Kim Rendfeld's Blog, page 3

December 18, 2019

Hail Mary Over the Centuries

It’s only 11 lines, but the Hail Mary, or Ave Maria, took almost a millennium to develop into the form we know today.

Hail Mary,

Full of Grace,

The Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women,

and blessed is the fruit

of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary,

Mother of God,

pray for us sinners now,

and at the hour of death.

Amen.

(From EWTN)

From Christianity’s earliest days, the Virgin Mary was an advocate for the faithful, an intercessor who would plead their case to God. Devotional images of her go back to the second century, and more Christians started to name their daughters Mary toward the end of the fourth century.

A novelist studying early medieval times can easily see her importance. Charlemagne dedicated a newly built basilica at Aachen to her. On a smaller scale, a scribe wrote, “The book was given to God and His Mother by Dido [of Laon]. Anyone who harms it will incur God’s wrath and offend His Mother.”

No surprise, then, that Christians wanted a prayer just for her. When I first wrote The Cross and the Dragon, I assumed the Ave Maria has always had its current form. I just needed the Latin translation for my characters.

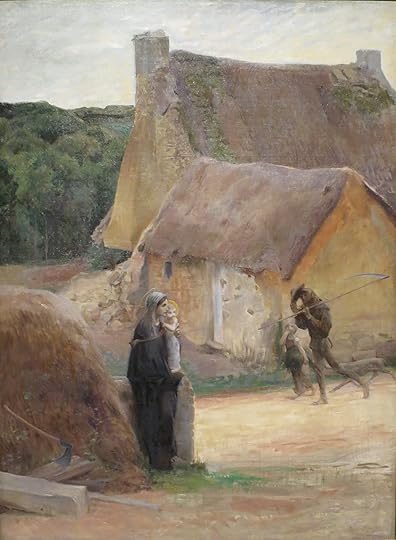

Hail, Mary by Luc-Olivier Merson, circa 1885, High Museum of Art (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Hail, Mary by Luc-Olivier Merson, circa 1885, High Museum of Art (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)Imagine my surprise when my editor informed me that Ave Maria was a lot shorter in the eighth century. “Hail, Mary, full of grace,” or words to that effect go back to the sixth century, so I could have my characters praying “Ave Maria, gratia plena.”

But it apparently took a few more centuries for the prayer to get longer. Two Anglo-Saxon manuscripts from around 1030 include “benedicta tu in mulieribus et benedictus fructus ventris tui” (“blessed are you among women and blessed is the fruit of your womb”). In the 12th century, churchmen accept the greeting to Mary as a form of devotion, as familiar as the Apostle’s Creed and the Lord’s Prayer.

And so the salutation persisted, accompanied by a gesture of homage such as genuflecting, kneeling, or bowing the head. Some saints said the Ave Maria 50 to 150 times a day.

Madonna and Child with Angels, 1425, Fra Angelico (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Madonna and Child with Angels, 1425, Fra Angelico (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)Christians had probably always greeted Mary with a request in mind such as healing a loved one’s illness, a safe return from battle, a bountiful harvest, or resisting temptation. The closing words of today’s prayer—“pray for us sinners now and at the hour of death”—originated in the 14th century and had variations throughout languages. It became part of the Roman Breviary in 1568.

What we end up with is a prayer that both venerates the Blessed Mother and asks her to use her special relationship with God on behalf of a faithful follower.

Originally published August 11, 2015, on English Historical Fiction Authors.

Sources

“Hail Mary” by Herbert Thurston, The Catholic Encyclopedia

“The Blessed Virgin Mary” by Anthony Maas, The Catholic Encyclopedia

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne by Pierre Riché

Einhard’s The Life of Charlemagne translated by Evelyn Scherabon Firchow and Edwin H. Zeydel

November 20, 2019

Rosary Beads: Steeped in Devotion and Legend

The image of a Catholic kneeling in prayer, rosary in hand

seems timeless. Having a Dark Ages character rub the beads while murmuring a

prayer wouldn’t be an anachronism, would it?

Yes and no. Christians, and people of other faiths such as

Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims, have used beads to keep track of the prayers

they were repeating. In the fourth century, Egyptian Abbot Paul used 300 pebbles

that he would drop. (Would picking up all those little stones count as penance,

too?)

By the seventh century, at least some of the faithful used strings

of beads. In early medieval times, one way for Christians to do penance and

avoid time in Purgatory was to repeat the Pater Noster 20, 50, or more times.

Most of the faithful were illiterate, so memorizing a chapter from the Bible—in

Latin—was out of the question. But they could repeat a short prayer they heard

all their lives in something that passed for Latin.

Photo by Ricce (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Photo by Ricce (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)The material for the beads depended on the owner’s wealth,

and they could be wood, bone, glass, coral, amber, or pearls. (Prayer beads made

from rose petals are documented in the 20th century.) The faithful in the Dark

Ages would not have called the beads a rosary. That would come later.

According to Catholic tradition, the Virgin Mary revealed the

prayers of the Rosary to Saint Dominic in the 13th century while he was

fighting the heresy of the Albigenses, who believed the flesh was so evil that

suicide by starvation was a good thing. However, Merriam-Webster says the first

known use of “rosary” in English was 1547.

We have several explanations for how the name of the Rosary

came about.

