Mat Laporte's Blog, page 13

July 11, 2016

michaelallanleonard:

L.B. Cole, November 1951

“This Is a Story About Nerds and Cops”: Predpol and Algorithmic Policing

Introduction

It is now possible to predict the future when it comes to crime, such as identifying crime trends, anticipating hotspots in the community, refining resource deployment decisions, and enduring the greatest protection for citizens in the most efficient manner.

—Colleen McCue, Data Mining and Predictive Analysis[1]

After Googling the law enforcement software start-up company PredPol (short for “predictive policing”), something strange happened—PredPol advertisements kept reappearing in my Twitter feed. PredPol wasn’t on my radar at this point—I came across the company while doing preliminary research on the use of predictive analytics in current law enforcement practices. But PredPol forced its way into my consciousness with its incessant stream of advertisements that touted PredPol was helping “build safer communities.” The first advertisement I encountered in my feed read:

“More Than a HotSpot Tool, we use no personal data to help Law Enforcement agencies to build safer communities” (@PredPol).

The advertisement tried to reassure me that the company was not monitoring my behavior, which was somewhat unsettling given that the ad likely only appeared in my feed because of my Google searches. A few days passed without me thinking much about PredPol or the creepy ads that appeared in my Twitter feed. In the meantime, I tweeted at some of my friends who are interested in policing and technology about an essay I was developing on predictive policing. In response to a tweet I posted on data and policing, a friend from New York City noted that the main thing that was unique about the statistical analysis police program CompStat was not its methodological innovations, but how it represented police ‘science’ to the public. I replied to his tweets that the use of crime statistics to legitimize the police and prisons was nothing new; since the late nineteenth-century, a data-driven approach to understanding crime has been used to perpetuate institutionalized anti-black violence. Other activist-intellectuals began to chime in the conversation and link to articles. During the conversation advertisements for PredPol began to pop up in their feeds as well as the feeds of bystanders who follow me on Twitter but did not participate in the exchange.

PredPol’s data-driven approach to policing, as well the aggressive marketing tactics deployed by the company to legitimize its methods, makes PredPol an ideal case to look at when trying to understand the algorithmic turn in policing. PredPol draws on many of the tenets of the “police science” paradigm to solve two contemporary crises: the crisis of legitimacy suffered by the police and a broader epistemological crisis that could be called the crisis of uncertainty. However, there are three major social problems that accompany the widespread use and assessment of PredPol: 1) it concedes to the inevitability of crime and creates zones of paranoia, 2) it lends itself to the generation of false positives that can be used to promote the product, and 3) it depoliticizes policing and the construction of crime.

PredPol and Algorithmic Policing

The use of predictive analytics is standard in the commercial sector. The purchases we make at the grocery store are used to determine which coupons will be printed out with our receipt, while our past purchases on Amazon are used to generate pages upon pages of product recommendations. However, the adaptation of predictive analytics in the realm of law enforcement has been more gradual, though in recent years there has been a substantial push by the tech industry to develop predictive policing technology. IBM has spent over $14 billion on developing predictive analytics software for both commerce and law enforcement sectors.[2] By late 2013, PredPol alone received $1.3 million in seed funding by Silicon Valley investors.

The ideological foundation for PredPol and other predictive policing technologies can be traced to George Kelling, a criminologist who is affiliated with the conservative Manhattan Institute. Beginning in the 1980s, he advocated the use of statistical analysis to more effectively distribute law enforcement resources. In the mid-1990s, CompStat was introduced into the New York Police Department (NYPD), which encouraged officers to make decisions about which areas to police based on statistical analysis rather than intuition. Since the 1990s, over 150 police departments nationwide have adopted policing software and equipment that allows for statistical analysis. According to SF Weekly, “Interest in predictive policing spiked nationally in 2009 as the National Institute of Justice, the research and policy branch of the Department of Justice, published a series of white papers and doled out millions in grant money to seven police departments to undertake the task.”[3]

The Los Angeles Police Department received one of these grants to undertake predictive policing research. At the same time the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was conducting research funded by the Army, Navy, and Air Force that used algorithms based on earthquake prediction to track insurgents and predict casualties in war zones overseas. This software was first used in Iraq, and later evolved into PredPol. PredPol was the brainchild of anthropology professor Jeffery Brantingham, math professor Andrea Bertozzi, and mathematics postdoctoral researcher George Mohler.

