Balogun Ojetade's Blog, page 27

April 15, 2013

THE ROAD TO NICODEMUS: Black Towns in the Age of Steam!

THE ROAD TO NICODEMUS: Black Towns in the Age of Steam!

Black Americans have played a vital role in building this nation. Eager to live and prosper as free people, we have established our own towns since Colonial times. Many of these communities were destroyed by racial violence or injustice, while some just died out. Let’s explore a few of these symbols of freedom, courage, hard work and ingenuity a bit more in-depth.

Fort Mose, Florida

Although this settlement was established well before the Age of Steam, it still merits mentioning, as it is a fascinating place with an even more fascinating history. Established in 1738, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose – or Fort Mose – was the first free black settlement in what is now the United States and played an important role in the development of colonial North America.

Although this settlement was established well before the Age of Steam, it still merits mentioning, as it is a fascinating place with an even more fascinating history. Established in 1738, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose – or Fort Mose – was the first free black settlement in what is now the United States and played an important role in the development of colonial North America.

Amid the fight for control of the New World, Great Britain, Spain and other European nations relied on African slave labor. Exploiting its proximity to plantations in the British colonies in North America and the West Indies, King Charles II, of Spain issued the Edict of 1693 which stated that any male slave on an English plantation who escaped to Spanish Florida would be granted freedom, provided he joined the Militia and became a Catholic. This edict became one of the New World’s earliest emancipation proclamations.

By 1738 there were 100 Black men, mostly runaways from the Carolinas, living in what became Fort Mose. Many were skilled workers, blacksmiths, carpenters, cattlemen, boatmen, and farmers. With accompanying women and children, they created a colony of freed people that ultimately attracted other fugitive slaves.

When war broke out in 1740 between England and Spain, the people of St. Augustine and nearby Fort Mose found themselves involved in a conflict that stretched across three continents. The English sent thousands of soldiers and dozens of ships to destroy St. Augustine and bring back any runaways. They set up a blockade and bombarded the town for 27 consecutive days. Hopelessly outnumbered, the diverse population of blacks, First Nation peoples and whites pulled together. Fort Mose was one of the first places attacked. Lead by Captain Francisco Menendez, the men of the Fort Mose Militia briefly lost the Fort but eventually recaptured it, repelling the English invasion force. Florida remained in Spanish hands and for the next 80 years remained a haven for fugitive slaves from the British colonial possessions of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

The site was abandoned in 1763 when the British took possession of Florida. The residents of Mose evacuated to Cuba and formed a new town, Ceiba Mocha, Matanzas province, considered the hub of African spirituality in Cuba.

Rosewood, Florida

Rosewood – taking its name from the abundant red cedar that grew in the area – was established in 1870.

Rosewood – taking its name from the abundant red cedar that grew in the area – was established in 1870.

The town prospered as the Florida Railroad established a small depot to handle the transport of cedar wood to the pencil factory in Cedar Key and the transportation of timber, turpentine rosin, citrus, vegetables, and cotton throughout the State. In 1890 the cedar depleted and many of the white families moved to Sumner, three miles west of Rosewood and worked at the newfound saw mill established by Cummer and Sons. By 1900 Rosewood had a black majority of citizens.

On the morning of January 1, 1923 Fannie Coleman Taylor of Sumner Florida, claimed she was assaulted by a Black man. Although she was supposedly knocked unconscious for several hours due to the shock of the incident, she was not seriously injured and was miraculously able to describe, in detail, what happened. No one disputed her account, of course and no questions were asked. It was assumed she was reporting the incident accurately.

Sarah Carrier a Black woman from Rosewood, who did the laundry for Fannie Taylor and was present on the morning of the incident, claimed the man that assaulted Fannie Taylor was her white lover. It was believed the two lovers quarreled and he abused Fannie and left. However, in 1923 no one questioned Fannie Taylor’s account and no one asked Sarah Carrier about the incident. The Black community claimed Fannie Taylor was only protecting herself from scandal.

A posse was summoned and tracking dogs were ordered by James Taylor, Fannie Taylor’s husband and the foreman at Cummer and Sons saw mill. The local white community became enraged at the alleged abuse of a white woman by a Black man – an unpardonable sin in a world in which it was punishable for black men back then to even look at a white woman.

James Taylor summoned help from Levy County and neighboring Alachua County, where a large number of KKK members had been rallying and marching in opposition of justice for Black people.

A telegraph sent to Gainesville in regards to Fannie Taylor’s allegations provoked four to five hundred Klansmen, who headed to Sumner at the appeal of James Taylor. They arrived enraged and combed the woods behind the Taylor’s home looking for a suspect. Suspicion soon fell on Jesse Hunter, a Black man who had allegedly recently escaped from a convict road gang. No proof of the escape was ever provided.

The posse confronted Sam Carter at his home and Carter allegedly admitted to helping Hunter escape. The posse forced Carter to take them to the place where he last saw Hunter. When no trace of Hunter could be found the posse turned into an out of control lynch mob, torturing Carter, riddling him with bullets and hanging him from a tree.

The posse continued their hunt in Rosewood. They found Aaron Carrier, cousin and friend to Sam Carter, in bed at his cousin, Sarah Carrier’s house. They yanked him out of bed, tied a rope around his neck and dragged him behind a Model –T Ford from Rosewood to Sumner. They tortured him, beat him with gun butts and kicked him until he lost consciousness they then shot him numerous times.

Levy County Sherriff Bob Walker halted the gunfire before a fatal shot could be delivered, however, when he yelled, “Don’t, I’ll finish the nigger off!” Confident that the sheriff would take care of Aaron Carrier, the posse returned to Rosewood to hunt and kill more Black people.

Sheriff Walker threw Aaron Carrier in his vehicle and took him to Gainesville, to the Alachua County jail, begging Sheriff James Ramsey to hide Carrier from the public and his family until tempers settled down. Sheriff Walker also suggested that Sheriff Ramsey get medical help for Carrier. Sheriff Ramsey brought in two local Black doctors – Dr. Parker and Dr. Ayers – to treat Carrier. For six months, without any knowledge of the public or Carrier’s family, the doctors tending to Carrier’s wounds and returned him to health and strength.

Fuming with anger because they had not found the attacker James Taylor sent Sarah Carrier’s son, Sylvester Carrier, a message “We are coming to get you.”

Unbeknownst to the posse, Sylvester Carrier took heed to the threats and made contact with his Levy County friends who bravely traveled to Rosewood to help avert the planned ambush of its citizens.

After dark, the white posse traveled to Rosewood prepared to kill or be killed. The posse, intoxicated with moonshine and ignorance, was met head-on with resistance from Sylvester Carrier and his friends, however and several of them were killed or injured. The surviving posse members fled, returning to Sumner, leaving their guns behind at the order of Sylvester Carrier and his men. Other posse members lay dead and wounded in Sarah Carrier’s yard.

On January 3rd, many citizens of Rosewood fled into the swamp, hiding out and waiting for the train to come and take them to safety. Others fled to white store merchant John Wright’s home. He allowed them to wait there in hiding until they heard back from Sheriff Walker, who travelled back and forth to Cedar Key, Sumner, and Rosewood in an effort to move Rosewood’s citizens safely out of Rosewood on the 4 AM early morning train, which was conducted by the Bryce Brothers from Bryceville, Florida.

When the posse returned to Rosewood days later to make an assessment of the damages, they vengefully shot and killed anyone who remained in the town – mainly those too ill or too old to

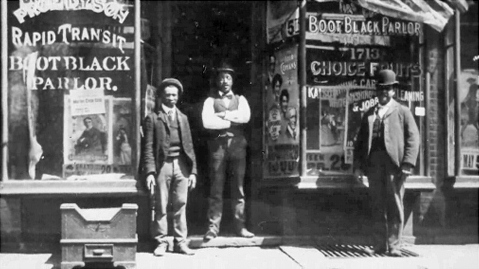

Weeksville, New York

What is now Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, NY, Weeksville was the second-largest community for free blacks prior to the Civil War. James Weeks, a freed slave, purchased a significant amount of land from Henry C. Thompson, another freed slave. Weeks sold property to new residents, who eventually named the community after him. The town thrived, becoming a free Black enclave of urban trades-people and property owners comprised of both Southern blacks fleeing slavery and Northern blacks escaping the racial violence and draft riots in New York and other cities. By the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, Weeksville was already a thriving area with its own doctors, teachers, publishers, and social services.

What is now Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, NY, Weeksville was the second-largest community for free blacks prior to the Civil War. James Weeks, a freed slave, purchased a significant amount of land from Henry C. Thompson, another freed slave. Weeks sold property to new residents, who eventually named the community after him. The town thrived, becoming a free Black enclave of urban trades-people and property owners comprised of both Southern blacks fleeing slavery and Northern blacks escaping the racial violence and draft riots in New York and other cities. By the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, Weeksville was already a thriving area with its own doctors, teachers, publishers, and social services.

My Steamfunk fable, Seeking Shelter, is set in Weeksville.

Freedmen’s Town, Texas: Houston’s ‘Little Harlem’

Immediately following the Civil War, thousands of freed slaves purchased land and built their homes along the Buffalo Bayou, dubbing the area “Freedmen’s Town.”

Immediately following the Civil War, thousands of freed slaves purchased land and built their homes along the Buffalo Bayou, dubbing the area “Freedmen’s Town.”