I like a legend of a lay brother so devoted to Mary he would

say 50 Ave Marias a day. One day while traveling through the forest, he stopped

to pray. He drew the attention of robbers, but the thieves also saw a beautiful

maiden who would take a rose from the monk’s mouth after each prayer and weave

the flowers into a crown. When the monk finished, the maiden donned the crown

and ascended to heaven.

Amazed, the robbers asked the monk who the maiden was. “What

maiden?” was the reply. Then, they all realized she had been the Virgin Mary,

and the robbers repented.

1549 painting by Barthel Bruyn the Elder (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

1549 painting by Barthel Bruyn the Elder (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)Another possibility: The rose, the queen of flowers, is a

symbol of Mary, the queen of Heaven, and the prayers are a symbolic rose garden

(rosarium in medieval

Latin).

So, my earlier question boils down to word choice. Christian

characters of any era can use prayer beads, but time period and geography

dictate whether that string of beads is called a rosary.

Sources

“Use of Beads at Prayers” by John Volz, The Catholic Encyclopedia

“The Rosary” by Herbert Thurston and Andrew Shipman, The Catholic Encyclopedia

“Albigenses” by Nicholas Weber, The Catholic Encyclopedia

“St. Dominic” by John Bonaventure O’Connor, The Catholic Encyclopedia

“Historical Rosary and Paternoster Beads” Paternoster-Row

October 23, 2019

Dark Ages Tragedy: The Baby in the River

The day must have started out like any other in eighth

century Bischofsheim. A peasant woman was about to draw water from the river.

What she saw in the water horrified her: a drowned newborn in swaddling.

The woman screamed uncontrollably and attracted a crowd. Rudolf

of Fulda, Saint Lioba’s hagiographer, says the villager was “burning with

womanly rage.” When she was able to speak, she said one of those Saxon

nuns from Britain had borne and murdered the child and then contaminated the

water with the corpse. The nuns led by Lioba protested their innocence and held

prayers and processions for God to exonerate them.

A vision like flames appeared around a crippled girl, who publicly

confessed. She was a beggar and had received food and clothing from the sisters,

but she had been absent for a while, claiming illness. Rudolf said the nuns

wept with joy at the revelation, but perhaps it was relief that everyone knew

they were indeed guiltless. I would like to think that at least some of the

nuns were shocked that someone they had helped not only ended her baby’s life

but, with the lack of baptism, also condemned the infant’s soul.

A Parisian Beggar Girl by John Singer Sargent (1880, public domain via WikiArt)

A Parisian Beggar Girl by John Singer Sargent (1880, public domain via WikiArt)This was not the only time or place parents killed their infants

during the Middle Ages, and that practice contributes to the perception that

medieval parents were not emotionally attached to their newborns. The reaction

of the woman in the village shows otherwise. She was as appalled as we would

be.

Rudolf sees this incident as the Devil using the girl to try

destroy Lioba and her abbey and the young mother’s confession as a miracle that

furthered Lioba’s cause. She and the women who braved the Channel crossing and overland

travel to today’s Tauberbischofsheim, Germany, had a lot at stake. Their abbey

was part of Saint Boniface’s mission to spread and solidify Christianity on the

Continent. If the very people the nuns were trying to help believed the women

capable of such evil, the laity might turn away from the religion, and many

souls would be lost.

The sisters’ greatest obstacle was that they were

foreigners. Lioba was born in the Saxon kingdom of Wessex and grew up in the

abbey of Wimbourne. She and the other nuns would have stood out, even if they

didn’t wear habits. Their accents and manner of speaking would be different,

and many were literate when the vast majority of the population could not read.

Whether or not the vision happened as Rudolf described, I

have a sickening feeling the murder of the baby is true.

Young Beggar by Gustave Dore (public domain via WikiArt)

Young Beggar by Gustave Dore (public domain via WikiArt) The unnamed “poor little crippled girl” was an

outcast. A medieval audience would have thought her disability was a curse from

God, perhaps a punishment for her parents’ sin, like conceiving a child on a

Sunday. She was probably a teenager, old enough to marry by medieval standards,

but her disability, poverty, and lack of family and connections made her

undesirable as a wife.

Medieval folk also would have believed the nuns did all they

could for the girl, who sat near the convent’s gate and begged for alms. Her

food came daily from Lioba’s table. The nuns provided garments and other

necessities as an act of charity.

Rudolf says only that the girl succumbed to the Devil’s

suggestions and committed fornication, but I have a feeling there is more. We

know nothing about the baby’s father. Perhaps, a man paid the girl and used her

so that she could have some means to support herself in case the nuns no longer

wished to provide for her. Or did someone get her drunk and take advantage? Maybe,

a man told her she was pretty or was simply nice to her—a powerful thing to

someone told she’s undesirable her whole life. Did she hope the man might marry

her, especially if she was fertile?

When she realized she was with child, did the girl turn to

the man who impregnated her? If he agreed to acknowledge the infant as his and

support the child but not marry her, a medieval audience would think he was

doing the right thing, and if he had a wife, she was supposed to put up with it.

But what if he refused to take any responsibility? How was a girl with no home,

relying on charity for food and clothes, going to support a baby?

How I wish this girl would have left the newborn on the

church steps and allowed her child to be taken to a monastery for the Church to

raise. But she must have been alone when she gave birth, without even a midwife

on hand. If she suffered from extreme post-partum depression, she might have

thought the baby was better off dead.

