Larry Brooks's Blog, page 51

May 30, 2011

Deconstructing "The Help"

My opinion: with all the workshops… all the how-to books… all the blogs…

… with all that to help us, I think the most illuminating, clarifying and empowering thing writers can do is to read or see – and then analyze – stories (books and movies) in all genres with a view toward seeing what makes them tick.

Med students have cadavers, we have bestsellers and great films.

We have "The Help." A story that is still very much alive and kicking.

Dead or alive, there is much to learn in the transitory space – also known as a slippery slope – between theory and reality.

What "The Help" can teach us.

"The Help" is a study in place, setting and character.

None of which, by the way, either compete with or compromise the unfolding dramatic tension across a textbook-perfect four-part story arc – structure – punctuated by specific, easily identified narrative milestones. There are many scenes that, while remaining mission-driven, seem to drop us into a moment in time in which character dynamics are exposed, seemingly without much forward-moving plot exposition.

But don't be fooled. Or lulled into complacency. Because sub-text is raging on every page.

"The Help" is nothing if not all about sub-text.

A reader of thrillers might get impatient with this aspect of "The Help," but it is there by design. Why? Because the weight of our relationship with these characters, which is driven by our vicarious witnessing of their dynamics and inner responses, is the key to the entire novel.

What happens in the story is driven by what the characters are feeling, where more often it is the other way around.

The author understood this subtlety fully, most likely before she wrote a word. The story could have become lost in a sea of characterized vignettes, but there is always a sense that this is leading somewhere, and wherever it's headed is fraught with risk and stakes worth, perhaps, dying for.

For me, this is the essence of character-driven storytelling, while still delivering a story that is, purely in a dramatic sense, rich with tension and sub-text. We keep reading as much to find out what happens as anything else, and yet we wouldn't care about what happens had Stockett not delivered such a rich tableau of character and culture and the pulse of a time and place so effectively.

That's always a delicate balance, one that Stockett executes perfectly.

A Window Into Theme

To put it another way, "The Help" is a blending of craft and art in a way that is rare. And like Dan Brown's "The DaVinci Code," the core competency (element) that propelled it into the hearts and minds of critics and readers alike, with a resultant long term lease on the #1 spot on virtually every bestseller list out there, is it's theme.

That's the other first-tier level of learning and awareness that awaits us in this book. A similar story without the strong undercurrent of racial consequences, both on a micro/character level, and on a macro/societal level, probably wouldn't have resonated as it did.

The theme is what makes this story important, as well as rewarding on many levels. The book shows us how vital importance is to the success of the story.

If you haven't read "The Help" yet, I strongly recommend that you do, and that you join us in a major leap up the learning curve via an in-depth understanding of why this story works so well.

Because it's a duplicable, transferrable skill set.

No matter what genre you write in, a great story in any genre has something to teach us.

To show us, rather than simply tell us.

The latter part is my job. The former… I'll turn that over to Ms. Stockett for the next few posts.

Next Up: A Structural Summary of "The Help."

Until then, ask yourself this: how important is your story? What you are saying about history, life, humanity or culture that is important? And how does this show up as sub-text within your story?

Even if your story is all about entertainment, it'll fare better if there's at least a seed of importance – usually at the thematic level – somewhere in your pages.

Click HERE to learn more about the Six Core Competencies of successful storytelling.

Deconstructing "The Help" is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 25, 2011

The Flip Side of "Concept"

However you define it, "concept" is one of the Six Core Competencies of successful storytelling. It is an essence of storytelling that becomes a powerful tool in that development process, as described ad nauseum here on Storyfix. And in my new book.

And since we're about to deconstruct "The Help" over the next few weeks, the book becomes a great example of what this is about today.

This post isn't about Stockett's concept for "The Help." That'll be a big part of that series, as the book allows us to separate concept, theme and idea and premise in a clear and empowering way.

Rather, today's post is about how concept, as a generic, universally-applied core competency – as a tool – breaks down into two available realms: the creative and the mechanical.

"The Help" is a convenient and timely example of both.

The Creative Realm of Concept

At its most obvious, concept refers to the inherent proposition and invitation of the story on a narrative level. It suggests that if you create a set of characters, then concoct a compelling situation, then smush the two together, literary hi-jinks will ensue.

And that without the smush, something is lacking.

A great concept is the stuff of thrills, chills, drama, tension, laughter, wonder, turn ons, emotions and life lessons that turn good books into great books. Because, at its core, it is concept that gives great characters a stage upon which to show their stuff, which is the seed from which theme emerges.

When we think of concept, this is what we probably go to. A "what if?" proposition. The hook, that stage, the compelling notion of the fiction that is the source of dramatic tension, character arc and the prospect of engaging a reader's emotions.

But that creative view may not be enough to fully seize the conceptual moment at hand.

Because there is another realm – another opportunity – that is by definition totally conceptual in nature and execution. And if you don't address it and optimize it (make the best possible choices in this realm), it will leave the station without you and both define and restrict your story in doing so.

The Mechanical View of Concept

As described above, concept deals with what the story could and should be in a dramatic sense.

The mechanical take on concept deals with how the story should best be told.

This mechanical side of concept is comprised of the choices an author makes about voice, tense, time sequencing, narrative asides and other little tricks and structures that reside outside of the simply linear.

Sometimes – often, in fact – the simply linear is ideal.

But not always. When it isn't, you need a narrative concept (a mechanical concept) that does the job better.

As our first example, let's look at "The Help."

That story is told in first person. It was a choice, a decision – a concept – made at some early point in the story development process, as it is for any story. But Stockett didn't give in to the obvious choice, because there was a better choice on the table, one that wasn't obvious at all.

She uses not one, but three narrators, all of them delivered in first person. This, too, is conceptual, and by definition purely a mechanical one. Third person omniscient narrative could have been used, but that's a different concept.

The book is also written in present tense, much like a screenplay (fair warning: don't try this at home, it's very risky business).

Who knows how these mechanical decisions might have impacted the fact of the book. What we do know, however – based on results – is that Kathryn Stockett's choices worked.

I'm not talking about writing voice here (another of the six core competencies, one that is completely separate in context and execution), but rather, I'm labeling the means by which an author chooses to deliver a story – linear or otherwise – as conceptual.

Alice Sebold could, for example, have written "The Lovely Bones" as a musical. Same story exactly. Same hook, same conceptual underpinnings, same characters and drama. And if she did, that would have been a conceptual choice that would have defined the entire future of the story.

Or you could have written "A Chorus Line" as detective noir. After the fact we – the viewers – take these mechanical choices for granted. But staring at the blank page, taking them for granted can be fatal.

Or it can make your career.

Which is why this realm of mechanical conceptualization is so important.

Mechanical concepts become creative by means of their effectiveness.

Remember "Pulp Fiction"?

How it jumped around in time sequencing, showing us what actually took place near the end at various times in the sequence of the story. Nothing linear there. That's a concept, one residing in the mechanical realm of author decision-making.

