Francis Berger's Blog, page 157

May 7, 2019

Alarm Bells: Democracy and The Rule of Law

Over the past few years, I have noticed that very few things alarm the Western Establishment as much as the perceived weakening of their cherished democracies and the rule of law. Alarm bells over democracy and the rule of law tend to ring loudest in the Western Anglosphere and the dark citadels of the European Union, and criticism tends to be directed at countries unwilling to wholeheartedly embrace the liberal/leftist worldview the aforementioned bastions of freedom and progress promulgate.

On the surface, democracy is designed to be a system of rule by laws, not individuals. Democracy is supposed to use the rule of law to protect the rights of its citizens, maintain order, and limit governmental powers. In theory, all citizens within a democracy are equal under the law. Perhaps most importantly, no one may be discriminated against on the grounds of race, religion, ethnic group, or gender. It is a human-centered form of government with no space for the transcendent.

This form of governance is desirable and appealing to the average modern person, and why not? People in the West have surrendered their spiritual and moral compasses and have allowed themselves to be utterly steeped in a limited humanistic and materialistic worldview. They have allowed themselves to be conditioned to believe in the goodness of our current democracies and the rule of law to the same extent Pavlov conditioned his dogs to believe bell-ringing signified mealtime.

All of this even though lived experience informs people that, contrary to what the system claims to do, democracy and the rule of law actually assaults citizens’ rights, creates chaos, and increases governmental powers.

The time to re-examine our conditioned assumptions regarding the weakening of democracy and the rule of law has come. Rather than grow apprehensive, we should begin to view all alarm bells the Establishment ring as signals that something Good might actually be occurring.

On the surface, democracy is designed to be a system of rule by laws, not individuals. Democracy is supposed to use the rule of law to protect the rights of its citizens, maintain order, and limit governmental powers. In theory, all citizens within a democracy are equal under the law. Perhaps most importantly, no one may be discriminated against on the grounds of race, religion, ethnic group, or gender. It is a human-centered form of government with no space for the transcendent.

This form of governance is desirable and appealing to the average modern person, and why not? People in the West have surrendered their spiritual and moral compasses and have allowed themselves to be utterly steeped in a limited humanistic and materialistic worldview. They have allowed themselves to be conditioned to believe in the goodness of our current democracies and the rule of law to the same extent Pavlov conditioned his dogs to believe bell-ringing signified mealtime.

All of this even though lived experience informs people that, contrary to what the system claims to do, democracy and the rule of law actually assaults citizens’ rights, creates chaos, and increases governmental powers.

The time to re-examine our conditioned assumptions regarding the weakening of democracy and the rule of law has come. Rather than grow apprehensive, we should begin to view all alarm bells the Establishment ring as signals that something Good might actually be occurring.

Published on May 07, 2019 03:22

May 6, 2019

I No Longer Read Pseudonymously-Written Blogs

And I will not read any more pseudonymously-written Christian/anti-liberal blogs going forward for one simple reason – I cannot shake my deeply held belief that writers and thinkers who write such blogs under assumed pen names essentially lack moral courage. In my mind, their unwillingness to support their ideas with their true, natural identities reveals a failure of character.

I have become increasingly convinced that the failure of character and lack of moral courage inherent in pseudonymous authorship likely causes spiritual harm for both the writer and the reader. Hence, I will no longer expose myself to anything written by anyone who works under a fictitious name online.

I addressed the topic in a

This brings me to the more general topic of pseudonyms, fake names, aliases, anonymity and the like. Although I respect medieval artists who purposefully chose anonymity as a way of glorifying God, the contemporary use of anonymity and aliases by artists, writers, and bloggers troubles me. I am not referring to individuals who use aliases but whose real names are publicly known, but to those secretive writers, thinkers, and bloggers who hide their authentic identities under noms de plume.

Of course, I understand the reasons why writers and bloggers use false names; many of them may hail from the academic world or some other vulnerable sector in which they cannot openly express their views for fear of censor, or even peril to their jobs. Yet, I cannot help pause for a moment and wonder, with the exception of whistleblowers, why do writers and bloggers bother making their views public if they lack the courage or the means to stand by their words? This applies especially to writers and bloggers who express anti-liberal, anti-leftist, and Christian views in their work. Perhaps I am being too harsh with this criticism and perhaps it is not my place to judge, but I believe this refusal to identify with these expressed ideas essentially reveals an immense failure of character and moral courage.

Put simply, those who rail against the evils of our modern world and make attempts to offer hope and guidance but refuse to put their names to their ideas are cowards. In my mind, their reluctance to stand by their words points to excessive self-concern, one that overrides the good they are saying or doing.

Of course, to write under one’s real name or an assumed name is a matter of personal choice. I am willing to accept that some writers believe it is the right thing to do, but this belief does not necessarily entail that writing pseudonymously is the right thing to do.

On the contrary, I am certain it is the wrong thing to do.

Having said that, reading blogs is also a matter of personal choice. Though I appreciate the fine work pseudonymous bloggers often offer, I can no longer support their decision to hide behind fictitious names. Thus, I have made the personal choice to avoid blogs with pseudonymous authorship going forward.

I don’t care to hear any more explanations, rationalizations, or justifications concerning the use of false names.

For me, the matter is simple:

Writers who are afraid to be Real should not be writing about Reality.