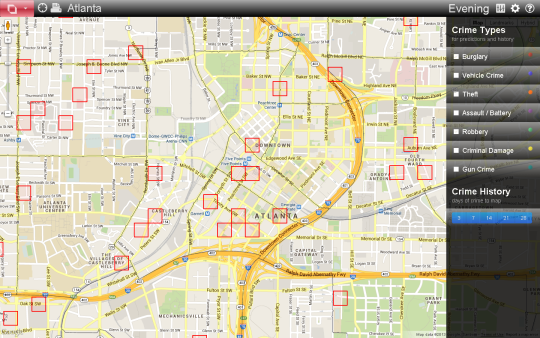

A screenshot of the Atlanta Police Department’s PredPol interface

Sean Malinowski, who oversaw the LAPD predictive policing grant, linked the efforts of the LAPD with the predictive policing methods that were being developed at UCLA. Malinowski attended the Egyptian National Police Academy in Cairo, where he studied counter-terrorism. Later, the federal-funded research project was turned into a Silicon Valley startup when Mohler, who became a professor at Santa Clara University, made connections with Ryan Coonerty, Caleb Baskin, and Zach Friend. Mohler noted that “Zach was a media mastermind – he’d worked in the press office of the 2008 Obama campaign. Once PopSci and The New York Times picked up the story, it was off to the races.”[4]

The Crisis of Legitimacy

Police brutality and violence against people of color has long been a catalyst for riots, uprisings, and civil unrest in the United States. In the post-Civil Rights era, the riot most prominently seared into the public imagination is the 1992 Los Angeles riot, which erupted on April 29, 1992 following the acquittal of the four police officers charged with the beating of Rodney King. Though the 1992 riots were the largest the United States has seen since the 1960s, numerous riots sparked by police violence against young black men have occurred in cities such as Cincinnati (2001), Oakland (2009), and most recently, Ferguson (2014).

In the past several years the has been a shift in public perception of the police. In 2014 the American Civil Liberties Union released a lengthy report on the militarization of the police based on information it collected after filing over 255 Freedom of Information Act requests in 2013. Interactions between police and social movements have also shaped the public perception of the police. In 2011 the mass arrests and violent evictions of protesters who participated in the Occupy movement generated public discussion about the militarization of the police and the use of excessive force against peaceful demonstrators. Though liberals and radicals were initially ambivalent about how these emerging social movements should relate to the police, the discourse has shifted toward a more critical stance toward the police.

In recent years, the police’s growing crisis of legitimacy is apparent in the wave of urban and suburban uprisings that have taken place in response to the murder of young black men by police officers, as well as widespread racial profiling. In 2011, at the peak of New York City’s stop-and-frisk program, 87% of the people stopped and frisked were black or Latino.[5] Massive demonstrations against stop-and-frisk took place in New York City in 2012 and in 2013 Bill de Blasio was elected mayor of New York City on a promise to overhaul stop-and-frisk. The riots and protests in Ferguson, sparked by the murder of Mike Brown, and the mass demonstrations ignited by the grand jury decisions not to indict the officers that murder Mike Brown and Eric Garner mark the pinnacle of the police’s crisis of legitimacy. Around the United States and beyond, people are chanting: “No justice, no peace, no racist police.”

According to the National Institute of Justice, “Research consistently shows that minorities are more likely than whites to view law enforcement with suspicion and distrust.” This distrust of police has been widespread among communities of color for a very long time. In the last half-decade, the majority of the major urban uprisings and riots that have occurred in the United States were ignited by police violence. Anti-police sentiment also became spectacularly visible when, in the late-1960s, the Black Panther Party formed armed patrols to “police the police” in black neighborhoods. The BPP asserted that police brutality was a cornerstone of American racism, and also popularized use of the derogatory term “pig” to refer to cops.[6]

Image of violence against “pigs,” Black Panther Party newspaper, 1969. llustration by Emory Douglas.

The legitimacy of the police has always been questioned by those who are most affected by policing, such as the poor black and brown people who are routinely stopped and frisked, harassed, surveilled and forced to live under the glare of the massive floodlights posted around NYCHA housing projects under the NYPD’s ‘Omnipresence’ program. However, in recent years this discontent has been generalized as a result of the street protests and riots that have ignited in response to police violence.

