Daniel Coyle's Blog, page 9

April 12, 2013

Why You Should Mimic More

We normally think of mimicry as a party trick. Which is is — but it’s also something more.

For an example, check out this skit from last week’s Saturday Night Live. It’s Bruno Mars doing dead-on impressions of Green Day, Justin Bieber, Steven Tyler, Louis Armstrong, and Michael Jackson (to save time, fast forward to 4:55 for the MJ).

Apparently Mars has been doing these impressions for years, starting with Elvis when he was a little kid. Think of what the repetitions of these imitations have done for Mars’s vocal technique, his range, and his ability to create certain vocal effects. Thanks to mimicry, he has a whole menu of sounds and moves to choose from and use.

I can testify that writers do this too. At various times in my notebooks I’ve mimicked Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, Frank DeFord, Gary Smith, and Kurt Vonnegut, and I know many others who did the same.

Here’s Novak Djokovic mimicking various opponents (his Rafa and Federer are especially good).

We instinctively want talent to be utterly original and one-of-a-kind. But the truth is, developing skill at mimicry opens a useful short-cut, because it allows you to test out proven techniques and add them to your repertoire. It also separates you from your ego, so you can make more reaches and take more risks.

The moral? Thou Shalt Steal, Mimic, Copy, Imitate, and Always Encourage Others to Do So.

April 9, 2013

How to Spot a Master Teacher: A Field Guide

You should read this story. It’s called “Every Good Boy Does Fine,” and it’s by Jeremy Denk, who happens to be a world-class pianist, but those details don’t really matter.

You should read this story. It’s called “Every Good Boy Does Fine,” and it’s by Jeremy Denk, who happens to be a world-class pianist, but those details don’t really matter.

What matters is that his story shines a bright, useful light into the role of the master teacher. Denk looks back over his lifetime and gives us what amounts to a greatest-hits album of insights that apply to all of us. (Bonus: here’s a great video of Denk talking about the story.)

For instance, here’s Denk quoting Mr. Leland, one of his first teachers:

“Practicing a passage is not just repetition but really concentrating and burning every detail into your nervous system.”

Later, Mr. Leland wrote this in Denk’s practice notebook:

“Welcome to the summer during which you will learn to hate me. We are going to do precision drills. Exercises in perfection of fingering, notes, and rhythm…. every slip means back to the beginning.” That was the summer the music died [Denk writes]. Long, tedious lessons solely on scales, arpeggios, repeated notes, chords. But this misery proved a success.

For me, the best parts were the descriptions of Denk’s unfolding relationships with his teachers. He remembers them with a novelist’s eye, picking out the key attributes, the practical and emotional tools they used to help Denk grow his talent.

In fact, Denk’s teachers turn out to be a beautiful set of case studies for analyzing what qualities master teachers tend to possess. I’ll list a few here:

1) Master teachers love detail. They worship precision. They relish the small, careful, everyday move.

2) They devise spectacularly repetitive exercises to help develop that detail — and make those exercises seem not just worthwhile, but magical. As Denk writes, “Imagine that you are scrubbing the grout in your bathroom and are told that removing every last particle of mildew will somehow enable you to deliver the Gettysburg Address.”

3) They spend 90 percent of their time directing students toward what is plainly obvious. They spend the other 10 percent igniting imagination as to what is possible.

4) They walk a thin line between challenging and supporting. They destroy complacency without destroying confidence. This is tricky territory, and requires empathy and understanding on both sides — particularly when it comes to understanding the moment when it’s time to move on.

5) They do not teach lessons; they teach how to work. As Denk writes, they “ennoble the art of practice.” (Isn’t that a fantastic phrase?)

I also like how Denk shows what the master teachers are not; namely infallible superheroes. Master teachers are master teachers because they’re good learners, constantly reaching to build the ultimate skill: constructing the talents of others.

April 5, 2013

A Quick Glimpse into the Future of Learning

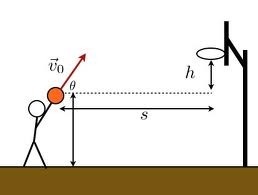

This clip got sent around last week among some top Olympic coaches, and quickly went viral in that community. As smart coaches do, they immediately started talking about how they might use this technology as a learning tool. Click it and you’ll see why.

At first impression, it just looks like a super-cool visual effect: guys using a homemade array of 15 cameras to achieve the famed “bullet view” from the Matrix movies. (As Keanu would say, Whooaaaa.)