Over a period of sixty years the town thrived, with churches, schools, stores, theaters and jazz spots lining the cobblestone roadways, earning Freedmen’s Town the nickname of “Little Harlem” by the 1920s.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression caused many residents of Freedmen’s Town to lose their homes. Most longtime residents were forced to move to other Houston neighborhoods, while others stayed in the town, only to watch the community deteriorate.

In 1984, Freedmen’s was designated a historic district.

Blackdom, New Mexico

Dispatched from Ft. Leavenworth for the New Mexico Territory in 1846 to fight the Mexican-American War, General Stephen W. Kearny led a force of 2,500 soldiers in the invasion (yes, invasion – just ask the First Nations in the area). One of those detailed to that force as a wagoneer was a Georgia freedman by the name of Henry Boyer. Upon reaching New Mexico, Boyer fell in love with the vast desert expanses of sky and land, upon his return home, he told his wife and children tales of his adventures in New Mexico, emphasizing the awesome beauty of the land.

Dispatched from Ft. Leavenworth for the New Mexico Territory in 1846 to fight the Mexican-American War, General Stephen W. Kearny led a force of 2,500 soldiers in the invasion (yes, invasion – just ask the First Nations in the area). One of those detailed to that force as a wagoneer was a Georgia freedman by the name of Henry Boyer. Upon reaching New Mexico, Boyer fell in love with the vast desert expanses of sky and land, upon his return home, he told his wife and children tales of his adventures in New Mexico, emphasizing the awesome beauty of the land.

One of Boyer’s children, Francis Marion (“Frank”) Boyer, was captivated by his father’s stories. Frank, a graduate of Morehouse College and a teacher, grew dissatisfied with his existence in Georgia and joined groups of other Black men who spoke out against the savageries of the Ku Klux Klan and other Southern atrocities.

Fearing for his son’s life, Henry Boyer suggested that Frank leave Georgia and move to New Mexico to seek a better life for himself and his family. In 1896, Frank Boyer and his friend and student, Daniel Keyes, decided to set out for New Mexico.

Being Black, Mr. Boyer and Mr. Keyes could not travel by stagecoach or rail, nor could they get secure passage on a wagon train. Undeterred, they set out on foot, and walked the entire distance from Pellum (nowadays known as “Pelham”), Georgia to Roswell, New Mexico – a distance of 1,200 miles.

Upon arrival, the two men worked multiple jobs while exercising their rights as freedmen under the Homestead Act, laying claim to acreage in the area of what is now Dexter. The following year, Franks’s wife, Ella Louise and their children joined him, and he was able to secure a loan from a bank to begin homesteading. He dug an artesian well, built a house, and began an active outreach campaign to other Black families in surrounding states, urging them to come to the beautiful desert land in the southeastern part of the Territory and help create the New Mexico Territory’s first Black community.

And they came…more than 300 people from across the country…despite the odds; despite the obstacles. Whites would not sell them train or stagecoach tickets and would not permit them to board in the event that they managed to secure tickets anyway; they would not sell wagons or horses to Black families, despite their ability to pay.

But they came…by cart; on horseback; on foot like the town’s founders…and in 1903, Frank Boyer filed the town of Blackdom’s articles of incorporation.

Unfortunately, in the 1920s, a severe drought led settlers to abandon the town.

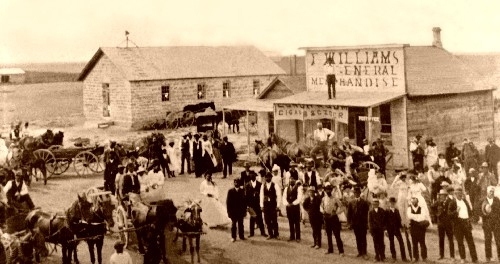

Nicodemus, Kansas

Nicodemus, Kansas is the only remaining western community established by African Americans after the Civil War. The town is now recognized as a National Historic Site.

Nicodemus, Kansas is the only remaining western community established by African Americans after the Civil War. The town is now recognized as a National Historic Site.

In the late 1870’s, as the Reconstruction following the Civil War failed to bring the long awaited freedom, equality and prosperity promised to Black people, along came a white man by the name of W.R. Hill – to black families in the backwoods of Kentucky and Tennessee – who described a “Promise Land” in Kansas. Hill told of a sparsely settled territory with abundant wild game, wild horses that could be tamed, and an opportunity to own land through the homesteading process in Nicodemus, Kansas.

The town site of Nicodemus was planned in 1877 by W.R. Hill, a land developer from Indiana, and Reverend W.H. Smith, a black man. Reverend Smith became the President of the Nicodemus Town Company and Hill, the treasurer. The two founders aggressively promoted the town to the Black refugees of the Deep South. The Reverend Simon P. Roundtree was the first settler, arriving on June 18, 1877. Zack T. Fletcher and his wife, Jenny Smith Fletcher, the daughter of Reverend W.H. Smith, arrived in July and Fletcher was named the Secretary of the Town Company. Smith, Roundtree, and the Fletchers made claims to their property and built temporary homes in dugouts along the prairie.

The Nicodemus Town Company produced numerous circulars to promote the town, inviting “Colored People of the United States” to come and settle in the “Great Solomon Valley.” The Reverend Roundtree became actively involved in the promotion, and worked with a man by the name of Benjamin “Pap” Singleton , a black carpenter from Nashville, who traveled all over the United States distributing the circulars, which portrayed Nicodemus as a place for African-Americans to establish Black self-government. Singleton, who could not read or write, distributed so many circulars that he was sometimes called the “Moses of the Colored Exodus.” The Blacks who decided to emigrate soon acquired the name “Exodusters”.

At the same time, railroads, needing to populate the West to create markets for their services, exaggerated the quality of the soil and climate in this “Western Eden.”

The desperate families of the South listened with rapt attention and in the late summer of 1877, 308 railroad tickets were purchased to take them to the closest railroad point in Ellis, Kansas. The families then walked the remaining fifty-five miles to Nicodemus, arriving in September 1877.

Building homes along the Solomon River in dugouts, the original settlers found more disappointment and privation as they faced adverse weather conditions. In the Promised Land of Kansas, they initially lacked sufficient tools, seed, and money, but managed to survive the first winter by selling buffalo bones and by working for the Kansas Pacific Railroad at Ellis, the city fifty-five miles away where they originally arrived. Others survived with assistance from the Osage First Nation, who provided food, firewood and staples.

Though most stayed, many settlers were disillusioned by the lack of vegetation and the harsh land and made a hasty return to the green fields of Kentucky and Tennessee. Of those who stayed, the spring of 1878 brought hope and opportunity as new Exodusters, bearing horses, oxen and farming tools began to farm the soil.

A local government was established, headed by “President Smith.”

One woman arriving in the spring, Williana Hickman, said years later of arriving at Nicodemus: “When we got in sight of Nicodemus the men shouted, ‘There is Nicodemus!’ Being very sick, I hailed this news with gladness. I looked with all the eyes I had. I said, ‘Where is Nicodemus? I don’t see it.’ My husband pointed out various smokes coming out of the ground and said, ‘That is Nicodemus.’ The families lived in dugouts… the scenery was not at all inviting, and I began to cry.”

Despite the poor living conditions, Williana and her husband, Reverend Daniel Hickman, stayed, organizing the First Baptist Church in a dugout with a sod structure above it. By 1880, a small, one-room, stone sanctuary had been erected at the same site. This structure evolved from limestone to stucco, and in 1975, a new brick sanctuary was built. Today, the church still stands in Nicodemus.

Zachary Fletcher, one of the town’s first settlers, became the first postmaster and the first entrepreneur in Nicodemus, establishing the St. Francis Hotel and a livery stable in 1880. His wife, Jenny Smith Fletcher, became the first postmistress and schoolteacher and one of the original charter members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The complex that Fletcher built, which housed the post office, school, hotel and stable, later became known as the Fletcher-Switzer House and was an important focus of activity in the community. The building still stands in Nicodemus today.

By 1880, Nicodemus had a population of almost 500, boasting a bank, two hotels, three churches, a newspaper, a drug store, and three general stores – surrounded by twelve square miles of cultivated land.

Edward P. McCabe, who joined the colony in 1878, served two terms as state auditor, 1883-1887, the first African American to hold a major state office.

By 1887 Nicodemus had gained more churches, stores, a literary society, an ice cream parlor, a lawyer, another newspaper, a baseball team, a benefit society and a band. Hopes were high in the community when the railroad talked of an extension from Stockton to Nicodemus and in March of 1887, the voters of the Township approved the issuance of $16,000 in bonds to attract the Union Pacific Railroad to the community. Despite the bond issue, the town and the railroad could not agree on financial compensation and the railroad withdrew its offer.

In 1888, the railroad established the extension six miles away south of the Solomon River, leaving Nicodemus a stranded “island”. Businesses fled to the other side of the river to the Union Pacific Railroad camp that later became known as the town of Bogue. With the businesses leaving, Nicodemus began a gradual decline.

Zachary Fletcher, the town’s first entrepreneur, sold his town lots to the original promoter, W. R. Hill, but continued to run his businesses. Eventually, the hotel reverted to Graham County for a time but was brought back into the family in the 1920′s by Fred Switzer, a great-nephew raised by the Fletchers. When Switzer married Ora Wellington in 1921, they made the hotel their home.

