Rivera Sun's Blog: From the Desk of Rivera Sun, page 9

March 6, 2020

10 Ways To Make the Change You Want

By Rivera Sun

As the editor of Nonviolence News, I collect 30-50 stories of nonviolence in action each week. Each story offers us a take-away lesson for our own work for change. These lessons offer us best practices and pro-tips from our fellow human beings who are working for change around the world. We can learn from their successes and their set-backs. We can let their brilliance inspire us and we can stand on their giant shoulders as we strive to make a difference in our own way.

Nonviolence is one of humankind’s greatest achievements – and it’s just getting started. It’s up to us to take it further, use it more skillfully, and discover how nonviolence can help us be -and make – the change we wish to see in the world.

Here are ten pointers for change makers from this week’s news:

1. The Ripple Effect of the LA Teachers Strike

In the wake of last year’s strike by Los Angeles teachers, random searches of students are coming to an end district wide — landing a blow against racism and racial profiling in schools. The LA teachers strike was a successful campaign for a set of economic justice goals, but its impact continues, showing how powerful strikes can have an on-going effect. Sometimes, this is true even when campaigns don’t succeed in achieving their stated goals. The 2011 Occupy protests didn’t end inequality, but they did break the issue through mass consciousness in an unprecedented way that continues to affect everything from wages to presidential campaigns.

2. #NotAgainSU Students Show Why Making (And Revising) Demands Is Important

Amidst hate crimes, Syracuse University students are pressing for major changes in the institution’s approach to diversity and inclusivity. An earlier campaign created and achieved 9 out of 12 demands. After that success, they revised some of the remaining demands, added a new set, and launched a new occupation of buildings. The checklist of demands shows clearly how direct action is succeeding, where the university is dragging its feet, and what work remains to be done. Demands can be powerful – as these students are proving.

3. Climate Victory Gardens Embody the Power of Constructive Program

Gandhi would appreciate the thousands of people who are fighting climate change one backyard garden at a time. It’s a constructive program – a type of action that everyone can do, builds strength and community, and addresses the problem all at the same time. Constructive programs, like the 2,000 Climate Victory Gardens, have the added benefit of involving people who might not otherwise get involved in the movement. Plus, you get fresh veggies. What’s not to love?

4. Sunrise Activists Tell Us To Quit Playing By the Rules

More than 150 middle-and-high school students from across the United States gathered to demand that senators “stand up or step aside” on the climate crisis. “We’re done playing by the rules,” they say. Their boldness reminds us that when the rules of the game are meant to make some people the perpetual winners and others the losers, it’s time to quit playing by the rules – and perhaps it’s time to change the game entirely. Nonviolent action puts the ball in our court and gives us a whole different way to push for change than through conventional channels.

5.Spain’s Women’s Soccer Shows Us the Power of Organizing for Everyone Following the players’ strike in November, female soccer players in Spain have won the league’s first ever collective bargaining agreement and league-wide contracts. Their story shows the power of organizing for – and with – everyone instead of petitioning for individual pay raises. It’s a team sport, after all.

6. Extinction Rebellion’s “Lawngate” Shows How Property Destruction Can Backfire

The notorious climate emergency rebels stirred up controversy by digging up the lawn of Cambridge University. The press dubbed the blowback as “Lawngate.” Was “Lawngate” nonviolent direct action or vandalism? Did it serve the climate justice movement or backfire on Extinction Rebellion? Property destruction is often controversial both inside movements and among the general population. When considering its worth as part of an action, it’s important to consider how it will be perceived by your society. Will the reaction serve your cause . . . or detract from it? Did the property destroyed have a negative image which would make the public sympathetic, or was the action taken seen as simply inchoate destruction?

7. Red-state Utah’s Climate Crisis Plan Proves Speaking Beyond the Choir Matters:

In a surprising shift, Utah Republicans are supporting a plan that aims to reduce emissions over air quality concerns and global warming. “If we don’t think about it, who will?” they say. How did that happen? By talking “common cents,” economic sustainability of ski slopes, and clean air quality. When we’re organizing for change, it’s helpful to speak the language of the people we want to change, not our own framings and phrasings. After all, we’re convinced. It’s the other people we’ve got to persuade to make a shift.

8. Colombian National Strike Committee’s Renewed Protests Teaches Us to Go Beyond Single Actions

Colombians have been campaigning for change for months. They’ve used a wide variety of tactics, mobilized rotating sectors of the populace, and launched several waves of mass action. Why? Because single marches or one-up demonstrations aren’t enough. Real change comes from sustained, creative, strategic sets of actions designed to achieve specific goals, and then keep building.

9. Sudan Reminds Us to Protect Those Who Refuse to Hurt Protesters

Sudan recently had a successful nonviolent revolution. The victory did not come without sacrifice – more than 100 people were killed in just one of the violent crackdowns by the regime. Recently, they’ve been campaigning to protect soldiers who were fired for refusing to hurt the people. Why does this matter? Because it’s helpful to build allies with the very people who are ordered to crack down on your movement. And, it’s important to make sure that soldiers who refuse to hurt their people are rewarded, not punished. It sends an important message to their fellow soldiers, leaders, and others about the society’s expectations around mass movements.

10. Anti-Gentrification Fight Demonstrates Why Collecting Solutions Helps

Half the battle is finding a better option. The effort to halt and end gentrification recently shared a set of best practices for fighting gentrification, including everything from Community Land Trusts to Tenant Buy Options. The list highlights success stories, offers solutions to entrenched injustices, and comes in handy when you need to come up with an alternative for your community

These are just 10 of the 50+ stories in this week’s issue of Nonviolence News. There’s a lot to learn from our fellow human beings’ efforts toward peace and justice. If we pay attention, stay alert, and take notes, we might find our own work for change grows in power, strength, and wisdom.

__________________

Rivera Sun , syndicated by PeaceVoice , has written numerous books, including The Dandelion Insurrection . She is the editor of Nonviolence News and a nationwide trainer in strategy for nonviolent campaigns.

December 12, 2019

Beyond Changing Light Bulbs: 21 Ways You Can Stop the Climate Crisis

Image by Leonhard S from Pixabay

Image by Leonhard S from PixabayHere’s the good news: The debate is over. 75% of US citizens believe climate change is human-caused; more than half say we have to do something and fast.

Here’s even better news: A new report shows that more than 200 cities and counties, and 12 states have committed to or already achieved 100 percent clean electricity. This means that one out of every three Americans (about 111 million Americans and 34 percent of the population) lives in a community or state that has committed to or has already achieved 100 percent clean electricity. Seventy cities are already powered by 100 percent wind and solar power. The not-so-great news is that many of the transition commitments are too little, too late.

The best news? The story doesn’t end there.

We can all pitch in to help save humanity and the planet. And I don’t mean just by planting trees or changing light bulbs. Climate action movements are exploding in numbers, actions, and impact. Groups like Youth Climate Strikes, Extinction Rebellion, #ShutDownDC, the Sunrise Movement, and more are changing the game. Join in if you haven’t already. As Extinction Rebellion reminds us: there’s room for everybody in an effort this enormous. We all make change in different ways, and we’re all needed to make all the changes we need.

Resistance is not futile. As the editor of Nonviolence News, I collect stories of climate action and climate wins. In the past month alone, the millions of people worldwide rising up in nonviolent action have propelled a number of major victories. The University of British Columbia divested $300 million in funds from fossil fuels. The world’s largest public bank ditched fossil fuels and said it would no longer invest in oil and coal. California cracked down on oil and gas fracking permits halting new drilling wells as the state prepares for a renewable energy transition. New Zealand passed a law to put the climate crisis at the front and center of all its policy considerations (the first such legislation in the world). The second-largest ferry operator on the planet is switching from diesel to batteries in preparation for a renewable transition. Re-affirming their anti-pipeline stance, Portland, Oregon city officials told Zenith Energy that they would not reverse their decision, and instead would continue to block new pipelines. Meanwhile, in Portland, Maine, the city council joined the ever-growing list endorsing the youths’ climate emergency resolution. Italy made climate change science mandatory in school. And that’s just for starters.

Is it any wonder Collins Dictionary made “climate strike” the ?

