Christopher Shevlin's Blog, page 3

November 6, 2012

Guardian Masterclass

I’ve just been to visit the Guardian’s offices again and see their training rooms. Now I’m really looking forward to my Self-Publishing Step by Step masterclass. I’ve chosen a smallish room, to make it as easy as possible for everyone to talk, with a big window and a view over the canal, because I think everyone needs as much daylight as possible at this time of year. I should have taken a photo.

Everyone there is extremely nice, and there’s someone there for the whole weekend in case something breaks down – and also to give everyone a guided tour of the newsrooms at lunchtime.

I’m particularly looking forward to my two guests. On Saturday afternoon we have Orna Ross, founder of the Alliance of Independent Authors (of which I’m a member). I’ll be interviewing her (and everyone can join in) about why she went independent and why this is such a good time to self-publish. And on Sunday we have Fiona Robyn, author of the bestseller The Most Beautiful Thing. We’ll be talking to her about how she marketed her book in a way that felt easy and natural.

November 5, 2012

On not posting

I haven’t posted here for ages because I’ve been running courses in America, and after that I was caught up in a tremendous whirl of activity, including Upstairs Downton (http://www.facebook.com/UpstairsDowntonTheImproVisedEpisode). Now I am in another (slower) whirl of activity, preparing for my Guardian Masterclass at the weekend. Anyway, I just wanted to say hello, as I could feel bloggers’ block beginning to develop.

October 9, 2012

Another good review on Amazon

This appeared today on Amazon:

Really funny and pacy. Some of the writing is reminiscent of P G Wodehouse. Very witty and accurate descriptions of London mixed with complete fantasy.

There’s very little I like more than hearing that people like my book, especially when they have no reason to be nice about it. This reviewer is anonymous, but I’m pretty sure she’s not my mum. (Why do I think this is a woman? I don’t know. The soubriquet is ‘SR “Solipsist”‘, which doesn’t give much away, except for a good vocabulary. Then again, women have, on average, larger vocabularies than men, and they read more.) Anyway, thank you very much, SR. Your review is concise yet specific: a model of its kind. And I apologise if I’ve mistaken your gender.

P.S. Thanks too to S Beaton, whose Amazon review I’ve also just noticed. I’m very glad that TPAOJF has made it to Japan.

October 5, 2012

Quirky, absurd, whimsical

The Guardian review got me thinking about these words. In a way I’m surprised they exist, since there is very little in Britain that isn’t quirky, absurd or whimsical.

I was in Derbyshire last weekend, where I visited Chatsworth House, the ancestral home of the dukes of Devonshire (the earls of Derby, of course, live in Knowsley House near Liverpool). Here I found that the Sixth Duke of Devonshire had caused the local village to be moved about a quarter of a mile away because he felt it spoiled his view.

I then went to nearby Haddon Hall, where I found that the 600-year-old great hall had a manacle attached to one wall. Apparently, if a man didn’t drink enough at dinner, his wrist would be put in the manacle and the wine he hadn’t drunk would be poured down his sleeve*.

And that’s just two stately homes in the Peak District.

*Has anyone done any research on the effectiveness of sleeve-based penalties? I instinctively feel that even the most hardened criminal would mend his ways rather than have something poured down his sleeve.

October 2, 2012

Guardian review

Today I’m overjoyed by this review by the beautifully named Alfred Hickling in the Guardian:

Anyone suspicious that the publishing industry may be run by a small group of corporate-minded killjoys will applaud the DIY-ethic of Shevlin, who has published this quirky comic novel himself. The perpetually astonished hero finds himself in a conspiracy involving murder and the theft of cabinet-level documents, having done no more than give directions to a large man wearing a balaclava on the Holloway Road (mental note: men in balaclavas are either thugs or terrorists, unless they have very poor circulation in their ears). Shevlin’s offbeat brand of urban absurdism should appeal to anyone susceptible to Nicola Barker’s whimsy, though the penchant for made-up onomatopoeic verbs can become a bit trying: “scooshed”, “tocked” and “prunked” in a paragraph about parking a car. But you can’t help being tickled by Shevlin’s view of Covent Garden as a place “thick with mildly diverting notions which now had their own branded carrier bags”; or the Holloway Road afflicted by “the North London disease that turns any unwary building into a chicken shop”.

It should appear in the paper this Saturday, or possibly on next (i.e. the 13th)…

September 22, 2012

Low-key supernatural, part II

On Thursday evening I went to a pub called the Lamb, on Lamb’s Conduit Street. I was sitting in the low bit at the back, beside the door leading to the stairs (and thence to the lavatories and powder room). Kerry came back with our second drinks while I still had about an inch of my first, so she put it on the table next to me and sat down.