Remember "The Bridges of Madison County?" A totally mechanical concept, in that the story unfolded in two spheres of time, with narrative bridging (no pun intended) them to optimize pace, tension and emotion.

Structure, while guided by principles, is very much a conceptual decision, because what goes where defines your story.

Did you see the film "500 Days of Summer"?

Each scene was labeled with graphic subtitles as one of those days, unfolding in what appeared to be a random order. Day 365, for example, occurs well before, say, Day 21.

But it wasn't remotely random from the author's seat. The story showed us what needed to be revealed in precisely the proper, optimized order, weaving backstory, false climaxes, abandoned hopes and rekindled passion together into a linear and artful love story that was more about how it arrived at its conclusion than the conclusion itself.

This, too, is a concept. A tricky one, since a story still needs to unfold in a thematically and dramatically linear fashion whatever mechanical choice the author makes.

In my 2004 novel, "Bait and Switch," I combined a first person protagonist narrative alternating with third person point-of-view chapters showing what was going on behind the curtain of the hero's awareness (once again sending a legion of old school writing teachers into a catatonic frenzy). According to the folks at Publishers Weekly that named it to the "Best Books of 2004" after a starred review, I'm thinking it worked.

A risky choice? Not really. I first saw that technique, by the way, in Nelson Demille's The Lion's Game (2002), and it blew my mind. A whole new world of conceptual possibility opened up simply by seeing it done, and done well.

The enlightened writer understands that these two conceptual landscapes– creative and mechanical – are on the table at all times. When seized early, even before a first draft, the storytelling is empowered and/or tested against a vision for it. If it's landed upon during the drafting process, that is an equally valid outcome of the story development process itself, because once that landing occurs, so does the vision for the story.

You can start a successful story without one, but you can't finish a successful story without a vision for it.

So along with asking ourselves, what would my hero do in this situation?, and, what will make the dramatic tension in this scene go vertical? (these among a long list of other conceptual questions)…

… we should also be asking ourselves what mechanical options – point of view, time sequencing, dialogue style and even how the thing looks on the page – best suit the story and our vision for it.

This is where risk, creativity and courage collide in a brilliant explosion of exhilarating potential.

This is the essence of optimization

Awareness is a beautiful thing.

Because in an avocation in which we can too easily begin to think that our stories are writing themselves… they aren't.

Rather, a story is like a child, tending to wander off to explore dangerous and wasted side trips and bad choices – one of which, I'll grant you, yield valuable lessons – and it's our job to shepherd them toward the sweet spot of dramatic optimization and literary bliss.

When that happens, know that both realms of conceptual decision making are in play… and that you have total control over the options presented by both.

The Flip Side of "Concept" is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 23, 2011

Getting Ready for "The Help"

Not long ago I announced that I'll be deconstructing the bestselling novel "The Help," by Kathryn Stockett, in a series of Storyfix posts. This is the first in that series.

If you don't recall my past deconstructions of novels and films (dive into the archives, there are a half dozen or so buried there), these are a great way to see and analyze all six core competencies of a successful story in action… especially structure.

Call it proof, call it transparency, call it enlightenment, call it the opening of a critical door of awareness. There's nothing like seeing a theory in full glorious action to bring it alive.

Many are excited and relieved to see the plot points right where they're supposed to be, doing what they're supposed to do, and the contextual missions of the four story parts unfolding in fully aligned, textbook glory.

Cynics, not so much. Because they must now look elsewhere to disprove the literary theory – which they tend to reject – and the validity behind all this story engineering stuff.

My hope is that this series turns a few cynics into enthusiasts for what is true… and as you'll see, proven.

I'm getting ready to launch the series in a week or so.

Until then, I wanted to share something that "The Help" shows us at the very highest levels of our understanding. A little morsel of clarity that is of primary value to readers who are also writers, much more so than the reading public in general.

A general reading public which, by the way, bought this book by the warehouse full.

Let's assume this means you.

"The Help" was Stockett's first novel, which adds to the utter shock and awe of its performance, both commercially and critically. It sports the usual litany of home run credentials: it was a #1 New York Times bestseller (for a year or so); all the other bestseller lists, too; it is currently #1 on the NY Times paperback list; and there's that inevitable major movie deal (the film comes out in August, you can see the preview on Youtube HERE… but you'll have to tolerate a 15 second commercial first).

Even better, virtually every reviewer praised the book for its power, its "pitch-perfect" delivery (a phrase used over and over, which speaks to the core competency of "writing voice"), its humor and its heart.

It defies genre, and in many ways qualifies as The Great American novel. Probably won't end up with that title, since it's about the worst and darkest part of our history and culture. That said, it's a historical novel that's about humanity more than history.

Not one critic praised the structure of the book, though many held the story up as iconic and important. Why? Because the structure is perfect. And when structure is perfect, nobody notices it because they're too busy swooning about the other five core competencies that it empowers.

That's a loaded sentence, which I encourage you to read again. Because it nails the relationship between structure and the rest of the things that will make a story successful. Nothing works without it.

It's like a perfectly tuned engine. You don't notice the engineering, you just appreciate the ride.

Here is the most exciting statistic of all.

Or, depressing. This is half-full-or-half-empty pop quiz moment.

"The Help" was rejected by 45 literary agents.

Read that again.

William Goldman, the sage Oscar winning screenwriter and novelist who said of the movie business – and is equally and obviously true of the publishing business – "nobody knows anything," is proven correct once again.

The First Lesson of "The Help"

You're gonna want to read this novel if you haven't already.

And if you have, get ready to want to read it again. Doing so – this or any other deconstructed story – in context to what should suddenly be clear, liberating and motivating in a way it isn't to someone who isn't an enlightened or open-minded writer, is the quickest route up the learning curve that I know.

This book is a clinic in mission-driven, perfect pitch, thematically devastating storytelling.

The story has three point-of-view narrators – right there it's already outside the box, with a generation of academic "creative writing" teachers rolling over in their graves – any one of which could be nominated as the protagonist.

But the more you read, the more you realize the hero of this story is Skeeter, a rich and not remotely spoiled young woman embarking on her career and life in general in 1962 Jackson, Mississippi. What career?

She desperately wants to be a writer.

Not a coincidence, I dare surmise.

In fact (and this is a lesson in concepting, which is one of the six core competencies), Skeeter's chosen profession is the driving catalyst of the entire story. Without it, "The Help" is nothing but a series of character profiles in a historical context.

Without that career choice, there is no story.

At first, like so many of us, Skeeter just wants to write.

She's not sure what or even why, and she'll take anything that requires a typewriter.

Which she soon does, writing household tips for a local daily for what amounts to nothing more than cigarette money (remember, this was 1962, when the belief systems of the day – also residing at the heart and soul of this story – ruled without question or surgeon general warnings).

Skeeter gets in touch with a Big Time Book Editor in New York, who barely gives her the time of day (that much hasn't changed since 1962, by the way). But she does manage to squeeze in some life-changing career advice, and Skeeter listens.

