Sam Thomas's Blog, page 3

January 13, 2013

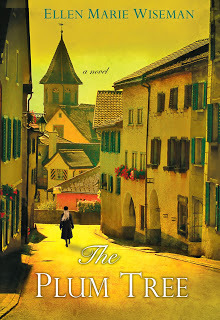

ELLEN MARIE WISEMAN ON 'THE PLUM TREE'

Thank you to Nancy Bilyeau for inviting me to talk about the research I did for my novel, THE PLUM TREE.

When I started working on THE PLUM TREE, a WWII story about a young German women in love with a Jewish man, I knew the setting like the back of my hand—a small village in Germany surrounded by rolling hills, orchards, vineyards and medieval castles. I’d been to Germany numerous times to visit family and could picture the cobblestone streets and stepped alleys because I had walked them myself. I could smell the aroma of pretzels and tortes coming from the village bakery and taste the warm, dark beer being shared at the corner Krone. I could feel the soft cocoon formed by sleeping beneath a deckbed (feather bedcover) and hear the church bells echoing through the narrow streets. I could even get a sense of the fear and claustrophobia caused by wartime air raids, because I’d been inside the bomb shelter where my mother and her family hid in terror for nights on end.

When I started working on THE PLUM TREE, a WWII story about a young German women in love with a Jewish man, I knew the setting like the back of my hand—a small village in Germany surrounded by rolling hills, orchards, vineyards and medieval castles. I’d been to Germany numerous times to visit family and could picture the cobblestone streets and stepped alleys because I had walked them myself. I could smell the aroma of pretzels and tortes coming from the village bakery and taste the warm, dark beer being shared at the corner Krone. I could feel the soft cocoon formed by sleeping beneath a deckbed (feather bedcover) and hear the church bells echoing through the narrow streets. I could even get a sense of the fear and claustrophobia caused by wartime air raids, because I’d been inside the bomb shelter where my mother and her family hid in terror for nights on end. My mother grew up in Nazi Germany, the eldest of five children in a poor, in a working-class family. When I started research for my novel, I asked her to retell the family stories about WWII so I could take notes, going as far as giving her a questionnaire about the details of everyday life. Through her answers, I learned, among other things, how the average German mother kept her children fed and alive during food shortages—domestic practices like making sugar out sugar beets, bartering beechnuts for cooking oil, using vinegar to preserve what little meat they had, keeping chickens safe in the attic, and letting a crock of milk sour on the cellar steps until it was the consistency of pudding, then serving it with boiled potatoes and salt. My mother remembers waking up to find her parents in the kitchen making sausage in the middle of the night because it was illegal to purchase and butcher a pig during the war. They told her they were making tortes and sent her back to bed. Every resource—wood, pigs, flour, church bells, iron gates, scrap metal, paper, bones, rags, empty tubes—was to go towards the war effort. And there were rules about everything, from how often a person was allowed to bathe, to the list of acceptable baby names.

When the war started, my grandfather was drafted and sent to the Russian front. I remember his stories about being captured and sent a POW camp, the deep snow, the freezing cold, the way the prisoners would undress and sleep in a huddle, hoping to freeze the lice off their uniforms. Every morning there would be dead men around the edges of the group, frozen while they slept. Eventually my grandfather escaped, but for two years, my mother and her family had no idea if he was dead or alive until he showed up on their doorstep one day.

During the four years my grandfather was off fighting, my grandmother repaired damaged military uniforms to bring in a small income. She stood in ration lines for hours on end, cooked on a woodstove, made clothes out of cotton sheets, and put blackout paper over the house windows so the enemy wouldn’t see their light. Under the cover of night, she put food out for passing Jewish prisoners and listened to foreign radio broadcasts on an illegal shortwave—both crimes punishable by death. My uncles told me about seeing planes being built in the forest, beneath the canopy of thick trees, and I even had the chance to talk to an elderly man who was a former SS doctor. He showed me his photo album from the war, pointing out pictures of him standing near Hitler, of him drinking schnapps with other officers in front of a huge Christmas tree. He showed me a letter he’d sent to his wife from the Eastern front, and a hand drawn postcard with the image of a giant officer stepping over mountains into Germany, a bouquet of roses in his arms. I soon realized he was a doctor on the front lines, not in the camps, as I had assumed. He recalled the horrible conditions on the battlefields, operating on the wounded in a tent with mud floors, not having enough bandages and morphine.

In THE PLUM TREE, Lagerkommandant Grünstein is loosely based on Kurt Gerstein, a real SS officer who infiltrated the camps so he could witness first-hand what the Nazis were doing. During my research I found out that Kurt Gerstein tried to tell the world what was happening, but no one would listen. When the war was over, he died in a French prison after giving a detailed account of the camps to the Allies. Twenty days later he was found dead in his cell. Whether he committed suicide or was murdered by the other SS prisoners remains a mystery. His testimony provided the Allies with their most detailed account at Nuremburg.

Along with my family’s history, there were a great many books that were helpful to me while writing THE PLUM TREE. Among the memoirs that mirrored and expanded on my family’s stories were: German Boy by Wolfgang W. E. Samuel, The War of our Childhood; Memories of WWII by Wolfgang W.E. Samuel, and Memoirs of a 1000-Year-Old Womanby Gisela R. McBride. I also relied on Frauen: German Woman Recall the Third Reich by Alison Owings. To understand the Allied bombing campaign, which had become a deliberate, explicit policy to destroy all German cities with populations over 100,000 using a technique called “carpet bombing”—a strategy that treated whole cities and their civilian populations as targets for attacks by high explosives and incendiary bombs—I read: To Destroy a City: Strategic Bombing and its Human Consequences in WWII by Hermann Knell, Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombings of Civilians in Germany and Japan by A.C. Grayling, and The Fire by Jörg Friedrich. Among the many horrific air raid stories in these books were the firebombing of Hamburg in July 1943, dubbed “Operation Gomorrah” which killed 45,000 civilians, and the firebombing of Dresden in February 1945, which killed 135,000 civilians. All of these books include some of the most haunting scenes I’ve ever read about what was like to be a German civilian during the war. These books reinforced my belief that this was a story that needed to be told.