She told me that she had found out about the glass screen around the bar. It’s a very old pub which still has a lot of its Victorian features, including a raised frosted glass partition running all around the bar, with each pane on hinges allowing it to be opened so that you can speak to the bartenders. (See the picture below) Apparently it allowed the middle-class people in the left-hand side of the pub to avoid being seen by the working-class people in the public bar on the other side of the pub. Kerry told me this and then said, “It’s called a snob screen”.

As soon as she said these words my beer was knocked off the table and spilled all over the carpet at my feet. It was done neatly, avoiding my trousers and bag and leaving very little spillage on the table. In fact, there was a tidy ring of beer on the table, showing that the glass had been a bit over six inches from the two nearest edges. On one side of this ring, there was a trace of beer running perhaps three inches, as though the glass had been taken up from the side of the table nearest the door. All the rest of the beer was on the floor, along with the glass, which hadn’t broken.

I was frozen in place, waiting for my senses to supply an explanation – which usually follows when some surprising event happens. I thought I’d suddenly realise that I had made an expansive gesture without realising, or that someone had walked past. But no explanation followed. Neither of us had moved, no one had passed, the table wasn’t on an angle.

I went to the bar to replace my beer and told the barman what had happened. “Funny you should say that,” he said. “We’ve had five or six people tell us the same thing in the last few weeks.”

He still charged me for the new pint though.

August 30, 2012

I went to Gdansk and all I got was this lousy short story

Actually, the story isn’t all I got – I also got a ton of good memories.

I’ve just come back from Gdansk, in Poland, where I was doing Once Upon A Deadline – a writing event run by Hungry Arts as part of the Polish Arts Festival. It was one of the best weekends I’ve ever had, and I’m extremely grateful to Alex Gilly (@getalex) for mentioning my name to Robert Mac, the creator of the event – and also to Robert for including me and to Ros Green for making me welcome.

On the Saturday, each of the five writers involved was taken separately by a Polish guide to five different places: the Library of Gdansk, the shipyard where Solidarity began, a children’s playground, the Academy of Music, and St John’s Church. We spent about 90 minutes in each place, looking around and writing. The event began at about 9am, and by 8.30pm we had to have written a story of 2,000 words or less. The next day the stories were translated into Polish and read by their translators (mine was the excellent Polish prince, Piotr Ivansky) to an audience at the Gunter Grass Gallery.

My story was 2,250 words, cut down from the 3,500-word story below. The full set of stories will be published by Off_Press, and videos, photos and sound recordings from the day will be edited together in various forms, including an iPad app. A group of Polish writers will be doing the same thing in reverse in Southend this Sunday (2 September).

I’ll be writing a proper account of my weekend, so that I don’t forget it. In the meantime, here’s my story. It’s a bit odd, but here we go…

Free City

Have you ever walked into a room and realised that you have no idea why you are there? You stop, scratch your head, and then wander about, making vaguely purposeful gestures with your hands, hoping to remember what brought you there. It’s disconcerting.

Imagine then how much more disconcerting it is to stride out into a city, as George September did, and realise with a jolt that not only have you no idea why you are there, but also that you have no idea which city you are in. Or, indeed, who you are.

George looked around him in alarm. He was standing in a crowded shopping street. On both sides rose tall, thin houses with slim windows. Each house was different – some faced with brick, some with plaster painted in bright and elegant colours, like up-market children’s toys. At the end of the street a colossal church stretched up its tower like a finger to God.

George brought his eyes back to street level. Lining the streets were stalls selling jewellery. He moved closer to one, seeking its shelter. The jewellery was made of amber, glowing red-brown as though lit from within, rather than by the bright grey sky above. Behind the stall he glimpsed a model ship, also made of amber, in a window. And in that same window he met a pair of eyes. A man was staring at him: a man in his fifties, bald except for a little wisp of hair above each ear, and wearing neatly pressed trousers, a v-necked sleeveless jumper and a striped shirt – the clothes of a man who is trying not to be noticed. Growing self-conscious, George put his hand to his face, and – as the man in the window made the same gesture – he realised with a sudden pang that the man was not standing inside the shop, but was only reflected in its window, and that the man was George. ‘Oh,’ he thought. ‘I’m bald. And much older than I expected.’

Putting a hand in his pocket, George found a wallet containing a British driving licence. That was how he discovered that his name was George September. The wallet contained some money in a language he didn’t know, and no other clues whatsoever.

