Neville Morley's Blog, page 56

September 19, 2016

Life’s Taking You Nowhere?

How should we imagine a world without work, and prepare ourselves and our society for it? The publication of another “the robots are coming!” piece in this morning’s Grauniad brought the passing thought that maybe we could look to classical ideas of the Golden Age, as sketched by Hesiod and others, when the Earth fed its children without any need for them to drag it out of her with violence and endless physical exertion. The idea of such a comparison is not that it will offer us a template for the fully automated leisure society – there are only so many babbling brooks besides which to recline while singing songs to the nymphs, even in temperate regions – so much as a means of deepening the debate by highlighting some assumptions that might otherwise be taken for granted.

For example, as I think I’ve mentioned before, there’s a tendency in those sorts of future-gazing pieces to assume that technology is the thing that’s moving, against a fixed backdrop of universal and eternal capitalism. To be fair to Avent, the possibility of an alternative is recognised in passing, though framed in terms of “social collapse” if it proves impossible to accommodate the new population of the permanently unemployed within the existing system; the article is focused on the medium-term problem of reconciling the self-satisfied winners within global society to the idea that their taxes should support a basic income for everyone else. Still, the way that employment becomes increasingly insecure and poorly paid appears as the natural and inevitable result of abstract and inexorable technological change, rather than the product of choices and/or a system of exploitation. Historical comparisons, with a pre-capitalist world, might help expose the consequences of those of these assumptions for how we view our situation.

More strikingly, the role of work as a primary source of social and personal identity is virtually treated as a given: there is a recognition that this will need to change in future – the work is going to vanish, so we’ll need new foundations for our sense of self fairly sharpish – but no acknowledgement that in any case it’s a relatively new phenomenon. One thing a classical comparison can offer is clear evidence that work is not intrinsic to conceptions of human existence, or necessarily seen in positive terms; ancient ideas offer alternative models, including a powerful notion that leisure (hitherto confined to the privileged in existing forms of society, but perhaps now to be extended much more widely) is more essential to a full (and fully human) life. It’s an interesting parallel to the exploration of similar themes in Iain Banks’ Culture novels, presenting a post-scarcity society in which most feel themselves set free to develop their full potential (with just a few, as in The Player of Games, longing for the primitive delights of high-stakes competition and crushing victory, a return to the Heroic Age).

But, as Carol Atack (@carolatack) pointed out on Twitter, ancient discussions of the Golden Age don’t just offer positive visions of the life of leisure; they offer debates about the nature of utopia and its dark side. As Plato explores in The Statesman, the Golden Age in which humans live a life of ease alongside the gods is inextricably bound up with a loss of autonomy and political agency – it risks becoming the existence of a domestic pet, kept in meaty chunks because of affection or whim but always at the mercy of a vastly more powerful being who controls the tin opener; better than the life of the pig or the calf, but not qualitatively different. If the present problem is conceived as a need to reconcile ourselves to the end of work as a means of apportioning resources and establishing social status, while leaving everything else in place, then this risks giving Zuckerberg, Thiel, Musk and the rest the position of gods in this future society, while the best we can hope for is to grow fat and lazy indoors, watching the world through a pane of glass…

September 15, 2016

When I Was A Lad…

It’s the week before my first week of teaching in Exeter (a week earlier than I’m used to, creating an unfortunate clash with the Deutsche Historikertag in Hamburg, so it’s actually going to be my first half week of teaching…). Busy uploading module (not ‘unit’ or ‘course’; must remember that) information onto ELE, learning the relationship between seminars and study groups, revising the ILOs according to house style, checking availability of e-books, re-writing guidance on source analysis exercises, navigating SRS to send out messages, trying to grasp the workings of BART and RECAP, and wondering where I put my copy of the guide to local acronyms. I dunno, in my day you got a photocopied bibliography in the first lecture if you were lucky, none of this spoon-feeding and eDucation nonsense…

Perhaps it’s my imagination, or the consequence of following too many links on HE matters on Twitter, but it does feel as if this has been the year of academics (and others) complaining about Students Today (harrumph): their instrumentalism, their narrow-mindedness, their addiction to social media, their failure to buy books, their excessive sensitivity, their obsession with identity politics, their inability to address emails properly, their homogeneous fashions and terrible taste in music. Or, to put it bluntly, their general failure to Be Like We Were, and yet to expect this to be accommodated. I mean, seven of my new personal tutees identified themselves as dog rather than cat people: how am I supposed to work with this material?

There’s a widespread tendency in discussions of education, at any level, to project one’s own experience of it onto the rest of the world – always dressed up as a real concern for teaching methods and standards, and probably in most cases sincerely meant as such. This is very noticeable indeed in the current debates about the proposed return of the grammar school, with lots of fairly intelligent, more or less academic types arguing about the best system for nurturing today’s fairly intelligent, more or less academic children. Higher education discussions follow similar patterns: an excessive focus on the more traditional and elitist courses and institutions, perhaps, because that’s what politicians and journalists tend to have experienced, and on conventional patterns of study (sorry, FE and part-timers, *we* all did ‘proper’ full-time BAs in our late teens; nothing against you, we just don’t tend to remember your existence very often).

