hayden

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I���d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he���d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love���s austere and lonely offices?

An analysis of these three poems, side-by-side or individually, would fill a (perhaps dry) manuscript, but I use these particularly because I like them, and because I think they are beautifully expressing what we call “love.” Each in its own way. But also, they are collectively expressing, when we put them next to each other, the breadth and range of what (and how) that word “love” can mean.�� Poets enrich our impoverished emotional vocabulary– describing both what is within us, and how we regard what we behold.

Poetry (and Literature, generally) seeks to provide us with inner illumination; a mindfulness of what we are. Poetry is a blueprint that reveals a majestic Capitol City hidden beneath the tiny village where we begin, as Hobbes had it, “nasty, brutish, and short” lives.

If something you read doesn’t seek to do that, it isn’t a poem.

(I think)

January 16, 2015

Heaven: The Big Library

If there’s a Heaven (and I believe there is), I hope it’s a library. The Library, in fact. The place where you can read everything that was ever written, everything that will ever be written, and all that was never written on Earth but was in Heaven. ��There would be no misprints, no bad editions, no faulty translations, and you’d be able to read it in the original–learning a new language is no problem in Heaven as they have an excellent World Language Lab. Angelic tutors are available upon request. There are great rooms where you can go and talk with Plato and Aristotle about the philosophy book you just read.

In this library there would be daily talks by some of the great authors…and in The Presence, even those authors who were most intolerable and pretentious in life will have learned humility. In fact, they will talk about the new books they are working on–the Divine Printing Press puts them out periodically.

They’d always have enough copies of a book that there would never be a need to wait for one to become available, and due dates would be measured in centuries instead of weeks or months. In The Library there would be no computers, just stacks and stacks of glorious books in rooms of golden light. The chairs would be comfortable enough to sleep in, and there would be so many lovely nooks and corners where one could tuck in and read all day.

The Library never closes. You could read for all eternity in peace, and when loved ones arrive to join you…you can sit together on the big lawn outside The Library and admire the counter-Newtonian architecture, and hold hands, and talk about all the books you’ve been reading…