‘Brz bezinska-rodney vadny hodny lod?’ said the lady who owned the stall. Or at least that was what she seemed to say: he didn’t understand the language. She had obviously misinterpreted his reason for taking out his wallet and was eagerly pulling an amber necklace from the display case in front of him. He cast his eyes down. His instinct was to be silent, or possibly to run away. And then, unexpectedly, he looked shyly up at her. He smiled, pulled out his wallet and gave her some money. She smiled more enthusiastically, and gave him the necklace.

He walked on, bashful and afraid again. He needed a place to gather his thoughts, not to mention his identity, and work out how he was going to deal with this odd situation.

At that moment his eye caught the welcome sight, through a window, of books on a shelf. The building was light and clean and simultaneously new and very old. The sign above the doorway said ‘Bibliotek’. A library. He felt a rush of relief, almost of homecoming.

He climbed the stairs, pushed the door open and stepped inside. A white-haired man, dressed all in beige and sitting behind a large desk, looked up from the book he was reading and greeted George with a polite smile and a string of unintelligible words. George jumped, and only narrowly prevailed over his urge to claw open the door and run away.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘D-do you speak English?’

‘Of course. A little. How can I help you?’

‘I … I don’t know who or where I am.’

The man did his polite smile again. ‘I am Piotr – Peter. And this is special library dedicated to Gdansk – and the wider Pomeranian region.’

‘So I’m in Gdansk,’ said George. ‘And my name is George September.’

‘Yes,’ said Piotr. ‘So your problem is solved: you know who and where you are.’

‘But I don’t know why I’m here.’

‘This is something for each man to discover for himself.’

‘I suppose so.’

‘Do you want to know why you are here?’

George was taken aback by the question. Did he? After all, the place seemed beautiful and he seemed to have money. Perhaps he had come here to forget. Then again, what if he had a family? Someone might be worried about him.

Piotr smiled at George again. ‘Perhaps you do not want to know why you are here.’

George hesitated. ‘I do,’ he said at length. ‘I do want to know. What if I have family looking for me?’

‘A good point. This may seem a strange question, but tell me, did you chance to buy anything here in Gdansk?’

Thinking of his fumble with the necklace, George felt embarrassed. ‘No,’ he said.

Piotr’s face fell. ‘I’m sorry. All I can do is tell you where to find the nearest police station, so that you can declare yourself a missing person.’

‘Wait, no. Sorry. I was afraid you’d laugh at me. I bought an amber necklace. I don’t know why.’

‘Ah. This changes things. In this case, I advise you to put on this necklace and go to Mariacka – the very large church at the end of the street. I think you will find someone there who will guide you.’

‘But this is a woman’s necklace. People will laugh at me.’

‘They will not laugh. They will just look at you and think that you are …’

‘Strange?’ suggested George.

‘Yes, strange,’ Piotr agreed amiably.

George found himself back out among the jumble of people in the amber market. The library had not cleared his head, as he had hoped, but only made him more confused. Was Piotr playing a practical joke on him? George felt the necklace in his pocket, cold against his sweating palm. He could feel his face reddening just at the idea of putting it on. It would look absurd, a normally-dressed man like himself wearing a woman’s amber necklace. He imagined all these big German tourists around him, standing in a circle, pointing at him and laughing. He left it in his pocket.

Inside the church he stopped and gaped. The white-domed ceiling was so far away. The paintings were so old, so carefully wrought. The organ, massive and ornate, seemed to hover above his head as though suspended there solely by the word of God. George was insignificant. And this feeling was compounded by the German tour guide who absent-mindedly moved George out of the way so that he could explain the organ to his flock. George found himself standing next to a table where was moored an old man with a genial moustache who was selling tickets to the tower. George paid the ten zloty. He had no idea how much this was, whether the price of a piece of a chewing gum or a house, but he did it anyway.

George climbed innumerable stairs, at length passing beyond the ceiling and climbing up among the rafters and great steel beams, until eventually he arrived at a viewing platform. The city was laid out all around him, clustering near and neat around the church, with areas of green and trees further out, and then, in a distant dockyard, steel cranes stretched up, sniffing the air for signs of spring.

George remained there, alone with the sky and the city, for some minutes. ‘I’m so lonely,’ he thought. Blushing, he took out the necklace and put it on. After a while, his fear subsided a little. Nonetheless, when the staircase creaked, his hand flew to cover the amber bead that hung over his heart. He saw someone’s head, dark-golden hair, like the amber bead, and then he turned away. He put his hands in his pockets and stared self-consciously out at the cranes.