But even we impeccably liberal, open-minded academics have a habit of assuming that our students are basically like us – or ought to be; or at least we have a clear sense of how they ought to learn, which may be founded on little more than our own experience of learning (positive or negative). Sometimes this can be an advantage; I surely can’t be the only lecturer with a profound instinctive sympathy for the student with imposter syndrome who absolutely loathes having to say anything in class, and have therefore developed different techniques for class discussion to try to make things easier for such students because I know it would have been good for me to talk occasionally, however much I hated it… But we have to remember that they’re not all like that, not all like us. Products of a different social era, of a different level of technology, a different culture from our own student days – and with the expansion of higher education, even in places like Bristol and Exeter generalisations about “the typical student” have much less validity than even a decade ago, let alone a quarter century.

I believe that students are our future – and since it looks increasingly like a scary, dystopian sort of future, we need to teach them bloody well in order to show the way. This doesn’t imply that we need to ditch everything we know about learning and teaching on the basis that it’s old and therefore irrelevant, but simply to stop assuming that we already know all we need to know – and to drop the condescending attitude when students suggest something different. They may be wrong – we all want things that aren’t good for us sometimes – but so may we. We have wisdom to offer (“The Dalai Lama and I…”), and the benefits not only of experience but of professional skills in reflecting on that experience, analysing it and drawing lessons from it – but we need to draw the right lessons, for our students and not just for ourselves projected onto our students.

To take just one example: it’s a pretty safe bet that the vast majority of my students are going to be better adapted to technology than I am, so who am I to tell them to put down their iPads and pretend they’re back in the 1980s when they’re in the lecture theatre? But, in the spirit of Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations, I would argue that my experience of a world before the Internet offers the possibility of a critical perspective on present forms of knowledge and techniques of research, on what’s currently lost or obscured as well as what’s gained, from which they can learn. Forcing them back to physical books and old-fashioned lectures alone makes no sense; my job is to make sure that the lessons of critical thought and analysis, how to extract information and meaning from a mass of irrelevance and tedium, that we elderly and middle-aged people learnt by sitting through lectures and wading through monographs, don’t get lost in the shift to new forms of communication and information management.

The start of term always seems, understandably enough, to provoke thoughts about my own student days. Often this is in the form of the Nietzschean eternal recurrence: how would I feel about having to do it all over again, either in exactly the same way (oh god…) or given the chance to do things differently (what are the chances that I’d manage any better second time around? Limited…). But there’s an interesting variant: how would I feel about reliving my student days now, rather than returning to the 1980s? And I think the only sensible conclusion from such a thought experiment is the realisation not only of how different things are today, but also of how limited our knowledge actually is of what our students are going through, once we stop assuming that they’re simply undeveloped versions of ourselves…

August 30, 2016

Two-Edged Sword

Over on Twitter – as ever, a reliable source of evidence to confirm one’s most pessimistic, dark-night-of-the-soul judgements on humanity – an alleged artist is protesting loudly about being banned from the Edinburgh Fringe for being “too political” in her support of Palestine and criticism of Israel using the delightful hashtag #holohoax. A supporter responded to a critical tweet by demanding to know whether the critic had ever properly looked into the claims of Revisionists, attaching a link to a video of a lecture by David Irving with the hashtag #thucydides – and responded to a criticism of that by yours truly with the line “Revisionist history is not smearing, ask Thucydides if his histories concur with Cleons?”

I’m not sure if this is the first time that Thucydides has been expressly evoked in the cause of Holocaust denial (there are some significant examples of engagement with his ideas in the literature on the historiography of the Holocaust, above all the work of Pierre Vidal-Naquet – one of the things on my ‘to do’ list is writing up my paper from a conference in Strasbourg that looks at some of this and the wider ‘historiography of trauma’ theme) but it does seem all too depressingly obvious. Just as the term “revisionist history” is intended to make the enterprise seem virtuous and indeed authoritative – proper historians look at accounts critically and revise existing views constantly, so clearly it’s the partisans of the Holohoax who are abandoning professional standards of objectivity in favour of politically-motivated dogma – so David Irving is placed in the tradition of the sceptical and impartial Thucydides, refusing to accept received wisdom but insisting on questioning everything without fear or favour. Dissension from mainstream opinion thus becomes a sign of one’s fearless independence and hence trustworthiness.

Of course this works best if you don’t know much about Thucydides besides his inherited reputation for objectivity and reliability. Certainly his account of events differed from that of Cleon – but Cleon made no claims to be any sort of historian, and more importantly it is precisely Thucydides’ depiction of Cleon where many commentators have felt most concerned about whether he was as objective as he claimed. Somehow I don’t think that the intended message was “Revisionist history is like Thucydides: a politically-motivated hatchet job masquerading as a reliable historical account”. Thucydides is a more ambiguous and problematic example than a simplistic evocation of his reputation tends to recognise; is his demolition job on the story of the Athenian tyrannicides a noble exercise of critical historiography, concerned solely with the truth, or an underhand oligarchic assault on one of the founding myths of democracy – or, most obviously, both?

August 26, 2016

The Man Who Knows

What would Thucydides think of the current debate about the banning of the burkini in various French coastal resorts in the name of secularism? On the one hand, there is his notorious scepticism about religion and its manifestations, which, coupled with his equally notorious conservatism and indifference towards women, might have inclined him to side with those who see the costume as a symbol of intolerance and ignorance. On the other hand, there are the words he puts into the mouth of Pericles in praise of Athens as a liberal state where people’s private lives and behaviour are their own business so long as they obey the law, coupled with his keen ear for the hypocrisy of politicians and the lamentable tendency for society to fragment into factionalism and mutual intolerance.

