Hannah Kate's Blog, page 78

August 13, 2013

Guest Post: Tracy Fahey

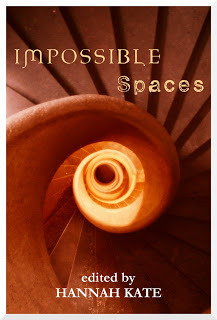

Time for me to invite another writer to come and talk about their work. Following on from Douglas Thompson’s guest post last month, I’m pleased to invite another writer on the Impossible Spaces blog tour onto the site. Today it’s the turn of Tracy Fahey.

I first met Tracy at a conference on monsters and monstrosity that I organized in Manchester in 2012. At that event, she presented some of her academic work which (broadly speaking) falls under the category of ‘Gothic Studies’. I found Tracy’s paper at the conference to be really well-researched and engaging, and so was happy (though surprised – as I had no idea she wrote creatively as well) to see her submit a short story for an anthology I was editing.

I first met Tracy at a conference on monsters and monstrosity that I organized in Manchester in 2012. At that event, she presented some of her academic work which (broadly speaking) falls under the category of ‘Gothic Studies’. I found Tracy’s paper at the conference to be really well-researched and engaging, and so was happy (though surprised – as I had no idea she wrote creatively as well) to see her submit a short story for an anthology I was editing.

Tracy’s story in Impossible Spaces is entitled ‘Looking for Wildgoose Lodge’, and it is a story about the past, about the way we tell stories, and about the way we listen to them and let them shape us. It is a haunting – yet beautiful – piece, and I’m very pleased to have been able to include it in the book. Someone asked Tracy at the launch party why her story was the last one in the collection – if I may, I would like to answer that: I chose ‘Looking for Wildgoose Lodge’ as the finale for Impossible Spaces because it is, at its heart, a story about endings. But it is a story about how an ending just makes us think about all that has come before, all that has led us to that point. Also, the last two sentences gave me goosebumps that didn’t go away for hours, and that seemed a pretty cool way to leave our readers.

Over to Tracy…

Looking for Wildgoose Lodge

My name is Tracy Fahey and I’m a short story addict.

I am also a Gothic researcher who writes about uncanny domestic space, I run an art collective, Gothicise, that re-imagines places, tells stories and makes myths, and I write stories about strange happenings based on odd thoughts, images and fragments of ideas. I’m obsessed with strange sites and stranger stories. For me, short stories are one of the most exquisite forms of writing. The challenge is severe – to create a world in miniature, to set the scene, to draw the characters, to achieve resolution. The great short story writers I admire – Saki, Angela Carter, Guy de Maupassant, Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson – all do this beautifully and make it look effortless. Richard Matheson, damn him, can do it in the space of two pages. Read his grotesque little jewel of a story ‘Born of Man and Woman’ to see precisely how. Sometimes reading so much can actually be off-putting. “Why should I bother writing stories?” you wonder, dismally. “Edgar Allan Poe does it so much better than I ever could!” And perhaps he does. But that’s no reason to quit. For, quite apart from the imagination, we all have an exclusive archive available to us to dip into – our memories.

The stones of Wildgoose Lodge

This story, ‘Looking for Wildgoose Lodge’, slid straight out of the memory vault onto the page. It is (almost) completely true. It’s based on a horrific real-life event, which has been documented in books on history and social history, and fictionalised by William Carleton in one of the great Irish Gothic short stories. It also is a hymn to my late, incomparable grandmother who was a cosy, jumper-knitting, cake-baking archetype of all things grandmotherly. However, she was also fascinated by dark stories, especially local folk tales, and re-told them to me with gusto, with a fine disregard for age-inappropriate content. She continued this interest throughout her life – even after she passed away, we found a scrapbook she’d been keeping on what she called ‘The End Times’, a kaleidoscope of cuttings linked to stories of imminent apocalypse and portents of doom.

That’s one part of the addiction. Dark stories.

The other is my own fascination with impossible spaces. From the cave of inky blackness under the bed, to a crooked alley in a strange town after sunset, to a half-glimpsed shadow flickering at the window of an empty house, the notion of a space where anything could and (and horribly might) happen continues to beguile me. In this story, the contrast between the terrifying drama that had played out in the Lodge and the pitiful handful of stones that remains led me to think about the significance of ruins – as I put it “what remains behind when the story has ended”.

