David Blixt's Blog, page 5

June 23, 2015

HNS Preview II - Sword Parts and Types

June 22, 2015

HNS Preview - Basic Combat Terms

Ahead of the Historical Novel Society Conference this weekend, I thought I'd throw out some basic combat terms as a resource for participants. So here are a few essential definitions:

Baldric (Baldrick) ��� A belt or girdle usually of leather that supported the wearer���s sword and scabbard.

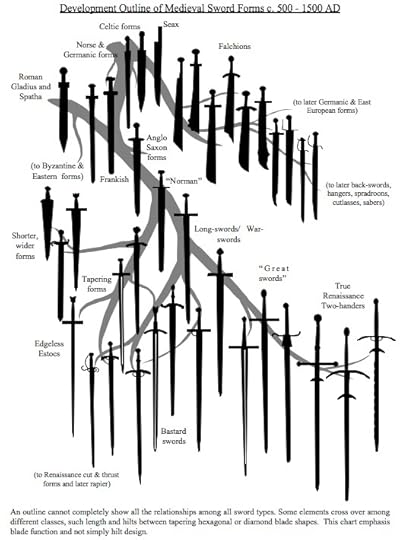

Bastard Sword (also Hand-and-a-Half Sword) ��� A contemporary term, now meaning a sword that can be used one or two handed.

Battement (Fr) ��� A beat attack, a controlled tap with the forte or middle part of the blade against the middle or foible of the opposing blade to remove the threat or provoke.

Bind ��� An attack on a parried blade, moving it two places, or 180 degrees.

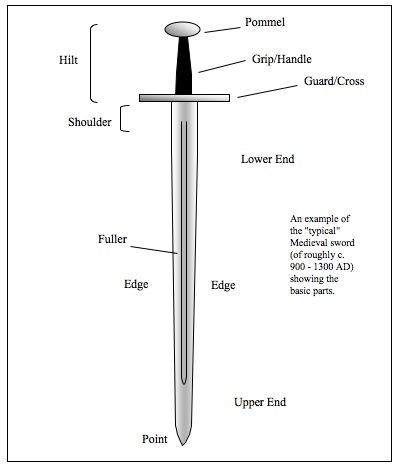

Blade ��� The essential part of a cut and/or thrust weapon that covers its entire expanse. The basic blade is broken down into the following parts: tip, foible, middle, forte, shoulders, and tang. Many blades, like the rapier, have a ricasso between the forte and the tang. The cutting edge is divided into the true edge and the false edge.

Block ��� a) a defensive action used to stop or deflect an oncoming attack; b) a parry

Blood Groove (also Blood Gutter) ��� A complete misnomer created to explain the grooving and/or fluting of a blade, which falsely supposed these grooves were devised to allow the blood to flow from one���s opponent. See Fuller and Fluted Blade.

Breaking Ground ��� Any action of footwork that surrenders ground to the opponent.

Broadsword ��� a) a term now applied to almost all swords of the Medieval period; b) a 17th century term used to distinguish small swords (ep��es and foils) from cavalry or basket-hilted swords.

Buckler ��� A small round (sometimes square) shield generally used in conjunction with the broad bladed swords of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. The buckler and short sword were the national weapon of England until the late 16th century.

Case of Rapiers ��� Twin rapiers. A slightly decadent style of rapier play involving the use of a rapier in each hand. Often designed to be carried in the same scabbard.

Changement ��� The practice of changing, joining, freeing, removing, and replacing the blades. Any action of the blade, from free or engaged guard position, that moves the blade to a new line of engagement. Each type has a different name and function.

Close Quarters ��� When two combatants are inside normal measure.

Cobb���s Traverse ��� Euphemism for running away from a fight, running backwards, or back-pedaling from an encounter. Named for and Elizabethan fencer and brawler.

Cold Steel ��� Slang for a cut and thrust weapon, now applied to any sharp sword.

Corps-��-Corps (Fr) ��� Literally ���body-to-body���. An action in which there is body contact or where the blades are locked together and distance is closed.

Cut & Thrust ��� A weapon suitable for attacks with both the point and the edge

Cut ��� A stroke, blow, or attack made with the edge of the blade.

Cutting Edge ��� The sharp, true, or fore edge of any blade.

Dagger ��� a) a short, stout weapon like a little sword, with a blade designed to both cut and thrust, a Poniard; b) the offensive and defensive weapon used in the left hand (the ���main-gauche���), along with a sword or rapier.

Draw ��� a) to remove one���s sword from its scabbard for the purpose of either offense or defense; b) a call or challenge to fight.

Duel ��� a) a formal fight between two persons ��� single combat. A private fight, prearranged and fought with deadly weapons, with the intent to wound or kill, usually in the presence of at least two witnesses, called seconds. B) a trial by wager of battle ��� judicial single combat.

Dueling Punctilio ��� The strict rules that governed all aspects of a duel from the issuing of the challenge to the fight and/or reconciliation.

Duello (It) ��� The established code and convention of duelists.

En Garde (Fr) ��� The basic position assumed by a combatant when fencing. Usually Terza (3).

Engage ��� a) to cross swords, interlock weapons; b) to entangle, involve, or commit to undertake a quarrel or fight.

Envelopment ��� An attack on the enemy blade which transverses a complete circle to return to its original position.

Ep��e Blade ��� A triangular blade, fluted on three sides for lightness, approximately 35 inches in length, tapering evenly from forte to tip. Developed from the 18th century small sword, becoming in the 19th century a weapon of sport. Originally called the ���esp��e���.

Escrime (Fr) ��� The French word for fencing.

False Edge ��� The edge of the sword turned away from the knuckles of the sword hand.

Feint ��� A false attack, either cutting or thrusting, meant to deceive or humiliate the opponent.

