Bo Bigelow's Blog, page 12

March 6, 2014

Disaster in Room B109

It is Wednesday evening, the night of our cub scouts den meeting. I am the leader for my son's den. We meet twice a month, for an hour, at 6pm in the art room of the local elementary school. On this particular night, I will bring not only Dana but Tess. Although I am the leader, the parents take turns running the meetings, so my only responsibility tonight will be to open the meeting, make a few announcements, and answer any questions parents might have. As we leave the house, I suspect that Tess might have an opinion about being at the school instead of at home. Ultimately, my suspicions will prove correct.

In the back of our car is something designed to make things easier. It is a new stroller, an umbrella-style one that is light and folds up but is also large enough to accommodate a four-year-old. I plan to put Tess in it and leave her in it for the entire meeting. I have an appointment later this week to see an orthopedist, to try to figure out what is wrong with my neck and shoulders and arms, to find out why I have numbness and tingling from my elbows down to my pinkies. I anticipate the orthopedist telling me what a great idea it is to use the stroller whenever possible, to spare my arms.

By 5pm, a full hour before the meeting starts, I have fed large dinners to both children. I have packed diapers and wipes for Tess, an array of her favorite toys, two full backup outfits, and even some more food and water, should she require it. I am ready for anything, or so I believe.

Although we leave the house with plenty of time, we are waylaid by slow drivers and icy roads, and

somehow arrive at the school at exactly 6pm. In the parking lot, I try to set up Tess's stroller but cannot seem to figure out how it works. At home it seemed so simple--just step on the crosspiece and it locks into place--but none of that is functioning. I try for several minutes to figure it out, but in the end I have no choice but to leave the stroller behind. I pick up Tess, who is feeling bitey, and run inside with her bag of toys, just behind Dana.

As I start the meeting, Tess bares her teeth even more. I can only imagine what I look like as I speak to the group of parents and scouts. It is a large den, about twenty boys, and most are in attendance. Tess alternates between sinking her teeth into my shoulder and bucking, turning herself into a human parenthesis, in order to get out of my arms and onto the floor. This requires me to perform a rather complicated dance in order to not (1) drop her or (2) get bitten. I most likely appear the way I might look if I had to stand there with a cobra up my sleeve, or with my arm on fire. My arms scream with pain, and I force myself to bring my wrists to the neutral position, the one that we're all supposed to assume while typing. I think of the stroller, sitting in my car's trunk.

At last I turn the meeting over to the parent leader, and relief is mine. Tess and I repair to the back of the room, where there is ample floor space. I break open some banana chips and water, and she is momentarily sated. After a while, we begin to play with the toys I have brought. She is quiet and happy. I take a deep breath and congratulate myself on being so ready for this meeting. I am a pro, I tell myself.

And then, something is very wrong. Dana sees it before I do. His eyes widen. He points to Tess, and I see that her chin is covered with blood. She does not seem alarmed by this. She giggles and does her best to spread the blood all over herself, me, and the floor. For the life of me, I cannot figure out how this could have happened. She has had my undivided attention. Since entering the room with her, I have not so much as checked my email. The only reason Dana has seen the blood before I have is that she is facing away from me in my lap. I locate the source of the bleeding: a tiny cut on the side of her lip. The cut is no larger than a comma on a page, but somehow she has so much blood on her face and neck, she looks like Pacino when he says the "Say hello to my little friend" line in "Scarface."

Luckily, no one else has noticed; we are at the back of the room and everyone else is focused on the parent leader. As I frantically try to wipe the blood from her face, I am dimly aware of Dana, running to the front of the room and clamoring for attention. "Everyone?" he calls out. "Um, my sister is bleeding." He points at Tess. Then, the entire room stops and stares at us--the still-bleeding Tess, the bloody rags, and me. I still do not know how she got cut, but I mumble something about how she must have caught a sharp edge on one of her toys, all of which are plush toys and thus have zero sharp edges.

Meanwhile, now Dana is also bleeding. Often he digitally causes nosebleeds, getting his finger way up there, and has chosen this moment to do so. Once the blood is flowing, he knows enough to put a wad of tissue to his nostril.

Eventually the bleeding of both children subsides. I clean up their faces. Tess becomes chatty. Her cheerful yelps increase in volume, until it becomes clear that I need to remove her from the room. As I pick her up, my arms are tired; she seems heavier than usual, as though she might have picked up an anvil, or perhaps a combination safe. Again I think of my arms and bring my wrists to neutral. "Carrying her is a bad idea," says a voice in my head, which I ignore. For some reason, I don't go get the stroller out of the car. All around me are helpful parents, who know me and know Tess and would probably sit with her for a minute while I get the stroller. But I don't think of this until afterwards, of course.

I am in the hallway just outside the meeting room, holding Tess, when it happens. I am walking, not even squatting or crouching, and my left knee suddenly explodes with agony. It is on the inside of my kneecap, a piercing, blinding pain that sends me to the floor. I weakly manage to get Tess onto my shoulder before I go down, and by some miracle I don't drop her. We lie there together for a while, me staring up at the ceiling, Tess quietly laughing. She's happy as a clam. Apparently she just wanted to have me all to herself, out in the hall. I survey the damage to my knee. While my leg is straight it's fine. But bending it brings a world of pain. I wonder if my ACL is torn. I wonder how I am going to get up.

We stay there for an undetermined amount of time. Eventually I feel okay enough to sit up. I move Tess onto my right shoulder and, keeping my left leg completely straight, I use the wall to stand up. Then I gamely limp back into the meeting, which is ending.

Despite all of this, afterwards I can only think of the meeting as a victory. There was a time when these events would have felt like a defeat. But I am getting better. It doesn't bother me that everybody saw my kid bleed while in my care, or even that I may have injured myself. When it's time to get Tess and all her gear out to the parking lot, I know enough to ask for help, although it might have been better to do so earlier. Hobbling to the car, I am able to joke with other scouts and parents. Dana, Tess and I are all still snickering when we leave.

And today the knee is feeling slightly better. I still can't bend it very well. But I can walk without too much difficulty. And hey--at least I'm already scheduled to see my orthopedist tomorrow.

In the back of our car is something designed to make things easier. It is a new stroller, an umbrella-style one that is light and folds up but is also large enough to accommodate a four-year-old. I plan to put Tess in it and leave her in it for the entire meeting. I have an appointment later this week to see an orthopedist, to try to figure out what is wrong with my neck and shoulders and arms, to find out why I have numbness and tingling from my elbows down to my pinkies. I anticipate the orthopedist telling me what a great idea it is to use the stroller whenever possible, to spare my arms.

By 5pm, a full hour before the meeting starts, I have fed large dinners to both children. I have packed diapers and wipes for Tess, an array of her favorite toys, two full backup outfits, and even some more food and water, should she require it. I am ready for anything, or so I believe.

Although we leave the house with plenty of time, we are waylaid by slow drivers and icy roads, and

somehow arrive at the school at exactly 6pm. In the parking lot, I try to set up Tess's stroller but cannot seem to figure out how it works. At home it seemed so simple--just step on the crosspiece and it locks into place--but none of that is functioning. I try for several minutes to figure it out, but in the end I have no choice but to leave the stroller behind. I pick up Tess, who is feeling bitey, and run inside with her bag of toys, just behind Dana.

As I start the meeting, Tess bares her teeth even more. I can only imagine what I look like as I speak to the group of parents and scouts. It is a large den, about twenty boys, and most are in attendance. Tess alternates between sinking her teeth into my shoulder and bucking, turning herself into a human parenthesis, in order to get out of my arms and onto the floor. This requires me to perform a rather complicated dance in order to not (1) drop her or (2) get bitten. I most likely appear the way I might look if I had to stand there with a cobra up my sleeve, or with my arm on fire. My arms scream with pain, and I force myself to bring my wrists to the neutral position, the one that we're all supposed to assume while typing. I think of the stroller, sitting in my car's trunk.

At last I turn the meeting over to the parent leader, and relief is mine. Tess and I repair to the back of the room, where there is ample floor space. I break open some banana chips and water, and she is momentarily sated. After a while, we begin to play with the toys I have brought. She is quiet and happy. I take a deep breath and congratulate myself on being so ready for this meeting. I am a pro, I tell myself.