The simple answer is of course that we haven’t the faintest idea; the issue is not one that remotely translates into the context of fifth-century BCE Greece, so the only way of ascribing an opinion to Thucydides is to abstract general ethical and political principles from his work (difficult enough, given that almost all statements along those lines are put into the mouths of characters of dubious trustworthiness, rather than offered as his own views) and then argue about how these might apply to a specific problem. In other words: if we assume that Thucydides endorses Pericles’ stated principles on public and private behaviour, then we can make a case for how a given case could be understood in terms of those principles (which would tend to point towards freedom of dress as well as expression). But it’s all pretty tenuous, and a long way from being able to state that this is what Thucydides thought on the matter. So for the most part such discussions focus on those topics, like war and politics, where we can feel confident that Thucydides did actually have opinions even if they’re less clearly stated than we might wish.

I should have said: the only defensible way of ascribing an opinion to Thucydides – because of course there are plenty of examples of people ascribing opinions to him regardless. He prompts his readers to expect to recognise their own times in his account of past events – and that seems to encourage some of them to imagine that therefore he will have something to say about everything, regardless of the degree of separation from the world of the Peloponnesian War. The long tradition of constructing Thucydides as an authority figure is bound up with a persistent habit of imagining his character and personality; this generally serves to bolster his authority as historian and/or political analyst – he’s the austere lover of truth, the sceptic, the exile etc. – but clearly it creates the possibility of imagining his views on different issues on the basis of his perceived attitudes and sensibility.

My starting assumption is that this is basically (or at least primarily) a modern phenomenon. Certainly the examples that come immediately to mind are modern: W.H.Auden’s claims about what “exiled Thucydides knew” about dictators and their rhetoric, Bob Dylan’s somewhat, erm, imaginative account (see John Byron Kuhner’s Eidolon piece) of the way he shows “how human nature is always the enemy of anything superior”. In previous centuries, ideas about Thucydides’ character were deployed above all to reinforce the authority of his work; today, one might argue, such ideas are deployed in order to claim his authority for the author’s own views about the world. ‘Realism’, for example, becomes less of a theoretical proposition about inter-state relations and more of a sensibility, on the basis of which we can argue that Thucydides would have cheered for Mourinho’s Chelsea (Mark I) and listened to Aphex Twin.

The most striking and interesting example of such imaginative reconstructions that I’ve encountered up until now is Victor Davis Hanson’s 2001 piece ‘An interview with General Thucydides’ (reprinted in his An Autumn of War from 2002), which constructed a Thucydidean case for a belligerent US response to 9/11 by quoting lines from his work as responses to questions from a journalist about the world situation. Rather than Hanson offering the argument that Thucydidean principles of inter-state relations point towards the need for immediate retaliation, he makes Thucydides offer such an argument himself. The words themselves are genuine enough (translation issues aside), it’s the de-contextualisation and re-arrangement of them that might provoke accusations of tendentiousness.

The latest example of an imagined Thucydides goes much further in projecting the author’s ideas about contemporary issues onto the ancient Greek, by claiming to present what he actually thinks about such things without worrying about quotes. Thucydides in the Underworld, by one J.R. Nyquist (who seems to spend much of his time warning against imminent Russian aggression, the Muslim invasion of Europe (Russian-backed) and the Fourth World War), imagines Thucydides’ spirit being constantly disturbed from its rest in Hades by the arrival of his deceased admirers, seeking his approval for their own works of history – an increasingly miserable and unimpressive crowd, especially with the advent of modernity, who seem ever more to miss the real point of his account and instead believe in their own superiority as the most evolved men (echoes of Nietzsche here, I think).

Thucydides longed for the peace of his grave, which posthumous fame had deprived him. As with many souls at rest, he took no further interest in history. He had passed through existence and was done. He had seen everything. What was bound to follow, he knew, would be more of the same; but after more than 23 centuries of growing enthusiasm for his work, there occurred a sudden falling off. Of the newly deceased, fewer broke in upon him. Quite clearly, something had happened. He began to realize that the character of man had changed because of the rottenness of modern ideas. Among the worst of these, for Thucydides, was that barbarians and civilized peoples were considered equal; that art could transmit sacrilege; that paper could be money; that sexual and cultural differences were of no account; that meanness was rated noble, and nobility mean.

The problem? The triumph, not of democracy, but of the belief that democracy had triumphed; excessive confidence in human capabilities, and hence neglect of the real threat to civilisation, nuclear proliferation:

Men built new engines of war, capable of wiping out entire cities, but few took this danger seriously. Why were men so determined to build such weapons? The leading country, of course, was willing to put its weapons aside. Other countries pretended to put their weapons aside. Still others said they weren’t building weapons at all, even though they were.

Would such weapons be used? The example of Melos shows that it’s inevitable. Moreover, whereas Athens just had to endure Alcibiades, every free and prosperous country in the modern world suffers from a plague of “human beings with oversized egos, with ambitions out of proportion to their ability, whose ideas rather belied their understanding than affirmed it… Instead of being exiled, they pushed men of good sense from the center of affairs. Instead of being right about strategy and tactics, they were always wrong.”