One wonders if Stockett herself lived this little Epiphany in her own writing journey. Could be the book began there, rather than some life-long burning desire to write about the civil rights movement. Or not. The two may have collided in an inspired moment of fate.

That's often what happens, too. Only Ms. Stockett knows.

Collisions between creative sparks and burning themes… that can be a very good thing.

That grouchy editor's advice was this: write something worth writing.

Something that hits people right where they live. That challenges. That upsets a farmers market full of apple carts. That lacks respect for the status quo. That makes the establishment uncomfortable. That rights wrongs and exposes truth.

That pisses people off… because it's so right.

Not hard to find a qualifying landscape for such a book in 1962 Mississippi, where virtually everything about that culture and the belief systems that defined it was in need of challenging.

I'm hoping you'll notice how that advice alters the course of Skeeter's life.

Not just her career, but her entire future, and the future of everyone in her sphere of influence and relationship.

As it did with both the protagonist and author of this novel, hearing this call for courage clearly can be the defining moment of your writing journey.

If you haven't read about the Six Core Competencies yet and would like to get more out of this series of deconstruction posts, click HERE.

Getting Ready for "The Help" is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 20, 2011

Weekend Writerly Wonderings, Wanderings and Wistful Whatevers

The Periodic Table of Storytelling

Remember science class? That poster next to the blackboard full of little squares containing letters that looked more like Scrabble than the foundation of all physical creation?

Me neither. But I do remember looking at that thing and asking… why?

Storyfix reader Eva Moon is sharing a link to a vast improvement on all things periodic-table-esque… a Periodic Table of Storytelling by a guy who calls himself the Computer Sherpa. It's an interactive interface with enough sub-topics about writing that, as he warns, might keep you busy for days.

You can buy the print if so moved (no, I'm not an affiliate, I just think it's cool).

Click HERE to check it out (click on the image for a larger version). Because we can never have enough interesting stuff on our walls.

One Reader's Home Run

Storyfix reader and contributor Chuck Hustmyre is a novelist. And he's living the dream many of us cling to: they've made a movie out of his novel, "House of the Rising Sun."

In case you didn't think an iUniverse title had a shot at such heights.

Check out the preview HERE. This is Big Time, even with no big stars. A little violent and sexual (isn't every good thriller?), so enter informed. Let's support Chuck and buy the book and then see his movie when it releases as a DVD this summer.

Something To Blow Your Advance On

I love Costco. Buy a lot of books there (obligatory relevance duly noted). Their stuff is supposed to be cheap.

How cheap is a 55-year old bottle of Scotch? How about twelve grand?

They also had a bottle of Cognac selling for $21,999, I kid you not.

That's a lot of Kindle ebooks at $2.99 each.

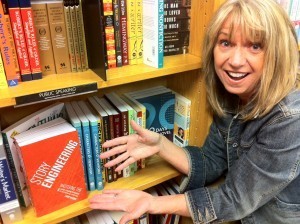

The Best Part of Being Published

Everybody does this when they get published: you go into bookstores, hunt down your book, and move the inventory to a better location.

Or, you can have your friends do it for you.

A friend of mine did that when my first novel, Darkness Bound, was published in 2000… as a paperback. With the best of intentions he moved the book to the bestseller rack, putting it in the #1 slot (that'd be upper left) ahead of Stephen King and Dean Koontz's new hardcovers.

It was, you see, a rack for hardcover bestsellers.

They had a shoot-on-sight poster of me near the door at Barnes & Noble for years.

Anyhow, it's still fun to see your book on a shelf, especially when friends send you pictures of it. This image is from my dear friend Renetta Krager, taken at a Borders in Portland, where I no longer live.

Write something amazing this weekend.

If not, do something amazing. Life is short. Live your story.

Weekend Writerly Wonderings, Wanderings and Wistful Whatevers is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 18, 2011

Part 2: A Deeper Understanding of Craft

Last post I opened a can of worms that a few of you found… confusing. Even discouraging.

And some of you, thankfully, found to be liberating and empowering.

I promised a follow-up, but did so without taking into consideration that confusion might ensue. So today's post is sort of a dance between clarification and continuation (sounds like marriage to me, but that's another post), with the goal of making room for all of us on the same page.

If you count yourself among the confused (rather than the discouraged, which is a different response altogether), I ask you to go back to the last post (Part 1) and scroll through the Comments until you find one from Cathy Yardley, an astute blogger on writing craft and a very knowledgeable contributor. She confessed to being a little confused, too. Which I took to heart.

Believe me when I say, I get that it's probably my fault. This stuff is thick and gooey and nuanced, which is ironic given that my highest objective is to clarify.

Read my response to Cathy's call for clarification.

I'm hoping that'll help.

There's a reason we go deeper into the storytelling experience.

Since I mentioned marriage, allow me to leverage that analogy for a moment.

It's hard. It continues to be hard the longer we do it. We succeed at it, if we ever do, in spite of it being hard, applying what we've learned and tested and grown into along the way. Or not.

Given that easy-to-accept truth, you wouldn't think of saying this:

Gee, this is hard and confusing, so stop telling me what makes a marriage work or not, stop breaking it down into its most basic levels and then providing tools to apply to the challenge, and stop telling me how to make my marriage stellar in a neighborhood full of separations and weekend visitations, which is just, I dunno, normal. Just let me wing it and make my own way, because all that psychological crap is just so darn confusing. I mean, just look at the Joneses next door, they don't ever talk about their relationship and they seem happy as hell.

That's what some writers feel when confronted with the depth of knowledge available about storytelling.

"Just shut up and drive" may work in some relationships, but when it comes to your relationship with your story, it's a recipe for frustration. Possibly a train wreck.

The information and the understanding is out there. We all get to choose whether we wear blinders or reading glasses.

The Feedback

I'm delighted that so many of you "get it." That the relationship between storytelling physics and storytelling tools, and the possibility of storytelling art is, while still challenging, an intriguing and promising can of literary worms.

You get that the recognition of three levels of storytelling experience – essences, if you will – is empowering because it provides a variety of ways to approach and evaluate our work. It's overly simplistic to just ask, "is this good enough?" Especially in comparison to "Is there enough dramatic tension… is the pacing right… will my reader feel the vicarious experience of my hero and root for her or him on that path… and is the conceptual centerpiece of the whole thing going to be compelling enough to anybody but me?"

Which question(s) gets you further, faster, and with better outcome? The ones that are based on an understanding of dramatic physics, that's which.

One reader commented that these levels and all these component parts and realms and essences and tools and empowering hoo-hah (my words, not his) is starting to feel like Buddhism (apologies to enthusiasts for that belief system, those are his words, not mine).

Which translates to: why is this so hard? Why can't we just write our damn stories and not worry about all this "stuff"?

I'm sorry this is hard. I'm not the one making it hard. I'm one of the guys – for better or worse – trying to bring clarity to the inherent difficulty of it. And in doing so, hopefully add to the bliss of it.

