Erik Wecks's Blog, page 2

October 16, 2017

Gravlander: A Good Place to Start

For those of you who haven’t read any of my novels, Gravlander is a complete story arc and a great place to start. You don’t need to have read either Aetna Adrift, or The Far Bank of the Rubicon for it to make sense. I did that on purpose for a couple of reasons.

For those of you who haven’t read any of my novels, Gravlander is a complete story arc and a great place to start. You don’t need to have read either Aetna Adrift, or The Far Bank of the Rubicon for it to make sense. I did that on purpose for a couple of reasons.

First, this story wasn’t in the original concept for the universe which was a much more standard trilogy that revolved around Jonas Athena’s story. The universe as it exists today encompasses far more than just that story. Although the wars of the Pax Imperium are still the spine on which the universe hangs at this point, I could imagine a whole raft of stories that take place in either the past or the future that aren’t related to the wars.

Next, Gravlander revolves around a young woman and growing up, and as such, I think it will appeal to an audience that might not have been attracted to the Pax universe by the first two stories. I didn’t want them to be put off by having the book be inaccessible without reading the other two novels first, so I made sure that the book was self-contained with enough information to get you into the story but also not so much as to bore my other readers. (You know what I’m tired of explaining every novel—HeFAR.) It took a little bit of balancing to get that to work. Anyway, thanks again to my beta readers who made that happen.

The results have turned out pretty good. I’m really pleased with the early reviews from fellow writers. Jennifer Willis had this to say:

“Gravlander is an adventurous ride of medical science, cultural conflict, and good old-fashioned space battles, but at its heart it’s all about family. Jo’s journey from justified and misplaced rage to acceptance, forgiveness and even love is both gripping and refreshing. Wecks’ world-building is a thing of beauty.”

If you want to read the description and sample from Gravlander, you can go here. If you want to order a paperback or kindle copy, click the link below. And if you want to try out something of mine smaller than a novel, you can click the following link to get a kindle, ePub, or .pdf copy of my Pax short story collection Unconquered.

Get a Kindle or Paperback Copy Now.

October 14, 2017

Gravlander: Women as women

When I sat down to write a coming of age story for Josephine Lutnear, the hero of my new book Gravlander, I knew that I was going to have to write a story with a variety of distinct women ready to help her on her journey. Jo lost her mom at the age of four and really hasn’t had any female parental figures in her life since. For Jo there’s a craving that comes with the early loss, a kind of hole she wants to see filled. If Jo was going to find a mentor, it wasn’t going to be a man, so a cast full of women made sense for the story I was trying to tell.

This turned out to be a challenge but not in the way I expected. It wasn’t the cast of characters that surrounded Jo that I found difficult to write, but Jo herself. Jo starts the book as a wounded and broken young woman. She’s full of unresolved anger and self-pity. I found it difficult to put a story on the page that both allowed her to be emotionally immature and allowed the audience to root for her. I need to thank three women in particular for helping me get Jo ready, Jessie Kwak, Ronda Simmons, and my editor Crystal Wantanabe. All three of them let me know where Jo needed improvement. Jo wouldn’t have become a workable character without them. I am really pleased with the result.

As for the cast surrounding Jo, I appreciated that the story demanded that I build a cast that had a large number of significant women. I am the father of three daughters, each of whom has a distinct personality and view on the world. I want them to be able to find themselves in books I write. Representation matters. I’ve read far too many books and seen too many movies in which women might be present but they serve only as tools or props around which the men in the story orbit. Even if they are given a personality, it seems to be one in which their service to, or sexual attraction to the men around them is its defining characteristic. I was grateful to write a book that allowed a leading woman to exist without being bound by male sexuality or female servitude, particularly in a context of coming of age, which is so often associated with sex.

If you’re interested in finding more, you can read a sample on this page, or you can purchase the book through the link below.

Get a Paperback or Kindle Copy Now.

October 10, 2017

Preorder Gravlander Today!

My third Pax Imperium novel is finally here! Gravlander available today for preorder on Amazon with a lunch date of October 25th.

My third Pax Imperium novel is finally here! Gravlander available today for preorder on Amazon with a lunch date of October 25th.

Over the last month I’ve had the book out for some early reviews by fellow authors and the feedback has been really good. Here is what they have to say.

“Gravlander is a gripping novel that will captivate fans of classic no-holds-barred science fiction, with rollicking space battles, alien races, and exploration of new worlds, as well fans of character-driven studies of the human condition.” –Tammy Salyer, Author of The Spectra Arise Trilogy

“I immensely enjoyed the adventures of this young doctor as she grows and learns to combat the demons of her past. Jo’s story zigs and zags dangerously, ramping up to a gripping climax.” –Jason LaPier, Author of The Dome Trilogy

“Gravlander is an adventurous ride of medical science, cultural conflict, and good old-fashioned space battles… Wecks’ world-building is a thing of beauty.”–Jennifer Willis, Author of the Vahalla Series

“Gravlander is relevant and engaging. I loved the personal story of an imperfect protagonist who was simply trying to find her place in the universe…” –Will Swardstrom, Author of Dead Sleep

May 8, 2017

Sugarbug

Bloodied to his elbows, Alex Nowak stood from his work, inspecting the gut pile splayed upon the June grass. “Well, Gary, it had to be done. You know you had it coming, hanging around my crops and all. Don’t take it hard. Eventually, we all end up with our guts on the ground. Some of us just keep living afterward, that’s all.”

The early morning sun shone warmly now. That was good for the crops he had planted over the last few weeks. The sweat on his brow and still air promised rain, but who knew when that would come. Today. Or tomorrow maybe. Or this could be the beginning of the first long swelter of a Detroit summer.