Perhaps because he’s had two and a half millennia to think things over a bit more, Thucydides’ original optimism about the capacity of history to teach people to understand the world has been replaced by despondency, and a belief in absolute determinism; human beings repeat the same actions, again and again, and the only lesson of history is that no one ever learns lessons from history:

Society is slowly built up, then wars come and put all to ruin. Those who promise a solution to this are charlatans, only adding to the destruction, because the only solution to man is the eradication of man.

The generations most in need of his teaching, he now realises, are those most likely to ignore it, and so re-enact the events he described.

Seeing that time was short, and realizing that a massive number of new souls would soon be entering the underworld, the shade of Thucydides fell back to rest.

It’s an interesting counter-point to Graham Allison’s ‘Thucydides Trap’ idea; in that case, various commentators have argued that the existence of nuclear weapons is precisely why the scenario of escalating tensions between established and rising power leading to war is less likely to happen than the alleged model of Thucydides and the 12 out of 16 case studies suggest; here, it’s the existence of nuclear weapons that will bring about Melos For Everyone.

In lots of ways, this image of Thucydides as the Man Who Knows, who really understands the dynamics of human behaviour and history, even if most people are incapable of accepting his insights, is utterly conventional. The two aspects that seem odd are, firstly, Nyquist’s claim that interest in Thucydides has recently declined – on the contrary, a strong case can be made that he’s more widely cited as an authority than ever before, albeit mostly not by historians – and secondly the passing denunciation of modernity in general, cited above.

We could at a pinch equate the line from Nyquist’s ‘Thucydides’ about meanness being rated as nobility and vice versa to the actual Thucydides’ account of the collapse of agreed values in the Corcyrean civil war, though this raises questions about the definition of ‘nobility’. It’s also a standard interpretation that Greek thought was built around polarities – Greek/barbarian, male/female etc. – so one could imagine that an ancient Greek might be disturbed by a different system of conceptual order, different ideas about gender etc. – but it’s not an idea that has much basis in Thucydides’ actual writings, which almost entirely ignore such issues. Moreover, the claim about his suspicion of paper money resembles nothing so much as the line invented by Friedrich von Raumer in the anecdote cited by Reinhart Koselleck to illustrate the collapse of historia magistra vitae that I’ve quoted so many times. And as for the idea of art transmitting sacrilege – you what? I suppose Pericles does say something about art…

If I had the time, I’d be tempted to revive my idea for a picaresque novel in which Herodotus and Thucydides go back-packing across Europe, reflecting philosophically on historical change, the nature of the human and the music of Hubert von Goisern.* Of course, my Thucydides would not be the curmudgeonly conservative of the mainstream interpretation, let alone of Nyquist’s fantasy, railing against multiculturalism and modern art – and even if the likelihood of my working on a novel any time soon is basically zero, I really do need to find time for a shorter piece that I have in mind on how he can be reclaimed for radical politics.

But my Thucydides would also be unmistakably a fictional character, rather than desperately denying this for fear that this would undermine his usefulness as a source of authority and counter-cultural icon. Ventriloquism, one might say, rather than sock-puppetry…

*I’d be perfectly happy to make this a classic trans-American road trip instead, if anyone feels like paying expenses for the necessary research.

August 23, 2016

Power to the People? Or the Persians?

One of the less remarked-upon policies of the UK Labour Party in recent years has been to restore the relevance of the Athenian political system as a workable analogy for contemporary democracy. Besides all the dramatic changes in ideas and ideology since the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, charted at length by scholars like Paul Cartledge and Wilfried Nippel, the fundamental objection to the deployment of classical comparisons has always been the modern switch from direct to representative democracy, from decisions being taken directly by the votes of the demos to decisions being taken by their elected representatives. The consensus – leaving aside recent arguments that the internet now makes a return to direct democracy possible – has been that this is the only practical means of realising the ideals of democracy in the complex world of modernity.

Such a position always runs the risk of looking much too like technocracy, or a kind of oligarchy, giving the people the illusion of power while keeping it as much as possible in the hands of the elite in practice – a modern version of Thucydides’ judgement on the dominance of Pericles in what only appeared to be a democracy. So, especially when those representatives seem to be making a pretty shoddy job of things and/or going against the expressed wishes of the majority, there’s always a case to be made for restoring real power to the people, not only to address their frustrations but in the belief that this will lead to their energetic engagement, with positive results (what we might term the Herodotus principle, that Athens began its rise to greatness when its people took power into their own hands). This seems to have been the impulse behind the changes to the rules governing the election of the Labour leader; it’s certainly one of the claims being made about Jeremy Corbyn’s impact in that role; and now both the candidates for this year’s round are proposing in different ways to extend the role of the party membership in making policy and telling their elected representatives what to do. At which point, classicists can start rubbing their hands with glee…

Rather than firing up all my “Thucydides highlights tendency for people to fall into group-think and make terrible decisions based on emotion and over-optimism” references, however, I’ve found myself this morning thinking instead about the occasions when the Athenians quite consciously followed a technocratic approach: waging war. Not even the most committed ancient democrat thought that military decisions should be made on the basis of a vote; the demos voted on strategy – whether or not to make war, whether or not to send an expedition to Sicily – and voted for the generals who would put those strategic decisions into practice as they thought was best. Arguably this was a recognition both of the specific qualities required for the job, and of the fact that democratic deliberation wasn’t suitable for the battlefield, whether because of its susceptibility to emotion or simply because it needed so much time. Similarly, detailed negotiations with other states were handed over to ambassadors (although of course the treaties themselves needed to be properly ratified).