Clarity comes from breaking things down into their component parts, and then examining the relationships between them to help us make better choices.

Just like in marriage. And in health, investing, spirituality, even politics.

As in life.

Even when it all seems so… complicated.

Another reader expressed concern that the underlying physics and the six core competencies tended to sound like the same things, or at least overlap. A fair assessment, and a great can of worms to open.

Because they are, and they aren't.

Breaking It Down

If you don't like the term "physics" (my editor at Writers Digest Books didn't, by the way), then call them literary forces or fundamental qualities. What you call them is less critical than how well you understand them.

Or better put, understand how essential they are.

These forces are like gravity. They simply exist. Deny them and you're still stuck with them. Harness them and you can achieve things like flying and dancing and hitting balls for fun and profit.

I've broken them down into four areas that writers should grasp (my opinion), because each stands separate and alone – yet related and dependant – in a story that really works.

They are:

- dramatic tension (conflict in the story)

- vicarious empathy (we root for the hero, we care)

- pace (how quickly and how well the story moves forward)

- inherent compelling appeal (why anyone will want to read this)

These natural dramatic forces are not tools, per say. They are, however, what make writing tools and models and processes effective, because such things are designed to harness — optimize – their power.

And that's the difference between the four forces – physics – of dramatic theory, and the Six Core Competencies that allow us to access and optimize them.

The Six Core Competencies are tools.

They are based on physics, and they describe the physics, but they are not the physics.

They are an operations handbook to the physics.

You could argue, perhaps, that they somewhat overlap with the four forces (essences) described above, but they're really a defining context and a list of standards, criteria and elements that allow the writer to optimize the physics.

A concept – one of the six core competencies – touches on all four of the inherent set of physics (forces, essences) in a well told story.

Characterization focuses on three of them.

Theme touches all four.

And structure… that completely defines how effectively all four will perform.

Scene execution is the means by which all four happen.

Writing voice is the delivery vehicle, squeaky wheels and all.

Still confused?

Allow me one more shot at an analogy here in an effort to clarify.

The physics of cooking are: heat, food, seasoning, presentation. They aren't things, per se, they are qualities. They aren't even activities until, well, they are put into play. They are what you have to work with. They are what you seek to optimize. You deal with all of them, to some degree (or absence), every time you cook a meal. Leave one unhonored (like, serve the chicken raw) and the meal will bomb.

None of those, however, stand alone as a recipe. They are the raw materials, the variables, of a recipe.

A recipe is, in fact, a set of core competencies that coalesce into a strategy and a plan that allow you to optimize those four forces, or variables in the cooking equation. Each one of those four things – heat, food, seasoning, presentation – can be understood, applied and put on a plate in any number of combinations.

The core competencies of cooking are what allows you to optimize those forces. To harness their power for good, for effectiveness. The core competencies become a recipe. And not necessarily a formulaic one (you still get to pick the china, determine the strength of the spices and decide between rare and well done). You still select the levels you desire to put into the outcome, from a pinch to a pint to nothing at all.

And if a recipes calls for you to zest a lemon, which is a skill-based activity, then you'd best understand what that means, practice it, perfect it and nail it. Especially if your goal is to cook professionally.

Or you could just wing it, make it up, or skip it altogether — because this is so freaking hard! — and take your chances.

In our stories, the Six Core Competencies are a set of tools that allow the writer to understand and optimize the raw forces from which a story is made. The better you apply them, the better the story.

Physics are just there. Wai ting to be used or abused or worse, taken for granted. Waiting to help you or kill you. They are eternal.

They are waiting for your creative choices and tastes.

The Core Competencies are a means by which to make sure that what you serve your audience is both delicious and nourishing, and in a way that allows you to impart your own touch.

A set of tools. Working with a set of physics.

Which leaves us with the third realm of writing experience (again, the first being physics/forces/essenses, the second being the six core competencies, or however else you wish to label them: and that is the polish, the final veneer.

And therein, in what has heretofore been craft, resides the possibility of art.

Whether by design or by pure blind stumbling luck… whether by trial and error or focused intention… whether after decades of effort or after a single informed and enlightened draft…

… art doesn't stand a chance until craft has been served.

And craft, no matter how you define or apply the tools, is totally dependant on physics.

My book — "Story Engineering: Mastering the Six Core Competencies of Successful Writing" — has recently been published by Writers Digest Books and is available at most bookstores and online venues.

Image courtesty of Eric Fredericks, via Flickr.

Part 2: A Deeper Understanding of Craft is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 17, 2011

A Deeper, Richer Understanding of Craft

I used to think that the title of this post describes what we are all out to achieve as writers. That this is, in fact, a description of the writing journey as well as the destination.

Not so sure anymore. I'm certain that it can be – and I suspect that it should be – but I'm more convinced than ever that it doesn't have to be, nor is it always so.

Like the song says, some girls just wanna have fun.

Some even get rich and famous in the process.

The more I study this stuff, though, the more convinced I am that, whichever side of this fence you are on, a richer level of understanding opens deeper access to a set of empowering tools and principles that might otherwise prove elusive. A set of criteria, checks and balances that allow us to optimize our stories both before, during and after we've written them.

Imagine if you could look at the story you are about to write, and/or the story you've just finished, and assess it in context to something that is universally true and essential – a set of forces and principles and criteria that exists whether you acknowledge them or not – wouldn't that be a good thing? I think it would be.

Without such an understanding… well, you're stuck with your instincts and the mathematical probably that you've hit the target as close to dead center as you possibly can. That there are no better creative decisions left on the table that trump those you've already made.

In other words, a crap shoot. And in a game that offers you a path to bettering your odds.

Some writers get to the promised land placing these kind of bets. Others spend decades waiting for their horse to come in.

I say, learn how to build a better horse and watch what happens.

You can wait for the game to come to you, or you can go after it.

As it is with sports and music and other forms of art – even in relationships and business and our health – it certainly is possible to dive in, experiment, learn, grow your instincts, get better and advance along the storytelling path – perhaps even to a professional level – without aspiring to truly understand what you're up against and what, as a result, you are up to.

Or, put another way, to break it all down into its component parts.

We know we need to cut down on calories to lose weight… but do we always know why? The science behind it? The real analogous question here is, would we be better at it if we knew why?

Would our options increase and our risks be mitigated if we knew?

I think so. Doesn't mean you can't lose weight simply by skipping lunch and not sweating the details. It also doesn't mean you'll end up reaching your goal, or possibly paying the wrong price to get there.

Unless you seek to become a professional nutritionist. Then it matters that you know.

Sometimes a result is a natural outcome of an organic experience over time (like skipping lunch). Sometimes it's just too much fun and too rewarding to allow a story to just flow out of you, instead of sweating the underlying principles that make it work.

I'm not talking about planning.

No, this mindset is as effective if you plan as it is if plod (pants) your stories.