In 2011, Harvard Kennedy School and the National Institute of Justice published a paper titled, “Police Science: Toward a New Paradigm,” the ideas of which were developed at the Executive Session on Policing and Public Safety hosted at Harvard University. The paper calls for a “radical reformation of the role of science in policing” that prioritized evidence-based policies and emphasized the need for closer collaboration between universities and police departments.[7] In the opening paragraph, authors David Weisburd and Peter Neyroud assert that “the advancement of science in policing is essential if police are to retain public support and legitimacy.”[8]

This “new paradigm” is not merely a reworking of the models and practices used by law enforcement, but a revision of the police’s public image through the deployment of science’s claims to objectivity. As Zach Friend, the man behind PredPol’s media strategy, noted in an interview, “it kind of sounds like fiction, but it’s more like science fact.”[9] By appealing to “fact” and recasting policing as a neutral science, algorithmic policing attempts to solve the police’s crisis of legitimacy.

The Crisis of Uncertainty

Whereas repression has, within cybernetic capitalism, the role of warding off events, prediction is its corollary, insofar as it aims to eliminate all uncertainty connected to all possible futures. That’s the gamble of statistics technologies. Whereas the technologies of the Providential State were focused on the forecasting of risks, whether probabilized or not, the technologies of cybernetic capitalism aim to multiply the domains of responsibility/authority.

—Tiqqun, The Cybernetic Hypothesis[10]

Uncertainty is at once a problem of information and an existential problem that shapes how we inhabit the world. If we concede that we exist in a world that is fundamentally inscrutable for individual humans, then we also admit to be vulnerable to any number of risks that are outside our control. The less “in control” we feel, the more we may desire order. This desire for law and order, which is heightened when we are made aware of our vulnerability to potential threats that are unknowable to us, can be strategically manipulated by companies that use algorithmic policing practices to prevent crime and terrorism at home and abroad. Catastrophes, war, and crime epidemics may further deepen our collective desire for security.

In the age of “big data,” uncertainty is presented as an information problem that can be overcome with comprehensive data collection, statistical analysis that can identify patterns and relationships, and algorithms that can determine future outcomes by analyzing past outcomes. Predictive policing promises to remove the existential terror of not knowing what is going to happen by using data to deliver accurate knowledge about where and when crime will occur. Data installs itself as a solution to the problem of uncertainty by claiming to achieve total awareness and overcome human analytical limitations. As Mark Andrejevic writes in Infoglut, “The promise of automated data processing is to unearth the patterns that are far too complex for any human analyst to detect and to run the simulations that generate emergent patterns that would otherwise defy our predictive power.”[11]

The anonymous French ultra-leftist collective Tiqqun links the rise of crisis of uncertainty to the rise of cybernetics. Tiqqun describes cybernetics, a discipline that was founded by Norbert Wiener and others in the 1940s, as an ideology of management, self-organization, rationalization, control, automation, and technical certitude. According to Tiqqun, this ideology took root following WWII. It seeks to resolve “the metaphysical problem of creating order out of disorder” and overcome crisis, instability and disequilibrium, which Tiqqun asserts is an inherent byproduct of capitalist growth.[12] However, the “metaphysical” problem of uncertainty that is created by crisis enables cybernetic ideology to take root. Drawing on Giorgio Agamben’s State of Exception, Tiqqun writes, “The state of emergency, which is proper to all crises, is what allows self-regulation to be relaunched.”[13]

Whether or not we accept Tiqqun’s account of how capitalist growth generates a metaphysical crisis that enables the installation of cybernetic governance, it is clear that PredPol appeals to our desire for certitude and knowledge about the future. UCLA anthropology professor Brantingham emphasizes, in his promotion of PredPol, that “humans are not nearly as random as we think.”[14] Drawing on evolutionary notions of human behavior, Brantingham describes criminals as modern-day urban foragers whose desires and behavioral patterns can be predicted. By reducing human actors to their innate instincts and by applying complex mathematical models to track the behavior of these urban “hunter-gathers,” Brantingham’s predictive policing model attempts to create “order” out of the seeming disorder of human behavior.

