Iris Lavell's Blog, page 13

July 1, 2013

Another Tale from the Dark Mountain by Pat Johnson

Book Length Project Group member, Pat Johnson has written a series of fairy stories or allegories collected under the title: "Tales from the Dark Mountain". The Coffee Bean Babies was an earlier story posted on this blog. There is an open-endedness to these stories that encourages the reader's active imaginative engagement. Hope you enjoy this new one from Pat.

The Mountain Spring

The Mountain Spring

Far away on the other side of the world a village rests on the face of a dark mountain. Early every morning when the villagers awake from their night time dreams they hurry out into the sunlight. Dressed for a day of work, they walk together down the mountain.

Today they have a lot of work to do because their whole village is lying on its’ side and all of the villagers want to rebuild their homes and their barns. They begin to hammer and saw, when from deep beneath their feet they hear a great rumble from inside the mountain. They stop their work to listen and they hear it again and again; three times it resonates like sound made by a big bass drum. Then there is a great hiss like a snake and a geyser of water suddenly shoots into the air.

At first the villagers think that this is widecrazity. Why was a geyser in the middle of their village? Then they wonder if they are working in a spot which the mountain wants for something else. After all the village is not where it used to be. The explosion of the mountain moved it to a different location. They decide that they must move, so they begin to think about where they should go. Where is another good spot to build, to live?

Suddenly they notice that the geyser is forming a pool of water around itself. The villagers hurry to collect their children, their beds, pots and tools before they are submerged! Then they taste the water and find that it is delicious, cold and refreshing. So they decide not to move too far away from the delicious water; they go just a little way up the mountain and begin to build there.

The villagers spend their time drinking the water and working on their homes. All the men and all the women have come to love the fresh spring water. They drink it every day and everyday they grow a little bigger. Soon they are so fat and so round that they look like a bunch of balloons bouncing around on two string legs.

They children do not find the water delicious. They have not been drinking so much of the water as the grown-ups and they have not become large like them. They do not like the way the adults have changed and become fat and bouncy. They are beginning to be afraid of their parents, afraid of all the adults, and afraid of the water. They decide they will only drink the water from the stream - the stream where they always got their water before and where they have always done their washing.

As the days go by, the adults stop working. Instead they lie down and roll about at the edges of the spring. They love to watch as the water changes colour through the day – pale gold in the early morning, red like blood when the sun blazes at noon, cool blues and greens in the late afternoon, and black as coal at dusk. They are enamoured of the water. They drink it and bathe in it and carry it carefully to their half-built homes. They cannot bear to leave the pool for more than a few minutes. They are besotted. All they want to do is loll in the wonderful water.

This makes the children very unhappy; their parents are not interested in them anymore. All they care about is their new and wonderful water. The children are wary. They keep a careful watch on the adults and a careful eye on the spring but they do not know what they are looking for.

The children continue to get their own water from the stream, avoiding any red flowers, and bringing the chickens, the pigs and cows and horses to the stream to drink. The children do not trust the new spring. They do not trust its deliciousness or its changing colours. They are worried but they are powerless to do anything against the big adults who do not listen.

One day they are watching as the villagers as usual are lounging around the spring, admiring it, trailing their hands in it and drinking it in little sips so that it will last all day. Their string legs have filled out and are as fat as the rest of them.

Some of them are dancing in the water when the children notice that they can see straight through them. They have drunk so much that now they are just made of water. Their skin, like balloon skin, is transparent and they can see the water sloshing around inside. This scares the children but it only makes the adults laugh and laugh. They shake and giggle and roar with laughter. Soon they are all in the pool of water dancing and looking though their skins, fascinated by the water sloshing around in their bodies.

The children watch, very upset, but they don’t know what to do. Then they hear a loud ‘POP!’; one of the biggest roundest adults has split his skin and his water has run right out of him into the pool. This only makes the other grown-ups laugh harder and louder. ‘POP!POP!POP!’ They are all bursting and disintegrating, all their water is filling the pool. It is overflowing and spilling down the mountainside.

The children are horrified. The adults have gone to water. The little children are crying and holding tight to their older brothers and sisters. They watch as the water flows all the way down the mountain to the floor of the valley below. They race down the mountain to look for their parents, to see what will happen.

Down in the valley, the water is bubbling and rushing. The children can see watery arms and legs rising to the surface and rolling under again. Some faces pop up like corks that have been held under. The adults are reforming. Their parts are coming together and firming up. One by one, they stand up and walk toward the waiting children. They pick up their children and hug them. They shake their heads wonderingly and the last drops of water flick off their hair. The children hold their parents tight, feeling their solid bodies.

Together, they walk back up the mountain and when they reach the place where the spring should be, it is no longer there. It is as if it never was. The water has all gone. There is grass interspersed with fine yellow daisies where the spring used to be, but they are too dazed to notice.

The villagers act mechanically; they take the chickens and the cows and the pigs and horses and put them in the barns. The adults don’t really understand what happened to them. So they talk together and decide it is time to go deep into the mountain because there they will be safe. Once they have made this plan they feel much better, and they gather up their children, ready to go.

They travel far into the heart of the mountain. When they have gone far enough they lay down and cover themselves in furs and go to sleep deep in the earth where it is dark and quiet. They sleep for years as the seasons come and go. They are part of the mountain that does not change. And as they sleep they grow strong from the ancient truth of the mountain.

The Mountain Spring

The Mountain SpringFar away on the other side of the world a village rests on the face of a dark mountain. Early every morning when the villagers awake from their night time dreams they hurry out into the sunlight. Dressed for a day of work, they walk together down the mountain.

Today they have a lot of work to do because their whole village is lying on its’ side and all of the villagers want to rebuild their homes and their barns. They begin to hammer and saw, when from deep beneath their feet they hear a great rumble from inside the mountain. They stop their work to listen and they hear it again and again; three times it resonates like sound made by a big bass drum. Then there is a great hiss like a snake and a geyser of water suddenly shoots into the air.

At first the villagers think that this is widecrazity. Why was a geyser in the middle of their village? Then they wonder if they are working in a spot which the mountain wants for something else. After all the village is not where it used to be. The explosion of the mountain moved it to a different location. They decide that they must move, so they begin to think about where they should go. Where is another good spot to build, to live?