I'm talking about the application of criteria, principles and even instinct that is based on something bigger than yourself, outside of yourself. Something that is true for everyone, before and after your time on the writing stage.

As important to writing as, say, gravity is to playing golf or flying airplanes.

We can't alter the physics that make a ball curve in mid-air when thrown properly (or a golf ball curve in mid-air when struck improperly)… make a song pierce the heart like a whispered truth from God… or make a painting into an unforgettable frozen frame that captures the essence of the soul itself.

We can ignore them and hope for the best, betting that our instincts make up for our ignorance or rejection of what is true.

Fact is, a set of underlying physics are at work in these outcomes whether the athlete or artist acknowledges or leverages them or not.

For those who seek to understand what storytelling craft is all about at a deeper level – an understanding that can lead to a steeper learning curve and a hastened outcome as well as jacking the fun factor through the roof – I offer the following.

There are three realms inherent to the storytelling experience.

These aren't issues of process as much as they are issues of essence.

A cynic could easily mush them together into a single breath of creative exhilaration and call it good, labeling them as different takes on the same thing.

But storytelling absolutely can be broken down… into three different realms or essences. Those who see them as separate essences are uniquely equipped to optimize their stories, and in a way that those who don't or won't cannot.

If you are building a structure – a bridge, a house, a strip mall – or writing a novel, there are three essences in play. Three levels. Three focuses. Three forces. Three stages. Three contextual lenses through which to view your project.

And they are paradoxical, because they play out in sequence, and then at a certain point they combine to play out in simultaneous three-part harmony (intentional mixed metaphor). You can look at them backwards, retroactively, sequentially or melded and gain great value… or you can harness them out of the starting blocks and also gain value.

Or you can ignore them and hope that your instinct, rather than your proactive hands-on working knowledge of them, will have imbued your story with what they provide.

They are:

- the physics that allow a structure to bear weight and hold together in a stiff wind…

- the blueprint that shows how the structure will hang together, a plan that comes together as the result of the discovery of what the end should look like…

- and then the final coat of paint and polish and artful touch that makes the structure an aesthetic, qualitatively judged piece of real estate.

There exists only one set of underlying physics.

Those physics comprise the first realm, or essence, of storytelling. Or of any craft. They don't care whether you recognize them or not, because they will rule your outcome in spite of you.

But you should care. Because to not recognize, say, the physics of story pacing in your novel is to leave that essential quality up for grabs.

Name your field of endeavor, you'll find that these three realms or essences apply in some form in evidence: the physics that govern it all… the search for effective application… refinement . That the last one is what separates the successful from the masses who apply the same set of physics and tools.

Notice, however, that the reverse isn't true.

Form over function may work in interior design, but its a deal killer in storytelling.

It is literary physics… discovered and pro-actively applied with a set of tools used in the search for story… that provide function for the layer of paint that is the sum of your words.

Stay tuned… I'll go over the three realms of the storytelling experience in my next post.

A mindset is a beautiful, powerful thing once ridded of limiting beliefs.

A Deeper, Richer Understanding of Craft is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 13, 2011

Storyfixins… Weekend Wanderings, Wonderings and other Wistful Wackiness

"The Help"… nails it.

I'd mentioned that I'm reading Kathryn Stockett's "The Help" in preparation for serving up a series of analytical deconstruction posts here on Storyfix. Saw the movie preview today (film comes out in August), which reminds me to remind you that the series will apply to that, too.

Perfect timing, I think. Read the book now, if you haven't… we'll kick it around together in depth… and then, when the movie comes out, we'll all feel like we were sweating it with the screenwriter each step of the way. It's an amazing feeling to see something that you understand deeply, at the core of it's literary being, come to life before your eyes.

It's the best learning tool there is.

Why "The Help"?

First off, any novel that clears the fence in that fashion (as in, a home run) warrants our attention. Also, it's not your typical genre story, it's adult contemporary fiction that approaches what some prefer to call (in contrast to genre fiction) literature in terms of intention, execution and the level of respect shown by reviewers and readers alike.

There are cynics out there that — still — cling to the belief, even the hope, that literature or genre-neutral stories are somehow immune to the principles of story architecture and the six core competencies that drive it, if for nothing else than the fact that such stories are often character-driven to an extent that plot milestones and contextual scene missions can be challenging to recognize, and therefore, become easy targets of debate.

And, the hope that there is something magical afoot. There isn't.

But there's no debating the integrity of the structure in "The Help."

I'm happy to report that "The Help" delivers its First Plot Point right on time in the sequence of the story. If you've had any doubt or lack of clarity on this issue, this deconstruction (and indeed, the book itself) will set you straight — it's right where it's supposed to be. No sooner, no later.

And not because of some rule.

Rather, because that's where the mission of the first plot point – how it impacts and shifts a story – is most effective. When some writers rail against what they insist on calling rules, they're disrespecting what works (and always to their own detriment, and to that of anybody that believes them and reads their work), not some self-concocted notion of creative restriction.

The First Plot Point in "The Help" happens on page 104 of the newly released paperback (out of 530 pages, or just shy of the 2oth percentile mark), and everything that takes place prior to this moment — about 15 scenes delivered within six chapters — serves the textbook definition of the "Part One set-up" scene context, including a killer hook and the establishment of time, place, main characters, stakes, sub-text, sub-plot, pre-Plot Point worldview and foreshadowing.

The whole Part 1 enchilada, in textbook form. How cool is that?

Sorry if this disapponts any naysayers still out there, but you'll have to look elsewhere to disprove the principles of story structure. Unless you go back a century or two, good luck with that.

But… did Kathryn Stockett even know?

Or was this just a happy literary coincidence?

Answer: doesn't matter.

Nor does her writing process matter. Because whatever it is, it drives toward implementing the fundamentals of what makes a story work on the page, at whatever stage along the way that she happened to arrive at that moment.

Sports analogy warning: When Tim Lincecum throws a killer 96 miles per hour fastball on the corner at the knees, does he even know the mechanical principles of physics that allow his less-than-massive body to achieve such stellar performance? Or is he simply practiced and skilled enough to do what needs to be done in the moment to deliver the best possible pitch? Doesn't matter there, either.

It just happens. Rarely by accident or coincidence. Even when it cannot be explained by the doer.

When skilled professionals deliver near-perfection, it is almost always in alignment with the principles of literary physics that do explain it. Even if they just got lucky that one time.

It behooves all of us striving to achieve that level of excellence to seek out and understand the reasons why things work. "The Help" can assist us in that behooving.

Stay tuned for more reasons "The Help" is still kicking butt on the bestseller lists, and why it can and should be held high into the light of analysis and even skepticism to become a model story with much to teach us about the how and why of storytelling.

Send me your poor and broken stories.

Or, any manuscripts you think are ready for primetime.