Paranoia

But what does PredPol actually do? How does it actually work? PredPol is a software program that uses proprietary algorithms (modeled after equations used to determine earthquake aftershocks) to determine where and when crimes will occur based on datasets of past crimes. In Santa Cruz, California, one of the pilot cities to first use PredPol, PredPol used 11 years of local crime data to make predictions. In police departments that use PredPol, officers are given printouts of maps of their jurisdiction, which are covered with red square boxes that indicate where the crime is supposed to occur throughout the day. Officers are supposed to periodically patrol the boxes marked on the map in the hopes of either catching criminals or deterring potential criminals from committing crimes. The box is a kind of “temporary crime zone”: a geo-spatial area generated by mathematical models that are unknown to average police officers, who are not privy to the algorithms, though they may have access to the data that is used to make the predictions.

What is the attitude or mentality of the officer who is patrolling one of the boxes? When they enter one of the boxes, do they expect to stumble upon a crime taking place? How might the expectation of finding crime influence what the officers actually find? Will people who pass through these temporary crime zones while they are being patrolled by officers automatically be perceived as suspicious? Could merely passing through one of the red boxes constitute probable cause? Some of these questions have already been asked by critics of PredPol. As Nick O'Malley notes in an article on PredPol, “Civil rights groups are taking [this] concern seriously because designating an area a crime hot spot can be used as a factor in formulating ‘reasonable suspicion’ for stopping a suspect.”[15]

When Cleveland Police officer Timothy Loehmann arrived on the scene on November 22, 2014, it took him less that 2 seconds to fatally shoot Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy who was playing with a toy gun. This raises the question—if law enforcement officers are already too trigger-happy, will the little red boxes that mark temporary crime zones reduce the reaction time of officers while they’re in the designated boxes? How does labeling a space as an area where crime will occur affect how we interact with those spaces?

Furthermore, how might citizens experience passing through one of the boxes? If I were to one day find myself in an invisible red box with an officer, I might have an extra cause for fear, or at least would be conscious of the fact that I might be perceived as suspicious. But given that I am excluded from knowledge of where and when the red boxes will emerge, I cannot know when I might find myself in one of these temporary crime zones. Using methods that are inscrutable to citizens who do not have access to law enforcement knowledge and infrastructure, PredPol is remaking and rearranging the space through which we move. That is the nature of algorithmic policing; the phenomenological experience of policing is qualitatively different from “repressive” policing, which takes place on a terrain that is visible and uses methods that can be scrutinized and contested. Predictive policing may induce a sense of being watched at all times by an eye that we cannot see.

False Positives

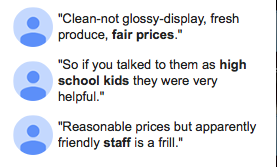

Given the difficulty of measuring the efficacy of predictive policing methods there is a risk of falsely associating “positive” law enforcement outcomes with the use of predictive policing software such as PredPol. The literature on PredPol is also fuzzy on the question of how to measure the success of PredPol. When police officers are dispatched to the 500-by-500 square boxes marked in red on city maps, are they expected to catch criminals in the act of committing crimes, or are they supposed to deter crime with their presence? The former implies that an increase in arrests in designated areas would be a benchmark of success, while the latter implies that a decrease in crime is proof of the software’s efficacy. However, both outcomes have been used to validate the success of PredPol. A news clip from PredPol’s official YouTube account narrates the story of how the Norcross Police Department (Georgia) caught two burglars in the act of breaking into a house. Similarly, an article about PredPol published on Officer.com opens with the following anecdote: “Recently a Santa Cruz, Calif. police officer noticed a suspicious subject lurking around parked cars. When the officer attempted to make contact, the subject ran. The officer gave chase; when he caught the subject he learned he was a wanted parolee. Because there was an outstanding warrant for his arrest, the subject was taken to jail.”[16]