And then, something is very wrong. Dana sees it before I do. His eyes widen. He points to Tess, and I see that her chin is covered with blood. She does not seem alarmed by this. She giggles and does her best to spread the blood all over herself, me, and the floor. For the life of me, I cannot figure out how this could have happened. She has had my undivided attention. Since entering the room with her, I have not so much as checked my email. The only reason Dana has seen the blood before I have is that she is facing away from me in my lap. I locate the source of the bleeding: a tiny cut on the side of her lip. The cut is no larger than a comma on a page, but somehow she has so much blood on her face and neck, she looks like Pacino when he says the "Say hello to my little friend" line in "Scarface."

Luckily, no one else has noticed; we are at the back of the room and everyone else is focused on the parent leader. As I frantically try to wipe the blood from her face, I am dimly aware of Dana, running to the front of the room and clamoring for attention. "Everyone?" he calls out. "Um, my sister is bleeding." He points at Tess. Then, the entire room stops and stares at us--the still-bleeding Tess, the bloody rags, and me. I still do not know how she got cut, but I mumble something about how she must have caught a sharp edge on one of her toys, all of which are plush toys and thus have zero sharp edges.

Meanwhile, now Dana is also bleeding. Often he digitally causes nosebleeds, getting his finger way up there, and has chosen this moment to do so. Once the blood is flowing, he knows enough to put a wad of tissue to his nostril.

Eventually the bleeding of both children subsides. I clean up their faces. Tess becomes chatty. Her cheerful yelps increase in volume, until it becomes clear that I need to remove her from the room. As I pick her up, my arms are tired; she seems heavier than usual, as though she might have picked up an anvil, or perhaps a combination safe. Again I think of my arms and bring my wrists to neutral. "Carrying her is a bad idea," says a voice in my head, which I ignore. For some reason, I don't go get the stroller out of the car. All around me are helpful parents, who know me and know Tess and would probably sit with her for a minute while I get the stroller. But I don't think of this until afterwards, of course.

I am in the hallway just outside the meeting room, holding Tess, when it happens. I am walking, not even squatting or crouching, and my left knee suddenly explodes with agony. It is on the inside of my kneecap, a piercing, blinding pain that sends me to the floor. I weakly manage to get Tess onto my shoulder before I go down, and by some miracle I don't drop her. We lie there together for a while, me staring up at the ceiling, Tess quietly laughing. She's happy as a clam. Apparently she just wanted to have me all to herself, out in the hall. I survey the damage to my knee. While my leg is straight it's fine. But bending it brings a world of pain. I wonder if my ACL is torn. I wonder how I am going to get up.

We stay there for an undetermined amount of time. Eventually I feel okay enough to sit up. I move Tess onto my right shoulder and, keeping my left leg completely straight, I use the wall to stand up. Then I gamely limp back into the meeting, which is ending.

Despite all of this, afterwards I can only think of the meeting as a victory. There was a time when these events would have felt like a defeat. But I am getting better. It doesn't bother me that everybody saw my kid bleed while in my care, or even that I may have injured myself. When it's time to get Tess and all her gear out to the parking lot, I know enough to ask for help, although it might have been better to do so earlier. Hobbling to the car, I am able to joke with other scouts and parents. Dana, Tess and I are all still snickering when we leave.

And today the knee is feeling slightly better. I still can't bend it very well. But I can walk without too much difficulty. And hey--at least I'm already scheduled to see my orthopedist tomorrow.

Published on March 06, 2014 08:52

March 3, 2014

Ribbons

I constantly see ribbons. Mostly on car bumpers, but sometimes on lapels. The rainbow-puzzle-piece one for autism awareness. The yellow and blue one for Down's Syndrome. Purple for cystic fibrosis.

Thing is, there isn't a ribbon for what Tess has. Mostly because we don't know what she has.

We know she has issues with processing information, both visual and auditory, but we have no diagnosis on that front. She has specific diagnoses as to various parts of her body, like her legs (hip dysplasia) and digestive system (gastroesophageal reflux disease). But as far as an overall diagnosis, one that could explain why she's so far behind other four-year-olds in terms of her language, social skills, and cognitive ability, all we have is "global developmental delay."

All that means is that Tess hasn't met her milestones. She didn't roll over when other kids did, or walk or talk when they did. She's delayed, for sure. But why? Is there a cause?

Our geneticist in Portland keeps a handwritten list of patients she hasn't been able to solve, even after round after round of genetic testing. It's a short list, maybe four or five people long. Tess is on it. The good news is that there's a ton of scary diseases that we now know Tess doesn't have. Also good news: that geneticist turns out to be uber-competitive and, when we told her we would simultaneously start seeing a geneticist at Boston Children's Hospital, she vowed that she, not Boston, would be first to crack the Tess mystery.

The two geneticists are now working together, and they're mapping Tess's genome. This means taking DNA from me, my wife, and our kids, and comparing our DNA with Tess's. She's the only one of the four of us who has these delays, so wherever our DNA differs, that's where the issue is. (I keep joking that they need to locate the gene that makes me continually leave my wallet in public places. I hope not to pass that one to either kid.)

We expect to get the mapping results next month. We've been told not to get our hopes up. If anything, we will probably only be told about a tiny genetic mutation, nothing we'll be able to use in a practical way.

There isn't an awareness week for global developmental delay or random genetic mutations. No ribbon or pin we can wear, and no bumper sticker either. This is okay. We don't need to know what Tess has. There are secret codes, after all, for we parents of globally delayed kids. For example, I am at the pool, in the water holding Tess, and a guy wades over, also holding his four-year-old. I hear him say "occupational therapy" or some other phrase, and I look at him and then we both know. The small talk falls away. We give each other a knowing nod. We briefly compare notes on the best local resources for funding and for PT, OT and speech. I ask the name of his child, and once I know it I say it aloud, deliberately pronouncing it. He does the same with Tess. I don't know why, but there is something deeply comforting about hearing this other adult--a stranger, really--say Tess's name. It is like a hundred ribbons.

Thing is, there isn't a ribbon for what Tess has. Mostly because we don't know what she has.

We know she has issues with processing information, both visual and auditory, but we have no diagnosis on that front. She has specific diagnoses as to various parts of her body, like her legs (hip dysplasia) and digestive system (gastroesophageal reflux disease). But as far as an overall diagnosis, one that could explain why she's so far behind other four-year-olds in terms of her language, social skills, and cognitive ability, all we have is "global developmental delay."

All that means is that Tess hasn't met her milestones. She didn't roll over when other kids did, or walk or talk when they did. She's delayed, for sure. But why? Is there a cause?

Our geneticist in Portland keeps a handwritten list of patients she hasn't been able to solve, even after round after round of genetic testing. It's a short list, maybe four or five people long. Tess is on it. The good news is that there's a ton of scary diseases that we now know Tess doesn't have. Also good news: that geneticist turns out to be uber-competitive and, when we told her we would simultaneously start seeing a geneticist at Boston Children's Hospital, she vowed that she, not Boston, would be first to crack the Tess mystery.

The two geneticists are now working together, and they're mapping Tess's genome. This means taking DNA from me, my wife, and our kids, and comparing our DNA with Tess's. She's the only one of the four of us who has these delays, so wherever our DNA differs, that's where the issue is. (I keep joking that they need to locate the gene that makes me continually leave my wallet in public places. I hope not to pass that one to either kid.)

We expect to get the mapping results next month. We've been told not to get our hopes up. If anything, we will probably only be told about a tiny genetic mutation, nothing we'll be able to use in a practical way.

There isn't an awareness week for global developmental delay or random genetic mutations. No ribbon or pin we can wear, and no bumper sticker either. This is okay. We don't need to know what Tess has. There are secret codes, after all, for we parents of globally delayed kids. For example, I am at the pool, in the water holding Tess, and a guy wades over, also holding his four-year-old. I hear him say "occupational therapy" or some other phrase, and I look at him and then we both know. The small talk falls away. We give each other a knowing nod. We briefly compare notes on the best local resources for funding and for PT, OT and speech. I ask the name of his child, and once I know it I say it aloud, deliberately pronouncing it. He does the same with Tess. I don't know why, but there is something deeply comforting about hearing this other adult--a stranger, really--say Tess's name. It is like a hundred ribbons.