I'm filling up my summer calendar with stories to analyze for writers who are willing to risk and share and be open to coaching. For a limited time I'm discounting my fee for this work — $1000 for a 400 or fewer page manuscript; an additional $2.00 per additional page; write me for a quote on a shorter treatment and beat sheet analysis. Takes about two to three weeks, and the result is a rich "coaching document" that analyzes the story in context to the six core competencies, with creative alternatives and solutions offered for issues that aren't, in my opinion, optimized in your draft.

Can you handle the truth? I hope so. Because if you don't hear it from me, you'll certainly hear it in less precise form from someone else who is less willling to help you fix whatever needs fixing.

Let me rock your writing conference.

I also do keynote addresses and conduct writing workshops that entail anywhere from one hour to a full two days of intense banging on the craft of storytelling. Just got back from one in Salt Lake City, and I'm still catching my breath (I do get a little excited up there), as are the folks with whom I shared those illuminating and rewarding hours.

References available. Tons.

I'll work with your budget, but as a win-win target I look for expenses (air and hotel) and, depending on workshop length, at least a grand or so. For a full day or two of workshopping, something reasonably more than that. But when I say I'll work with you, I mean it, tell me what you need and what your parameters are.

This notion isn't just for large conferences, either. I've done "private" workshops for writing groups wherein the participants pool their resources and work with me in a smaller venue. Do the math, it becomes pretty reasonable if the headcount is as low as 10 or 15 folks.

There's something powerful about real-time give and take, and that's what happens in my workshops. We all walk away better at what we do — me included — and, usually, a bit hoarse and tired. But not tired enough to stop the adrenalin from kicking in to fuel a new assault on your WIP from an enlightened, energized and fresh point of view.

Book review misinformation.

It's still happening. People are reviewing my book, generally with gracious favor, but occasionally with some interesting feedback.

Feedback is good. I've just offered to sell you mine, so of course I need to be open to hearing it. What I'm hearing is that the first couple of chapters of "Story Engineering" are, well, trying for some readers. That it takes too long to get to the meaty point of it all.

Not the first time I've heard that… about my workshops… my blogs… my own stories. Even lectures to my son and romantic overtures to my wife. So you have my attention.

Most of these readers go on to state that the content, once they get there, is what they came for. A few try to pigeonhole it as something more appropriate for newer writers — a great many seasoned writers disagree — and some just can't get over that patience-dependent first impression.

I can see how this perception happens. Anything I say about it at this point risks defensiveness, but I prefer to think of it as explanatory. It's simple: this material is new. It flies in the face of what many writers have come to accept as solitary, gospel truth. And so, in my sometimes lengthy view, it merits explanation, set-up, paradigm shattering and attention-getting.

That's it. It's there because it might not work as well if it wasn't.

The first Protestants had the same problem. And they were dealing with the same book as their nay-sayers.

But there's another level of input I'd like to address… again.

And that's the occasional misinformation that a few reviewers are putting out there. Along the lines of, "what Larry's saying is (insert issue)… and it's wrong." It would be one thing if what they perceived me saying was quoted accuratly and then labeled as wrong, but that's too often not the case.

Too often a reviewer is describing their perception of what I've said, then wrongly assigning that misperception to me, and then bashing it. When they're just plain wrong about quoting what I've said — not the perception of it, which is their right, but the actual nuts and bolts of it — then it serves nobody, reader or author or reviewer.

The first two are misled, and the last is misspoken.

An example: in a review posted today, a reviewer claims I've contradicted myself when I say in the book that "The Davinci Code" and "Raising the Titanic" are examples of killer concepts and of sub-par characterization. He claims this contradicts my contention that all six of the core competencies need to be rendered at a professional level.

He couldn't be more wrong about these examples being contradictions. Because he fails to quote the rest of the standard: only one or hopefully two of the core competencies need to be stellar – which he agrees the concepts for these two books are — to break out as a bestseller, while the other five need only be professionally adequate. Which I clearly state that they certainly are. I also say the characters in these two books are not particularly, overwhelmingly stellar, that characterization is not the reason (I said that only about Davinci… I would never say that about Dirk Pitt in the Cussler book, because Pitt is an iconic character) those books were runaway bestsellers.

So I need to clarify. Which I hope I just did. Classic over-simplification, implication and flawed perception.

Which, ironically, are things that undo us not only as reviewers, but as storytellers, as well.

Storyfixins… Weekend Wanderings, Wonderings and other Wistful Wackiness is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 11, 2011

Putting the Character into Characterization

I've stumbled upon the magic pill of effective, compelling characterization.

Me and a million other people who write about writing, and/or simply study and write stories. It's been there all along, in certain stories, at varying levels. And while I noticed… I really didn't. Not like this. Not with this new empowering understanding.

Just like the internal architecture of story parts and milestones – which have also been there all along – the sudden recognition and understanding of what you're seeing (and what I am about to share with you) can change everything about your ability to write compelling characters.

This is huge. Get ready to go to the next level.

Like much about grasping and then describing what it takes to write a great story, this is as much about recognizing and verbalizing the essence of something that resists description as it is leaving it to literary instinct or experiential happenstance.

Instinct and happenstance can take decades. A well-worded, illuminating description can unlock something powerful within a writer in the time it takes to read a single sentence.

Or in this case, a single blog post.

Excellence in characterization is about mastering subtlety and nuance.

Such nuances are too easily passed off as talent or even genius.

And while that may be true in some cases, it's also true that once you can see it on the page or screen you are suddenly able to own it for yourself as you write your own stories. Genius or not.

Nuance cannot be fully appreciated until one first grasps the fundamentals, which are unto themselves eternally challenging. There is no negotiating the order of that evolution.

In my book I describe several facets of basic characterization techniques: backstory, inner conflict versus exterior conflict, character arc, the three dimensions of characterization (themselves infused with much subtlety and nuance), the seven realms of characterization… all within the context of a journey, quest or need thrust upon the hero by the author.

That's the 101. A class from which we should never consider ourselves graduated.

But there's more to it where compelling character excellence is concerned.

I'm currently reading "The Help," the blockbuster by Kathryn Stockett, which will be released as a film this summer. I'm preparing a comprehensive deconstruction series on this book to run here on Storyfix concurrent with the release of the film.

Yeah, get excited, this will be killer.

I found myself hooked on this story from page one, and by page 10 I knew why, even though there wasn't yet a plot-specific hook in play beyond a bit of clever foreshadowing.

No, in this novel it was the rarest of hooks that grabbed me… me and about five million other readers.

Not all books have legs like The Help, or The Lovely Bones or Freedom.

This is why.

The reader is immediately hooked by the character.

And I wanted to know why. And therein came my breakthrough.

It's more than voice (though voice is certainly a tool toward this end), and it transcends the first dimension essence of characterization (surface affectations and the manipulation of exterior perception) to drill straight into the compelling third dimension realm, where true characterization resides.

It's a deliberate, contextual approach adopted by the author.

Here it is, in a nutshell:

The most compelling way to suck us into a story and have us immediately understand and root for a character (or hate them, your call) – the best way to give your story a shot at huge success – is to show us how the character FEELS about, and responds to, the journey you've set before them.

