David Blixt's Blog, page 17

February 5, 2013

Negative Space, or What Will Won't Do

It’s dangerous,

playing the expectations game. You rewrite Romeo

& Juliet, you’d best bring something new to the table. You write

about the fall of Jerusalem, there had better be something surprising and

uplifting in that awful story. And if you write a novel about William

Shakespeare, you’d best hope that you don’t get crushed by the weight of

expectations. Especially your own.

That was the

That was the

danger I was facing as I sat down to write Her

Majesty’s Will. Even though I knew it would be light-hearted and joyful,

a romp of a spy/buddy/comedy, I was still casting William Shakespeare as my

lead character. William Shakespeare! The man who invented one of every ten

words we use. The man who created more common phrases than we can count. The

man whose only rival in terms of influence is the Bible. William Shakespeare!

That’s the problem,

you see. I love Shakespeare – or rather, I love his plays. I’ve been performing

them professionally for over half my life now. I met my wife doing Shakespeare.

Last summer our six year-old son joined me onstage to do Shakespeare. Of the 36

accepted titles that bear his name, I’ve played roles in 19, so I’m just about

halfway through the canon. Through the plays, I think I’ve got a vague sense of

the man: his values, his mistrusts, his instincts, his loves, his hates, his

sense of humor, his sense of drama.

But almost all

of it is negative space. We don’t have anything even remotely resembling an autobiography,

only lines here and there that we can speculate about – Hamlet’s instructions

to the actors, Jacques’ cynical musings on life, Richard II’s thoughts on

England itself. Any of those might be the playwright’s true voice. Or they

might not. Then there are sonnets, which we might take as his own voice, if we

did not know that many of them were written on commission for other people.

Taken together,

that’s not a lot to go on. So when it came time to craft a tale with young Will

Shakespeare at the center, I had to infer a lot. Fortunately, there are themes

that emerge in his plays time and again, snippets and beats and moments that,

taken together, present a picture.

So what do I see

in Shakespeare’s plays?

– I see mistrust

of power and those who crave it. From Henry IV to Richard III, from Lear to

Macbeth, from Caesar to Antony to Octavian, Shakespeare shows how ambition is

often a snake swallowing its own tail, how desire for power leads men to evil.

How power itself is unfulfilling, yet absolute power corrupts absolutely:

BRUTUS: But 'tis a common proof

That lowliness is young ambition's ladder,

Whereto the climber-upward turns his face;

But when he once attains the utmost round,

He then unto the ladder turns his back,

Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees

By which he did ascend.

That formula is

as true for the Church and for Government as it is for Mankind. Power is

dangerous, as is ambition. Yet he resolutely holds out hope that man can

transcend this evil. Perhaps my favorite line from Macbeth belongs to Malcolm: Angels

are bright still, though the brightest fell.

Conclusion: Shakespeare mistrusts authority – does that mean

he’s seen the evil of authority up close?

– I see a

longing for justice. It’s in the comeuppance he gives all his evil-doers. From

Richard’s dream to Edmund’s recantation to Iago’s silence to Macbeth’s

sleep-deprived madness, the evils men do return to them. It’s almost a sense of

karma, though if that were the case, then there would not be the harm to the

innocents that also appears – Macduff’s children deserved no karmic suffering,

and poor Cinna the Poet did nothing wrong. No, Shakespeare makes it clear that

there is evil in the world, but also that God or Fate or the nature of evil

itself brings evil back to evil. Blood will have blood, as they say.

This is as true

for the Comedies as for the Tragedies. Malvolio gets a cosmic comeuppance as

he’s made the fool of by those he sought to overmaster. Yet his tormentors go

too far, and he swears he will have his revenge. At that moment, I agree with

him that they deserve it. His crime did not warrant such treatment, and shows

the danger of trying to effect justice outside the law. Shakespeare is no fan

of vigilantism, yet he understands it. And he detests arbitrary justice, as

seen in Justice Shallow in Merry Wives.

Conclusion: Shakespeare

longs for justice – because he has been wronged?

– I see his need

to side with the misunderstood. So many of Shakespeare’s best characters are

outsiders. Othello, Iago, Shylock, Aaron, Edmund, the Bastard Arthur, Richard

(thanks to his deformity) – these men are, every one, outsiders. Yes, the

majority are villains, because that’s what the audience expected, and because

villains are the ones who make a story move. But to a one, Shakespeare gives us

some of the most amazing, heartfelt defenses for who they are:

SHYLOCK: If you prick us, do we

not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not

laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you

wrong us, shall we not

revenge?

EDMUND: Why bastard? wherefore

base?

When my dimensions are as well

compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape

as true,

As honest madam's issue? Why

brand they us

With base? with baseness?

bastardy? base, base?

RICHARD: I, that am curtail'd of

this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling

nature,

Deformed, unfinish'd, sent before

my time

Into this breathing world, scarce

half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark

at me as I halt by them.

That is to say

nothing of the women, outsiders in their own right. The life he gives to

Rosalind, Viola, Kate, and Merchant’s Portia is truly astonishing. They are, in

fact, the true leads of their plays, challenging gender roles either by being

shrewish and assertive, or else by donning man’s attire and becoming men

themselves, always proving better and wiser men than the actual men around

them.

Conclusion: Shakespeare

embraces the outsider – because he is one?