Published on March 03, 2014 10:50

February 28, 2014

And In This Corner....

There are aspects of living with Tess that surprise us. For example, I hadn't put it together that eventually Dana would look around and see other seven-year-olds playing with their four-year-old siblings, throwing a football or riding bikes. It bothered him that Tess couldn't do these things, and why shouldn't it? He thinks about speed almost all the time; I see it in the movies marketed to him, all about race cars and speedy snails. Well, Tess is the opposite of speed. When we used to send him outside, to burn off some energy through a few laps around the house, he would return, panting, and she was a fixed point for him, sitting on the carpet, right where he left her.

And then came wrestling. The two of them were sitting on the floor together one day, when she just turned and jumped on him, basically. He's skinny for his age, and she's, um, Rubenesque by comparison. She had this crazy smile right before it happened, and then she took him down. There was no escape. He laughed, and then she laughed and tightened her choke hold. "She's making me die!" he croaked. It was awesome.

He still gets frustrated when she can't do stuff. And he still asks us when we can have another kid. (Not happening--we're done.) But now these wrestling matches are his go-to option for interacting with her. They never get tired of them. I sit and referee, mostly to prevent her from biting his ears, and I also call the fights, in a voice that's equal parts Michael Buffer and Jimmy Lennon, Jr. I call her "The Thunder Down Under" and he's "The Southern Dandy." It's during these matches that I see the most emotion in her face. When he gets close, she knows it. Sometimes she diverts her eyes, but there's no mistaking the mischief in them.

And then came wrestling. The two of them were sitting on the floor together one day, when she just turned and jumped on him, basically. He's skinny for his age, and she's, um, Rubenesque by comparison. She had this crazy smile right before it happened, and then she took him down. There was no escape. He laughed, and then she laughed and tightened her choke hold. "She's making me die!" he croaked. It was awesome.

He still gets frustrated when she can't do stuff. And he still asks us when we can have another kid. (Not happening--we're done.) But now these wrestling matches are his go-to option for interacting with her. They never get tired of them. I sit and referee, mostly to prevent her from biting his ears, and I also call the fights, in a voice that's equal parts Michael Buffer and Jimmy Lennon, Jr. I call her "The Thunder Down Under" and he's "The Southern Dandy." It's during these matches that I see the most emotion in her face. When he gets close, she knows it. Sometimes she diverts her eyes, but there's no mistaking the mischief in them.

Published on February 28, 2014 07:00

February 26, 2014

We Need to Talk

This morning, shortly after 5am, Tess was not pleased about the way things were going. She told me this. Using her teeth.

Yep, she gets bitey when she's annoyed, especially when hungry. For example, recently we were getting her ready for surgery, and she had to fast all morning, so no breakfast. Starving and furious, she eventually opened her jaws and helped herself to a chunk of a nurse's hand, and drew blood. Sure, the biting is an undesirable behavior, but it's also one of her big ways of communicating.

After all, when it comes to communication, Tess has very few words. Her lexicon looks something like this:

Mom-mom-mom = Mom, but could also mean more

Muh-muh-muh = more, but could also mean Mom

Thicka-thicka-thicka = Entertain me, please.

Geh-geh-geh = The toys you've purchased for me have become tiresome.

Don't miss the subtleties of these utterances. Thicka-thicka expresses harmless boredom, but geh-geh means business. In other words, watch yourself--you might get bitten.

She has other sounds, but these are the most common. Once in a while, she calls to her brother Dana by saying "Na-na." Occasionally she makes a sound like the laugh of Roscoe P. Coltrane, the sheriff from the old Dukes of Hazzard TV show. (The meaning of that one is unclear; I hardly think she's aspiring to catch those Duke boys.)

We are constantly exposing her to more sounds. We talk to her all the time. I even still do that singsong narration thing of my entire day with her, like I did when she was an infant: "We're going to the sto-ore. Sto-ore, sto-ore." I do this in voices both low and high, and I don't think she's ever imitated me.

But it's complicated because we don't know what she hears. There are some anomalies, to be sure. Like if our family is in a room and someone slams the door, we all jump, except for her. She might not respond at all, or might turn toward the door several seconds later. How could she not hear the door slam? Or how could it take so long for her to hear it? We know that she has issues processing visual information--does she maybe also have an auditory processing disorder?

Unfortunately, we can't test her for auditory processing. It's an emerging field, so there don't seem to be any agreed-upon criteria for such testing at her age. Even if there were, we can't exactly stick her in an audiologist's booth and tell her to raise her hand when she hears the beep. Audiology tests for her (1) require two adults besides the audiologist, to keep her sitting still, (2) involve a lot of mouthing and chewing on the headphones, and thus (3) are mostly fruitless.

Luckily, aside from her sounds, she's also got some signs. She can sign "eat," "drink," "more," and sometimes "mine." Never are these more prevalent than at mealtime. And in a major breakthrough at her school, she has just begun regularly signing "more" in connection with non-eating activities. This is huge.

We've seen other sparks of insight from her, like in making choices. Thanks to hours of work by her rockstar speech pathologist, if you hold up two toys, one of which is her favorite, and ask her to pick one, she'll choose her favorite. Even better, you can hold up pictures of the two toys, and she can point to the picture of her preferred toy. Amazing. Her ability to use the pictures is crucial, because now it's possible that she could eventually use a communication book, with multiple pictures.

We don't know yet what she can do, but I dream of that day when she opens a book and points to a picture of the toilet, to tell me she needs to go to the bathroom, or to a swingset, to say let's go swinging.

Yep, she gets bitey when she's annoyed, especially when hungry. For example, recently we were getting her ready for surgery, and she had to fast all morning, so no breakfast. Starving and furious, she eventually opened her jaws and helped herself to a chunk of a nurse's hand, and drew blood. Sure, the biting is an undesirable behavior, but it's also one of her big ways of communicating.

After all, when it comes to communication, Tess has very few words. Her lexicon looks something like this:

Mom-mom-mom = Mom, but could also mean more

Muh-muh-muh = more, but could also mean Mom

Thicka-thicka-thicka = Entertain me, please.

Geh-geh-geh = The toys you've purchased for me have become tiresome.

Don't miss the subtleties of these utterances. Thicka-thicka expresses harmless boredom, but geh-geh means business. In other words, watch yourself--you might get bitten.

She has other sounds, but these are the most common. Once in a while, she calls to her brother Dana by saying "Na-na." Occasionally she makes a sound like the laugh of Roscoe P. Coltrane, the sheriff from the old Dukes of Hazzard TV show. (The meaning of that one is unclear; I hardly think she's aspiring to catch those Duke boys.)

We are constantly exposing her to more sounds. We talk to her all the time. I even still do that singsong narration thing of my entire day with her, like I did when she was an infant: "We're going to the sto-ore. Sto-ore, sto-ore." I do this in voices both low and high, and I don't think she's ever imitated me.

But it's complicated because we don't know what she hears. There are some anomalies, to be sure. Like if our family is in a room and someone slams the door, we all jump, except for her. She might not respond at all, or might turn toward the door several seconds later. How could she not hear the door slam? Or how could it take so long for her to hear it? We know that she has issues processing visual information--does she maybe also have an auditory processing disorder?

Unfortunately, we can't test her for auditory processing. It's an emerging field, so there don't seem to be any agreed-upon criteria for such testing at her age. Even if there were, we can't exactly stick her in an audiologist's booth and tell her to raise her hand when she hears the beep. Audiology tests for her (1) require two adults besides the audiologist, to keep her sitting still, (2) involve a lot of mouthing and chewing on the headphones, and thus (3) are mostly fruitless.

Luckily, aside from her sounds, she's also got some signs. She can sign "eat," "drink," "more," and sometimes "mine." Never are these more prevalent than at mealtime. And in a major breakthrough at her school, she has just begun regularly signing "more" in connection with non-eating activities. This is huge.

We've seen other sparks of insight from her, like in making choices. Thanks to hours of work by her rockstar speech pathologist, if you hold up two toys, one of which is her favorite, and ask her to pick one, she'll choose her favorite. Even better, you can hold up pictures of the two toys, and she can point to the picture of her preferred toy. Amazing. Her ability to use the pictures is crucial, because now it's possible that she could eventually use a communication book, with multiple pictures.