Beyond planting trees and changing lightbulbs, here’s a list of things you can do about the climate crisis:

1. Join Greta Thunberg, Fridays for the Future, and the global Student Climate Strikes on Fridays.

2. Not a student? Join Jane Fonda’s #FireDrillFridays (civil disobedience is the latest workout fad; everybody looks good saving the planet).

3. Take to the field, like the students who disrupted the Harvard-Yale football game to demand fossil fuel divestment. You can’t play football on a dead planet, after all.

4. Stage an “oil spill” like these 40 members of Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard (FFDH) and Extinction Rebellion. They staged an oil spill in Harvard’s Science Center Plaza to call attention to the university’s complicity in the climate crisis.

5. Get in the way with city-wide street blockades like #ShutDownDC. People from an alliance of groups blockaded the banks and investment firms in the nation’s capital to protest the financing of fossil fuels, and the ways the banking industry drives the climate migration crisis while profiting from the devastation.

6. Rally the artists and paint giant murals to remind people to take action, like this skyscraper-sized Greta Thunberg mural in San Francisco.

7. No walls handy? Print out a scowling Greta and put it in the office to remind people not to use single-use plastic.

8. Crash Congress (or your city/county officials’ meetings) demanding climate legislation, climate emergency resolutions, and more. That’s what these climate justice activists did last week, protesting legislative inaction and demanding justice for people living on the front lines of the crisis.

9. Occupy the offices: Sit-ins and occupations of public officials offices are one way to take the protest to the politicians. Campaigners occupied US Senator Pelosi’s office and launched their global hunger strike just before US Thanksgiving weekend. In Oregon, 21 people were arrested while occupying the governor’s office to get her to oppose a fracked gas export terminal at Jordan Cove.

10. Organize a coal train blockade like climate activists in Ayers, Massachusetts. They made a series of multi-wave coal train blockades, one group of protesters taking up the blockade as the first group was arrested. Or rally thousands like the Germans did when they gathered between 1,000-4,000 green activists, made their way past police lines, and blocked trains at three important coal mines in eastern Germany.

11. Shut down your local fossil fuel power plant. (We’ve all got one.) New Yorkers did this dramatically a few weeks ago, scaling a smokestack and blockading the gates. In New Hampshire, 67 climate activists were arrested outside their coal power plant, calling for it to be shut down.

12. Of course, another option is to literally take back your power like this small German town that took ownership of their grid and went 100 percent renewable.

13. Like Spiderman? You could add some drama to a protest like these two kids (ages 8 and 11) who rappelled down from a bridge with climbing gear and a protest banner during COP25 in Madrid.

14. Ground the private jets. Extinction Rebellion members went for the gold: they blockaded a private jet terminal used by wealthy elites in Geneva.

15. Sail a Sinking House down the river like Extinction Rebellion did along the Thames to show solidarity with all those who have lost their homes to rising seas.

16. Clean it up. Use mops, brooms, and scrub brushes for a “clean up your act” protest like the one Extinction Rebellion used at Barclay’s Bank branches.

17. Blockade pipeline supply shipments like Washington activists did to stall the expansion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline.

18. Catch the eye with a Red Brigade Funeral Procession like this one during the Black Friday climate action protests in Vancouver.

19. Tiny House Blockades: Build a tiny house in the path of the pipelines, like these Indigenous women are doing to thwart the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Canada.

20. Make a racket with a pots-and-pans protest. Cacerolazos – pots and pans banging protests – erupted in 12 Latin American countries last week. The media focused on government corruption and economic justice as the cause, but in many nations, including Chile and Bolivia, climate and environmental justice are included in the protesters demands.

21. Share this article. Action inspires more action. Hearing these examples – and the successes – gives us the strength to rise to the challenges we face. You can help stop the climate crisis by sharing these stories with others. (You can also connect to 30-50+ stories of nonviolence in action by signing up for Nonviolence News’ free weekly enewsletter.)

Plus! Here’s a bonus idea from friends at World Beyond War: Connect peace and climate, militarism and environmental destruction, by pressuring your local government to divest from both weapons and fossil fuels, like Charlottesville, VA, did last year, and Arlington,VA, is working on right now.

Remember: all these stories came from the Nonviolence News articles I’ve collected in just the past 30 days! These stories should give you hope, courage, and ideas for taking action. There’s so much to be done, and so much we can do! Joan Baez said that “action is the antidote to despair”. Don’t despair. Organize.

__________________

Rivera Sun , syndicated by PeaceVoice , has written numerous books, including The Dandelion Insurrection . She is the editor of Nonviolence News and a nationwide trainer in strategy for nonviolent campaigns.

December 2, 2019

The Apology & Forgiveness Song – An Excerpt From Desert Song

Image by Bruno Glätsch from Pixabay. CCO

Image by Bruno Glätsch from Pixabay. CCOAuthor’s Note: This excerpt is an example of the kind of compelling fiction we can write when we integrate the current best practices and experiments in conflict resolution. In the story, the Atta Song (Apology and Forgiveness Song) is part of Harraken culture, a way of admitting wrongs and making them right. This tradition is inspired by many sources, including Truth & Reconciliation Commissions, restorative justice, and several other Indigenous practices of reconciliation.

The Atta Song at the Crossroads

An excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun.

You can get a copy through our Community Publishing Campaign.

Voices twittered like birdsong under the

arching boughs of the orchard. In the shade, rows of stalls and booths

displayed crafters’ goods and artisans’ wares. Between the summer rains and

autumn harvests, smiths and metal shapers, weavers and silk spinners, potters

and stone carvers gathered at the Crossroads to barter and trade. Harraken

journeyed from the distant corners of the desert to place orders and pick up

promised goods. Messengers hawked a lively trade, delivering and returning.

Beyond the green of the trees, the blazing

white of the Deep Sands Valley encircled the Crossroads. The dunes sparkled with

stark beauty. Every year, the prevailing wind shoved the sand’s edges closer to

the eastern flank of the vast orchard. Each year, the crafters’ apprentices

shored up the massive retaining walls that held it back. For centuries, that

had been the honor-bargain between orchardists and crafters: shade and water in

exchange for cooperation in holding back the dunes. The aqueduct that carried

the sluice of water from Turim through the Deep Sands Valley was a marvel of

engineering. It carried and protected the lifeblood of the seasonal city of

fruit and arts.

Along a spider web of footpaths, people

gathered for games and meals, gossip and story. Low stools and spread rugs

formed open air sitting rooms. A sense of repose and ease marked the banter, negotiations

halted for songs. At night, laughter rose with a festive spirit.

Today, however, a buzz

of rumors swarmed the market like the hives of bees that lined the orchard

edges. A plume of dust rose along the northwest section of the Market Road.

People claimed that an army of women approached, not the Black Ravens, but the

unarmed women who rode from village to village reinitiating the village sings. Three

days ago, the Harrak-Mettahl had ridden in and slept curled up in his cloak under

the trees. Over breakfast, he’d told the potter next to him that he envied the

strength of the potter’s wares. Harrak, he had said, was easier to lose or

break . . . and harder to repair.

“Whose harrak are

you restoring today?” she’d asked him amiably.

“All of ours . . .

starting with my own,” he’d replied, looking so mournful that wild

whispers of gossip speculated that he must have murdered someone.

All through the first

day, Tahkan Shirar went from one person to the next, asking their views on

warriors-rule versus village sings. The artisans tended to support the sings.

They weren’t warriors, after all, and what did warriors know of their trades? Last

year, the warriors had levied a goods-tax on the Crossroads to support the fighters.

The artisans resented it bitterly. In times of peace, why should they pay for

warriors who rode around eating food and swinging swords and doing nothing?

On the second day, he

gathered them together and made a request that sparked roars of outrage and indignation.

It took the Harrak-Mettahl hours to explain what he meant, why it mattered,

what he’d learned from the women who rode with his sister toward the

Crossroads, and why the artisans should honor his unusual request. He talked

long into the evening, persuading and cajoling. At last, he struck a bargain, a

daring wager to which they all agreed.

By morning, the buzz of

tension, gossip, and excitement reached a fevered pitch. One by one, the

haggling fell off. The hammering of horseshoes halted. People wandered toward

the westbound Market Road to watch the growing plume of riders’ dust.

Would

he really do it, they wondered?

Bets were placed. Nails

were bitten to the quick. Toes tapped nervously. When the company of riders

reached the edge of the Crossroads, Tahkan Shirar walked out to meet them.