Suddenly they notice that the geyser is forming a pool of water around itself. The villagers hurry to collect their children, their beds, pots and tools before they are submerged! Then they taste the water and find that it is delicious, cold and refreshing. So they decide not to move too far away from the delicious water; they go just a little way up the mountain and begin to build there.

The villagers spend their time drinking the water and working on their homes. All the men and all the women have come to love the fresh spring water. They drink it every day and everyday they grow a little bigger. Soon they are so fat and so round that they look like a bunch of balloons bouncing around on two string legs.

They children do not find the water delicious. They have not been drinking so much of the water as the grown-ups and they have not become large like them. They do not like the way the adults have changed and become fat and bouncy. They are beginning to be afraid of their parents, afraid of all the adults, and afraid of the water. They decide they will only drink the water from the stream - the stream where they always got their water before and where they have always done their washing.

As the days go by, the adults stop working. Instead they lie down and roll about at the edges of the spring. They love to watch as the water changes colour through the day – pale gold in the early morning, red like blood when the sun blazes at noon, cool blues and greens in the late afternoon, and black as coal at dusk. They are enamoured of the water. They drink it and bathe in it and carry it carefully to their half-built homes. They cannot bear to leave the pool for more than a few minutes. They are besotted. All they want to do is loll in the wonderful water.

This makes the children very unhappy; their parents are not interested in them anymore. All they care about is their new and wonderful water. The children are wary. They keep a careful watch on the adults and a careful eye on the spring but they do not know what they are looking for.

The children continue to get their own water from the stream, avoiding any red flowers, and bringing the chickens, the pigs and cows and horses to the stream to drink. The children do not trust the new spring. They do not trust its deliciousness or its changing colours. They are worried but they are powerless to do anything against the big adults who do not listen.

One day they are watching as the villagers as usual are lounging around the spring, admiring it, trailing their hands in it and drinking it in little sips so that it will last all day. Their string legs have filled out and are as fat as the rest of them.

Some of them are dancing in the water when the children notice that they can see straight through them. They have drunk so much that now they are just made of water. Their skin, like balloon skin, is transparent and they can see the water sloshing around inside. This scares the children but it only makes the adults laugh and laugh. They shake and giggle and roar with laughter. Soon they are all in the pool of water dancing and looking though their skins, fascinated by the water sloshing around in their bodies.

The children watch, very upset, but they don’t know what to do. Then they hear a loud ‘POP!’; one of the biggest roundest adults has split his skin and his water has run right out of him into the pool. This only makes the other grown-ups laugh harder and louder. ‘POP!POP!POP!’ They are all bursting and disintegrating, all their water is filling the pool. It is overflowing and spilling down the mountainside.

The children are horrified. The adults have gone to water. The little children are crying and holding tight to their older brothers and sisters. They watch as the water flows all the way down the mountain to the floor of the valley below. They race down the mountain to look for their parents, to see what will happen.

Down in the valley, the water is bubbling and rushing. The children can see watery arms and legs rising to the surface and rolling under again. Some faces pop up like corks that have been held under. The adults are reforming. Their parts are coming together and firming up. One by one, they stand up and walk toward the waiting children. They pick up their children and hug them. They shake their heads wonderingly and the last drops of water flick off their hair. The children hold their parents tight, feeling their solid bodies.

Together, they walk back up the mountain and when they reach the place where the spring should be, it is no longer there. It is as if it never was. The water has all gone. There is grass interspersed with fine yellow daisies where the spring used to be, but they are too dazed to notice.

The villagers act mechanically; they take the chickens and the cows and the pigs and horses and put them in the barns. The adults don’t really understand what happened to them. So they talk together and decide it is time to go deep into the mountain because there they will be safe. Once they have made this plan they feel much better, and they gather up their children, ready to go.

They travel far into the heart of the mountain. When they have gone far enough they lay down and cover themselves in furs and go to sleep deep in the earth where it is dark and quiet. They sleep for years as the seasons come and go. They are part of the mountain that does not change. And as they sleep they grow strong from the ancient truth of the mountain.

Published on July 01, 2013 20:32

June 26, 2013

The writing mentor and other thoughts

Lately, I've been thinking about what it takes to be a writing mentor. I had a good one for my first novel, but I struggle to work out why that person was right for me at the tenuous time of attempting my first bona-fide novel. If he had handled the job less sensitively, would I have given up? Well possibly that book, but probably not from attempting another which incorporated some of the ideas - I have a bit of a stubborn streak that usually doesn't let me give up. On the other hand, how do you know if you can do something, until you've done it? Sometimes confidence gives out before the job is done.

Lately, I've been thinking about what it takes to be a writing mentor. I had a good one for my first novel, but I struggle to work out why that person was right for me at the tenuous time of attempting my first bona-fide novel. If he had handled the job less sensitively, would I have given up? Well possibly that book, but probably not from attempting another which incorporated some of the ideas - I have a bit of a stubborn streak that usually doesn't let me give up. On the other hand, how do you know if you can do something, until you've done it? Sometimes confidence gives out before the job is done.My mentor and I have become friends in the long process of writing the book, meeting for the occasional cup of coffee, and not long ago we met for a delicious meal with his partner who also read my book in the manuscript stage and, to my great delight, gave it the thumbs-up. Two mentors for the price of one!

Maybe part of the solution to getting the mentor mix right is in being able to talk freely with him or her about one's random and sometimes fairly incoherent ideas that may or may not make it into the story. I did, and after doing that I would go away and make them a little more coherent in my imagination (some might say, fester in my imagination). My mentor is skilful in resisting what must sometimes be a strong urge to give me 'solutions' before I have had the chance to think them through myself. So maybe a good mentor is, in part, a sounding board with minimal distortion in reflecting back what I want to do, and not necessarily what he might do himself.

A good mentor seems to be one who will help the writer be the best he or she can be, rather than a faultless version of the mentor's idea of what a good writer should be. The mentor needs to be good at pointing out the mentee's existing strengths and skills, and encouraging him or her to build on those. The mentor needs to be able to make suggestions that enable the writer maintain the integrity or feel of the work - and to develop their unique voice. I believe there is little point in simply reproducing what others do when it comes to writing. Cynically following a formula might or might not get you published, but really, what does it add that is of value to what is already out there. A writer's 'voice' is the golden thing that is the result of the unique life they have lived and the way they have learnt (and continue to learn) to communicate this.