Note: This criticism is aimed chiefly at bloggers, writers, and thinkers, and not at pseudonymous commenters. Nevertheless, pseudonymous commenters would also benefit from considering the negative implications of using fictitious names. If you cannot develop the fortitude to openly speak your truth now, when do you expect to develop it?

I have become increasingly convinced that the failure of character and lack of moral courage inherent in pseudonymous authorship likely causes spiritual harm for both the writer and the reader. Hence, I will no longer expose myself to anything written by anyone who works under a fictitious name online.

I addressed the topic in a

This brings me to the more general topic of pseudonyms, fake names, aliases, anonymity and the like. Although I respect medieval artists who purposefully chose anonymity as a way of glorifying God, the contemporary use of anonymity and aliases by artists, writers, and bloggers troubles me. I am not referring to individuals who use aliases but whose real names are publicly known, but to those secretive writers, thinkers, and bloggers who hide their authentic identities under noms de plume.

Of course, I understand the reasons why writers and bloggers use false names; many of them may hail from the academic world or some other vulnerable sector in which they cannot openly express their views for fear of censor, or even peril to their jobs. Yet, I cannot help pause for a moment and wonder, with the exception of whistleblowers, why do writers and bloggers bother making their views public if they lack the courage or the means to stand by their words? This applies especially to writers and bloggers who express anti-liberal, anti-leftist, and Christian views in their work. Perhaps I am being too harsh with this criticism and perhaps it is not my place to judge, but I believe this refusal to identify with these expressed ideas essentially reveals an immense failure of character and moral courage.

Put simply, those who rail against the evils of our modern world and make attempts to offer hope and guidance but refuse to put their names to their ideas are cowards. In my mind, their reluctance to stand by their words points to excessive self-concern, one that overrides the good they are saying or doing.

Of course, to write under one’s real name or an assumed name is a matter of personal choice. I am willing to accept that some writers believe it is the right thing to do, but this belief does not necessarily entail that writing pseudonymously is the right thing to do.

On the contrary, I am certain it is the wrong thing to do.

Having said that, reading blogs is also a matter of personal choice. Though I appreciate the fine work pseudonymous bloggers often offer, I can no longer support their decision to hide behind fictitious names. Thus, I have made the personal choice to avoid blogs with pseudonymous authorship going forward.

I don’t care to hear any more explanations, rationalizations, or justifications concerning the use of false names.

For me, the matter is simple:

Writers who are afraid to be Real should not be writing about Reality.

Note: This criticism is aimed chiefly at bloggers, writers, and thinkers, and not at pseudonymous commenters. Nevertheless, pseudonymous commenters would also benefit from considering the negative implications of using fictitious names. If you cannot develop the fortitude to openly speak your truth now, when do you expect to develop it?

Published on May 06, 2019 12:23

May 4, 2019

On Becoming Aware One Has Crossed the Point of No Return

When I abandoned my secondary school teaching career in 2015, I made a silent vow to never go back to the vocation. A few months after I quit teaching, I expanded the vow to include most corporate/bureaucratic-type jobs regardless of the material benefits these often bring.

Human resources departments in our contemporary world invest a great deal of time and effort investigating the backgrounds of their prospective employees, and I imagine even a cursory glance this blog or my fiction writing would be enough for most corporations and bureaucracies to render me persona-non-grata. Hence, I have come to the realization that I have likely disqualified myself from most corporate/bureaucratic-type work going forward.

For better or for worse, I have irrevocably committed myself to burning bridges over the past four years. I have crossed the Rubicon – passed the point of no return. The die has been cast.

I know I cannot go back, even if I wanted to.

Oddly enough, this knowledge helps me sleep better at night.

Human resources departments in our contemporary world invest a great deal of time and effort investigating the backgrounds of their prospective employees, and I imagine even a cursory glance this blog or my fiction writing would be enough for most corporations and bureaucracies to render me persona-non-grata. Hence, I have come to the realization that I have likely disqualified myself from most corporate/bureaucratic-type work going forward.

For better or for worse, I have irrevocably committed myself to burning bridges over the past four years. I have crossed the Rubicon – passed the point of no return. The die has been cast.

I know I cannot go back, even if I wanted to.

Oddly enough, this knowledge helps me sleep better at night.

Published on May 04, 2019 20:54

No More Faustian Grandeur

Everything in the material world has a price. In general, gaining or acquiring a thing in the material world happens through an exchange mechanism. One material thing can be exchanged for another material thing of relatively equal value. Money, labor, favors, property, connections, and time are among the most common material currencies. In theory, one should be able to acquire almost any material thing with one or any combination of these currencies, and in some rare cases, one still can.

Yet it is becoming increasingly difficult to acquire material things with material currencies alone. More is required. Although money, labor, favors, property, connections, and time are all still valid and valuable currencies in the physical world, they pale in comparison to the most valuable currency of all – spirit.

The lords who walk secretly among us have little interest in accumulating more of the material. They own almost all of it already. For them, the material is investment capital - a means to an end. The lords are playing for legacy. They employ end game tactics and winner-take-all strategies.

In earlier eras, they offered vast sums of the physical in exchange for the metaphysical, but times have changed. The lords have convinced modern people that the immaterial truly is immaterial. At the same time, they have also worked diligently to mold world mechanisms into an intricate and complex system of industrial-scale damnation.

The results thus far?