Flat ��� The wide portion of the blade.

Flute (also Fuller) ��� The groove, channel, or furrow found in blades such as the small sword that removes precious ounces from the blade���s weight without jeopardizing its structural integrity.

Foible (Fr) ��� (17th century French for ���weak���) ��� The uppermost, and weakest, third of the exposed blade closest to the tip.

Foil ��� a) a light weapon in modern fencing; b) Elizabethan for any bated, blunted, or dulled weapon.

Forte (Fr) ��� The widest and strongest third of the exposed blade closest to the hilt, the part used to block or parry.

Gauntlet ��� a) an iron glove to protect the weapon-bearing hand; b) leather fencing gloves

Grip ��� a) the manner in which the weapon is held; b) the part of the sword situated between the guard and the pommel.

Guard ��� a) the fundamental position of the combatant preparatory to action of an offensive and defensive nature (most commonly in the guard of Terza) b) the portion of the weapon that protect the fingers or hand. See also Quillon and Knuckle-Bow

Hilt ��� A portion of the weapon comprised of three parts ��� the guard, the grip, and the pommel. The haft or handle of any weapon.

Invitation ��� Any movement of the blade or arm intended to tempt the opponent to attack.

Knuckle Bow ��� Branch of the sword-guard that sweeps from the hilt to the pommel in a bow shape to protect the sword-hand.

Lag Foot ��� The foot in the rear or back position at any time in footwork.

Lead Foot ��� The foot in the forward position at any time during footwork.

Linea (It) ��� The lines of engagement: alta (high), bassa (low), esterna (outside), interna (inside).

Longsword ��� A sword with a simple cross-hilt and a long cutting blade.

Mollinello (also Moulinet, literally ���like a windmill���) ��� The action of pivoting the blade from shoulder, elbow, or wrist in a circle, either in a clockwise or counter-clockwise motion. Creates either a circle on one side of the body (or overhead), or else a figure-8 across the body.

Montante ��� (literally ���rising���) An uppercut, a rising vertical cutting attack with the true edge. Usually to the groin.

Moulinet (also Mollinello, literally ���like a windmill���) ��� The action of pivoting the blade from shoulder, elbow, or wrist in a circle, either in a clockwise or counter-clockwise motion. Creates either a circle on one side of the body (or overhead), or else a figure-8 across the body.

Parry ��� a) defensive action of a bladed weapon where the forte opposes the foible of the attacking weapon, stopping the attacking blade at its weakest point with the strongest part of the defending blade; b) to ward off or turn aside an offensive blow or weapon by opposing one���s own weapon, hand, or other means of defense.

Passado ��� An English spelling of either Passada or Passata; a forward thrust with the rapier, accompanied by a pass.

Passata Sotto (It) ��� (literally ���pass beneath���) ��� A thrust while either dropping the leg foot back or driving the lead foot forward, while the free hand is placed on the floor or ground, creating a tripod.

Pommel (from the French pomme, meaning ���apple���) ��� a) the metal ficture that locks together the different parts of the weapon and acts as a counter-weight to the blade; b) to strike, beat, or attack with the pommel of the weapon instead of the blade.

Poniard (also Main Gauche Dagger) ��� Form of quillon dagger developed during the 16th century, designed to be held in the left hand with the point up, like a sword. These had guards with quillons and a side-ring, serving as protection for the knuckles.

Pronation ��� The position of the sword-hand where the palm is turned down, nails of the sword-hand facing the floor.

Punto (It) ��� Literally ���point��� or ���tip���. The point of the weapon.

Punto Reverso ��� An arcing attack to the opponent���s right buttock/hamstring.

Quillons (Fr) ��� One or both of the arms or branches forming the cross-guard of a sword, providing the sword-hand with a protective barrier and preventing the opposing sword from striking the hand.

Rapier and Dagger ��� the fashionable style of swordplay during the latter half of the 16th century and into the early part of the 17th. The rapier was the main attack weapon, used in the right hand, while the dagger was mostly defensive, used in the left.

Rapier ��� Long, thrusting sword developed in Italy in the 1480s. Originally used for both cut and thrust attacks (and poorly designed for both), it became a weapon chiefly used for thrusting. In an attempt to protect the sword-hand from injury, over a hundred distinct hilt configurations were developed.

Ricasso ��� An unsharpened length of blade just above the guard.

Sabre (Saber) ��� A heavy sword with a curved blade (very effective in cutting attacks), and a simple hilt configuration used by the cavalry of all European nations in the 18th and early 19th centuries. One who fights with a sabre is a sabreur.

Scabbard ��� Case or sheath which protects the blade of a weapon when not in use.

Single Sword ��� Any sword light enough to be used in one hand, for both offense and defense.

Supination ��� The position of the hand when the palm is turned upwards, with the nails of the sword hand pointing toward the ceiling.

Swash ��� To make the sound of clashing swords or sword and shield. Hence the origin of the phrase ���swashbuckling��� ��� hitting one���s sword against one���s buckler. Came to mean a swaggering bully or ruffian.

Tang ��� (originally the ���tongue��� of the blade) Portion of the blade that extends from the forte and shoulders, passes through the guard and grip, and fastens into the pommel.

True Edge ��� The cutting side of the sword, on the same side as one���s knuckles.

As promised, I will have a 200-page book with essays, diagrams, and a glossary for sale exclusively to conference-goers for $20, available directly from me. But it's hardly essential to taking the class. See you in Denver!

June 19, 2015

Write and Fight Right

A week from today I'll be in Denver, leading 60 authors through their paces with Broadswords, Rapiers, and Smallswords at the Historical Novel Society Conference. It's quite an honor, and I'm hugely excited. Because the more writers understand about fighting, the better they can portray it on the page. But combat was not restricted to mortal matters. As I tell writers of historical fiction, you might not know you're writing about swordplay, but you are.