We don't know yet what she can do, but I dream of that day when she opens a book and points to a picture of the toilet, to tell me she needs to go to the bathroom, or to a swingset, to say let's go swinging.

Published on February 26, 2014 09:32

February 24, 2014

Winter Travel Advisory: Stay Home

Traveling with Tess can be a breeze. She's four, but still takes a mega-nap every afternoon. She also goes down at home every night around 6:30pm, like clockwork. If we hit it just right, at night or naptime, she'll sleep through an entire car trip or even a flight. I can play cards with Dane, or read to him. But most often these days, the T-Bird doesn't sleep on trips. She realizes she's in unfamiliar places. And she makes us pay.

If there's one thing I've learned from traveling with Tess, it's this: plan for disaster, and bring extra everything.

For example, recently we took her to a medical appointment in Waltham, MA, outside Boston. We had also brought Dana, because from there we were planning to head south to Connecticut, to visit some relatives. Before the appointment, while we were getting lunch, Tess urgently needed a diaper change. They had no changing table in the bathroom, so we headed to the car. It was messy. Very messy. Without going into details, let's just say this: it required all three of us to change her. And then all four of us needed to change our entire outfits. Duuude. If we hadn't been going to Connecticut afterwards, there is no way we would have had backup clothes for anyone other than Tess. Otherwise at her doctor's appointment, it would have been Tess in her clothes, and the three of us wearing those wooden barrels with suspenders.

My wife I would love to be those people who bring their kids everywhere, showing them the world, taking them to India, Chile, or Kuala Lumpur. "The kids did great," those people unfailingly tell me upon their return. We are so not those people. I can't take Tess to Walgreens, let alone the distant corners of the globe. Before we go anywhere that's more than a couple hours from our house, we spend weeks researching our path, from our front door to our final destination. Long flights are not going to happen. We do everything possible to fly nonstop, even it means getting up at o'dark-thirty. We scout out coffee purveyors, grocery stores, changing tables, open bathrooms, places where we can sit down, moving sidewalks, wi-fi hotspots, rest stops, gate-check options, and gluten-free menus. We could write a doctoral dissertation on the varieties of strollers--their weights, incidence of wheel jamming, ease of fitting into cars, use in airports, and mechanics of checking at airport curbsides. We took the kids to Disney last year, and traveled with another family, whose kids are a few years older than Dana. As we got on the plane, the other couple had only tennis rackets and Harry Potter books. We had enough gear to sink a ship.

The most important preparation for us, though, in all travel, is about food. It's by far Tess's biggest motivator. The girl likes to eat. And no matter how much we prepare, it doesn't matter. To her, traveling is just the time between meals. And the travel gods can thwart us, even at our most prepared.

There was the time one winter when we went to Puerto Rico. We made it down to Miami and were sitting on our connecting flight. For some reason, our plane couldn't take off. We were waiting on the tarmac. Tess was a baby then, and was drinking a lot of milk. Which you can't bring through security, except in small amounts. We'd used up our supply on our first flight of the journey. In the Miami airport, it had been so early that only one place was open in our terminal. We had bought every container of milk they had left in their cooler--more than enough for the flight--but eventually while sitting there we ran out. Luckily, while we waited, the flight attendant came around with the cart to serve drinks. Imagine our shock when she wouldn't give us any milk at all. "We need it for coffee," she said. I told her we only needed a little bit, to get T to go to sleep. She refused. Tess started crying, waking up everyone in the seats around us. I eventually got up and went to the rear of the plane, to try one more time to get some milk from the flight attendant. I even offered to pay for it. No dice. By the time I got back to my seat, Tess was screaming at the top of her lungs. The next hours were a blur: the relentless sonic assault from my infant, the stares from bleary-eyed passengers, and a complete lack of any info about why we could not at least return to the airport. I remember standing up at one point and telling anyone who was listening that Tess needed milk and they wouldn't give us any. I thought about doing it over the PA, but was pretty sure that would get me deplaned into the hands of a federal marshal. But hey--at least everyone got the choice of having milk in their coffees while they waited, right? And who needs coffee? The whole plane was awake, thanks to T. Eventually, after four hours, we took off and reached our destination, Tess caterwauling all the while. That thing the pilots and crew do, where they wait by the door, and say "buh-bye" and thank you? Yeah, they didn't do that when we left.

There was the time one winter when we went to Puerto Rico. We made it down to Miami and were sitting on our connecting flight. For some reason, our plane couldn't take off. We were waiting on the tarmac. Tess was a baby then, and was drinking a lot of milk. Which you can't bring through security, except in small amounts. We'd used up our supply on our first flight of the journey. In the Miami airport, it had been so early that only one place was open in our terminal. We had bought every container of milk they had left in their cooler--more than enough for the flight--but eventually while sitting there we ran out. Luckily, while we waited, the flight attendant came around with the cart to serve drinks. Imagine our shock when she wouldn't give us any milk at all. "We need it for coffee," she said. I told her we only needed a little bit, to get T to go to sleep. She refused. Tess started crying, waking up everyone in the seats around us. I eventually got up and went to the rear of the plane, to try one more time to get some milk from the flight attendant. I even offered to pay for it. No dice. By the time I got back to my seat, Tess was screaming at the top of her lungs. The next hours were a blur: the relentless sonic assault from my infant, the stares from bleary-eyed passengers, and a complete lack of any info about why we could not at least return to the airport. I remember standing up at one point and telling anyone who was listening that Tess needed milk and they wouldn't give us any. I thought about doing it over the PA, but was pretty sure that would get me deplaned into the hands of a federal marshal. But hey--at least everyone got the choice of having milk in their coffees while they waited, right? And who needs coffee? The whole plane was awake, thanks to T. Eventually, after four hours, we took off and reached our destination, Tess caterwauling all the while. That thing the pilots and crew do, where they wait by the door, and say "buh-bye" and thank you? Yeah, they didn't do that when we left.

On each of these meltdowns, when we're miles from anywhere, when our preparation isn't enough, and the backup fails, and then the backup backup fails, I don't know what to do. Swearing helps, sometimes. But I usually find myself thinking of a friend of mine whose daughter has special needs. Rather than blaming her daughter, my friend asks herself: why am I putting her in this position? If I know she doesn't like noise, why do I take her to the noisy places?

Tess and Puerto Rico weren't a great combination, as it turned out. It was crazy hot, and she tuned out for a few days. She was listless and ate almost nothing (in spite of her voracious appetite on the plane.) Upon our return to Maine, however, what she did is burned into my memory of the trip: in the fourteen-degree temperatures of the Portland airport, she was so happy to be back in the cold that she ripped off her winter hat and started laughing. Apparently she's a cold-weather gal. Good to know.

If there's one thing I've learned from traveling with Tess, it's this: plan for disaster, and bring extra everything.

For example, recently we took her to a medical appointment in Waltham, MA, outside Boston. We had also brought Dana, because from there we were planning to head south to Connecticut, to visit some relatives. Before the appointment, while we were getting lunch, Tess urgently needed a diaper change. They had no changing table in the bathroom, so we headed to the car. It was messy. Very messy. Without going into details, let's just say this: it required all three of us to change her. And then all four of us needed to change our entire outfits. Duuude. If we hadn't been going to Connecticut afterwards, there is no way we would have had backup clothes for anyone other than Tess. Otherwise at her doctor's appointment, it would have been Tess in her clothes, and the three of us wearing those wooden barrels with suspenders.

My wife I would love to be those people who bring their kids everywhere, showing them the world, taking them to India, Chile, or Kuala Lumpur. "The kids did great," those people unfailingly tell me upon their return. We are so not those people. I can't take Tess to Walgreens, let alone the distant corners of the globe. Before we go anywhere that's more than a couple hours from our house, we spend weeks researching our path, from our front door to our final destination. Long flights are not going to happen. We do everything possible to fly nonstop, even it means getting up at o'dark-thirty. We scout out coffee purveyors, grocery stores, changing tables, open bathrooms, places where we can sit down, moving sidewalks, wi-fi hotspots, rest stops, gate-check options, and gluten-free menus. We could write a doctoral dissertation on the varieties of strollers--their weights, incidence of wheel jamming, ease of fitting into cars, use in airports, and mechanics of checking at airport curbsides. We took the kids to Disney last year, and traveled with another family, whose kids are a few years older than Dana. As we got on the plane, the other couple had only tennis rackets and Harry Potter books. We had enough gear to sink a ship.