I don’t have a ‘process’ or anything approaching a method when I write short stories (unless you can count endless cups of tea and a tendency to rearrange my bookshelves). Unlike my academic writing, which has to be strictly within the confines of footnotes and references, my creative writing is freedom, untrammelled except by the limits of my imagination. I basically keep a notebook and scribble ideas in it. Most are terrible. Some show promise. Even fewer are finally worked up into stories. That notebook goes everywhere – this year alone it’s been to Berlin, London, Hong Kong and around New Zealand. Travelling, with its ever-changing vistas, strange sights, smells, noises, makes me itch for my pen. ‘Looking for Wildgoose Lodge’ was conceived in Dublin airport, and the first draft was written on the plane to and from the Hobbit premiere in London.

I feel endlessly grateful to have these creative outputs, to make art, to write. The ideas for all my creative projects start on the blank page. I live for the giddy excitement of it all, making the first marks on the white page, the initial, tentative scribbles, and then the fierce flood of black ink as the story takes hold. Nothing else floods me with quite the same feeling of trembling euphoria. It’s compulsive.

My name is Tracy Fahey and I’m a short story addict.

For more information about the Impossible Spaces anthology, or to buy a copy, please visit the Hic Dragones website.

OUT NOW: Impossible Spaces (Hic Dragones, 2013)

edited by Hannah Kate

Blurb:

It doesn’t have to be this way…

Sometimes the rules can change. Sometimes things aren’t how they appear. Sometimes you can just slip through the cracks and end up… somewhere else. What else is there? Is there somewhere else, right beside you, if you could only reach out and touch it? Or is it waiting to reach out and touch you?

Don’t trust what you see. Don’t trust what you hear. Don’t trust what you remember. It isn’t what you think.

A new collection of twenty-one dark, unsettling and weird short stories that explore the spaces at the edge of possibility.

For more information about the book, please visit the publisher’s website.

Contents:

Introduction by Hannah Kate

The Carrier by Daisy Black

Trading Flesh by Simon Bestwick

Etherotopia by Christos Callow Jr.

Mistfall by Jeanette Greaves

The Return of the Curse by Arpa Mukhopadhyay

I’d Lock it with a Zipper by Rachel Yelding

Nepenthes by Keris McDonald

Mindswitch by Chris Galvin Nguyen

Skin Laura Brown

Sharpened Senses by Richard Freeman

The Place of Revelation by Ramsey Campbell

Great Rates, Central Location by Hannah Kate

The Meat House by Maree Kimberley

The Voice Withn by Steven K. Beattie

Shadow by Margrét Helgadóttir

Unfamiliar by Almira Holmes

The Hostel by Nancy Schumann

New Town by Jessica George

Multiplicity by Douglas Thompson

Bruises by Tej Turner

Looking for Wildgoose Lodge by Tracy Fahey

Trailer:

July 18, 2013

Noir Carnival: Circus Music

Charlie was the first one of us as got taken. Not that anyone really noticed at first. It wasn’t easy to tell with Charlie, given that he was bone idle at the best of times. So he if downed tools, there was nothing in it. After a day or so, people started to talk. But it was Charlie, so nothing came of it.

When Len didn’t show to open up shop, people made more of it. There was something as wasn’t right in that. Charlie’s one thing, but Len hasn’t missed a day since his place opened. That should be ‘hadn’t’. Len hadn’t missed a day since his place opened. Save Sundays, of course, but that’s to be expected.

So it shocked us all, truth be told, when we saw that he hadn’t opened up one Monday. When there was no sign of Len in his shop, and he didn’t answer the bell when we rang. After a couple of hours, people started to get a bit worried. Even I did, if I’m honest, though I was never a regular customer of his. Someone suggested going to his house, in case he’d had a fall or some other accident. Someone else tried to get in a look in at the window of the shop’s backroom. ‘Maybe someone’s done for him,’ they said. (I can’t remember who it was.) ‘Maybe he was counting out his money and someone just burst in on him.’

(from my story ‘Idle Hands’ in Noir Carnival, edited by K.A. Laity)

When I first saw the call for submissions for Fox Spirit’s Noir Carnival anthology, I was intrigued. I was fairly certain that it was going to be the sort of book I’d want to read – who can resist the dark attraction of the carnival? – and I had a suspicion it was also the sort of book I wanted to write for. Unfortunately, that suspicion didn’t immediately manifest itself in the form of a brilliant (or original) idea for a story.