With voice comes authenticity. I have mentioned authenticity in previous posts. What I mean by authenticity is not kidding yourself, or trying to get away with something that you know isn't quite right or congruent with the character. The temptation is there when the authentic clashes with the socially popular, or with some sort of truism or social more. I guess if you're a writer sometimes you have to be prepared to put alternative positions, even when they risk making you look bad. If that's what the particular text calls for. So it's not that easy to be authentic, to strip away the social self and really look at what lies beneath, through the characters that we create. It makes us vulnerable (and yet in vulnerability, there is strength). I feel that every book, regardless of how fanciful, contains an element of autobiography, if only because it emanates from the writer's particular take on something. There are embedded assumptions in any perspective, reportage or opinion, this post included. Assumptions can, and should, be changed when more constructive assumptions are able to take their place. I'm not sure that it's possible to have no assumptions, but I'm always open to persuasion.

I think we are nearly all seduced (in one way or another) into small 'p' politics when it comes to self-representation - which I assume all writing is, to some extent. I understand the voice to be an extension of identity beyond the body, which is why silencing people diminishes them. This idea is really well discussed in a classic book written in the nineteen eighties by Elaine Scarry: The Body in Pain: the Making and Unmaking of the World. It's largely about torture and the reduction of the person to the body. I think it's an important book in really understanding the nature of power and control. I think it obliquely influenced some of the ideas in my first novel.

Getting back to the mentor discussion - I think the good mentor needs to be expert in their field, and available to answer questions, be able to avoid being judgmental, without doing away with the ability to provide constructive feedback (requiring sound judgement).

The group associated with this blog site is a network of authors who read each other's work and discuss various elements of working on a book-length writing project. We are all learning to become mentors to support one another in our work. I would be interested in any ideas on how we can make this work well for us all.

Published on June 26, 2013 20:15

June 24, 2013

Finding or Losing the Plot...

We had productive fun at Annabel Smith's plotting workshop on Saturday, with lively discussion around what it was that drew us into a novel, and what pulled us forward and compelled us to keep reading. We discussed masculine and feminine approaches (masculinist and feminist?) the linear and the circular, singularly or multiply climactic, and we did practical exercises exploring our current projects in the context of these exercises.

We had productive fun at Annabel Smith's plotting workshop on Saturday, with lively discussion around what it was that drew us into a novel, and what pulled us forward and compelled us to keep reading. We discussed masculine and feminine approaches (masculinist and feminist?) the linear and the circular, singularly or multiply climactic, and we did practical exercises exploring our current projects in the context of these exercises. Annabel explored the what and why of the novel, referencing articles from here, here, and here.

I'm always in two minds about workshops (at least two minds). At their best they can help break a deadlock and stimulate a surge in writing and a renewed level of excitement in what I am doing. (I tend to work at it regardless, but it's better and I'm more productive when I feel excited about the process). At the other end of the scale, workshops can become an end in themselves, an endless pursuit of information which is seldom directly applied to the project at hand. That's not a necessarily bad thing if it leads to a useful shift in understanding. I think no learning is wasted - it's all recycled, and often the long way round is the most scenic. Sometimes when I'm in the mood, I even book into workshops without knowing what they are going to be about. At the moment I've given myself a fairly tight schedule, so I was pleased that this workshop was immediately relevant, and my time was so well-spent.

Why?

The presenter was flexible in her approach and encouraged and engaged in the discussion around the pros and cons of plotting rules. It was a true exploration of ideas rather than a set formula approach to plotting - although structure was presented as a series of helpful exercises. What I found was that by going through the process of thinking about the various elements of story development, my own project became clearer, and the trajectory of the story became more developed in my imagination.

At the same time it reminded me that I have my own permission to live in uncertainty when it comes to writing a story. It can go in any one of so many directions, and the emphasis and story will change as the writing materialises. I feel that writing is a process of seeking a kind of truth through reconciling the conscious, rational mind with the intuitive, and by understanding that without some ability to step back and look at structure a story is impoverished. It is similarly impoverished when we write without emotion, passion, and a certain willingness to put our thoughts - or not our thoughts - (as words) on the line. In the bumpy and twisted terrain of novel-writing, by placing both hands on that steering wheel, we're more likely to keep our car on the road.

Published on June 24, 2013 20:48

June 21, 2013

Well, well... new blog site launched, and no messing about with trivia

A friend has sent me a link to his recently launched blog site, and if you have an interest in musings around the inevitable, and yet strangely avoided, topic of death, this post is one that I would highly recommend. It took a while to get the blog up and going, but has been worth the wait. Maarten has promised to send a couple of paragraphs to introduce himself to readers of this blog (a bit further down the track) but in the interim, you might like to take a look at what the site has on offer.

A friend has sent me a link to his recently launched blog site, and if you have an interest in musings around the inevitable, and yet strangely avoided, topic of death, this post is one that I would highly recommend. It took a while to get the blog up and going, but has been worth the wait. Maarten has promised to send a couple of paragraphs to introduce himself to readers of this blog (a bit further down the track) but in the interim, you might like to take a look at what the site has on offer.

Published on June 21, 2013 18:41

June 18, 2013

Episode Fifteen, and a little explanation which may or may not clarify things!