The Little Beggar by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1880, public domain via WikiArt)

The Little Beggar by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1880, public domain via WikiArt) Perhaps, she confessed to the murder because she did not

want to see the people who had shown her the most compassion to be punished.

Yet the girl’s end is as sad as her child’s. Rudolf wrote: “But the

wretched woman did not deserve to escape scot-free and for the rest of her life

she remained in the power of the devil.”

It’s uncertain what Rudolf means. Church legislators would

forgive a mother who “kills her child by magical practice by drink or any

art,” but they required penance such as a pilgrimage when travel was

dangerous and unpleasant, fasting, alms-giving, not bathing, and prayer. The

penance would last seven years if the death was to conceal adultery; three

years if the reason was poverty. I suspect the girl committed suicide, an act

beyond God’s grace in the medieval mind.

What the girl did to her baby was heinous—no other word can

describe it. Still when I think about her, I see a frightened teenager young

enough to be my daughter, without friends or family. Had one caring person been

with her at that fateful moment, could the tragedy for both mother and child

have been avoided?

Sources

Medieval Sourcebook: Rudolf of Fulda’s Life of Leoba

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne by Pierre Riché, translated by Jo Ann McNamara

Originally published July

20, 2016, on English Historical Fiction Authors.

Advertisements

October 2, 2019

Cats in the Days of King Arthur

In 5th-century Britain, cats helped humans survive winter,

but the way people regarded them depended on their religious beliefs.

Romans introduced housecats to Britain in the 1st century.

The island already had native feline species: the lynx (now extinct) and the

Scottish wildcat (now endangered). But these animals had no interest in

humans—today a Scottish wildcat remained wild, even if it’s raised in

captivity. The most significant difference between the housecat and the wildcat

is temperament. Housecats live with us, although we’re big enough to be

predators.

Unlike a lot of other animals, the early medieval housecat is

similar to today’s domestic shorthair. By contrast, horses and sheep were

smaller in the Dark Ages. Pigs had bristles and tusks. While some dog breeds

such as greyhounds and mastiffs go back to the ancients, many were quite

different from today. Some canines, like a hunting and herding dog called

alaunt, have since become extinct.

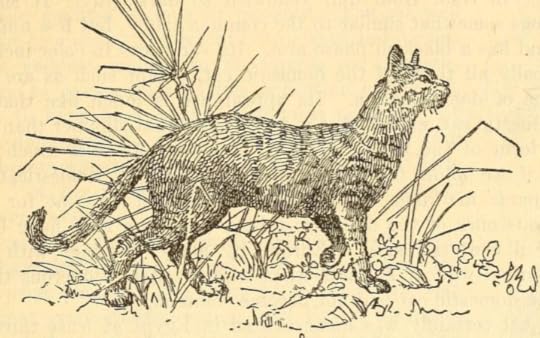

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)Cats brought by the Romans descended from the Near Eastern

wildcat, a species that hunted mice in granaries about 10,000 years ago. Today’s

Near Eastern wildcat (Felis silvestris

lybica, also called the African wildcat) looks like a large housecat with

longer legs and a more upright posture when sitting or walking. In ancient

times, the friendlier felines domesticated themselves by hanging out with the

humans who fed them table scraps. Just like a cat who decided to live with me

and my husband in the 1990s. After my husband fed her, she left a dead mouse on

the doormat. A thank-you gift, apparently.

We named the cat Ellie, and she went on to become a pampered

pet, still killing rodents on occasion. Had she lived in Arthurian Britain she

would have had a job to do—just like every human and every other animal. The

only pets, as we understand them, were toy-breed dogs for the wealthy who

wanted to show off that they could have an animal that didn’t need to do

anything. I suppose those dogs had a job, too—status symbol.

Housecats, along with ferrets and weasels, had the essential

job of killing rodents that would otherwise eat the stored grain humans needed

to get through winter. Perhaps, it is not too far a stretch for the Egyptians

to see them as divine.

By Edward Howe Forbush (1858-1929) (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

By Edward Howe Forbush (1858-1929) (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)When the Romans occupied Britain, housecats and other rodent

killers played an important role in the international economy, too. Surplus

grain from Britain was exported to the rest of the empire. A lot of people

depended on cats’ hunting skills.

Cats had a spiritual role as well. With their reproductive

abilities—a female cat can have two to three litters a year, with up to eight

kittens—they were symbols of fertility, an important thing in an age when

aristocrats needed heirs and people didn’t know how many children would live to

adulthood.

By Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany (CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

By Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany (CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons)Romans might have smuggled housecats from Egypt, where they

were believed to be too sacred for export, and some Egyptian beliefs about the

cat-headed Egyptian goddess Bastet might have seeped into Greco-Roman mythology.

Bastet, goddess of fertility and motherhood and protector of the home, became

associated with the Greek Artemis and by extension the Roman Diana. A dream about a cat was a good omen and a sign

of a good harvest.

Roman amulets to ward off evil have images of cats. Feline images

appear on a sistrum, a bronze musical instrument a handle and a rounded open

frame with bronze rods that rattled. Common in Egypt, the sistrum, associated

with fertility, also was used throughout the Roman Empire and even as far as

London.