The most important preparation for us, though, in all travel, is about food. It's by far Tess's biggest motivator. The girl likes to eat. And no matter how much we prepare, it doesn't matter. To her, traveling is just the time between meals. And the travel gods can thwart us, even at our most prepared.

There was the time one winter when we went to Puerto Rico. We made it down to Miami and were sitting on our connecting flight. For some reason, our plane couldn't take off. We were waiting on the tarmac. Tess was a baby then, and was drinking a lot of milk. Which you can't bring through security, except in small amounts. We'd used up our supply on our first flight of the journey. In the Miami airport, it had been so early that only one place was open in our terminal. We had bought every container of milk they had left in their cooler--more than enough for the flight--but eventually while sitting there we ran out. Luckily, while we waited, the flight attendant came around with the cart to serve drinks. Imagine our shock when she wouldn't give us any milk at all. "We need it for coffee," she said. I told her we only needed a little bit, to get T to go to sleep. She refused. Tess started crying, waking up everyone in the seats around us. I eventually got up and went to the rear of the plane, to try one more time to get some milk from the flight attendant. I even offered to pay for it. No dice. By the time I got back to my seat, Tess was screaming at the top of her lungs. The next hours were a blur: the relentless sonic assault from my infant, the stares from bleary-eyed passengers, and a complete lack of any info about why we could not at least return to the airport. I remember standing up at one point and telling anyone who was listening that Tess needed milk and they wouldn't give us any. I thought about doing it over the PA, but was pretty sure that would get me deplaned into the hands of a federal marshal. But hey--at least everyone got the choice of having milk in their coffees while they waited, right? And who needs coffee? The whole plane was awake, thanks to T. Eventually, after four hours, we took off and reached our destination, Tess caterwauling all the while. That thing the pilots and crew do, where they wait by the door, and say "buh-bye" and thank you? Yeah, they didn't do that when we left.

There was the time one winter when we went to Puerto Rico. We made it down to Miami and were sitting on our connecting flight. For some reason, our plane couldn't take off. We were waiting on the tarmac. Tess was a baby then, and was drinking a lot of milk. Which you can't bring through security, except in small amounts. We'd used up our supply on our first flight of the journey. In the Miami airport, it had been so early that only one place was open in our terminal. We had bought every container of milk they had left in their cooler--more than enough for the flight--but eventually while sitting there we ran out. Luckily, while we waited, the flight attendant came around with the cart to serve drinks. Imagine our shock when she wouldn't give us any milk at all. "We need it for coffee," she said. I told her we only needed a little bit, to get T to go to sleep. She refused. Tess started crying, waking up everyone in the seats around us. I eventually got up and went to the rear of the plane, to try one more time to get some milk from the flight attendant. I even offered to pay for it. No dice. By the time I got back to my seat, Tess was screaming at the top of her lungs. The next hours were a blur: the relentless sonic assault from my infant, the stares from bleary-eyed passengers, and a complete lack of any info about why we could not at least return to the airport. I remember standing up at one point and telling anyone who was listening that Tess needed milk and they wouldn't give us any. I thought about doing it over the PA, but was pretty sure that would get me deplaned into the hands of a federal marshal. But hey--at least everyone got the choice of having milk in their coffees while they waited, right? And who needs coffee? The whole plane was awake, thanks to T. Eventually, after four hours, we took off and reached our destination, Tess caterwauling all the while. That thing the pilots and crew do, where they wait by the door, and say "buh-bye" and thank you? Yeah, they didn't do that when we left.On each of these meltdowns, when we're miles from anywhere, when our preparation isn't enough, and the backup fails, and then the backup backup fails, I don't know what to do. Swearing helps, sometimes. But I usually find myself thinking of a friend of mine whose daughter has special needs. Rather than blaming her daughter, my friend asks herself: why am I putting her in this position? If I know she doesn't like noise, why do I take her to the noisy places?

Tess and Puerto Rico weren't a great combination, as it turned out. It was crazy hot, and she tuned out for a few days. She was listless and ate almost nothing (in spite of her voracious appetite on the plane.) Upon our return to Maine, however, what she did is burned into my memory of the trip: in the fourteen-degree temperatures of the Portland airport, she was so happy to be back in the cold that she ripped off her winter hat and started laughing. Apparently she's a cold-weather gal. Good to know.

Published on February 24, 2014 05:21

February 21, 2014

Alt-E

Last night, about two hours after going to bed, Tess threw up in her crib. She's a stealth puker. My wife heard a quiet cough from her room, went in there, turned on the light, and found her lying in about a quart of chunder.

We're no strangers to this; she has gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which means frequent spit-ups after meals, and sometimes as many as four changes of shirts in a day. (It also means a list of dietary restrictions longer than the U.S. tax code, but that's another story.)

Nor is the stealth part anything new. But the combination of these things--stealth, GERD, and sometimes full-on vomiting--is dangerous for Tess, because she doesn't do the usual things that we do when we throw up. She doesn't have that instinct to face downwards while it is happening. She won't call to us from her bed. Even worse, she lacks the ability to clear her airway afterwards.

We found this out a couple years ago, late one night when we checked on her in her crib. "Turn on the light," my wife said, almost immediately. Tess had thrown up. She was unresponsive, cool to the touch, and her lips were purplish-blue. She wasn't breathing right--she'd take a shallow breath and then not take one for a long time. Something was very wrong. We called 911. While waiting fifteen minutes for the EMTs, we knew her airway was blocked, but there was nothing we could do. It was agonizing.

Even after the EMTs arrived, they wouldn't use the ambulance's suction unit to clear her airway, because she was so young. My wife, who's a gastroenterologist, uses suction all the time at work. "Outta my way," she said, carrying the bluish Tess into the ambulance, and she made her way to the suction unit herself. We woke up my in-laws, who came and stayed with our son. We spent the night in the hospital with T. Doctors confirmed that some food had lodged in her airway, and her oxygen levels had gotten dangerously low. They called the incident an ALTE, which stands for Apparent Life Threatening Event. I felt that the A was unnecessary, because the word "apparent" implies that her life wasn't actually threatened. But it was. If we hadn't checked on her, we would never have known she wasn't breathing. She hadn't made a sound.

We feared that it might happen again. I wanted to get an oxygen monitor to clip on her toe, but her doctor said it wouldn't help; she'd wind up pulling it off every few seconds, causing a million false alarms, and we would learn to disregard it in the first few hours if not days. So we got a suction unit to use at home. It's the size and weight of a camera bag. A nurse aide brought it over and trained me on how to use it. It is essentially a vacuum tube with a long, pointy snoot that you can insert into her airway to suck up food and liquid. Months passed. Tess slept great and had no more ALTEs. We relaxed slightly.

This thing sucks. In a good way.

This thing sucks. In a good way.

Then, last summer, we went to Acadia National Park for an overnight. Because we are fools, we forgot the suction unit. We were staying in a rented condo with the family of our good friend Julie, who had done her medical training with my wife. All of us slept in one room. As we were going to bed, we checked on Tess, and found her just like that first time: unresponsive and not breathing. This time, we couldn't get her to take even a single breath. We whipped her out of her pack-and-play and into the hallway, calling out to Julie. For several minutes, Julie and my wife did everything they could to snap Tess out of it, alternating between slapping Tess on her back and trying to sweep her airway. We were many miles from any hospital, so calling 911 would not have done much. No matter what the two doctors did, Tess just wouldn't come around.

And then, miraculously, she did. But here's the thing: nothing came out of her mouth. Her airway wasn't blocked by any food. She just started to breathe normally again.

Was the Acadia episode a seizure? Apnea? We have been trying to solve this mystery since then. She has had a battery of tests, including a sleep study and EEG, all of which have come back normal. We suspect GERD was part of it, but if so, why didn't she spit up any food? Worst of all, if we don't know why it happened, how can we prevent it from happening again?