Now imagine that, instead of biker-dudes doing flips, you used the array to capture:

A great guitarist navigating a Hendrix solo — showing the fingers, the wrist angle, the touch of each individual string

A downhill skier executing a series of slalom turns — zoomed in on the knee angle, the weight shift, the tilt of the ankle

A volleyball player executing variations of each basic move: bump, set, spike

An elementary-school teacher managing a classroom, handling interruptions, focusing attention

A salesperson making a pitch, using body language and expression to create engagement

We are all visual learners. Giving people the opportunity to stare at top performers in HD slow-mo, over and over, is exactly like handing them a blueprint.

The larger point: this kind of technology is only going to get cheaper and more available. Which means the deeper question is this: how are you going to use this stuff?

Also: the future is going to be really fun.

(Big thanks to John Kessel and Peter Vint for sharing.)

April 2, 2013

11 Rules for Better Writing

The other day I was asked to take part in a MOOC. If you haven’t heard the term yet, you will soon. MOOCs – Massive Online Open Courses — are speedily revolutionizing higher education, because they have the capability to deliver top-level teaching via the web to thousands of people, for free.

Anyway, this particular MOOC, taught by Professor Denise Comer of Duke University, is entitled English Composition I: Achieving Expertise. Seventy thousand people signed up, from Mongolia to Massachusetts, wanting to develop their skills. All of which got me thinking about writing, which might be the world’s most misunderstood talent.

Here’s the basic problem: people think that writing is this:

When in reality, it’s more like this:

This happens to be Proust, but it could be Orwell or Austen or Whitman or Hemingway, who wrote no fewer than 47 different endings for A Farewell to Arms. Point is, writing isn’t wizardry, and good writers are not superhuman. Building a story is not magic. It’s more like building a piece of furniture: you need quality wood, basic design skills, and lots of sandpaper.

So with that in mind, I’d like to offer the following carpenter’s rules that I’ve developed over the years. Some have to do with structure, others with practice, and all of them are 100 percent unscientific.

1) Know the difference between a topic and a story, which is this: A topic sits still, and a story moves. A topic is an answer, while a story asks a question that connects to the reader’s heart and mind. For example, I got fired from my job yesterday is a topic. I got fired from my job yesterday and this morning I began planning my revenge — that is a story.

2) Don’t fly solo. Find the best writers who’ve written in this vein and study them like a detective. Figure out how they attacked the problem. They are your coaches.

3) Figure out what your subjects/characters want — what they really, truly, deeply want — put it up top, and and let that question — will they get it? – fuel your narrative.

4) Inside the narrative, obstacles are your friend. The bigger the obstacle, the better the story.

5) Seek out opposites. For example, if you were describing something rough and crude, you should use images of elegance and refinement (i.e. “the abandoned Chevrolet was a lacework of rust”). Or, if a 330-pound defensive lineman enters a room, focus on how delicately and balletically he walks. Sentences are like batteries: opposites create energy.

6) Outline like crazy, and revise those outlines constantly. I use two kinds of outlines: big and small. The big outline is for the entire narrative arc; the smaller outline is for each chapter. Like construction blueprints, outlines sound dull, but in fact are the opposite: the place where the most important creative moves happen (Check J.K. Rowling’s outline for chapters 13-24 of Order of the Phoenix.)

7) Figure on a 10:1 efficiency ratio — that is, 10 pages of rough drafts and notes for every one page of quality writing. Which you’ll have to revise over and over again, of course.

8) Read like a thief. Underline good stuff, and read it over and over again until you figure out how they did that. When you find a passage, image, or description you love, write it down on a card and keep all those cards in one place.

9) Ignore small criticism.

10) Listen intently to big criticism. If someone doesn’t “get” your writing, it’s not their fault. It’s yours.

11) If you get stuck, get busy. Revisit outlines. Seek out new material. Keep plugging until something clicks. “Imagination” is overrated; creativity comes from making fresh connections.

A couple weeks, along with several hundred Ohio middle schoolers, I got to attend a writing competition called Power of the Pen. It works like this: students receive writing prompts, then have 40 minutes to write a piece, which is then judged. There were four rounds, and it felt like the NCAA tournament, partly because the kids write really well, and partly because there’s a team vibe, but mostly because the kids are not trying to be artists. They’re just building lots of stories, over and over, in a way that reveals the real nature of writing. It’s not an art; it’s a sport.