The Celts, particularly the Irish and Scots, had their own

belief about cats. It’s possible the Kellas cat, a black hybrid of the Scottish

wildcat and housecat, had something to do with it. In the Highlands, the large

black Cat Sidhe or Cat Sith could steal the soul of the dead before the gods

claimed it, and the folk had several rituals to distract the creature until the

body was laid to rest. At Samhain, they left a saucer of milk for the Cat

Sidhe, who would bless the house. Those who neglected to leave the treat would

be cursed.

Photo of Kellas cat by Sagaciousphil (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Photo of Kellas cat by Sagaciousphil (CC BY-SA 4.0)Christian clergy saw them as companions—purring sphinxes. Greek

monks who came to Europe brought cats with them to share their cells. One of

the most delightful poems about a churchman’s relationship with his pet is the

9th century “Pangur Ban.” The Irish monk compares his hunt for knowledge to his

white cat’s hunt for mice and the joy each of them feels.

In 5th century Britain, religious beliefs were fluid. Pagan

and Christian beliefs coexisted, often in the same person. A Christian might

wear an amulet with a cat right beside their cross. They might interpret a

dream of a cat as a good omen right before they attend sunrise Mass.

Regardless of religious beliefs, people would have

appreciated how the felines preserved the food supply. That furry creature who

killed and ate mice in the granary was still essential.

Photo of wildcats by SuperJew (CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Photo of wildcats by SuperJew (CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)Sources

“Greek and Roman Household Pets” by Francis D. Lazenby

“Cats were so nice, they conquered the world twice” by Nsikan Akpan, PBS News Hour

“The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat” by Donald W. Engels, Classical Cats

“A cat that can never be tamed” by Bec Crew, Scientific American

The Cat Sidhe by Deborah MacGillivray

“House Cat Origin Traced to Middle Eastern Wildcat Ancestor” by Brian Handwerk, National Geographic News

Originally published Nov. 20, 2017, in English Historical Fiction Authors.

Advertisements

September 12, 2019

Writing about Saints—the Holy and the Human

Today, it is my pleasure to welcome my friend Tinney Sue Heath, author of Lady of the Seven Suns. This is a fabulous story about Francesco (St. Francis) and Giacoma, a Roman noblewoman who was one of his most devoted supporters (read my review on Goodreads). Here, Tinney discusses how she chose to portray Francesco as both a holy man and a real human being.—Kim

By Tinney Sue Heath

[image error]

I still can’t quite believe I wrote a book with Saint

Francis of Assisi as a major character.

It’s downright frightening to write about saints, especially

when it’s fiction, and historical fiction rather than religious fiction. Saint

Francis, or “Brother Francesco” in my book, is beloved by so many people of all

faiths and no faith, all across the world, and each one of them has a unique

idea of what he must have been like, and what he taught and believed.

Some see the happy little friar covered with twittering

birds and surrounded by Disney-like animals. Some see the radical revolutionary

who challenged the wealth and complacency of the church by his example. And

some see the man who suffered as he tried to imitate Christ, even to bearing

the stigmata on his own body.

[image error]

My main character, Giacoma, is a historical woman who seems

an unlikely friend, follower, and supporter of the saint. She was a wealthy and

powerful Roman noblewoman, and he was a barefoot friar who steadfastly refused

to own anything. Yet the two of them formed a deep and lasting bond of

friendship. Francesco even summoned “Brother Giacoma,” as he called her, to be

present at his death. It was this apparent mismatch along with their profound

mutual loyalty that intrigued me and inspired me to write the book.

[image error] By Pedro Subercaseaux Errázuris, OSB

One thing I learned is that saints tend to congregate. In Lady

of the Seven Suns you will meet not only Saint Francis (Francesco), but

also Saint Clare (Chiara), and there is a brief appearance by Saint Agnes (born

Caterina, and Chiara’s younger sister). In addition to these religious

luminaries, another character, Brother Egidio, was beatified.

[image error] Saints Francesco and Chiara, Saint Agnese, Blessed Egidio

Giacoma herself may have been beatified, or canonized. I’ve

found claims for both possibilities, though some say no official ceremony ever

took place. I cannot locate evidence for either one, but Franciscan communities

celebrate her feast day on February 8.

So this writer found herself in exalted company, trying to

write about these deeply religious people from a historical and secular point

of view. But even saints have a human side and a worldly history, and sainthood

is not conferred upon them until after they have lived out that history. So I

took a deep breath and dug in, trying to understand the world they lived in and

the loyalties, beliefs, and experiences that helped shaped them into the

extraordinary people they were.

The reader’s first glimpse of Francesco in Lady shows

him before his religious awakening, a confused young man trying to decide what

to do with his life. This view of him is documented in the early biographies

and hagiographies—a rich source of stories, like the one about the brothers

presenting Giacoma with a lamb. While I appreciated the symbolism, being the

secular novelist that I am I couldn’t resist imagining what it would be like to

share your Roman palazzo with a sheep, so I played with that idea. Many other

scenes and incidents in Lady originated in those early writings.

[image error]By José Benlliure y Gil

I came away from my writing experience with a new appreciation for what Francesco faced as he blazed his own trail and brought something genuinely original into his medieval world, and what Giacoma faced as she went against all the expectations for someone of her sex and her social caste. I don’t claim to be in any position to interpret the religious beliefs of these remarkable people, but I hope I have at least managed to show them as they might have appeared to their contemporaries.