Hundreds of crafters and artisans followed in his footsteps, curiosity burning

like a fever in them.

He stood beyond the

overhang of fruit trees, sleeves rolled to elbows, skin dark with summer sun.

He looked thin, his usual wolf-leanness whittled down. A quietness clung to

him, the stillness that comes from deep reflection. His face curved with

smile-creases as he saw the riders. Ari Ara jumped down from Zyrh’s back

at a run, greeting him after the week of travel. Just as she threw her arms

around him, she caught a glimpse of his sorrow darting behind his smile.

“What is it?”

she asked.

“Nothing to worry

about,” he said, gently touching her cheek. He had missed her this week.

It seemed she had grown taller since they last parted, and the speed of passing

time struck him strongly. He’d lost her for most of her life and mourned every

moment they had to spend apart.

As Mahteni dismounted

and walked across the open space between riders and waiting crafters, swirls of

dust chased her heels like tiny dogs. Tahkan stepped out to meet her. The first

words of his song struck the space between them and she paused. Her face fell

open like a book. Surprise and shock wrote volumes across the pages of her

features. The Harrak-Mettahl was singing the Atta Song, the ritual chant of

apology and forgiveness. He held out his hands in supplication, palms up. He

dropped to one knee, then two, then sat back on his heels with his palms on his

thighs and his head bent.

I am sorry, he sang,

for all the wrongs done,

for every slight and every silencing,

for every bruise and tear,

for the honor lost by men and warriors,

for all my faults and failures.

The Harrak-Mettahl had

a responsibility to uphold the honor of his people. If they lost their way, he

had failed his duties. Tahkan Shirar offered his apologies for his part in the

problems and for the ways his actions had made the situation worse. It was

wrong to silence anyone, he sang.

We are born equally of our mothers,

our feet rest equally on the sands,

the Ancestor Wind flows equally

through each person’s song,

the rain bestows its blessing,

equally upon all our heads.

Ari Ara sensed the

crafters behind him tightening like a bowstring, as if the outcome of this

moment decided their fates and futures. From the look of shock on their faces, Ari Ara

guessed that the Harrak-Mettahl didn’t often get down on his knees. She had

once seen her father gather power like lightning to his chest and stride into a

hall full of enemies like a tiger showering white sparks. He pulled that same

power to him now; she felt it crackling in the air. His words sang of what it

meant to be a man, a Harraken man. The Ancestor Wind stirred above them,

bringing a sense of time and culture, antiquity and ancestors, to the ritual.

Gestures of greeting fluttered from one Harraken to the next as the Ancestor

Wind spiraled into a whirlwind, reaching down between the Shirar siblings,

whipping their clothes and hair with its spinning winds.

If it is time for you, Tahkan sang to Mahteni-Mirrin,

to be our harrak-mettahl,

I release the wind to you.

The gasps of the

Harraken made the wind spout waver, swaying on their in-drawn breaths.

Forgive

me? Tahkan

asked his sister.

Mahteni bent her head

as if listening to the hushed whispers of the swirling wind that Tahkan held

out like a flower on the palm of his hand. Ari Ara made herself breathe

mechanically, frozen as the rest as her heart galloped madly in her chest.

At last, Mahteni spoke.

“Keep the Ancestor

Wind, brother. We need you to call the spirits of the ancient grandfathers to speak

to their grandsons and descendants.”

She made a small

gesture. The wind spout dropped to touch the earth at their feet, stirring the

dust. Everyone flinched and covered their eyes, waving the plumes away as they

coughed. When the dust cleared, Mahteni clasped her brother’s hands and lifted

him to his feet, the reply of the Forgiveness Song on her lips.

Ari Ara joined in

with the rest of the women, moved to tears. In the second refrain, she heard

the men’s voices joining from among the crafters. She thought she’d never heard

anything so beautiful as the full spectrum of voices, low and high, honoring

their honor keeper as his sister lifted him to his feet. When he rose, the

heads of his people rose with him and the weight of shame and anger lifted from

their backs. Tahkan Shirar, thin from fasting, trembling with power, stood both

humble and proud, a man of his desert culture, a keeper of honor once more.

Ari Ara couldn’t

keep it back: the Honor Cry broke loose from her throat, high as a piercing

hawk’s scream, sharp and clear. It unlocked the throats of others and like a

storm, the sound charged into the air. Tahkan’s eyes shot to his daughter, and

he nodded his thanks to her. When the cry quieted, Tahkan turned to the

crafters still hidden in the shade of the trees.

“My part of the

bargain has been met,” he announced. “Now you must honor your end of

our deal.”

With that, Tahkan

gestured and the crafters filed out from under the trees. The astonished women

parted to let them pass, out of the market and into the dust of the road.

“There are as many

Atta Songs to sing as there are people,” he told Mahteni, “and we

hope you will do us the kindness of hearing them. The Crossroads is yours. Each

person must reconcile before entering again.”

Ari Ara watched

the crafters step out into the road with resigned and determined looks. It was

as if they had placed and lost a wager. Only later, when the moon rose high

across the sky and the fire embers burned low, did she hear the whole story

from her father.

“I did make a

wager with them,” he told her, practically translucent with the energy of

the day’s events shimmering in his exhausted body. “I wagered everything I

had: my honor, integrity, dignity, even my position as harrak-mettahl.”

“On what?” Ari Ara

asked breathlessly.

Tahkan smiled wearily.

“I told them that

if we offered these women a sincere apology for ignoring this situation too

long, that if we apologized deeply and truly, and committed to being part of

the solution, the women would forgive us.”

When he said the word, atta – to forgive – it shivered in the

air. Ari Ara sensed meanings beyond her Marianan translation. The

Harrak-Tala word for forgiveness had no sense of forgetting to it, no returning

to what was before, no action-less remorse. The Harrak-Tala word was

inseparable from change, from doing differently, from repairing harm. It

reverberated with the willingness to be a different person and to live a different

way. And because it was Desert Speech, the word for forgiveness bound the giver

and receiver like an oath.

“They were afraid

– or resistant – to try,” Tahkan confided, “so, I told them I would

go first. It is my duty as Harrak-Mettahl, after all, to go first where others

fear to walk . . . even into the Atta Song, which frightens men more

than charging into battle.”

If he was forgiven, he

wagered, all of the crafters had to leave the Crossroads marketplace, giving it

over to the women, and enter only after singing the Atta Song.

“But what if you

were not forgiven?” Ari Ara asked in awestruck horror at the stakes.

Tahkan shrugged, a wry

smile on his face.

“Then I would not

be fit to lead my people, anyway, and Mahteni would be a better harrak-mettahl

for these times.”

Tahkan had spent days

listening to the Ancestor Wind, fasting, thinking. The women had just

grievances. In the desert, everyone held up the Harraken Song. Everyone earned

praise when things went right; everyone shared blame when things went wrong. If

two brothers quarreled, the whole village took responsibility for their part in

the argument. If a disagreement came to blows, everyone acknowledged how they

either aggravated the dispute, or did nothing to try to help find a resolution.

If they had turned one brother against the other, they admitted it. If they had

ignored a chance to help the brothers reconcile, they acknowledged it. It was

not just the person who flung a punch who was at fault for an injury, but those

who cheered on a fight, or did not reach out to stop it.

Because of this, the

Harrak-Mettahl needed to find a path forward that restored the harrak of all

his people. No blood debts or honor challenges could solve this dispute. No act

of violence could heal this rift. So, Tahkan sat and listened for a long time, staring

out into the shimmering horizon. At last, the answer had come. In a flash of a

memory, he saw his daughter practicing the Way Between. An old song about

Alaren leapt to mind, reminding him of the root of the word, atta.

“Atta,”

Tahkan told Ari Ara, “is the word for reconciliation. It is not a Harraken

word. It is a Fanten word from times long forgotten. Alaren brought it to our

people in the days of healing from the pain of the first war.”

Atta meant apology,

forgiveness, and reconciliation. It was the same word backwards and forwards.

The Atta Song was a call-and-response, a question seeking an answer, a cry

awaiting its echo. So, the answer to Tahkan’s question was the very question he

had posed: atta for his people, starting with the man who must lead where

others feared to go.