But serendipity is a wonderful thing. In March, in a completely unrelated capacity, I attended a conference on ‘Evil and Human Wickedness’ in Lisbon. I was chairing the first panel, and the first paper in that session was presented by a PhD student and musician from the University of Huddersfield, Eleri Ann Evans. In the middle of this paper, Ann discussed some aspects of early twentieth-century circus music, particularly the career of The Brown Brothers. This was my story’s lightbulb moment – though I’m not going to say exactly why, as I don’t want to give away too much of the story!

If you were to think of a circus right now, there are a few images that might pop into your head. I have no doubt you’d imagine a clown – white faced (or, perhaps, black-faced, in ‘burnt cork) and grinning. You might picture a ringmaster – sinister or otherwise – in a red coat and top hat. Maybe you’d picture the tents, the acrobats, the animals. Maybe you’d picture the train filled with performers pulling into a town (or the horse-drawn decorated carts of the ‘mud shows’ that couldn’t afford their own trains). Or perhaps you’d see the sideshows that set up around the big top.

But whatever picture you see when you think of the circus, I bet I have a good chance of guessing what you can hear when you see it.

Admit it. That’s what you could hear.

Everyone knows ‘Entry of the Gladiators’ as the circus song. It’s pervasive and persistent association with the big top is a hint at the important role music has always played in circus performances. The records that survive of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century travelling circuses reveal that music was an integral part of all shows.

When the circus arrived in town – by train or cart – performers would parade through the streets handing out flyers and free tickets. A band would accompany them. When the townsfolk arrived at the tents to watch the show, they’d find a sideshow band amongst the ‘freak shows’ and mini performances around the big top. Every act in the big show would be set to music, and the circus band would exhaust themselves playing throughout the night. When the clowns appeared, they’d often bring their own instruments – the ‘clown band’ was a highlight of many an early circus show – and used their brass and woodwind instruments to produce comical sounds and impressions. For those members of the audience with enough stamina, the circus ‘aftershow’ featured a smaller version of the main band playing a short concert of more ‘serious’ music.

Being a circus musician was no easy gig. Men (and it was almost exclusively men in the early days) who chose this profession were usually expected to play multiple instruments. Due to the varied nature of the programme, lots of different musical arrangements were needed. It would be too expensive for a circus to employ, house and feed a vast orchestra, so they tended to hire players who were versatile. Some performers specialized in strings or woodwind (as these were the more traditional instruments), but the successful ones were the men who could ‘double in brass’ (i.e. they could play the brass instruments that were dominant in the popular clown bands).

One such performer was Tom Brown, who gained fame with his ensemble The Brown Brothers (mostly Tom’s brothers, but occasionally joined by others). This group had played vaudeville – both small-time and big-time – and become known for their versatility, comedy and originality. At some point in the first decade of the twentieth-century they worked with the Guy Brothers circus, but they also worked with the more famous Ringling Brothers as well.

Though the Brown Brothers were able to play a number of instruments, their speciality was the saxophone. These instruments were particularly suited to comedy, and the brothers’ vaudeville act (in which they often performed in burnt cork, oversized shoes, and clothing that would be considered far from politically correct today) showcased the comic potential of the instrument. But in the circus, as in their later career, they revealed their full range. They played ragtime and jazz, music that was ideal for the circus’s late aftershow.

Unlike many of the other saxophone groups around at the same time, The Brown Brothers’ music was recorded on early phonograph technology. And some of these recordings survive, giving us a little glimpse of the circus music created by Tom and his family.

This was the music that was playing in my head (and through my computer) while I was writing ‘Idle Hands’. Just like the audiences of those early shows, I knew the circus had arrived as soon as I heard the band strike up.

(If you’re interested in finding out more about The Brown Brothers and their role in the history of circus and vaudeville music, I highly recommend the book That Moaning Saxophone: The Six Brown Brothers and the Dawning of a Musical Craze by Bruce Vermazen. ‘Idle Hands’ owes a lot to the detailed research in Vermazen’s book.)

Free to Write: Prison Voices

A blog post about creative writing in prisons and the Free to Write book. For more information about Free to Write: Prison Voices Past and Present, please click here. This post is adapted from my (writing as Hannah Priest) chapter in the book.

The first phase of the Free to Write project at Liverpool John Moores University ran from 2004-2007. The book, designed for use by prisoners and writers, marks the second phase of the project. Free to Write grew out of conversations between cultural historians and creative writing practitioners within the university, groups of people who shared common interests in the role of writing within the prison system and in the articulation of prison voices both past and present.