For now, all we can do is watch and listen. Keep checking, checking, checking. We have a Dropcam mounted above her crib. If she's sleeping on her back, we always flip her onto her side to prevent choking. We keep the pack-and-play in our room for her, and frequently put her in it. But we needed her closer after she got sick last night, so she slept in our bed. (True to all kids who do this, she made herself horizontal almost instantly, and remained the nightlong crosspiece of the letter H between my wife and me.) The suction unit was primed and ready, only a few steps away. And basically we slept with one eye open.

We're no strangers to this; she has gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which means frequent spit-ups after meals, and sometimes as many as four changes of shirts in a day. (It also means a list of dietary restrictions longer than the U.S. tax code, but that's another story.)

Nor is the stealth part anything new. But the combination of these things--stealth, GERD, and sometimes full-on vomiting--is dangerous for Tess, because she doesn't do the usual things that we do when we throw up. She doesn't have that instinct to face downwards while it is happening. She won't call to us from her bed. Even worse, she lacks the ability to clear her airway afterwards.

We found this out a couple years ago, late one night when we checked on her in her crib. "Turn on the light," my wife said, almost immediately. Tess had thrown up. She was unresponsive, cool to the touch, and her lips were purplish-blue. She wasn't breathing right--she'd take a shallow breath and then not take one for a long time. Something was very wrong. We called 911. While waiting fifteen minutes for the EMTs, we knew her airway was blocked, but there was nothing we could do. It was agonizing.

Even after the EMTs arrived, they wouldn't use the ambulance's suction unit to clear her airway, because she was so young. My wife, who's a gastroenterologist, uses suction all the time at work. "Outta my way," she said, carrying the bluish Tess into the ambulance, and she made her way to the suction unit herself. We woke up my in-laws, who came and stayed with our son. We spent the night in the hospital with T. Doctors confirmed that some food had lodged in her airway, and her oxygen levels had gotten dangerously low. They called the incident an ALTE, which stands for Apparent Life Threatening Event. I felt that the A was unnecessary, because the word "apparent" implies that her life wasn't actually threatened. But it was. If we hadn't checked on her, we would never have known she wasn't breathing. She hadn't made a sound.

We feared that it might happen again. I wanted to get an oxygen monitor to clip on her toe, but her doctor said it wouldn't help; she'd wind up pulling it off every few seconds, causing a million false alarms, and we would learn to disregard it in the first few hours if not days. So we got a suction unit to use at home. It's the size and weight of a camera bag. A nurse aide brought it over and trained me on how to use it. It is essentially a vacuum tube with a long, pointy snoot that you can insert into her airway to suck up food and liquid. Months passed. Tess slept great and had no more ALTEs. We relaxed slightly.

This thing sucks. In a good way.

This thing sucks. In a good way.Then, last summer, we went to Acadia National Park for an overnight. Because we are fools, we forgot the suction unit. We were staying in a rented condo with the family of our good friend Julie, who had done her medical training with my wife. All of us slept in one room. As we were going to bed, we checked on Tess, and found her just like that first time: unresponsive and not breathing. This time, we couldn't get her to take even a single breath. We whipped her out of her pack-and-play and into the hallway, calling out to Julie. For several minutes, Julie and my wife did everything they could to snap Tess out of it, alternating between slapping Tess on her back and trying to sweep her airway. We were many miles from any hospital, so calling 911 would not have done much. No matter what the two doctors did, Tess just wouldn't come around.

And then, miraculously, she did. But here's the thing: nothing came out of her mouth. Her airway wasn't blocked by any food. She just started to breathe normally again.

Was the Acadia episode a seizure? Apnea? We have been trying to solve this mystery since then. She has had a battery of tests, including a sleep study and EEG, all of which have come back normal. We suspect GERD was part of it, but if so, why didn't she spit up any food? Worst of all, if we don't know why it happened, how can we prevent it from happening again?

For now, all we can do is watch and listen. Keep checking, checking, checking. We have a Dropcam mounted above her crib. If she's sleeping on her back, we always flip her onto her side to prevent choking. We keep the pack-and-play in our room for her, and frequently put her in it. But we needed her closer after she got sick last night, so she slept in our bed. (True to all kids who do this, she made herself horizontal almost instantly, and remained the nightlong crosspiece of the letter H between my wife and me.) The suction unit was primed and ready, only a few steps away. And basically we slept with one eye open.

Published on February 21, 2014 06:34

February 20, 2014

What This Is

I just turned 40 this month. Though I had been writing for years, I had chosen not to write about Tess. After all, I had stories to tell! I was writing about food trucks and murderers, about jetpacks and machines that could record and play back memories. I had quit my law job to stay at home, and I had only a few things to say about that home life, just enough for some short pieces on Playground Dad. Sure, there was plenty of drama at home, but I kept it to myself.

But then, right before my birthday, I talked with another writer, a guy who's also going through some stuff, with a medically fragile kid. Even though our kids' situations are completely different, I saw in his stories some of what I felt with Tess: the dizzying unpredictability, the numbing hours spent in hospital rooms. Above all, his writing seemed to help him make sense of things.

So when I turned the big 4-0, I decided to see how it felt. Just to see what I have to say. I purposely wrote it on my personal blog, because no one reads that (I have, like, one follower); even if my writings were out there, at least they wouldn't be out there. These entries would be more for myself than anyone else. What I forgot was that I had configured that blog to automatically post on Facebook. Turns out.

Since then I've heard from friends far and wide, some of whom I haven't talked to in ten years or more. Their support has been astounding, and I am really grateful. I guess I have more to say than I realized. Stay tuned.

But then, right before my birthday, I talked with another writer, a guy who's also going through some stuff, with a medically fragile kid. Even though our kids' situations are completely different, I saw in his stories some of what I felt with Tess: the dizzying unpredictability, the numbing hours spent in hospital rooms. Above all, his writing seemed to help him make sense of things.

So when I turned the big 4-0, I decided to see how it felt. Just to see what I have to say. I purposely wrote it on my personal blog, because no one reads that (I have, like, one follower); even if my writings were out there, at least they wouldn't be out there. These entries would be more for myself than anyone else. What I forgot was that I had configured that blog to automatically post on Facebook. Turns out.

Since then I've heard from friends far and wide, some of whom I haven't talked to in ten years or more. Their support has been astounding, and I am really grateful. I guess I have more to say than I realized. Stay tuned.

Published on February 20, 2014 04:06

February 19, 2014

These Hips Are Made for Walking. Maybe.

Three Aprils ago, Tess was not quite two. We had vague ideas of her delays, but most of them had not yet crystallized. One of the things we noticed was that she was not walking, or even standing. She could crawl, but we suspected something might be amiss. Wherever we went, she had to be carried, because--god bless her--she hated her stroller. Also hated sitting in shopping carts. She was starting to get heavy.

Sure enough, her orthopedist X-rayed her and told us she had hip dysplasia. Basically, he said, her femurs weren't aligned with her acetabulum. I am the least medical person on earth, so at every appointment I need the doctor to dumb it down about four times. So for those of you like me: her leg bones didn't fit into their sockets properly.