From antiquity to the late 19th Century, swordplay was at the center of the world. I don���t mean just duels and warfare. I mean customs and society. The way a man bowed. Why we shake hands in greeting. The reason men���s and women���s shirts button differently, even to this day ��� all of this came from swordplay.

Dance is especially important in the history of swordplay. Or rather, swordplay is vital to understanding the history of dance. In a dangerous world, a man had to always remain in practice. So the dance of any given period reflects the fighting style of that period. In the time of longswords, with big sweeping steps and long arcs, the dance is the reel. In rapier-and-dagger fighting of the Tudor era, dance partners held up both hands and switched from one to the other, just as in a rapier duel. The delicate footwork and correct posture for smallsword fighting is exactly mirrored in the 18th century waltz.

The dance of a period comes out of the fighting style of a period. In fact, it is not until we introduce repeating guns that this trend ends (it is also the end of couples-dancing ��� ever since we started using automatic weapons, men and women have ceased to dance together).

This is what I mean when I say you���re writing about swordplay. A woman walking on a man���s left in public was to keep his sword-arm free. The length of the sword in Elizabeth���s court was a strict 33-inches, because men kept wearing longer and longer swords (overcompensating?) and were constantly whacking each other when they turned.

And language! So many phrases we use today stem from violence. Cloak and dagger. Let the cat out of the bag. Lock, stock, and barrel. Half-cocked. Flash in the pan. Fly off the handle. Even the insult ���gauche��� refers to left-handed men, deemed to be devilish for their unnatural way of fighting.

Because fighting was so much at the heart of society, it branched into every aspect of life. Learning the basic elements of swordsmanship is unbelievably helpful to the historical author ��� if only to let you know how easy it is to trip over your sword when walking up a flight of stairs. Such details are the lifeblood of our art, and are so often overlooked.

The HNS has offered me a wonderful chance to present some of this knowledge in two sessions this June, exploring different eras of swordfighting. For part of the time, we���ll be picking up swords and learning the basics, just as in the old fight schools and academies. For the rest of the time, I���ll be running through a history of swordplay in Europe, from the ancient Greeks through the Napoleonic era. I���ll talk about the evolution from cutting to thrusting, and how the Romans were far ahead of their time. And I���ll share stories and offer advice on how to write violence. Like every other element of our stories, it comes from character, and research.

In our business, nothing beats good reviews. With that in mind, here are a few kind endorsements from our colleagues who attended my last session in St. Petersburg:

C.W. Gortner: Having written historical novels where my characters wield blades, David���s workshop was invaluable and so much fun. I learned not only the proper way to hold a certain type of weapon, but got a real-life feel for the heft of it, the strain on my shoulder, the way I had to position myself to employ it. It made my writing come alive; I was always thinking afterwards as I wrote, how does this sword FEEL to the character?

Patricia Bracewell: I���m already signed up for the Broadsword Workshop with David Blixt in Denver. I attended David���s session in Florida and discovered that holding a sword and actually working with one are two very different things. Having listened to academic talks about swords I was somewhat familiar with the technical aspects of swordplay, but David���s workshop was a physical, hands on experience that was illuminating and great fun. Highly recommended.

Donna Russo Morin, author of The King���s Agent, a USA Book News Best Book of the year finalist and recipient of a starred review in Publishers Weekly: David Blixt���s Sword and weapon workshop was one of the highlights of my 2013 HNS Conference experience. With a combination of lecture and hands one time, it���s a fast-pace, fact-filled adventure. Whether writing battle scenes, duels or to simply identify which weapon belongs to which period, this workshop is essential. While I don���t write battles, I do write women in combative situations. Having the opportunity to wield these period weapons, learn basic moves, is not only fun but incredibly useful for almost all time periods. I highly recommend making this workshop part of the conference experience. It truly brings history alive!

Lisa Yarde: Very little topped the swordplay session during the Historical Novel Society conference in St. Petersburg. The very wonderful and personable David Blixt is an author, actor and as soon became obvious, David clearly loves historic weapons and historical fiction. He started off with an introduction to our enthusiastic audience on the history of swords and the mechanics of wielding a weapon. First, he talked about the parts of sword, then the evolution of swords over time. David also mentioned a neat tie between dance and fighting���

But what���s better for an author than training with the weapons our characters use? There were broadswords, longswords, rapiers, daggers and axes on hand. David showed us how to put weapons to effective use. For our characters, of course!

Alison McMahon: I went to the conference for the Historical Novel Society in 2013, which took place in St. Petersburg, Florida. A historical writer named David Blixt, who is also an actor and a fine specimen of gladiatorial humanity, taught a class on stage combat. I was instantly in love. With the fencing, that is. So when I got home, I signed up for a fencing class and took it for three months.

See you in Denver!

April 20, 2015

Musical

In a recent interview, one of the questions was something along the lines of, "What skill or ability do you wish you owned that you don't?"

That's easy. I wish I were musical.

I love music. I love singing. I am even told that I have a good voice. But I don't get music. I don't have that innate understanding of it that so many of my friends and colleagues have. I always feel like I'm on the outside, looking in. Or listening to a language where I recognize a few of the words, but not the sentence structure. I've taught myself to play instruments when I've had to for a show. But the knowledge doesn't stay. It's not in my body.

I can only compare it to swordplay. The first time I picked up a sword, I understood it on a visceral level. The moves fit my body, and while I am more suited to rapier and broadsword work than small sword, I instinctively understand that whole world. In precisely the way I don't understand music.

Which is why I'm in awe of my many musical friends. Because of theatre, I know so many talented musicians, singers, performers, and composers all. I love their work, and watch wistfully from the side, wishing I could speak the language.