The Atta Song at the

Crossroads went on for days. Tahkan had shown that anyone could sing it; that

everyone played a role in letting the injustice fester, and everyone could help

resolve it. Some had more to apologize for than others. A few sang the song but

were not forgiven on their first try. These people – men and women both – had

ignored complaints from relatives or supported the unjust decisions of

warriors. Tahkan sat with them outside the gate and spoke with them. Mahteni

sat with the women inside the market and talked with them. The Atta Song rose

again, and sometimes a third time, until the people’s willingness to change

rang honest and clear in the notes.

There were some who

refused to sing and rode off to other places. There were many who felt they had

done no wrong. To them, Tahkan was firm and clear: if the Harrak-Mettahl could get

down on his knees and sing Atta for his people, so could they.

“It will build

your harrak,” he pointed out, and no one could deny that Tahkan Shirar had

shown great courage, walked through the fire of the Atta Song, and emerged

stronger than ever before.

The season turned swiftly toward autumn. A touch of coolness hung on the night air. Soon, the Harraken would gather to bring in the crops. When all were reconciled at the Crossroads, the Harrak-Mettahl rode out again, this time toward Turim City to make the same request of those who dwelled within those walls. It was time to apologize, forgive, and change.

__________________

This is an excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun. You can get a copy through our Community Publishing Campaign.

Throw-the-Bones – An Excerpt from Desert Song

Image by Jody Davis from Pixabay CCO

Image by Jody Davis from Pixabay CCOThis is an excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun. You can get a copy by supporting the Community Publishing Campaign.

Up a long, winding ravine, tucked into a pocket meadow, lived a seer named Throw-the-Bones. Her home – if you could call it that – was a hide-covered lean-to half dug into the earth. A sod roof of desert grass grew above it; a rangy, horned goat bleated at them from on top. A desert chicken scratched in the dirt out front, scraggly-feathered with a flopping ochre comb. A dry bone-and-branch fence ringed the hut, white and stark, bleached by the blazing blue sky. Tala nudged Zyrh through the listing gate then slid off to push it shut.

“Leave it

open,” a voice croaked out, dry as a spiny toad.

A hunched figure

staggered toward them. Dangling locks of hair masked her face. Her grotesque

cloak of rodent skulls, crows’ beaks, birds’ feet, and shed snakeskins lurched

with every step.

“You’ll be leaving

quicker than you came,” the woman rasped. “They all do.”

“Not Tala,

Throw-the-Bones, you know that,” Tala called out soothingly.

“What’s

that?” the figure cried with surprise, pushing back her matted hair and

shading the sun from her eyes. “Tala? Well, that changes things. Come in

for tea!”

Ari Ara blinked as

the bedraggled figure dropped the rasping voice and tossed off a tangled wig.

The slender, middle-aged woman cast aside the cloak with a look of disgust. She

patted the stray wisps of brown hair back into place and straightened her

spine. She wore a clean tunic and a bright blue belt. The wrinkles around her

eyes creased at Ari Ara’s astonished expression and she burst out laughing

merrily.

“The ole

cloak-and-croak act is just to scare away unwanted visitors,” she said,

“but a friend of Tala’s is a friend of mine.”

She winked and squeezed

Tala around the shoulders. Ari Ara dismounted and followed the other two

toward the hut. The woman turned with a brisk, no-nonsense attitude and eyed Ari Ara.

“You must know I’m

Throw-the-Bones, but who are you? Potential Tala-Rasa?”

Ari Ara shook her

head.

“Ari Ara

Shirar en Marin.”

Throw-the-Bones’ mouth

dropped open. Her eyes rolled back in her sockets. A tremor shuddered through

her. Tala calmly pinched the woman’s nose, held her mouth shut, and counted to

thirty. At thirty-three and a half, Throw-the-Bones threw Tala off, gasping.

“Thanks,”

Throw-the-Bones coughed out. “Ack. That was a strong one. Good thing she

didn’t come on her own.”

Tala let the wheezing

seer lean on zirs shoulders and lurch into the shade of the hut.

Throw-the-Bones settled in a chair as the young songholder gathered a trio of

small cups along with a little clay teapot. The youth opened the lid and

sniffed cautiously.

“Just a bit of

spring mint,” Throw-the-Bones told the youth. “Nothing to worry

about.”

She threw back her

first cup and gestured impatiently for another while Ari Ara stood frozen

in the doorway with an appalled look on her face, wondering what had just

happened.

“Visions,

love,” Throw-the-Bones explained, pointing to a three-legged stool and

gesturing for the girl to sit. “Such a bother, really.”

“Wh-what would

have happened if Tala hadn’t held your nose?” Ari Ara asked, tentatively

sitting down.

Throw-the-Bones

shrugged.

“Maybe I’d wake on

my own a few hours later . . . or not.”

She shivered despite

the red flush on her skin and sweat beads on her brow.

“Given the

strength of these visions, I might never have come out of them, though old

Stew’s trained to peck me back to life if I don’t feed him his grain on

time.”

She pointed to the

chicken, which stretched his neck and crowed before strutting out of sight.

When Ari Ara turned back, Throw-the-Bones’ sharp eyes were fixed on her

face.

“What did you

see?” Ari Ara asked, clutching the edge of the stool and steeling

herself. There was already one prophecy about her and it wasn’t pleasant. To

her surprise, the middle-aged woman simply rolled her eyes and shoved her cup

across the rough surface of her table for more mint tea.

“Oh no, it doesn’t

work like that. Not even for you, though I’m sorely tempted to make an

exception.” Throw-the-Bones leveled a stern look at Ari Ara.

“No, no, if I risk death to see your future, you’ve got to pay prettily

for that knowledge.”

“But I didn’t ask

you to see my future!” Ari Ara objected.

“Precisely. Which

is why I don’t charge for seeing, only for telling. I’ll be keeping my vision

in my silence until you’re ready to pay.”

“You won’t tell

anyone else?”

“Certainly

not!” Throw-the-Bones retorted, looking insulted. “That’s unethical.

Didn’t you explain?”

The last was directed

accusatorily at Tala, who simply shrugged. The woman blew an exasperated sigh

and turned back to Ari Ara.

“The bone fence,

the skull cape, the raspy voice; that’s all for show. Idiots come to me to find

their true loves or destinies. Most of them have lives so dull it pains me to

wade through the visions.”

She rubbed her temples.

People lived. They tended goats. They met a girl. They married a boy. Children

were born.

“Everyone

dies,” Throw-the-Bones sighed, “and I always see that. It’s where I

get most of my knowledge, though no one likes to hear that. I peek in at the

funerals, count the wedding rings and scars, notice how many children have

gathered, and look for any telltale callouses on people’s hands. That’s enough

to hint at a life . . . though occasionally, I see more. Wars and

famines. Bold lives and cowardly deaths. Simple existences and perfect

happiness. Long-living elders and easy exits. Short flickers and sudden

snuffing outs.”

Throw-the-Bones’ face

grew shadowed. Her fingers clutched the clay cup hard enough to turn her

knuckles white.

“I can see why you

wouldn’t want too much company,” Ari Ara said gently. “I’m sorry

if hearing my name caused you distress.”

The brown-haired woman

looked up. Her eyebrows lifted.

“In all my

years,” she murmured, “no one has ever said that.”

She held out her hand

and squeezed Ari Ara’s palm in gratitude.

“When the day

comes that you face a crossroad of no clear choices, come to me, and I will

tell you which way you went.”

“You could tell

her now,” Tala pointed out, “and spare her the trip.”

Throw-the-Bones

snatched the teapot away and sloshed some more in her cup.

“You are both too

young to know the wisdom of anything,” she grumbled. “Especially you,

cheeky Tala. Such impertinence! Do I tell you how to sing the old songs? No.

You do your job and trust me to do mine.”

Tala looked

sufficiently chastened . . . at least until the youth tossed Ari Ara

a hidden wink behind the seer’s back.

“But none of this

is the question you came to ask, is it?” Throw-the-Bones asked suddenly

with a sharp astuteness, looking from one to the other.

“I need to find my

friend Emir Miresh,” Ari Ara explained.

“The Marianan

warrior?” Throw-the-Bones asked in surprise.

Ari Ara nodded and

related the tale of how she lost him.

The woman listened with

a troubled expression. She tapped her fingers on the wooden table in agitation.

She grimaced.