To understand what it was like for civilians and POWs after the war I read: Crimes and Mercies: The Fate of German Civilians under Allied Occupation by James Bacque. For information involving persecution of the Jews and the horror of concentrations camps I read: Night by Elie Wiesel, Eyewitness Auschwitz by Filip Müller, and I Will Bear Witness by Victor Klemperer.

Although The Plum Tree is a work of fiction, I strove to be as historically accurate as possible. For the purpose of plot, Dachau was portrayed as an extermination camp, while in reality it was categorized as a work camp. Undoubtedly, tens of thousands of prisoners were murdered, suffered, and died under horrible conditions at Dachau, but the camp was not set up like Auschwitz and other extermination camps, which had a deliberate “euthanasia” system for killing Jews and other undesirables. Also for the purpose of plot, the attempt on Hitler’s life led by Claus von Stauffenburg was moved from July 1944 to the fall of 1944.

Published on January 13, 2013 17:22

January 11, 2013

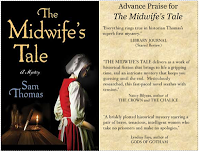

Win a copy of Midwife's Tale!

Sorry for the Internet silence of late, but if you're interested in winning a copy of by Sam Thomas

Giveaway ends February 09, 2013.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Enter to win

Published on January 11, 2013 03:06

January 8, 2013

The Midwife's Tale is now on Sale! (And has a trailer.)

True story: I called a bookstore chain of which you have heard and asked when they thought The Midwife's Tale might come in. (My goal was to stop by and sign whatever copies they had.)

Me: It's called The Midwife's Tale.

Clerk: T-A-L-E?

*Pause while I imagine the plot of The Midwife's T-A-I-L.*

Me: Yes, T-A-L-E.

Anyway, The Midwife's Tale is out today! And here's the Trailer:

Me: It's called The Midwife's Tale.

Clerk: T-A-L-E?

*Pause while I imagine the plot of The Midwife's T-A-I-L.*

Me: Yes, T-A-L-E.

Anyway, The Midwife's Tale is out today! And here's the Trailer:

Published on January 08, 2013 02:02

January 6, 2013

FROM HOMER TO THE HOBBIT: THE HISTORY OF THE NECROMANCER

By Nancy Bilyeau

Vampire. Witch. Zombie. Werewolf. Yes, they have us surrounded.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

When it comes to the fanged ones, I like to get down with Dracula, whether it's in the hands of the one-and-only Bram Stoker, the gifted Elizabeth Kostova (The Historian) or the audacious Francis Ford Coppola in his adaptation (fantastic soundtrack). Anne Rice, Charlaine Harris and Justin Cronin have taken the vampire myth in fascinating directions. And, yes, I admit it: I'm a Twilight mom.

My favorite "modern" witch has to be the determined and erudite Diana Bishop in Deborah Harkness's wonderful novels, A Discovery of Magic and Shadow of Night. She's come a long way from "Double, double, toil & trouble."

As for the rest of the pack, werewolves have their place, I know, but they can't summon up the subtlety of an aristocratic vampire or a manipulative witch. Zombies? I haven't recovered from watching Night of the Living Dead in a college sorority house. I prefer my zombies Shaun of the Dead-style, thank you very much. :)

So perhaps the modern viewer could be forgiven some cynicism when faced with the latest variety of scary being in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey: the necromancer. And what do we have here? Well, something scary for one. The character of The Necromancer takes up very little screen time (especially considering that the movie is a darn 169 minutes long), but it is used to effect. If you don't believe me, check it out for yourself:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBZDFV-VUVQ

Now you see what I mean.

Long ago, I had decided that in my second novel, The Chalice, which revolves around a dangerous prophecy, my protagonist, Joanna Stafford, would come face to face with a necromancer, a person who purports to see into the future using the "dark arts." I plunged into historical research, not knowing what to expect. I was aware of the basic job description of the necromancer: i.e., someone who has special contact with the dead.

The image flitting through popular culture is that of a mysterious yet charismatic spell caster, as in Dungeons and Dragons.

Yet in doing my research, I was shocked to learn that necromancy dates back to antiquity. And just as storytelling that features supernatural creatures such as the vampire tells us something about human fear of aging and sexuality, belief in the necromancer, which shows up in many centuries and many cultures, reveals something of our society's feelings about death and the unknowable future.

The first written references to them were in the 5th century BCE. In ancient Greece necromancers were "evocators of souls," sorcerers who claimed to know how to summon up the spirit of a dead person and, once contacted, glimpse the future. Only they could dissolve the barrier between the living and the dead. Such skills required extensive training; the ceremonies involved drawing circles in the ground, pronouncing incantations, and using such apparatus as water, candles, scepters, swords and wands. Animal sacrifice often played a part in compelling the dead to appear.

In Homer's Odysssey, Book Eleven, Ulysses summons the spirits of dead heroes using the rituals taught him by Circe, knowledgeable of necromantic rites, to learn his fate:

Vampire. Witch. Zombie. Werewolf. Yes, they have us surrounded.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.When it comes to the fanged ones, I like to get down with Dracula, whether it's in the hands of the one-and-only Bram Stoker, the gifted Elizabeth Kostova (The Historian) or the audacious Francis Ford Coppola in his adaptation (fantastic soundtrack). Anne Rice, Charlaine Harris and Justin Cronin have taken the vampire myth in fascinating directions. And, yes, I admit it: I'm a Twilight mom.