Much of the literature of PredPol used by the company for marketing offer similarly mystical accounts of the software’s clairvoyant capacity to predict crime, which are substantiated by anecdotes about officers stumbling upon criminals in the act of committing these crimes. However, PredPol consistently claims that its efficacy can be measured by a decrease in crime. In some cases, PredPol tries to take credit for crime reduction by implying there is a causal relationship between the use of PredPol and decrease in crime rates, sometimes without explicitly making the claim. In an article linked on PredPol’s website, the author notes, “When Santa Cruz implemented the predictive policing software in 2011, the city of nearly 60,000 was on pace to hit a record number of burglaries. But by July burglaries were down 27 percent when compared with July 2010.”[17] However, crime rates fluctuate, and it is impossible to parse which factors can be credited with reducing crime. Though the article does not explicitly attribute the crime reduction to PredPol, it implicitly links the use of PredPol to the 27 percent burglary reduction by juxtaposing the two separate occurrences—the adoption of PredPol and the decrease in burglaries—so as to construct a presumed causal relation. The article goes on to use explanations made by Zach Friend (about why and how PredPol works) to validate its efficacy. Friend is described as “a crime analyst with the Santa Cruz PD;” however, Friend actually left the Santa Cruz Police Department to become one of the main lobbyists for PredPol soon after the company was founded.

By scrutinizing the PR circuits that link the UCLA researchers to the police and Silicon Valley investors to the media, one realizes that essentially all claims about the efficacy of PredPol loop back to the company itself. Though PredPol’s website advertises “scientifically proven field results,” no disinterested third party has ever substantiated the claims made by PredPol. What’s even more troubling is PredPol offered 50 percent discounts on the software to police departments that agreed to participate as a “showcase city” in PredPol’s pilot program. The program required collaboration with PredPol for three years and required police departments to provide testimonials that could be used to market the software. For instance, SF Weekly notes that:

the city of Alhambra, just northeast of Los Angeles, purchased PredPol’s software in 2012 for $27,500. The contract between Alhambra and PredPol includes numerous obligations requiring Alhambra to carry out marketing and promotion on PredPol’s behalf. Alhambra’s police and public officials must “provide testimonials, as requested by PredPol,” and “provide referrals and facilitate introductions to other agencies who can utilize the PredPol tool.[18]

In “The Difference Prevention Makes: Regulating Preventive Justice,” David Cole describe five major risks that come with the adoption of the “paradigm of prevention” in law enforcement. He notes that that, “it is not just that we cannot know the efficacy of prevention; our assessments are likely to systematically skewed.”[19] Others have raised similar concerns with PredPol. According to O’Malley, “The American Criminal Law Review has raised concerns the program could warp crime statistics, either by increasing the arrest rate in the boxes through extra policing or falsely reducing it through diffusion.”[20]

The Politics of Crime

Crime has never been a neutral category. What counts as crime, who gets labeled criminal, and which areas are policed have historically been racialized. Brantingham, the anthropologist who helped create PredPol, noted, ”The focus on time and location data — rather than the personal demographics of criminals — potentially reduces any biases officers might have with regard to suspects’ race or socioeconomic status.” Though PredPol presents itself as race-neutral, its treatment of crime as an objective force that operates according to laws that govern natural phenomena such as earthquake aftershocks, rather than a socially constructed category that only has meaning in a specific social context, ignores the a priori racialization of crime, and specifically the association of crime with blackness.

Historian Khalil Gibtan Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime and the Making of Modern America traces how “[a]t the dawn of the twentieth century, in a rapidly industrializing, urbanizing, and demographically shifting America, blackness was refashioned through crime statistics. It became a more stabilizing racial category in opposition to whiteness through racial criminalization.”[21] Muhammad describes how data was used primarily by social scientists in the North to make the conflation of blackness and criminality appear objective and empirically sound, thus justifying a number of anti-black social practices like segregation, racial violence, and penal confinement. The consolidation of this “scientific” notion of black criminality also enabled formerly criminalized immigrant populations—such as the Polish, Irish, and Italians—to be assimilated into the category of whiteness. As black Americans were pathologized by statistical discourse, the public became increasingly sympathetic to the problems of European ethnic groups, and white ethnic participation in criminal activities was attributed to structural inequalities and poverty, as opposed to personal shortcomings or innate inferiority. According to Mohammad, the 1890 census laid much of the groundwork for this ideology. He describes how statistics about higher rates of imprisonment among black Americans, particularly in northern penitentiaries, were “analyzed and interpreted as definitive proof of blacks’ true criminal nature.”[22]

My argument is not that the methods developed by PredPol themselves are racialized, but that, given that crime has historically been racialized, taking crime for granted at a neutral—or rather, natural—category around which to organize predictive policing practices is likely to reproduce racist patterns of policing. Since PredPol relies on statistics about where previous crimes have occurred, and police are more likely to police neighborhoods that are primarily populated by people of color (as well as target people of color for searches and arrests), then the data itself that PredPol relies on is systematically skewed. By presenting its methods as objective and racially neutral, PredPol veils how the data and the categories it relies on may already be systematically skewed.