This is the last of the first draft writing I did for my abandoned post-apocalyptic satire. Normally I wouldn't publish creative writing in such an unfinished state, but this is a blog, and it provides an idea of one writer's start point on a manuscript (with some concurrent light editing). I'm not sure if, or how much, of this will be useful to others, but there it is, an example of a start, a bit like the first exploratory rehearsal of some scenes in a play. I might return to this story in the future, but for now it will be put away. My feeling is that the piece of writing is about a third of the way through a first draft (there are a few other bits and pieces) and that if I completed it, much of what has been posted here would ultimately be left on the cutting room floor. I don't know if there are any unbreakable rules when it comes to how to write a novel, or how long it should take. Any creative process is, by definition... well, creative. A creative writer needs to be comfortable with uncertainty. (Maybe they don't.) Will this one be finished? (I'll come back to it. In time.) When will it be finished? How do I know if something is finished? I will be starting work on my new project on July 1st and will be working solidly on that for the next year to get the first draft finished and then another year and some to bring it to publication standard. A question that might be worth asking is: what is publication standard for a novel (as distinct from a blog)? Beyond the obvious proof reading, agreeing on the state of being finished is quite a subtle thing. I don't know how to tell whether something is finished, other than to use my own intuition or instinct, to decide whether it makes some sort of emotional/intellectual sense (or not), and, as my editor once mentioned, to see if the writing is at the point at which my urge to keep changing things has ceased (or when I consistently begin to change things and then change them back). My usual approach to writing is to keep working on it within an inch of its life, which is why I have found a blog so useful as a freeing-up device. The novel needs more than a blog, and less than 'within an inch of its life' - that excessiveness that overworks a piece of writing so that it no longer breathes. Nothing human-made is perfect (an impossible concept to get one's head around when it comes to work that involves self and other observation, emotion and intellect combined with whatever it is that is mysteriously, and sometimes accidentally created by the choice and placement of words in a certain way) and I do find Leonard Cohen's Anthem so reassuring in this regard, not just for writing but for life. Not just for life, but for writing. The song has as many meanings as people listening I suppose, but it reminds me to accept that I have done the best I can for now, and accept what I do, and have done, as beautifully imperfect in its own way. (I've put the link to the You Tube clip there, just so you can take a break and enjoy his beautiful song!) For me (and I am forever emerging, rather than emerged, as a writer - still struggling from my chrysalis - an ongoing metamorphosis) for me, bits of a novel come from all over the place. A scene might be triggered by an image, a formal writing exercise at a workshop, a painting, documentary, road trip, conversation, passage of music, or (most often) a random (rogue?) idea. When I am working on something I prime myself to live within the story (I have to work on it a bit every day for this to happen) and trust that even if something that comes to me as a random and seemingly unconnected line of thought or bit of writing, it can ultimately be useful (either as content or subtext). Accidental occurrences open up my imagination and break me out of a confining loop of thinking that would otherwise return only what I know. Daydreaming, curiosity and an openness to discovery is, I think, the key. When I was studying theatre, the main rule to remember for group improvisations, was not to block ideas. I had to learn to relinquish control, not to force ideas into a preconceived template - had to be willing to go in another direction, even if it ended in the confinement of a cull-de-sac. One could always backtrack. Or start again from a different place. I suppose stamina is needed. Perseverance. But only in a non self-defeating kind of way, not beating up on oneself. Am I having fun yet? Freedom. I refuse to place unnecessary restrictions on myself. Structure maybe, restrict possibilities for expression - no. I say yes - and no. Since attending the Perth Writers Festival this year I now have Margaret Atwood's word for it - plork (plerk?) - a combination of play and work.

This is too long and self-indulgent for a blog post, possibly, but anyway I hope you enjoy this last little bit of random, slightly tidied up, imagining.

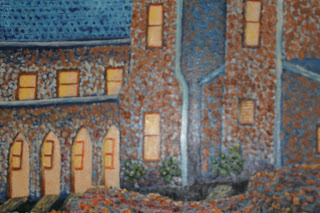

My dad did this painting in 1971 - depiction of an 'asylum' - is this the compound?

My dad did this painting in 1971 - depiction of an 'asylum' - is this the compound?Reporting back

The compound meetings to discuss strategic planning occurred on the first and third Saturday evenings of each month. Griselda the Third sat at the hearth and listened with her eyes closed to the goings-on occurring at the compound table. No-one could remember Griselda the First and Second, but the implication that Griselda the Third occupied the position as a kind of birthright was not lost on anyone, as it was part of the lengthy induction that all served. Griselda was the Great Mother, a large woman in a voluminous green dress. She had strong, weathered hands and a strangely smooth face. Her hair tumbled down her back in soft waves and shone red and gold where the firelight caught it. She smelt of peppermint and rosewater.

Before the meeting, each teacher came separately to kneel before her and receive her blessing for Truth, Courage and Creativity. After the blessing, Mother would hold out her arms, ‘Now give me a big hug and tell me that you love me,’ she’d say, and each in turn would fall into her arms.

She had a soft spot for Terry, and tonight when he knelt at her feet with his head bowed down, she lifted his face in her hands and studied his expression.

‘Change,’ she said, ‘is life. Remember that. Do not hold on too tightly Terry. I know you like to control the direction, but you can destroy the fragile possibilities if you don’t open your heart. Look deeper. Now give me a big hug and tell me that you love me.’

Terry fell into her arms and said, ‘I love you Mother’.

‘There’s a good boy,’ she said. ‘There’s a good boy.’

Her first words to him this evening were mysterious and difficult to fathom. Later, in his single room, he would write them down and try to analyse their meaning. He rehearsed them in his head. ‘Change is life. Do not hold on too tightly. Destroy fragile possibilities if don’t open heart. Look deeper.’

‘And Terry, pop another lintel on the fire would you, there’s a good boy. It’s cold this evening.’

When the meeting proper began, each child in each family was discussed and their progress reported. Any odd or unusual behaviour was discussed in great length with regard to the costs and benefits to the society that the person would ultimately inhabit, the society that Mother had seen in her famous vision. No decisions were made at this stage. Everything was laid out flat and turned inside out, like an animal skin pegged to dry in the sun. Moulding a life was like trying to build a puzzle. All the pieces needed to be in place before the details of the picture emerged fully. Sometimes the picture shifted right there in front of the eyes. The guardians of society had to be ready for constant improvement as decreed by the visions that were constantly being sent from the great unknown.

Griselda was the ultimate guardian of that picture. She was building it, piece by piece, in her mind’s eye. She had the gift of the overview; the understanding that diversity is connected to strength, and that strength, and survival, could not be separated from ethical sensibilities. The good of the whole was paramount, but compassion towards the individual was maintained wherever possible. Only Griselda held a full understanding, although others were being schooled. Only those with the gift would be able to reach such heights of enlightenment. Right now the knowledge was being passed on by her to her daughters.

*

The women were already around the table, some seated and some standing together in small groups chatting when Bob arrived. Bob always found it somewhat daunting to walk into this, the subtle glances as they thought whatever it was that they were thinking, although how they could have anything left to wonder about, he did not know. Each and every one of them knew him a little too well, but they were never satisfied. These women were always wanting, always vying for his attention.

He was past optimal breeding age, so had been relieved of that obligation at least five years before. Now he had no more viable seed save for that stored in the bank. They stopped collecting when he turned thirty-seven. That was close on twenty years of service. He was already exhausted. Little did he know it would be just the beginning of his public service.

On the day of his completion, there were women lined up around the block with gifts of food and drink and drugs. They called it ‘The Release’. From that day he was, as they said here, a free man, although freedom from his own perspective was debatable. What ‘The Release’ really meant was that they were free to pursue him, and pursue him they did.