Despite all the hardships and calamities that Nicodemus faced, it survived…and thrived.

More than a half-dozen black settlements sprung up in Kansas after the Civil War but Nicodemus is the only one that still stands.

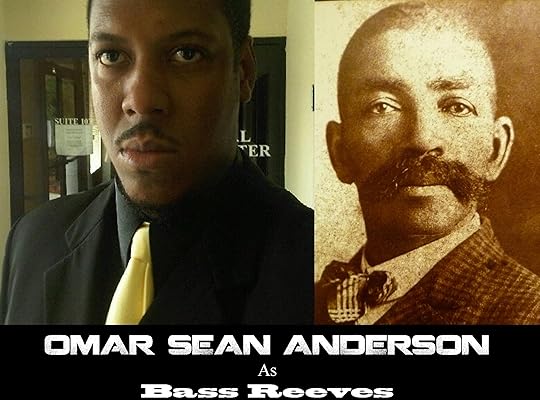

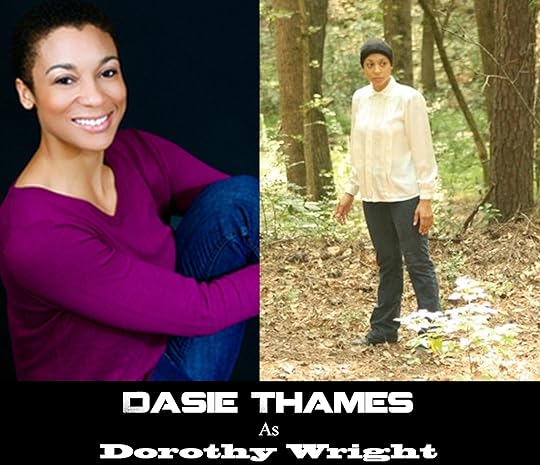

In the world that author Milton Davis and I have developed – the world you will experience in the upcoming Steamfunk feature film, Rite of Passage – the secret to Nicodemus’ survival lies in its four very powerful protectors – Harriet Tubman, Dorothy Wright, John Henry and Bass Reeves and the town’s President, “High” John Konker. Just as the Exodusters have been drawn by promises of self-government, freedom and economic success, the town’s protectors have been drawn by a mysterious and fearsome entity known only as Jedediah Green, who you will learn more of in the next phase of Rite of Passage stories.

The Rite of Passage movie is a pulse-pounding thrill-ride that introduces you to this dark and gritty world of steam, brass and iron and to the origins of its heroes.

With the might of our heroes – and with the imaginations of Milton Davis and Yours Truly – Nicodemus Town Company will never fall.

April 9, 2013

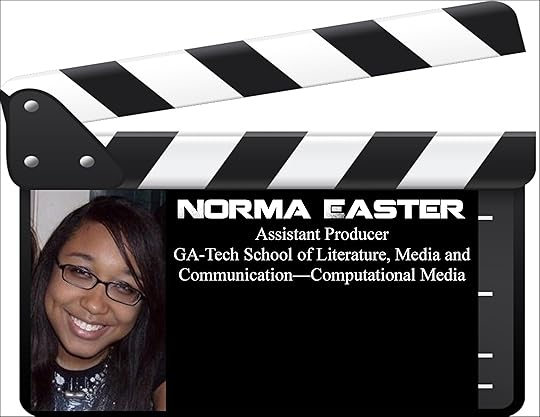

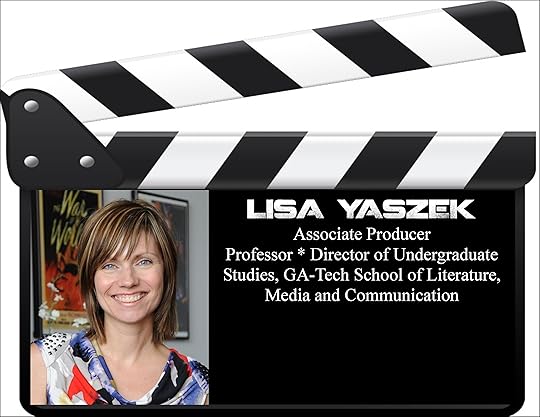

GA-TECH GETS FUNKY! Filmmakers Partner With The Yellow Jackets to Produce the First Steamfunk Feature Film!

Filmmakers Partner With The Yellow Jackets to Produce the First Steamfunk Feature Film!

I was recently contacted by an agent who asked if Rite of Passage – the Steamfunk movie that goes into pre-production in May and production in August – was a student film. I informed her that the film is a collaboration between the professional multimedia companies MVmedia and Roaring Lions Productions and GA-Tech’s School of Literature, Media and Communication, so yes, students will be heavily involved in the making of the film, but under the guidance and leadership of experienced and accomplished film professionals who are the directors, producers and cinematographers on this project.

I informed her that the students will not be treated as “amateurs”, nor is the film going to be amateur or second rate. The students involved in the making of Rite of Passage are expected to be just as professional…just as committed as those who have worked on ten or more projects.

The agent’s response?

“Well, I will probably send a few of my actors to audition, but most of my actors would never act in a student film. I was a bit surprised to hear that most of the actors she represents dismiss programs that have produced some of industry’s best filmmakers and actors. “She needs to educate her people,” I thought.

However, “To be fair,” – as Rite of Passage’s Producer, Akin Danny Donaldson, is fond of saying – he’s from England; everyone from England are fond of saying that – I could come up with a few reasons myself as to why an actor would not want to act in a student film – there is no pay; the filmmakers do not have a lot of experience and are still learning how to talk to and treat actors; and few student films become a success by Hollywood standards. However, from her reaction, I was sure she – or some of her actors – had experienced some Stygian nightmare in doing a student film.

She, or any of her actors, had not; she just thought there was nothing for her people to gain from such projects. She was oblivious to the tremendous opportunity provided by student films to form strong, lasting and mutually beneficial relationships with young, talented, up-and-coming directors, producers, actors and casting directors.

She, or any of her actors, had not; she just thought there was nothing for her people to gain from such projects. She was oblivious to the tremendous opportunity provided by student films to form strong, lasting and mutually beneficial relationships with young, talented, up-and-coming directors, producers, actors and casting directors.

You could very well be working with the next Martin Scorsese or Spike Lee. They are not master directors yet, but “to be fair”, the next Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, Malcolm X, or The Inside Man could be their next film.

Student films often achieve admittance into top notch festivals each year, earning these young filmmakers studio deals and the actors in their films worldwide recognition.

If you choose to act in a student film, there are certain things that you should not negotiate. You should receive a copy of your work in a timely fashion, be fed every six hours, and should not be asked to work longer than a 12-hour day without proper turnaround.

Know that student filmmakers, especially those in the early stages of filmmaking, tend to prioritize their aesthetic vision over an actor’s performance. Don’t be shocked, frustrated, or allow your ego to be bruised if hours are spent on a cool-looking, spinning, overhead dolly shot rather than your sublime performance in a close-up.

Keep in mind that these young filmmakers are attempting to bring their visions to life without large crews and budgets, so – “To be fair” – cut them some slack if things take longer than they should.

Actors, don’t feel ashamed, embarrassed or as if you are “settling” because you are auditioning for a student film. It doesn’t mean that you are a bad actor. Agents submit actors to films by USC, Columbia University and Columbia College Chicago every day.

“To be fair”, however, I will admit that many student films simply stink. The most common reason for such odoriferous works is lack of story. A suicide prone emo teen is a subject, not a story. If your story is about an emo college freshman with a football player roommate whose girlfriend is always trying to convince the emo kid to go out and party – who cares?

The second most common reason for the malodorousness is the student’s reach exceeding his or her grasp. The student tries to tell a story that is too convoluted; uses techniques that are far beyond his or her experience. The more complex the story, the more skill it takes to tell it and the greater likelihood that a relative beginner will fail in the telling of it.

Fortunately, Rite of Passage has some of the best professionals in independent film working on the project and the students chosen to work with us will be the best that GA-Tech has to offer, which, “To be fair,” is saying a lot, as GA-Tech is fast becoming recognized as one of the top film schools in America, particularly in the areas of special effects, sound effects, prop and graphics design and cinematography.

Below are the current professional members of the crew of Rite of Passage. We are all excited to work with the next generation of Scorseses, Lees, Singletons, Spielbergs, Poitiers, Tarantinos, Lucases and”To be fair,” Balogun Ojetades (go ahead, you can laugh)

April 8, 2013

HARRIET TUBMAN HAS GREAT STEAM-FU: Putting the Funk in your Fight Scenes!

HARRIET TUBMAN HAS GREAT STEAM-FU: Putting the Funk in your Fight Scenes!

I have choreographed and / or performed fight scenes for seven films – two “traditional” Hong Kong-style martial arts movies; one gritty urban fantasy; one thriller; one post-apocalyptic science fiction film; one alternate history movie and one comedy.

I have choreographed and / or performed fight scenes for seven films – two “traditional” Hong Kong-style martial arts movies; one gritty urban fantasy; one thriller; one post-apocalyptic science fiction film; one alternate history movie and one comedy.

Filming a fight scene is totally different from shooting a scene of dialogue. It requires much more planning and the director must be able to tell a story through the fight itself.