March 20, 2013

How to Overcome Fear of Mistakes: One Coach’s Story

Scientists call it the “sweet spot” — that highly productive zone on the edge of our abilities where learning happens fastest. The problem, of course, is that the sweet spot doesn’t feel sweet. In fact, it feels sour and uncomfortable, because being there you have to take risks and make mistakes. And most of us hate making mistakes.

Scientists call it the “sweet spot” — that highly productive zone on the edge of our abilities where learning happens fastest. The problem, of course, is that the sweet spot doesn’t feel sweet. In fact, it feels sour and uncomfortable, because being there you have to take risks and make mistakes. And most of us hate making mistakes.

Basically, we’re allergic.

But what’s kick-assingly powerful is when somebody finds a simple way to reverse that allergy. With that in mind, check out the following letter from Jared Mathes, who coaches a U-14 volleyball team in Calgary, Alberta.

The one problem I have on my team is having the athletes get over the fear of making a mistake. We do great in practice, but during a tournament, the more “important” the game, the more they regress to predictable, safe playing.

To overcome this, we discussed as a team a few weeks ago that the March 17 tournament would be a “throw-away”. We didn’t care about the outcome. If players played aggressive they would never be in danger of being subbed off, no matter how many mistakes they made. Everyone bought into the system and was willing to give it a try, except for about half of my parent group. They had a hard time accepting the fact that we were going to let the girls figure it out and let them “go for it” on every ball regardless of the score or the stakes.

As we started the day, we had serves going out and wide. But the team was relaxed and having fun. If they didn’t get a great spike in one rally, they tried even harder the next time. They saw that by making positive errors, often the other team would still go for the ball and touch it, giving us a point. As the day progressed, they were becoming more confident. I had athletes who had never attempted jump serving, trying it and succeeding. Our play was getting more aggressive as the day went on and we were constantly winning.

We made it to the semi-finals and all of my doubting parents were congratulating me on the genius of the approach to the tournament. They couldn’t believe how well their daughters were playing, and it was just getting better. I cautioned them and reminded them that the focus has to be on the process, not the outcome, and that even if we were in last place, it would still have been a worthy strategy for all the teaching it provided. We played with the most aggression and intelligence we have ever done. We hit from everywhere on the court. It was beautiful to watch.

In the second game of the finals, we were behind 23-19. My athlete who was up to serve was one who had discovered her jump serve throughout the day. In the past, she would have regressed and underhand served because she had no confidence in her overhand serve during a critical time in the match. However, with no fear of messing up, and having the entire bench and coaching staff cheering her on to “go for it!”, she let fly an amazing jump serve. Ace! The score is now 23-21 for them. She goes up to do it again. I look over and her mother is covering her eyes. This player has never served 2 jump serves in a row and her mother can’t watch. We’re all cheering her to go for it. Again, Ace!. Score is 23-22 for them. Confidently, she goes back to serve again. She ends up serving 3 more aces, all off of her newly found jump serve and we win the tournament. The bench is going crazy and the parents are ecstatic. I think her mother suffered a minor heart attack.

After we clear the court I gather the team around and ask her in front of all the players how it felt to “go for it!” when we were down by 5 and ended up winning the match and the tournament! With tears in her eyes, all she could say was “It was awesome!”

Sincerely,

Jared Mathes

I love this story for a bunch of reasons, but mostly because it shows the power of redefining failure: of providing a space where mistakes aren’t merely tolerated, but seen as a productive, essential part of the process. Positive errors – what a wonderful term.

The other takeaway, I think, is this: coaches and parents are storytellers. Their job is to create an emotional safe zone where players can go to the edges of their abilities and then beyond. Jared’s wisdom was to change the story — this is a throwaway tournament — and that nudged his players into the sweet spot.

Which, as they discovered, is pretty freaking sweet.

(Big thanks to the great coach and teacher John Kessel for sharing Jared’s letter.)

March 15, 2013

The 7 Rules of Napping

I was brought up in a family of world-class nappers. My father was legendary for his seemingly effortless ability to attain the holy grail of napping: the three-hour Sunday snooze. My mother took the micro approach, stealing catnaps on the living room floor without a pillow. This resulted in a recurring scene: my brothers and I coming home from school to the unnerving sight of dear old Mom laid out unconscious on the carpet, arms splayed like a CSI victim. Then she’d spring up to greet us, the imprint of the weave still on her cheek. It was like living with Lazarus.