He hated it. Even in the meetings, he hated the furtive glances, the secret smiles as one or another recalled an encounter with him in the dark in his room, or in the candlelight, in hers. The fumbling darkness was at his request. He hated the idea of the voyeurs watching on screens, participating, scooping up every little bit of his being.

What was it all about, he wondered? He couldn’t directly give them children. There was still the potential in the lab, if that’s what they wanted from him. They wouldn’t have wanted that life anyway, isolated in their houses, unaware of the bigger picture, unable to do what they seemed to like most of all, which was to talk endlessly with one another about the most trivial of things. And they found comfort in each other’s arms too, here, he knew that well enough, although they were called upon to be discreet. Griselda knew of the dangers too, of rivalry and the emotions that it arouse, and ensured that the group bonding overwhelmed individual longing. Passion was allowed to be expressed, but then it was discussed and deconstructed until it lost all its power over them.

‘The power of women is in the collective,’ she would tell them. ‘Never forget this. It was lust for individual gain that collapsed the world of men. This must never happen again.’ And they would always say ‘Praise be to Griselda,’ although whether they felt it, or not, or whether they believed what she said, was difficult to say. They responded so automatically that the words they said probably never even reached awareness. And yet, awareness was valued above all else. They were not to take what was offered for granted, whether it was the affections of another, or the earth’s bounty. To do so would lead to greed, and it was greed that led them to the ailing earth that they had inherited from their foremothers and their forefathers. They must ensure that this never happened again. That was the true meaning of their ritual.

At the table they always began with an ode to something that the earth had offered to them. Today a harvest of plums piled into a basket had been placed in the middle of the table for contemplation and ultimate consumption. At each meeting someone was charged with saying the grace. Today it was the turn of a small, quiet woman called Zelda who was also to chair the meeting. She stood and opened her arms to them all, looking at each individually. She had been practicing this, her big moment, in her room with the light out. The dark surveillance had picked it up in any case, to Griselda’s amusement. Zelda began to speak with a quavering voice, full of infatuation for the earth and what it had to offer.

‘Praise,’ she said. ‘Praise to the plum.’ She paused to give all present, time to contemplate the plum. Then she began in earnest. ‘Oh plum, we praise thee. We praise thy soft, round surface. We praise thy tender selflessness. We praise thy givingness. We praise thy fecundity. We praise the way thou springest into tree so freely and givest of thy fruit so willingly and mindest not the gathered or the ungathered that spoil beneath thy green branches. We praise thy gentleness, thy generosity to feed the hungry mouth and the hungry soul. We praise the life within, the life shared, thy forbearance. We praise thee plum. We praise thee. We praise thy ordinariness and thy uniqueness, thy depths and surfaces, thy value, thy love of all that lives. And all that dies.’

There was silence around the table as all contemplated the plum and what it meant. Zelda picked up the basket and took it then for Griselda’s blessing.

‘Lovely,’ she said. ‘I’ll have two.’ She chose two perfect specimens, laid one in her ample lap and bit into the other, chewing thoughtfully, her eyes closed to help her experience the ecstasy. When at length she swallowed, she waved her arm magnanimously and said, ‘Let the feasting begin!’

Zelda brought the basket back to the table and offered it to the two men present, to Terry and Bob. Then each of the women took a plum, and ate in slow and sensuous reverence. Zelda allowed the red juice to trickle from her mouth and over her chin. The stain would help to remind her of this moment when she became one with the earth and offered up her blessing. Her turn would not come around for another year and she wanted to extend the magical reality of this moment for as long as she could.

But the moment, as all moments, ended, and all reluctantly turned to the business at hand. Half way through the business of the day, the bush experiment reporting began. ‘Changes in Circumstance’ was at the top of the list.

‘What of the boy Dalyon?’ Zelda asked. Her voice was breathy and rapid, as if she was batting a shuttlecock away from her, or a series of shuttlecocks.

Alba, a short woman with shoulder-length mousy-coloured hair, raised her hand. ‘He has settled in well with the girl Jilda and the boy Lucan,’ she said. ‘He is learning the art of bush survival and continuing to develop his gift. Mother may wish to see the visual history at some time?’

‘The girl Jilda has good protective instincts for her charge does she not?’ said Zelda, channeling Mother Griselda.

‘Oh yes. She was located on screen only six months ago with her young brother, and both were in robust health. Apparently they had been living in the Q bunker that had been thought to be abandoned.’ Alba flicked through her notes. ‘Oh yes, and the boy Dalyon is active and healthy still, I should mention that, and does not seem to be pining for his mother, or his cat.’

‘It will be interesting to see how the dynamics evolve. Leave him where he is for now and report any developments to me personally and without delay,’ Mother Griselda decreed from her large and comfortable chair at the hearth. ‘Moving on.’

‘Let the decision be noted,’ said Zelda. ‘To be reviewed?’

‘Two weeks,’ said Griselda, leaving Bob and Terry’s presence on the matter entirely redundant. Griselda must have sensed this, for she added, ‘And how did you go with the poor mother?’

‘Her final resting place was a shallow hole, unfortunately Mother,’ said Terry, ‘due to an impenetrable system of tree roots that went right through the yard. We didn’t want to damage the tree system, naturally.’

‘Never mind,’ said Griselda. ‘Make a note to avoid using the house again for now. What about the cat?’

‘Disposed of,’ said Bob.

‘Good. They can get very bad in the bush. Well done. Next.’

Published on June 18, 2013 19:54

June 17, 2013

Annabel Smith's Workshop on Plotting next Saturday

Annabel Smith will be running a workshop on Novel Plotting on Saturday 22nd June from 1.30- 4.30pm at Mattie's House, FAWWA Allen Park Precinct, Swanbourne.The workshop will equip participants with the tools for plotting a novel. It is suitable for people at any stage of a writing project. Learn to understand the two sides of the plot ‘coin’ What? And why?Create a plot outline for your novel using an eight-point story arc structure. Create a one sentence summary ideal for pitching to agents and publishers.Finally map your work-in-progress against the 8 elements that create the ‘why’ of a novel and an 8-point story structure; identify gaps and missing elements.The workshop is $30 for FAWWA members and $35 for non-members.