‘Excuse me. Are you George?’

He hadn’t noticed that she was standing next to him.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Yes. That is, I think so.’

‘I’m Maria.’ She paused nervously. ‘I’ll be your … guide.’

‘But I don’t know who I am.’

‘That is why you need a guide.’

Twenty minutes later, they emerged from a train onto an empty platform.

‘Up here,’ she said.

The bridge was steel, painted grey and blistered with rust. He followed her up the steps.

‘There is the shipyard,’ she said.

Beyond the end of the bridge stood two huge green cranes. The two great steel structures looked like birds standing over their young, feeding them. And in fact, at the foot of each of the cranes nestled a ship – almost complete, looking plump, contented and well-looked-after, surrounded by the comforting shouts of workers and buzz of machinery.

‘Twenty years ago, there were many, many more ships and cranes,’ said Maria.

‘What happened?’

‘I will show you.’

She led him along a road, past a gate guarded by a man with a white moustache, whose job seemed to be to bestow a smile, twinkle and kind word upon each visitor to this place – this place that seemed busy and abandoned at the same time. They passed a long building in the process of being demolished, which terminated suddenly in rags of torn timbers and frayed brickwork. They passed another with a sign saying that it had been the workshop of Lech Walesa when he had been an electrician ministering to the ships. And then, among a rank of warehouses, there was one with a smart glass front.

‘This is a gallery,’ said Maria.

They climbed some stairs and emerged in a huge room of brick and white concrete pillars. Through the large, grimy windows they could see the ships and cranes. She led him among the exhibits until they came to a white screen, on which a film was being silently projected.

‘It’s the destruction of the shipyard,’ said Maria.

He watched. He saw men cutting through a steel sign marked Stocznia Gdańska. He saw a huge machine grazing lazily on brick walls. He saw the giant cranes being cut loose from the docks and towed off to sea, no doubt to their deaths.

‘It was in these shipyards that people threw off their fear and set Poland free,’ said Maria.

‘And then the shipyards were destroyed,’ said George.

‘Yes, but not Gdansk. It always survives. It was completely destroyed in the war, you know, but it rebuilt itself. All those old buildings you saw around Mariacka were rebuilt from the rubble lying on the ground.’

They moved on to another exhibit. A rectangular metal block lay on the floor. Above it was suspended another metal block, hoisted up by a chain on each corner, fastened to the concrete pillars. From a distance it had looked ugly. But up close George saw that the two metal blocks were magnets, that between them was a black mass of iron filings, and that the iron filings had built themselves up into elaborate structures, gothic spires and towers. A beautiful and intricate city had formed naturally, of itself.

On the tram on their way back to the city, they passed a tall building, its front covered by a banner that said, ‘We will win anyway.’

When they had got off the tram, he turned to her and said, ‘Can’t you tell me where we’re going?’

‘What use is a tour guide if she spoils the surprise?’

‘But…’

‘Do you trust me?’

‘I want to. But I also keep wanting to run away.’

‘I can tell you how to run away, if you want. It’s very easy. Or I can help you to find out who you are. Will you trust me?’

She stopped to say this, and he stopped too and looked into her eyes. She was short and slight, in her early twenties, and dressed in jeans and a black sweater, her dark-golden hair tied up at the back. Her eyes were the colour of an angry sea. Despite her slightness, there was something strong and determined in her face.

They had stopped beside a playground, built between two tower-blocks of ordinary-looking flats. In the playground was a little house on stilts, with an orange pitched roof. Its picture-book perfection was only added to by its lack of walls and the bright-red slide that led from where its front door should be. Beside it a tyre hung from a chain, and a little girl sat in this swing, holding a solemn conference with two colleagues. A little distance away, a boy stood in the middle of a seesaw, operating it alone. And at the side of the playground, two adults sat in companiable silence on either side of another little girl.

‘All right then. Sorry,’ he said.

They walked on, past a church, until they reached a huge yellow-brick palace.

‘In here,’ she said. ‘This is the Academy of Music, where I study.’

The corridors that she led him along were quiet, almost deserted.

She ushered him into a darkened auditorium. A black piano stood in the middle of a stage, lit by a single spotlight.

‘Sit here,’ she said, directing him towards a chair that was off to one side of the stage. The chair was also lit by a single spotlight, which poured over it a soft and warm glow.

‘But shouldn’t I sit down there?’ He pointed at the rows of darkened seats in front of the stage, where a few people sat.

She said nothing, but went and sat down at the piano. She began to play. Quietly at first, constant and patient as raindrops.