“Oh, I hate

this,” she groaned to Tala. “Take the cups and fetch the bones.”

Tala cleaned everything

off the battered table. Ari Ara stared at the surface . . . the

blackened gouges looked like a map . . . ah! She tilted her head; it

was the desert. There were the mountains, the foothills, the winding streams

and rivers. Thin red lines wove in intricate patterns through it all,

perplexing her. She reached out to touch the web. Throw-the-Bones slapped her

hand away.

“Don’t meddle. I’m

going to find your friend’s bones, living or dead.”

Ari Ara blanched.

Tala returned with a

basket of old bones, large and small, some shiningly clean, others with bits of

gristle still attached. Throw-the-Bones began to ask her a series of questions

about Emir.

“Short or

tall?”

“Tall.”

She picked out the tiny

fish and bird bones and discarded them to the side.

“Old or

young?”

“Young,” Ari Ara

answered, watching the woman’s hands fly as she tossed out the cracked and

yellowed old bones.

“Color of

eyes?”

“Uh, blue, I

think,” Ari Ara stammered. She hadn’t really thought about it.

“Hmm, not clear

enough,” the seer answered. “Stout or slender?”

“Slender.”

“Water or

fire?”

“Water. He’s like

a river when he moves.”

Each time she answered,

Throw-the-Bones sorted out more bones until the choice was down to two. She

weighed them in her palms, thinking, then set aside one.

“Here, hold

this,” the older woman ordered, tossing the other vertebra to Ari Ara.

“Ew!” she

screeched, dropping it with a disgusted grimace. There were still red tendons

attached to it.

Throw-the-Bones eyed

her, shook her head, and picked the bone up.

“Hmm, how about

this, then?” the woman asked, turning suddenly and snatching something off

the high shelf behind her.

It was a strange stone,

smooth with time and a river’s touch, black as ink, and warm against Ari Ara’s

palm.

“What is it?”

Ari Ara asked, holding it up to the light.

“An old thing from

long ago,” Throw-the-Bones answered. “A tree’s heart turned to stone

by lightning. A bone that is not a bone.”

She stretched out her

hand. Ari Ara gave it back. Throw-the-Bones nodded approvingly as she rolled

back her sleeves and weighed the lightning stone in her palm.

“Your friend has a

very old soul and a truly good heart. If we find him, don’t lose him

again,” the seer advised her. “You do not find friends like him every

day.”

Ari Ara nodded

silently, suddenly hot with embarrassment over the way she’d treated Emir. Throw-the-Bones

began to chant in a low voice, cupping her hands around the lightning stone.

She shook her hands, slowly at first, then rhythmically, chanting faster and

faster until she opened her palms above the table. Her eyes traced the arc of

the fall to where the stone landed squarely with a single thump, no bounce, no

spin.

“This is Moragh’s

Stronghold,” Throw-the-Bones stated, pointing to a black mark slightly

east of the stone. “You last saw Emir here, just to the northwest.”

Ari Ara nodded.

Throw-the-Bones picked up the lightning stone. She repeated the chanting and

shaking, though the words changed slightly. A crackle of energy snapped through

the hut. Her hands split open. The stone fell. It hit the mark northwest of the

Stronghold then spun and spun and spun along the red lines, wavering from one

side of the table to the other, traveling the length from north to south.

Finally, it came to rest in the Middle Pass of the Border Mountains.

Throw-the-Bones scowled

and harrumphed in surprise. Ari Ara opened her mouth to ask, but the woman

lifted her hand for silence.

“Tala, sing the Truth-Telling

Song.”

“But – “

“Do it!”

All the hairs on Ari Ara’s

arms rose up as the two voices joined, one singing, one chanting. The air

tightened as if bound by an invisible noose. Throw-the-Bones shook the stone

between her palms. Her whole body rattled with the gesture, quicker and

quicker. Then, the woman’s hands flew open. The lightning stone hit the table

and spun in place for a long moment. It fell at the exact same spot as before

in the middle of the Border Mountains.

Tala squinted at the

table. Throw-the-Bones scowled and folded her arms over her chest.

“That,” she

stated flatly, “was not what I was expecting.”

Ari Ara couldn’t

stay silent any longer.

“What? What does

it mean?” she blurted out.

Throw-the-Bones’

fingers stretched out.

“There is where you left him.” She

pointed to the first spot then moved, tracing the wandering pathway of the

second toss. “This is where he has been . . . or will be,”

she said. “It’s never exactly clear.”

“So, he’s alive!” Ari Ara

cried in relief.

“Maybe,” the

woman answered with a scowl. “Maybe not. A spinning bone indicates that

someone is on the edge of life and death, spirit and mortal life. I have never

seen a bone dance the threshold line as long as that. It is strange.”

Throw-the-Bones tapped

her chin.

“The third toss is

where you will meet again. Here in the Border Mountains. But your friend still

spun the spirit-mortal dance. Why would anyone move him over all that distance

if he were sick or injured or near death? That, I cannot understand.”

She had thought the

bones hid the truth on the second toss; that’s why she had Tala sing the Truth-Telling

Song. The melody made the bones fall honestly.

“Whatever that

was, it’s speaking the truth.”

“When should I

meet him there?” Ari Ara asked, pointing to the mountains.

Throw-the-Bones looked

up, eyes clouded and distant.

“Do not seek him.

Your paths will find each other.”

Then she shivered out

of her reverie, stoked the fire, and refilled the teapot. She bustled about the

hut, ignoring Ari Ara’s pestering questions, packing away the bones,

replacing the odds-and-ends on the table, tossing a handful of grain to Stew

the Chicken. Tala quietly rose and gestured to Ari Ara to follow; they’d

get no more out of Throw-the-Bones.

“Wait.”

The woman’s voice

stopped them as they left. She snatched the lightning stone off the table.

“Take this.”

“I couldn’t,”

Ari Ara protested.

Throw-the-Bones shook

her head.

“It is tied to him

now. I can’t use it again.”

She grabbed Ari Ara’s

wrist, turned her hand over, and placed the black stone in the girl’s palm.

“There is the

matter of payment, too,” Throw-the-Bones said sternly.

“I have little –

” Ari Ara began.

The woman held a finger

up to her lips and tilted her head as if listening . . . or

remembering.

“You will travel

the dragon ranges, the desert ridges, the marshlands, the desert sands,”

she chanted in an odd, distant tone. “Your paths will crisscross past the

Crossroads, but your eyes will not meet until after the women and warriors

collide, and the exile is exiled from exile.”

Throw-the-Bones’ eyes

rolled back in her head. She shivered. The woman’s limbs shook from head to

toe. She gasped as if she was resurfacing from a deep dive into a cold lake.

She braced her trembling palms on the table.

“For

payment,” she croaked, “you will promise me something.”

“What?” Ari Ara

asked warily.

“When the young

warrior returns, the old warrior will ask for your help. You will give

it,” Throw-the-Bones stated firmly.

A shiver and tingle ran

through Ari Ara’s spine. She nodded.

“No more questions now,” the seer insisted. “I have no more answers for you.” She hustled them out the door, onto Zyrh, and beyond her gate. As the latch clicked into place, she eyed the redheaded girl riding away. She had no more answers for Ari Ara Shirar en Marin, not until they next met on the long road called life.

____________________

This is an excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun. You can get a copy by supporting the Community Publishing Campaign.

November 22, 2019

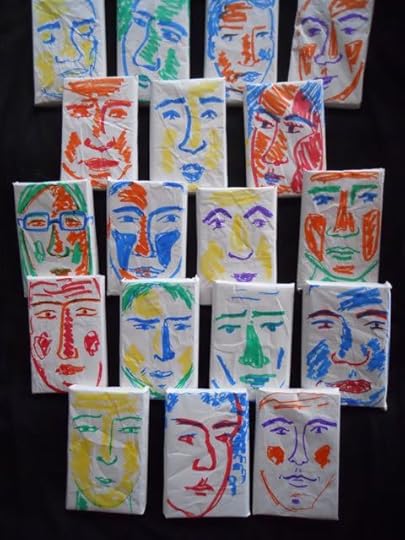

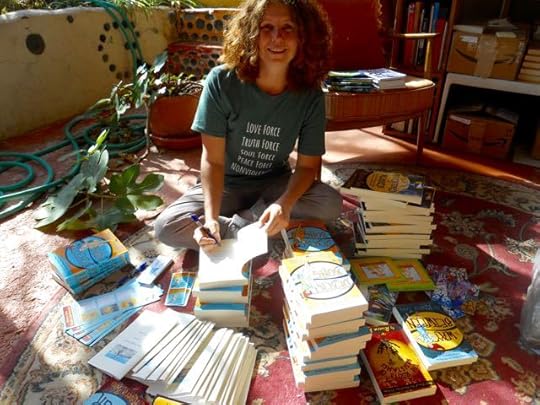

Blind Date w/ a Book; Take Home an Adventure! Get a FREE Rivera Sun novel.