April 17, 2015

Captive Colours Cover - A Cruel Tease

I'm getting a lot of heart-warming questions sent to me through the website and Facebook asking when CAPTIVE COLOURS (Star-Cross'd, Book 5) will be released.

Alas, I don't have an answer, because I haven't started it yet.

In fact, as I have at least four other books to finish before I do start it, I can't imagine diving back into Cesco's world until Fall 2016. Which would likely put CC late 2017 or early 2018.

I know. And I'm sorry.

To tide you over, I can offer up the cover. It's been on my Twitter page for two years, yet no one seems to have noticed. I designed all the covers in 2013, during a fit of productive procrastination.

So, without further fanfare, here's the cover to CAPTIVE COLOURS!

(Please note the change in crest, as it's significant. And if you're seeking a hint as to where Cesco and Detto go next, look at the paining. Or just Google 'Shakespeare ' and 'captive colors'...)

April 14, 2015

The Prince's Doom - Finalist for HF Award!

I've been away from my desk since yesterday, when I received word the THE PRINCE'S DOOM is one of three finalists for the M.M. Bennetts Award for Historical Fiction! This is my first chance to share the announcement I got in the mail:

The finalists for the M.M. Bennetts Award for Historical Fiction are:

This Old World by Steve Wiegenstein

The Prince's Doom by David Blixt

Lusitania REX by Greg Taylor

Needless to say, I'm beyond honored, and proud to be in such company. I'm also so touched to have the congratulations and support of so many other authors who were long-listed for this award. Their graciousness and good humor is why I so love the HF community.

The winner will be announced at the Historical Novel Society conference in Denver this June. I'll be there the day before, leading two lengthy workshops in swordplay. Honestly, winner or no, I'll be joyful to be with so many friends, celebrating and enjoying company. The problem is that with all the panels and events, there won't be enough time to socialize and play!

So thank you to the organizers of the award, and all the readers out there who make me feel so very lucky to do what I do. And see you in Denver!!!

April 8, 2015

No More Kings

I should explain why I so love Roman history. Yes, I'm attracted to the life of Julius Caesar above all others. I adore good retellings of Marius and Sulla and Gracchus and the rest. But to me, there is a single moment in time that fascinates me, and always will.

You see, among all the astonishing achievements of the Roman Empire, the one that most amazes me is the fact that it even existed.

After Romulus founded the city, murdered his brother, and conducted the rape of the Sabine women, Rome was just another city. It was ruled over by a minor king, who was followed by his son, and his son’s son. Despite the ties to Aeneas and the kings of Alba Longa and such, it was just another small monarchy, like any other through the ages.

Oddly enough, in a city born from rape, it was a rape that led to the most remarkable moment in Roman – and indeed, to me, all – history.

In 509 BC Rome was under the rule of its seventh king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The Tarquin’s son raped a distant kinswoman, Lucretia. She summoned four noblemen to call upon her, described the crime that had been committed, and then stabbed herself in the heart.

Here is how Shakespeare paints the scene:

Here with a sigh, as if her heart would break,

She throws forth Tarquin's name: 'He, he,' she says,

But more than 'he' her poor tongue could not speak;

Till after many accents and delays,

Untimely breathings, sick and short assays,

She utters this: 'He, he, fair lords, 'tis he,

That guides this hand to give this wound to me.'

Even here she sheathed in her harmless breast

A harmful knife, that thence her soul unsheath'd:

That blow did bail it from the deep unrest

Of that polluted prison where it breath'd:

Her contrite sighs unto the clouds bequeath'd

Her winged sprite, and through her wounds doth fly

Life's lasting date from cancell'd destiny.

One of the men present was named Lucius Junius Brutus. The nickname Brutus had been earned by his feigning of stupidity. But he had had to seem dull and brutish after his brother had been murdered on the order of the Tarqin, who had a nasty habit of murdering anyone who might rival him.

One of the men present was named Lucius Junius Brutus. The nickname Brutus had been earned by his feigning of stupidity. But he had had to seem dull and brutish after his brother had been murdered on the order of the Tarqin, who had a nasty habit of murdering anyone who might rival him.

According to Livy, Brutus tore the knife from the dead woman’s breast and ran into the streets, calling for the overthrow of the Tarquin, who also happened to be his uncle on his mother’s side. A notorious villain, the Tarquin lacked popular support, and thus both he and his son fled Rome as fast as their feet could carry them.

Again, the Shakespere:

When they had sworn to this advised doom,

They did conclude to bear dead Lucrece thence;

To show her bleeding body thorough Rome,

And so to publish Tarquin's foul offence:

Which being done with speedy diligence,

The Romans plausibly did give consent

To Tarquin's everlasting banishment.

This is the moment that amazes me. Because Brutus was related to the Tarquin, the people of Rome turned to him and began hailing him as the new king. At which moment Brutus said, “No. No more kings. Men can rule themselves.”

This is the basis on which our modern culture stands. And it’s this moment that’s so very revolutionary to me. True, other cultures had flirted with democracies, the notion wasn’t entirely new. But for a man being hailed as a king to turn away the crown was – and is – an astonishing act. An act of patriotism, of humility, of far-sightedness, of egalitarianism, and of honor. An act without precedent or peer.

Here, according to Livy, is a retelling of the oath that Brutus had the people of Rome swear:

Omnium primum avidum novae libertatis populum, ne postmodum flecti precibus aut donis regiis posset, iure iurando adegit neminem Romae passuros regnare.

First of all, by swearing an oath that they would suffer no man to rule Rome, it forced the people, desirous of a new liberty, not to be thereafter swayed by the entreaties or bribes of kings.