Annabel Smith will be running a workshop on Novel Plotting on Saturday 22nd June from 1.30- 4.30pm at Mattie's House, FAWWA Allen Park Precinct, Swanbourne.The workshop will equip participants with the tools for plotting a novel. It is suitable for people at any stage of a writing project. Learn to understand the two sides of the plot ‘coin’ What? And why?Create a plot outline for your novel using an eight-point story arc structure. Create a one sentence summary ideal for pitching to agents and publishers.Finally map your work-in-progress against the 8 elements that create the ‘why’ of a novel and an 8-point story structure; identify gaps and missing elements.The workshop is $30 for FAWWA members and $35 for non-members.

Published on June 17, 2013 00:40

June 16, 2013

Thank you Annabel Smith

We had a great session at the Book Length Project Group yesterday with author Annabel Smith. Annabel generously shared her experience of writing with us, and answered questions regarding the craft and the publishing world. We have a very strong writing community in this part of the world, and a strong blogging community that reaches out to the wider global writing community. Check out Annabel's blog here.

We had a great session at the Book Length Project Group yesterday with author Annabel Smith. Annabel generously shared her experience of writing with us, and answered questions regarding the craft and the publishing world. We have a very strong writing community in this part of the world, and a strong blogging community that reaches out to the wider global writing community. Check out Annabel's blog here.

Published on June 16, 2013 18:04

June 12, 2013

My Talk at the Armadale Library June 19

Picture by Matt Biocich Hi there! I'll be going along to the Armadale Library on June 19 at 7pm to talk about my book and writing. It's a free event, so if you are in the vicinity and would like to come along, would love to see you there. Click on this link to find out more

Picture by Matt Biocich Hi there! I'll be going along to the Armadale Library on June 19 at 7pm to talk about my book and writing. It's a free event, so if you are in the vicinity and would like to come along, would love to see you there. Click on this link to find out more

Published on June 12, 2013 17:49

June 11, 2013

Episode Fourteen

The compound

It was three days since Bob and Terry had returned. Life off the road was tedious by comparison, but took no effort as such.

It was three days since Bob and Terry had returned. Life off the road was tedious by comparison, but took no effort as such.

Number 27 was the only room with the door ajar, not that it mattered. Everyone and anyone could be seen at any time on the screens, so nobody with her door shut would think to misbehave, even if misbehavior were waved right in front of her nose, even if she wanted to.

Bob sat on his perfectly flat single bed, smoking. It didn’t matter. He’d passed optimal breeding age anyway and all his seed had been long-since been collected and utilized. He was indulged as he wished, and he did wish to indulge, with old-fashioned comforts – alcohol in all its strengths and varieties, tobacco, hash, ice, Es and the rest of the quaintly named old mind-altering substances, along with their antidotes when work needed to be done, or when things got out of hand.

All this stuff didn’t make him any different, or change him, as they used to think. There was nothing to change but change itself. The idea that Bob was somehow separate from his changing body or from the sum of the substances that he ingested or inhaled was nonsensical. He was what he was, and he did what he did, and one day when he had served his function, in terms of the general consensus, he would be no more. The end would come gently, humanely, in a way that he could orchestrate for himself, and at a time of his choosing. And there, of course, was the rub, as someone in a famous play of antiquity had once put it. In the end, apart from sensual pleasure, what was there?

He imagined the Great Mother protesting at this point. Women seemed to gain pleasure from community, self-sacrifice and social approbation, which was their prerogative as the privileged majority, and which, he supposed, gave them more of a feeling of connection to a world that they imagined continuing after they had gone. But all that just seemed like a delusion to him. How did they know what was to come in a time of such uncertainty? Did they really think they could control the bigger picture? One asteroid and it would all be over. What did it matter anyway?

The irony of his situation, of all possible situations, did not escape him. Once, when he was younger, he’d spent one or two days buried in what they used to call depression, until the doctor fixed him.

‘There are more things in heaven and earth…’ she said, and offered Bob a swig from her flask. Bob took a gulp. It burnt all the way down.

‘Keep it,’ the doc had insisted when he went to hand it back. ‘Plenty more where that come from. Now don’t you go worrying your pretty little head about anything.’

She knelt down, took his face in her hands and kissed him soundly, struggled her substantial body back to its feet, and left him with the flask, a refill and a packet of cigarettes to go with the matches that he had already collected.

‘Just don’t spread it around,’ she said as she turned back for one last leer, at the doorway.

When he was younger, he used to wonder if he was more in a position of privilege, or pressure. Bob smiled at the memory of his younger self. The question seemed so meaningless now. He couldn’t even remember what was in his mind when he used to think that. He remembered that he used to wonder what it would have been like when humans spread like a plague across the earth and when men and women were more or less conceived and born in equal numbers – back in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for example. It wasn’t all that long ago – seventy or eighty years – still with everything that had happened in the interim, it could have been eons. He was something of a throwback he guessed. A hundred years or so of assisted evolution hadn’t really done anything to change his fundamentals. They were too cautious, these women, when it came to making change happen.

So here he was, an old-fashioned man not fitting in very well in a new-fashioned society. He should have been born somewhere in the twentieth century. He could have blended in then, maybe had a relationship for a while, like they used to, one-on-one, serial monogamy. There was something pure and honourable about the whole idea of that kind of sexual repression. There was a certain security in those boundaries that allowed for more freedom than the eventual free-for-all that was encouraged now. Still. What he would do with that boundaried freedom, or even what it really signified, he had no idea.

It was three days since Bob and Terry had returned. Life off the road was tedious by comparison, but took no effort as such.

It was three days since Bob and Terry had returned. Life off the road was tedious by comparison, but took no effort as such. Number 27 was the only room with the door ajar, not that it mattered. Everyone and anyone could be seen at any time on the screens, so nobody with her door shut would think to misbehave, even if misbehavior were waved right in front of her nose, even if she wanted to.

Bob sat on his perfectly flat single bed, smoking. It didn’t matter. He’d passed optimal breeding age anyway and all his seed had been long-since been collected and utilized. He was indulged as he wished, and he did wish to indulge, with old-fashioned comforts – alcohol in all its strengths and varieties, tobacco, hash, ice, Es and the rest of the quaintly named old mind-altering substances, along with their antidotes when work needed to be done, or when things got out of hand.