I would like to share with you what I have learned about shooting and choreographing a fight scene because it is an interesting topic; because I hate it when I watch an otherwise great film fall apart because of its poorly shot fights; and because we go into pre-production for the Steamfunk movie, Rite of Passage, in a month and I want to make you, dear reader, aware of what we are doing and how it is done, because, ultimately, this is your film. We are making this for you.

Begin with the previous action

If your heroine, Harriet Tubman’s last action in the previous sequence you shot was a hook punch, even if you know you are not going to show that punch in a close-up, film it at the start of the next sequence anyway and then keep rolling and shoot that next sequence; this will make your fight appear much smoother and editing the scene will be easier.

Always return your strikes to their point of origin

If you watch martial arts movies with great fight scenes, such as Flashpoint, starring Donnie Yen, or the Bourne movies, then you’ll notice that every time they punch someone, their fist recoils back. By adding this subtle movement to your actors’ hits, it makes the impact of those strikes appear much more powerful and makes the character look as if he or she is really strong.

If you watch martial arts movies with great fight scenes, such as Flashpoint, starring Donnie Yen, or the Bourne movies, then you’ll notice that every time they punch someone, their fist recoils back. By adding this subtle movement to your actors’ hits, it makes the impact of those strikes appear much more powerful and makes the character look as if he or she is really strong.

Always keep your eyes on your opponent

This is an important tip for your actors as well. After an actor is hit, he “sells” the strike as a powerful one by making sure his eyes always return back to his opponent. So, if Harriet Tubman punches P.T. Barnum in the jaw with that hook punch, the actor playing Barnum would sell the punch by snapping his head sideways, looking over his shoulder and then snap his gaze right back to the actor playing General Tubman.

This also allows your actors to communicate their readiness before the next blow is thrown, thus helping you to avoid accidents in case one of your actors is not ready or has forgotten the next move. Remember, when filming fight scenes, safety first!

Shoot the entire fight wide and then move in for close-ups, over shoulder and medium shots

Not following this suggestion can cause you to run into some editing problems as a result. Often, when we shoot the intense over shoulder, medium and close-up shots first, which require much more facial expression along with technique to sell the fight, we forget to shoot the wide shot. If you don’t have a wide angle of your fight, you run the risk of the fight appearing choppy or worse, appearing disorienting to the audience.

Move your camera with the movements

Although this is often overdone in Western films to mask the lack of striking power possessed by most actors, this technique can add a little something extra to your fight scenes.

Although this is often overdone in Western films to mask the lack of striking power possessed by most actors, this technique can add a little something extra to your fight scenes.

Moving with the punches makes the strike appear faster and by stopping the camera’s movement right as the punch connects, adds a jerky feel that can often make a punch appear more violent on screen. Shoot moving shots after your essential stationary shots.

Editing and Sound Design turn good fights into great fights

A great editor lets us forget that we are simply watching a fight scene and pulls us into the scene by making the action seamless.

This is the most essential part of the fight to be done.

Coming in a close second is the post production music and Foley (sound effects).

Don’t believe me? Watch any fight scene with the audio muted – that scene feels far less compelling. The hits become weaker and the fight now feels flat and totally fake.

The audio is edited and mixed with utmost acoustic continuity for fight scenes, because, while our eyes are okay with being cheated by the illusion created by camera angles, slow motion and the like, our ears are not. Since our ears are much more vital to our sense of balance, we notice the slightest break or hiccup in the audio with a 15 – 20 times higher temporal precision than we notice in the video.

So actually, fight scenes are not made sound real at all. But you are willing to let yourself drawn into them because of a flawless sound design.

Boot Camp or Bust

On every film in which I am the Fight Choreographer, I conduct a Fighters’ Boot Camp. This camp – which can run over several days or over many hours in one day, depending on time and budget – is required for any actor who has a fight scene in the film to attend and strongly suggested for the Director and Cinematographer to attend as well.

On every film in which I am the Fight Choreographer, I conduct a Fighters’ Boot Camp. This camp – which can run over several days or over many hours in one day, depending on time and budget – is required for any actor who has a fight scene in the film to attend and strongly suggested for the Director and Cinematographer to attend as well.

This Boot Camp teaches non-martial artists how to move, hit and react to hits so they appear to be martial arts experts on screen. For the martial artists in the film, we teach them how to make their techniques look good on screen – most “real” martial arts techniques do not look powerful or cool onscreen – and how to sell the hits and the reaction to hits.

On one set, I worked with a former professional boxing champion. He did not want to do “that fake stuff” and wanted the actor to really strike him on film. I expressed concern for his safety. He said the actor – a woman – couldn’t hurt him. We humored him and shot it the way he wanted, as the scene was supposed to be comedic anyway and I wanted to teach him a lesson. During one sequence, the actor he was fighting struck him in the jaw with one of her “non-fake” punches and rocked him badly, dropping him to his knees.

Lesson learned. We kept that scene in the film.

When a fight scene seems real to you, the actors and the film crew have done a great job and have successfully executed the clearest demonstration of the magic that is filmmaking.

I now leave you with a few fight scenes featuring Yours Truly and my favorite fight scene of all time, featuring actors Donnie Yen and Wu Jing. Enjoy!

April 4, 2013

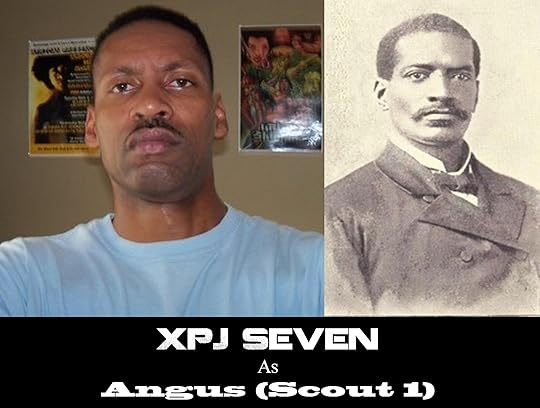

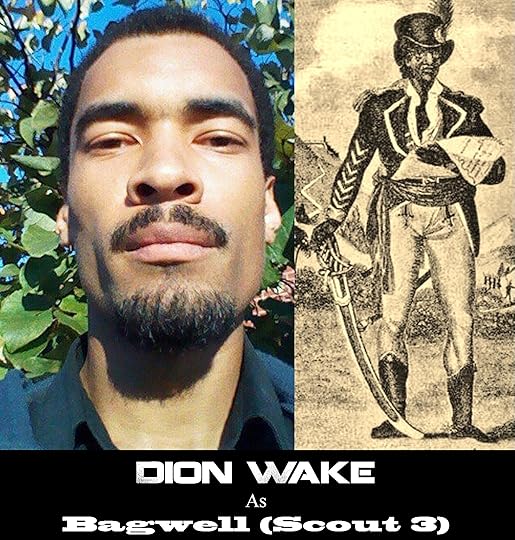

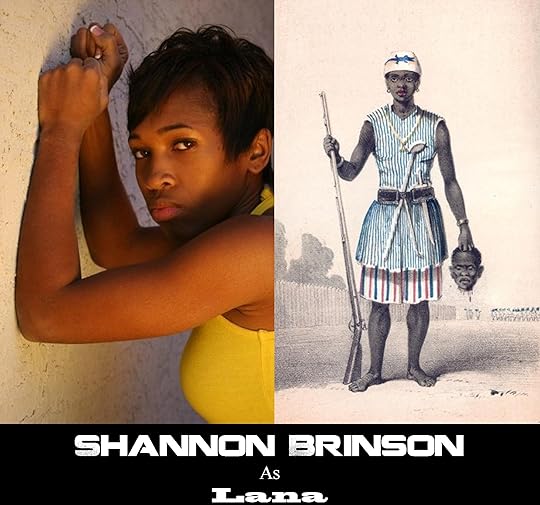

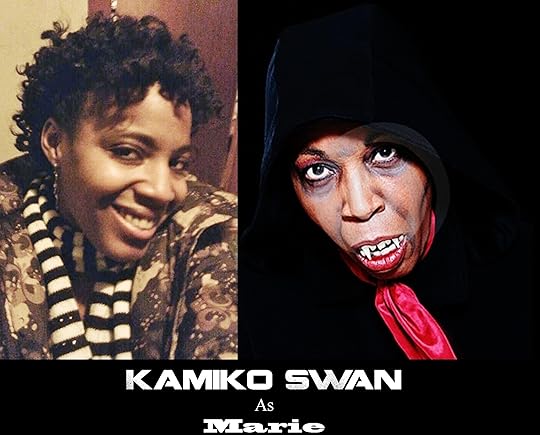

THE MAKING OF A STEAMFUNK MOVIE: Part 2, The Cast

THE MAKING OF A STEAMFUNK MOVIE: Part 2, The Cast

What is the most important element of creating a film?

What is the most important element of creating a film?

Is it a great script? The film’s director? The type of camera and lenses you shoot with?

Or is casting the right actor most important?

Casting a film is much like cooking – you need the right ingredients in just the right amounts to create something that’s palatable and satisfying. Casting professionals are chefs. They take a director’s vision and a writer’s story, and concoct a ten-course meal that’s worthy of a five-star restaurant. If the recipe is off, however, even a potentially great film could easily turn out to be average.