In our contemporary world, even the most trivial of material transactions requires the expense of spirit. Consider it a testament to the system’s conveyor belt efficiency and assembly line effectiveness, which have not only succeeded in ramping up the destruction, but have also efficaciously stripped the transactions of all their former Faustian drama and grandeur.

Yet it is becoming increasingly difficult to acquire material things with material currencies alone. More is required. Although money, labor, favors, property, connections, and time are all still valid and valuable currencies in the physical world, they pale in comparison to the most valuable currency of all – spirit.

The lords who walk secretly among us have little interest in accumulating more of the material. They own almost all of it already. For them, the material is investment capital - a means to an end. The lords are playing for legacy. They employ end game tactics and winner-take-all strategies.

In earlier eras, they offered vast sums of the physical in exchange for the metaphysical, but times have changed. The lords have convinced modern people that the immaterial truly is immaterial. At the same time, they have also worked diligently to mold world mechanisms into an intricate and complex system of industrial-scale damnation.

The results thus far?

In our contemporary world, even the most trivial of material transactions requires the expense of spirit. Consider it a testament to the system’s conveyor belt efficiency and assembly line effectiveness, which have not only succeeded in ramping up the destruction, but have also efficaciously stripped the transactions of all their former Faustian drama and grandeur.

Published on May 04, 2019 09:53

May 3, 2019

Beyond Term Goals

Both short term goals and long term goals are irrelevant if beyond term goals are never considered.

Published on May 03, 2019 03:29

May 2, 2019

The Fallen Man

I stumbled across a newspaper clipping of my first published short story the other day and thought it would be fun to share it. Though I have made a few minor corrections, the story as it appears here as it did when it was published in the Toronto Star back in 1992. I was twenty-one when I wrote this story, so read with mercy.

I am not sure how I feel about this story today. Having said that, I believe it still possesses a certain charm.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The Fallen Man

The man fell from the sky on a cloudy spring morning in 1942.

I was standing by my mother’s side as she tended to the geraniums and crocuses in the garden. I looked up at the sky, wishing I could float up from the gentle rolling hills of the Yorkshire Moors and form a union with the grey expanse above me. I was six-years-old then, and I wanted nothing more than to be sky.

That was when I saw him, falling almost directly above us, tangled in the cords and material of his parachute. Watching this unexpected reverie, I could think only of the story my older brother, Thomas, read to me in the evenings in the parlour. The story of a boy named Icarus who soared through the sky with feather-and-wax wings. Through the tingle of awe and confusion, I could think of nothing else. I anxiously tugged my mother’s apron and pointed to the sky above us.

“My God,” she whispered upon spotting the falling man.

He landed beside the barn just a short distance from where we stood. I released my mother’s apron and ran to the man as his parachute fluttered to the ground.

"Emma! Emma! Come back!"

I heard my mother calling to me, but I did not listen – I had to get a closer look at the fallen man.

He lay on his back in the deep mud. He was wearing the same kinds of clothes the men in the nearby village wore. I wanted to ask him what it was like to be sky, but his eyes were closed and he appeared to be sleeping. I walked around his motionless body, searching the mud for his wings. Mother knelt down beside him, muddying her apron as she did so. She touched his neck with her long, slender fingers.

“I can’t find his wings,” I said.

My mother paid no attention to me and called for my older brother. A moment later, Thomas emerged from the barn. Upon seeing the fallen man, his face twisted into a deep frown and his fingers curled into white-knuckled fists.

“Help me carry him to the house, Tom,” mother said.

Thomas remained where he stood for a long time, staring at my mother kneeling beside the man. Finally, he trudged into the mud and helped carry the man into the house. With considerable difficulty, they took him into my parents’ room on the second floor and placed him on the bed. Thomas’s face went red and his eyes became narrow slits.

“We need to inform the authorities immediately,” he grumbled.

“We’ll discuss it later,” mother said quietly.

“What is there to discuss? He’s a spy.”

“Later, Tom.”

Thomas stomped out of the room mumbling something I could not make out.

I stood by mother’s side as she tended to the man’s injuries. I wanted very much to speak to him and ask him if he knew Icarus, but his eyes remained closed. I contented myself by simply looking at him. He had a square face and cinnamon hair. Thomas had called him a spy. I did not know what kind of spy the man was or what his being a spy could have to do with him falling from the sky.

“Is he a spy, mum?” I asked mother as she wiped mud from the man’s face.

She paused and nodded her head tensely. “Yes. I’m afraid he very well could be.”

“Why did he fall from the sky?”

“I’m not certain. It has to do with the war.”

“He’s part of the war? Like father is?”

“Yes. I suppose so.”

I wanted to ask more questions, but mother put her finger to her lips, ushered me out of the room, and closed the door behind me. I spent the rest of the day thumbing through the myth book and staring at the picture of Icarus falling into the sea after the sun had melted his wings. It was a sad picture. The farmer ploughing the field in the foreground was completely oblivious to the sea swallowing Icarus in the background. I thought the fallen man was fortunate to have landed on our farm in the countryside rather than in the sea.

Mother did not emerge from the room until it was time for dinner. I asked to see the fallen man, but she would have none of it. Once mother had prepared dinner, she called Tom who had spent the entire day outside even though he usually finished his chores by noon. We sat down and ate quietly. Dinner was strange that evening. We sat at the table like strangers.