Note: The Blind Date w/ a Book Sale is limited to the United States.

We like to have fun around here. Hence our “Blind Date with a Book” sale. This weekend, Thurs-Mon (Nov 21-24), for every book you buy on my website or publishing campaign, I’ll send you a FREE surprise “Blind Date Book”. Wrapped in hand-drawn paper, each book is one of my novels – but you won’t know which until you open it! And yes, these make really fun holiday gifts. Stick them in your local Little Free Libraries, throw them into the office gift swap, put them under the tree … whatever you do, enjoy them!

The Blind Date with a Book Sale lasts Thurs-Monday only. Every person who buys a book from my website OR through the Community Publishing Campaign for my newest releases will get a free “Blind Date Book”.

Blind Date Book titles include:

The Dandelion Insurrection

The Roots of Resistance

The Way Between

The Lost Heir

Billionaire Buddha

Steam Drills

Hiding under these Blind Date Book hand-drawn covers are limited editions, slightly off-kilter prints, and original edition book covers. All of which you can auction on ebay when I’m someday as famous as J.K. Rowling. (I’m working on that part, with a little help from all of you.)

It’s a wild adventure, being a Community-Supported Writer. It’s an adventure I wouldn’t trade for the world. Thank you all for being a part of it. What other publishing operation offers a Blind Date with a Book?

With laughter and a sense of mischief,

Rivera

November 21, 2019

It’s time. End the draft, once and for all.

Image from SnapwireSnaps on Pixaby

Image from SnapwireSnaps on PixabyWe may be months away from ending the US military draft, once and for all. After a court ruled that the male-only draft was unconstitutional, a Congress-appointed Commission has been studying whether or not to draft women into the US military. They make their report in March, and will likely either advocate for expanding draft registration to women or abolishing the draft, once and for all.

Instead of expanding the draft to women, it’s time to end the draft for all genders.

Drafting women is a deeply unpopular idea. For months, people have been testifying against it to the Commission. Even the former director of the Selective Service thinks it’s time to get rid of draft registration altogether. Currently, the US military draft is in a state of dysfunction. For decades, millions of men have refused and/or failed to register. The consequences can and do impact men’s lives, including everything from being barred from government jobs to being denied drivers licenses. This situation is deeply unjust and has been opposed for decades by several generations of draft resisters.

Expanding the draft to women will only deepen its unpopularity and make it even less functional as women join the ranks of draft resisters.

Some people, particularly men, say that if women want equal rights, they should be equally drafted. Feminists of all genders reject this idea. There’s nothing feminist about drafting women. While we support equal access to opportunity and employment in all sectors of the economy, gender equality cannot be achieved by forcing women against their will into the military. Involuntary conscription – for anyone – is an affront to liberty. No one should be forced into servitude against their will. There are words for that, slavery and exploitation among them.

The only moral form of equality is to end the draft for all genders.

Women, specifically anti-war feminists, have opposed the draft for centuries. They have robustly critiqued war and militarism, and continue to do so to this day. In solidarity with women around the world, they refuse to support wars and decry the specific ways that war disproportionately harms women civilians and their children. True gender equality does not mean forcing women to fight wars they oppose. It means including women’s voices – in balance with people of all genders – at all levels of policy making. It means waging peace, not war. It means incorporating the practical and effective tools of peacebuilding, diplomacy, unarmed peacekeeping, civilian-based defense, civil resistance, and more into our approaches to conflict.

We stand at a crossroads. This is a moment where the United States could take a step forward in ending a policy that is deeply disliked and resisted by millions of men. The military draft is unenforceable, unpopular, unsupported, unequal, and unjust. It’s time to call for the end of the military draft. The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service is soliciting comments on all forms of national service. They need to hear from people urging them to end the draft and draft registration for all genders. Make your comments to the Commission until December 31, 2019.

Here are the three main points many people are making:

1) Draft registration should be ended for everyone, not extended to women;

2) All criminal, civil, federal and state penalties for failure to register must be ended and overturned for those currently living under these penalties; and

3) National service should remain voluntary. Compulsory service, whether civilian or military, is in conflict with the principles of a democratic and free society.

Speak up. Raise your voice. This is an important moment, one that might prove to be a breakthrough moment if we speak decisively and urgently. Tell the Commission: it’s time to end the draft for all genders, once and for all.

__________________

Rivera Sun , syndicated by PeaceVoice , has written numerous books, including The Dandelion Insurrection . She is the editor of Nonviolence News and a nationwide trainer in strategy for nonviolent campaigns.

November 18, 2019

What Song Will You Sing?

This is an excerpt from Desert Song: A Girl in Exile, A Trickster Horse, and the Women Rising Up. You can get this new novel through our Community Publishing Campaign here.

When the first touch of lengthening shadow broke the afternoon heat, Ari Ara forced herself through a set of training exercises in the Way Between. She missed Emir and Shulen so strongly that the world blurred, but she blinked her tears back and kept going. She couldn’t risk losing her edge; her encounter with Moragh had demonstrated that. She finished the exercise and paused to catch her breath. She reached for the waterskin and noticed Tala watching her with a blend of awe, mystification, and wistful yearning.

“The exercise

makes more sense with two people,” Ari Ara explained, “but you

can practice with the wind or the sunlight or anything, really.”

“Could I

learn?” Tala asked, eyes alight with curiosity.

“Oh, yes!” Ari Ara

cried, thrilled that the youth had asked.

Thus began a routine

that shaped their days: rise before dawn, ride to the next water source, rest

through the midday heat, practice the Way Between, and travel at dusk for a few

hours. They crossed a crumbling salt flat of blinding white dust. They tread

through an eerie dead forest of charred and burned branches. They climbed

winding switchback paths over an obsidian ridge of shining black stone. The

desert unfolded, step by step, strange and magnificent, no two places alike.

Ari Ara had always imagined her father’s land as flat and dry, but the

reality filled her with wonder. She had thought there would be no water, but,

in truth, water shaped the culture of the desert, sparse and sacred. Villages

clustered along the handful of rivers – streams, really – that snaked through

the land. She enjoyed traveling with Tala, who knew hundreds of tales. The days

flew by swiftly. The young songholder was fascinated by the riverlands and

plied Ari Ara with questions. The Fanten intrigued Tala, who referred to

the elusive forest-dwelling people as distant cousins of the Tala-Rasa . . .

at least, that’s what Ari Ara thought the Harrak-Tala words meant. Her

vocabulary was growing daily, but Tala’s speech was the most poetic and complex

she’d encountered. It was a mark of the Tala-Rasa’s calling, her friend

explained.

“We never forget a

word, and we keep them alive for others,” Tala explained, building a

small, grass-fed fire to cook a powdered stew for dinner.

“Has it always

been like this?” Ari Ara asked, flopping onto the grass with relief,

splaying her limbs into the soft greenness of the pasturelands. Tomorrow, they

would reach Tuloon. “With the warriors meets cancelling the village sings

and making all the decisions? And is it like this everywhere in the

desert?”

“No, and no,”

Tala answered, voice rough with bitterness. “The War of Retribution

changed everything. I will sing the ballad for you.”

Tala’s clear voice rang

out like a reed pipe, high and bright. The youth’s range was startling, soaring

high like silver bells and bird’s whistles, then dropping low as a man’s all

the way down to the rumble of shaking mountains. The words Tala evoked shivered

with time and history. It was believed that when the Tala-Rasa sang, the

ancestors spoke through them.

From the time beyond

memory, men and women had always been equals in Harraken culture. This was the

world that Ari Ara’s mother, Queen Alinore, had encountered when she first

visited. This was the way of life upon which the peacebuilding young queen had

forged the basis of trust between the two populaces of long-time enemies. Queen

Alinore’s marriage to Tahkan Shirar opened a golden era of exchange and peace.