Throughout the twentieth century, prisoners’ access to writing and publication has been varied, to say the least. In the early half of the century, denial or confiscation of writing materials was common in a number of institutions. While the legacy of nineteenth-century reformers like Elizabeth Fry and Sarah Martin was still felt, particularly as regards reading habits and literacy, prisoners were not always encouraged towards any creative endeavours of their own.

While no doubt many prisoners at this time managed to write – letters, poems or memoirs – few examples of prison writing were published and shared with members of society outside prison walls. There were, of course, exceptions to this, and one notable example, W.F.R. Macartney’s autobiographical account of life in Parkhurst entitled Walls Have Mouths (1936), implied a relationship between the way prisoners are perceived and a denial of prisoners’ writing. Macartney wrote that ‘the convict is treated unnaturally: he […] must not speak’. As can be seen from the title of his memoir, as well as from its contents, Macartney felt that there was something inherently wrong with this closing of prisoners’ ‘mouths’. His writing was an act of speech, an act of regaining his own voice and asking others to listen to it.

Historical instances of prisoner writing raise some important questions for a contemporary creative writing project. Why is freedom to write necessary for prisoners? How does this benefit someone within the prison system? How can a prisoner’s ‘voice’ help their rehabilitation? And how will this benefit society as a whole? Understanding the answers to these questions has been of central concern to prisoner writing projects from the 1960s onwards, as they were – though perhaps expressed somewhat differently – for earlier prison reformers and educators.

In 1962 Arthur Koestler founded an award scheme for prisoner writing and artwork. Originally planned as an award for essay writing, the Koestler awards were intended to reward creative, productive activity. Himself a former political prisoner, Koestler was a firm believer in the positive impact of mental stimulation on a prisoner’s wellbeing and rehabilitation. He viewed boredom as the main ‘enemy’ of the prisoner, and he predicted that counteracting this would become even more vital when (as he rightly anticipated) the abolition of the death penalty lead to an increase in prisoners serving life-tariffs. Koestler’s championing of intellectual activity for prisoners is reminiscent of the work of prison reformers Fry and Martin: stimulation of the mind and the pursuit of ‘higher’ things are encouraged as a way to transcend both the reality of imprisonment and the circumstances which may have led to it.

However, while Koestler’s original focus was intellectual and academic stimulation, his legacy is somewhat broader. At the time of writing, the Koestler award scheme has just passed its fiftieth birthday and now offers awards for work in the visual arts and creative writing, as well as mentor programmes, exhibitions and sale of prisoner art. Like many organisations working in this field, the Koestler Trust recognise and promote the need for prisoner creativity – beyond mental stimulation or productivity – as a means of recovery, rehabilitation and understanding.

By the 1970s, the therapeutic benefits of prisoner life-writing were beginning to be recognised. In his history of British prison writing, Julian Broadhead notes that, unlike many earlier autobiographers, Jimmy Boyle was able to write A Sense of Freedom (1977) ‘without hindrance or concern that his manuscript would be confiscated’ during his time in the Barlinnie Special Unit. Just under a decade later, the UK prison system’s first writer-in-residence, Tom Hadaway, took up a post at HMP Durham, a placement co-funded by the WRVS, Northern Arts and the Arts Council.

The introduction of a writer-in-residence to a prison signalled a clear recognition of creativity as a beneficial practice for prisoners, prisons and the wider public. While education services provided – and continue to provide – valuable literacy and reading skills, a writer in a prison offers something rather different. Writer-in-residence programmes developed further in the years following Hadaway’s appointment, with the Writers in Residence in Prison Scheme being set up in 1992 by the Arts Council of England and the Home Office to offer placements for writers in various institutions throughout the United Kingdom. In 1998, the Writers in Prisons Network was appointed by the Arts Council to administer this scheme in recognition of the ‘ongoing needs of prisons, writers and inmates involved in residencies’.

The past couple of decades have seen an increase in the number of creative professionals working in prisons, but also a dramatic increase in the number of outlets for publication and performance of prisoners’ creative writing. It is certainly true that, for as long as there have been prisons, there have been writers producing work within their walls: Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur may be one of the earliest examples, but John Bunyon’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis are perhaps more well-known as seminal works of English Literature produced inside a prison. A number of prison memoirs were published during the twentieth century, the number dramatically increasing in the later decades, although it should be noted that the majority of these were published after the writer’s release. However, interest in and outlets for poetry, fiction and other creative writing by those still within the prison system were (and, to an extent, still are) limited. An important aspect of many twenty-first century projects is the dissemination of prisoners’ work, either through print publication or performance.