“We should tell the authorities,” Thomas said finally, puncturing the silence. Mother did not reply. She continued eating, keeping her gaze firmly fixed on the plate before her. I noticed her hands were trembling as she held her knife and fork. “He’s a German, mum! They caught one just like him three weeks ago near York. A spy, that’s what that one was. And that’s what this is one, too!”

“He regained consciousness a few hours ago,” mother said, her voice barely above a whisper. “He told me he wasn’t a spy. He said he was escaping from the war.”

Thomas scoffed. “In English, no doubt? What did you expect he would tell you? He’s the enemy. We’ll raise suspicions if we keep him here without informing the authorities. Others likely saw him fall. They’re probably looking for him now. And here you are playing nurse!”

“That’s enough, Tom!” mother shouted.

Thomas was taken aback. He snorted in disgust and dropped his fork onto his plate. The room fell silent again. I could not understand what had upset my brother so much.

“Mum said the fallen man and father are alike,” I said suddenly in an effort to ease the tension in the room.

“What?” Thomas cried. He stood up suddenly, knocking over his chair as he did so. “How could you say that?”

His shouting hurt my ears. I reached under my chair and grabbed the myth book as he continued ranting at my mother. “I think the man is like this,” I said showing him the picture of Icarus once I had found it in the book. Thomas snatched the book from my hands and dropped it on the floor.

“You know nothing, Emma” he sneered.

“Think of your dad, Tom,” mother said quietly. “What if he were injured and needed help? I don’t want to hand him over if he truly is escaping.”

“This is absurd!” Thomas spat in anger. He walked toward the door. “I’m sleeping in the barn as long as he’s here!” He opened the door. “You’d better keep the bedroom locked,” he said ominously before slamming the door behind him. Mother stared at the table before her while I picked up the myth book and hugged it to my chest.

Mother took some food and water into the bedroom and returned a few minutes later to help me clear the table. We retired to the parlour after we had finished the washing up. She built a nice fire in the fireplace, which always made the room feel soft and warm, even softer and warmer than the chapel we went to on Sundays. Thomas remained outside. I wished he would come inside and read me the story of Icarus. Mother sat in her chair crocheting and listening to the war reports on the radio. I found the announcer’s voice irritating – it was like a droning machine; like the airplanes I occasionally heard flying overhead in the middle of the night.

“Why is Tom cross at you, mum?” I asked after mother had turned off the radio.

“Because I am helping the man,” she replied.

“But it’s good to help others, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but Thomas doesn’t think it’s a good idea to help this man,” my mother explained.

“Why?”

“It’s complicated, love,” my mother said gently.

She turned her dark eyes up from her needlework and looked at the photograph of father she kept on the fireplace mantle. My father was a handsome man, and the soldier’s uniform he wore in the photograph made him look even more handsome. I could barely remember my father. I was very little when he left for the war. Mother said he was in Africa. I looked at the photograph, trying to extract some form and feeling from the image, but the man who was my father remained little more to me than a faint, sepia-toned whisper of humanity encased behind a pane of glass.

To my surprise, I noticed my mother had begun to cry. Her dark eyes welled with tears, and she was mouthing words that made no sounds. I suddenly felt strangely out of place – as if my presence had become intrusive. I wanted to approach my mother and embrace her, but I didn’t. Instead, I tucked the myth book under my arm and left the room. The radio announcer’s voice came back on once I was in the hallway. I paused for a moment and noticed the droning, monotone voice had all but drowned out my mother’s soft sobs.

My thoughts drifted to the fallen man. Even though my mother had strictly forbidden me to even consider it, I crept up the stairs to my parents’ room. I could see a thin sliver of light at the bottom of the door. Holding my breath, I turned the doorknob and quietly entered the room. Mother had left a couple of candles burning in the room, and the flickering flames cast a myriad of magical shadows on the walls and ceiling. The fallen man lay in bed, and he watched me step into the room, his eyes wide with a strange blend of curiosity and fear. The look on my face must have reflected something similar. We stared at each other wordlessly for a minute or two before I finally worked up the courage to walk toward the bed. Clutching the myth book firmly in my arms, I stopped by the side of the bed.

“Did you fly too close to the sun?” I asked. The fallen man looked at my blankly. His eyes were deep blue, like the sky on clear days. “Is that why you fell? Because you flew too close to the sun?”

He winced as he attempted to make sense of my words.

“Mother thinks you might be like father, but Thomas doesn’t think so,” I continued. It was then that I noticed the swelling around his ankle, which had turned a deep shade of plum purple. I pointed to another photograph of my father on the nightstand, this one taken on my parents’ wedding day.

“Is that your father?” the man asked quietly. He spoke English well, but he pronounced the words in an odd way.

“Yes. He left for the war and is in Africa now,” I said. Though I still felt a little anxious in his presence, the man seemed gentle and kind. I opened the myth book to the picture of Icarus and handed the book to the fallen man. “Did you fly too close to the sun, too?” I asked pointing at the picture in the myth book. “Icarus was trying to escape an island with his father, but he flew too close to the sun and his wings melted. Is that what happened to you?”

At first, the man did not seem to understand what I was saying, but as he studied the picture before him, a tender smile slowly spread across his face, and he nodded his head in agreement. “Yes,” he said after some time had passed. “Yes. I am like him. I flew too close to the sun.”

“Will you go back to the sky when you are well? If you do, can you take me with you? I like the sky and would love to see it up close,” I said quickly. When I finished speaking, I heard something behind us and turned to see my mother standing in the doorway.