[image error]

To learn more about Tinney, visit her website, tinneyheath.com. There, you can sign up to receive her monthly newsletter and get your free copy of Cantilena for Seven Voices: Dante’s Women Speak. You can also follow her on Facebook.

All images, with the exception of the author photo and book cover, are public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Advertisements

August 21, 2019

Saint George in Dark Ages Britain

Long before Richard the Lionhearted invoked him in the

Crusades, before he became England’s patron, Saint George was a popular figure

in medieval Christianity.

The basic story is that George was born to noble Christian

parents in Cappadocia and moved with his mother to her native Palestine after

his father died. He joined the Roman army and was named a tribune. Sometime in

his career, he rescued a princess from a dragon in the city of Selena. However,

Emperor Diocletian issued an anti-Christian edict. Refusing to renounce his

faith, George resigned his commission and complained to the emperor. For his

troubles, he was imprisoned, tortured, and beheaded around 303.

Regardless of whether the events are historically

accurate, Saint George’s legend captured medieval Christians’ imagination. The

saint’s tomb is in Lydda (later Diospolis then Lod in Israel), and after

Constantine issued an edict of tolerance in 314, churches were dedicated to

George in the region. Perhaps, pilgrims who traveled to the Holy Land brought

the saint’s legend back with them to Europe and the British Isles.

If you’re familiar with the hero’s epic of Beowulf, it’s easy to see why Saint

George caught the interest of Christians from warlike Germanic cultures such as

the Saxons and the Franks. Like Beowulf, Saint George is a tough guy who killed

a monster. The greatest different is that George makes the ultimate sacrifice

for God, while Beowulf dies in a fight for the sake of his people.

Vitale da Bologna’s Saint George’s Battle with the Dragon (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

Vitale da Bologna’s Saint George’s Battle with the Dragon (public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)On the Continent, the Franks knew about Saint George by

the sixth century. After King Clovis was

baptized in 496, he founded a monastery at Baralle in George’s honor. Clovis’s

wife, Clotilda, who wanted her husband to convert in the first place, also

honored George by building an altar and the church at Chelles.

Whether Saint George’s story had crossed the Channel at

that time is uncertain. However, around 670, Bishop Arculf, a pilgrim from

Gaul, was blown off course on his return from the Holy Land and landed on the

island monastery of Iona (also called Hy), near today’s Scotland. His host was

the Irish abbot Adamnan. As Arculf talked about the Holy Land, Adamnan wrote down

his guest’s account on wax tablets, then transcribed them to parchment and

presented Arculf’s descriptions to the king of Northumbria in 698. The

Venerable Bede also used that information in his own writing about holy places,

and his martyrology included Saint George.

Might Arculf have also told the story of Saint George during his visit? It’s possible. Saint George’s acts were translated into Anglo-Saxon, and churches were dedicated to him before the Norman Conquest. Artwork of George slaying the dragon dates back as early as the seventh century. Perhaps the image of a hero literally driving a lance through a symbol of evil (or paganism) inspired medieval Christians.

Sources

Herbert Thurston, “St. George.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6, 1909.

Godefroid Kurth, “Clovis.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4, 1908.

William Grattan-Flood, “St. Adamnan.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1, 1907.

Thomas Walsh, “Arculf.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1, 1907.

Herbert Thurston, “The Venerable Bede.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2, 1907. 14 Jun. 2014

The Edinburgh Review: Or Critical Journal, Volume 177

Originally published June 22, 2014, on English Historical Fiction Authors.

Advertisements

July 23, 2019

Character Interview: The Heroine of ‘The Cross and the Dragon’

Alda, the heroine of my first novel, The Cross and the Dragon, shares her thoughts with me on the eve of

Francia’s invasion of Hispania in 778, even though we have a language barrier.

I speak American English; Alda speaks Frankish and Roman.

[image error]

Why do you prefer

Hruodland to Ganelon?

Hruodland is a good husband. Not only is he fond of me; he

respects me as well. He doesn’t deny me anything. He likes a woman who

understands politics and the importance of good defenses. He was willing to

protect me from Ganelon, even before it was his duty.

As for Ganelon, God blessed him with good looks but not a good

brain, and his heart is as black and twisted as a spent log in the hearth. If

we had wed, I would have been at Ganelon’s mercy, and he has no mercy. The

marriage would have cost me my life or made me a murderer.

Are you still afraid of

Ganelon?

When the king ruled that my betrothal to Hruodland was valid, Ganelon

swore vengeance. My family thinks he has forgotten it. After all, he married another

woman of noble blood. He was gracious to my kin at the spring assembly in

Paderborn last year and did not give me even a hard look.

But I learned that his wife died. He said the Lord took her

after she gave birth to a girl. Something in his manner tells me it’s not the

complete truth.

What do you fear?

Losing Hruodland in Hispania. I keep thinking disaster will

strike.

Why did King Charles

decide to invade Hispania?

At the assembly in Paderborn, three emirs – Islamic noblemen –

asked for my king’s aid to overthrow the ruler of Cordoba, even though he is a

follower of Muhammad like them. They said he is seeking to expand his realm

beyond the Pyrenees and said that his subjects would rather have a godly Christian

king than someone from an ungodly and corrupt family. Winning this war would

give us access to trade routes as well as more iron for our swords and armor.