Brutus meant it. Among the events that followed was a conspiracy to restore the monarchy. Among the conspirators were Brutus’ two sons. He had them put to death. Though he wept bitterly at their executions, the notion of self-determination, of autonomy, of self-rule, were more important to him than his own life, or the lives of his family. It was a remarkable act of self-abnegation, of sacrificing for the greater good. (below is a painting byJacques Louis-David entitled The Lictors Bring To Brutus The Bodies Of His Sons).

Of all the amazing moments of Roman history, this is the one that stands out to me. Yes, the new government was far from perfect. An oligarchy of Senators is not much better than a king, as it’s still the wealthy above the poor, the entitled against the disenfranchised. But here we are, 2,500 years later, and this is the idea that still strikes a spark in men’s hearts, that kindles us to strive for something more that the random injustices of life. Men can rule themselves. For out of injustice rises a need for justice. Not just justice for the wronged, but for all.

That need for justice is more powerful than one’s property, family, or even one’s own life. Brutus died in battle against the Tarquin and his son, killing the son as he himself fell, thus preventing the family’s return to Rome.

This is the Brutus I wish we remembered. I think his act of courage is among the greatest in recorded history. However much I love Marius and Caesasr and Augustus and the rest of the more known Romans, to me the greatest act in the whole history of Rome was the founding of the Republic.

April 7, 2015

Senatus Populusque Romanum

Looking at the US government of late, I can’t help but think of Rome. It’s getting harder and harder to ignore the parallels, all coming faster and faster. It took the Romans nearly 500 years to get to where we are in just over 200.

Our most dire peril, as I see it, is the breakdown of the rule of Law. When our lawmakers dislike the laws that came before them, and decide to subvert them, the whole system is endangered.

The greatest gift the Romans gave us wasn’t aqueducts or amphitheatres, or even art. It was Law. The Roman court system was the envy of the world. Yes, there were miscarriages of justice, when a jury was bribed or a judge threw out an air-tight case. But even the very concept of standing courts was new to the world, as was a selected jury of your peers (rather than the unwieldy Greek version of a court, when the whole city came together to pass judgment. The Roman way didn’t shut down the society).

At the dawn of the Republic, when the first Brutus threw out the Tarquin and set up a new system of government, there were four inalienable rights of citizenship:

1 – A Roman had the right to vote. After the overthrowing of a tyrannical king, this was a huge guarantee, and vital.

2 – A Roman had the right to own property.

3- A Roman had the right to marry. This was later expanded to include all legal contracts – basically a Roman had the right to sign a written contract, or enter a verbal one, and expect it to be upheld.

4 – A Roman had the right to be whole in his person. Technically this means he could be beaten with a rod, but not whipped or cut – nothing that broke the skin. But it also had the effect that he had recourse at law for any injustice or indult given him – assault, etc. This also ended up guaranteeing a citizen the right to a trial before he was punished. The right to a fair trial is enormously important.

Having come from tyranny, these rights were precious, and ferociously defended, becoming the cornerstones of Roman law (and of course I should mention that these applied to Roman male citizens. Women eventually could own property, but the rest of their rights were not nearly as protected. A man could divorce a woman on a whim, whereas a woman needed a reason, and proof).

These foundations got expanded over time, as rights do. First conceived to protect Patricians (the “fathers” of the country), they then spread to cover all citizens, even Plebians. As more and more people got the citizenship, and therefore the vote, the ideal of Roman law was respected the world over. People from other countries would travel to Rome to get justice in a Roman court. A will lodged with the Vestal Virgins in Rome was considered so safe than many foreign kings placed their wills in those holy hands. Roman justice was seen to be swift, and by-and-large fair.

What eventually happened, though, was that the lawmakers started to not like the eroding of what they saw as their rights. There were too many “new men” coming up to join their ranks (some were even of Italian, not Roman, birth!) In response, lawmakers began rigging the elections, so that their votes counted more than those of ordinary people. Then they started holding themselves exempt from certain laws. Then they started passing laws to circumvent other laws. Then Cicero had five Roman citizens executed without a trial.

For all our talk of Caesar crossing the Rubicon, it was this undermining of the law that was the beginning of the end for the Republic. A country’s laws are only useful when they are seen as applying equally to all people, high or low.

I’m going to quote from my play Eve Of Ides, set the night before the assassination of Caesar:

CAESAR

The law is a breathing thing, Brutus. It cannot be static. When the Senate - a few hundred men of birth and wealth, making laws for people they despise - when they make laws that go against the wishes or interests of the people, they abrogate their authority.

BRUTUS

Is that how you see the Senate?

CAESAR

(laughing) I’ve been a member too long to see it as anything other than what it is - a collection of privileged fools who do nothing and obstruct everything. They’ll fight even the most basic, clear-headed notion because it was suggested by their political enemy. As if we were not all Romans. Picking absurd fights to protect some petty private interests, backing so deep into a political corner that my only viable solution is military. Lawmakers with a profound disdain for the law. That is how I see the Senate. Whereas you see it as you wish it to be - a just and wise body of men.

BRUTUS

The dreamer.

CAESAR

And the pragmatist.

This was a very reasonable view of the Senate in Caesar’s day. They routinely broke the law, violating their stated beliefs in order to protect their power and privileges, invoking Rome’s founders and traditions as a club to beat anyone who disagreed with them.

Does this sound at all familiar?

We must study Rome, not for simple love of history. Our own founders consciously based the government they created on the Roman system – two houses, a Senate and a House of Plebs; two consuls to run the executive branch; and a system of standing courts. With Rome as our model, it is imperative that we learn from Rome’s mistakes, not repeat them. Otherwise we’ll end up with too much power vested in the executive branch, a huge income disparity between the wealthy and the common man, and a military engaged in perpetual war.