My favorite "modern" witch has to be the determined and erudite Diana Bishop in Deborah Harkness's wonderful novels, A Discovery of Magic and Shadow of Night. She's come a long way from "Double, double, toil & trouble."

As for the rest of the pack, werewolves have their place, I know, but they can't summon up the subtlety of an aristocratic vampire or a manipulative witch. Zombies? I haven't recovered from watching Night of the Living Dead in a college sorority house. I prefer my zombies Shaun of the Dead-style, thank you very much. :)

So perhaps the modern viewer could be forgiven some cynicism when faced with the latest variety of scary being in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey: the necromancer. And what do we have here? Well, something scary for one. The character of The Necromancer takes up very little screen time (especially considering that the movie is a darn 169 minutes long), but it is used to effect. If you don't believe me, check it out for yourself:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBZDFV-VUVQ

Now you see what I mean.

Long ago, I had decided that in my second novel, The Chalice, which revolves around a dangerous prophecy, my protagonist, Joanna Stafford, would come face to face with a necromancer, a person who purports to see into the future using the "dark arts." I plunged into historical research, not knowing what to expect. I was aware of the basic job description of the necromancer: i.e., someone who has special contact with the dead.

The image flitting through popular culture is that of a mysterious yet charismatic spell caster, as in Dungeons and Dragons.

Yet in doing my research, I was shocked to learn that necromancy dates back to antiquity. And just as storytelling that features supernatural creatures such as the vampire tells us something about human fear of aging and sexuality, belief in the necromancer, which shows up in many centuries and many cultures, reveals something of our society's feelings about death and the unknowable future.

The first written references to them were in the 5th century BCE. In ancient Greece necromancers were "evocators of souls," sorcerers who claimed to know how to summon up the spirit of a dead person and, once contacted, glimpse the future. Only they could dissolve the barrier between the living and the dead. Such skills required extensive training; the ceremonies involved drawing circles in the ground, pronouncing incantations, and using such apparatus as water, candles, scepters, swords and wands. Animal sacrifice often played a part in compelling the dead to appear.

In Homer's Odysssey, Book Eleven, Ulysses summons the spirits of dead heroes using the rituals taught him by Circe, knowledgeable of necromantic rites, to learn his fate:

Ulysses journeys to the place of ritual

"When the sun went down and darkness was over all the

King Saul "had put the mediums and the necromancers from the land," but "when Saul saw the army of the Philistines, he was afraid, and his heart trembled greatly." He went to the woman of Endor in disguise to learn what would happen in his battle with the Philistines. At first, interestingly, she refused.And Saul said, "Divine for me by a spirit and bring up for me whomever I shall name for you." The woman said to him, "Surely you know what Saul has done, how he has cut off the necromancers from the land. Why then are you laying a trap for my life to being about my death?

Saul revealed himself, persisted in his demand for prophecy, saying, "As the Lord lives, no punishment shall come upon you for this thing."

Saul may have wished he hadn't pushed so hard. Once the Woman of Endor summoned the dead prophet Samuel, he told the king about the looming battle: "Tomorrow you and your sons shall be with me. The Lord will give the army of Israel into the hand of the Philistines."Sure enough, the next day Saul and his sons perished.

In the centuries of Roman rule, divining the future was more important then ever, whether it was paying visits to oracles, reading the auspices, or seeking out necromancers. Astrology, the white art of prophecy, was all the rage.

When Christianity became the religion of the Empire, and, after the fall of Rome, the popes ruled Christendom, astrology and other pagan practices were officially discouraged. Necromancers were detested above all. The religious authorities did their utmost to stamp them out.

But the dawn of the medieval age was not the end of the necromancers. It was just the beginning.

(Part Two: The Hidden Necromancer of Medieval England will appear later this month.)

To learn more about The Chalice—read excerpt chapters, see a Pinterest board, enter a giveaway—go to: http://nancybilyeau.blogspot.com/2013/01/a-sip-from-chalice.html

Published on January 06, 2013 18:30

THE ANCIENT ART OF THE NECROMANCER

By Nancy Bilyeau

Vampire. Witch. Zombie. Werewolf. Yes, they have us surrounded.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

When it comes to the fanged ones, I like to get down with Dracula, whether it's in the hands of the one-and-only Bram Stoker, the gifted Elizabeth Kostova (The Historian) or the audacious Francis Ford Coppola in his adaptation (fantastic soundtrack). Anne Rice, Charlaine Harris and Justin Cronin have taken the vampire myth in fascinating directions. And, yes, I admit it: I'm a Twilight mom.

My favorite "modern" witch has to be the determined and erudite Diana Bishop in Deborah Harkness's wonderful novels, A Discovery of Magic and Shadow of Night. She's come a long way from "Double, double, toil & trouble."

As for the rest of the pack, werewolves have their place, I know, but they can't summon up the subtlety of an aristocratic vampire or a manipulative witch. Zombies? I haven't recovered from watching Night of the Living Dead in a college sorority house. I prefer my zombies Shaun of the Dead-style, thank you very much. :)

So perhaps the modern viewer could be forgiven some cynicism when faced with the latest variety of scary being in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey: the necromancer. And what do we have here? Well, something scary for one. The character of The Necromancer takes up very little screen time (especially considering that the movie is a darn 169 minutes long), but it is used to effect. If you don't believe me, check it out for yourself:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBZDFV-VUVQ

Now you see what I mean.

Long ago, I had decided that in my second novel, The Chalice, which revolves around a dangerous prophecy, my protagonist, Joanna Stafford, would come face to face with a necromancer, a person who purports to see into the future using the "dark arts." I plunged into historical research, not knowing what to expect. I was aware of the basic job description of the necromancer: i.e., someone who has special contact with the dead.

The image flitting through popular culture is that of a mysterious yet charismatic spell caster, as in Dungeons and Dragons.