All this stuff didn’t make him any different, or change him, as they used to think. There was nothing to change but change itself. The idea that Bob was somehow separate from his changing body or from the sum of the substances that he ingested or inhaled was nonsensical. He was what he was, and he did what he did, and one day when he had served his function, in terms of the general consensus, he would be no more. The end would come gently, humanely, in a way that he could orchestrate for himself, and at a time of his choosing. And there, of course, was the rub, as someone in a famous play of antiquity had once put it. In the end, apart from sensual pleasure, what was there?

He imagined the Great Mother protesting at this point. Women seemed to gain pleasure from community, self-sacrifice and social approbation, which was their prerogative as the privileged majority, and which, he supposed, gave them more of a feeling of connection to a world that they imagined continuing after they had gone. But all that just seemed like a delusion to him. How did they know what was to come in a time of such uncertainty? Did they really think they could control the bigger picture? One asteroid and it would all be over. What did it matter anyway?

The irony of his situation, of all possible situations, did not escape him. Once, when he was younger, he’d spent one or two days buried in what they used to call depression, until the doctor fixed him.

‘There are more things in heaven and earth…’ she said, and offered Bob a swig from her flask. Bob took a gulp. It burnt all the way down.

‘Keep it,’ the doc had insisted when he went to hand it back. ‘Plenty more where that come from. Now don’t you go worrying your pretty little head about anything.’

She knelt down, took his face in her hands and kissed him soundly, struggled her substantial body back to its feet, and left him with the flask, a refill and a packet of cigarettes to go with the matches that he had already collected.

‘Just don’t spread it around,’ she said as she turned back for one last leer, at the doorway.

When he was younger, he used to wonder if he was more in a position of privilege, or pressure. Bob smiled at the memory of his younger self. The question seemed so meaningless now. He couldn’t even remember what was in his mind when he used to think that. He remembered that he used to wonder what it would have been like when humans spread like a plague across the earth and when men and women were more or less conceived and born in equal numbers – back in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for example. It wasn’t all that long ago – seventy or eighty years – still with everything that had happened in the interim, it could have been eons. He was something of a throwback he guessed. A hundred years or so of assisted evolution hadn’t really done anything to change his fundamentals. They were too cautious, these women, when it came to making change happen.

So here he was, an old-fashioned man not fitting in very well in a new-fashioned society. He should have been born somewhere in the twentieth century. He could have blended in then, maybe had a relationship for a while, like they used to, one-on-one, serial monogamy. There was something pure and honourable about the whole idea of that kind of sexual repression. There was a certain security in those boundaries that allowed for more freedom than the eventual free-for-all that was encouraged now. Still. What he would do with that boundaried freedom, or even what it really signified, he had no idea.

Published on June 11, 2013 19:52

June 9, 2013

An allegory from Patricia Johnson

I am wondering if we are seeing a resurgence of interest in fairy stories and allegories. I find something very powerful about this literary form, and would be interested in any comments around this. Pat Johnson has kindly given permission for me to publish this one of hers on the blog. It comes from "Tales from the Dark Mountain".

Enjoy!

Pat JohnsonThe Coffee Bean Babies

Pat JohnsonThe Coffee Bean Babies

Far away on the other side of the world a village rests on the face of a dark mountain. Early every morning when the villagers awake from their night time dreams they hurry out into the sunlight. Dressed for a day of work, they walk together to their fields.

Today they get a surprise; the mountain looks different. It is covered with crawling things that look like coffee beans. They are everywhere up and down the side of the mountain. The villagers wonder what has happened. Then they hear a baby’s cry. They are little brown babies, cute and plump and solid, crawling on the mountain.

They are not really crying. The sound is more like babbling. The babies seem very happy but none of the villagers know where they have come from. The villagers have their own babies; they don’t need any more although they are very fond of babies. There are no adults with the babies, not one to feed them or look after them.

Soon all the children are in the fields playing with the new babies, swinging them in the air, and cuddling them; watching and talking to and loving them. The babies do not pay much attention to the village children who are pushing and pulling them about, lugging them around to show their friends. Those coffee bean babies are just happy. But when they get the chance, they want to crawl. They are exploring everywhere.

Yes, now the villagers see that there is something familiar about them – they remember that whenever babies come, something unusual happens. They can only wait and see. As they look along the mountainside the babies are crawling through their crops and fields.

The sky turns black and the babes stop, afraid. Thunder rumbles and rain pours down. When the sky clears, the villagers notice that now the babies have wings, heavy, solid clumsy wings that will never fly.

The fields are full of crawling babies, babies crawling through the cabbages and potatoes, and the carrots and the pumpkin, and the wheat, pulling up all the roots as they drag their heavy wings. The villagers are stunned. As they slide over the wet ground they try to figure out what they should do. Everyone is worried that they will have nothing to eat if the babies ruin all their crops. But how to remove them? They cannot rake them up and push them to the side; they will not stay.

The villagers who have always loved babies are beginning to hate them. They start to run. They run away from the babies, away from their fields. They run because they are confused and afraid; afraid that they might hurt the babies and they know that they should not do that. They know they can only wait and see. But they are so angry that the babies are destroying all the food they have planted, they run down the mountainside, run away to get to a place that feels safe.

When they are far down the mountain, they look back and see the babies in the distance. The little babies are like a colony of ants on the mountainside. Now the villagers can think. What will happen if it rains again? Then, there is a long deep rumble, like thunder, but the sky is clear. All the men and women of the village are in the valley, but their own children are still up there playing. When they look upward, they see their own children moving around among the crawling babes.

There is another, very loud rumble. The children are startled and they start to run down the mountain to their parents. As they run they feel the ground moving underneath them.

The mountain itself is trying to shrug off the itchy, annoying little insects that are crawling around on its surface. The skin of the mountain is itching. Its rumbles are getting louder and louder. The trees are shaking loose and falling down. Rocks are tumbling. The whole mountain explodes. The babies are thrown into the air, crashing into each other.

Meanwhile, the children have made it down the mountain and are with their parents again, very glad to be there. In silence they strain their eyes to see the babies, who have stopped crashing and whose heavy wing cases are falling to the ground.

Then the villagers hear a faint buzzing. Fine gossamer wings are bursting out of the babies shoulder blades, allowing them to fly and setting them free. The excited babies buzz loudly. They group together in a ring above the mountain. They are beautiful! The sun breaks through changing them from brown to gold. The light bouncing off the golden babies gives out a glare that hurts the eyes.