Conclusion

The story of policing in the twenty-first century cannot be reduced to the stereotypical image of bellicose, meathead officers looking for opportunities to catch bad guys and to flaunt their institutional power. As PredPol Director of Business Development Donnie Fowler was quoted saying in the Silicon Valley Business Journal, twenty-first century policing could more accurately be described as “a story about nerds and cops.”[23] However, more than a story of an unlikely marriage between data-crunching professors and crime-fighting officers, the story of algorithmic policing, and PredPol in particular, is also a story of intimate collaboration between domestic law enforcement, the university, the Department of Defense, Silicon Valley, and the media. Though it is necessary to acknowledge the invisible, algorithmic (or “cybernetic”) underside of policing, it is important to recognize that algorithmic policing has not supplanted repressive policing, but is its corollary. “Soft control” has not replaced hard forms of control. Police have become more militarized now than ever as a result of the $34 billion in federal grants that have been given to domestic police departments by the Department of Homeland Security in the wake of 9/11. While repressive policing attempts to responds to events that have already occurred, algorithmic police practices attempt to maintain law and order by actively preventing crime. However, is it possible that the latter actually creates a situation that leads to the multiplication of threats rather than the achievement of safety? As predictive policing practices are taken up by local police departments across the country, perhaps we might consider the extent to which, as Tiqqun writes, “the control society is a paranoid society.”[24]

Bibliography

Andrejevic, Mark. Infoglut: How Too Much Information Is Changing the Way We Think and Know. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Bloom, Joshua. Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Bond-Graham, Darwin, and Ali Winston. "All Tomorrow’s Crimes: The Future of Policing Looks a Lot Like Good Branding.” SF Weekly, October 30, 2013, Feature sec. Accessed November 19, 2014.

Cole, David. “The Difference Prevention Makes: Regulating Preventive Justice.” Criminal Law and Philosophy (2014): 1-19.

“Dr. George Mohler: Mathematician and Crime Fighter.” DATA-SMART CITY SOLUTIONS. May 8, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/dr.-george-mohler-mathematician-and-crime-fighter-166.

Garrett, Ronnie. “Predict and Serve.” Officer.com. January 10, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.officer.com/article/10838741/predict-and-serve.

Helper, Lauren. “Coders vs. Criminals: PredPol Seeks to Scale Its Crime-prediction System.” Silicon Valley Business Journal, December 6, 2013.

Hoff, Sam. “Professor Helps Develop Predictive Policing by Using Trends to Predict, Prevent Crimes.” Daily Bruin, April 26, 2013.

Horowitz, Jake, “Making Every Encounter Count: Building Trust and Confidence in the Police,” NIJ Journal 256 (2007): 8–11.

McCue, Colleen. “Connecting the Dots: Data Mining and Predictive Analytics in Law Enforcement and Intelligence Analysis.” The Police Chief, no. 10 (2003): 115.

—-. Data Mining and Predictive Analysis. New York: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006.

Mohler, G. O. “Self-Exciting Point Process Modeling of Crime.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, no. 493 (2011): 100-08.

Morozov, Evgeny. “A critique of algorithmic regulation,” The Observer, July 20, 2014.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran,. The Condemnation of Blackness : Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Murray, Nancy. “Profiling in the Age of Total Information Awareness.” Race & Class, no. 2 (2010): 3-24.

Norcross Police Roll Out Crime Predicting Technology. Fox 5 News, 2013. Film.

O'Malley, Nick. “To Predict and to Serve: The Future of Law Enforcement.” Sidney Morning Herald, March 31, 2013, World sec.

“Scientifically Proven Field Results.” Predpol.com. 2014. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.predpol.com/results/.

Smith, Susan. “The Growth of Predictive Analytics in Law Enforcement.” Law Officer. March 25, 2014. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.lawofficer.com/article/technology-and-communications/growth-predictive-analytics-la.