Prisoners’ access to publication is a legal, moral and practical battleground, with equally vocal challengers and supporters. For every high-profile case of an individual publishing and profiting from work produced while serving a sentence – for example, Jeffrey Archer’s publication of his Prison Diaries – there is an equally high-profile case of a prisoner being denied the opportunity to release autobiographical material – as in the High Court’s ruling that the confiscation of Denis Nilsen’s autobiography by staff at HMP Full Sutton must stand to prevent Nilsen’s intended publication of the book.

Nevertheless, a significant number of contemporary writing projects have worked with publication as an ultimate goal and a number of anthologies of prisoner writing have been produced as a result. Indeed, the Free to Write collection itself is one such anthology, including as it does examples of creative writing written in UK prisons. In addition to this, local magazines produced for and by prisoners in individual institutions have been encouraged and supported by writers-in-residence and education staff, and national magazines such as Inside Time and Women in Prison offer further avenues for publication of creative writing and letters. Considering the intended impact and benefit of such outlets reveals an awareness of the rehabilitative and reflective potency of creative expression, but also significant connection with much earlier publications such as the American journal Star of Hope.

The full text of this article can be found in Free to Write: Prison Voices Past and Present, edited by Gareth Creer, Hannah Priest and Tamsin Spargo (Headland, 2013)

OUT NOW: Free to Write: Prison Voices Past and Present (Headland)

Okay, so despite this blog supposedly just being for my creative work, I thought I’d mention a book I’ve been involved in as an academic. (I know I keep doing this, but I can’t seem to keep my two personas separate at the moment!)

Free to Write: Prison Voices Past and Present is an anthology of essays and creative writing that has grown out of a research project at Liverpool John Moores University. The first section of the book contains essays about the history of creative writing in prisons, and the second section showcases original writing from individuals within the UK prison system (with a commentary by Adam Creed). Writing as Hannah Priest, I contributed an essay for the first section, and I was one of the editors of the book along with Gareth Creer and Tamsin Spargo. I’ll post something longer about my own essay in the book later this week. But, for now, I’ll just present the book itself.

Free to Write: Prison Voices Past and Present

Foreword by Erwin James

Edited by Gareth Creer, Hannah Priest and Tamsin Spargo

Blurb:

“The Free to Write Project has demonstrated that the long, rich and resilient tradition of writing in prison is as vital and vibrant as ever. The poems and narratives withing these pages tell us of lives that are valuable and resilient.” – Erwin James

Free to Write introduces new writing by prisoners as well as true stories of how writing helped men and women of the past imagine a better future after prison.

It is the outcome of a practical research project run by Liverpool John Moores University’s Centre for Writing and Research Centre for Literature and Cultural History.

Essays by Tamsin Spargo, Helen Rogers, Hannah Priest and Adam Creed.

Poetry and prose from HMP Shrewsbury, HMP Frankland, HMP Styal, HMP Lancaster Farms and HMP Greenock.

Contents:

Editors’ Note by Gareth Creer, Hannah Priest and Tamsin Spargo

Foreword by Erwin James

Free to Learn? Reading and Writing in the Early Nineteenth-Century Prison by Helen Rogers

Mountain Bughouse 216: One Prisoner’s Writing as Protest and Escape by Tamsin Spargo

Free to Write: Prison Voices by Hannah Priest

Prison Voices: Present (Poetry and prose from HMP Shrewsbury, HMP Frankland, HMP Styal, HMP Lancaster Farms and HMP Greenock with commentary by Adam Creed)

For more information about the book, please contact the publisher.

July 17, 2013

OUT NOW: Noir Carnival (Fox Spirit Books)

Edited by K.A. Laity

Carnival: whether you picture it as a traveling fair in the back roads of America or the hedonistic nights of the pre-Lenten festival where masks hide faces while the skin glories in its revelation. It’s about spectacle, artificiality and the things we hide behind the greasepaint or the tent flap.

Let these writers lead you on a journey into that heart of blackened darkness and show you what’s behind the glitz.