And we must consider that Church in Hispania is under Islamic rule.

My Uncle Leonhard argued that we shouldn’t get in a fight

between Islamic factions. He might be right. I had a bad feeling when I heard

them make their request, and I cannot shake it.

Why are you having a

premonition?

It goes against all reason. God has granted our king victory against

the Aquitainians, the Lombards, and the Saxons. So why would He not grant us

victory this time? Hruodland thinks it’s my humors. But he is having

nightmares, and I fear they might be an omen.

I gave him my amulet so that he would have the protection of

the dragon’s blood in its stone, and I will pray for victory every day and give

alms.

Where did the stone

come from?

Drachenfels, the mountain where Siegfried slew the dragon. It

is across the Rhine from my birthplace.

As he lay on his back in a trench, Siegfried knew he had but

one chance to slay the beast. If his blow was not true, he would be sprayed

with venom. He stabbed the monster in its underbelly as it passed over him and

then bathed in its blood. The magic made him invulnerable. Almost. Except for

where a leaf fell on his shoulder.

The mountain’s rocks hold the magic of the dragon’s blood, and

I can feel it in my amulet.

[image error]This circa 1870 painting by Arnold Forstmann (1842–after 1914) shows Nonnenwerth, along with Rolandsbogen and Drachenfels. (Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.)

Originally published June

1, 2013, on Laurie’s Paranormal Thoughts and Reviews.

Advertisements

June 19, 2019

Queen Eadburh: Maligned but Not Murderous

A woman who was once a murderous queen of

the West Saxons winds up begging in the streets of Lombardy. Lovely poetic

justice, if only it were true.

Eadburh, daughter of Mercian King Offa and

Queen Cynethryth, was a real person. She did marry a king and was widowed. And

she might have ended her days in Lombardy, but not begging and for much more

mundane reasons than those in a story written by an author currying favor with

a political enemy.

Offa (d. 796) was known for his

ruthlessness and for the dike bearing his name. Like most aristocrats, he and

his wife arranged for their children to marry for political advantage. In 789, Eadburh

wed Beorhtric, king of Wessex.

[image error]An Anglo-Saxon king and noblewoman from Costumes of All Nations (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The alliance had a mutual benefit. Beorhtric

might have come to power as an outsider taking advantage of a power vacuum when

his predecessor died. Marriage to the daughter of a powerful Mercian king

solidified his claim. In his part of the bargain, Beorhtric teamed up with Offa

to drive rival Ecgberht out of England. Beorhtric also had the dubious honor of

having Vikings land on his shore and kill his reeve.

Apparently, Eadburh did wield power and

influence. She gave away land in her own name and witnessed charters with her

husband and her brother. Even though her marriage to Beorhtric lasted several

years, they didn’t have children. Men in this age sometimes tried to repudiate

wives who didn’t produce a healthy son. Beorhtric seems to have been a

steadfast husband. Or maybe he feared upsetting Eadburh’s parents more than

dying without an heir.

After Offa died, his son, Ecgfrith,

succeeded him, and Beorhtric and Eadburh supported him. But Ecgfrith’s reign

didn’t last even a year. He died, likely not of natural causes.

Eadburh and Beorhtric’s marriage lasted

until his death in 802. He didn’t die of old age, either.

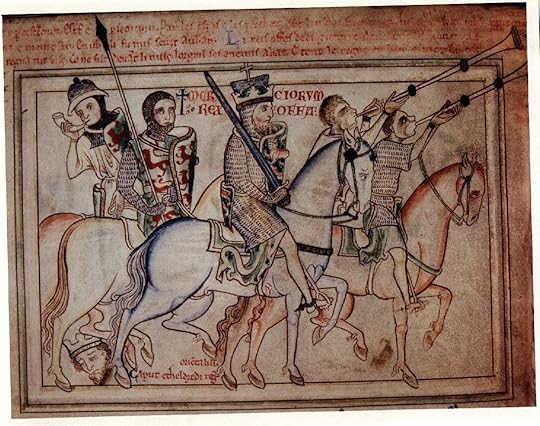

A 13th century image of Beorhtric (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

A 13th century image of Beorhtric (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)And now we get to the fiction, an account by

Asser, who wrote Life of Alfred in

893. The title character was Ecgberht’s grandson. Asser supposedly includes

Eadburh’s story to explain why the wives of the Wessex kings weren’t crowned

queen like Eadburh was and not take her seat beside him on the throne. More

likely this is an attempt to discredit the rival family.

If we are to believe Asser—and I don’t—Eadburh

was tyrannical like her father and dominated the relationship (not good in

medieval eyes). If her husband liked anyone she didn’t, she would poison the

friendship, and if that didn’t work, the poisoning took a literal turn. Poison,

the weapon of women and cowards, fits nicely into the narrative.

Eadburh planned to kill a young man she

thought was getting too close to her husband. The victim took the poison. So

did Beorhtric. Oops.

In reality, Ecgberht is the more probable

culprit. He might have invaded Wessex with his followers, and Beorhtric fell in

battle. Ecgberht subsequently seized the throne.

According to Asser, Eadburh took treasures

and fled. That much is believable. What’s next is a stretch, and that’s being

charitable.