The relevance of this to the current state of the Labour party? Nothing, perhaps; the situations are incomparable in so many ways. It’s also easy to see how a case for recognising the essential role of expertise in certain areas can easily slide into the position of Socrates (or Blair…) that insists on excluding the demos from any meaningful decisions on the basis of its lack of expertise.

Perhaps the most striking difference between then and now is that the Athenians were for the most part making decisions about their own affairs, without much need to worry about how they looked to others; they might have been wiser to worry slightly more about the effect on some of their allies/subjects, Thucydides implies, but they were able to kick them into line when necessary. The Labour Party doesn’t have that luxury; it needs policies that are attractive to a broader constituency – that can, so to speak, bring the Persians onside, whereas at the moment they are showing every sign of going over to the Spartans for the long term – and so there might be something to be said for listening to the people with experience of winning over Persians…

August 16, 2016

Let traitors (and pedantic academics) sneer…

Another entry for the ‘Fake Thucydides Quotations’ file, passed on to me by the great Thucydides scholar W.R. Connor (who’s now posted something about it on his blog).

Προδότης δεν είναι μόνο αυτός που φανερώνει τα μυστικά της πατρίδας στους εχθρούς, αλλά είναι και εκείνος που ενώ κατέχει δημόσιο αξίωμα, εν γνώσει του δεν προβαίνει στις απαραίτητες ενέργειες για να βελτιώσει το βιοτικό επίπεδο των ανθρώπων πάνω στους οποίους άρχει.

A traitor is not only one who reveals state secrets to enemies, but it’s also that person who, while he holds public office, intentionally[?] does not take the necessary actions to improve the standard of living of the people over whom he governs. [translation by W. Gary Pence]

What’s interesting about this one is that it appears in modern Greek – and, so far as I can ascertain, virtually only in modern Greek; yes, there’s the usual problem of having to guess at possible translations, so I can’t guarantee the results, but so far the only English versions I’ve found appear embedded in Facebook pages and blogs (e.g. here) that are otherwise entirely in Greek, or on websites that are definitely based in Greece (e.g. here).

Researching the background of this fake is rather hampered by my very limited grasp of modern Greek, but the earliest example I’ve found on the internet appeared on 1st February 2001 as the tagline of a commentator called Kerberos in an online discussion of, erm, cesspool efficiency (it reappears in various posts he makes on heating systems as well). No fuss is made about the quote – it’s just there, as part of the commentator’s online self-presentation, in exactly the same way that other people have ‘Happiness depends on freedom…’ or ‘The strong do what they will…’ as their taglines – and so it’s a reasonable assumption that this is not Kerberos’ own invention; even if it is, he (I assume it’s a he) makes no mention of it whatsoever, and certainly doesn’t show any sign of trying to propagate a new Thucydides quote. My best guess is that it’s been taken from another source, but for the moment I’ve no idea what.

This is a quote that seems to hang out in faintly dubious, and certainly very odd, company. In 2007, for example, it appears on the front page of the website of the Beekeepers’ Association from Pella, in the Greek province of Macedonia; no obvious connection to bee-keeping (although, given that the Romans were happy to conceive of the hive as a political institution, one might develop some sort of interpretation along these lines of the role of the drones) – but then you could say the same of the video of Dorothy King talking about the tomb at Amphipolis and the fact that FYR Macedonia has absolutely no connection to the historical Macedonia, which features further down the page. Apiculture always has a political dimension…

In 2008 it starts appearing as part of the permanent architecture of different blogs, some of which clearly have a political agenda (e.g.this one); from 2009 it appears more frequently as a tagline; in 2010 it appears in a list of political quotes; in 2012 it’s posted on the Facebook page of ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟ ΑΡΧΕΙΟ – where commentators immediately observed that it’s completely spurious, but without any success. I haven’t found any example where the line is not attributed to Thucydides – nor any example of a more precise reference to the text (which is of course understandable, given that there’s no trace of anything like this line anywhere in Thucydides that I can think of).

Bob Connor suggested that the quote might have been invented as a left-wing sneer against Tsipras; it’s clearly a lot older than that – and part of the tragedy of Greek politics in recent years is that it works just as well as a condemnation of Tsipras’ predecessors. It’s difficult to see anything specifically Thucydidean about it; indeed, one might argue that it’s clearly a sentiment appropriate to political rhetoric in peacetime, calling for political leaders to work for the people rather than enjoying power for its own sake (it might be more plausible if attributed to someone like Demosthenes, for example, rejecting accusations of corruption and treason and then turning them on his opponents through a neat trick of redefinition).

But of course the fact that Thucydides is an implausible source for such a quotation has never stopped anyone before. It’s in the same class as the well-worn attribution to him of the line that’s actually associated with Solon (e.g. in Plutarch): Justice will not come to Athens until those who are not injured are as indignant as those are. Presumably it’s the idea of Thucydides as illusionless, cynical critic of democracy and its failings: politicians are self-serving never to be trusted, politics doesn’t work very well, we can’t really hope for justice in this world.