“Come along, Emma,” she said, her voice noticeably nervous.

“You can keep the book,” I said. I left the myth book in the fallen man’s hands and walked back toward the doorway.

“I’m locking the door for the night,” my mother told the man firmly. “Do you need anything before I do?”

The man’s expression turned serious. He shook his head and then said, “What will you do with me?”

Mother opened her mouth to speak, but in the end said nothing. She closed the door and locked it from the outside. Mother put me to bed soon after that. Before I fell asleep, I had visions of flying through the sky, around puffy cotton clouds high above the sea.

Knocking and shouting. The sharp sounds of knocking and shouting woke me. It was still dark outside. An invisible rain faintly pattered against the windowpanes. The knocking and shouting were coming from downstairs. I scrambled out of my bed and down the staircase. Mother was standing in the parlour stone-faced. Thomas and six men in soldier uniforms stood in the room before her.

“Upstairs. First door on the left,” Thomas said to the oldest soldier. He then glared at my mother who kept her eyes fixed on the photograph of my father. “It’s the right thing, mum. You know it is.”

The soldiers marched up the stairs clutching their rifles. Thomas and I ran after them. The soldiers paused before the bedroom door. The oldest soldier held a pistol in his right hand. With his left hand, he turned the key my mother had left in the lock.

“Be ready for anything, lads,” the oldest soldier said. He then threw the door open and allowed the other soldiers to rush inside. I was worried the soldiers wanted to hurt the fallen man or take him away before he could return to the sky, but a sudden hush settled over the house after the soldiers burst into the room. I peered inside to see what was happening. Save for the soldiers, the room was empty. The fallen man was not in the bed. The soldiers searched the room, but they did not find the fallen man. The oldest soldier stopped before the open window and took out his electric torch.

“He must have heard us coming,” he said quickly. “Outside, lads.”

“He couldn’t have made it far,” Thomas said to the oldest soldier.

The soldiers filed out of the room and down the stairs. A moment later, yellow beams of light from the soldiers’ electric torches pierced the darkness outside. Thomas remained in the room with me, staring at the open window in disbelief. I saw the myth book on the nightstand and moved to retrieve it. As I did so, I noticed something on the bed. There, nestled in the sheets, lay two small wings crafted from candle wax, twine, and feathers. I gingerly picked the wings up and displayed them to my brother.

“He’s not a fallen man, anymore,” I said.

Thomas grunted and walked out of the room leaving me alone, my head flooded with visions of Icarus rising up from the sea and soaring back up into the azure depths of the sky.

I am not sure how I feel about this story today. Having said that, I believe it still possesses a certain charm.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The Fallen Man

The man fell from the sky on a cloudy spring morning in 1942.

I was standing by my mother’s side as she tended to the geraniums and crocuses in the garden. I looked up at the sky, wishing I could float up from the gentle rolling hills of the Yorkshire Moors and form a union with the grey expanse above me. I was six-years-old then, and I wanted nothing more than to be sky.

That was when I saw him, falling almost directly above us, tangled in the cords and material of his parachute. Watching this unexpected reverie, I could think only of the story my older brother, Thomas, read to me in the evenings in the parlour. The story of a boy named Icarus who soared through the sky with feather-and-wax wings. Through the tingle of awe and confusion, I could think of nothing else. I anxiously tugged my mother’s apron and pointed to the sky above us.

“My God,” she whispered upon spotting the falling man.

He landed beside the barn just a short distance from where we stood. I released my mother’s apron and ran to the man as his parachute fluttered to the ground.

"Emma! Emma! Come back!"

I heard my mother calling to me, but I did not listen – I had to get a closer look at the fallen man.

He lay on his back in the deep mud. He was wearing the same kinds of clothes the men in the nearby village wore. I wanted to ask him what it was like to be sky, but his eyes were closed and he appeared to be sleeping. I walked around his motionless body, searching the mud for his wings. Mother knelt down beside him, muddying her apron as she did so. She touched his neck with her long, slender fingers.

“I can’t find his wings,” I said.

My mother paid no attention to me and called for my older brother. A moment later, Thomas emerged from the barn. Upon seeing the fallen man, his face twisted into a deep frown and his fingers curled into white-knuckled fists.

“Help me carry him to the house, Tom,” mother said.

Thomas remained where he stood for a long time, staring at my mother kneeling beside the man. Finally, he trudged into the mud and helped carry the man into the house. With considerable difficulty, they took him into my parents’ room on the second floor and placed him on the bed. Thomas’s face went red and his eyes became narrow slits.

“We need to inform the authorities immediately,” he grumbled.

“We’ll discuss it later,” mother said quietly.

“What is there to discuss? He’s a spy.”

“Later, Tom.”

Thomas stomped out of the room mumbling something I could not make out.

I stood by mother’s side as she tended to the man’s injuries. I wanted very much to speak to him and ask him if he knew Icarus, but his eyes remained closed. I contented myself by simply looking at him. He had a square face and cinnamon hair. Thomas had called him a spy. I did not know what kind of spy the man was or what his being a spy could have to do with him falling from the sky.

“Is he a spy, mum?” I asked mother as she wiped mud from the man’s face.

She paused and nodded her head tensely. “Yes. I’m afraid he very well could be.”

“Why did he fall from the sky?”

“I’m not certain. It has to do with the war.”

“He’s part of the war? Like father is?”

“Yes. I suppose so.”

