C.E. Santana's Blog, page 4

August 14, 2015

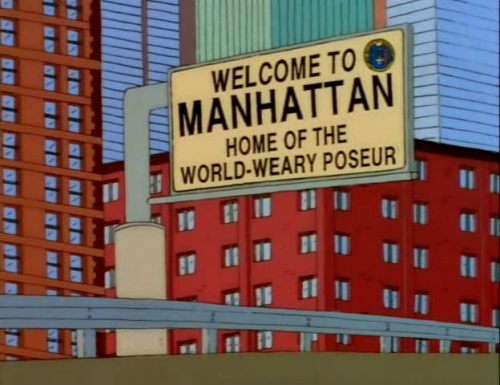

nevver:

Signs of Springfield

August 13, 2015

bonjourzhang:

The Wind Rises

August 12, 2015

New Short Story: Supreme

If you drive up Old Woman Spring Rd, make a right on Reche Rd in the town of Landers, make a left on an unnamed dirt road, and drive for four miles, you come across a church called The Supreme Church. It’s a small, all white adobe structure with a curved roof that resembles a spaceship. Built by William Bright, the preacher, a tall strong man with dirty blonde hair, a permanent goldish tan, and a boyish face, the church holds maybe fifty people, and it’s always empty. The giant white cross that stands near the road is taller than the church, and if one somehow finds themselves driving on the dirt road, one sees the cross and not the church, which is hidden behind a cluster of boulders. If the church had been painted tan, and not white, it could easily camouflage in its surroundings. The people of Landers (there isn’t many) and the surrounding towns know of the church, but like good Americans, no one asks questions or bothers their neighbors.

Deputy Sheriff Letterman has passed by the church many times. On his shifts, which used to be during the day and are now in the graveyard, he sometimes drives up there and parks his patrol car a few hundred yards away from the cross, and stares at it for hours at a time, until his shift is over or he’s called to disrupt a bar fight or check on a domestic violence call. He picked that spot to post when he first started to work the graveyard shift. He was driving around, bored, and in the light of the moonlight and the purple hue of the sky, he saw the giant cross, appearing to be hovering in the air. He stopped his car and stared at it, before being called back into town. Now, whenever he gets the chance, and it’s often, since getting back onto Rt. 62, where the Sheriff’s station is located, only takes 10 minutes speeding, he’ll drive up there and stare at the cross. Sometimes a shooting star zips through the sky above the cross and Letterman wishes this meant something, but he isn’t sure what. Letterman’s church, the one he attends on Sundays, is in Joshua Tree, and it’s packed on Sundays with the known faces of his community: other cops, business owners, judges, public service workers, teachers, and so on. He’s never seen anyone at The Supreme Church but he doesn’t ask questions. As long as Letterman is never called to check something out on the ten acres of land William Bright built his church on, Bright can do whatever he wants on his property.

Which is why is when he is told to go up to the church to notify of a death he is alarmed. He’s in the first hour of a double shift, drinking coffee at his desk. It’s 7 AM.

“You’re always up there,” his captain says. “Maybe you can make sense of who’s up there.”

“I’ve never even seen anyone up there,” Letterman responds.

“Well, it’s the only address we have for the father of the deceased. Go up there and see if anyone actually lives there.”

✞

On the drive there, Letterman thinks of what to say. Notifications of death are hard to begin with, but not knowing who he’d be talking to, worries him a bit. He thinks of asking for backup, but that sounds silly. But he can’t shake the feeling that something strange is about to happen.

He goes over the facts of the deceased:

William Bright Jr., known as Billy, a local kid with numerous run-ins with the law, mostly for drug related crimes, entered a motorcycle garage yesterday afternoon and attempted to trade in an ounce of meth for a used motorcycle. When the men at the shop, part of a biker gang called The Desert Devils, searched him and found more drugs, a fight broke out. Billy was stabbed multiple times. The bikers escaped. Someone walked into the shop to inquire about parts, found Billy bleeding on the floor, and called the cops. Billy confessed to the man the bikers had robbed him for about a pound of meth before passing away on the scene. His last words, according to the man, was gibberish about a movie star named Clara.

“She’s a movie star, I see it!” Billy had said. According to the man, he wasn’t in agony. He was smiling. “Clara the movie star!”