I do wonder whether there may be a general trend in this direction – plenty of citation of more genuine lines from Cleon about the limitations of democratic deliberation – to match the general mood of anti-politics, in contrast to the idealistic tradition of citing Pericles’ Funeral Oration and its noble liberal values…

August 13, 2016

Luxurious Posterior

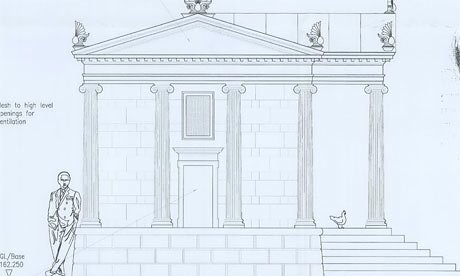

One of the most striking items in this morning’s newspaper was the fact that the only non-anonymous funder of the aggressive grouse-shooting lobby organisation You Forgot The Birds, hedge fund manager Crispin Odey, houses his chickens in a stone edifice modelled on a Greek temple (I missed this story when the plans were first identified via his local council’s planning department website).

Partly because I recently finished revising an article on the idea of frugalitas in the Roman agronomists, this immediately called to mind Varro’s discussion of bird houses alongside other forms of pastio villatica. The theme of a contrast between ancient frugality and modern luxury is put centre-stage from the beginning, as Varro’s characters set out the different divisions of the subject:

Each of these three classes has two stages: the earlier, which the frugality of the ancients observed, and the later, which modern luxury has now added. For instance, first came the ancient stage of our ancestors, in which there were simply two aviaries: the barn-yard on the ground in which the hens fed — and their returns were eggs and chickens — and the other above ground, in which were the pigeons, either in cotes or on the roof of the villa. On the other hand, in these days, the aviaries have changed their name and have become ornithones; and those which the dainty palate of the owner has constructed have larger buildings for the sheltering of fieldfares and peafowl than whole villas used to have in those days. (3.3.6-7)

This is accentuated in Varro’s description of his own aviary at Casinum:

Between these lies the site of the aviary, shaped in the form of a writing-tablet with a top-piece, the quadrangular part being 48 feet in width and 72 feet in length, while at the rounded top-piece it is 27 feet. Facing this, as it were a space marked off on the lower margin of the tablet, is an uncovered walk with a plumula extending from the aviary, in the middle of which are cages; and here is the entrance to the courtyard. At the entrance, on the right side and the left, are colonnades, arranged with stone columns in the outside rows and, instead of columns in the middle, with dwarf trees; while from the top of the wall to the archway the colonnade is covered with a net of hemp, which also continues from the archway to the base. These colonnades are filled with all manner of birds, to which food is supplied through the netting, while water flows to them in a tiny rivulet. Along the inner side of the base of the columns, on the right side and on the left, and extending from the middle to the upper end of the open quadrangle, are two oblong fish-basins, not very wide, facing the colonnades. Between these basins is merely a path giving access to the tholos, which is a round domed building outside the quadrangle, faced with columns, such as is seen in the hall of Catulus, if you put columns instead of walls. Outside these columns is a wood planted by hand with large trees, so that the light enters only at the lower part, and the whole is enclosed with high walls. Between the outer columns of the rotunda, which are of stone, and the equal number of slender inner columns, which are of fir, is a space five feet wide. Between the exterior columns, instead of a wall there is a netting of gut, so that there is a view into the wood and the objects in it, while not a bird can get out into it. In the spaces between the interior columns the aviary is enclosed with a net instead of a wall. Between these and the exterior columns there is built up step by step a sort of little bird-theatre, with brackets fastened at frequent intervals to all the columns as bird-seats. (3.5.10-13)

Odey’s chicken coop seems to fit firmly within this tradition of ridiculously extravagant farm buildings, costing far more than the birds they contain can ever be worth; a perversion of the good old Roman tradition of parsimony (even if, as scholars like Ingo Gildenhard have argued, the idea of frugalitas as the cardinal virtue is largely if not entirely an invention of Cicero, there is certainly an obsessive concern with cost management in Cato’s work on agriculture, carried on in a more complex and satirical form by Varro).

Where Odey goes beyond even the most decadent of Roman aristocrats is in dedicating such expense not to peafowl or nightingales but to the humble chicken. Even in Varro, full of detail about the luxurious behaviour of modern Romans, the discussion of chickens is thoroughly pragmatic and practical; this is part of the villa enterprise focused on returns, rather than the more elusive goal of combining fructus and voluptas in a single activity.

It is not unproductive in the straightforward way that a game park or an aviary is, a form of consumption available only to the fabulously wealthy; it takes the additional step of parodying the sort of humble activity practised by countless ordinary farmers in their back yards. “Oh yes, I keep a few chickens…” It reminds me of the Elder Pliny’s complaint that, whereas once vegetables were “the poor man’s meat”, they had now become luxury items far beyond the reach of the mass of the population. If they were ever conceived of as an economic enterprise rather than just an opportunity to show off, how much would the eggs of Odey’s chickens cost..?

July 31, 2016

The Exercise of Influence

I’m a little disappointed that the Chilcot report – at least if its text search facility is as reliable as has been suggested – contains no mention of Thucydides. True, there’s no established tradition in the UK of drawing foreign policy lessons from the Peloponnesian War, unlike in the US where it’s a set text for high-powered military officers as well as being a favourite of various associates of the Project for a New American Century, above all the influential Donald Kagan. But given the involvement in the inquiry committee of Martin Gilbert, historian of 20th-century war, and Lawrence Freedman, a leading figure in war studies, one might have expected at least a passing gesture. Alas, word searches for terms like ‘Athens’, ‘Sparta’, ‘Nicias’, ‘Syracuse’ and ‘Sicily’ all return blanks (though I was pleased to see that “shambles” occurs about thirty times).