I wanted to ask more questions, but mother put her finger to her lips, ushered me out of the room, and closed the door behind me. I spent the rest of the day thumbing through the myth book and staring at the picture of Icarus falling into the sea after the sun had melted his wings. It was a sad picture. The farmer ploughing the field in the foreground was completely oblivious to the sea swallowing Icarus in the background. I thought the fallen man was fortunate to have landed on our farm in the countryside rather than in the sea.

Mother did not emerge from the room until it was time for dinner. I asked to see the fallen man, but she would have none of it. Once mother had prepared dinner, she called Tom who had spent the entire day outside even though he usually finished his chores by noon. We sat down and ate quietly. Dinner was strange that evening. We sat at the table like strangers.

“We should tell the authorities,” Thomas said finally, puncturing the silence. Mother did not reply. She continued eating, keeping her gaze firmly fixed on the plate before her. I noticed her hands were trembling as she held her knife and fork. “He’s a German, mum! They caught one just like him three weeks ago near York. A spy, that’s what that one was. And that’s what this is one, too!”

“He regained consciousness a few hours ago,” mother said, her voice barely above a whisper. “He told me he wasn’t a spy. He said he was escaping from the war.”

Thomas scoffed. “In English, no doubt? What did you expect he would tell you? He’s the enemy. We’ll raise suspicions if we keep him here without informing the authorities. Others likely saw him fall. They’re probably looking for him now. And here you are playing nurse!”

“That’s enough, Tom!” mother shouted.

Thomas was taken aback. He snorted in disgust and dropped his fork onto his plate. The room fell silent again. I could not understand what had upset my brother so much.

“Mum said the fallen man and father are alike,” I said suddenly in an effort to ease the tension in the room.

“What?” Thomas cried. He stood up suddenly, knocking over his chair as he did so. “How could you say that?”

His shouting hurt my ears. I reached under my chair and grabbed the myth book as he continued ranting at my mother. “I think the man is like this,” I said showing him the picture of Icarus once I had found it in the book. Thomas snatched the book from my hands and dropped it on the floor.

“You know nothing, Emma” he sneered.

“Think of your dad, Tom,” mother said quietly. “What if he were injured and needed help? I don’t want to hand him over if he truly is escaping.”

“This is absurd!” Thomas spat in anger. He walked toward the door. “I’m sleeping in the barn as long as he’s here!” He opened the door. “You’d better keep the bedroom locked,” he said ominously before slamming the door behind him. Mother stared at the table before her while I picked up the myth book and hugged it to my chest.

Mother took some food and water into the bedroom and returned a few minutes later to help me clear the table. We retired to the parlour after we had finished the washing up. She built a nice fire in the fireplace, which always made the room feel soft and warm, even softer and warmer than the chapel we went to on Sundays. Thomas remained outside. I wished he would come inside and read me the story of Icarus. Mother sat in her chair crocheting and listening to the war reports on the radio. I found the announcer’s voice irritating – it was like a droning machine; like the airplanes I occasionally heard flying overhead in the middle of the night.

“Why is Tom cross at you, mum?” I asked after mother had turned off the radio.

“Because I am helping the man,” she replied.

“But it’s good to help others, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but Thomas doesn’t think it’s a good idea to help this man,” my mother explained.

“Why?”

“It’s complicated, love,” my mother said gently.

She turned her dark eyes up from her needlework and looked at the photograph of father she kept on the fireplace mantle. My father was a handsome man, and the soldier’s uniform he wore in the photograph made him look even more handsome. I could barely remember my father. I was very little when he left for the war. Mother said he was in Africa. I looked at the photograph, trying to extract some form and feeling from the image, but the man who was my father remained little more to me than a faint, sepia-toned whisper of humanity encased behind a pane of glass.

To my surprise, I noticed my mother had begun to cry. Her dark eyes welled with tears, and she was mouthing words that made no sounds. I suddenly felt strangely out of place – as if my presence had become intrusive. I wanted to approach my mother and embrace her, but I didn’t. Instead, I tucked the myth book under my arm and left the room. The radio announcer’s voice came back on once I was in the hallway. I paused for a moment and noticed the droning, monotone voice had all but drowned out my mother’s soft sobs.

My thoughts drifted to the fallen man. Even though my mother had strictly forbidden me to even consider it, I crept up the stairs to my parents’ room. I could see a thin sliver of light at the bottom of the door. Holding my breath, I turned the doorknob and quietly entered the room. Mother had left a couple of candles burning in the room, and the flickering flames cast a myriad of magical shadows on the walls and ceiling. The fallen man lay in bed, and he watched me step into the room, his eyes wide with a strange blend of curiosity and fear. The look on my face must have reflected something similar. We stared at each other wordlessly for a minute or two before I finally worked up the courage to walk toward the bed. Clutching the myth book firmly in my arms, I stopped by the side of the bed.

“Did you fly too close to the sun?” I asked. The fallen man looked at my blankly. His eyes were deep blue, like the sky on clear days. “Is that why you fell? Because you flew too close to the sun?”

He winced as he attempted to make sense of my words.

“Mother thinks you might be like father, but Thomas doesn’t think so,” I continued. It was then that I noticed the swelling around his ankle, which had turned a deep shade of plum purple. I pointed to another photograph of my father on the nightstand, this one taken on my parents’ wedding day.

“Is that your father?” the man asked quietly. He spoke English well, but he pronounced the words in an odd way.