Trade flourished. Youth programs initiated host exchanges and built friendships

across borders. Tala’s song illuminated the hope of these times, almost

unfathomable to those born during or after the bitter War of Retribution. The clouds

of darkness closed in from both sides of the border. Shadows cast by fear,

hatred, and violence dashed the hopes of a generation.

The Harraken swore they

were not like the riverlands people.

Fathers forbade daughters from acting like the “uncouth Alinore, so forward

and manipulative”. Husbands told wives to stay home with the children –

unlike Alinore’s monstrous cousin Brinelle who left her young son at home to

ride into battle against them.

But it was more than

hatred of the Marianans that fueled the current tensions. As the war dragged

on, the strong men were called to fight. The women were sent to hide and flee

with the children. The warriors meets made emergency decisions, quick choices

to save lives and protect their people.

“It was necessary

for survival, but the balance of our culture was tipped,” Tala added on a

worried note. “The warriors did not let go of power after the war ended.

Not all the village sings were started again. Because most warriors were men,

the women’s voices were slowly silenced.”

The power of Desert

Speech brought the scenes to life as Tala sang the story in a long ballad.

Swirling in the smoke of their grass-fed fire, Ari Ara saw visions of the

vicious cycle of warriors making choices to support young men’s trainings and war

preparations. She saw people – mostly women – objecting and being silenced and

pushed to the sidelines. She saw the warriors meets growing in strength and

authority as the sullen and resentful glares of women spread from face to face.

She saw women fleeing to Moragh’s Stronghold and women weeping in the dark,

fists to mouths to keep silent sobs from waking those around them. Then,

abruptly, as if waking from a nightmare, the vision halted. Tala’s face came

back into focus. The fire had burned down to embers.

“Why’d you

stop?” Ari Ara asked, a plaintive note creeping into her voice.

“The Tala-Rasa

tell the past, not the future. We are not soothsayers. What comes next is up to

the people.”

Ari Ara’s eyes

narrowed as she caught a faint sense of rote phrases in her friend’s words.

“Is that what you truly

believe? Or is that just what you’re supposed to say?” she challenged,

crossing her arms over her chest.

Tala threw her a

startled and uncomfortable look.

“I have been

warned – repeatedly – to listen and recite, not speak and meddle,” Tala

answered with a grimace. Ze picked up a stick and stoked the coals back to

life, tossing a few twigs in with angry strength. “But, what is a voice if

not to sing? Every story is woven out of many strands of possible stories.

History is not neutral. Many of the thirteen Tala-Rasa would have sung a

different song than I did tonight. If the Tala-Rasa can create new songs out of

the present, why not sing warnings of the future, too?”

The youth’s bright eyes

gleamed across the fire.

“If warriors-rule

or Moragh’s violence are the only answers, what is someone like me to do?

Neither seem like good songs!”

Tala shuddered. Neither

male nor female, what place would ze have in this new culture? Would Tala be

the dominator? Or the dominated?

“Is that why you

came looking for me?” Ari Ara asked. “Seeking the girl who is

neither this nor that?”

Tala nodded vigorously,

a grin spreading wide.

“I came looking

for the daughter of our Harrak-Mettahl, the one who restored our water, honor,

and people, the follower of the Way Between.”

Tala’s laughter rang

out. From the lopsided grin, Ari Ara suspected that her life sounded like

a legend to most people. Suddenly, her father’s words came back to her from a

letter he had written her last year.

You

will find, Ari Ara Shirar en Marin, that your legends grow far taller than

you. You will catch up to them in time.

A silence fell. Tala’s

sharp gaze stayed fixed on Ari Ara. The fire danced. A night bird hooted

in the distance. The breeze carried a slip of cooler air across the pastures.

“If you were

allowed to sing a future song,” Ari Ara said quietly, “what

story would it tell?”

A shimmering intensity

burned in the youth’s eyes as if the music pressed suddenly against the

confines of zir chest.

“It would

tell,” Tala began, speaking the story instead of singing it, swallowing

back emotion, “of two youths who did not fit into the world as it was . . .

and so set out to change it, together. It would tell of a girl who knew little

of her father’s culture, but recognized wrong when she saw it. It would sing of

the Way Between, a legend among us, returning like the water and nourishing our

harrak, our honor, until it grew green and strong again.”

Tala’s face flushed,

neck burning red like a boy’s, long eyelashes fluttering like a girl’s, teeth

biting lips like all nervous young ones who reveal their fierce vulnerabilities

like first crushes then wait for disaster or euphoria to strike. Ari Ara said

nothing for a long time, thinking about the words. Tala turned redder and

redder. At last, the youth drew the cloak hood over zes tight crop of black

curls with their iron-ore edges, hiding zirs face.

“Just think it

over and tell me in the morning,” came the muffled comment.

“I don’t need

until morning,” Ari Ara answered, blinking as she realized her friend

was waiting in agony for her reply.

The hooded figure

stilled.

“And?”

So much weighed on that

one word.

Ari Ara smiled and

curled on her side.

“I like the sound

of your song,” she said.

A muted squeal of excitement leapt out of the youth. Ari Ara’s grin gleamed in the darkness. Then the two closed their eyes without speaking further, letting sleep pull their thundering hearts and racing minds into visions and dreams.

______________

This is an excerpt from Desert Song: A Girl in Exile, A Trickster Horse, and the Women Rising Up. You can get this new novel through our Community Publishing Campaign here.

November 17, 2019

9 Reasons To Love The Ari Ara Series

by Leah Cook

You can find the Ari Ara Series, including the two new books, via our Community Publishing Campaign . If you’re new, check out the Whole Series supporter level. Just looking for the first book in the series? Visit my online store.

Let me tell you what’s really cool about this series:

1. It’s written for young adults (the kid characters are ages 11-13 so far), and the kids feel *real* to that age. They don’t magically understand things and they struggle with their emotions and frustrations and they leap and whoop with their excitements. Sometimes they think the solutions are simple, and sometimes they’re right, but not always.

My niece and nephews (ages 8-12 now) *love* these books. Some kids who read the books dressed up as two of the main characters for Halloween, and made their own costumes right down to the details described in the books.

2. It’s about the complex, challenging, important work of finding the ways of peace without violence, and it’s not some flakey version of that that’s all sunshine and roses. The stories of Ari Ara, a shepherd girl, learning about this show both the natural instincts we have to mediate conflict resolution, and the discipline that’s required to be creative if we want to find solutions that will work without falling back into stubborn win-lose dynamics.

It takes ideas like Aikido and Capoeira and finds ways to embody them in the Way Between, which is both a way to fight without trying to inflict harm, and a way to think about how to find peace between people. Some parts of it are easy for Ari Ara, and some she really struggles with. As she learns, we do too.

3. It takes place in lands where pain exists. The histories of the kingdoms include war and distrust, and things done that were wrong on both sides. The people in the stories have experienced searing personal pain, or the loss and pain of being alone on the outskirts of belonging, and these books have a place for that in a young adult’s world.

For children who may not have words for things they have experienced or who may not realize what the adults around them have been hurt by, the characters are shown in their own lives and histories without wounding the reader. It gives place for the existence of real pain and hurt in a story world where it is safely treated and safe for the kid (or adult) to read. You’ll have to read for yourself to understand what I mean, but it’s an important feature of the books (to me). It teaches compassion, both for others and for one’s self.

4. There is an unforgettable scene in the first book, The Way Between, where the most revered Warrior in the Riverlands is seen literally fighting his ghosts. It is searing and agonizing to read, and is a surprising and devastating portrait of PTSD and the legacy of violence that goes beyond an acronym and the news. It shows the toll and the exhausting cost of the battles that this Warrior has to fight privately every day of his life, long after the events that started it.

Again, it is a powerful scene, but will not harm the reader. The character is inspired by one of our own Warriors in the US who helped found Veterans for Peace, opening a nuanced conversation about war and what it does to those who fight it.

5. Ari Ara’s friends are diverse and their own people. They aren’t tag-alongs on the hero’s journey. They’re their own people, with their own desires, impulses, and lives. They’re interesting, from Minli, the crippled monk’s assistant, to Rill, the Urchin Queen in the capital city of Mariana. None of them *need* Ari Ara, let alone need saving by her. They are *friends* to *each other*. That kind of friendship and relationship to each other is a healthy, good thing for kids or us to see.