The large buck had a good start on a set of antlers. Alex guessed it to be at least four or five years old, maybe a couple of more. It’s jerky then, he thought. Still, the back straps ought to be all right for a cure. The heart and other organs he would grind up for sausage for the smokehouse. He’d eat the liver for his dinner.

The work would mean a sleepless night keeping the fire going, but that was all right by Alex. He didn’t like to sit still. If he sat still, he remembered that he was the only living person within about four miles and that didn’t bear thinking about. Even before the disaster, there’d only been three other families on the block—the Winstons, the Degrazios, and the Smiths. Then a bad flu shaved 40% off the population of the US. Today, Detroit barely qualified as a town, let alone a city. Alex missed the hustle and bustle of when he was a kid. He used to race bikes with Brad Degrazio down the barely visible pavement. Now all the houses were either torn down or had crumbled to ruin. His was the only building still standing in the midst of the desolate quiet. Well, that and Mel Winston’s pottery shed, which he had commandeered as his smoke house.

When the flu hit, it was the Smiths that suffered the worst. Both of them had been nurses—left their kids orphaned. The Degrazios had taken them in. It wasn’t too long afterward Alex and his family had been the only ones left on the block. But that was a decade ago, and even his family hadn’t lasted. There had been one other couple that held out until a couple of years ago. The Stubman’s had lived a few blocks over, but they gave up when Del broke his ankle.

The noise of someone knocking led him to step out from behind the crumbling ruins of the Winston’s old place.

The young blond woman standing at his door far down the block knocked again.

Alex’s guts twisted in the cavity that bore them. He flinched backward as if someone had cut him with a knife.

A long heartbeat later he was sprinting out into the light yelling in the moldering street, waving wildly at the daughter he hadn’t seen in four years. Then she was running to greet him, jumping into him, arms wrapped around his chest like she used to do, almost knocking him to the ground. Gone was the little girl he’d left in Chicago with her mother. In her place stood a tall, young woman with full grown curves and all the eagerness and zest of a seventeen-year-old.

Holding his arms up so as not to stain her white shirt, all Alex could do was stand there and weep while his girl, his precious girl, rubbed her cheek against his chest.

“Daddy, put your arms around me.”

He couldn’t help but laugh. “I can’t. I’m all bloody.”

Tanner stepped back. “Daddy!”

Alex laughed all the harder. “I must look like a murderer.” Pointing over his shoulder, he continued. “I just gutted a deer in the woods behind the Winston’s.”

“A deer?”

“Yeah, I hunt. It’s what I live on. I hunt the whole neighborhood. I’ve even pulled a trout or two out of the creek.”

Tanner looked around as if she were seeing the area for the first time. From where they were standing, one could just make out the beginning of what Alex called the garden—but was a two acre field really a garden?

“Is that yours? You farm all that?”

Alex nodded.

And for a moment, Tanner looked at him as if she didn’t know him.

Alex smiled gently. “A lot’s changed since we moved away, Sugarbug.”

Not long after, Alex returned to his deer. Tanner went to the house to change into clothes more suitable for the day’s tasks. When she returned, he had sorted out the offal, placing the heart and bits he thought useful for sausage into a clean pail with a lid. The rest he buried.

A couple of years prior, he made the mistake of leaving a gut pile on the ground as an offering to the local coyotes in hopes they’d hang around and keep away the deer. They did, and all went well for a while, until Alex found a distinct group of K-9 prints leading away from a small patch of smashed and eaten melons. He spent the next couple of months chasing off the pack that he’d worked so hard to keep. He ended up shooting Fred and Bill before they finally got the message and moved on.

Alex waved Tanner toward the bucket while he picked up the deer by the forelegs and draped its heft over his back. His daughter let the silence rest between them and followed.

The time slipped gently, without pressure. He was so incredibly grateful to have his daughter by his side that he had to fight back tears as he marched the deer to the pottery shed turned smoker. He didn’t dare speak lest he ripple the waters and cause her to flit away. Besides, after four years of living with his own thoughts as friends, he wasn’t sure what to talk about, and if he waited, he knew she would tell him why she was here, when she was good and ready.

The moment presented itself later that afternoon.

“You’ve changed, Dad.”

In the midst of cranking the hand powered sausage packer, Alex didn’t look up from his work. “How so?”

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw his daughter shrug. “You seem way more mellow, like a lot of your worry is gone.”

“I don’t know about that; I worry plenty.”

“Maybe…”

“But I know what you mean. I think it’s the life. Things are a lot less complicated when you’re hunting and farming for a living. The next thing to do is right there in front of you.” Alex gestured to the strips of deer meat hanging from the ceiling. “And when you finish, you can look back and see that what you did seems important. That’s my food hanging right there.”

“I guess that’s a lot different than writing ad copy for products you don’t give a shit about… I can see the appeal.”

Alex felt his body start to release a load of tension he didn’t even know he had been holding. “I’m glad someone understands.”

Tanner just nodded, letting him concentrate on twisting off the next sausage.

Alex’ nose stung from the rising hickory smoke in the ten by ten outbuilding. It’s concrete floor and small size meant that it made the perfect smoke house for preserving the meat he harvested. He built a fire on the open floor and then spread it out enough to smolder. He’d thought about making some charcoal but had never gotten round to mastering the process. It was on his list of things to learn.

Outside, the black sky darkened the already smoky room. An occasional rumble told Alex that the storms weren’t too far away.

“I guess I have changed. It’s kind of hard to see when you spend most of your days alone.” As soon as he said it, he recognized that he’d caught the edge of the scab that he’d worked so hard to ignore, or maybe it was just having her around.

Tanner watched him deftly spin off another sausage from the end of the grinder. “You really like it out here, don’t you?”