“Yes. He left for the war and is in Africa now,” I said. Though I still felt a little anxious in his presence, the man seemed gentle and kind. I opened the myth book to the picture of Icarus and handed the book to the fallen man. “Did you fly too close to the sun, too?” I asked pointing at the picture in the myth book. “Icarus was trying to escape an island with his father, but he flew too close to the sun and his wings melted. Is that what happened to you?”

At first, the man did not seem to understand what I was saying, but as he studied the picture before him, a tender smile slowly spread across his face, and he nodded his head in agreement. “Yes,” he said after some time had passed. “Yes. I am like him. I flew too close to the sun.”

“Will you go back to the sky when you are well? If you do, can you take me with you? I like the sky and would love to see it up close,” I said quickly. When I finished speaking, I heard something behind us and turned to see my mother standing in the doorway.

“Come along, Emma,” she said, her voice noticeably nervous.

“You can keep the book,” I said. I left the myth book in the fallen man’s hands and walked back toward the doorway.

“I’m locking the door for the night,” my mother told the man firmly. “Do you need anything before I do?”

The man’s expression turned serious. He shook his head and then said, “What will you do with me?”

Mother opened her mouth to speak, but in the end said nothing. She closed the door and locked it from the outside. Mother put me to bed soon after that. Before I fell asleep, I had visions of flying through the sky, around puffy cotton clouds high above the sea.

Knocking and shouting. The sharp sounds of knocking and shouting woke me. It was still dark outside. An invisible rain faintly pattered against the windowpanes. The knocking and shouting were coming from downstairs. I scrambled out of my bed and down the staircase. Mother was standing in the parlour stone-faced. Thomas and six men in soldier uniforms stood in the room before her.

“Upstairs. First door on the left,” Thomas said to the oldest soldier. He then glared at my mother who kept her eyes fixed on the photograph of my father. “It’s the right thing, mum. You know it is.”

The soldiers marched up the stairs clutching their rifles. Thomas and I ran after them. The soldiers paused before the bedroom door. The oldest soldier held a pistol in his right hand. With his left hand, he turned the key my mother had left in the lock.

“Be ready for anything, lads,” the oldest soldier said. He then threw the door open and allowed the other soldiers to rush inside. I was worried the soldiers wanted to hurt the fallen man or take him away before he could return to the sky, but a sudden hush settled over the house after the soldiers burst into the room. I peered inside to see what was happening. Save for the soldiers, the room was empty. The fallen man was not in the bed. The soldiers searched the room, but they did not find the fallen man. The oldest soldier stopped before the open window and took out his electric torch.

“He must have heard us coming,” he said quickly. “Outside, lads.”

“He couldn’t have made it far,” Thomas said to the oldest soldier.

The soldiers filed out of the room and down the stairs. A moment later, yellow beams of light from the soldiers’ electric torches pierced the darkness outside. Thomas remained in the room with me, staring at the open window in disbelief. I saw the myth book on the nightstand and moved to retrieve it. As I did so, I noticed something on the bed. There, nestled in the sheets, lay two small wings crafted from candle wax, twine, and feathers. I gingerly picked the wings up and displayed them to my brother.

“He’s not a fallen man, anymore,” I said.

Thomas grunted and walked out of the room leaving me alone, my head flooded with visions of Icarus rising up from the sea and soaring back up into the azure depths of the sky.

Published on May 02, 2019 04:08

May 1, 2019

A Confession of Spiritual Capitulation

"How sublime! Perhaps there is hope for humanity after all! I admire all of you. You are stronger than I. You beat me.” Verge turned back to Béla. “I used to be like you – ambitious, energetic, idealistic. Head full of noble artistic ambitions. If only I were a man of stronger convictions, of firmer discipline, but I am a weak man, a man crushed by temptation, moved only by simple pleasures and little indulgences. I do not have the fortitude to resist their traps. I do not have the endurance to last the race. I chose the easy way. I accept my shortcomings and have learned to live with them, but I am always touched when I meet people of a higher caliber who are able to proceed where I failed. Of course, I meet fewer and fewer higher caliber people as my life drags on.”

A tinge of sadness touched Anthony Vergil’s bearded face and it seemed as if part of him had drifted away to some faraway place. The trance lasted barely a moment. The sadness faded as quickly as it had appeared and he smiled, raised his snifter again, and said, “I tip my hat to both of you, gentlemen.”

-excerpted from The City of Earthly Desire

A tinge of sadness touched Anthony Vergil’s bearded face and it seemed as if part of him had drifted away to some faraway place. The trance lasted barely a moment. The sadness faded as quickly as it had appeared and he smiled, raised his snifter again, and said, “I tip my hat to both of you, gentlemen.”

-excerpted from The City of Earthly Desire

Published on May 01, 2019 03:33

April 30, 2019

The Wandering Baron's Quality of Light

Light at Dawn - 1890 At the age of thirteen or fourteen, I briefly entertained notions of becoming a painter, but my utter lack of talent and skill quickly put those notions to rest. One thing I could never master when I dabbled around with painting as a teenager was light. Try as I might, I was utterly unsuccessful at bringing any realistic or even impressionistic sense of light to anything I attempted. It did not take me long to realize that evoking light in painting was no small feat.