‘Shouldn’t I sit down there in the dark?’ he asked.

She said nothing, only glancing at him, telling him with her eyes to sit and listen, continuing to play.

He hesitated, then sat in the spotlit chair and listened. Slowly, something new joined the music – something darker and louder, telling of fear and sadness, something impending, something happening, a disaster, and its passage into memory and regret. Behind it ran forever the constant flow of the piano’s raindrops, patient and consoling. A drip of rain landed on his shirt collar. His cheeks were wet. And he was crying. He didn’t know why. Only that he was sad, and he was hopeful, and that the hope made the sadness a little sharper, but also more bearable.

Later, they sat together in a church.

‘This is the last church in Gdansk to be restored. It is still not finished,’ Maria said.

‘Why did they wait so long?’

‘Some things take a long time.’

‘If it stood for so long without being restored, maybe it didn’t need it.’

‘Is that what you think? That if something has gone a long time without being changed, it doesn’t need it?’

‘I don’t know. No.’

She smiled.

‘Who am I?’ he asked.

‘You are a man who wanted very much to change, but found it very hard.’

‘Oh.’

‘Do you still want to know who you are? I was told to say that you won’t like what you find out.’

‘I do want to know.’

She handed him an envelope. He tore it open.

‘If you are reading this, then there’s hope for you – for me. I’m you, you see. I’m you and I am crippled with fear and timidity. I am afraid to reach out to people, afraid to live. I’ve been working in the same library for twenty-one years now, ever since I did that terrible thing. Once, years ago, I met a woman, Eve. It was the first time I had opened up to anyone. We got married and moved in together. I should have been happy. Then she got pregnant. All through her pregnancy, my fear grew – I was terrified of being a bad father. And then, before the child was even born, I couldn’t stand it any more and I left. I was too afraid of real life, so I went and got a job in a library and buried myself in books. I wanted to go back to Eve, but I was too ashamed and embarrassed. And so I never did. She went back to Poland, to Gdansk, and our daughter grew up there.

‘About a year ago I received a letter from my daughter. Eve, her mother had died of cancer. She wanted to meet her father for the first time. I wanted to see her too, desperately. But I knew that my fear and timidity would get the better of me – it took me six months just to reply to her letter – and that if we arranged to meet, I wouldn’t be there. In desperation, I had myself hypnotised. All I had to do was get on the plane. (I have had four attempts at this so far.) Once I arrived in Gdansk I’d forget everything, so that I could meet my daughter without fear. Isn’t that ridiculous? I set up a series of tests, little steps to prove that I had changed, that I could overcome fear and be a real person. Buying the necklace was the first test, wearing it was the second, sitting on a chair in public and crying was the third, and so on. Now we’ve come to the final test. I hope I don’t need to tell you what to do – after all, you are a much braver person than I am. Please do the right thing. My future is in your hands.’

George looked up. Maria was sitting there, her expression tense, the eyes that were the colour of an angry sea looked sad. What was he supposed to do? What could he say to her?

‘You’re my daughter,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ she replied.

‘I’m sorry I’m not the father you wanted.’

‘You still can be, Dad.’

August 21, 2012

The first bookshop copies go on sale

The Broadway Bookshop on Broadway Market in Hackney today became the first bookshop to stock copies of the Perpetual Astonishment. I took them a copy a couple of weeks ago, and when I went back on Saturday they said that their manager had really liked it. So, now they have two copies on the shelves. Coincidentally, I got my first order today from Bertram, one of the two biggest book wholesalers. (This might be for Foyles, who asked me for a reading copy a week or so ago.)

Used by thousands of bookshops across the country and carrying millions of titles, Bertram placed an order for one copy. And because my account with Nielsen is set up wrongly, I had to fulfil the order myself, which meant it cost me money. But if I get another order, Lightning Source will take care of it all.

Now I just need to summon up the courage to ask another nice local bookshop if they’ll stock the book.