“I do. I like it a lot better than Chicago. There’s no internet news to scare me and no social media to tell me everything I’m doing wrong, at least not when I don’t have the generator running.”

“There’s also no running water, Dad.” Not a hint of judgment. Just an observation.

“It’s a small price to pay for my peace of mind. I’m saving up for a well, and I collect rain water.”

Tanner sighed, contentedly. “And this is what you do every day? You hunt deer?”

Alex chuckled. “When I’m not pulling weeds, repairing the roof on the house, or chasing the crows out of the garden.”

“It must be a lot of work.”

“It is.”

“And you make enough to get by?”

“I sell some crops and things at the farmers market downtown. The truck still runs, so I can haul things down there. It’s enough to buy the things I need.” He gestured to the grinder.

“I bet it would be helpful to have another set of hands or two.”

The trap was sprung so deftly that he didn’t see it coming. All the hurt he’d worked so hard to keep in the past burst into the present. Alex’ throat tightened like a vice. “She made her choice. I let her go. I came home.”

“She sent me to say that she’s sorry and that she wants to come home, too.”

Unable or unwilling to plumb the depths of hurt and anger, Alex did what he had done for the last four years—he focused on the work of his hands. For a while, they continued in silence.

Having said her piece, Tanner retreated to tend the fire. The kid always had good instincts about how to handle her dad. She gave him space, waiting patiently for him to speak. It was a skill his wife had never mastered in all their eighteen years together.

The question blurted from his lips before Alex was sure that he wanted to know the answer. “How long did it last?”

“A couple of months. Not longer. The freshness wore off fast.”

“Were there any others?”

“Dad! You were gone, and you weren’t coming back!”

“Were there any others?”

“A couple. Nothing serious. Nothing that lasted. None of them measured up.”

Letting go of his work, Alex gripped the edge of the small wooden table, as his eyes glazed over with tears. “I can’t… I don’t know if I can…”

“She still loves you, Dad. She always has.”

“Then why?”

“Dad, you know why! So much changed after the flu. Everything. They shut down my school. They turned off the power, and the water, and the sewer. Everyone was gone, Dad. And mom’s a people person. She can’t… couldn’t be alone out here. You knew that. It’s why you eventually agreed to move to Chicago, where they still had lights, and theaters, and a place that felt safe, like it still had a future.”

Alex pounded on the table with both hands, his voice rasping. “That’s no excuse!”

His outburst brought an electricity to the room even as the wind outside began to blow.

Tanner refused to meet his eye. Instead she poked at the smokey fire with a stick. She wiped an eye with the back of her hand. Her shoulders slumped. “No, it’s not Dad. There is no excuse for breaking a promise. You taught me that.”

Alex turned to face away from his daughter placing his hands on his hips. “So what makes her think it will be different this time?”

“What do you mean?”

“Just what I said. She didn’t like it here last time. How is it that she thinks she will like it here this time? It’s even more isolated than before.”

Tanner sighed. “I don’t know, Dad. I didn’t come here with all the answers. The two of you are going to have to work those things out. But you have a car. She has some savings. I think there will be a way. I don’t think it was really about the place. It’s still not that far to the populated parts of town. She can join a social club or a writing group or whatnot. I think last time she was mostly scared. You both were. Everything was changing so fast.”

Alex rubbed his face. “I don’t know, Tanner. I don’t know if I want to forgive her.”

Tanner shrugged, her face betraying the pain he had caused her. “That’s your choice, Dad. She was wrong, and she knows it. I think you’d find that she’s changed, too. Maybe she understands herself a little better now. All she wants to do is come for a visit, just to see how it goes.”

Tanner stepped toward him and put her hand on his arm. “You know, Dad, you weren’t exactly the easiest person to live with in Chicago. You weren’t happy. Every day you came home from work angry. There wasn’t much of you left for us.”

“Well, I’m happy now.” Alex’ throat felt so constricted he could barely speak. “Maybe we were just never meant to get along. Maybe it was never meant to be.”

Tanner let go of his arm. She stood next to him chewing on her words for a moment before she spoke. “Dad, I don’t want you to let Mom’s worst moment define you. You know Mom went through a period of time where she hated herself for what she did to you, but she’s getting better. She’s free of it now. In fact, she’s better than I’ve ever seen her. You on the other hand… hiding out here and all…”

The rage was red hot. He turned on his daughter. “I’m not hiding! I like my farm. It’s my home.”

Tanner stood her ground, but kept her voice calm. “That may be, but you’re still hiding. You’re lonely, Dad, and it’s not Mom’s fault. It’s not about her, anymore. This is about you.”

“I’m fine!” Even as he said it, he knew it a lie, but his loneliness was precious to him, something he guarded from exposure even to himself.

Tanner’s jaw tightened. “People who are fine don’t name the deer they kill.”

Alex had slammed the door, stepping out into the downpour before he’d even realized what he’d done. The wind whipped rain soaked his left side in seconds. He deflated as the warm water soaked him, and then his shoulders heaved. He didn’t want to forgive his wife; she didn’t deserve it. She hadn’t in any way earned it, but Tanner was right, the bitterness with which he’d hoped to punish his wife had turned out to be a trap for himself. He’d known it for years.

For a while he stood there, allowing the rain to soak him, unsure of which way to go.

When the worst of it all had started to subside, he heard the door close behind him. He didn’t look back. Instead he tried to focus on the tap of each little drop as it landed on him. “You’ve always been a straight shooter, Dad. Mom needs that. Things have been rough in the last few months. A lot of the shine of the city has worn off for her, too. She might understand your perspective better now, if you’d give her a chance.”