Actors, especially A-list players, cost a lot of money. Money that – contrary to what you might believe – is well-deserved. I have acted in several movies and I can tell you, it is some of the most demanding work I have ever done. Imagine putting on sixty pounds of muscle to play a professional boxer, or learning to ride a horse and fire a longbow from horseback – all while looking good and making it look like you have been riding horses and firing arrows from their backs since you were knee-high to a grasshopper.

Lesser-known actors don’t have the same salary requirements, but they may lack exposure or experience.

Thus, the Casting Director walks a fine line between beauty, budget, and risk – carefully assessing each role and the type of actor you need to make that character successful.

Picture Katt Williams playing Django in Django Unchained, or Honey Boo Boo playing Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. Chances are, they would have flopped.

Picture Katt Williams playing Django in Django Unchained, or Honey Boo Boo playing Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. Chances are, they would have flopped.

The Casting Director, or CD, is the individual responsible for finding and auditioning actors for the roles in a movie. CDs work closely with the director and producer to find the talent they are searching for – the talent right for a specific role.

Casting directors are pros at matching the right actor to the right role. They are the matchmakers of the filmmaking industry, arranging auditions, casting calls, and callbacks and their help is indispensable.

In making their decisions, Casting Directors examine a number of factors, including an actor’s experience, “chops” (proficiency in acting), physical characteristics, and other special talents, such as martial arts training or stunt experience.

If you take on the responsibilities of Casting Director for a film, here are a few tips I would like to share. I learned these the hard way – through assisting directors in casting films, through auditioning for films and through making mistakes during production of my own films.

If you take on the responsibilities of Casting Director for a film, here are a few tips I would like to share. I learned these the hard way – through assisting directors in casting films, through auditioning for films and through making mistakes during production of my own films.

1. Avoid using one of your crew members as an actor in the film. You diminish the size –and therefore the efficiency – of your production team when you pull one of them out to act. A crew of four people that loses one to become a performer is diminished 25%. Usually this drastic trade-off becomes visible on screen in numerous ways.

“Spike Lee and Quinton Tarantino do it all the time,” you say? Yep. They are exceptions. Not the rule.

2. Try to work with those who have a reason to commit to the film. Actors and even acting students have a reason to participate in a film until the very end because it is important for them to have an acting reel, meaning samples of them performing. The better the project is, the better their reel, so they have a strong incentive to perform well. Not only do they get a credit on a film, but the reel can lead to other acting gigs.

However, a close friend who is a professor of English Literature might be excited about – and even agree to dust off those college acting skills and be in – your movie, but after the first ten-hour production day, they may start to lose interest. With mid-terms coming up, with an impatient wife to appease and teaching assistants to maintain, suddenly the thought of sticking around for three more shooting days isn’t so appealing to the good old professor. Frequently, good friends find the limits of their friendship on film productions.

3. Think twice about casting family members. Family relations are often complex; add to that the stress and arduousness of the filmmaking process, and you’re working with a volatile mixture – kind of like a gallon of nitroglycerin in the hands of your ninety-seven year old uncle after he has had a decanter of coffee, two Krispy Kreme donuts and thirteen cigarettes. Imagine asking your mother to redo her lines after she has flubbed them for the tenth time, but is convinced the last take was “a keeper”. “But you directed your wife in that action film, A Single Link and in Rite of Passage: Initiation,” you say? Again…exceptions to the rule.

4. Always remember that it takes a skilled director, and lots of patience, to get a great performance out of a non-actor. For most films, casting skilled actors is important in order to get what you need for your film. Even if your film has no dialogue, a good actor can bring a new interpretive energy, authenticity, and creative resources to the project.

4. Always remember that it takes a skilled director, and lots of patience, to get a great performance out of a non-actor. For most films, casting skilled actors is important in order to get what you need for your film. Even if your film has no dialogue, a good actor can bring a new interpretive energy, authenticity, and creative resources to the project.

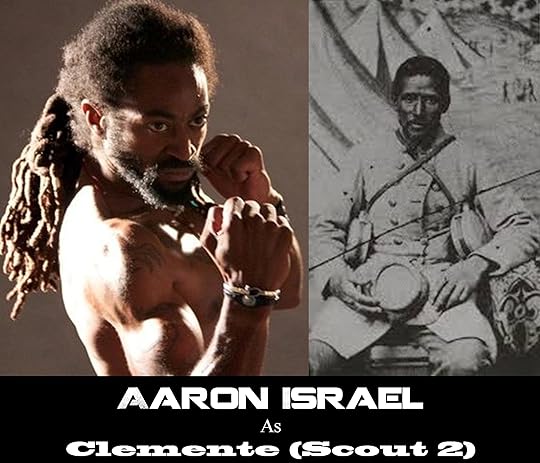

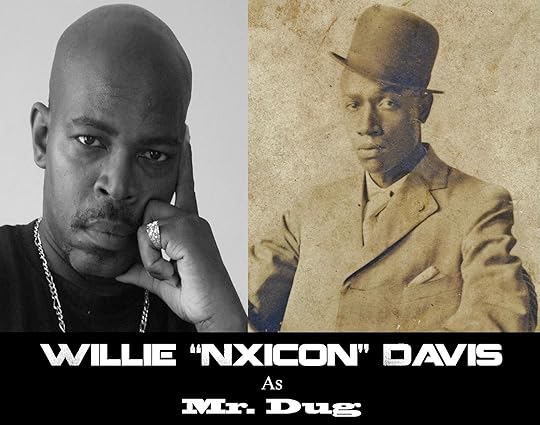

Finally, I would like to share the current cast of Rite of Passage, the first Steamfunk film, with you. As we add more actors to the cast, I will edit this section, so please, check back often.

Oh, and if you happen to be an actor, a Steampunk maker or Steampunk fashion designer / costume maker and are interested in working on this awesome film, please join us Thursday, April 18, 2013 at GA-Tech in room 343 of the Skiles Building at 11:00 am for an Information Session.

March 31, 2013

THE MAKING OF A STEAMFUNK MOVIE: Pt. 1, the Crew

THE MAKING OF A STEAMFUNK MOVIE: Pt. 1, the Crew

When I left Howard University – and my despised major in Finance – in 1986 (don’t do the math) to pursue my vision of novelist, screenwriter and film director, my family – particularly my mother was supportive. My sister, Alesia, however – a film and video producer for the Air Force – did not warn me about what I was getting myself into.

When I left Howard University – and my despised major in Finance – in 1986 (don’t do the math) to pursue my vision of novelist, screenwriter and film director, my family – particularly my mother was supportive. My sister, Alesia, however – a film and video producer for the Air Force – did not warn me about what I was getting myself into.

I enrolled in Columbia College – the renowned college of the Fine Arts in Chicago – and my training in film, which I just knew would be easy and fun every minute, began.

And so did work ten times more demanding than any Finance, Economics, or Statistics class ever was.

Easy? My ass!

Fun? Hell no!

The work was grueling; tiresome; boring; lonely.

Wait a minute…lonely?

The first week of my Film Directing I Class was a solo directing project. Unbeknownst to us ignorant students, that project was designed for the sole purpose of teaching us – the hard way – that film is always a collaborative effort. Anyone who tries to be a one-man film crew is about as sharp as a bowl of Jell-O.

The first week of my Film Directing I Class was a solo directing project. Unbeknownst to us ignorant students, that project was designed for the sole purpose of teaching us – the hard way – that film is always a collaborative effort. Anyone who tries to be a one-man film crew is about as sharp as a bowl of Jell-O.

For those of you looking to make a movie, but you do not have access to a multimillion-dollar budget, you may have to assume more than one responsibility to make your film. While it is possible – and often necessary – to wear two or three hats when making a film, it is not recommended. Search hard for qualified and experienced people to work with. The more you do, the more the quality of your film suffers and the quicker you will burn yourself out.

In May, we begin pre-production on the Steamfunk feature film, Rite of Passage. We start shooting in August. This is the bare minimum crew we will begin with:

Producer: A film producer creates the conditions for making movies. The producer initiates, coordinates, supervises, and controls matters such as raising funding, hiring key personnel, and arranging for distributors. The producer is involved throughout all phases of the filmmaking, from development to “delivery” of a project.

Producer: A film producer creates the conditions for making movies. The producer initiates, coordinates, supervises, and controls matters such as raising funding, hiring key personnel, and arranging for distributors. The producer is involved throughout all phases of the filmmaking, from development to “delivery” of a project.

Executive producer: In major productions, can sometimes be a representative or CEO of the film studio. Or the title may be given as an honorarium to a major investor. Often they oversee the financial, administrative and creative aspects of production, though not always in a technical capacity. In smaller companies or independent projects, it may be synonymous with creator/writer. Often, a “Line Producer” is awarded this title if this producer has a lineage of experience, or is involved in a greater capacity than a “typical” line producer. E.G – working from development through post, or simply bringing to the table a certain level of expertise.

Associate producer: Usually acts as a representative of the Producer, who may share financial, creative, or administrative responsibilities, delegated from that producer. Often, a title for an experienced film professional acting as a consultant or a title granted as a courtesy to one who makes a major financial, creative or physical contribution to the production.

Script Supervisor: The script supervisor maintains a daily log of the shots covered and their relation to the script during the course of a production, acts as chief continuity person, and acts as an on-set liaison to the post-production staff. They maintain logs of all shots and act as the chief continuity person on set, performing daily cross-referencing with the continuity stills photographer to ensure shots remain accurate and in logical order.