Underneath, we’re all freaks after all…

Contents:

Caravan: A Preamble by K.A. Laity

Family Blessings by Jan Kozlowski

In the Mouth of the Beast by Li Huijia

Idle Hands by Hannah Kate

The Things We Leave Behind by Christopher L. Irvin

She’s My Witch by Paul D. Brazill

The Mermaid Illusion by Carol Borden

Natural Flavoring by Rebecca Snow

Madam Mafoutee’s Bad Glass Eye by Chloe Yates

Buffalo Brendan and the Big Top Ballot by Allan Watson

Carne Levare by Emma Teichmann

Leave No Trace by A.J. Sikes

Fair by Robin Wyatt Dunn

Things Happen Here After Dark by Sheri White

Mister Know It All by Richard Godwin

Trapped by Joan De La Haye

The Price of Admission by Neal F. Litherland

Take Your Chances by Michael S. Chong

Mooncalf by Katie Young

The Teeth Behind the Beard by James Bennett

For more information, please visit the Fox Spirit website.

July 15, 2013

Impossible Spaces Book Trailer

The video trailer for Impossible Spaces, published by Hic Dragones and edited by me! The music, written especially for the trailer, is by the awesome Digital Front.

The book is out on Friday July 19th. Check out the publishers’ website for more information.

Guest Post: Douglas Thompson

It’s always difficult to think of things to blog about, so I thought it would liven things up a bit if I invited some authors to guest post for me. I’ll be inviting a number of guests over the next couple of months, all of whom are excellent writers whose work I really enjoy. Today’s post is the inaugural post in the Impossible Spaces blog tour, which will visit a number of blogs and feature some of the writers in the new short story collection from Hic Dragones (which happens to have been edited by yours truly).

So, that introduction over, I’m pleased to introduce today’s guest blogger, Douglas Thompson. As well as numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, Douglas is the author of seven novels: Ultrameta (2009) and Sylvow (2010) both from Eibonvale Press, Apoidea (2011) from The Exaggerated Press, Mechagnosis from Dog Horn (2012), Entanglement from Elsewhen Press ( 2012), and Volwys and Freasdal from Dog Horn and Acair Publishing respectively, due in late 2013/early 2014. You can find Douglas on Twitter as @UrbanSurrealist.

So, that introduction over, I’m pleased to introduce today’s guest blogger, Douglas Thompson. As well as numerous short stories in magazines and anthologies, Douglas is the author of seven novels: Ultrameta (2009) and Sylvow (2010) both from Eibonvale Press, Apoidea (2011) from The Exaggerated Press, Mechagnosis from Dog Horn (2012), Entanglement from Elsewhen Press ( 2012), and Volwys and Freasdal from Dog Horn and Acair Publishing respectively, due in late 2013/early 2014. You can find Douglas on Twitter as @UrbanSurrealist.

Douglas’s story for Impossible Spaces is entitled ‘Multiplicity’, and I was struck straightaway by both the subject matter and the author’s voice. It’s a strange tale – a piece of science fiction – but it offers such a compelling ‘what if’ conundrum that it encourages (as the best science fiction always does) the reader to look beyond the futuristic setting and advanced technology, and to see the people behind this. I could wax lyrical about the questions and ideas raised by Douglas’s story, and by the offbeat way he weaves his tale, but I think I’ll let the author do the rest of the talking!

Multiplicity

Firstly, I want to thank Hannah Kate for all her hard work in editing this story. Over the years I’ve come to enjoy the cut and thrust of the editorial phase, and even when (maybe especially when!) things get heated, the result is usually a better story. New writers starting out need to understand that, despite its lonely image, writing is a form of social exchange like so many others which go to make up our society. The irony of this often hits me when I find myself reading and performing my work: how the introverted boy writing away in his teenage attic has somehow eventually found himself having to read out his most personal thoughts to a room full of strangers… and nobody even forced him into it! Life is often like this: in the end it turns us all around to face the opposite way from how we started out.

As well as being one of the stories in the brilliantly-themed Impossible Spaces anthology (for which I wrote it specifically), ‘Multiplicity’ is one of ten stories that will be published in my seventh book, Volwys & Other Stories, by Dog Horn in late 2013/early 2014. All the stories in the collection are more or less science fiction, some near future, others (like ‘Multiplicity’) set far into a technologically advanced future. Most of the stories are also united by a kind of apocalyptic bent, in which I deconstruct humanity or society in one way or another. I never thought I’d end up writing science fiction, and indeed after this collection I will probably head away from it again, back to the kind of mainstream literary fiction I started out writing back in 1990. Then again, Ray Bradbury was one of my first influences as a kid, so maybe life moves in circles. Actually, I don’t believe in boundary genres much. In fact, I’m kind of dedicating my life to trying to destroy them, other than my own personal genre category, which is ‘surreal’. I feel I kind of own that one (and the domain name ‘Glasgow Surrealist’), since my brother is a neo-surrealist artist and I grew up immersed in his influence (he is 12 years older than me, us being the eldest and youngest of 4 children).