It all hurt too much. His bitterness spoke to him gently. There you are, guts on the ground again. He just wanted to cut it all off, to send Tanner away disappointed and go back to his life, but he knew that path, and for a moment, it no longer held sway over him. “All right, she can come for a visit, but I make no promises. We’ll just see what happens.”

photo credit: Wayne Stadler Photography Nightmares We Dream via photopin (license)

January 25, 2017

Resist… Radicalization

On Saturday, 100,000 of us showed up at the Women’s march in Portland, OR to remind ourselves that love is better policy than fear and hate. I cried several times, just because it felt so good to know that I wasn’t alone, but as the week has gone on, I’ve been wondering what next. What is the next step to take in showing that I disagree with our president? I’m not sure I have an answer yet, but I trust that I will know when the time is right.

There’s a kind of Christianity that I like to call Amway Christianity. It’s a kind of “faith” heavy on the selling of the narrative and light on the substance. The GenX/Millennial version is heavy on doing good stuff—lots of charitable good works—but can be light on spiritual content. The Boomer version is all about personal morality. In this kind of Christianity an actual connection with the divine is almost unnecessary as long as you get the doing right. Whether that’s personal morality or good works, the important thing is to keep selling to yourself and others the narrative that Jesus died for your sins. It quickly becomes a kind of American multi-level scheme, where selling the process becomes more important than the product.

I was reminded of this kind of thinking this morning when I read an article on Wired.com about a federal judge in Minnesota who set up a program to deradicalize a group of Somali youths who had tried to join ISIS. The article starts by walking through the process of radicalization. Radicalization often starts with outrage, in this case at how the Syrian government treats its people. The injustice then leads to a focus on a need to act, to make a difference, a willingness to make sacrifices to make that difference. Eventually that need to act becomes so pressing that all else is lost or seen as less valuable—family, friends, values, and morality get sacrificed in the name of justice.

(I think this is what happened for many rust belt Trump voters. The economic injustices of globalization and the patent disregard by both parties led them to hyper-focus on Trump’s promises to the point that his deficiencies were lost in the noise.)

In the Wired article, Daniel Koehler, the expert used by the judge, argues—based on the limited science available—that the best way to deradicalize a skinhead or a potential terrorist is to remind them of their everyday mundane choices, to reengage them in life. If they used to like to take photographs, get them back into photography. If they previously did martial arts, get them into classes. The idea is to remove their obsession and ground them again in daily living—to make the everyday valuable again. The point is to slowly, over a period of years, help the radical remember and engage in other activities than their crusade. It’s a kind of reengaging with the substance of living.

The article challenged me that I need to resist the process of radicalization that is inevitable while living under the reign of Emperor Donald. The first days have been horrifying in their damage to our democracy. There have been so many attacks that even listing them is to go down a breathtaking rabbit hole that can only lead to fatigue and burnout. The tendency is to become so hyper-focused on the latest outrage that you feel the need to resist right now. Something must be done today to make it right.

The danger is that we forget to live the life we’re trying to protect, that we become radicalized and lose the values that generated our outrage in the first place. So my challenge to myself is to make sure that I don’t lose my life to the cause, because when I win, I want a life to come home to, a substance worth engaging. Without it, outrage might be the only thing I have left, and that would be a hollow life indeed.

So the next time that the latest outrage threatens to narrow your focus, to cause you to forget your life go hug someone, put down the social media, and live. Sometimes, that’s resistance enough.

January 17, 2017

Getting the Stakes Right

Nothing draws me out of a story like poorly done characters. It doesn’t matter how much technical gee whiz you put into the plot or how big your special effects budget, I don’t put up with stories that don’t have genuine feeling people in them, which is why I find The Expanse to be the best new science fiction series on television since Babylon 5. If you haven’t seen it, do yourself a favor and binge watch the first ten episodes free on Amazon Prime before the next season starts on February 1 on SyFy.

I am notoriously skeptical about television, which most often I find to be weak tea and boring. I usually wait until a series ends before I commit to watching it on Netflix or Amazon Prime. The Expanse has two things that give me enough hope to invest up front.

First, The Expanse is based upon a book series by Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck, who write under the name James S. A. Corey. That means one thing for the series: it’s got an ending. That is the number one prerequisite for good storytelling in any medium, including and especially television. To illustrate my point let me just list of a few shows, starting with Twin Peaks, X Files, Lost, and who could forget Battle Star Galactica. So what was the deal with Starbuck? I guess we’ll never know. Even better, Abraham and Franck are also producing the television series, so you can trust that their vision will be the guiding force behind the show.

That being said, science fiction is a notoriously bad genre for characters no matter the storytelling medium. So often the technical “gee whiz” or the coming destruction of humanity somehow cause story teller’s to populate their world’s with bland, unmotivated, and unchanging people. It’s even worse in scifi political thrillers like the expanse.

But that is what makes the expanse so great. Every character has a specific and personal reason for their behavior and that makes them all believable and worthwhile. From the character motivated by being forced to mercifully kill his own sister, to the character who grew up in a brothel, everyone, and I mean everyone, has a story behind their choices. That makes The Expanse worth watching because even when the overall plot is about a potential war between Earth and Mars, the stories told are always deeply personal.

I have to tip my hat to Abraham and Franck for making sure that each of these motivations shows up on the screen, often as the sole point driving a scene. It’s such a refreshing thing. Keep up the good work. I’m hooked.

January 9, 2017

Pax Imperium Update

It’s been almost two and a half years since I published The Far Bank of the Rubicon and over two years since I finished the Gravlander serial on GeekDad. I bet most of you have given up on getting the next Pax Imperium novel. Well don’t despair! A draft of the Gravlander novel was completed on December 13th, and I am currently editing furiously.