6. Ari Ara is not good at everything. She doesn’t magically become effortless at everything at any point in the books. She struggles with some things, excels at others, and covers up what she doesn’t know at different times. She hides her weaknesses out of insecurity, and she gets hurt and frustrated with the only adults who expect her to meet her capabilities. Feels true to me, I don’t know about you.

7. They are stories about identity and family–the longing to know who you are, to belong, to be loved, and what a tumultuous thing it is to learn new pieces of your own story and have to adapt what you tell yourself your story is. They are about learning to open your mind and your heart to hear who the people are in your story and what they felt and feel, not just your own pounding heartbeat. They’re also stories about honoring yourself *and* the people you come from, and how that’s not always an easy thing.

8. In these worlds, there are so many ways of giving meaning and words to things. In the second book, a desert woman shares a rite of passage ceremony with Ari Ara when she gets her menses. In the first book, the Fanten grandmothers’ whole lives are tied to a seasonal cycle. The urchins of the capital city make meaning from the scraps of cloth they are ‘paid’ with for their work, and it becomes a way of reclaiming agency and dignity instead of just being indigent. The Mariana city people use coded languages of fashion to send political messages. The desert people must import their words with truth and the *nature of the thing they speak* in order to actually be speaking their language.

These books offer young readers (and older) entirely new modes of meaning and ritual and language. In an increasingly multicultural, non-monotheistic society and country, this introduces something very important for any person. Churches used to (and still do) provide this for their parishioners. These books offer many ways for readers to think about observing important moments in their lives or imparting meaning in what they do.

And lastly, 9. They’re just damn good stories. Magic, real emotions, ups and downs, conflicts and exhilaration, brand new worlds with new cultures to learn, growing up… they’ve got them all. They’re just good reads.

So, if you haven’t checked them out, I highly recommend them! Check ’em out.

___________________

You can find the Ari Ara Series, including the two new books, via our Community Publishing Campaign . If you’re new, check out the Whole Series supporter level. Just looking for the first book in the series? Visit my online store.

Desert Horses

This excerpt is from Desert Song, Rivera Sun’s newest novel. You can get a copy by supporting the Community Publishing Campaign . Thank you!

A stunning view spread before them. The city’s dwellings ended abruptly at a chest-high stone wall. Cliffs plummeted down a hundred feet to a narrow lake fed by the river that cascaded over the precipice in a thunderous waterfall. A strip of green meadow followed the lakeside. Beyond that, a sea of white sand dunes rose and fell to the western horizon. Ari Ara and Emir leaned over the stone wall that ran the length of the cliffs. At the bottom were the horses.

Chestnut, roan, dappled

grey, shining blacks: they dotted the green meadow as far as the eye could see.

Fillies and colts gamboled beside nursing mares. A pair of stallions raced

along the edge of the white sands. Untethered, fenceless, they grazed on the grass

and gathered by the edge of the lake, magnificent, tall, and proud.

“Do all these

horses belong to people in the city?” Ari Ara stammered, awestruck by

the sheer number of animals.

“There is a

centuries-old debate on who belongs to whom: horse or rider?” Tahkan

replied. “I would guess that a third of the horses down below look to

someone in the city. Another third will travel with a human when they feel like

it. The rest would never deign to carry a human about.”

He led them to a hidden

staircase carved into the cliff. The steps zigzagged down a chute, opening onto

railed landings that overlooked the plain. Toward the bottom, narrow balconies

served as viewing platforms during horse races – and defensive balustrades in

times of siege. The staircase ended beside the lake. A line of storage rooms

had been carved into the base of the cliffs to provide space for tack and

grooming tools.

Ari Ara and Emir

stared in awe at the horses. The creatures rose even taller than they had

looked from atop the cliffs. These were not the shaggy ponies, placid and

patient, that Ari Ara had seen the High Mountain villagers using to pull

carts and plow fields. Long-legged and powerful, the desert horses rippled with

strength. They crowded around the humans, curious and massive. The shortest one

stood as high as Tahkan’s shoulder – and he was not a small man. The rest

towered over Ari Ara, bumping their flanks up against her and narrowly

missing her feet with their stamping hooves. The horses’ manes rippled with

hints of fire and wind. Under the familiar grassy aroma, the scent of heat and

dust clung to their hides. Their black eyes reflected the blue of the sky. Mahteni

whistled through her fingers. A mare with a jet black mane and a misty coat shoved

through the pack to reach her, head bobbing in delight.

“Good to see you,

too, old friend,” the desert woman murmured.

Mahteni’s farewells

were brief. She hung her saddlebags over the horse’s back, slung her waterskin

over her shoulders, urged her niece to avoid trouble, and repeated back

Tahkan’s last instructions. He sang a safe journeying song to bless her travels.

Then she sprang to the back of the grey horse with a leap Ari Ara couldn’t

follow. As she rode away, she swiveled and called back to her brother.

“She needs a

horse, you know.”

Tahkan blinked in

surprise.

“I thought it was

too late,” he murmured.

Mahteni’s laugh rang

out.

“It’s

tradition,” she reminded him. Then she waved her arm in one last farewell

and cantered off.

“What tradition?”

Ari Ara asked.

Tahkan’s slow smile

grew.

“Harraken custom

holds that a father chooses his daughter’s first horse. I thought I had missed

my chance, finding you so late in life, but Mahteni thinks you’ve never had a

horse?”

Ari Ara tossed him

a wild-eyed look and gulped, muttering under her breath as she flushed red as

an apple.

“What was

that?” Tahkan asked.

She shook her head and

wouldn’t answer.

Emir leaned close and

murmured an explanation to Tahkan: she’d never

ridden a horse – not once in her entire life. The older man threw an askance

look back at the youth.

Well,

she’ll have to learn, Tahkan thought. The daughter of the

Harrak-Mettahl must be able to ride.

It was a matter of harrak, a point of honor and pride.

He whistled. A tall,

black mare by the river lifted her head. Her ears flicked toward the figures by

the high cliff. She shook her dark mane and paced over.

“She is annoyed at

me for leaving her for so long,” Tahkan chuckled.

Tahkan’s mare sniffed Ari Ara

from foot to head, sneezed twice, and turned her fine-boned head in Tahkan’s

direction with a long-suffering expression.

“Stop that,”

Tahkan chided. “This is my daughter – of course she’s a rival for my

affection. Go find a good friend for her among your four-legged relatives,

would you? And this is Emir Miresh, a great young warrior from the riverlands. If

Tekli is about, tell him I request a favor.”

Ari Ara and Emir raised

their eyebrows over the man’s conversation with the horse . . . but

when the mare trotted away and returned with two other horses in tow, their

mouths fell open.

“She understood

you?” Emir blurted out in disbelief. “What magic is this?”

“Only our

language,” Tahkan answered simply. “Or perhaps her

intelligence.”

He shrugged. It was

difficult to interpret whether a stubborn horse couldn’t or wouldn’t understand your requests. Who

was he to judge? He welcomed a short, piebald horse with a black mane and tail,

and introduced him to Emir.

“You are both from

the riverlands. Tekli will know your Marianan words for stop and go, and

respond to your style of riding. He has run with our horses for years since we

rescued him from Marianan merchants.”

He left Emir and Tekli to

get acquainted and turned to the second horse with a skeptical look. The black

mare had chosen a golden blonde stallion with a distinctive white mane.

“Are you mad?

He’ll kill her,” he objected in a low hiss to his mare.

The mare stared

steadily back at her human, nostrils puffing, lips curling back from her teeth

in what Ari Ara suspected was a horse-laugh. Then the mare quieted and

nudged Tahkan with her forehead.

“You’re

certain?” he asked her, eyeing the golden horse with a father’s worried

disapproval.

Desert children grew up

on horses, riding behind or in front of their parents or older siblings, taking

turns riding solo on the more tolerant horses. When they grew old enough, the

mothers chose their sons’ first horse and the fathers chose their daughters’.

The friendship might last only a season or two, though insightful parents tried

to find horses that would make lasting bonds with their humans. Tradition held

to pairing complementary qualities: a headstrong boy was given a cautious

horse; a shy girl was offered a confident one. The pair learned from one another