Continuity Stills Photographer: The continuity stills photographer uses a digital still camera to establish continuity referents for each shot covered in a day of shooting. These shots are cross-referenced with the script supervisor’s log for accessibility on set. The continuity stills photographer takes pictures of each shot covered, paying particular attention to the in-point and out-point of a shot – a photograph is taken just before the director says “action,” and immediately after he or she says “cut.”

Director: The director is responsible for overseeing the creative aspects of a film, including controlling the content and flow of the film’s plot, directing the performances of actors, organizing and selecting the locations in which the film will be shot, and managing technical details such as the positioning of cameras, the use of lighting, and the timing and content of the film’s soundtrack. Though the director wields a great deal of power, they are ultimately subordinate to the film’s producer or producers. Some directors, especially more established ones, take on many of the roles of a producer, and the distinction between the two roles is sometimes blurred.

Director: The director is responsible for overseeing the creative aspects of a film, including controlling the content and flow of the film’s plot, directing the performances of actors, organizing and selecting the locations in which the film will be shot, and managing technical details such as the positioning of cameras, the use of lighting, and the timing and content of the film’s soundtrack. Though the director wields a great deal of power, they are ultimately subordinate to the film’s producer or producers. Some directors, especially more established ones, take on many of the roles of a producer, and the distinction between the two roles is sometimes blurred.

Stunt Coordinator: Where the film requires a stunt, and involves the use of stunt performers, the stunt coordinator will arrange the casting and performance of the stunt, working closely with the director. This includes Fight Choreographers – stunt coordinators who specialize in the casting, design and performance of fight scenes.

Production Designer: A production designer is responsible for creating the physical, visual appearance of the film – settings, costumes, properties, character makeup, all taken as a unit. The production designer works closely with the director and the cinematographer to achieve the ‘look’ of the film.

Director of Photography / Cinematographer: The director of photography is the chief of the camera and lighting crew of the film. The DP makes decisions on lighting and framing of scenes in conjunction with the film’s director. Typically, the director tells the DP how they want a shot to look, and the DP chooses the correct aperture, filter, and lighting to achieve the desired effect.

Director of Photography / Cinematographer: The director of photography is the chief of the camera and lighting crew of the film. The DP makes decisions on lighting and framing of scenes in conjunction with the film’s director. Typically, the director tells the DP how they want a shot to look, and the DP chooses the correct aperture, filter, and lighting to achieve the desired effect.

Camera Operator: The camera operator uses the camera at the direction of the cinematographer / director of photography, or the film director to capture the scenes on film. Generally, a cinematographer or director of photography does not operate the camera, but sometimes these jobs may be combined.

Boom Operator: The boom operator is an assistant to the production sound mixer, responsible for microphone placement and movement during filming. The boom operator uses a boom pole, a long pole made of light aluminum or carbon fiber that allows precise positioning of the microphone above or below the actors, just out of the camera’s frame. The boom operator may also place radio microphones and hidden set microphones.

Boom Operator: The boom operator is an assistant to the production sound mixer, responsible for microphone placement and movement during filming. The boom operator uses a boom pole, a long pole made of light aluminum or carbon fiber that allows precise positioning of the microphone above or below the actors, just out of the camera’s frame. The boom operator may also place radio microphones and hidden set microphones.

Location Scout: Does much of the actual research, footwork and photography to document location possibilities.

Location Scout: Does much of the actual research, footwork and photography to document location possibilities.

Film Editor: The film editor is the person who assembles the various shots into a coherent film, with the help of the director.

Sound Designer: The sound designer, or “supervising sound editor”, is in charge of the post-production sound of a movie. Sometimes this may involve great creative license, and other times it may simply mean working with the director and editor to balance the sound to their liking.

Composer: The composer is responsible for writing the musical score for a film.

Foley Artist: The foley artist is the person who creates the sound effects for a film.

Key Makeup Person: The key makeup person applies and maintains the cast’s makeup, working in coordination with the script supervisor and the continuity stills photographer.

Key Hairdresser: The key hairdresser dresses and maintains the cast’s hair, working in coordination with the script supervisor and the continuity stills photographer.

Costume Designer: The costume designer works under the supervision of the director and the art director to design, obtain, assemble, and maintain the costumes for a production. Costume designers develop costuming concepts and the design of costumes in coordination with the art director, production designer, and DP.

Costume Designer: The costume designer works under the supervision of the director and the art director to design, obtain, assemble, and maintain the costumes for a production. Costume designers develop costuming concepts and the design of costumes in coordination with the art director, production designer, and DP.

This is the crew I am working with, plus the assistants for each member of the crew, caterers and security. I bet no Financier ever had to work with so many people – from a couple of months to a year or more – just to complete one project.

Such is the life of a filmmaker, but I love it and when you see the fruit of the labor of our crew, when Rite of Passage hits the silver screen at the Black Science Fiction Film Festival in February, 2014, you’ll love it – and us – too!

More funk to come. Stay tuned, Steamfunkateers!

If you would like to be a part of the making of this film and live in or near Atlanta, please join us at the Information Session at Georgia Tech Thursday, April 18, 2013; Skiles Building; Room 343 at 11:00 am. We will discuss cast and crew needs, scheduling and benefits to be enjoyed by all involved!

March 27, 2013

STEAMFUNK FICTION: A Darker Shade of Brown

STEAMFUNK FICTION: A Darker Shade of Brown

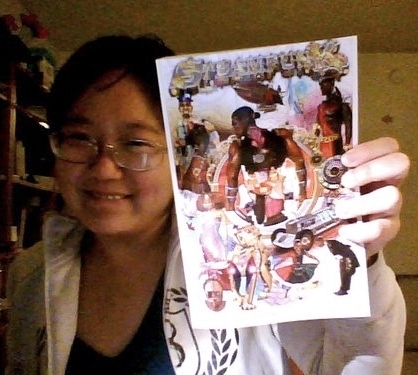

On February 22, 2013, the long-awaited, highly anticipated, hotly debated and deeply contemplated Steamfunk anthology debuted at AnachroCon and worldwide.

On February 22, 2013, the long-awaited, highly anticipated, hotly debated and deeply contemplated Steamfunk anthology debuted at AnachroCon and worldwide.

The book has done exceptionally well since its release, reviews are favorable and the popularity of Steamfunk – the anthology and the movement – is growing exponentially.

Readers are asking for more Steamfunk, which is really quite shocking; not because Steamfunk fiction isn’t absolutely funktastic – it is – but because, after reading nearly five-hundred pages chock full o’ funky goodness, I would figure they would need to take a breather and inhale a bit of funk-free air.

Readers are asking for more Steamfunk, which is really quite shocking; not because Steamfunk fiction isn’t absolutely funktastic – it is – but because, after reading nearly five-hundred pages chock full o’ funky goodness, I would figure they would need to take a breather and inhale a bit of funk-free air.

Much to my surprise and glee, I was mistaken. “More Steamfunk!” is the cry. Even the august group of authors who contributed their fascinating fables of funkasticity to the anthology has demanded a second volume – Steamfunk II: Dieselfunk.

To tide you over until the final verdict on the production of a second volume is delivered, I offer you a listing of several books that are either Steamfunk, or Steampunk, with a main character of African descent.

Here goes. Enjoy!

And remember: keep it funky!

Moses: The Chronicles of Harriet Tubman (Books 1 & 2) by Balogun Ojetade

“I’m gon’ drive the evil out and send it back to Hell, where it belong!” – Harriet Tubman Harriet Tubman: Freedom fighter. Psychic. Soldier. Spy. Something…more. Much more. In “MOSES: The Chronicles of Harriet Tubman (Book 1: Kings * Book 2: Judges)”, the author masterfully transports you to a world of wonder…of horror…of amazing inventions, captivating locales and extraordinary people. In this novel of dark fantasy (with a touch of Steampunk), Harriet Tubman must match wits and power with the sardonic John Wilkes Booth and a team of hunters with powers beyond this world in order to save herself, her teenaged nephew, Ben and a little girl in her care – Margaret. But is anyone who, or what, they seem?

The Switch and The Switch II: Clockwork by Valjeanne Jeffers

Includes The Switch I and The Switch II! York is a city of contradictions. Women are hard-pressed for lovers, because lovemaking can be dangerous. The upper city is powered by computers, the underground by steam. And the wealthy don’t work for a living, underdwellers do it for them. But certain underdwellers have a big problem with this arrangement. And so does the time keeper. Welcome to the Revolution…

The Sivad Chronicles: The Possession and A Debt to Pay by Milton J. Davis

Samoht Sivad, sorcerer and warrior, goes missing after a garrison tour. Naheem, his cousin and acting patriarch of the Sivad clan, sets out to find him. His journey puts him on the path of a man who has found a way to seek revenge from beyond his grave.

The Possession introduces the alternate world of the Sivads, a North America whose present is entirely unique from the world in which we live, a land of beauty, diversity…and magic.

In the second Sivad Chronicle adventure, brothers Samoht and Vel find themselves exiled from the Nations by their cousin Naheem for different reasons. They embark on a journey to the Motherland to seek the secrets of their clan and their mysterious power. Naheem sets out to right his cousins’ wrongs while they are away and finds himself in his own adventure, one that will be as dangerous as it is enlightening.