Oh wait…

As I see it, we’re in the time of Gaius Gracchus. Gracchus, who tried to advocate for the rights of the common man above the elite. When he was opposed by a faction of backward-looking zealots calling themselves the Boni (the “Good Men”), who pulled the same parliamentary tricks as the Tea Party this last fortnight, Grachus said, “A tribune who diminishes the privileges of the people ceases to be a tribune of the people.” I couldn’t agree more.

Being in the time of Gracchus means we’re not doomed yet. But if Rome is a reliable roadmap, in about 100 years we’re destined for our own Nero, our own Galba, Otho, Vitellius, our own Year of the Four Emperors. That year, 69 AD, was a nightmare of unconstitutionality. But by then, the constitution of Rome was so badly trampled that it was virtually useless.

When law-makers live outside the law, the law ceases to have value. As Truman Capote said, “The problem with living outside the law is that you no longer have the protection of it.”

By the bye, I don’t have a soapbox in The Four Emperors. It’s just my attempt to tell an excellent and exciting story, a story worth telling. But history is more than a window into the past. History is a mirror, a window into ourselves. As I said in an interview last week, “We forget our history. That’s what literature can do – remind us not of where we are, but how we got here.”

Senatus Populaesque Romanum: “The Senate and People of Rome.” We forget the People at our peril. The same is true of history.

I’ll close with a lengthy exchange from the end of Act One of Eve Of Ides:

CAESAR

You of all men might understand. Seven civil wars in my lifetime. Seven. Add to that proscriptions, purges, and outright murder, and what do you have? Chaos. Rome is foundering. You must see that. Our customs and beliefs are dashing themselves against the facts of our times. The ideals of our founders are either ill-equipped for modern man, or else ill-served by him. The poor are frightened by the change, and they cling to the three staples of their lives - their gods, their games, and their bread. The Second and Third Classes want to join the First Class while the First Class wants to protect its exclusivity. We with the birth, the money, and the will to govern are expected - needed - to provide for the lesser among us. Else the Republic will fall.

BRUTUS

The Republic is eternal.

CAESAR

Nothing is eternal. Not even the gods. Without a firm hand, we will return to Pandora’s world - a world of chaos. It’s almost as though someone has defied the gods and shouted out Roma’s secret name into the open air, heralding our destruction.

BRUTUS

Is that the choice? Caesar, or chaos?

CAESAR

Not a palatable choice, I’ll confess. But you must see that a dictator is better than destruction.

BRUTUS

I’m not so sure. We cannot have a king - or a Caesar - and still be the people our forefathers envisioned.

CAESAR

But they couldn’t envision the state in which we find ourselves today! We’re no longer that tiny colony on the seven hills, desperate to survive the wolves. We have interests in foreign lands, far-flung peoples and places. Our wealth is great, our prestige greater, our enemies greater still. The sign-posts our ancestors planted should guide us to who we will become, not bind us to who we were. An example - from the time of our founding until a generation ago, the poor had no stake in the society. The army was filled with men of means - men with property have property to defend. But that changed when Marius saw Rome’s need for soldiers - an honest need, with the Germans coming for us like an avalanche. Lacking men, he drafted the poor. Practical. But fifty years on, what do we have? Professional soldiers coming home to find themselves rejoining the poor, wondering why they were called to fight for their country. Was it to join the Head Count and starve once discharged? Military training married to starvation births revolution. And not one of our civil civil wars, with Senators battling Senators. This will be a genuine uprising, with the people overthrowing the lot of us. As a consequence, Rome today needs wars, constant wars, foreign wars, until we are prosperous and equitable here at home. Without wars abroad, we sow the seeds of our own destruction here at home.

BRUTUS

Perpetual warfare? That’s a terrible solution!

CAESAR

Offer an alternative. Should we tax businesses? The poor? Women? That is the choice - wars of conquest, or taxation. War is both popular and profitable. We can try to replace it with arena games, but nothing matches the patriotic fervor of war, nor its ability to produce funds.

BRUTUS

We should just return to the old ways. Leave the rest of the world to fight each other. Remain above it.

CAESAR

We tried! We tried, but they came for us anyway! Carthage, Pontus, the Germans - we fought them and fought them until we saw the only way to keep them at bay was to conquer them. I am not saying I approve, Brutus. I’m saying this is where we are.

BRUTUS

Are we a nation of brigands, then? Foreign wars are theft writ large.

CAESAR

Whereas civil wars are not about wealth or land. They’re about our idea of ourselves. Most men are sadly incapable of defining themselves by what they are, so they rely on what they are not. Being Roman has to mean more than merely not being Greek or Aegyptian. If we cannot have a foreign foe to define us, we will create one within our own ranks. And the sides will forever line up between youth and learning on the one hand and tradition and dogged ignorance on the other. One side sees the need for change, while the other sees the passing of the old ways and resists.

BRUTUS

No illusion to which side you favor in that struggle.

CAESAR

There is value to our history, but it cannot dictate our future.

BRUTUS

Says the Dictator.

CAESAR

Says Caesar.

March 24, 2015

Fixing Education in America

I've been listening to the debate on education. A lot of focus seems to be on teacher accountability, on parent choice, and on testing.

There doesn't seem to be a lot of focus on the students.

Because if you focus on the students, fixing education in America is suddenly easy. It's ridiculous easy. It's a three step process.

Step 1: Hire more teachers.

We've past the point of capacity on classrooms. Now teachers can't actually teach. Their job is crowd control. Once you've passed 25 students in a classroom, there aren't enough minutes in a day to give kids the individual attention that will let them succeed. Instead teachers are all about group dynamics, and always end up dealing with the loudest kids, the troubled kids, the unruly kids, just to make the class tolerable. Which means the shy kids, the quiet kids, the happy kids - they don't get to interact with their teacher.