I was brought up in a family of world-class nappers. My father was legendary for his seemingly effortless ability to attain the holy grail of napping: the three-hour Sunday snooze. My mother took the micro approach, stealing catnaps on the living room floor without a pillow. This resulted in a recurring scene: my brothers and I coming home from school to the unnerving sight of dear old Mom laid out unconscious on the carpet, arms splayed like a CSI victim. Then she’d spring up to greet us, the imprint of the weave still on her cheek. It was like living with Lazarus.

It turns out Mom and Dad were ahead of the curve. We are living in the Golden Age of the Performance-Enhancing Nap: neurologists are touting the learning benefits of midday siestas; Silicon Valley companies are competing to see who can design the hippest nap rooms. Napping is not just napping anymore; it’s a skill. So with that in mind, I’d like to offer the following rules.

Rule 1: Take your shoes off. Leaving shoes on for a nap is like wearing a swimsuit in the shower: just because you can doesn’t mean you should. This is not about being efficient — it’s about scoring a high-quality unconsciousness, and that means getting comfy.

Rule 2: Get horizontal. Yes, truck drivers and astronauts can nap sitting up. But you are not an astronaut. Even Thomas Edison, a workaholic who liked to boast that he only slept four hours a day, obeyed this rule, clearing off his workbench and stretching out like a champ. Plus, getting horizontal lets you fall asleep 50 percent faster than sitting; it’s the cue that tells your body, this is for real, dude.

Rule 3: Get under a blanket. Napping slows your metabolism; you naturally tend to get chilled. The trick here is to have a blanket that’s not too heavy, and not too light. A medium blanket — like an afghan — lets you cocoon without getting too warm or cold. A hoodie works in a pinch.

Rule 4: Aim for the sweet spot of 20-45 minutes. Go longer (like my dad usually did) and you are moving past the nap zone into the the zombie zone — the kind where you find yourself unable to fully wake up again for hours. While this creates ample entertainment opportunities for others (“Hey, let’s switch the clocks ahead, cook pancakes, and trick Dad into thinking it’s morning”); it’s considerably less productive for the napper.

Rule 5: Aim to nap after lunch. The Spanish figured this out a long time ago: just after lunch is when your body is in a natural down cycle. Stop resisting and embrace the fact that an afternoon yawn is the equivalent of a flashing neon sign: TIME TO ZONK.

Rule 6: Avoid using wake-up gimmicks. Salvador Dali held a key in his hand so that he would awake when it clanged to the ground. But this is a terrible idea (unless you are a surrealist and want to paint a lot of melting clocks). These tricks only serve to end the nap before you get to the good stuff — the short, deep sleep cycle, where you awaken after 20-45 minutes. Instead, set a backup alarm on your phone for 45 minutes.

Rule 7: No bragging about what a great nap you just had. Just take it in stride. The rest of us can tell anyway.

March 12, 2013

Steal This Idea, Please

You might recall last week’s post about an Illinois teenager named Torin Bakke, who recorded his improvement after 200, 1,000, and 3,000 hours of clarinet practice. So when Torin wrote in to say hello, I couldn’t resist asking if he had any advice he might want to share. Here’s what he wrote:

You might recall last week’s post about an Illinois teenager named Torin Bakke, who recorded his improvement after 200, 1,000, and 3,000 hours of clarinet practice. So when Torin wrote in to say hello, I couldn’t resist asking if he had any advice he might want to share. Here’s what he wrote:

“I think the most important thing is just making yourself practice every single day. If you take one day off, it’s easy to take the next day off, and then you’ll stop progressing and get really frustrated.”

There you have it: Every single day. So simple to think, and so tough to do.

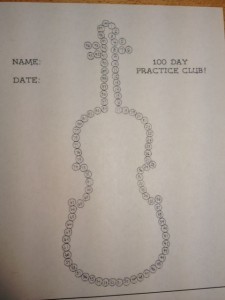

As fate would have it, one day later my wife Jen came across a useful Torin-esque tool: a practice map. It could not be more straightforward: 100 little circles, each representing an individual day, drawn in the shape of a violin (click on the image to zoom in). It’s from the Suzuki Music community, and it’s used by kids who want to make the 100-Day Club — which requires practicing 100 consecutive days. (In Suzuki, that makes you kind of a rock star.)