For those of you who didn’t read the serial, Gravlander covers the years between The Far Bank of the Rubicon and the next book in Jonas’ story, Athena’s Revenge. There’s around a ten year gap between the books, and while I was planning, I realized that Jo Lutnear would have gone from age fourteen to twenty-four in that timeframe. That’s a pretty big chunk of growing up, especially for a kid with a life like Jo’s. Gravlander tells her coming of age story.

If you read the serial, then the novel has a similar crunchy shell on the outside but takes the story in a whole bunch of different directions. The serial ended up around at 24,000 words. My current draft of the novel is about 118,000, with between 10,000 and 20,000 to add. I would bet that only 10,000 words remain from the original.

Here is the working description:

When she was four The Unity Corporation murdered Josephine lutnear’s family in front of her. Having escaped, Josephine became a political refugee and minor celebrity in those parts of the galaxy that opposed corporate rule. At the age of fourteen, The Unity launched a brutal war that destroyed all opposition and forced Josephine to go on the run. Having fled with the Ghost Fleet to wait for a time when rebellion would be ripe, Josephine has used the six years after the end of the war to become one of the youngest doctors in the fleet history, but fleet life hasn’t served her well. She chafes under a military system she did not choose. When the opportunity comes to escape, she eagerly takes an assignment as the medical ambassador to a group of genetic outcasts. Isolated and alone in a culture that has no place for her, Josephine must learn that she can’t become an adult until she understands what it means to be human.

So when will it be out? To be honest, I can’t say. If Gravlander has taught me one thing it’s don’t make promises about deadlines. I thought this story was only going to take me a year. Yeah well… not so much. That said, I am close. My first drafts are usually pretty clean, and I am finishing the last blocking pass right now. After that I want to walk through it and give it a voicing pass, to make the characters distinct and then its on to the final language edits. The other hang up is this, I showed the opening scene to a couple of big hitters in the industry at a writing conference and both of them were impressed. One of them asked to see the manuscript. Also, I’ve have a couple of agents interested in it, so they will definitely have a crack at it. So… there is a small chance that it could be a while. The most likely thing to happen is the agents reject it, and I am right back to self-pub.

However, if you’re desperate to get a look at it, I am going to be asking for a limited number of beta readers in the near future. I already have people asking but I have promised to give everyone on my mailing list a crack at the book. So sign up here to make sure that you get a chance. (You will also get a copy if you supported the Kickstarter. I haven’t forgotten about you.)

So will it be worth the wait? I hope so. The people who have seen bits of it so far think that it shows that I am becoming a far better writer, but I’m not you, so only you can tell me. I will do my best to make the wait as short as possible.

January 3, 2017

A Field Guide to the Thinking of an Evangelical

So I finished up the body of what turned out to be a rather long re-introduction of my blog, and I’m really not sure why I wrote it. I’m not usually one to fly the flag of my faith in my professional life. Oh I think it’s there, hanging around the edges of my science fiction. I’ve written a couple of short stories that you can find on this site that are blatantly message driven. I also don’t imagine the future as a world free of religious concerns. However, when I sit down to write a story, I have yet to write an overtly religious lead, or side character for that matter, and if I were to do so, I’d probably want to make that character a pagan or some kind of future religion before I made them a recognizable Christian.

And maybe that is exactly why I wrote this essay. If you hang around Facebook long enough you will probably guess that I am a Christian of some ilk, and when so many evangelical Christians openly support a man who brags about sexual assault—if only because he promises them Supreme Court Justices—I felt the need to make sure that my audience understands that I abhor that thinking. I want to stand up on the roof and shout “I’m not one of them. I think they’re part of the problem!”

But there’s a little more too it than that. I may believe their thinking to be wrong-headed, but if I stand on the roof of my own soul, I can see that distant country from my house. I know the road that leads there, and in a different time, I might have walked there too.

So without further mucking about, here’s a bit of my journey to no longer seeing myself as one of them. If you’re a secular person who finds yourself confused about how a Christian thinks, it might provide an interesting field guide to the inside of an evangelical Christian’s head.

A bit about my past…

I was raised in a traditional, conservative Christian household (back then we would have said fundamentalist but that word changed and evangelical replaced it). Paul (one of the writers of the Bible) says that he was a Pharisee of Pharisees, in other words, that he was the most religious among the already extra religious.

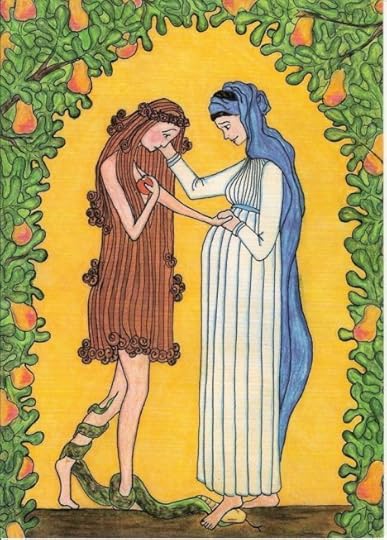

I’m not a Catholic but I resonate so strongly with this image that it seems a great representation of my thoughts here.

I can relate to that statement.

I come from a long line of proud evangelicals. My great-grandfather served on the board of Multnomah Bible College and helped found Central Bible Church with John G. Mitchell. (For those of you not familiar with Pacific Northwest Evangelicalism, think of John Mitchell as a regional Dwight Moody kind of character, although a couple of generations later. Still lost? He was big stuff, at least in these parts.)

When I was born, I was part of the fourth generation of Wecks’ to attend Central Bible church. The connection between the Wecks family and CB lasted for almost eighty years. I have to admit that last spring I felt an extra bit of sadness as I sat in the fellowship hall just off the sanctuary and realized that my grandmother’s memorial reception would be (for now) the very last Wecks family event at Central Bible. That church cared a lot for my family—and for me.