It now seems, however, that I may have been too hasty in this judgement, and too superficial in my expectations; according to a blog by Glen Rangwala of Cambridge, ‘The Chilcot Report: the longest work of academic history ever’, Thucydides and his ideas in fact permeate the entire enterprise, not through a few glib citations, but by establishing its methodological principles:

The academic discipline that Freedman’s and Gilbert’s books inhabit began with what is still perhaps the greatest history of a war ever written, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. Indeed, Thucydides provides the subject matter of a whole chapter of Freedman’s Strategy: A History, a mammoth text published in 2013, and written at least in part during the Chilcot inquiry. While the report easily eclipses Thucydides’ eight books in length, it replicates its approach of recording meticulously the words spoken (or, in this case, written) by politicians, noting the differences of their perspectives, extricating their reasoning and tracing their consequences, both intended and unintended. Moreover, the report could have been seen as following, in its own way, one of Thucydides’ most famous maxims: that the history of a war will have served its purpose “if it is judged useful by those who want to have a clear view of what happened in the past and what – the human condition being what it is – can be expected to happen again some time in the future”, as Jeremy Mynott’s superb recent translation puts it.

What is under scrutiny is therefore the political reasoning of leaders, traced through presenting the memos, minutes of meetings, parliamentary debates and press interviews surrounding the use of military force in Iraq…

In one specific, but rather important, respect, as a characterisation of Thucydides’ work this is completely wrong. It’s not just that Thucydides does not meticulously record the words of his various characters; it’s the fact that, on the contrary, he openly admits that he was not able to record the words accurately in every case, and has therefore made the speakers say what seemed appropriate according to their situation. It’s one of the ways in which his approach to historiography is thoroughly un-modern, and troubling for many modern historians, to the extent that some (Kagan, for example) try desperately to interpret his methodological statements as charitably as possible – and others are happy to suggest that Thucydides was more like a dramatist or a mythographer. If the idea of Bush saying “Yo, Blair!” seemed too good to be true, in Thucydides it would certainly be much too good to be true.

But – and this is where I think Rangwala hits on something entirely right, even if by a questionable route – the aim of this procedure is exactly the same as Chilcot’s properly meticulous approach: to withhold explicit judgement or commentary, and to make the characters condemn themselves out of their own mouths. Pericles, Cleon, Nicias, Alcibiades and the rest speak, and we deduce not only their thinking but also their semi-concealed thoughts and their characters, without immediately perceiving that this is simply how Thucydides has made them present themselves. Blair, Straw, Short and the rest of them speak, and we deduce not only their thinking but also their semi-concealed thoughts and their characters, without immediately perceiving that this is simply how the Chilcott team has made them present themselves, not by inventing any words but certainly in the way they have chosen what to excerpt and how to arrange it. The reader appears to be left to make up his or her own mind, while being subtly manipulated towards a particular line of interpretation.

Further, the report, like many parts of Thucydides’ account, “focuses on the beliefs that [Blair] and others held, and what the consequences of those beliefs were.” It aims to reflect on the complexity of events and their interaction.

The Chilcot report is probably one of the most thorough and exhaustive accounts of the politics of a specific conflict in the history of the study of international relations. If it is read not as the evaluation of an individual leader or as a set of narrow policy prescriptions but instead as a critical evaluation of a way of thinking about foreign policy, it takes on a political force that goes beyond the specific context of the account. Like all good academic analysis, it has resonance beyond its own immediate moment.

That resonance, however, tends less towards a set of clear judgements and policy recommendations than towards a world view, that events are complicated and difficult to predict – but that individuals can always make things worse. Pessimism about prediction, optimism about the capacity for critical analysis to make sense of the past (if not the present); all very Thucydidean. As Rangwala notes, it’s questionable who’s actually going to have the stamina to read the Chilcot Report – in which case it’s worth emphasising his observation that Thucydides is substantially shorter, and so an excellent means of grasping the same essential truth about the world.

July 21, 2016

I’m Backing Britain!

One of the things I have always found rather weird and off-putting about German academia is the way that some professors include a section in their CVs about the Rufe – the offers of chairs at other universities – they have turned down. I understand, intellectually, why this happens: in many cases, especially in the past, a professor stayed at the salary level at which they were originally appointed, unless they could wave an offer from somewhere else at the university management and negotiate a better deal, so it was only rational to apply elsewhere on a regular basis – and clearly it continues to be a means of arguing for more support staff, more research money and the like, as well as a recognised indicator of social capital. Further, if everyone knows that every job will attract applications from a load of high-powered established professors who don’t really want it but will take at least six months to play this possible future university off against their current university before declining the offer – which is why, from a UK perspective, German appointment processes take a staggeringly long time – then the people who actually end up taking the jobs, two years later, won’t feel at all embarrassed that it’s all out in public: you weren’t competing on a level playing field, so winning by default, so to speak, isn’t an issue.

So, in context, it’s perfectly intelligible – but it still makes me feel uncomfortable. Partly, it’s a reminder of how hierarchical and inegalitarian the German academic system can be, certainly in the humanities: it’s bad enough that there are so very few permanent positions and so many highly qualified people competing for them (see fascinating article from 2013 on how academia is like a drug gang in this respect), but it’s worse when those who already have jobs – and so don’t have to worry about the fact that the appointment process drags on for years – continue to play the market and so slow the whole thing down. I’ve heard it suggested that the reason why many German universities no longer pay travel expenses for job interviews is to try to discourage applicants who aren’t serious about the position – but that further discriminates against those in marginal, fixed-term contracts as opposed to well-paid established professors who can more easily afford the train fare.