It had already been an eventful day for Letterman. A couple hours earlier he responded to a 415 at Old Brien’s house, a house well known by the sheriff’s. But a 415? Letterman, had thought. Old Brien’s is in the middle of nowhere. Who would call the cops on a disturbance complaint? When Letterman arrived, he found a naked girl sleeping in bed. Under her pillow he found a few bags of meth. Nothing out of the ordinary, sure, but who called the cops? It all made sense now. The girl’s name was Clara. Her boyfriend was William Bright’s son, Billy.

Letterman drives up to the cross and turns right onto the property, up to the boulders that seem to connect to the church. Stopping the car, he takes a deep breath, then walks towards the structure. Doing a couple laps around the church, he attempts to see if he notices anyone inside. Just as he is about to knock, he hears a voice from the side.

“You can come in through here.”

It’s a woman’s voice. Letterman follows the voice to a blonde woman. Her hair is long and flows freely over a loose white blouse and blue jeans. Letterman walks up and introduces himself.

“I know who you are.” The lady says. “Come inside.”

Letterman is led through a side door, through a dark hallway, and down a staircase. At the bottom of the stairs, the lady opens one of two large steel doors. Nothing can prepare Letterman for what he sees: a huge open white space, with natural light flickering through glass windows on the roof. The space is pristine clean, like a lab. There are mostly adults in their twenties and thirties, but also a few teens and small children. The children and teens sit on the floor on a rug, drawing and writing on the floor. It must be part of a class, Letterman thinks. The adults meditate in circles, separated into small cliques, like a high school lunchroom. No one looks at Letterman or stops what they’re doing. There’s an eery silence. There must be thirty-five people all together, but there’s an organized hush, like a library. Or a church, Letterman realizes. People are worshipping.

Letterman is led to one specific clique sitting to the farthest corner. A man stands up and the lady takes his place in the circle.

“Hello, I’m William Bright,” the man says. He smiles. Looking into his eyes, Letterman loses his focus for a second. His crystal blue eyes stare at Letterman so deeply it’s as if they’re staring deep into Letterman’s mind. Letterman doesn’t feel uncomfortable or tense. He simply forgets why he’s there for a second, forgets who he is or his own problems. His eyes are so blue, it’s almost as if looking at water, at his own reflection.

“You’re Deputy Sheriff Letterman,” the man says.

Letterman snaps out of his trance. “Yes, sorry. How did you know?”

William glances down at Letterman’s badge.

“Oh, yes, of course. That’s silly of me.”

“What can I do for you?”

“I’m sorry but I’m here with unfortunate news. It’s about your son, William Bright, Jr.”

“He passed.”

“Yes, tragically.”

“It’s quite alright. I knew for some time now.”

Letterman finds this odd but doesn’t say anything. Instead, he continues with the routine. “I’ll need you to come down and identify the body.”

“I’m afraid I can’t do that,” William responds.

“And why is that, sir?”

“I haven’t left here in years. I’m sure there are ways to get around identifying the body.”

“There may be, but how about what to do with the body? You don’t want to make any funeral arrangements?”

“No, we don’t believe in funeral arrangements for the physical body. In our religion, the body means nothing. Someone who belongs to our religion, doesn’t die in the traditional, human way. There are no traces of the human body when one dies.”

“I’m sorry I’m confused. I’m Christian, and I’ve never heard of anything like that in Christianity.”

“Well, what makes you think we’re Christian?”

Letterman is confused. “Your cross, of course.”

William grins. “Let’s take a walk.”

William leads Letterman through a long corridor. It reminds Letterman of a corridor in a secret underground military base. At the end, another set of steel doors are automatically opened as William and Letterman approach. They enter a giant bio-dome. Letterman realizes this must be the cluster of boulders outside. They’re a camouflage for this dome. There’s plants of all types. Exotic plants Letterman has never seen. There’s flowers of all colors. Huge flowers bigger than Letterman. There’s plants with leaves the size of cars. There’s small plants that wiggle around in harmony like a school of fish. He does recognize marijuana plants. Letterman stops and stares at them. Not as an officer of the law, but as someone who sees something familiar in a surreal world.