Eadburh went to Charlemagne’s court. The

emperor, whose fifth wife had died, asked Eadburh if she wanted himself or his

son Charles. Eadburh said she preferred the younger man. Charlemagne told her

had she chosen the father, she would have gotten the son, but now she could

have neither.

This doesn’t pass the laugh test. By

medieval standards, Eadburh was not a desirable bride, especially for a royal

marriage. Her father and brother were dead, leaving her without the family

connections needed to form alliances.

[image error]Equestrian statue of Charlemagne, by Agostino Cornacchini (1725), St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican (photo by Myrabella via Wikimedia Commons, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License)

Instead, Charlemagne appointed her as an

abbess. Using another time-honored technique to discredit women, Asser says

that Eadburh was caught fornicating with one of her countrymen and expelled

from the convent on Charlemagne’s order. Somehow she made her way to Pavia with

a slave and ended her days in shame and misery as a beggar.

She might have spent the rest of her days

in Lombardy but not as a punishment or in poverty. A confraternity book written

between 825 and 850 shows an “Eadburg” as an abbess of a large Lombard convent.

If this Eadburg is the former queen of Wessex, she would be in her 50s to her

70s.

It was common for a widowed queen to

retire to a convent, and if the emperor thought her a reliable ally, he might

appoint her as the abbess. An abbess was a leader, controlling land and the

convent’s other assets, and she usually did not live an ascetic lifestyle.

The real Charlemagne very much believed in

the power of prayer, and that extended to winning wars. If he trusted Eadburh

to lead her sisters in prayer, it is possible he or his successor, Louis the

Pious, might have bestowed the abbey upon her.

This

post was originally published May 16, 2018 on English Historical Fiction

Authors.

Sources

“Eadburh” by Janet L. Nelson, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

“Beorhtric” by Heather Edwards, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Asser’s Life of King Alfred, together with the Annals of Saint Neots erroneously ascribed to Asser by John Asser, d. 909, edited by William Henry Stevenson

“A handsome, but wretched head.” by Lisa Graves, The History Witch

“Eadburh, Queen of the West Saxons” by Susan Abernethy, The Freelance History Writer

Advertisements

May 22, 2019

Charlemagne and Offa, Their Kids’ Failed Betrothals, and Trade

About 790, Frankish King Charles (Charlemagne) had a proposition for Mercian King Offa: one of Offa’s daughters marry one of Charles’s sons.

Charles likely saw this as a way to secure an alliance between a powerful kingdom in England and his vast realm—stretching from the Atlantic to east of the Rhine, from the North Sea to the Pyrenees and part of Italy. If Charles did not sire any other sons, the bridegroom, his son Charles (whom I call Karl in my books), stood to inherit all but Aquitaine and northern Italy.

Gervold, abbot of St. Wandrille, served as Charles’s envoy to work out the details. The two kings likely brought their wives into the discussions. Frankish Queen Fastrada and Mercian Queen Cynethryth were both strong-willed women. Although Karl might have also favored the marriage, but we don’t know the sentiments of the young woman involved.

In some modern eyes, princesses and other young noblewomen appear to be pawns. In medieval parents’ minds, daughters had an important role in forming the alliances and swaying their husbands to uphold her family’s interests. A husband would think his wife should convince his in-laws to side with him.

Offa of Mercia by Matthew Paris (1200-1259) (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Offa, who had seized power in 757 during a civil war after the murder of his cousin, was no exception. Although one daughter, Æthelburh, was an abbess—an influential position—another daughter, Eadburh, wed Beorhtric, king of Wessex. The marriage solidified Beorhtric’s claim to his throne, and the father- and son-in-law drove out Ecgberht, son of Kentish King Ealhmund and a rival for the West Saxon crown.

Offa had another daughter, Ælfflæd, who remained unattached in 790. Offa might have wanted her to wed a ruler in a neighboring kingdom rather than go to the continent. (She would marry Northumbrian King Æthelred I two years later.)

Offa made his own offer to Charles. He would only agree to the Frankish king’s proposition if Charles’s daughter Bertha married his son, Ecgfrith. Crowned co-ruler with his father in 787, Ecgfrith was quite the bachelor, assured of succession. Offa had, ahem, reduced the number of claimants to the throne.

But why Bertha, too young to marry at only age 11, and not her older sister, Hruodtrude, who was the marriageable age of 15? Hruodtrude had been betrothed to Byzantine Emperor Constantine, whom she never met, but that agreement fell apart a few years before.

Apparently Offa was willing to wait a couple of years as he expanded his rule into Kent. Perhaps, he thought the marriage of Charles’s second daughter to his son would remind the Kentish folk of a successful royal couple from long ago: a Merovingian princess named Bertha and Æthelberht, the most powerful Anglo-Saxon king in the late sixth century.

Charlemagne, as he appears in the 1888 The German Emperor by Max Barack (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Charles was not having it. Not at all. While he was willing for Offa’s daughter to come to Francia, learn the ways of the Frankish court, and benefit from the scholars there, he might not have wanted his own child to live in Mercia. He might have heard firsthand accounts of Offa’s ruthlessness and did not wish to subject Bertha to it.

Charles became angry, and that led to Mercia and Francia closing their ports to each other’s merchants.