I love two things about the practice map: 1) it gives the learner ownership of the process, and 2) it points toward a larger goal. Each day is literally part of a bigger picture. In other words, repetition isn’t really just repetition — it’s construction.

The other thing I love is that it would be so simple to make other practice maps: a soccer ball, or a ballet shoe, or a trophy, or a straight-A report card. So by all means, feel free to steal this idea. (And, as always, to share any similar ideas or methods you might have.)

March 8, 2013

The One Word You Shouldn’t Use With Your Kids

My friend Henry is a great teacher. He’s taught the advanced science classes at one of California’s most high-performing middle schools for about a decade. The kids in his class are bright, hugely motivated, and high achieving — or, as the school calls them, gifted.

Which is precisely the problem.

“Every year is the same,” Henry says. “The kids walk in on the first day of school and they are convinced they’re brilliant and can solve any problem. It takes a solid month to relieve them of that idea, to show them how much they don’t know, and how hard they really have to work. Then we start making progress.”

“Gifted,” he says. “I don’t like that word.”

Me neither. Not in sports, not in school, not in anything. I’m starting to think it’s the cultural equivalent of high-octane junk food — a convenient, sugary idea that creates an artificial ego boost (mostly for parents), while leaving behind a quiet, substantial cost.

In fact, you can add it up:

1) Kids who are told they’re gifted tend to take fewer risks. Being called gifted grants kids a status worth preserving. Why take any risk that could jeopardize that status? (Check out the research of Carol Dweck if you want more on this.)

2) Kids who are told they’re gifted tend to produce less effort. Why should they, if they’ve already achieved the desired status?

3) Kids who are told they’re not gifted are demoralized. Why should they try hard and risk failure, if they don’t really have control over the outcome?

4) Studies show that a surprising majority of prodigies end up reverting to the mean. In addition, our best predictions about who will succeed and who will fail turn out to be consistently, colossally wrong. (For examples, read here and here.)

The deeper problem here is practical. The idea of the Gifted Child is baked into our culture, and so we haven’t developed a handy vocabulary for telling the deeper, more complicated story — a story that has to do with resilience, character, opportunity, social support, and, above all, effort. So here are a few ideas to help you avoid using the G-word.

Don’t say anything. Except for the fact that it feels sort of nice, there’s no compelling reason to label anybody “gifted.” So don’t.

Praise kids for their effort, and the time they put into preparation.

Use words like “proficient” or “experienced” or “high-mastery” — all of which are kinda clunky, but which at least avoid the “born magical” vibe.

Another way: design learning to promote mastery. At my daughter’s school, students are permitted to re-take math tests over and over (for one week) until they achieve a score 90 of or above. Which sounds crazy, until you see kids who scored an 75 or a 85 diving back into a test, excited to improve. Used this way, tests stop being a verdict, and start functioning as a lever for more effort and progress.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that we’re all created equal. Genes do matter. There are certain people who perform way above the norm. But the gifted child narrative is wrong because it takes the spotlight away from the real gift: the fact that developing talent isn’t a lottery you win, but an effortful process that you can control.

March 6, 2013

Our Weekend at the Sports Nerd Super Bowl

This past weekend my 17-year-old son Aidan and I traveled to Boston to attend the Sports Nerd Super Bowl, also known as MIT’s Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. It’s the year’s supreme gathering of scientists, coaches, scouts, team owners, and others who are obsessed with capturing and understanding the hidden metrics that drive performance.

This past weekend my 17-year-old son Aidan and I traveled to Boston to attend the Sports Nerd Super Bowl, also known as MIT’s Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. It’s the year’s supreme gathering of scientists, coaches, scouts, team owners, and others who are obsessed with capturing and understanding the hidden metrics that drive performance.

Here’s what we learned, in the form of DOs and DON’Ts:

1) DO NOT attempt to challenge a basketball-playing robot to a free-throw shooting contest.

2) DO attend late-night Chianti-fueled Italian dinners with British soccer scouts and U.S. Olympic talent-development researchers, who are among the most entertaining and insightful humans on the planet.

3) DO NOT, under any circumstances, choose the vegetarian option for the boxed lunch (which may have been assembled using spare parts from the aforementioned robots).

4) DO accept the fact that your future is all about embracing big data.

Sorry, I should have typed BIG DATA, because that’s the way it feels. The analytics avalanche triggered by Moneyball continues to accelerate and widen, and is now on the verge of taking over many aspects of training, scouting, coaching, and performing — exactly the same way that it’s making fundamental changes in the way we approach business and education. (As if to prove it, on the plane ride home I sat next to an educational consultant who was reading Driven by Data.)