Light at Dawn - 1890 At the age of thirteen or fourteen, I briefly entertained notions of becoming a painter, but my utter lack of talent and skill quickly put those notions to rest. One thing I could never master when I dabbled around with painting as a teenager was light. Try as I might, I was utterly unsuccessful at bringing any realistic or even impressionistic sense of light to anything I attempted. It did not take me long to realize that evoking light in painting was no small feat.One painter who, in my mind, succeeded in bringing a sublime quality of light to his paintings was the Hungarian painter László Mednyansky - (1852 - 1919).

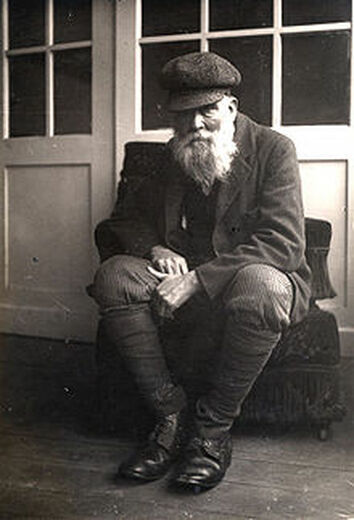

A curious personage in Hungarian art history, Mednyansky hailed from an aristocratic family based in what is today a part of Slovakia. Despite his background, Mednyansky spent the majority of his life traveling around Europe and working as artist. Surprisingly, he socialized with any and every class of people he encountered on his meanderings and spent long stretches living a solitary and somewhat secluded life. While viewing some of his works online, I came across a reference that claims he was occasionally referred to as "The Wandering Baron."

A curious personage in Hungarian art history, Mednyansky hailed from an aristocratic family based in what is today a part of Slovakia. Despite his background, Mednyansky spent the majority of his life traveling around Europe and working as artist. Surprisingly, he socialized with any and every class of people he encountered on his meanderings and spent long stretches living a solitary and somewhat secluded life. While viewing some of his works online, I came across a reference that claims he was occasionally referred to as "The Wandering Baron."Sadly, I do not know much more about Laszló Medyansky at the moment, but I hope to learn more about him and his art this summer when I will hopefully have more free time to indulge in such pursuits. In the meantime, I invite you to view some of his works. The paintings I have included in the selection below exemplify Mednyansky's masterful ability to bring light onto a canvas. The sublimity with which he depicts light raises it to the level of the subject matter itself; in some cases, the light overpowers the landscapes and dominates the canvas to the point of transcendence. Truly splendorous stuff, in my humble opinion.

Published on April 30, 2019 02:35

April 28, 2019

The Freedom of Choice

You are always free to choose the right thing. The right thought. The right action. That is the only real freedom you possess. It is always simple, but often challenging.

The wrong thing is never simple, but usually easy. When you give in to the wrong thing, it comes from wrong thought and leads to wrong action. The wrong thing is not an exercise in freedom.

There is no choice; only submission.

When you submit to the wrong thing, freedom dissolves and drips through your fingers like melting gold.

You are left with nothing of value. The surrender brands you, and the slavery to which you have submitted shall mark you as one who failed to be free.

The wrong thing is never simple, but usually easy. When you give in to the wrong thing, it comes from wrong thought and leads to wrong action. The wrong thing is not an exercise in freedom.

There is no choice; only submission.

When you submit to the wrong thing, freedom dissolves and drips through your fingers like melting gold.

You are left with nothing of value. The surrender brands you, and the slavery to which you have submitted shall mark you as one who failed to be free.

Published on April 28, 2019 12:00

April 26, 2019

Peterson Not a Sell Out?

A few weeks ago a commenter on this blog criticized my dismissal of Jordan Peterson as a sell out by claiming I would do the exact same thing Peterson is doing if I were offered the same chance at success Peterson is currently enjoying.

A few weeks ago a commenter on this blog criticized my dismissal of Jordan Peterson as a sell out by claiming I would do the exact same thing Peterson is doing if I were offered the same chance at success Peterson is currently enjoying.I politely informed the commenter that, as dishonest as it would likely sound to him, I would be unwilling and unable to make many of the compromises Peterson has made over the past year or two. The worldly-wise commenter in question scoffed at this reply and launched a three paragraph tirade in which he attacked my insincerity and naivety.

The response did not bother me much; I have learned comments on blogs can be quite idiosyncratic - they tend to reveal much more about the commenter making the comment than they do anything else.

In any case, the purpose of this post is not to harangue that specific commenter, but to dispel, once and for all, any lingering doubts anyone else might still harbor concerning Jordan B Peterson. Contrary to popular belief, the man is an absolute sell-out who does what he does solely for his own good rather than for the Good.

If you do not see that after reading this post, you will never see it, and I will make no further attempts to convince you. However, if you see nothing inherently wrong with Peterson's cashing in at every conceivable turn, I humbly suggest you re-examine your own assumptions and general worldview because some major adjustments need to be made.

Regardless, I invite those who may still be sitting on the fence about JP to visit his official merchandise site where they can happily peruse a fine selection of Peterson products including ties, mugs, leggings, t-shirts, and blankets among other items. Yes, for a mere 14 euros (!), you too can be the proud owner of a pair of Jordan Peterson lobster socks.

Rumor has it Peterson has other great merchandise in the works including lobster-scented cologne and an entire range of dominance hierarchy-inspired sex toys, so make sure to check back and check back often so you don't miss out on all that great stuff!

Lobster socks.

Come at me again about how the greatest intellectual in the Western world is no sell out.

Published on April 26, 2019 22:09