Joe Blow's Blog, page 4

May 13, 2019

BOOK REVIEW : Selected Poetry by William Blake

This is a great entry point to begin exploring the poetry of one of English literature’s great visionaries. Blake’s poetry can make for challenging reading, especially his epic poems which are full of allusions to the Bible, to history, to famous philosophical works and also to individuals who were important in his own life. And, to make it even more difficult, many of the mythological figures who appear in these poems were Blake’s own creations, the nature of whom we have to try to pick up from the context. (The footnotes help to make sense of the allusions and also explain some of the archaic words Blake uses.)

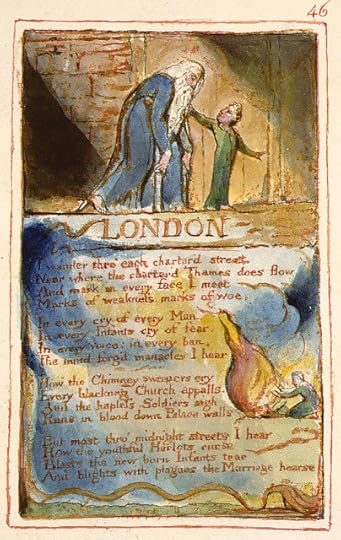

For a long time I thought of Blake as someone who had a big impact on my view of the world, even though I had only read a handful of his poems. While London, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and The Everlasting Gospel spoke to me like the voice of a friend to one lost in a wilderness, the prospect of reading his epic works was daunting. The beauty of this collection is that it contains much of his shorter work, including the entirety of Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, along with extracts which can be read alone from two of his epic poems - Milton and Jerusalem. This helped to give me confidence that I will be able to read them in their entirety at some time. I was also inspired to buy The Blake Dictionary, The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake by S. Foster Damon and Morris Eaves to help with this.

An argument could be made that the way to read Blake’s poems is as he presented them, illustrated with his drawings and paintings. Still, I think there are advantages to reading the text on its own. His words conjure up images which are more powerful than his pictures, amazing as they are. I would recommend reading the poems on their own and then seeking out the illuminated versions afterwards.

What I relate to particularly strongly in Blake’s writing is his vision of the entrapment of the human soul within the repressive structures of society. “A robin redbreast in a cage sets all Heaven in a rage” was not just some superficial animal rights statement, it was a cry for freedom from repression of the human spirit.

Good and evil, in Blake’s eyes, were not so simple to distinguish. He used the term “moral virtue” to label a form of self-righteous judgement which viewed itself as good, but was the enemy of love and love’s forgiveness. By contrast the vital energy we feel in our bodies might be viewed as a source of sin by the church, but, by Blake, as a source of “eternal delight” for “everything that lives is holy.”

Blake’s was very much a pantheistic vision. The divine was always present in nature, and, while he had visions of angels and demons, he didn’t believe, in a literal sense, in miracles which defied the laws of nature. He didn’t believe that Mary was a virgin (Jerusalem, Chapter III, lines 369-393), and from this he draws his own vision of Jesus as a child of love and of liberation from the law’s oppression of love. Mary was impregnated in an act of love unsanctioned by the law. Joseph, discovering that his betrothed was carrying another man’s child, had to exercise forgiveness in keeping with God’s forgiveness of human sinfulness, and love for life rather than for the law, to marry Mary. Thus, in his very conception and the family circumstances into which he was born, Blake sees Jesus as an embodiment of love supplanting law.

I don’t believe in the supernatural, so that kind of religious belief which depends on belief in literal resurrection of the dead, etc., is not accessible to me. William Blake is someone who helps me to draw inspiration and hope from religious visions in a metaphorical sense. If we can cleanse our “doors of perception” perhaps we can achieve a “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and “build Jerusalem” in our own “green and pleasant land.”

Published on May 13, 2019 06:40

March 20, 2019

The Psychological Roots of Patriarchy

Photo by Andrey Kiselev

Photo by Andrey KiselevIn listening to a talk by Jordan Peterson I found myself once again thinking over the disagreement he has with feminists over whether our society is a patriarchy. It seems to me that this a disagreement which can only be resolved through an acknowledgement of what I have called the human neurosis and the phenomena of the character armour to which it gives rise.

Patriarchy is defined as “a society or government in which men hold the power and women are largely excluded from it.” This has clearly been the case throughout much of our history, but in all areas of our society and government women now play a large role, so one could reasonably argue that our society is either no longer patriarchal or that the patriarchy is on its death bed.