Staff Reports. “Alhambra Police Unveil Crime Crystal Ball.” SGV West Valley Journal, March 1, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.sgvjournal.com/local-news/alhambra-1/1887-alhambra-police-unveil-crime-crystal-ball.html.

“Stop-and-Frisk Data,” New York Civil Liberties Union, 2014. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.nyclu.org/content/stop-and-frisk-data.

Talai, Andrew B. “Drones and Jones: The Fourth Amendment and Police Discretion in the Digital Age.” Calif. L. Rev. 102 (2014): 729-729.

Tiqqun, “The Cybernetic Hypothesis (L’Hypothèse cybernétique),” Tiqqun 2, 2001.

Vlahos, James. “The Department of Pre-Crime.” Scientific American, no. 1 (2011): 62-67.

War Comes Home At America’s Expense: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing. New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 2014.

Weisburd, David and Peter Neyroud. Police Science: Toward a New Paradigm. Cambridge, Mass: Washington, DC: Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management ; National Institute of Justice, 2011.

Welsh, Brandon. “Technological Innovations in Crime Prevention and Policing. A Review of the Research on Implementation and Impact.” Criminology & Public Policy, no. 1 (2002): 129-32.

Wolpert, Stuart. “Can Math and Science Help Solve Crimes?” US News, March 2, 2010.

[1] Colleen McCue. Data Mining and Predictive Analysis (New York: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006), xiii.

[2] Mark Andrejevic. Infoglut: How Too Much Information Is Changing the Way We Think and Know (New York: Routledge, 2013), 28.

[3] Darwin Bond-Graham and Ali Winston, “All Tomorrow’s Crimes: The Future of Policing Looks a Lot Like Good Branding,” SF Weekly, October 30, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014.

[4] "Dr. George Mohler: Mathematician and Crime Fighter,” DATA-SMART CITY SOLUTIONS, May 8, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/dr.-george-mohler-mathematician-and-crime-fighter-166.

[5] This statistic is based on the NYPD’s “Stop Question & Frisk Activity” quarterly reports, which were analyzed by the New York Civil Liberties Union. See "Stop-and-Frisk Data,” New York Civil Liberties Union, 2014. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.nyclu.org/content/stop-and-frisk-data.

[6] See Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martins comprehensive history of the Black Panther Party. Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

[7] David Weisburd and Peter Neyroud. Police Science: Toward a New Paradigm. Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management; National Institute of Justice (2011), 1.

[8] Ibid.

[9] PredPol on Current TV with Santa Cruz Crime Analyst Zach Friend. Interview with Zach Friend by Jennifer Granholm, The War Room, 2013.

[10] Tiqqun, “The Cybernetic Hypothesis (L’Hypothèse cybernétique),” Tiqqun 2 (2001), 21.

[11] Mark Andrejevic, Infoglut, 21.

[12] Tiqqun, Cybernetic, 9.

[13] Ibid, 17.

[14] Ronnie Garrett, "Predict and Serve,” Officer.com, January 10, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. http://www.officer.com/article/10838741/predict-and-serve.

[15] Nick O’Malley. "To Predict and to Serve: The Future of Law Enforcement.” Sidney Morning Herald, March 31, 2013.

[16] Garrett, “Predict.”

[17] Ibid.

[18] Darwin Bond-Graham and Ali Winston, ”All Tomorrow’s Crimes,” SF Weekly.

[19] David Cole, “The Difference Prevention Makes: Regulating Preventive Justice,” Criminal Law and Philosophy (2014): 1-19.

[20] O’Malley, Predict.

[21] Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 5.

[22] Ibid, 37.

[23] Lauren Helper, "Coders vs. Criminals: PredPol Seeks to Scale Its Crime-prediction System,” Silicon Valley Business Journal, December 6, 2013.

[24] Tiqqun, Cybernetic Hypothesis, 22.

whodatvillain:

prosthetic knowledge by

Rawtekk

July 9, 2016

July 8, 2016

morrisltibbs:

Party Girl (1995)

July 7, 2016

cinemasource:

Solaris (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky)

July 6, 2016

Mat Laporte's Blog

- Mat Laporte's profile

- 21 followers