“Almost all the plants here are extinct or near extinct plants from the Amazon jungle and other jungles around the world. All these plants tell the secrets of the universe. These plants are our God. There’s a plant that provides all the nutrients we need, just off a single seed a day. There’s a plant that when ingested, makes us immortal. That is, no ailment can kill us, only fellow man. The tribes that knew of this plant are all dead. Not from sickness but from man. I’ve lived here in this dome for years. The cross is simply a disguise. So no one bothers us. And no one does. They see a cross outside and people leave us alone. Sometimes someone may walk towards it, seeking something, but they leave once they find out no one is going to answer their prayers. The desert climate helps with that too. No one can survive outside too long before giving up.”

Bright pauses for a second to examine the growing blue buds of a long stemmed purple plant. Letterman has never seen anything like it. The colors are so psychedelic and lush it’s as if the plant was illuminated by a black light.

Bright continues, snapping Letterman out of his thoughts.

“Billy was raised here, with his mother. His mother and I had a disagreement, like humans do, and she left, taking Billy with him. She raised Billy telling him stories of how I was a crazed cult leader who worshipped aliens. Which is semi-true. These plants are somewhat alien, in a sense. I don’t think they were native to earth. I think they were brought here eons ago by an alien source. Their magic is too powerful for what grows on earth. What grows on earth are simple compounds. They feed man or they kill man; very few enlighten man. I rescued Billy’s mother years ago. She came here seeking salvation from her demons. I housed her, fed her, loved her. But she wanted out and I granted her out. Facing the problems of the world, she was bitter when she wasn’t allowed back in, and strayed my son on a different path.”

“Why didn’t you let him back in?” Letterman asks, enthralled by the story.

“He was already gone.”

✞

Letterman drives back to the station in shock. He doesn’t quite know what to believe. Alien plants that make us immortal? A religion where bodies don’t die traditionally? William Bright implying he knew Billy was already dead for some time? It’s all too much to take in. Letterman feels exhausted. When he gets back to the station he can barely focus. His captain notices this and asks if he’d like to go home. He’s been working double shifts for almost a week straight and the toll of work, the heat of the desert, the constant alertness one needs as a cop, is getting to him.

He lives ten minutes up a dirt road from Twentynine Palms, south of a large military complex serving both the Navy and Marines. He lives in a one bedroom, low level house with his two dogs, both tan labs. He used to have a third, a black lab, but he disappeared. Letterman thinks the dog was killed by coyotes. Besides the tragic loss, Letterman likes his living here, alone. The nearest home is about two miles away. He used to be married but his wife left him two years ago. She got bored of desert living and moved to Los Angeles. Letterman gets bored, too; but if he needs companionship, he’ll drive to a bar near the military base and drink with the military men —men who share his outlook on life; men who love their country; men he occasionally takes to an always vacant motel on Route 66 to sleep with them.

That’s the other reason his wife left him. She suspected him of cheating so she hired a private investigator. The P.I. brought back photos of Letterman with a young man in a military dress uniform outside a rundown motel. She was in shock. When she confronted him, Letterman said he and the man were going over a top secret project and needed privacy. She didn’t buy it. In the photo, Letterman is seen carrying a bottle of whiskey in his hand. When she left him, Letterman spiraled downward. He started drinking heavily and his job suffered. They moved him to the graveyard shift, when there was less work. It was worse for Letterman. The reason he found The Supreme Church was his need to disappear. With a personal bottle of whiskey, Letterman spent hours parked in the desert, one hand on the bottle, the other hand on his gun. The night he saw the Supreme Church’s cross was the same night he was about to finally pull the trigger. Then he saw it. It glowed under a full moon and the millions of stars visible in the desert sky. Ever since then he stopped drinking while on the job. He still drove up to the church, to sit in his car under the cross, but now he kept his gun in the holster.

He still fought the urges to go into town, have a drink at the bar, spark convo with a drunken Marine, convince him they should take a ride together —to shoot their guns.

It’s one of those nights. Letterman tries to masturbate the feelings dead but their persistent. So he gets in his car and begins to drive south, takes a right on TwentyNine Palms and heads towards Palm Springs. Even though he’s been living in the San Bernardino County his entire life, he’s never been to Palm Springs. That’s where rich people live. In their mid-century vacation homes, and their immaculate, lush golf courses where it never rains. But he knows about Palm Springs. He knows there’s bar he doesn’t have to get men black out drunk to fuck them.