Immortal 4: Collision of Worlds by Valjeanne Jeffers

Rules were broken. Now the price must be paid. “The New World awoke to a roaring wind, light blazed from the mirror—swallowing the planet—a churning, savage vortex. Tundra’s inhabitants cried out, as their flesh bled from their bones like wet clay. The world shuddered. And was still.” The Immortals broke the rules. As punishment, Karla and Joseph are transported to a steam powered realm. Tehotep is now ruler of the empire. Karla is his concubine. Vampires roam the streets. Androids enforce a demon’s will. And there is no way out. Except death…

Steamfunk Issue 0 Written by Eric Doty; Illustrated by Luke McKay

A comic book for all ages, that includes a bit of Steampunk and a pinch of Dieselpunk with Western and Fantasy elements. Its biggest influences are the film, The Wizard of Oz and the television series, Firefly. The “funk” in the title serves a dual purpose, referring to the musical references throughout the story as well as the state of the world the characters exist in. The story follows the adventures of a gutsy delivery girl, Deaux, as she unravels truths that she may not be prepared for.

John Henry: The Steam Age Written and Illustrated by Dwayne Harris

John Henry, a former slave, wasn’t about to let some new-fangled steam hammer replace his ability to earn an honest wage as a steel-driving man. He’d beat that machine, or die with his hammer in his hand. We all know the outcome of that legendary contest. In this alternate history, however, John doesn’t die in his heroic effort, but instead slips into a coma, only to awaken to his worst nightmare. A robotic uprising has occurred, and a new age has dawned – the Steam Age! Now the only thing that can free the human race from the very machines they’ve created is John and his hammer. John Henry: The Steam Age is an exciting re-imagining of the story of John Henry in a steampunk setting.

Clementine by Cherie Priest

Maria Isabella Boyd’s success as a Confederate spy has made her too famous for further espionage work, and now her employment options are slim. Exiled, widowed, and on the brink of poverty…she reluctantly goes to work for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in Chicago.

Adding insult to injury, her first big assignment is commissioned by the Union Army. In short, a federally sponsored transport dirigible is being violently pursued across the Rockies and Uncle Sam isn’t pleased. The Clementine is carrying a top secret load of military essentials – essentials which must be delivered to Louisville, Kentucky, without delay.

Intelligence suggests that the unrelenting pursuer is a runaway slave who’s been wanted by authorities on both sides of the Mason-Dixon for fifteen years. In that time, Captain Croggon Beauregard Hainey has felonied his way back and forth across the continent, leaving a trail of broken banks, stolen war machines, and illegally distributed weaponry from sea to shining sea.

And now it’s Maria’s job to go get him.

He’s dangerous quarry and she’s a dangerous woman, but when forces conspire against them both, they take a chance and form an alliance. She joins his crew, and he uses her connections. She follows his orders. He takes her advice.

And somebody, somewhere, is going to rue the day he crossed either one of them.

There you have it, y’all! Enough funk to last you for quite some time. If you crave even more funky goodness, please, check out my fiction stories on this site.

Stay tuned! There is plenty more Steamfunk to come!

March 25, 2013

The Looming Shadow of Death: The Black Vote in the Age of Steam!

The Looming Shadow of Death: The Black Vote in the Age of Steam!

At the time of Ulysses S. Grant’s election to the presidency in 1868, Americans were struggling to reconstruct a nation torn apart by war. Voting rights for freed blacks proved a big problem. Reconstruction Acts passed after the war called for black suffrage in the Southern states, but many – in the South and the North – felt the approach unfair. The Acts did not apply to the North.

At the time of Ulysses S. Grant’s election to the presidency in 1868, Americans were struggling to reconstruct a nation torn apart by war. Voting rights for freed blacks proved a big problem. Reconstruction Acts passed after the war called for black suffrage in the Southern states, but many – in the South and the North – felt the approach unfair. The Acts did not apply to the North.

Contrary to the perception of the North being a utopian promised land for Black people, 11 of the 21 Northern states did not allow blacks to vote in elections. Most of the Border States, where one-sixth of the nation’s black population resided, also refused to allow blacks to vote.

The Republicans’ answer to the problem of the black vote was the addition of an amendment to the Constitution that guaranteed black suffrage in all states, regardless of the party that controlled the government. Congress spent the days between Grant’s election and his inauguration drafting this new amendment, which would be the 15th one added to the Constitution.

The writers of the Fifteenth Amendment produced three different versions of the document. The first of these prohibited states from denying citizens the vote because of their race, color, or the previous experience of being a slave. The second version prevented states from denying the vote to anyone based on literacy, property, or the circumstances of their birth. The third version stated plainly and directly that all male citizens who were 21 or older had the right to vote.

Determined to pass the amendment, Congress ultimately accepted the first and most moderate of the versions as the one presented for a vote. This took some wrangling in the halls of Congress, however, because many Congressmen felt that the first version did not go far enough, and that it left too many loopholes.

Determined to pass the amendment, Congress ultimately accepted the first and most moderate of the versions as the one presented for a vote. This took some wrangling in the halls of Congress, however, because many Congressmen felt that the first version did not go far enough, and that it left too many loopholes.

Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment on February 26, 1869. But some states resisted ratification. At one point, the ratification count stood at 17 Republican states approving the amendment and four Democratic states rejecting it. Congress still needed 11 more states to ratify the amendment before it could become law.

All eyes turned toward those Southern states which had yet to be readmitted to the Union. Acting quickly, Congress ruled that in order to be let into the Union, these states had to accept both the Fifteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to all people born in the United States, including former slaves. Left with no choice, the Southern states ratified the amendments and were restored to statehood.

Finally, on March 30, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution. To many, it felt like the last step of reconstruction. But just as many had predicted, Southerners found ways to prevent blacks from voting. Democrats and Republicans clashed over the right of former slaves to enter civic life an white supremacist vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan gained strength as many whites refused to accept blacks as their equals.

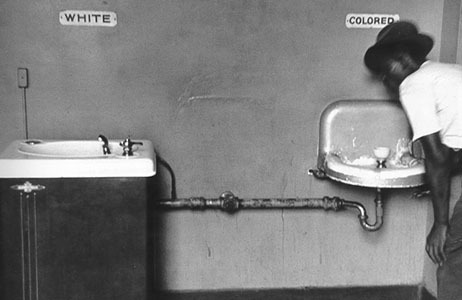

Jim Crow – the racial caste system and series of rigid anti-black laws that operated primarily, but not exclusively, in Southern and Border States, between 1877 and the mid-1960s – was a way of life. Under Jim Crow, African Americans were relegated to the status of second class citizens.

During this era, many Christian ministers and theologians taught that whites were the Chosen people, and that blacks – all victims of the curse of Noah’s son Ham – were cursed to be drawers of water and hewers of wood (i.e. servants).

Craniologists, eugenicists, phrenologists, and Social Darwinists, at every educational level, buttressed the belief that blacks were, by nature, intellectually and culturally inferior to whites. Politicians gave eloquent speeches on the great danger of integration – the mongrelization of the white race. Newspaper and magazine writers routinely referred to blacks as niggers, coons, and darkies; and their articles reinforced anti-black stereotypes. All major societal institutions reflected and supported the oppression of Black people.

Craniologists, eugenicists, phrenologists, and Social Darwinists, at every educational level, buttressed the belief that blacks were, by nature, intellectually and culturally inferior to whites. Politicians gave eloquent speeches on the great danger of integration – the mongrelization of the white race. Newspaper and magazine writers routinely referred to blacks as niggers, coons, and darkies; and their articles reinforced anti-black stereotypes. All major societal institutions reflected and supported the oppression of Black people.

Under Jim Crow, the following “norms” were enforced:

A black boy or man could not shake hands with a white male because it implied being socially equal. And if a black boy or man dared to offer his hand or any other part of his body to a white woman, he risked being accused of – and hanged, castrated or beaten to death for – rape.

Blacks and whites were not supposed to eat together. If they did eat together, whites were to be served first, and some sort of partition was to be placed between them.

Under no circumstance was a black man to offer to light the cigarette of a white woman – a gesture considered an implication of intimacy.

Blacks were not allowed to show public affection toward one another because it offended whites.

Jim Crow etiquette prescribed that blacks were introduced to whites, never whites to blacks. For example: “Mr. Sam (the white person), this is Cleophus (the black person), that I spoke to you about.”

Whites did not use courtesy titles of respect when referring to blacks – Mr., Mrs., Miss., Sir, or Ma’am was never used. Instead, blacks were called by their first names. However, blacks had to use courtesy titles when referring to whites, and were not allowed to call them by their first names.

If a black person rode in a car driven by a white person, the black person sat in the back seat, or the back of a truck.

White motorists had the right-of-way at all intersections.

In conversing with whites, Black people were to follow these simple rules:

Never assert or even intimate that a white person is lying.

Never impute dishonorable intentions to a white person.

Never suggest that a white person is from an inferior class.

Never lay claim to, or overly demonstrate, superior knowledge or intelligence.

Never curse a white person.

Never laugh derisively at a white person.

Never comment upon the appearance of a white female.