I attended there for the first four years of my life and as far as I can tell, I was a bit of a celebrity—at least among the Sunday school teachers. At my grandmother’s funeral, I still heard from one of them about how much she enjoyed having me pray in class. The reasons for this were varied. There was of course my name; it was a big family and well respected in the church. Then there was the bright-eyed creativity from my mother that gave me a knack for getting attention. Combine that with my full sentences at eighteen months, and I soon learned that I could get lots of kudos by praying and having the right answers.

Do you see the problem yet? No? Let’s look at it from another angle.

A bit about theology…

There are many forms of Christianity—even some forms that would call themselves Christian that I would not call Christian. The form of Christianity that I was raised in proposes that human beings were once in a state of perfection. They fell from that perfection through an act of rebellion, traditionally eating of a fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. This Christianity proposes that something happened at that moment that caused a rift between human beings and the creator. It is said that God is too perfect to live with our imperfection. He requires of us that we become “holy” like him before he will accept us. He has in essence turned his face away from humanity until such time as humans can be made worthy again of his presence. Without some kind of divine intervention human beings are doomed to an afterlife without a relationship with our creator—an afterlife of eternal loneliness and suffering. Jesus—and in particular his willing death on the cross—is said to be the means by which we can again become worthy of relationship with God. The blood of Jesus is said to wash away the sins of believers allowing God to once again dwell with them. Also, Jesus is thought to be God living as a human, so his willing death on our behalf proves that there is no depth to which God wouldn’t descend in order to bring us back into relationship with him. It is the proof of his love. All we need do is accept this transaction written in God’s blood as the means of our relationship with God. A fitting and proper response to receiving this love is to set out to live a similar life of self-sacrifice.

This was the theology that I was taught at Central Bible. It was the air that I breathed, the food that I ate as I was first learning to have a sense of self, and contrary to what most adults believe about kids, I understood it, and I believed it with all my heart. Even as a little child I set out to live it.

Do you see the problem yet?

Putting it all together

I don’t want to walk you through all the strang and durm that led to the eventual breakdown of my belief in this vision of Christianity. Needless to say there were a million different moments. It’s been a forty year process. One such moment was certainly reading a bit of Nietzsche in college. His question of why God would need to pay a debt that he himself created really stuck with me and made me wonder about the same question. Just cancel the debt and call it good. I never could shake that. Oh I did for seasons—talk about integrity and all—but if you think about it, it doesn’t make sense.

Eventually, I came to my own articulation of the problem. It goes something like this: the Christianity that I was raised in proposes that God holds the gun of hell to my head and says, “Love me or I’ll shoot.” By any reasonable definition, such behavior isn’t love—not even from a Creator. I think we can dress it up in a million different ways, but when you parse the message of much evangelical Christianity, it boils down to something like that. God is too perfect to be with you and unless you choose to love him he’s going to beat you with his club for all eternity. It’s your choice—love God or suffer. Oh and remember, God loves you.

I think it’s really reasonable for people outside of Christianity to wonder how this whole edifice doesn’t collapse under its own weight—and maybe that is what is happening right now. Church attendance is taking a rapid nosedive in the last few years. When Christian social scientists (Barna) went to survey who was leaving, they found out that it was people from the center not the fringes. I think lots of us are waking up from this bad dream.

It’s a bad dream made all the more difficult by its practice. The promise is that Jesus has made a way by which we can experience a sense of rightness within ourselves because we are now restored to a proper relationship with God. However, this type of Christianity proposes that our experience of this sense of enoughness is wholly dependent up on our willingness to embrace the transformation necessary to remove our basic inadequacy caused by our rebellion.

You have to perform to get the benefits—so you go to church, you pray, you read the bible, you become a “home community” leader, and you do stuff for God, like holding homophobic signs or feeding the poor depending on which you think God is asking you to do. I dare say that most Christians go their whole lives trying to live out this horrible notion that they start life as “not enough” and that they must transform their whole selves—personality, talents, desires, and everything else—in order to be acceptable with God.

For my secular friends, I hope that explains the schizophrenia of modern American Christianity. One moment they’re doing good stuff, the next they’re being hateful and trying to control what you do with your body. If you wonder how a person can stand on a street corner claiming that God is love and at the same time hold a sign that says “God Hates Fags,” look no further than this belief. If you are wondering how a Christian university president can convince himself that his student body needs to be well armed, look no further. If you’re wondering how so many evangelical Christians were willing to give a pass to a candidate who bragged about his power to sexually assault women, I honestly think it comes back to this—evangelical Christians have to be right. Their whole sense of security is based on right belief and right performance. For evangelicals, enoughness might be technically settled by the cross but the experience of enoughness is wholly conditional and dependent on our good behavior and willingness to transform ourselves.

Even as a small child, I was never enough. It didn’t matter how many times I prayed, how many kudos and gold stars I achieved in Sunday School, I never measured up. I was gifted with the ability to try—I memorized all the right verses in Awanas and led my friends to accept Jesus. Yet no matter what I did, I always felt inadequate. I was—am—ashamed of me. (I’m working on that. Thanks Brene Brown! I owe you one.)

Looking back, I have come to believe that my early church experiences both supported this sense of inadequacy and gave me the means to cope. After all, God was in the business of making me enough—making me worthy of being in his club. I developed what I like to call an annihilationist theology. I learned early on that the core me was no good. My heart was untrustworthy—”desperately wicked” as the phrase goes. It had to be completely replaced by God. He was, of course, going to replace it with someone who would want to do something important for him—like be a missionary. That sense of self carried me all the way to a year of bible college at the “family” school. Thank God it didn’t carry me into the mission field!—as it does for so many.