Yet in doing my research, I was shocked to learn that necromancy dates back to antiquity. And just as storytelling that features supernatural creatures such as the vampire tells us something about human fear of aging and sexuality, belief in the necromancer, which shows up in many centuries and many cultures, reveals something of our society's feelings about death and the unknowable future.

The first written references to them were in the 5th century BCE. In ancient Greece necromancers were "evocators of souls," sorcerers who claimed to know how to summon up the spirit of a dead person and, once contacted, glimpse the future. Only they could dissolve the barrier between the living and the dead. Such skills required extensive training; the ceremonies involved drawing circles in the ground, pronouncing incantations, and using such apparatus as water, candles, scepters, swords and wands. Animal sacrifice often played a part in compelling the dead to appear.

In Homer's Odysssey, Book Eleven, Ulysses summons the spirits of dead heroes using the rituals taught him by Circe, knowledgeable of necromantic rites, to learn his fate:

Vampire. Witch. Zombie. Werewolf. Yes, they have us surrounded.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.

In films, books and TV series, it seems as if the supernatural run the show as never before. I admit to having my favorites.When it comes to the fanged ones, I like to get down with Dracula, whether it's in the hands of the one-and-only Bram Stoker, the gifted Elizabeth Kostova (The Historian) or the audacious Francis Ford Coppola in his adaptation (fantastic soundtrack). Anne Rice, Charlaine Harris and Justin Cronin have taken the vampire myth in fascinating directions. And, yes, I admit it: I'm a Twilight mom.

My favorite "modern" witch has to be the determined and erudite Diana Bishop in Deborah Harkness's wonderful novels, A Discovery of Magic and Shadow of Night. She's come a long way from "Double, double, toil & trouble."

As for the rest of the pack, werewolves have their place, I know, but they can't summon up the subtlety of an aristocratic vampire or a manipulative witch. Zombies? I haven't recovered from watching Night of the Living Dead in a college sorority house. I prefer my zombies Shaun of the Dead-style, thank you very much. :)

So perhaps the modern viewer could be forgiven some cynicism when faced with the latest variety of scary being in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey: the necromancer. And what do we have here? Well, something scary for one. The character of The Necromancer takes up very little screen time (especially considering that the movie is a darn 169 minutes long), but it is used to effect. If you don't believe me, check it out for yourself:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBZDFV-VUVQ

Now you see what I mean.

Long ago, I had decided that in my second novel, The Chalice, which revolves around a dangerous prophecy, my protagonist, Joanna Stafford, would come face to face with a necromancer, a person who purports to see into the future using the "dark arts." I plunged into historical research, not knowing what to expect. I was aware of the basic job description of the necromancer: i.e., someone who has special contact with the dead.

The image flitting through popular culture is that of a mysterious yet charismatic spell caster, as in Dungeons and Dragons.

Yet in doing my research, I was shocked to learn that necromancy dates back to antiquity. And just as storytelling that features supernatural creatures such as the vampire tells us something about human fear of aging and sexuality, belief in the necromancer, which shows up in many centuries and many cultures, reveals something of our society's feelings about death and the unknowable future.

The first written references to them were in the 5th century BCE. In ancient Greece necromancers were "evocators of souls," sorcerers who claimed to know how to summon up the spirit of a dead person and, once contacted, glimpse the future. Only they could dissolve the barrier between the living and the dead. Such skills required extensive training; the ceremonies involved drawing circles in the ground, pronouncing incantations, and using such apparatus as water, candles, scepters, swords and wands. Animal sacrifice often played a part in compelling the dead to appear.

In Homer's Odysssey, Book Eleven, Ulysses summons the spirits of dead heroes using the rituals taught him by Circe, knowledgeable of necromantic rites, to learn his fate:

Ulysses journeys to the place of ritual

"When the sun went down and darkness was over all the

King Saul "had put the mediums and the necromancers from the land," but "when Saul saw the army of the Philistines, he was afraid, and his heart trembled greatly." He went to the woman of Endor in disguise to learn what would happen in his battle with the Philistines. At first, interestingly, she refused.And Saul said, "Divine for me by a spirit and bring up for me whomever I shall name for you." The woman said to him, "Surely you know what Saul has done, how he has cut off the necromancers from the land. Why then are you laying a trap for my life to being about my death?

Saul revealed himself, persisted in his demand for prophecy, saying, "As the Lord lives, no punishment shall come upon you for this thing."

Saul may have wished he hadn't pushed so hard. Once the Woman of Endor summoned the dead prophet Samuel, he told the king about the looming battle: "Tomorrow you and your sons shall be with me. The Lord will give the army of Israel into the hand of the Philistines."Sure enough, the next day Saul and his sons perished.

In the centuries of Roman rule, divining the future was more important then ever, whether it was paying visits to oracles, reading the auspices, or seeking out necromancers. Astrology, the white art of prophecy, was all the rage.

When Christianity became the religion of the Empire, and, after the fall of Rome, the popes ruled Christendom, astrology and other pagan practices were officially discouraged. Necromancers were detested above all. The religious authorities did their utmost to stamp them out.

But the dawn of the medieval age was not the end of the necromancers. It was just the beginning.

(Part Two: The Hidden Necromancer of Medieval England will appear later this month.)

Published on January 06, 2013 18:30

December 9, 2012

A Holiday Gift...From the Future!

by Sam Thomas

I know what you're thinking:

"I'd like to give copies of THE MIDWIFE'S TALE to all my friends for Christmas, but it doesn't come out until January. What should I do?"

(Okay, you might not have been thinking this, but one person was, and he wrote about it after reading The Puzzle Doctor's review of my book.)

Fret not - I've got you covered.

Send me an email letting me know that you've pre-ordered a copy of The Midwife's Tale, and I'll send you a nifty postcard (shown here) with a picture of the cover and some of the nice things people have said about the book. It's got a nice glossy front, and the back features a bit of the jacket copy, and a blank area where I can write a personal note, or you can write your message.