This means character surfaces in the here and now, and along the path to come. This is the hero's humanity, for better or worse. Their opinions, fears, feelings, judgments and inner landscape of response to the moment.

It goes far beyond showing us what they say and do.

The writer who commands this advanced technique of characterization isn't just showing us what happens. No, it's so much more than that. They're allowing us into the head of the character as it happens, and in a way that allows us to…

… interpret (or misinterpret), emotionally respond to, assess, fear, plan against, flee from or otherwise form opinions about…

… all that is going on for them in a given moment or situation.

This is, at a simplistic level, called point of view.

But it is an informed point of view, because we are made aware of how the world, the moment, feels and how it is interpreted by the character. And in doing so, we immediately empathize.

The key word here is interpreted.

Getting into Aibileen's head.

In "The Help," we live this story from the point of view of Aibileen, a "colored" maid working for an ignorant, prissy white housewife social climber in 1962 Mississippi. We are immediately thrust into this world from her point of view, which is fraught with racial and social prejudice, injustice and corruption to an extent it feels unbearable and unfixable to someone like her, in this time and place.

But Aibileen is the epitome of the literary hero. Because she does what all heroes do: she summons courage and vision to solve a problem that seems unsolvable, but that must be solved. Because the stakes outweigh the risks.

This essence surfaces within just a few pages. All because of the author's command of nuance in connecting us to the inner emotional and intellectual landscape of the hero's experience.

It is genius? Absolutely. Is it learnable and achievable by other writers? Also absolutely.

It's more than characterization. It's mind-melding the hero with the reader from an emotional, analytical and sociological point of view.

When done well, it's the magic pill of characterization. Empathy, leading to rooting, is the most empowering thing a writer can achieve in the relationship between hero and reader. It is the whole point.

Look for it. See it. Notice how huge, iconic books have it, and how other books – even when they are entertaining, successful, funny and/or suspenseful, often don't.

And then, once you get it, strive to own it in your storytelling.

In your experience, what stories optimize this advanced essence of characterization to help it rise to iconic status?

Once understood, once recognized, you can't put this toothpaste back into the tube. Welcome to the next phase of your writing journey.

Putting the Character into Characterization is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 8, 2011

Suffering is Optional

Yesterday, just before going into a room to give a keynote address to 800 hungry and refreshingly hopeful writers, my wife said this to me over the phone:

"Be positive. You don't need to tell them how hard this is."

Good point. A keynote is perhaps not the time to reflect on the height of the bar.

If I hadn't already been down this road I might not hold that view. I'm still dealing with the fallout from a 2009 keynote in which I told 500 equally hungry writers this: "If you gathered all the Big Career Famous Writers in this entire state, they'd fit into a booth at Denny's."

The room split like Congress listening to a State of the Union address.

Hey, I was just trying to help. To get them to buckle down and take craft as seriously as it needs to be taken. Just as seriously as the stuff some writers seem to prefer to discuss at conferences, like how to land an agent and how to market a book.

The cart called, it wants the horse back.

So now, as I write this, I'm at the airport going back to reality – always the feeling when departing a writing conference in which a brotherhood of common interest and shared challenge permeates every conversation – and I just have to let it out.

And this should never divide a room, because it's inarguably true:

Writing a great story is hard.

Even when the initial seed of the story came easily and the first few chapters drip like butter onto the keyboard. As with a successful first date fueled by ridiculous sexual tension, there is much to encounter and negotiate just around the bend when that particular context wears thin.

Falling in love with your story is easy. Making it last, and then transferring that love to someone you don't know… not so much.

Which is, perhaps, why Moliere said that writing is like prostitution. You've heard that one, I'm sure.

There are so many things we need to understand and put into play as we expand our ideas and instincts into a fully functional story. What those things are called – many of which offend writers who cling to a priority on art over craft, sometimes to the exclusion of craft – isn't as critical as how they come to eventually manifest on the page.

Call them what you will, standards, criteria and expectations exist.

With so many ways to make a story great, we must accept that there must also be a plethora of ways to screw one up.

That has to be true, given the math: unpublished manuscripts outnumber published (or even agent-represented) manuscripts by a factor of…

… well, I'd be guessing on that one. I'd say about 500 to 1. And that doesn't count self-initiated digital books, which haven't impacted the statistics yet in a way that anyone can attach meaning to.

That sad proportion is a call to get deadly serious about our craft. To let go of limiting beliefs that are without basis in either experience or logic.

Lack of ability or experience aren't the leading causes of rejection. Limiting beliefs are.

The best way to avoid a hole in the road is to see the hole in the road.

Suffering is optional. So here goes.

1. Never begin writing a story without knowing how it will end. Even if you hate "story planning" to the core of your being, you don't stand a chance until you write the thing in context to how it will end.

Even if you change your mind mid-stream. Always have a target outcome.

Do what you have to do – write drafts, post yellow sticky notes, whatever – to search for your story, or at least its ending.

2. If you choose to ignore the previous tip, then you'd best accept this one: if you stumble upon an ending (or change it) mid-draft, you most likely will need to start the whole thing over, or at least engage in a process of review and revision to accommodate the newly present context of the ending you have in mind, which, if done right, will feel like a rewrite.

Yes Virginia, the ending does, in fact, provide the primary context of a story. If you begin writing without one you are writing without context, and that's almost always a fatal mistake, often one born of a limiting belief system about how a story is written.

3. Don't kid yourself about the critical nature – the necessity – of structure in your story. You can't skip or skimp on set-up, and you'd best have a handle on what an inciting incident is, what a point plot is, the difference between them, or not, the mission they must embrace, and where they are optimally located in the sequence of things. If you're guessing or ignoring, then you're rolling the dice on the future viability of your story.

Sure, you can guess right. You can win the lottery this way, too.

All of information required to write from an informed and enlightened context is out there. Its in here. It's available. To not pursue that knowledge is to dishonor the very avocation you claim to hold dear.

Unless, of course, you are the next literary prodigy. Let us know how that's working out.

4. Don't take side trips. Your narrative – regardless of genre – needs to adhere to a forward-moving spine and focus.

5. Don't write a "small" story without something Big in it. If your story is about your grandmother's childhood in rural Iowa, you'll have a better shot if she turns out to be a Senator born of a minority race to same-sex parents in the deep south before being sent to an orphanage in an era long before Lady Gaga informed us that some folks are just "born this way."

Every writer must decide who they are writing for. If the answer is, "I'm writing this story just for me, anything else that happens is gravy," then you are operating under a limiting belief system. Short of the isolated example it doesn't work that way.

The moment you declare you are writing professionally, everything changes. Including any legitimacy when it comes to making up your own storytelling principles, paradigms and standards. In that case the change is this: all assumptions of that legitimacy are rendered invalid.