I have also seen patriarchy defined as a “male-role orientated” society. Jeremy Griffith of the World Transformation Movement uses that definition, though I haven’t seen it used elsewhere. If we were to take this definition then I would say that we do live in a patriarchal society and that feminism is doing nothing to change this. Historically the female roles have been nurturing roles arising from the biological fact that women give birth to children. Business, politics, science, medicine, the military, the clergy - all of these have been fields historically dominated by men. Those who fill roles in these disciplines continue to be the individuals who have the most power and respect given to them by society, even if “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.” Feminism has allowed more women to enter these fields, but it has not changed the dominant nature of these roles. Now I’m not trying to say what should be. Clearly science, medicine, business, etc., are crucial and I’m not suggesting we somehow try to reduce that importance in order to achieve some kind of balance with the nurturing role. I’m just trying to acknowledge that things are not so clear if one uses this alternative definition.

Some aspects of patriarchal organisation arise for practical reasons. Think back to the time of our hunter/gatherer ancestors. In a time of peace between tribes, the nurturers would call the shots, but, in time of conflict, authority would have to be transferred to the defenders of the group. Wherever a task which was performed by males became temporarily more important to the group than the nurturing role, power would shift to the males.

But then we have the neurotic element. When our developing intellects arrived at the concept of idealism, i.e. that it is meaningful to distinguish between forms of behaviour which promote the integrity of the group and forms of behaviour which work against the integrity of the group and to strive to promote the former and discourage the latter through self-discipline and group imposed discipline, our self-acceptance began to be undermined. Unable to fully meet our new-found ideals, we began to feel guilty. This is what is symbolised in the Bible in the story of Adam and Eve eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and being cursed by God, excluded from Paradise (a state of blissful unity with each other and the natural world) because of “sin”, i.e. non-ideal behaviour. Ironically it was not our behaviour which continued to curse us, but our habit of self-condemnation in the face of that behaviour.

We became deeply insecure about our own worth and this is what made us ego-embattled. Our propensity for selfishness, aggression, delusional thinking, etc., all arose from this pervasive sense of insecurity.

Because women tended to stay closer to the nurturing role and thus could more easily view themselves as “the good guys” engaging in behaviour which promoted the integrity of the group, it was the males who tended to become more insecure about their own worth. The role as group protector was essential, but their newly acquired conscience could tell them that killing people was wrong. They tended to fulfil roles which were more likely to lead to a guilty conscience and thus a greater insecurity about their self worth.

One of the symptoms of this insecurity was the need to control others and to suppress the critical voice. The outer had to match the inner. In the severely armoured man, the critical voice of the conscience is deeply repressed, and this is achieved through inflexible controlled habits of thought. The freedom of others is felt as a threat, partly because it calls out to that which is repressed in the armoured individual, making the maintenance of discipline more difficult, and partly because they may use their freedom to criticise the armoured individual. They are a potential ally to the individual’s own repressed critical conscience.

The patriarchal structure of society historically has been shaped by this psychological condition. There have no doubt been other practical factors, for example it makes sense that, when military conflict arose, men would generally be the fighters, because women, as the producers of children, are too precious to sacrifice, and also men tend to be bigger and stronger. But we can’t understand the way that female voices were excluded unless we acknowledge the fragility of the male ego as a result of the negative feedback loop between egoistical behaviour and the very insecurity driving that behaviour.

Understanding the human neurosis brings a sympathetic understanding to our assessment of our history and to our response to current circumstances.

Our history, horrendous as it has often been, could not have been other than it was. We made the best of a bad lot. It was in the best interests of all that society hang together in a way which allowed us to make progress in our understanding of ourselves.

So where are we now. We still suffer from our neurosis. The fact that women can fill more positions which were once filled by men also means that, if filling those roles makes the individual more prone to the human neurosis, our society probably has an even less healthy base.

The other side of this neurosis is that those who have been controlled, excluded or abused by the most armoured of individuals, are liable, understandably, to build up feelings of retaliatory hostility. And, sometimes, the power of these feelings can obscure the distinctions between the individual responsible and the group to which they belong. So it is not surprising that some will cling to the perception that our society is an oppressive patriarchy, seeing in the complex pattern only that which reflects the shape of their own trauma.

The solution is to open up understanding of this psychological substructure of our society and promote paths to healing for all. Political change on its own can’t assure us a healthy free and productive society. To the degree that we manifest psychological security as individuals, so will our society be characterised by freedom, respect and appreciation for all its members.

Published on March 20, 2019 23:48

Joe Blow's Blog

- Joe Blow's profile

- 7 followers

Joe Blow isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.