August 17, 2012

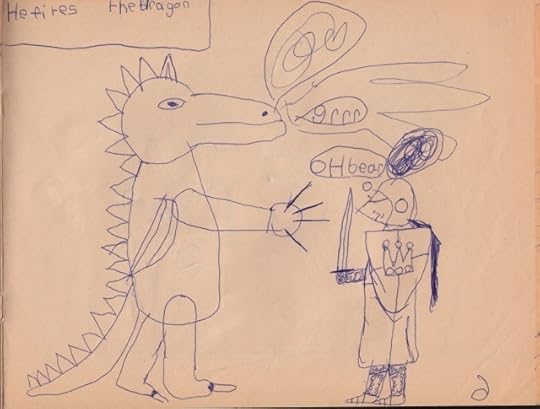

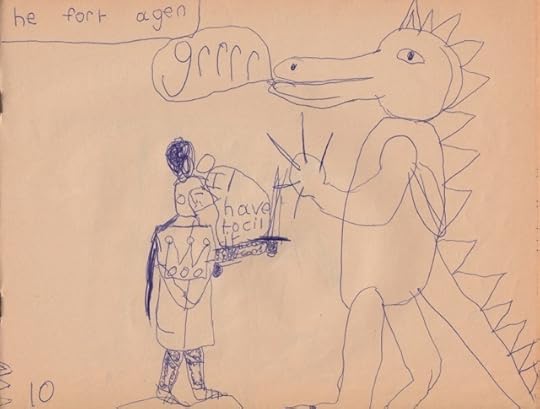

The Black Knight and the Dragon

This is the first of the two “other stories” from King Moonfred and his Knights and Other Stories.

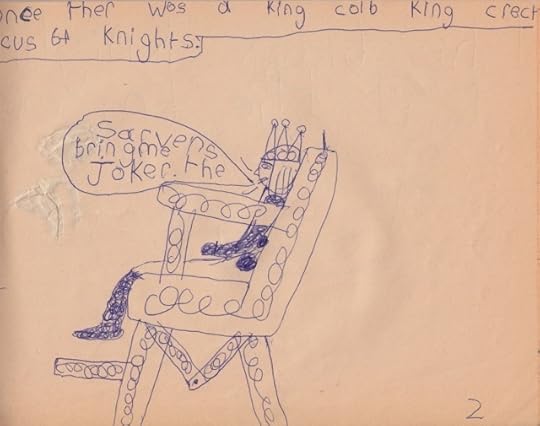

Cover page

Once there was a king called King Caractacus: 64 knights.

King: Servants, bring me the joker!

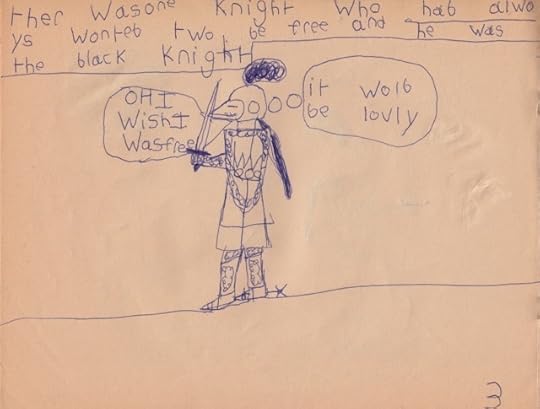

There was one knight who had always wanted to be free and he was the Black Knight.

Black Knight: Oh, I wish I was free. (Thinks: It would be lovely.)

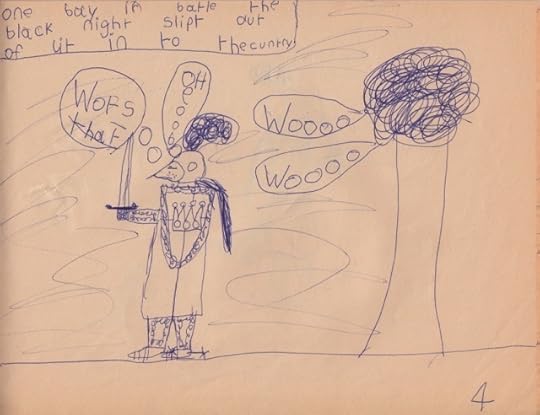

One day in battle the Black Knight slipped out of it into the country.

Black Knight: Oh good.

Wind in the tree: Woooo. Woooo.

Black Knight (thinks): What’s that?

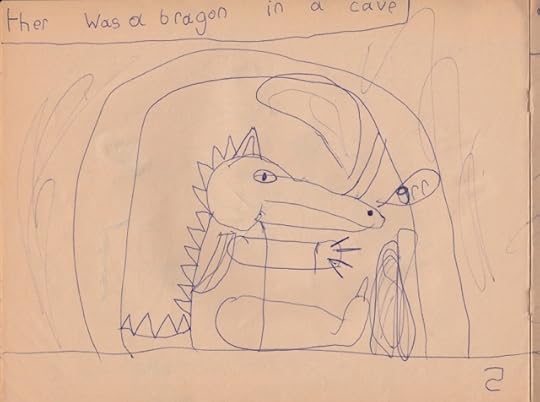

There was a dragon in a cave.