One of my favourite questions I like to use to confront genre fans, and literary snobs prejudiced against genres, is this one: what genre is your life? A supernatural ghost story when a close relative dies, a horror story in the traffic jam to work in the morning, a tragi-comedy at work, and, if you’re very lucky, hardcore porn once a week? My point is that life defies genre categories of course, or rather involves all of them at once, and therefore so should good fiction. Although I hope my writing is entertaining, my primary aim is never to entertain people so much as to make them think. I’d say our over-stimulated contemporary world is drowning in entertainment right now, but I don’t see much evidence of it drowning in thought or self-analysis when I turn on the evening news and watch the general mayhem. I always have a picture in my head of those grey aliens dashing home from work every night to watch ‘Earth Tonight’ and holding their little sides as they howl with laughter at all our murderous stupidity and wasteful disrespect towards the beautiful planet we’ve been given. Coupled with this, I have another image of a signboard posted up just outside our solar system which says ‘Approaching Earth, sense of humour essential’.

The problem with life of course, is that we’re so close to it that we can’t see it clearly enough to make sense of it. We are ‘immured’ to it, meaning that familiarity has built an invisible wall in our minds between ourselves and reality. This is a deadly kind of sleepwalking. I’d say over 80% of human beings are sleepwalking. The beauty of science fiction and all kinds of ‘speculative fiction’ is that they enable the writer to wake themselves and the readers up. This is done by showing the reader what they think at first is an alternative reality, something safely different to their own. Then later on, towards the end usually, you can pull the rug away and make them realise that it’s reality they’ve been looking at all along, just viewed through a distorting mirror. It’s the only way to get around our inherent blindness. The problem in much ‘literary’ fiction is that it fails this test. By merely showing people the world they think they know, the tyranny of the mundane is reinforced along with the insidious notion that it is a reality hard to change. I passionately believe that human beings can and must change their world, or more specifically their behaviour, in major ways, through cooperation and debate. Good science fiction (which is thin on the ground these days, and generally isn’t the stuff that wins the awards) is about the manifestos of these possible futures, and seen like that they are politically important, not just the reading fodder of spotty youths. We need to remember that Orwell’s 1984 was science fiction, as was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Pure sociology and politics.

The problem with life of course, is that we’re so close to it that we can’t see it clearly enough to make sense of it. We are ‘immured’ to it, meaning that familiarity has built an invisible wall in our minds between ourselves and reality. This is a deadly kind of sleepwalking. I’d say over 80% of human beings are sleepwalking. The beauty of science fiction and all kinds of ‘speculative fiction’ is that they enable the writer to wake themselves and the readers up. This is done by showing the reader what they think at first is an alternative reality, something safely different to their own. Then later on, towards the end usually, you can pull the rug away and make them realise that it’s reality they’ve been looking at all along, just viewed through a distorting mirror. It’s the only way to get around our inherent blindness. The problem in much ‘literary’ fiction is that it fails this test. By merely showing people the world they think they know, the tyranny of the mundane is reinforced along with the insidious notion that it is a reality hard to change. I passionately believe that human beings can and must change their world, or more specifically their behaviour, in major ways, through cooperation and debate. Good science fiction (which is thin on the ground these days, and generally isn’t the stuff that wins the awards) is about the manifestos of these possible futures, and seen like that they are politically important, not just the reading fodder of spotty youths. We need to remember that Orwell’s 1984 was science fiction, as was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Pure sociology and politics.