Put that in an envelope (which I'll include free of charge!) and you're all set.

You can reach me through my webpage, Facebook, or the old fashioned way...you know, email.

Happy holidays everyone!

I know what you're thinking:

"I'd like to give copies of THE MIDWIFE'S TALE to all my friends for Christmas, but it doesn't come out until January. What should I do?"

(Okay, you might not have been thinking this, but one person was, and he wrote about it after reading The Puzzle Doctor's review of my book.)

Fret not - I've got you covered.

Send me an email letting me know that you've pre-ordered a copy of The Midwife's Tale, and I'll send you a nifty postcard (shown here) with a picture of the cover and some of the nice things people have said about the book. It's got a nice glossy front, and the back features a bit of the jacket copy, and a blank area where I can write a personal note, or you can write your message.

Put that in an envelope (which I'll include free of charge!) and you're all set.

You can reach me through my webpage, Facebook, or the old fashioned way...you know, email.

Happy holidays everyone!

Published on December 09, 2012 06:39

December 5, 2012

When cases were solved by a corpse’s pointing finger….

Recently I came across the Detective’s Oath, written by Dorothy Sayers and first administered by G.K. Chesterton, as part of the initiation ceremony for the London Detection Club. The club, convened in 1930, included the likes of Sayers, Agatha Christie, and a slew of other Golden Age mystery writers.

The oath was this: “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?”

While I think we’ve all seen authors—well-known ones at that—break these principles regularly (after all, why can’t a ghost solve a crime? Or for that matter, a cat?), there was something to these expectations that made sense. A reader should be able to work out whodunit, at least after the fact, to be fair.

But when I first read the oath, I had to laugh. All three of us—Nancy Bilyeau, Sam Thomas, and myself—have situated our mysteries in early modern England, a time when divine revelation, providence, acts of God (or the Devil, for that matter) often served as the explanation for most mishaps and misfortune. It would have been so easy—and realistic—to have our sleuths solve crimes in that fashion.

After all, there are many incidences of a community “solving” a murder when a corpse’s finger pointed to its murderer. Or when the corpse’s eyes would open and stare in the direction of the murderer’s house. There are even examples of corpses bleeding from the nose or ears, indicating that theirmurderers were in the vicinity.

Sometimes, logic and reason and evidence would prevail and sometimes…they did not. There are many examples of superstitions, hearsay, and feelings making their way into court testimony, especially in ecclesiastical courts.

I can’t speak for Nancy and Sam’s protagonists, of course, but I wanted Lucy Campion, my chambermaid in a A Murder at Rosamund's Gate , to be someone who was resourceful and intelligent, despite having little formal education. But it wasn’t just about creating a character who would use her wits and evidence to solve a crime; I wanted her to question how the community identified murderers in the first place.

I also wanted Lucy to be someone who rejects the notion of providence as a means to explain murder. I wanted her to dismiss the idea that divine revelation could be a reliable way to identify a murderer—even if that meant challenging the expectations of her community.

I’d like to think that Lucy would approve of the Detective’s Oath, even if everyone around her was convinced that the murderer could be discovered by a corpse's pointing finger.

But what do you think? If you're a writer, do you adhere to this oath? Or gleefully stomp all over it? If you're a reader, do you mind if the detective doesn't use logic or wits to solve a crime?

Published on December 05, 2012 21:20

November 26, 2012

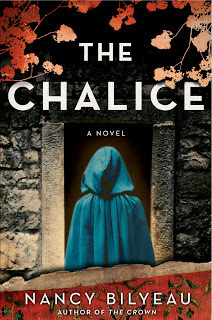

Exclusive Cover Reveal: The Chalice (plus a Giveaway!)

By Nancy Bilyeau

Here, at A Bloody Good Read, a first look at the Touchstone/Simon&Schuster cover for THE CHALICE, the sequel to THE CROWN. This historical thriller continues the adventures of Dominican novice Joanna Stafford in a story that has more twists, higher stakes, and more romance than THE CROWN. As you can see, the mood is EERIE...

This novel, like "The Crown," is based on careful research into the period in English history when Henry VIII ripped the country away from Rome. We've sent the book to some advance readers, and I'd like to share a quote from C.W. Gortner, who wrote the fascinating historical novel "The Queen's Vow: A Novel of Isabella of Castile" as well as the engrossing "The Tudor Secret."

I have another advance copy of THE CHALICE to share before its on-sale date in early March. If you'd like one mailed to you, please comment on the cover that the design team at Touchstone/S&S created.

In the comments to this blog post, tell me what piece of music this cover image evokes for you. And don't forget your email address.

I will pick the winner on Friday, the same day that Scribd.com posts the first two chapters only of THE CHALICE...:)

Here, at A Bloody Good Read, a first look at the Touchstone/Simon&Schuster cover for THE CHALICE, the sequel to THE CROWN. This historical thriller continues the adventures of Dominican novice Joanna Stafford in a story that has more twists, higher stakes, and more romance than THE CROWN. As you can see, the mood is EERIE...

This novel, like "The Crown," is based on careful research into the period in English history when Henry VIII ripped the country away from Rome. We've sent the book to some advance readers, and I'd like to share a quote from C.W. Gortner, who wrote the fascinating historical novel "The Queen's Vow: A Novel of Isabella of Castile" as well as the engrossing "The Tudor Secret."

"Rarely have the terrors of Henry VIII's reformation been so exciting. Court intrigue, bloody executions, and haunting emotional entanglements create a heady brew of mystery and adventure that sweeps us from the devastation of the ransacked cloisters to the dangerous spy centers of London and the Low Countries, as ex-novice Joanna Stafford fights to save her way of life and fulfill an ancient prophecy, before everything she loves is destroyed." -- C.W. Gortner

I have another advance copy of THE CHALICE to share before its on-sale date in early March. If you'd like one mailed to you, please comment on the cover that the design team at Touchstone/S&S created.