All the trees and rocks, the moss and streams, everything that the mountain had thrown off, is settling back down. Everything is returning to the mountain. Even the village itself, tossed high and far into the clouds, is finding a new spot to rest. Nothing is as it was. And as things nestle into different and awkward positions, the sun continues to blaze brightly on the babies, a hovering ring of gold.

The villagers are beginning to recover. They think the mountain may have become quiet once more. They start to trek upward to where the village teeters back and forth. As they walk, shards of gold fall from the sky, decorating the fields. Looking up, they see the babies disintegrating, breaking apart and dropping silently, as softly as snowflakes drifting though the air. The falling gold has no weight; it floats quietly until it settles on the ground. But as soon as it settles, the gold is sucked below the surface. Rapidly down it goes, deep into the cold centre of the mountain. The ground rumbles and shifts again, shrugs and resettles.

The villagers trudge upward, unworried because the mountain has restored itself and the mountain is their home. It has all happened very fast. The little coffee bean babies are gone. The villagers didn’t have to do anything. They didn’t know what was happening or what to do but it didn’t matter. Everything is okay again – but different. They head toward their village which is still tottering back and forth, up and down, left and right. They watch as it tilts to one side, then topples right over! They climb upward. Tomorrow they will start fixing, repairing and rebuilding.

Far into the heart of the mountain, they go. When they have gone far enough they lay down and cover themselves in furs and go to sleep deep in the earth where it is dark and quiet. They are part of the mountain that does not change. And as they sleep they grow strong.

Enjoy!

Pat JohnsonThe Coffee Bean Babies

Pat JohnsonThe Coffee Bean Babies Far away on the other side of the world a village rests on the face of a dark mountain. Early every morning when the villagers awake from their night time dreams they hurry out into the sunlight. Dressed for a day of work, they walk together to their fields.

Today they get a surprise; the mountain looks different. It is covered with crawling things that look like coffee beans. They are everywhere up and down the side of the mountain. The villagers wonder what has happened. Then they hear a baby’s cry. They are little brown babies, cute and plump and solid, crawling on the mountain.

They are not really crying. The sound is more like babbling. The babies seem very happy but none of the villagers know where they have come from. The villagers have their own babies; they don’t need any more although they are very fond of babies. There are no adults with the babies, not one to feed them or look after them.

Soon all the children are in the fields playing with the new babies, swinging them in the air, and cuddling them; watching and talking to and loving them. The babies do not pay much attention to the village children who are pushing and pulling them about, lugging them around to show their friends. Those coffee bean babies are just happy. But when they get the chance, they want to crawl. They are exploring everywhere.

Yes, now the villagers see that there is something familiar about them – they remember that whenever babies come, something unusual happens. They can only wait and see. As they look along the mountainside the babies are crawling through their crops and fields.

The sky turns black and the babes stop, afraid. Thunder rumbles and rain pours down. When the sky clears, the villagers notice that now the babies have wings, heavy, solid clumsy wings that will never fly.

The fields are full of crawling babies, babies crawling through the cabbages and potatoes, and the carrots and the pumpkin, and the wheat, pulling up all the roots as they drag their heavy wings. The villagers are stunned. As they slide over the wet ground they try to figure out what they should do. Everyone is worried that they will have nothing to eat if the babies ruin all their crops. But how to remove them? They cannot rake them up and push them to the side; they will not stay.

The villagers who have always loved babies are beginning to hate them. They start to run. They run away from the babies, away from their fields. They run because they are confused and afraid; afraid that they might hurt the babies and they know that they should not do that. They know they can only wait and see. But they are so angry that the babies are destroying all the food they have planted, they run down the mountainside, run away to get to a place that feels safe.

When they are far down the mountain, they look back and see the babies in the distance. The little babies are like a colony of ants on the mountainside. Now the villagers can think. What will happen if it rains again? Then, there is a long deep rumble, like thunder, but the sky is clear. All the men and women of the village are in the valley, but their own children are still up there playing. When they look upward, they see their own children moving around among the crawling babes.

There is another, very loud rumble. The children are startled and they start to run down the mountain to their parents. As they run they feel the ground moving underneath them.

The mountain itself is trying to shrug off the itchy, annoying little insects that are crawling around on its surface. The skin of the mountain is itching. Its rumbles are getting louder and louder. The trees are shaking loose and falling down. Rocks are tumbling. The whole mountain explodes. The babies are thrown into the air, crashing into each other.

Meanwhile, the children have made it down the mountain and are with their parents again, very glad to be there. In silence they strain their eyes to see the babies, who have stopped crashing and whose heavy wing cases are falling to the ground.

Then the villagers hear a faint buzzing. Fine gossamer wings are bursting out of the babies shoulder blades, allowing them to fly and setting them free. The excited babies buzz loudly. They group together in a ring above the mountain. They are beautiful! The sun breaks through changing them from brown to gold. The light bouncing off the golden babies gives out a glare that hurts the eyes.

All the trees and rocks, the moss and streams, everything that the mountain had thrown off, is settling back down. Everything is returning to the mountain. Even the village itself, tossed high and far into the clouds, is finding a new spot to rest. Nothing is as it was. And as things nestle into different and awkward positions, the sun continues to blaze brightly on the babies, a hovering ring of gold.

The villagers are beginning to recover. They think the mountain may have become quiet once more. They start to trek upward to where the village teeters back and forth. As they walk, shards of gold fall from the sky, decorating the fields. Looking up, they see the babies disintegrating, breaking apart and dropping silently, as softly as snowflakes drifting though the air. The falling gold has no weight; it floats quietly until it settles on the ground. But as soon as it settles, the gold is sucked below the surface. Rapidly down it goes, deep into the cold centre of the mountain. The ground rumbles and shifts again, shrugs and resettles.

The villagers trudge upward, unworried because the mountain has restored itself and the mountain is their home. It has all happened very fast. The little coffee bean babies are gone. The villagers didn’t have to do anything. They didn’t know what was happening or what to do but it didn’t matter. Everything is okay again – but different. They head toward their village which is still tottering back and forth, up and down, left and right. They watch as it tilts to one side, then topples right over! They climb upward. Tomorrow they will start fixing, repairing and rebuilding.

Far into the heart of the mountain, they go. When they have gone far enough they lay down and cover themselves in furs and go to sleep deep in the earth where it is dark and quiet. They are part of the mountain that does not change. And as they sleep they grow strong.

Published on June 09, 2013 20:19

Iris Lavell's Blog

- Iris Lavell's profile

- 3 followers

Iris Lavell isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.