Dragon: Grr.

He fights the dragon.

Dragon: Grr.

Black Knight: Oh dear.

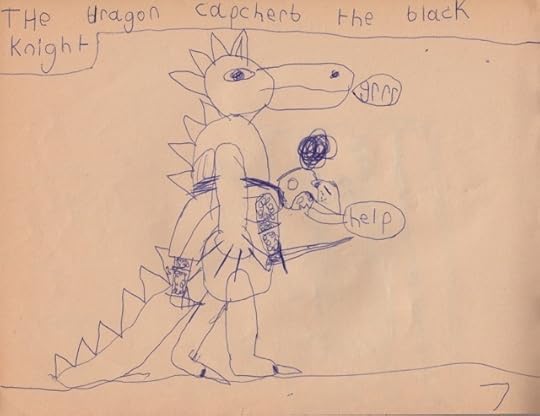

The dragon captured the Black Knight.

Dragon: Grr.

Black Knight: Help.

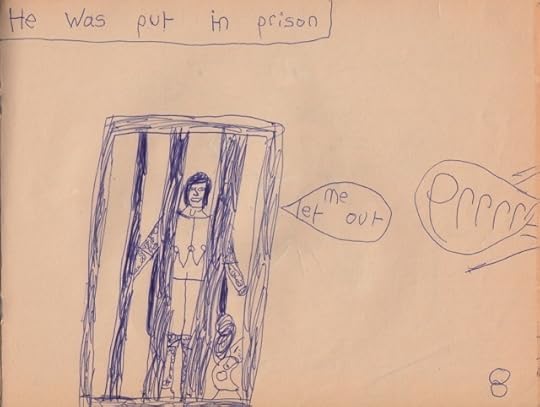

He was put in prison.

Black Knight: Let me out.

Dragon: GRRRR.

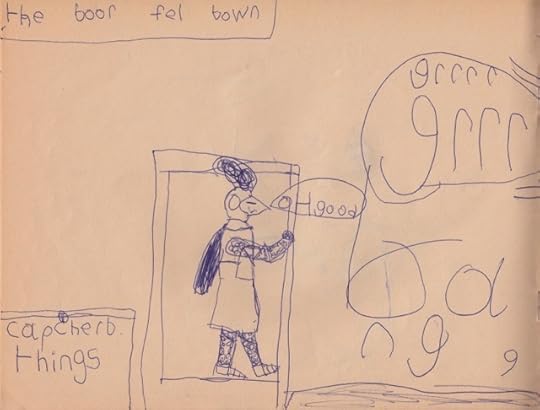

The door fell down.

Door: BANG.

Black Knight: Oh good.

Dragon: Grrrr. GRRR.

(The thing in the bottom left-hand corner is a chest labelled “Captured things”.)

He fought again.

Dragon: GRRRR.

Black Knight (thinks): I’ll have to kill it.

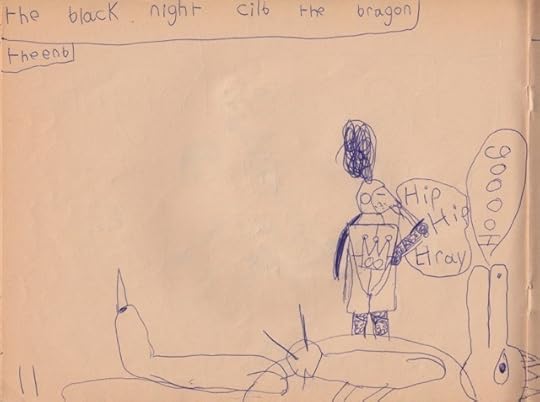

The Black Knight killed the dragon.

Black Knight: Hip hip hooray!

Dragon: Gooooh.

The end.

The Black Knight and the Dragon: a critical perspective

We begin with a formal echo of the opening of King Moonfred, with the king sitting on his throne, calling out for something he desires, in this case the jester. This deftly wrongfoots the reader, for the protagonist this time is soon revealed to be not the king, but one of his knights. The theme of the story is the existential question of freedom – and what better setting for exploring this than within the feudal system, whereby everyone belongs ultimately to the arbitrary and selfish king?

The protagonist takes advantage of the endemic warfare produced by this system and makes a bid for freedom. Shevlin immediately confronts us with the primal danger – represented in the form of a dragon – that keeps each of us from freedom. After a struggle, the dragon seizes the Black Knight (another existentialist element here: the author refuses us the easy option of a “good” hero, a White Knight) and deprives him once again of his freedom.