There’s a colorful flag outside a bar. It looks like a normal dive bar but once inside there’s electronic music playing; there’s air conditioning and the scent of expensive candles. He thinks it’s rather cliche of gay people, but then it’s probably just the comforts of the wealthy, he thinks. He orders a beer at the bar. There’s men everywhere but no one bothers him. He’s an outsider —they can smell it on him. His haircut is too high and tight; his pants too straight leg. He oozes cop. Or that’s what Letterman thinks at first. After his second beer, the bartender starts opening up, then a guy sitting to his left, then another guy across the bar comes to sit next to him.

“Larry,” the man says, reaching out his hand.

“John,” Letterman responds.

“Pleasure to meet you.”

Letterman nods. Takes another sip of his beer. It’s cold and refreshing. It comforts him. So does the music, and the smell of wood and leather and lavender from the candles.

“It’s nice here,” Letterman says after a long silence.

“Yeah, it’s your first time here?” Larry asks.

“Yeah.”

“Where are you from?”

“Over the hills north. Near Joshua Tree.”

“Oh, nice! I go to Joshua Tree all the time.”

“Yeah, it’s not really like that. It’s not a desert paradise where I’m from.”

Larry nods. As to say, I get it, we don’t have to talk about it. Letterman senses an awkward silence and breaks it: “How about yourself?”

“I live in L.A. I have a house here. Come here most weekends to get away from the city.” A sip of beer. “What do you do?”

Letterman hesitates, then thinks not to lie. “I’m a cop. Sheriff.”

Larry smiles. He likes that answer. “Really? I would have never guessed,” he says, rather sarcastically.

Letterman laughs. “What gave it away?”

They both laugh.

“You here for work? Investigating the place? Trying to find who sells the drugs.” Larry puts his hands up mockingly, “I’m a film producer, man. Honestly.”

Letterman smirks. He realizes that for the first time, he doesn’t have to beat around the bush. He grabs the man’s knee. “I won’t arrest you for drugs. Unless you want me to?”

The man looks down at his knee, then at Letterman. “You want to get out of here?”

✞

There’s a meteor shower the next night. The sky is so bright, Letterman can see the horizon. Everything around him has a light purple hue. The shadows don’t seem menacing. In the distance, coyotes howl. For the first time in his whole life, Letterman feels his a part of the cosmos of the universe. He still feels the mushrooms from the night before. The stars dance above him in a way Letterman hasn’t noticed, or admired, since he was child, taking walks at night with his father, before he passed. Letterman used to worry what his father would think of him as an adult. Yeah, he became a cop, like his dad. But his dad wasn’t picking up cadets at bars and taking them to Roy’s Motel. Or was he? Letterman never thought of it like that. Not until the shrooms. Not until he broke down and cried in front of Larry. Who put his arm around him and told him that nothing in this world matters. Look up, Larry said. We’re nothing. Letterman had heard that before. In films and New Age propaganda spread around Joshua Tree. But it never hit until last night. Why did he want to blow his brains out? For what? Out of shame? Guilt? Denial?

There’s a figure in the distance. It’s walking towards Letterman’s car. He’s off duty tonight so he gets out of his car, to let the person know he’s a cop.

“Relax, John.” It’s William Bright.

“Oh, hey,” Letterman says. He walks to meet him. “How are you tonight? I’ve never seen you outside.”

“I came to say hi to you,” William says.

“How did you know I was out here?”

“I keep cameras around.”

Letterman looks around. Where? In the cacti? On the boulders?

“Just to be safe,” William assures him.

Letterman nods.

“You’re different today,” William says.

“I’m off duty. Just came out here to see the sky.”

“That’s not it. No, it’s something in your aura.”

Letterman grimaces. Cops don’t deal with auras. They deal with body language. Tangible things.

“Yeah,” William continues. “You’re free, aren’t you?”

“I really don’t understand what you’re saying. We’re all free. This is America.”

William lets out a loud roar. So powerful Letterman feels a vibration.

“No, you weren’t free before. You were in a cage. Now you’re free.”

“Okay…”

They stand there for a few moments, looking up at the sky. Meteors —rocks the size of earth shoot about like missiles.

“I want you to come with me,” William says.

“To where?”

“The church.”

“For what?”

“To view the sky.”