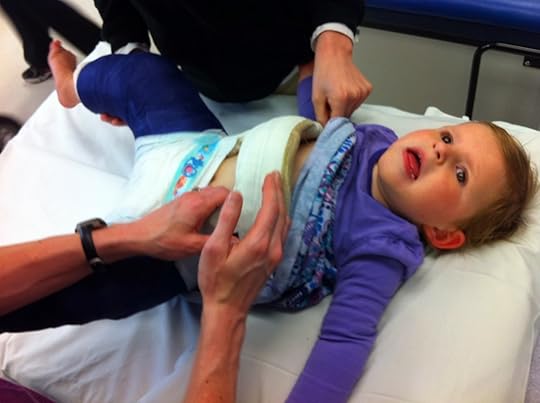

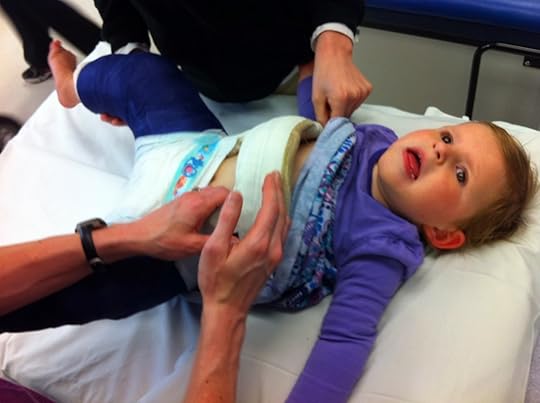

She had surgery and then went into a body cast for ten weeks. They call it a spica cast. It went from her armpits down to her ankles. It had a hole slightly smaller than her diaper. Bathing her was impossible, and changing her was an unpleasant experience for all involved. Her physical therapist got us in touch with another family of a kid with hip dysplasia who'd gone through casting. They were awesome. They gave us support and helpful tips (get a beanbag chair). During those weeks of carrying her, she was heavy with the cast, but one good thing was that she couldn't wriggle on my hip; the cast kept her in place. At least this'll fix things and she can walk soon, we figured.

Tess in her cast

Tess in her cast

A year later, at two, she still wasn't walking. Still insisted on parking her little self on my hip wherever we went. She wasn't so little anymore, though, and was getting heavier all the time. On Groundhog Day--literally--her orthopedist told us her leg bones were out of her sockets and she needed surgery and another body cast. This time, he assured us, it would stick. He would put screws and plates into her pelvis to keep everything in place.

We got through the second spica cast. If you're out there and facing hip dysplasia and a spica cast for your kid, don't worry--it ends, and you can do it. The hospital sawed the accursed thing off her at the end and we rejoiced. I recall looking at my arms as we neared the end, and noticing that one arm was substantially larger, because that is the side I carry her on. Sometimes I woke in the night with numbness in my hands. We were on the road to walking, we thought.

Even after that second cast, Tess didn't feel like walking. She started therapeutic horseback riding, and that seemed to jar something loose, because she was suddenly crawling. But we still needed to carry her.

After the second cast was removedNow she's four and a half. A few weeks ago, she had another hip surgery, this time to remove the hardware from her pelvis. The orthopedist emerged from the OR carrying a screw-top container, like you'd get at a hardware store, with the silvery plates and screws rattling around inside. Her hips are now where they should be. But she is still not walking. Pushing forty pounds.

After the second cast was removedNow she's four and a half. A few weeks ago, she had another hip surgery, this time to remove the hardware from her pelvis. The orthopedist emerged from the OR carrying a screw-top container, like you'd get at a hardware store, with the silvery plates and screws rattling around inside. Her hips are now where they should be. But she is still not walking. Pushing forty pounds.

What is the solution to this? Man, I wish I knew. We have an adaptive stroller for her, but she despises it. She's warmed slightly to the shopping cart, but otherwise she's on my hip. One of her favorite tricks is to arch her back so I will put her down, but in the grocery store that's not an option. I try to do errands while she's in school, but I still have to carry her a fair amount.

Part of the solution is to work out. A lot. My wife and I do that, both for sanity and to be able to carry Tess. (Side note: my in-laws cared for our kids recently while we took a trip, and they prepared by working out with medicine balls, to simulate lifting and carrying her.) I do yoga, go to Crossfit, see a chiropractor, and get sports massages. At home, I stretch and use a foam roller. In the car, I focus on posture and try to lengthen my neck. But the physical demands of caring for Tess are starting to take their toll. My neck, back and shoulders are a disaster. On the side where I carry her, I have something that resembles carpal tunnel syndrome. It might be something more serious. I'm not sure.

She has begun to take steps while holding our hands. We think she'll walk soon. But we were thinking that two years ago. She might never walk, for all we know.

One thing is clear: she's a strong little bird. During her most recent surgery, her doctor told us that some of her bone had grown over the hardware, so it had been necessary to chip it out of there with a bone chisel. She showed us one of the plates he'd pulled out of her. It was dented and dinged up, like it had been dragged behind a car for a few miles. "She'll be a little sore," he said. At each surgery she cries, the way anyone would, but there is also a fire in her eyes. Her eyes shine, daring you to do your worst, as if she's thinking: "Is that all you got?" Our seven-year-old son told her once, "You got a tough heart, Tess." It has become a household saying.

Sure enough, her orthopedist X-rayed her and told us she had hip dysplasia. Basically, he said, her femurs weren't aligned with her acetabulum. I am the least medical person on earth, so at every appointment I need the doctor to dumb it down about four times. So for those of you like me: her leg bones didn't fit into their sockets properly.

She had surgery and then went into a body cast for ten weeks. They call it a spica cast. It went from her armpits down to her ankles. It had a hole slightly smaller than her diaper. Bathing her was impossible, and changing her was an unpleasant experience for all involved. Her physical therapist got us in touch with another family of a kid with hip dysplasia who'd gone through casting. They were awesome. They gave us support and helpful tips (get a beanbag chair). During those weeks of carrying her, she was heavy with the cast, but one good thing was that she couldn't wriggle on my hip; the cast kept her in place. At least this'll fix things and she can walk soon, we figured.

Tess in her cast

Tess in her castA year later, at two, she still wasn't walking. Still insisted on parking her little self on my hip wherever we went. She wasn't so little anymore, though, and was getting heavier all the time. On Groundhog Day--literally--her orthopedist told us her leg bones were out of her sockets and she needed surgery and another body cast. This time, he assured us, it would stick. He would put screws and plates into her pelvis to keep everything in place.

We got through the second spica cast. If you're out there and facing hip dysplasia and a spica cast for your kid, don't worry--it ends, and you can do it. The hospital sawed the accursed thing off her at the end and we rejoiced. I recall looking at my arms as we neared the end, and noticing that one arm was substantially larger, because that is the side I carry her on. Sometimes I woke in the night with numbness in my hands. We were on the road to walking, we thought.

Even after that second cast, Tess didn't feel like walking. She started therapeutic horseback riding, and that seemed to jar something loose, because she was suddenly crawling. But we still needed to carry her.

After the second cast was removedNow she's four and a half. A few weeks ago, she had another hip surgery, this time to remove the hardware from her pelvis. The orthopedist emerged from the OR carrying a screw-top container, like you'd get at a hardware store, with the silvery plates and screws rattling around inside. Her hips are now where they should be. But she is still not walking. Pushing forty pounds.

After the second cast was removedNow she's four and a half. A few weeks ago, she had another hip surgery, this time to remove the hardware from her pelvis. The orthopedist emerged from the OR carrying a screw-top container, like you'd get at a hardware store, with the silvery plates and screws rattling around inside. Her hips are now where they should be. But she is still not walking. Pushing forty pounds.What is the solution to this? Man, I wish I knew. We have an adaptive stroller for her, but she despises it. She's warmed slightly to the shopping cart, but otherwise she's on my hip. One of her favorite tricks is to arch her back so I will put her down, but in the grocery store that's not an option. I try to do errands while she's in school, but I still have to carry her a fair amount.

Part of the solution is to work out. A lot. My wife and I do that, both for sanity and to be able to carry Tess. (Side note: my in-laws cared for our kids recently while we took a trip, and they prepared by working out with medicine balls, to simulate lifting and carrying her.) I do yoga, go to Crossfit, see a chiropractor, and get sports massages. At home, I stretch and use a foam roller. In the car, I focus on posture and try to lengthen my neck. But the physical demands of caring for Tess are starting to take their toll. My neck, back and shoulders are a disaster. On the side where I carry her, I have something that resembles carpal tunnel syndrome. It might be something more serious. I'm not sure.

She has begun to take steps while holding our hands. We think she'll walk soon. But we were thinking that two years ago. She might never walk, for all we know.

One thing is clear: she's a strong little bird. During her most recent surgery, her doctor told us that some of her bone had grown over the hardware, so it had been necessary to chip it out of there with a bone chisel. She showed us one of the plates he'd pulled out of her. It was dented and dinged up, like it had been dragged behind a car for a few miles. "She'll be a little sore," he said. At each surgery she cries, the way anyone would, but there is also a fire in her eyes. Her eyes shine, daring you to do your worst, as if she's thinking: "Is that all you got?" Our seven-year-old son told her once, "You got a tough heart, Tess." It has become a household saying.