In ‘Multiplicity’ I show a weird side-effect of a black hole generating multiple versions of people ageing and de-ageing at different rates, and ‘polluting’ their genes with those of other people. But these apparently exotic devices are really only the writer’s tricks to make the reader see themselves as they really are. ‘Ordinary’ life is actually utterly exotic, if we could only see it that way. Human reproduction is inevitably the ‘pollution’ of our genes, except that this is a wonderful thing which keeps our species healthy and enables us to adapt through evolution. Dying and giving birth, although terrifying and miraculous when seen in the accelerated timescale of the story, are utterly essential and completely interlinked with our sexual method of evolution. Death and individuality seem at odds with our sense of who we are in the world (‘how can I be so totally extinguished while others go on living?’), so there are clues there to a new way in which we need to see ourselves in order to make sense of our place in the universe: not as mortal individuals at all, but as an immortal group consciousness. This is my future manifesto, and socio-political proposition.

For more information about the Impossible Spaces anthology, or to buy a copy, please visit the Hic Dragones website.

June 18, 2013

Impossible Spaces Launch Party

Friday 19 July, 7.00-9.00pm

Free entry

International Anthony Burgess Foundation

3 Cambridge Street

Manchester M1 5BY

United Kingdom

Join us at the launch of Impossible Spaces, a new collection of short stories from Hic Dragones.

Sometimes the rules can change. Sometimes things aren’t how they appear. Sometimes you can just slip through the cracks and end up… somewhere else. What else is there? Is there somewhere else, right beside you, if you could only reach out and touch it? Or is it waiting to reach out and touch you?

Don’t trust what you see. Don’t trust what you hear. Don’t trust what you remember. It isn’t what you think.

A new collection of twenty-one dark, unsettling and weird short stories that explore the spaces at the edge of possibility. Stories by: Ramsey Campbell, Simon Bestwick, Hannah Kate, Jeanette Greaves, Richard Freeman, Almira Holmes, Arpa Mukhopadhyay, Chris Galvin Nguyen, Christos Callow Jr., Daisy Black, Douglas Thompson, Jessica George, Keris McDonald, Laura Brown, Maree Kimberley, Margret Helgadottir, Nancy Schumann, Rachel Yelding, Steven K. Beattie, Tej Turner and Tracy Fahey.

Free event, with wine reception from 7pm. Readings from Douglas Thompson, Rachel Yelding, Tracy Fahey, Jeanette Greaves, Nancy Schumann, Jessica George and Hannah Kate. Launch party discount on book sales and competition/giveaways.

Sell Tickets Online through Eventbrite

April 22, 2013

Hic Dragones presents… A Night of Strange and Dark Fictions

as part of Prestwich Book Festival

Monday 27th May, 7.30pm

Prestwich British Legion (near Heaton Park tram station)

225 Bury Old Road

Prestwich M25 1JE

Tickets £6 (+ booking fee) in advance from the festival’s Eventbrite shop

Come and listen to some of the finest and strangest authors writing in the UK today. What do they have in common? They’ve all been published – at one stage or another – by North Manchester’s strangest publishing house, Hic Dragones. And they’re together in Prestwich for one night only.

Come and listen to some of the finest and strangest authors writing in the UK today. What do they have in common? They’ve all been published – at one stage or another – by North Manchester’s strangest publishing house, Hic Dragones. And they’re together in Prestwich for one night only.

Rosie Garland

Rosie Garland

Manchester-based Rosie Garland has published five solo collections of poetry and her award-winning short stories, poems and essays have been widely anthologized. She is an eclectic writer and performer, ranging from singing in Goth band The March Violets to her well-loved stage persona Rosie Lugosi the Vampire Queen. The Palace of Curiosities (HarperCollins) is her debut novel.

Toby Stone

Toby Stone

Toby Stone is a Whitefield-based novelist who also teaches in North Manchester. Toby went to the same school as Batman (Christian Bale) and Benny Hill. As an adult, Toby has been a toy-seller, an Avon lady, double-glazing Salesman of the Week, a mortgage broker, a suspicious barman, a school governor and a bingo caller. Aimee and the Bear (Hic Dragones) is his first novel.

Also featuring readings from Hic Dragones anthology writers:

Simon Bestwick: acclaimed author of ‘modern masterpiece of horror’ The Faceless (Solaris)

Richard Freeman: writer and cryptozoologist

Jeanette Greaves: contributor to Wolf-Girls and Impossible Spaces

Nancy Schumann: author of Take a Bite, a history of female vampires in folklore and literature

Beth Daley: graduate of the Creative Writing PhD programme at the University of Manchester

Daisy Black: writer, medievalist and heavy metal morris dancer

Your host for the evening will be Hannah Kate, ringmaster at the strange little circus that is Hic Dragones.

Plus… prizes to be won, a bookstall and a stall from Rock and Goth Plus

powered by