“Indoors? We’re outside, the best place to view the sky.”

“No, we’re too far. We can get closer.”

William begins walking to the church. Letterman looks back at his car, then at William, who’s disappearing into the night. He’s confused. But something is telling him to go. He knows better now. He knows not to argue with forces he can’t see. So he follows William, under the cross, and inside the church.

August 11, 2015

New Short Story: Strike it Rich

“I hate this dusty fucking town,” Clara says, kicking a rock. She looks around. North: there’s nothing for miles, just lumps of dry hills. Same to her left and right. Looking South, towards Twentynine Palms Highway, she sees the Walmart where she works. It’s her day off, though, and all she wants to do is get high. “There’s nothing to do but drugs and now there’s a fucking drought? There’s a water drought and now we can’t even get our fucking drugs? This is the end. I feel it. It said it in the Bible.”

After Billy slips the letter inside the pocket of Clara’s hoodie, he stands above Clara, looking at her sleep. He’s watched her sleep for the last six years of his life. It’s what he loves most about her. Peace surrounds her, like a glowing saint. He used to be bitter of the peace she found in sleep. If only they could live there, without terrible, hypocrite parents, without drugs, without the need for money, without failure, without guilt, without regrets, without anything, just love, the only feeling that stays, then life would be bearable.

“It said they’d be a drug drought of biblical proportions?” Billy asks, squinting from the sun as he looks at Clara. They are sitting on some boulders near Billy’s house.

“Something like that, I’m sure. Why don’t you go ask your dad or something.”

“Yeah, okay,” Billy responds, chuckling. “I’ll text this guy again.”

Clara is anxious. She picks at dead skin around her fingers, then satisfies an itch on her knee, before reaching under her forearm. Her skin is the same color and texture as her surroundings: burnt, dry, and in desperate need of moisture. Over the course of two years, her blonde locks have turned scorched gold, and her teeth continue their rapid decay. She’s wearing a baggy black tee shirt with green skulls under a black hoodie and baggy black basketball shorts. All Billy’s, where’s she’s been living since she left home, a few roads down. Billy, seeing how anxious she is, grabs her by the waist, hugs her tight, then digs his hands inside her shorts.

“Ugh, Billy, get off. I don’t want to have sex, I want to get high. Did you text him?”

“I texted him, I texted him. He still hasn’t responded. It’s been days.”

“Fuck.”

“Let’s take a walk to the gas station. Maybe we’ll see someone.”

August 9, 2015

21 Interesting Words From David Foster Wallace's Vocabulary List

aerobe—organism requiring oxygen to live

afterclap—unexpected, often unpleasant sequel to a matter that had been considered closed

anaclisis—psychological dependence on others; “anaclitic”

apophasis—allusion to something by denying that it will be mentioned

bistre—yellowish-brown color

catadromous—living in freshwater but migrating to sea to breed

ecotone—transitional zone between communities containing the characteristic species of each

euphuism—ornate, allusive, overpoetic prose style

gloze—minimize or underplay… “gloze” the embarrassing part

muntin—strip of wood or metal that separates & holds various panes in a window, like a window w/ four individual panes arranged in a big rectangle, etc.

nidifugous—leaving the nest shortly after hatching

ocherous—moderate orange yellow

ordurous—dungish or shitty

patelliphobia—fear of bowls, cups, basins, and tubs

peritrichous—having a band of cilia around the mouth as certain protozoans

privity—secret, special knowledge between two or more people; (adj.) privitive

serrate—having or forming a row of sharp little teethy things

tarantism—disorder where you have uncontrollable need to dance

tardive (adj.)—having symptoms that develop slowly or appear long after inception

tenesmus—urgent but ineffectual attempt to pee or shit

valetudinarian—sickly, weak, morbidly health-conscious person

July 29, 2015

theparisreview:

“You get a tremendous boot out of what the...

“You get a tremendous boot out of what the Angels call ‘screwing it on,’ taking a big bike and just running it flat out as fast as it will go. I used to take it out at night on the Coast Highway, just drunk out of my mind, ride it for twenty and thirty miles in just short pants and a T-shirt. It’s a beautiful feeling. I recognize it as an illusion and a fantasy, but for someone who has nothing else to go back to, this is maybe one of the happiest moments of his life.”