Instead, teachers give them all busywork. Just nonsense, hours and hours of nonsense. They aren't teaching, they're just reacting to 35 children in a room with no help or relief. The job of teaching is hard when you've got 15. It gets exponentially harder at 25. Past 30, you're just hoping no one bites anyone else. And this is when you're in a school where all the kids have three square meals a day.

Students don't need worksheets. They don't, in elementary school, need three hours of homework. What does that do, save make them hate school? A rule of thumb is ten minutes of homework per grade. One of my son's classmates just transferred in from a school that gave more than two hours of worksheet homework a night. In second grade. Now he has less than half an hour homework each week. And suddenly he's not stressed about school. He doesn't have nightmares about it. He likes his classes. He likes learning.

Students don't need worksheets. Students need individual attention. They need to be recognized as people, unique people with individual needs and a distinct personality. But when a teacher is teaching to a huge mass of students, only the neediest or most vocal students will receive that attention. It's like a MASH unit. Everything is triaged, and there isn't time to help everyone.

So we need to reduce class size by hiring more teachers.

Step 2: Teach more subjects.

Not every kid learns the same way. Some kids will respond better to reading something than hearing it. Some will experience the reverse. Some will get it automatically, some will struggle. Kids need as many doors into learning as can be opened for them. And that's where diverse subjects come in. Not just the 3 Rs, but Music, Art, and Drama. These are not extras. They are tools for teaching.

Personally, I think history is taught wrong. It's not dates. It's stories. Tell the stories, make it about the people and their ideas, their struggles and their lives. But that's my door into history. Someone else won't respond to that, they'll want the dates. So you need to have it all. Cutting subjects is cutting core education, not "extracurricular" activities. They're all curricular. They are all a part of learning.

So is recess. Kids need time to let their brains relax. There's only about 90 minutes of doing one thing before they get squirrelly and start to need diversion. And children need physical activity, and play. They learn social interaction through play, and they also apply what they've learned in the classroom in their play. So let them play!!!

Now we come to Step 3: Stop thinking education should be a for-profit enterprise.

This is the new one, and it's wrecking modern education. Corporations have seen all the money going into education and have decided they want a piece of that. But is the goal to put that money into education, or to make a profit?

Here's a scary fact - the private sector doesn't always do it better. Remember when soldiers got electrocuted in the field because the government outsourced the building of their barracks? Did you know that Medicare has a less than 3% staff wage rate - that is, less than 3% of the money spent on Medicare goes to pay the wages of those that run it. The rest goes directly to healthcare. That's astonishing, and minuscule compared to what private insurers spend on admin. Because there are conflicting goals. Provide healthcare. Turn a profit. Those two goals will always be in conflict, and greed will win.

The same is true with schools. Is the goal educating the next generation of Americans? Or is it turning a profit? Because once the latter becomes part of the equation, we suddenly have all sorts of corners being cut. In Chicago they've privatized janitorial services, hiring it out to the lowest bidder. It is more expensive than it was when done in-house AND the schools are suddenly filthy - rats and bedbugs are being reported all over the place.

If student-teacher ratio is an historic measure of quality, what does it say when we pile 35-40 students into a room - one without proper climate maintenance, because they've outsourced that too. The argument is competition is good. The results don't agree. Testing for charter schools is marginally better than public ones, and that difference is easy to explain - the public schools are being drained of that money, and charter schools get to choose their student population. Imagine if all that money was going to hiring more teachers, and giving the students more options.

Some things shouldn't be exploited for money. I think healthcare and utilities should be non-profit, but those ships have sailed. There's still time to save education, though.

These three solutions don't even touch a couple other problems with schools today - lack of student accountability and lack of parental involvement. To the first, remember when getting a B was good grade? When a C student was average? When earning an A meant a huge achievement? And to the second, parents don't have the time today to be fully engaged in their children's education. Income inequality means they're working all the time. Which is why they rely on teachers to make their children perform - and blame the teachers if the students are failing. Teachers are not to blame for a kid's failure. That's called personal responsibility, and it's the parents' job to teach that one.

Oh, and for the love of God, knock it off with the testing. If they spend more time testing than actually learning, what kind of education are they getting?

Focus on the students. So simple, it's obvious to a child. Now if only we could convince the adults...

March 22, 2015

Fighting The Wrong Fight

It’s headline news, in my world at least, that Los Angeles members of Actor’s Equity will be picketing the offices of their own union this week. While I see their point most acutely, I gotta say, I don’t like the big picture of this narrative.

Labor unions were once the backbone of American prosperity. From the 1930s to the 1980s, they created a voice for the working class, and consequently built the middle class of this country. We have the concepts of the 8-hour workday, weekends, and overtime thanks to unions. It’s a very American idea – E Pluribus Unam. “Out of many, one.”

But unions are the demons of modern day politics. Want to score political points? Bash the unions. Republicans, want to hurt the other side’s fundraising? Break a union. Democrats, want to show your independence? Slam a union. Not police or firefighters, but man those teachers unions are good pickings.

Statistically, it’s a race towards the bottom. The lowest wage states in this country are the so-called “right to work” states, where membership to a union is voluntary. Without the backing of a healthy and vocal majority of the people it represents, unions cannot effectively negotiate for better wages and better conditions for everyone.

Unions aren’t blameless. There are messaging problems, to be sure. And so often unions try to cut deals in order to be seen to be effective, deals that sell their membership short. Or worse, they simply fight the wrong fights.

That’s what this thing in LA strikes me as. The wrong fight.

There are plenty of great pieces giving the narrative over the 99-seat theatre fight, and I won’t get into it in depth. AEA had a rule in place for the last couple decades that allowed its members to perform for less-than-standard wages and no benefits in certain theatres. They are now trying to undo that deal.