In the comments to this blog post, tell me what piece of music this cover image evokes for you. And don't forget your email address.

I will pick the winner on Friday, the same day that Scribd.com posts the first two chapters only of THE CHALICE...:)

Published on November 26, 2012 05:09

November 14, 2012

Bloody Good Interview: Alison Weir

By Nancy Bilyeau

Today I am thrilled to share my interview with not only one of the most successful historians writing today but also a personal hero: Alison Weir. My first Alison Weir book was The Princes in the Tower. It was fascinating--both provocative and convincing. Alison's books are history made compulsively readable; the research is extensive and yet it never, ever dulls the narrative.

One of my favorite aspects of Alison's writing is her shrewd, perceptive and yet deliciously stinging assessment of the major players in English history. I will treat you to her description of queen-to-be Elizabeth Wydville in The Wars of the Roses:

One of my favorite aspects of Alison's writing is her shrewd, perceptive and yet deliciously stinging assessment of the major players in English history. I will treat you to her description of queen-to-be Elizabeth Wydville in The Wars of the Roses:

Alison Weir has written extensively about Tudor and Plantagenet England, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Elizabeth I. When she published The Lady in the Tower in 2009, covering the arrest, trial and execution of Anne Boleyn, I wondered what new perspective she-- or anyone--could possibly bring to this thoroughly written about queen. I had my answer when I came to the last page of the book, moved to tears as I realized as never before how completely abandoned Anne was after her husband rejected her and how difficult it must have been to rally her strength and courage.

Beginning with the the bestseller Innocent Traitor, Alison also writes historical fiction. Her new book is A Dangerous Inheritance: A Novel of Tudor Rivals and the Secret of the Tower. It is the story of two women of history: Kate Plantagenet, illegitimate daughter of Richard III, and Katherine Grey, younger sister of Lady Jane Grey, who was herself imprisoned in the Tower after a secret marriage during the reign of her cousin, Elizabeth I. Not only does the novel bring these women to life with poignant detail but it connects them in surprising--and suspenseful-- ways.

Without further ado...Alison Weir.

Nancy Bilyeau: After I finished A Dangerous Inheritance, I felt disturbed by how lost in their dangerous times these two women were. Was that one of your goals in writing the book, to illuminate how less-well-known women of that age could come to tragedy?

Alison Weir: Yes, it was. I am always interested in retrieving women's histories, and I wanted to show how the constaints of noble birth, royal blood and gender could impact on young girls.

NB: Did you become intrigued by Katherine Grey while researching Lady Jane Grey for your novel and decide then to tell her story as well? And how different she was from her sister!

AW: I became intrigued years ago when I read Two Tudor Portraits by Hester W. Chapman. I wrote Katherine's story in Elizabeth the Queen, but not in any great depth, but I knew enough of it to know that it was a very dramatic tale--and a tragic one. She was very different from Lady Jane Grey; she was beautiful where Jane was plain, placid where Jane was feisty; she was no bluestocking or formidably learned, as Jane was, and in some ways she comes across as lacking in common sense and forethought, but one cannot but feel sympathy for her.

NB: What do you think of the current theory that Frances Brandon was not as abusive to her daughter Jane Grey as historically assumed? Frances was a complex figure in your novel.

AW: I don't buy it! We have Jane's own testimony and other evidence. A historian friend, Nicola Tallis, is writing a biography of Frances, and she believes the traditional view is the correct one--although maybe Henry Grey was even more unpleasant!

NB: Elizabeth I is known to have disliked Katherine Grey and refused to name her heir even before the scandalous marriage and pregnancy. Do you think the dislike was at all justified and would Katherine Grey have made a good queen of England in the 16th century?

AW: Katherine's own behavior--her failure to convert back to the Protestant faith and her flirtations with Spain--was not conducive to Elizabeth thinking kindly of her, but Elizabeth was pretty paranoid about anyone with a claim to the succession, so Katherine was damned from the start. She was pretty and she was younger than the Queen--red flags to a bull!--and she acted very rashly in marrying Edward Seymour. It undermined Elizabeth's policy, threatened her throne, and must have been galling to a queen who rejected marriage for political--and probably psychological--reasons. Katherine did not have what it took to be a queen, neither the brains nor the resolve. She lived in a fantasy world. I can understand why Elizabeth was harsh with her--and in many ways I think it was justified.

NB: How much is known about Richard III's daughter, Kate Plantagenet? Was it more challenging or more interesting to develop her character and plot, since there is less documentation of her life than Katherine Grey's?

AW: Yes, she is mentioned in only four documents--a gift to any novelist, as her life is a blank canvas. But I knew the context of it, as I've studied Richard III's reign over many years. I had to rely on a lot of detective work, inference and probability.

NB: Why did you decide to tell their stories in one book, and not write a book on each of them?

AW: The idea for the book evolved gradually. It was originally going to be based on the premise that Perkin Warbeck really was Richard, Duke of York, but I couldn't make that work, given the source material and the flimsy premise on which he based his claim. I liked the idea of a mystery with a supernatural theme, possibly a timeslip. I wanted to find a new way in which to explore the fate of the Princes in the Tower, and I needed a love story to replace that of Perkin Warbeck and Katherine Gordon. I also wanted to write a sequel to Innocent Traitor. It occurred to me too that writing about Richard III from the point of view of the daughter who loved him would be a novel approach. Eventually, all these ideas came together--and after many nights spent lying awake wondering how to meld them!

NB: The character and actions of Richard III loom large in this book. He fascinates, if not obsesses, people of that time. And couldn't it be argued, with the archaeological dig in Leicester, that he fasciantes us today? Why is that?