In 1890, Louisiana passed the “Separate Car Law,” which purported to aid passenger comfort by creating “equal but separate” cars for blacks and whites. This was a ruse. No public accommodations, including railway travel, provided blacks with equal facilities. The Louisiana law made it illegal for blacks to sit in coach seats reserved for whites, and whites could not sit in seats reserved for blacks. In 1891, a group of blacks decided to test the Jim Crow law. They had Homer A. Plessy, who was seven-eighths white and one-eighth black (therefore, black), sit in the white-only railroad coach. He was arrested. Plessy’s lawyer argued that Louisiana did not have the right to label one citizen as white and another black for the purposes of restricting their rights and privileges. The Supreme Court stated that so long as state governments provided legal process and legal freedoms for blacks, equal to those of whites, they could maintain separate institutions to facilitate these rights. The Court, by a 7-2 vote, upheld the Louisiana law, declaring that racial separation did not necessarily mean an abrogation of equality.

In practice, the tragic process that came to be known as Plessy, represented the legitimization of two societies: one white, and advantaged; the other, black, disadvantaged and despised.

Blacks were denied the right to vote by grandfather clauses – laws that restricted the right to vote to people whose ancestors had voted before the Civil War – by poll taxes – fees charged to poor blacks who desired to vote – white primaries – only Democrats could vote; only whites could be Democrats – and literacy tests in which you could only vote if you could name all the Vice Presidents and Supreme Court Justices throughout America’s history.

Jim Crow states passed statutes severely regulating social interactions between the races. Jim Crow signs were placed above water fountains, door entrances and exits, and in front of public facilities. There were separate hospitals for blacks and whites, separate prisons, separate public and private schools, separate churches, separate cemeteries, separate public restrooms, and separate public accommodations. In most instances, the black facilities were grossly inferior — generally, older, less-well-kept. In other cases, there were no black facilities — no Colored public restroom, no public beach, no place to sit or eat. Plessy gave Jim Crow states a legal way to ignore their constitutional obligations to their black citizens.

Jim Crow states passed statutes severely regulating social interactions between the races. Jim Crow signs were placed above water fountains, door entrances and exits, and in front of public facilities. There were separate hospitals for blacks and whites, separate prisons, separate public and private schools, separate churches, separate cemeteries, separate public restrooms, and separate public accommodations. In most instances, the black facilities were grossly inferior — generally, older, less-well-kept. In other cases, there were no black facilities — no Colored public restroom, no public beach, no place to sit or eat. Plessy gave Jim Crow states a legal way to ignore their constitutional obligations to their black citizens.

Blacks who violated Jim Crow norms – such as drinking from the white water fountain or trying to vote – risked their homes, jobs and even their lives. Whites could physically beat blacks with impunity. Blacks had little legal recourse against these assaults because the Jim Crow criminal justice system – the police, prosecutors, judges, juries, and prison officials – was all white.

Violence was instrumental for Jim Crow. It was a method of social control. The most extreme forms of Jim Crow violence were lynchings.

Violence was instrumental for Jim Crow. It was a method of social control. The most extreme forms of Jim Crow violence were lynchings.

Lynchings were public murders carried out by mobs. Between 1882, when the first reliable data were collected, and 1968, when lynchings had become rare, there were 4,730 known lynchings; 3,440 of those were of black men and women. Most of the victims of these lynchings were hanged or shot, but many were burned at the stake, castrated, beaten with clubs, or dismembered.

In the mid-1800s, whites constituted the majority of victims, as well as perpetrators, of lynching. However, by the period of Reconstruction, blacks became the most frequent lynching victims. This is an early indication that lynching was used as an intimidation tool to keep the newly freed blacks, “in their places.”

The great majority of lynchings occurred in Southern and Border States, where the resentment against blacks ran deepest. The southern states accounted for nine-tenths of lynchings. More than two thirds of the remaining one-tenth occurred in the six states which immediately border the South.

Under Jim Crow any and all sexual interactions between black men and white women was illegal, illicit, socially repugnant, and within the Jim Crow definition of rape. Although only 19.2 percent of the lynching victims between 1882 and 1951 were even accused of rape, lynching was often supported by the popular belief that such sadistic murder was necessary to protect white women from black rapists. In fact, most blacks were lynched for demanding civil rights, violating Jim Crow etiquette or laws, or in the aftermath of race riots.

Lynchings were most common in small and middle-sized towns where blacks often were economic competitors to local whites. These whites resented any economic and political gains made by blacks. Members of lynch mobs were seldom arrested, and if arrested, rarely convicted, as at least one-half of the lynchings were carried out with police officers participating in them, and in nine-tenths of the others, the officers condoned the mob action.

Lynching served many purposes: it was cheap entertainment; it served as a rallying, uniting point for whites; it functioned as an ego-boost for low-income, low-status whites; it was a method of defending white domination and it helped stop or retard the fledgling social equality movement.

Lynching served many purposes: it was cheap entertainment; it served as a rallying, uniting point for whites; it functioned as an ego-boost for low-income, low-status whites; it was a method of defending white domination and it helped stop or retard the fledgling social equality movement.

Many blacks resisted the indignities of Jim Crow, and, far too often, we paid for our bravery with our lives.

Today, we are able to vote without fear of reprisal; without the looming shadow of death that stood at our flanks during the Age of Steam.

Thus, I enjoin you to exercise your right to vote – for me – for my re-examination and re-imagining of the Age of Steam, as I am nominated for Best Blog and for Best Multicultural Steampunk in the 2013 Steampunk Chronicle Readers’ Choice Awards.

Let’s bring some funk to the SPC Awards in 2013!

March 21, 2013

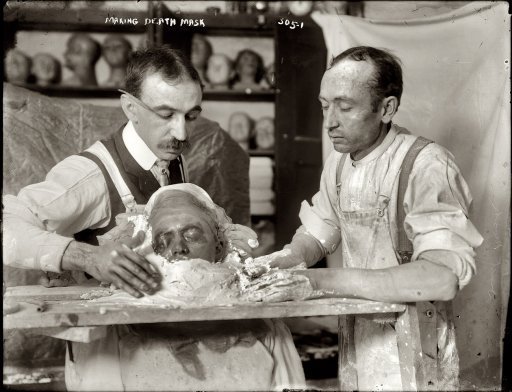

THE BEAUTY, POWER AND MYSTERY OF MASKS IN THE AGE OF STEAM, DIESEL & BEYOND!

THE BEAUTY, POWER AND MYSTERY OF MASKS IN THE AGE OF STEAM, DIESEL & BEYOND

Masks are powerful; mysterious; magical – seeming to weave a spell that creates a kind of unreality; a separateness from the everyday world.

Masks are powerful; mysterious; magical – seeming to weave a spell that creates a kind of unreality; a separateness from the everyday world.

Wearing a mask can completely change your persona – with your facial expression permanently fixed, you must focus on your body movement and voice, leading to the broadest, silliest clowning, the most intense of subtleties, or menacing stillness.

Masks can be as unsettling as they are beautiful. Expressionless, absolutely neutral masks are often spooky and masks without eyes or a mouth – a mask that hides the face instead of creating a new one – are eerie, yet compelling. Veils, shrouds and hoods pulled down low, effacing the wearer’s features, gives the wearer an undeniable authority and power – think Darth Sidious from Star Wars, or Altair Ibn-La’Ahad, from Assassin’s Creed.

Masks can be as unsettling as they are beautiful. Expressionless, absolutely neutral masks are often spooky and masks without eyes or a mouth – a mask that hides the face instead of creating a new one – are eerie, yet compelling. Veils, shrouds and hoods pulled down low, effacing the wearer’s features, gives the wearer an undeniable authority and power – think Darth Sidious from Star Wars, or Altair Ibn-La’Ahad, from Assassin’s Creed.

From a haircut to a pair of sunglasses, anything that transforms, or conceals, our appearance can influence not only the attitude of those who incorporate the change, but also of those who see them.

When director Jared Hess was in Mexico City casting the film Nacho Libre, a comedy in which the actor Jack Black plays a priest in training turned wrestler, he auditioned a number of real-life Lucha Libre wrestlers, who showed up wearing colorful masks.

Hess asked them to remove their disguises; they all refused.

Why?

Because the first rule of Lucha Libre – literally “free fight”, in Spanish – is that iconography is everything.

Because the first rule of Lucha Libre – literally “free fight”, in Spanish – is that iconography is everything.

“We learned very quickly that asking them to remove their masks was too much,” Hess said. “There’s a lot of integrity in that.”

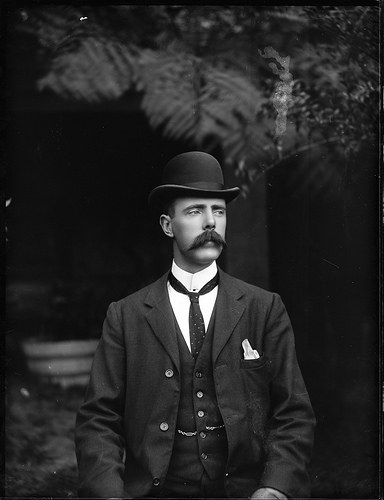

Masked wrestlers have been popular in Mexico since 1942, when the silver-masked wrestler, known simply as El Santo – “The Saint” – first stepped into the ring. Making his debut in Mexico City by winning an 8-man battle royal, the public became enamored by the mystique and secrecy of his personality, and he quickly became the most popular luchador (fighter) in Mexico. His wrestling career spanned nearly five decades, during which he became a folk hero and a symbol of justice for the common man through his appearances in comic books and movies, while the sport received an unparalleled degree of mainstream attention.