Published on February 19, 2014 05:07

February 18, 2014

Phone Booths Aren't Just for Superman: How to Kick Butt and Get Things Done by Phone

I've gotten some great responses from last week's post about how I deal with insurance companies. Apparently I'm not the only one who's had a few issues with them.

Look, I'm not an expert. I'm just a guy who makes a lot of phone calls. My daughter has special needs and a lot of stuff goes down with her equipment, medical bills and appointments. My only expertise comes from experience. But I have found a few methods that work for me, when using the phone to get things done, no matter who I need to call. So here they are:

(1) Get a person. Whether I'm trying to phone my bank, a hospital, a billing center, or my governor, I don't mess around with automated menus. If you do, you're being only slightly more productive than you would be in, say, slamming your head in your car door.

Do whatever you need to do to get a human being on the other end of the phone, right out of the gate. Good news is, there are other people who've blazed most of these trails before, and you can get specific instructions on how to bypass menus at Dial A Human, Get Human, and Get2Human.

(2) Hold people accountable. When I ask my first question and get my first answer, I always get the name of the person. Next, there are six simple words I say to demonstrate that I am not to be messed with: "What's your extension or operator number?"

The Empire used this technique against

The Empire used this technique against Han Solo: "What's your operating number?"It's key to ask for both; if I just say, "What's your extension?" some service reps like to play semantic games and say, "We don't have extensions." Don't let it end there. After all, you aren't getting this info so you can call them directly. Instead, it's so you can identify them later on. That way, if they don't end up doing the right thing and you have to call back, you'll say, "On October 3rd I talked to Shannon, operator number 4499zgz, and she told me I'd get a refund within two business days."

Once you have their name and number, don't be surprised to hear them bend over backwards to clarify stuff they said earlier. You're literally kicking ass and taking names.

And once I have their name, I use it. I also use mine and my kid's too. Make your call about people, not transactions. Which will get you farther: "I'm calling about a delay" or "Tess will have to do without her eye medicine until next Tuesday"?

Another nifty move: repeat the person's position back to them. It could go something like this: "So let me get this straight--you never billed me for this, the first time I'm hearing it is during this call, and you're still charging me a late fee?"

(3) Take notes and use them. As I make these calls, I sometimes think that I'll remember everything that's said. I won't. Especially since I had my kids; my memory isn't what it once was. So I make detailed notes while I'm talking.

I've written before about three ways to harness the power of digital lists, but you need nothing more than an email account in order to make this happen. Just compose an email to yourself for each call, and in the subject line, put the date and who you're calling, so you can search for it later. Enter the person's name and extension or operator number. Type short notes of what you say and what they say.

If the issue's complex, sometimes I even type up a few notes before the call, to ensure that I cover everything. I put them at the top of my email to myself, as little dashes. All you need is enough to jog your memory, like this:- bill of Feb 19- never got replacement part- items were damaged

I take my time, both talking and typing. These notes will be my ammo, so if they come out as an incoherent mess they'll be useless. I'm never afraid to let the person hear me taking notes. If anything, it'll make them more aware that I'm the real deal, so they won't be as quick to dismiss me.

(4) Record the call, or go conference on 'em. If there's too much going on and you really can't take notes on it, you might want to just go ahead and start recording your calls. Lifehacker has this handy guide. Just be sure to notify the other person that you're recording them. This move can be as powerful as a conference call (which you should totally do if you're getting contradictory stories from two different companies or entities). Last week's post talked about how I use conference calls on offense when I'm getting the runaround.

So that's how I roll, phone-wise. Note that these hints are best for when you've initiated the calls, but there's a whole lot of other laws and rights that apply when someone else is calling you, like a debt collector. If you're getting hounded unfairly, contact a consumer-protection attorney and learn about your rights. None of what I've written here is legal advice.

I hope this helps you, especially if you're a special-needs parent trying to get things done for your kid. Stay tuned--in the coming weeks I'll be posting about taking it to the next level, when it's time to hang up the phone and really go to war.

Published on February 18, 2014 04:23

February 17, 2014

We Did This to Ourselves

Louis CK says he knows why we can't resist constantly whipping out our phones, even while driving. It's to avoid having to feel things like doubt and fear and disappointment. That's probably why my seven-year-old Dana is glued to my wife's phone tonight. I make him shut it off, but I can't blame him. We are in a restaurant, and everything kind of sucks. There have been many successes with taking Tess out to eat. But this isn't one of them.

We can't be certain what Tess can visually process, but she does well in familiar places. Ten minutes from our house is our go-to family restaurant, a tavern with good lighting, decent food, and a waitress who knows Tess. Even when crowded, it stays fairly quiet, which is key for Tess, who can't deal with noise. We can't go there tonight, though. It's packed because it's Valentine's Day (duh). The hostess tells us it'll be 45 minutes. Which is a dealbreaker, since the kids are already hungry.

Our backup option is a pizza place. The lighting is poor and the dining room is loud. Within seconds of putting Tess in the high chair, she begins violently bucking forward and backward as though she is part of an Olympic event rather than a meal.

In restaurants you can't leave anything within her reach or she will pick it up and try to eat it. So we have to completely clear her reach radius of napkins, silverware, menus, salt and pepper shakers, and the crayons and paper they bring for kids. She's like Homer in the all-you-can-eat seafood episode of the Simpsons ("'Tis not a [girl], 'tis a remorseless eating machine!") Unfortunately--and this is why the boy is miserable--the table is small, and now the rest of us are crammed onto one side. Our drinks come and there's nowhere to put them. We've ordered a large pizza, which requires a lengthy conference with our waitress, to discuss all aspects of restructuring our plate configuration, in order to make room for it but still have it away from Tess.

Nothing on the menu is good for her. She's dairy-free and gluten-free. Even at the tavern, she hasn't done well lately with waiting for food to arrive, so luckily we've brought an entire dinner for her, in her school lunchbox. She finishes it before our pizza comes. Once we dig into our slices, she begins yelling. The people around us start to notice.

Nothing on the menu is good for her. She's dairy-free and gluten-free. Even at the tavern, she hasn't done well lately with waiting for food to arrive, so luckily we've brought an entire dinner for her, in her school lunchbox. She finishes it before our pizza comes. Once we dig into our slices, she begins yelling. The people around us start to notice.

I tell myself how good this is that she's making her feelings known. For many months of her life she was almost catatonic, not communicating or responding to sounds. She would have sat in the high chair, numbly chewing, and we would have had no idea what she liked or didn't like. In the past year, though, she's awakened. She only has a couple of words ("more" and "Mom"), but she lets us know with other noises when she's annoyed. And now she's shouting so loudly that we need to leave. Immediately.

Our waitress is nowhere to be found. "Dane," I say, "keep cool and we'll watch some olympics when we get home." He settles, but we're on borrowed time. Alas, there is no placating Tess when she's like this. You can't discipline her, talk her down, or promise her something in exchange for good behavior. We're constantly talking to her, but who knows what she understands? After all, she doesn't even always respond to her name.

After a few minutes, we resort to asking another waitress to get our check for us. My wife has to shout to be heard over Tess's yells. We already have our coats on. The debris we've left under Tess's chair will require a steam cleaner and a team of at least four people to clean up. As I sign the check, I imagine what the waitstaff will do next time we come in here. One might say, "Oh no, these people? They destroy this place." And another might answer, "Yeah, but that makes them feel bad and tip well."

Back in the car, my wife and I ask each other what we always ask after a crash-and-burn dinner: (1) did you even taste your food? and (2) why on earth did we think this would be easier than staying home?

It's tempting to imagine an alternate universe, in which we have a typical four-year-old. My mind sometimes goes there, and I see what that dinner is like. Tess orders from the menu and tells us what she likes. She lets us know when she's ready to leave, but we're able to reason with her and buy a few minutes while we wait for the check. My kids are talking to each other. Maybe they're fighting and we have to separate them.

But I love this Tess, the one we have. These are the truths, and they are welcome ones: she is a typical four-year-old, because she got mad when she couldn't have the pizza we were all eating, she didn't like the lighting or the noise and wanted to leave, and once we were home she was happy again.