6. If you can't describe your story in one compelling sentence, you probably can't write it in 20,000 compelling sentences, either. Why? Because to write a story successfully, you need to be in complete command of what the story is about, at its highest level of intention and focus.

An enlightened writer knows they need to work on that one sentence before they work on the other 19.999.

That single thing – what the story is really about – is the driving force of the entire storytelling effort. It creates context for everything on every page.

7. Don't save your hero. Rather, show us your hero earning the title. Your hero needs to be the primary, proactive catalyst in the story's resolution. Never a spectator to it, never a victim to it by the time the cover closes. Even if the hero ends up dead – it happens – your job is to show the reader some sort of redemptive success in the journey you've sent them on.

8. Don't for a moment believe that the things an established bestselling author can get away with are things you can get away with. And don't even hint at leveraging any isolated examples to the contrary to justify any compromise to the fundamentals that will allow your story to shine.

9. Don't overwrite. One man's perfume is another's stench – been to a cigar bar lately? – so don't cloud the air with your words. Less is more. Be clever, be ironic, have an attitude and a voice and a world view. Maintain a light touch with it, ala Nelson Demille.

Like the schmuck at the last party you went to that wouldn't shut up, don't suck all the air out of the story with your attempt to impress with words.

10. Never settle. Look at your core concept and ask what you can do to make it stronger. Look at your characters and ask how you can make them deeper, more compellingly complex and likely to elicit reader empathy, which also embraces the nature of the journey you've sent them on (plot) and the obstacles you've placed before them.

Ask yourself if your story will matter to anyone but you, if it says anything at all about the human experience.

I could rant on, as the list is long and dark. As is the list of things we can do to make a story sing.

So instead, allow me to conclude, for the moment, with this:

Even when you know the tools, it's still hard.

It's hard because it's complex, layered, nuanced and always resides on a landscape already occupied by the ghosts of stories that have come before. The trick isn't to reinvent something, the trick is to play big within the box into which you've willingly climbed. To bring freshness and energy to your tale.

There are standards, criteria and tools that help us do just that, and that will bail us out when we lose our way.

And everybody loses their way. The math proves it.

It's the writer who not only recognizes rough water, but has the presence of mind to realize when they're drowning and make a compensatory shift driven by their knowledge of craft, that snags an agent, a publisher and/or a readership.

So now – as my friend Bruce Johnson says – go write something great. And do it in the comforting knowledge that the physics of storytelling apply equally to everyone… at least until they're famous.

A new definition of irony, that. May we all discover it for ourselves one day.

Read more about "Story Engineering," including reviews, here.

Suffering is Optional is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com

May 5, 2011

Opinions are like… manuscripts. Everybody's got one.

Ours is an opinion-driven avocation. From stellar manuscripts that are regularly tossed under the bus to the same old worn out A-list mediocrity, it's all a bit of a paradoxical crap shoot.

We writers have opinions about more than the end product of our efforts. We have opinions about what a story should be. And, more germane to this site and this post, how to write one.

Well duh… especially me. I just wrote a book about it. Doesn't make my opinion perfect or better than yours, it just makes it, well, a target. One that, according to feedback, is smack on the mark for many. Not all of whom are new at this.

Not that I'm uncovering anything new here.

Just rearranging, clarifying and separating the myriad facets of storytelling into some newly cast buckets.

As I consider this post, I'm sitting in a Sheraton in Salt Lake preparing to give a keynote address tomorrow at a large writing conference. And then a workshop on Saturday. Am I nervous? Always.

About the content? No. About a room full of opinions which at this point are up for grabs… absolutely.

You see, I want them to get it. To understand that I'm not challenging their status quo, I'm expanding and empowering it.

The nice fellow who picked me up at the airport today informed me that half the room (my perception, not his precise words) tomorrow will have been published. In fact, he's been published. The woman who was in the car with us has her first book coming out in a few months. With the explosion of digital self-publishing, everybody who wants to lay claim to being published can do so.

That, however, is no longer the point. Storytelling is the point.

The conversation reminded me how humbling this writing guru thing can be. I'm certain that the room will be well stocked with writers who are more talanted than me, more successful than me and, for better or worse, have opinions about writing that are different and more evolved than mine.

And that's cool. I'm here to learn, too.

In fact, my new friend told me about one published novelist who will be in the room (gotta admit, hadn't heard of him, just as I'm sure he's never heard of me) who said that we should forget all this structure nonsense, that a novel only needs three things to work.

Those three things weren't specified.

Another opinion joining the chorus. Can't wait to meet that guy in the foyer after my speech.

I'm not threatened by better and more successful authors than myself — happens everywhere I go — in fact, it's fun to swap stories and bat ideas around. Truth be told, the more successful the author, the more likely they are to buy into my Six Core Competencies approach, for the most part (two words: Terry Brooks). Because when you boil it all down — the different ways to describe how this should be done – most informed views are basically recasting the same set of fundamentals within different paradigms cloaked in different words.

You say potato, I'll say patatto, and we'll both put the same gravy on the outcome.

And it's all good. The more we hear it, explore it, debate it and rip into it, the more we'll understand about the art and craft of storytelling.

As long as you don't believe the earth is flat, the moon is made of cheese and stories don't hinge on certain physics and principles. Those aren't opinions as much as they are some combination of denial and naivete.

And they're out there.

You see, they wanted this writing thing to be fun. To be spiritual. To be something they could invent for themselves. They don't want some guy — any guy — telling them that they should do this or that with their story, they want to just make it all up for themselves as they go.

Imagine if your surgeon or your airline captain or your lawyer believed that about their craft.

A shame, that. Because the truth about the fundamentals of successful storytelling is available to everyone, and the means and timeline of discovery are completely within our control.

All this brings me back to a life principle that is wildly, ragingly, in play in the writing world:

We are what we think. And we bear the consequences of who we are.

If we reject structure, then we are unstructured. If we reject principles, we are unprincipled. If we reject teaching, then we reject learning. And in doing so, we limit ourselves.

So here's the question for today: is your opinion about the writing process and the underlying physics and principles of effective storytelling empowering you, or limiting you?

Simple question. With unfathomable consequences for writers with serious intentions.

In my humble opinion, the art of writing resides in the way principles of dramatic fiction are grasped, rendered, stretched and made profound — through craft – rather than the way they can be circumvented or ignored.

That's not art, that's narcissism wearing the face of naivete.

As T.S. Elliot said:

When forced to work within a strict framework, the imagination is taxed to its utmost… and will produce its richest ideas. Given total freedom, the work is likely to sprawl.

And so tomorrow, I will chip my opinions about storytelling into the crowd in the hope that someone out there finds clarity that has eluded them. And that the guy who thinks a novel needs only three things realizes we're already on the same page… only mine has more lines.

Click HERE to read reviews of Story Engineering: Mastering the Six Core Competencies of Successful Storytelling, the #1 bestselling fiction craft book on Kindle.

Opinions are like… manuscripts. Everybody's got one. is a post from: Larry Brooks at storyfix.com