This isn’t the first time a failed betrothal in Charles’s family had international consequences. According to the Revised Royal Frankish Annals, Constantine, furious at being refused Hruodtrude’s hand in marriage, ordered the Sicilians to attack Benevento, a duchy recently allied with Charles. (Exactly who dashed Constantine’s hopes is unclear. Both Charles and Empress Mother Irene take credit for the breakup.)

Yet I wonder if the cause of Charles’s ire was something in addition to a failed betrothal. Perhaps, Offa brought up another issue. Charles was sheltering Ecgberht, among other exiles, and that must have irked Offa, who still saw Ecgberht as a threat. Might Offa have demanded Charles surrender his guest as a condition for their children’s marriage? If that was the case, I can imagine Charles feeling indignant.

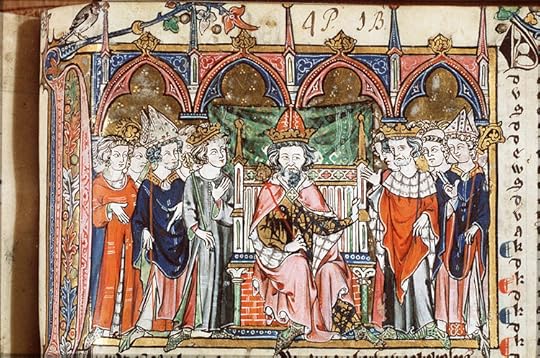

Jacob van Maerlant’s 14th century interpretation of Charlemagne at court (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

By 796, the two monarchs reconciled, and trade resumed. In an April letter from that letter, Charles calls Offa “dearest brother.”

Still, it turns out that Bertha was better off staying at home. Offa died in 796, and his son succeeded him, but Ecgfrith’s reign didn’t last even a year. He died, likely not of natural causes.

796 was a bad year for Ælfflæd, too. Her husband, Æthelred, had been a ruthless ruler, and two ealdormen took matters into their own hands and murdered him. Ælfflæd might have joined her sister Æthelburh in the cloister, a common refuge for a widowed queen. Karl himself never married. The reason remains a mystery.

Had politics not interfered with Karl and Ælfflæd’s betrothal, what kind of a couple would they have been? We’ll never know.

Sources

Charlemagne: Empire and Society, edited by Joanna Story

Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity by Rosamond McKitterick

“Carolingian Contacts,” by Janet L. Nelson, from Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, edited by Michelle P. Brown, Carol A. Farr

“Offa” by S.E. Kelly, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, c. 750–870, by Joanna Story

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

Originally published at English Historical Fiction Authors on Sept. 26, 2018.

April 25, 2019

Poetic Intellect in the Dark Ages

A poem within a poem. And the author’s only tools are stylus and wax tablet, pen and parchment.

Early medieval intellect is overshadowed by the period’s war, poverty, disease, superstition, and brutal justice. But it did exist even in an era commonly called the Dark Ages. And one wonderful example is Alcuin of York’s acrostic poem, “De Sancta Cruce” (“The Holy Cross”).

Starting with Crux decus es mundi, Iessu de sanguine sancta (“Cross, you are the world’s delight, sanctified in Jesus’s blood”), it reads line by line like a devotional piece about redemption through Christ’s sacrifice, but when read as a cross within a diamond within a square, each line has a message of salvation. The structure of the acrostic lines is symbolic. The diamond represents the world redeemed by Christ’s death and the symbol of His faith. See Futility Closet for an image of the poem and a translation.

Writers who marvel at this sophistication might wonder: How long had Alcuin worked on this poem? Did he start out writing it in this style, placing the words in a certain way, or did the structure emerge in the creative process? Did he go through several drafts on wax tablets before putting quill to expensive parchment?

Those questions remain unanswered. We do know Alcuin was educated. Born about 735 to a noble Northumbrian family, he entered the cathedral school at York as a child and was a bright pupil. Later, he directed the school for 15 years. While returning from Rome in 781, he met Charlemagne and became part of the Frankish monarch’s court.

Charlemagne receives manuscripts from Alcuin (1830 painting by Jean-Victor Schnetz, public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to being a great military leader, Charles was interested in Church reform, liked to surround himself with scholars, and had both his sons and daughters educated. The king himself could speak Latin and Greek and read, but he could not write despite an attempt to learn later in life.

Charles, his family, Alcuin, and others were among an elite few who could read. Even fewer early medieval people could write. The main reason, I suspect, is that books were expensive. They were so precious that owners invoked dire consequences if they were damaged. One scribe wrote: “The book was given to God and His Mother by Dido [of Laon]. Anyone who harms it will incur God’s wrath and offend His Mother.”

Parchment came from sheepskin, and a large book required a lot of sheep. So to have the raw materials for a book, someone needed enough land to devote to feeding sheep instead of raising crops. On top of that was the cost of labor. A normal size manuscript took a team of scribes two to three months to copy by hand, and then it was edited by the head of the shop. That doesn’t include the artist to decorate letters and paint leaves kept in reserve or the assembly and binding.

So an early medieval person’s ability to read lay in their social class rather than their intelligence.

Had books been more affordable and literacy more widespread, what other poems and writing could be with us today? What talent was never realized?

Sources

Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance, edited by Peter Godman

“Alcuin” by James Burns, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1907), retrieved from New Advent

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne by Pierre Riche

Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne by John Butt

Originally published April 8, 2015, on English Historical Fiction Authors.