I believe if you look deep enough you will find in almost every Christian a deep experience of inadequacy—actually I think it’s a plague that haunts almost all humanity, but that’s a different post.

Giving Up…

I’m not sure why I never had a definitive break with my faith. There have been many times when I wished I could just stop believing and go on my merry way, but I have never been willing to make that move. Many of my writer friends have. I’m lucky to be surrounded by evangelical expats. I love those people.

I think a lot of why I stayed had to do with my family. For all its many faults, my branch of the Wecks family was a relatively loving place to be a kid. My parents too. They did the best they knew, and I think I understood that. It was at least enough for me to continue to hope that there was some way to square the wheel and find a way out of my need to perform for a God who claimed to love me but also held over my head eternal damnation and temporal blessing and used them as weapons to enforce his will. Also, I had a lot of beautiful experiences in evangelicalism, many of which I would count as encounters with the creator, so I was never really able to treat those as a mere figment. I’m still not sure why I never had a definitive break with my faith. Perhaps I still will, but I don’t think so.

For me change began when a Christian counselor friend introduced me to a book called ACT on Life not Anger. It came at a point of real exhaustion in my quest to get my life right enough for God, and I was open to new ideas. If you’re a secular person it might be readily apparent that such a theology could easily create judgmental and angry people who seek to control their own feelings of inadequacy by controlling everyone around them. Yeah… there’s me at my worst, but when you stand inside that system, it’s not at all apparent. I’m working on it.

The book was an eye opener because it proposed that struggling with feelings of anger would never make them go away, in fact it would make them worse. Instead it argued that the best way to handle your feelings of anger is to practice non-judment toward yourself and others.

So I don’t know how many of you remember Jim Rome the sports talk guy? (Yeah, I know. It was a phase.) Anyway, whenever someone would call his show and complain about referees or coaching, he would just reply, “scoreboard.” In other words all excuses aside, your team didn’t score enough points to win. I’m a big believer in the “scoreboard” theory of life. If you are wondering about whether something is good or not, just look at the scoreboard. If it’s effective, it’s good. If it’s love, it’s from God. If it’s not love, it’s not from God. It’s pretty simple like that. (Oh we can debate what is love and what is not, but that’s for a different post.)

So I bring this scoreboard theory up because as silly as it may sound to many of my secular friends, it was actually quite a revelation to me to find out that when I worked really hard to replace my judgment with compassion, it made me a better husband, father and friend. It worked. I was more the person I wanted to be when I didn’t judge. I was more loving and so to me more Godlike in my behavior.

However, this created giant cracks in my concept of God. Up until that point, my Christian practice had largely been centered around judging myself and trying to be good enough to experience God’s blessing. At the center of that practice of life sat a judgmental God who held himself separate from fallen humanity because of our rebellious and desperately wicked hearts. Yet, all the judgment I had toward myself had never helped me be a more loving person. In fact it had created the opposite effect. Now I was finding better love through giving up my judgment. So if I follow the “scoreboard” theory of life, it follows that something was desperately wrong with my intellectual concept of God. Judgement and love no longer worked for me. I needed something new.

What do I believe now?

(So thus far, I’ve only expressed the dilemma. That’s a much easier thing for more of us to agree upon. Moving forward, this gets a little more personal. It’s my attempt to make sense of life. Read it not as an attempt to convince you of anything—could I?—but rather an expression of my way of making life work within a Christian framework. To me it shows a way of thinking about Christianity that allows space for a truly non-judgmental approach to life and thus a life led by compassion rather than pride and hubris.)

It might seem like this was the moment when I would abandon Christianity all together and strike out on my own, finding God in the milieu of believism that makes up modern American spirituality, but actually the recognition that my concept of God was flawed had the opposite effect. It sent me back to try and understand anew the faith where I had experienced God despite it’s very ineffective theology and practice.

After my discovery of the effectiveness of non-judgment as a way of life, I spent a lot of time wondering about two things. First, once I started replacing judgment with compassion, it became instantly clear to me that the idea that I was somehow fundamentally flawed would no longer do. It was time to leave that nonsense behind. I was enough, worthy of love just as I am. (The same counselor who introduced ACT on Life… pointed me to Brene Brown, whose book Daring Greatly was highly influential here.) Many of my actions might violate my values and be ineffective in creating a loving planet but seeing myself as in need of annihilation was not the answer to this dilemma.

That left me wondering what exactly was God trying to communicate with the story of humanity’s fall? If we’re OK as we are in his eyes why the Garden of Eden story? Also if I wasn’t somehow in need of a magical transformation by Jesus’ precious blood, what was all that death nonsense about? Answering those two questions became essential if I was to transform the faith I had been given as a child. Without answers I felt that I would be forced to conclude that God could not be found in Christianity at all.

The answer to the first question came from a simple, careful reading of the Genesis text on the fall. As I said way back at the beginning of this essay, the Christianity I was raised in proposes that there is something so flawed with us that God must hold himself separate from us until we can be made worthy of relationship with him. However, I would propose that the Adam and Eve story says just the opposite. It is we who hold ourselves separate from God, trying by any means to prove our worthiness. After they ate the magic fruit, Adam and Eve hid, sewing fig leaves to cover their genitals. It was God who came to the garden begging them to come out of their hiding and lean on him. If death became a necessity for us after the fall, it isn’t because God cannot handle our sin, it is because we cannot consistently handle the perfect love of God without being ashamed of our imperfection. In this vision of Christianity, shame isn’t the proper response to the bitter broken state of our heart, it is the problem. Shame is the knowledge of good and evil internalized. It is the thing which keeps us going to our own resources and trying to be enough on our own instead of being vulnerable to the perfect love of God.