AW: People love a mystery, and they also love conspiracy theories. Yes, Richard fascinates--and many become obsessed, which concerns me. As a historian, I feel I must be objective and not emotionally involved. There is a lot of compelling circumstantial evidence that Richard had the Princes murdered and he was a ruthless operator. If there was convincing evidence to counteract that, I would go with it. But nothing I have read has changed my view.

NB: Do you think that they did indeed discover the body of Richard III this year?

AW: It's too early to say. The body was in the right place, the scoliosis ties in with the (hostile) descriptions of Richard, and the wounds could be consistent with those he received at Bosworth. I await the DNA results eagerly.

NB: Your view of Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort was not positive in the novel. Have you always thought of them in this way or did research for the book form newer evaluations?

AW: Some see Henry VII as a Machiavellian ruler; it's trendy nowadays to view Margaret Beaufort as sinister. Historically, I take a different view, but this was fiction, and they are seen from the point of view of Richard's daughter, so naturally she would find them menacing.

NB: Can you tell us about your next book?

AW: It's a biography of Elizabeth of York, and it's nearly finished. I've really enjoyed this project, and have made some surprising discoveries.

-------------------------------------

Thank you, Alison Weir, for agreeing to this interview, and for more information, go to http://alisonweir.org.uk/

Today I am thrilled to share my interview with not only one of the most successful historians writing today but also a personal hero: Alison Weir. My first Alison Weir book was The Princes in the Tower. It was fascinating--both provocative and convincing. Alison's books are history made compulsively readable; the research is extensive and yet it never, ever dulls the narrative.

One of my favorite aspects of Alison's writing is her shrewd, perceptive and yet deliciously stinging assessment of the major players in English history. I will treat you to her description of queen-to-be Elizabeth Wydville in The Wars of the Roses:

One of my favorite aspects of Alison's writing is her shrewd, perceptive and yet deliciously stinging assessment of the major players in English history. I will treat you to her description of queen-to-be Elizabeth Wydville in The Wars of the Roses:"Elizabeth had once been one of Queen Margaret's ladies, which firmly placed her in the wrong camp to start with. She was of medium height, with a good figure, and she was beautiful, having long gilt-blonde hair and an alluring smile. Edward was oblivious to the fact that she was also calculating, ambitious, devious, greedy, ruthless and arrogant."

Alison Weir has written extensively about Tudor and Plantagenet England, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Elizabeth I. When she published The Lady in the Tower in 2009, covering the arrest, trial and execution of Anne Boleyn, I wondered what new perspective she-- or anyone--could possibly bring to this thoroughly written about queen. I had my answer when I came to the last page of the book, moved to tears as I realized as never before how completely abandoned Anne was after her husband rejected her and how difficult it must have been to rally her strength and courage.

Beginning with the the bestseller Innocent Traitor, Alison also writes historical fiction. Her new book is A Dangerous Inheritance: A Novel of Tudor Rivals and the Secret of the Tower. It is the story of two women of history: Kate Plantagenet, illegitimate daughter of Richard III, and Katherine Grey, younger sister of Lady Jane Grey, who was herself imprisoned in the Tower after a secret marriage during the reign of her cousin, Elizabeth I. Not only does the novel bring these women to life with poignant detail but it connects them in surprising--and suspenseful-- ways.

Without further ado...Alison Weir.

Nancy Bilyeau: After I finished A Dangerous Inheritance, I felt disturbed by how lost in their dangerous times these two women were. Was that one of your goals in writing the book, to illuminate how less-well-known women of that age could come to tragedy?

Alison Weir: Yes, it was. I am always interested in retrieving women's histories, and I wanted to show how the constaints of noble birth, royal blood and gender could impact on young girls.

NB: Did you become intrigued by Katherine Grey while researching Lady Jane Grey for your novel and decide then to tell her story as well? And how different she was from her sister!

AW: I became intrigued years ago when I read Two Tudor Portraits by Hester W. Chapman. I wrote Katherine's story in Elizabeth the Queen, but not in any great depth, but I knew enough of it to know that it was a very dramatic tale--and a tragic one. She was very different from Lady Jane Grey; she was beautiful where Jane was plain, placid where Jane was feisty; she was no bluestocking or formidably learned, as Jane was, and in some ways she comes across as lacking in common sense and forethought, but one cannot but feel sympathy for her.

NB: What do you think of the current theory that Frances Brandon was not as abusive to her daughter Jane Grey as historically assumed? Frances was a complex figure in your novel.

AW: I don't buy it! We have Jane's own testimony and other evidence. A historian friend, Nicola Tallis, is writing a biography of Frances, and she believes the traditional view is the correct one--although maybe Henry Grey was even more unpleasant!

NB: Elizabeth I is known to have disliked Katherine Grey and refused to name her heir even before the scandalous marriage and pregnancy. Do you think the dislike was at all justified and would Katherine Grey have made a good queen of England in the 16th century?

AW: Katherine's own behavior--her failure to convert back to the Protestant faith and her flirtations with Spain--was not conducive to Elizabeth thinking kindly of her, but Elizabeth was pretty paranoid about anyone with a claim to the succession, so Katherine was damned from the start. She was pretty and she was younger than the Queen--red flags to a bull!--and she acted very rashly in marrying Edward Seymour. It undermined Elizabeth's policy, threatened her throne, and must have been galling to a queen who rejected marriage for political--and probably psychological--reasons. Katherine did not have what it took to be a queen, neither the brains nor the resolve. She lived in a fantasy world. I can understand why Elizabeth was harsh with her--and in many ways I think it was justified.

NB: How much is known about Richard III's daughter, Kate Plantagenet? Was it more challenging or more interesting to develop her character and plot, since there is less documentation of her life than Katherine Grey's?

AW: Yes, she is mentioned in only four documents--a gift to any novelist, as her life is a blank canvas. But I knew the context of it, as I've studied Richard III's reign over many years. I had to rely on a lot of detective work, inference and probability.