And then the door to the Black Knight’s cage falls open. What are we to make of this? Has some supernatural force intervened? Is it simply chance that the door’s hinges give out at this moment? Should we assume that the Black Knight has discovered within himself the resources required for self-liberation? The author supplies no answers, encouraging the reader to supply his or her own meaning – to become an active participant and collaborate with the text. In this, the core of the story, the Black Knight and the Dragon is functioning as a Zen koan. In a simple story spanning just eleven pages, the author pulls off a feat that took Camus many years and hundreds of pages to achieve.

In narrative terms, Shevlin sticks within the structure he has established for himself: an enemy stands in the way of the hero’s objective and must be fought not once but twice. The battles, seemingly between identical opponents in identical situations, nonetheless have very different outcomes. By ending at the very moment of the hero’s triumph, Shevlin encourages us to ask ourselves, “What next?” Has the Black Knight really attained freedom? What will he do with it? And is he, with the dragon gone, now alone?

The author elaborates on these fundamental questions even in the way individual letters and words are written. Why should words and letters always face the same direction, when pictures (and therefore people) can face left or right? Why should “b” and “d” convey different letters, rather than the same letter facing in different directions?

By raising an army of questions, the author vanquishes untruth.

August 15, 2012

Today’s Metro review

Well, I’ve now read the Metro review. Here it is:

★★★

Self-publishing has its successes, as EL James’s racy ebook series, initially posted on a fansite, proved. Yet there are reasons why editors and publishers exist, as demonstrated by Christopher Shevlin’s debut novel.

That’s not to say that The Perpetual Astonishment of Jonathon Fairfax isn’t a good book – it is and Shevlin was rightly picked up by the literary agency that represents the likes of David Nicholls. However, it could have been great: the comic hero is caught up in a murder plot that unravels into a political thriller, which is by turns absurd and engaging.

Although the plotting can be confusing, the perceptive one-liners reveal an author unafraid to laugh at the concept. At one point, Fairfax muses that reading a secret file makes him feel like he’s in a film, although only ‘the sort that would be on TV on a Wednesday morning’. Yet the same page has ‘she thought Kathy new what she was doing’ – the book is full of errors. Also, Fairfax’s bumbling astonishment at everything gets wearing – surely something an editor would have ironed out.

Ben East

My immediate reaction was to feel terrible because of the criticisms. But then again, I have what the NHS calls “Recurrent Depressive Disorder”, so my immediate reaction to pretty much everything is to feel terrible. I’m trying to teach myself to feel good about the good things and to accept the bad things for what they are. Luckily, I had some help in doing this with the review, because I almost immediately got this text from the wise and excellent Paul Tyrrell:

Hey Chris. Just read Metro review. Hope you realise the criticisms are totally outweighed by the “good book” comment! And nice of the critic to say you were “rightly picked up” by CB, yes? Brilliant. I may ask you to talk to the group about reviews now – sorry! Paul

…

Also note that you beat the Faber-published book on the same spread by a star!

I’ve had a little while to absorb the review now, and only one thing really hurts: “the book is full of errors”. The review copy I sent to Metro does have some errors in it, listed here (and including that weird “new” instead of “knew”). I’ve corrected all of these in the “full release” version of the book that’s been on sale since the beginning of August. It’s difficult to deal with this criticism without sounding petty, or as though I’m arguing with a critic’s perfectly fair point. All I will say is that doing things properly is very important to me, and that if anyone finds any more mistakes, please let me know. I’ve had two books published by big publishers, Pearson Education and Penguin. In the first of those books, the publisher’s proof-reader made no changes at all to my manuscript. In the second, the only changes were to do with house style (-ise vs -ize endings, and so on). I apologise for being petty, obsessive and defensive on this point. And I should have found and fixed those problems before 24 July, which is when I actually got round to it.

Anyway, I’m glad that Ben East thinks that the book is good and could have been great. And I’m sorry that the astonishment gets wearing – at least I warn readers in advance that the book is likely to contain a lot of it.

I also agree that publishers and editors exist for a reason, and I don’t have anything against them. I wonder whether, if the book had been taken up by a big publisher, it would have been much different. From what I hear, more and more publishers look to agents to do most of the editing work – mine certainly did a lot for me. I get the impression that, for big releases, publishers still put a lot of time and effort into editing. But for some other books, I hear that many of them do a surprisingly small amount.

We will never know. Nevertheless, I’m glad that I risked having my feelings hurt and put the book out myself. I’m glad that some people like it, and I’m sorry for its shortcomings.