(For those of you playing along at home, you might hear a little bit of Rousseau in this—I see ennui as a form of shame, a sense of inadequacy. I’ve always liked the opening of On the Origins of Human Inequality as a statement of humanity’s condition, and Rousseau himself saw it as a statement of theology, dedicating the essay to the city state of Geneva, where he had been banned for heresy. I have read that he hoped that the essay would put him back in the good graces of the church there. Needless to say the calvinist theologians of Geneva were not persuaded. However, I think he provides a pretty good foundation for thinking about the psychological dilemmas most human beings enact. He seems to describe the fall quite well. The rest of human experience—maybe not so much.)

The second question, the one about the cross, was much more difficult to answer. In the evangelical notion of Christianity, Jesus blood is necessary to cleanse us because in our current state we are so dirty that a holy God cannot abide our presence. For a long time when thinking of the Cross, I felt it inevitable that I would be forced to conclude that Christianity taught that God needed blood sacrifice to get rid of his anger. Yet such thinking was so opposite to my own learning on anger. Anger only truly goes away when I willingly accept the hurt caused by another. Anger diminishes when I accept that I will never be paid back. This acceptance allows me to live in this moment and do that which is worthwhile in the present, instead of dwelling in the suffering of the future or the past. Acceptance and non-judgement allow me to be a compassionate person. As I started to live out this new thought, I kept being struck by how opposite it was to the narrative of God. God got paid by Jesus dying and shedding blood—vengeance was had by God on Jesus, and I escaped. He got to stomp his feet and demand retribution. Yet here I was so clearly learning a different and better way, that had real effects for good in my life, and I truly believe it was God himself that was teaching me this new way.

Let me start by saying that the idea of a God who is so offended by sin that he won’t dirty himself with it seems to me contrary to all evidence in the Bible. If you read the Bible you will find that God is continuously trying to interact with humanity and it is we who are continuously pushing him away—Moses at the burning bush, Israel at the Mountain of God, the whole book of judges. I could go on.

This one really hung me up for a while. If the cross wasn’t about payment to calm down an angry God what was it about? I did some reading and thinking. I found the theologian NT Wright to be particularly helpful on the topic.

In the end, I think that the simplest answer is the best. If we take seriously the notion that our human ability to self-reflect combined with an internal knowledge of good and evil create a paralyzing shame, an open relationship with a perfectly good God becomes impossible. No matter what God says, we cannot expect him to love us unconditionally nor can we be vulnerable to him. He is too good, to perfect and we are doomed to always be afraid that our next imperfection will finally be the one in which he rejects us. So instead we bargain, or we hide, or we look around and conclude he doesn’t exist. The only way to change this dilemma would be for God to prove that he will love us no matter what we do—and this to me is the magic of the Cross. It is one thing to say that I will forgive anything you do to me, it is another to show it, to perform it and make it real. Jesus—who Christians believe to be God incarnate—died to make real the truth that God will forgive us no matter what. It wasn’t just a metaphor or play acting either. In forgiving the humans who killed him while on the cross and treating them without judgment or anger, God made real something that wasn’t real up to that point. I believe there is real magic in the words, “Father forgive them for the don’t understand what they are doing.” In the history of the world there has never been a stronger magic spell than those words. They did real work, demonstrating that no matter what we do, we are enough in God’s sight. He will never reject us or judge us. All judgment was used up on the cross. In this way, I have come to believe that Jesus did open a door to God that had been closed previously, but it was not God who closed it, it was us. God never needed to be convinced to accept us warts and all. Instead it was us who needed to be convinced that he could accept us warts and all.

So where does that leave me? I still think of myself as a Christian but not an evangelical. I love God to the best of my ability and I am learning to see myself as enough, despite my real imperfections. I am trying to replace all my judgement with compassion—and I have found Buddhist thinking important here. Overall it seems a better foundation for compassionate living. It also seems to make much better sense of the Bible than evangelicalism and that for me is important.

So will anyone read this blog post? I don’t know. I guess I hope that some of you might be interested in what goes on in the noggin of someone who creates the stories that you love. But read or not, this is my way of shouting, I’m not like them! And that seems to me to be all the more necessary in the coming years. Love and compassion will win. They already did.

December 21, 2015

Why it matters…

Tonight SpaceX made history. It landed the first stage of a rocket that had delivered a payload to orbit. It’s the first time ever, and it’s a big big deal!

Space is hard and expensive. Most of that expense comes because every time we go to space we throw the rocket away. Think of what it would cost if we threw away an airplane every time it flew. On the launch broadcast they said it would mean that it cost about one-and-a-half-million dollars to fly across country. If we can learn to reuse rockets by landing them regularly, we can make space flight much much less costly, and that will let us consider such things as a permanent moon base or a colony on Mars.

The problem is that its really, really hard to land a rocket that goes straight up. Jeff Bezos and Blue Orbital did that recently, but that is child’s play compared to landing a rocket that has taken a payload toward orbit. Why? Because orbit requires moving sideways through the atmosphere at around17,000 miles an hour. What Bezos did is much more comparable to landing your Estes model rocket in your back yard than it is to what Elon Musk and Space X did tonight.

Now the first stage doesn’t get all the way to orbital velocity but it does do a significant chunk of the work. Then it has to turn around burn back the other direction to get back to the landing area and then burn to slow itself and land. That’s impossible, or it was until tonight. Tonight Space X made the impossible possible. History will look back on this day.

It’s easy to forget the thousands and thousands of hours poured into making a marvelous machine do something outrageously cool. That’s why you need to watch the video below as the team at Space X celebrates the fulfillment of their hard work. (I started it in the middle, right near the landing, but the whole thing is worth watching when you have a few minutes.) Enjoy!