NB: Why did you decide to tell their stories in one book, and not write a book on each of them?

AW: The idea for the book evolved gradually. It was originally going to be based on the premise that Perkin Warbeck really was Richard, Duke of York, but I couldn't make that work, given the source material and the flimsy premise on which he based his claim. I liked the idea of a mystery with a supernatural theme, possibly a timeslip. I wanted to find a new way in which to explore the fate of the Princes in the Tower, and I needed a love story to replace that of Perkin Warbeck and Katherine Gordon. I also wanted to write a sequel to Innocent Traitor. It occurred to me too that writing about Richard III from the point of view of the daughter who loved him would be a novel approach. Eventually, all these ideas came together--and after many nights spent lying awake wondering how to meld them!

NB: The character and actions of Richard III loom large in this book. He fascinates, if not obsesses, people of that time. And couldn't it be argued, with the archaeological dig in Leicester, that he fasciantes us today? Why is that?

AW: People love a mystery, and they also love conspiracy theories. Yes, Richard fascinates--and many become obsessed, which concerns me. As a historian, I feel I must be objective and not emotionally involved. There is a lot of compelling circumstantial evidence that Richard had the Princes murdered and he was a ruthless operator. If there was convincing evidence to counteract that, I would go with it. But nothing I have read has changed my view.

NB: Do you think that they did indeed discover the body of Richard III this year?

AW: It's too early to say. The body was in the right place, the scoliosis ties in with the (hostile) descriptions of Richard, and the wounds could be consistent with those he received at Bosworth. I await the DNA results eagerly.

NB: Your view of Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort was not positive in the novel. Have you always thought of them in this way or did research for the book form newer evaluations?

AW: Some see Henry VII as a Machiavellian ruler; it's trendy nowadays to view Margaret Beaufort as sinister. Historically, I take a different view, but this was fiction, and they are seen from the point of view of Richard's daughter, so naturally she would find them menacing.

NB: Can you tell us about your next book?

AW: It's a biography of Elizabeth of York, and it's nearly finished. I've really enjoyed this project, and have made some surprising discoveries.

-------------------------------------

Thank you, Alison Weir, for agreeing to this interview, and for more information, go to http://alisonweir.org.uk/

Published on November 14, 2012 05:41

August 27, 2012

How fast can you travel by horse anyway?

How fast could this horse go?While working on my second historical mystery,

From the Charred Remains

, I came across a rather straightforward mystery of my own. How long would it have taken to travel the fifty-plus mile trek from London to Oxford, by horse and carriage, in the mid seventeenth-century?

How fast could this horse go?While working on my second historical mystery,

From the Charred Remains

, I came across a rather straightforward mystery of my own. How long would it have taken to travel the fifty-plus mile trek from London to Oxford, by horse and carriage, in the mid seventeenth-century?I have some faint memory of an equation that claimed distance=rate x speed (and even worse memories of trying to apply that equation). I don’t think that equation works, though, when you don’t know the weight of a cart, the strength of a horse, or the conditions of the roads.

So I had to set some perimeters. I needed the cart (wagon, really) to be able to carry two men and two women, along with two or three barrels or bags of miscellaneous supplies. I needed the journey to take less than a day. The wagon had to be decent, but more serviceable and sturdy, than luxurious. It had to be capable of traversing 50 or so miles of the muddy, unpaved London Road. Similarly, the horses had to be from a hearty stock, and affordable for hire by a journeyman. Not being an equestrian, a farrier, or a blacksmith (okay, let’s face it, I’m not even sure if I’ve ever even been on a horse), this has been a truly puzzling question.

So doing a little digging into the Early English Books Online and a few other primary sources, I first learned what kinds of wagons would have been available to a London tradesman in 1666. Here, I relied mainly on woodcuts to show me pictures of how tradesmen conveyed goods. Hackney carriages were available for hire, but those would not likely have been owned by a tradesman. Coaches (Berlins) were just coming into fashion, out of Germany, but again my tradesman would not have found such a vehicle suitable to his needs or budget.

Wing / 1917:08 As for the horses, I looked to Gervase Markham, a seventeenth-century self-titled “Perfect Horse-man,” who shared his “experienced secrets” on horse care and training. He mentions some different kinds of horses (or perhaps more aptly, the services horses can offer), including the “courier,” the “carter,” the “poulter,” and the “packhorse.”

Wing / 1917:08 As for the horses, I looked to Gervase Markham, a seventeenth-century self-titled “Perfect Horse-man,” who shared his “experienced secrets” on horse care and training. He mentions some different kinds of horses (or perhaps more aptly, the services horses can offer), including the “courier,” the “carter,” the “poulter,” and the “packhorse.” Unfortunately, throughout Markham’s lengthy 200+ pages of advice to the horse-challenged, I could only find one bit of useful information for my purposes. He says: “In journeying, ride moderately the first hour or two, but after according to your occasions. Water before you come to your Inn, if you can possibly; but if you cannot, then give warm water in the Inn, after the Horse hath fed, and is full cooled within, and outwardly dried.” He then went on to say something about applying copious amounts of “dog’s grease” to the horse’s limbs and sinews, but I think I wandered off the page at that point.

Then I needed to find out how fast two horses can even pull a wagon. Throwing my question to the whims of Google yielded an oft-repeated response: a team can travel 4 miles an hour on paved or semi-paved roads. Horses can only travel a few hours at a time; so it looks like my fictional travelers will have to exchange horses several times at various coaching houses along the way.

This would mean it would take my travelers 15 hours to travel from London to Oxford, which is FAR TOO LONG for the purposes of my story. Yet, I've always been extremely scrupulous in my attention to historical details. So my puzzle has resulted in another conundrum—bend the facts to fit my story, or bend my story to fit the facts?

What to do? What to do? What would you do?

Published on August 27, 2012 22:46