We are all living in Dataworld, where nothing is sexier than massive piles of raw information. Did you know, at most NBA games, six specialized cameras hang in the rafters to capture every dribble, every acceleration, the precise arc of every shot — and convert that data into terrabytes of useful strategic information? Or that it’s possible to use retinal tracking to predict which soccer players are the most effective passers? Or that you could write a paper entitled “The Algorithmic Taxonomy of Basketball Plays from Optical Data” and actually be considered kind of a rock star? (If you’re curious, I’d recommend touring the website).

For me, however, most fascinating part had to do with the mysterious places Big Data can’t yet go — motivation, heart, team culture, work ethic, leadership, friendship. In short, the Soft Stuff, the black box of emotions and communication and that powerful force-field we call “culture.” As former NFL coach Herm Edwards said in one panel, “Numbers are numbers, but people play the game.”

It’s true. We are social animals, driven by emotional forces we don’t understand. No amount of analytics can explain how broken relationships can destroy a team’s chances to succeed. Likewise, there’s no algorithm that explains how a combination of selfless players, with the right leadership, can become far more than the sum of their parts.

In fact, most insightful piece of information I heard all weekend came not during the conference but during that late-night Italian dinner in Boston’s North End. It came from a highly experienced soccer scout for a large English team, who had spent most of the past decade traveling the world trying to find out which nameless 13-year-old might have a shot at becoming the next Messi or Ronaldo. He was a brilliant guy who understood all the analytics. But the advice he shared had zero to do with numbers.

“At every level of sport there are four types of players,” he said, holding up four fingers. “Sheepdogs — the leaders, the guys who call the tune. Sheep — the ones who follow where they’re led. Corpses — who just lay there, who aren’t going to really try — and Terrorists, the ones who will undermine the coach and destroy your team if you give them the chance. So to have a good team, you need to find sheepdogs and sheep, and get rid of the corpses and terrorists.”

Around the table — a table filled with scouts and talent-development types — heads started nodding. Yes! In those four words — sheepdogs, sheep, corpses, terrorists — the scout had neatly explained the dysfunctional culture of the Red Sox, the Yankees, the Lakers, and all the other super-talented teams that had failed to perform. I started thinking of all the teams I’d ever been involved with, and the pattern fit — the teams with sheepdogs and sheep succeeded, the ones with corpses and terrorists imploded.

I love Big Data. But the Sheepdog/Terrorist Rule is information that I can really appreciate.

February 28, 2013

How to Stop Being Allergic to Practice

The main problem with practice is that we all have a powerful instinct to avoid it.

There’s a perfectly good reason for this: your unconscious brain. Practice involves spending lots of energy struggling for an uncertain payoff, and your unconscious brain really, really dislikes spending energy for uncertain payoffs.

After all, evolution built your brain to behave like an ultra-conservative banker — investing energy only when there’s a clear, tangible benefit. As a result, we’re all natural-born geniuses at coming up with excuses not to practice, or to cut corners, or to skip it and hope things work out.

All of which is why you might want to check out these three videos by Torin Bakke, a teenage clarinetist from Illinois. Back in 2009, when he was 11, Torin had an idea: he started tracking his hours of practice, and videotaping himself at each new benchmark. (For more, here’s Torin’s blog.)

So here’s Torin at 200 hours (okay, he sounds decent for a beginner)

And at 1,000 hours (wow, he’s made a massive leap)

And at 3,000 hours (holy sh*t!)

I like Torin’s method because it’s 1) simple to do, and 2) it provides a nice way to highlight the payoff of progress. Seen day to day, progress feels like frustratingly slow baby steps. Seen with this method, the cumulative power of those baby steps is crystal clear.

Here are a few other ideas I’ve seen people use to defeat their practice aversion:

Be like Torin: Make a habit of tracking progress, using journals or video.

Be early: Build a habit of practicing early in the morning, so nothing can get in the way.

Build “on-ramps”: Surround yourself with behavioral cues that nudge you toward practice. If you’re a runner, keep your running shoes next to your bed, so you put them on each morning. Same with violin, or soccer ball, or math book — the point is to design your space so that practice can happen with a minimum of willpower.

Finally, does anybody else know of other people who are tracking their practice and recording their progress in this way? If so, I’d love to hear about it.