Partly, I may be projecting the British experience – where in most cases a department desperately needs to fill a vacancy in order to keep the show on the road, so offering a job to someone and having to wait six months for them to make up their mind is a total nightmare – onto a completely different context; if the Faculty knows it will take two years to fill a position because that’s what it always takes, it’s prepared for that, and my sympathies for departments being messed around by candidates are misplaced. Finally, I suspect I am just being incredibly English (or maybe British); it offends against all sorts of ideas of fair play, modesty, self-deprecation and so forth to advertise that one turned down a chair (the British tradition is much more focused on outward equanimity and inward seething resentment from those who get passed over – but that’s probably true in Germany as well).

So, it’s with the aim of demonstrating my partial integration into German academic mores that I now proudly (well, half-heartedly) announce that I too have turned down a Ruf to a German chair – but I’m still being thoroughly British about it by (a) not telling you which university (though I don’t think the confidential appointment process is ever very confidential here) and (b) declining the invitation within a day of receiving it, rather than nine months. I am a little nervous that this – the rapid Ablehnung, that is, rather than the public announcement – may be taken as a sign of disrespect; perhaps I ought to embark on protracted negotiations with them and with Exeter, to show that I was serious and that they were right to make me the offer.

That’s not going to happen. I was absolutely serious when I applied (however many years ago that was…) and at the interview; I really would like to experience a different higher education system properly, rather than just as a visitor, and while I’m perfectly aware that the grass always looks greener on the other side, there are many things about German universities that are very attractive – especially now that I’m threatened with having my European identity taken away… But, having accepted the offer of a position at Exeter with alacrity just a couple of months ago, I’m certainly not going to attempt to change course now, let alone play with the possibility as a bargaining chip.

And if it had been a straight choice a couple of months ago, rather than everything being determined by timing..? Still Exeter, I think; the prospect of working with some really exciting new colleagues with whom I share a load of interests – not just in Classics & Ancient History but also on the political theory side – outweighs the prospect of getting to grips with a totally different system as the all-powerful Professor, with added Europeanness – especially as this way I get to maintain my German links via ongoing collaboration with colleagues in Berlin. And, while Brexit does create the possibility that, if all goes utterly pear-shaped, I’ll be looking back in a few years’ time wondering about what might have been, the fact that I made it to third place on the list for a proper German academic position means that I can always try again in future if that seems the right way to go.

Of course, what I should now be doing – given all the recent rhetoric about accepting the Voice of The People, focusing on making Brexit the best possible Brexit in the best of all possible worlds, making Britain Great Again and so forth – is writing this up as a “Why I’ve Turned Down A Foreign Job Offer To Stay in the UK!” story. I’m sure there are going to be any number of “that’s it, I’ve had enough, I’m off to Canada” articles in the next few years, especially with various countries making noises about incentives to attract disaffected UK academics (they think they need incentives??). How better to bury my inconvenient involvement in the Remain campaign and to show that I’m now fully signed up to the glorious new order than to offer a counter-narrative..?

July 19, 2016

People’s Choice?

I have a piece up on Eidolon this week: Why Thucydides? As tends to happen, the moment it’s posted I immediately think of other things I might have said, and ways I might have said them better (and I don’t just mean the fact that every other sentence seems to begin with “But…”). I stand by the three main suggestions as to why Thucydides should be the go-to ancient authority for commenting on current politics and international affairs – his work invites such identification and comparison, there are long traditions of citing him as an authority, and we really want to believe that someone understands what the hell’s going on – but I can’t help feeling that there’s more going on. Herewith some further thoughts…

(1) Quotability: they may sometimes be spurious, or at least garbled, but Thucydides offers plenty of good one-liners. However, so do lots of other ancient authors (cf. the research I did on citations in anthologies and quote collections, the dominance of Plutarch etc.) – and it’s not as if they don’t get quoted: plenty of Aristotle, Plato, Plutarch etc. on Twitter (not so much Tacitus or Herodotus, though, and very little Livy).

(2) Subject matter: this seems to be more like it. Although there is the weird phenomenon of a Thucydides quote being used in a new agey motivational context, most of the time he is firmly associated with politics and war. Aristotle and Plutarch, on the other hand, seem to have been entirely subsumed by the ‘tomorrow is the first day of the rest of your life’ crowd: “Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all”; “Happiness depends on ourselves”; “Excellence is not an event, it is a habit” and so forth. Very inspiring, but unlikely to be brought to bear on US-China relations.

(3) The sort of chap you’d have a beer with. I’ve written about this before, but I think it stands: while T does have this scary and/or reassuring reputation as brilliant intellect who really knows what’s going on, he also appears as someone who knows because he’s been there himself. Especially in military circles (and since the 16th century…), the fact that T was actually a general and not just a pointy-headed intellectual has been put forward as a reason for trusting him. A Thucydides reference is a sign of manliness and military credibility, where any other author might come across as a bit intellectual.

(4) Rome: Total War.

(5) I told you it was a virus…

Neville Morley's Blog

- Neville Morley's profile

- 9 followers