But the 99-seat theatres aren’t the problem.

There isn’t enough money in theatre. That’s the problem.

The small theatres – with complete truthfulness – plead poverty. Paying even minimum wage for actors through rehearsal and performance would wreck them. It’s mathematics. With a 99-seat house, there is no way to bring in enough ticket revenue to sustain more than a two or three person show, let alone a season. Not unless tickets are $100 each.

The union should not be trying to force wages upon theatres that are clearly unsustainable. The union should instead be fighting to help make theatre funding more robust. Why isn’t the narrative about how the US spends less on culture than any other industrialized nation on earth? Why are we not fighting for local, state, and government grants to support theatre, walking arm in arm with the theatre producers themselves?

Theatre is a tradition in America. Traveling wagons would roll from town to town, putting up shows. The most famous theatrical event in American life happened, of course, in Ford’s Theatre. But we tend to ignore the fact that Lincoln was a theatre-goer. Just as it’s easy to forget that during the Great Depression the WPA put up shows and built theatres all across America. FDR understood that it isn’t enough to feed a man’s stomach, you had to feed his soul. Which is how we got the Federal Theatre Project, specifically created to both employ artists and entertain and inform the people.

For anyone arguing theatre is for old rich white people, I disagree. Theatre has become for old rich white people as funding has been choked off. The economics of the last 30 years have created a circumstance where only old rich white people can afford to attend theatre, forcing theatres to cater to that audience’s expectations.

But that’s not the history of theatre. Theatre is vital, it is where unheard voices speak. In countries where monopolies or the state control the media, theatre has been the place where truth can be spoken. Theatres are laboratories of narrative, of how a society finds out what it’s trying to say. In times of both tumult and prosperity, theatre is a magnet for the young to express themselves.

The best part of theatre is that it’s local. Just like sporting events or concerts, theatre is a shared experience. In a world more and more separated by technology, human interaction is rare, and valuable. And study after study shows that a theatre enriches the economics of the city or neighborhood where it exists. People go out for dinner beforehand, maybe shop a little while they wait for curtain time. Then they go out afterwards to discuss over drinks.

But this is money the theatre itself never sees. Local businesses should be fighting to get a theatre in their neighborhood. And the city should be helping build that theatre, enriching the community and employing the professional actors it hires.

Some cities recognize this. In Chicago, theatres like Looking Glass and Chicago Shakespeare have amazing deals with the city for their physical plant – because the city knows that these places are great tourist destinations and do more for the image and economics of the city than they cost. It is a terrific return on the investment.

But the Arts are a great place to cut funds. No one NEEDS theatre to survive. Nor music. Nor painting. The first thing that happened when the new governor of Illinois took office was that all the theatres received a letter saying that all state funding was frozen. If they had been promised money, they might get it someday. But as of now, all arts spending was halted. Basically ensuring some companies fold, thereby reducing a key component to the economy, one that gives back between five and ten times what it takes.

This is where the union should be working hand-in-glove with the theatres and producers. It should be making the argument in town halls, in state capitols, and in Congress, voicing the benefit of having professional actors and stage managers, raising the quality of theatre in America.

The American psyche can understand the difference between amateur, college, and professional sports. It should have the same understanding of community, college, and professional theatre. There are lots of talented people who don’t pursue careers in the theatre, are content to make it their hobby. It is absolutely no reflection on their talent. But it feeds into the narrative that “anyone can do it”.

For those who have made it their career, who have survived the draft and gotten the jersey, there should be an understanding of the difference. That’s what the union should be promoting, not internecine fights, but the argument of why professional theatre matters. And fighting for more professional theatres for its members to perform in.

For us union members, we don’t need convincing. We know why we get paid before the weekend of the show, because back in the day producers would run off with the box office take during the final performance. We know that we deserve our ten-minute breaks every 90 minutes. We like knowing how many hours we can be worked in a week. We like there being rules for how we are treated, and that there is a member of our union we can turn to if a director or producer crosses a line. These are all things the union does for us, and we know and appreciate them.

But every time the union ups the number of weeks an actor must have to get healthcare, or when an actor tries to work with a company only to be denied a special appearance contract, or all the other ways the union limits the chances for actors to act, it feels like the union is not for us.

The way this current fight looks is that the union is trying to stop its members from performing at the LA theatres they’ve called home for over 20 years. Fewer opportunities for them to act means more of them will have to find other work. But the union doesn’t care about the work its members do when they’re not acting. Just so long as they pay their dues. And AEA's tone has been terrible, both disingenuous and dictatorial. This is the tension between the union and its members.

For this fight, AEA has jumped on a very popular narrative – the minimum wage. I agree, every actor should at least make the minimum wage. But then I ask, where does that money come from? That’s the part the union cannot answer. Because, once again, they’re fighting the wrong fight, against the wrong enemy. The producers aren’t the enemy.

Apathy about theatre is the enemy.

Lack of funding is the enemy.

National income inequality is the enemy.

The image of union members picketing their own offices will make for great television. Famous faces on the picket lines will certainly draw attention to the fight. But it will, as is the nature of our discourse today, be without nuance. It won’t have the complexity of union reciprocity, of starvation wages for theatre staff, or decades of cuts for NEA funding.

It will demonstrate just two things: Unions are evil, and actors are unprofessional.

Neither narrative helps.

E Pluribus Unam.

(For more excellent cogitation on the issue, drop by Chris Walsh's page. He's got the goods. And links to several more stories, too)

(A fun link – I went back to look up some WPA facts and found this 1938 transcript of Hallie Flanagan, FDR’s head of the Federal Theatre Project, testifying before HUAC – the House Committee on Un-American Activities – about the nature of her program. It’s hilarious – especially when they ask if Christopher Marlowe was a communist).