– I see him

challenging his audience’s perceptions. There are obvious examples, such as

writing a Comedy and then killing everyone off (Romeo

& Juliet) or rewriting a popular play like The Taming Of A Shrew to make the female the one who “wins”

at the end (and in his version, she’s not whipped and beaten). But the one

that’s been most on my mind lately is the startling nature of his play Julius Caesar. Until 1599, Brutus was

firmly denounced as one of the great betrayers, being eternally chewed by

Lucifer in Hell, second only to Judas in terms of his crime. Shakespeare does

the unimaginable and recasts Brutus as the hero, the man who does a terrible thing

for an excellent reason, raising all sorts of moral questions, while at the

same time redefining Brutus for all time. It may not seem like much to us, but

it was a revolutionary act.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare sees the world differently from other men.

– I see the law

of unintended consequences. Nothing in Shakespeare goes according to plan. From

the death of Caesar failing to restore the Roman Republic to the secret

marriage of Romeo and Juliet failing to solve the feud (well, it does, but not

in the way the Friar intended). Tricking Benedick to fall in love with Beatrice

leads to Benedick challenging one of the tricksters to a duel. Shylock

demanding his pound of flesh ends with him impoverished and a forced convert to

Christianity. Nothing – nothing –

goes according to the plan of men.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare knew that life was unpredictable, and one must think quickly to

survive.

Above all, I see

Shakespeare’s love for the common man – the peons, the rabble, the rank and

file. Oh, as a group he disdains them – he rails at mobs at the top of Caesar, and during Mark Antony’s speech

proves how short their memories are, how quickly they can be swayed. But individually

he loves them. He certainly caters to them, pandering to their tastes with low

humor and bawdy jokes. But he also finds more good in their raw honesty than in

all the upright nobility. It is the rough, the rude, the boisterous that he

admires. Oh, they have faults, but he loves their faults along with their

virtues. Drunkenness, lewdness, cowardice, cheating, lying – these are all

accepted purely as clever means to survive in the world. He gives his greatest

wit to clowns and fools, and makes drunkards the most joyful of his creations.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare accepts and loves low men – because he came from their ranks.

So as I thought

about my Shakespeare – not the real one, but the one being created by my pen – this

is the man I saw. A fellow of common birth and uncommon thoughts. A man who

understood the vagaries of life and yet longed for justice and order. A man who

has played the villain for the best of reasons. A man quick on his feet. A man

mistrustful of authority. A man who craves the approval of his peers, even when

his nature renders him peerless. A man who has always felt on the outside,

misunderstood, different, alone.

Even before I

cracked Stephen Greenblatt’s wonderful Will

In The World, which gave me incredible historical details for

Shakespeare’s origins and contemporaries, the man himself was shaping from the

negative space created by his plays into a positive and (thankfully) very human

character.

I’ve always

maintained that Her Majesty’s Will

isn’t serious, and it’s not. Will Shakespeare and Kit Marlowe running around as

spies for Walsingham, working for the Queen? Ridiculous! I certainly wasn’t

aiming to write a biography or some serious piece of literature. This is farce.

I am the first to acknowledge that.

But just as

Shakespeare gave his best bits of wisdom to his fools and clowns, I hope that,

through my own clowning, I’ve been able to imbue my Shakespeare with something

close to Truth. If this is not who the real Shakespeare was, this is perhaps

who he should have been. A man not

dragged down by the weight of my expectations, but rather raised up by his own.

February 2, 2013

On The Shoulders Of Giants

“Writing is easy. You only need to stare

at a piece of blank paper until your forehead bleeds.” – Douglas Adams

When I set out

to write “Her Majesty’s Will,” I was scared. Why? Because I wasn’t going to be able

to rely on my usual bag of tricks. I was setting out to do something I’d never tried

before. I was going to write a Comedy.

Now technically, Comedy doesn’t mean funny. In

the loosest sense, it means it has a happy ending – Shakespeare always ends his

Comedies with a marriage, sometimes accompanied by a song. Aristotle tells us

that Tragedy is about grand things and noble people, while Comedy is about

small things and ignoble people (Mel Brooks says that Comedy is about Tragic

things happening to other people).

But today if you

say you’re writing a Comedy, everyone expects to laugh. And when I first came

up with the notion of filling in the gap of Shakespeare’s ‘Lost Years’ by

making him a hapless spy, I knew I couldn’t treat it as one of my ‘serious’

novels. It was a silly idea, and had acknowledge that fact. It had to be funny.

The problem with

that is, simply, I’m not funny. I’m in theatre, so I know some insanely

talented funny people, and that’s not me. I have a very dry sense of humor, and

I loathe most sit-coms and any movie that relies on embarrassment for a laugh.

I like (some) buddy comedies, (most) screwball comedies, and anything full of wit

(hello, Douglas Adams and Eddie Izzard) or ribald badinage (hello, Shakespeare

and Aristophanes).

So when it came

time to be funny, I went to the well of my favorite humorists to figure out the

elements of what I like in a Comedy.

Not to learn.

To steal.

“Mediocre writers borrow. Great writers

steal.” – T. S. Eliot

Naturally, any

Comedy about William Shakespeare has to employ Shakespeare’s own comedic devices

– cross-dressing, mistaken identities, disguises, musicians, mis-timings,

clowns, bawds, and big reveals (if I could have added a ship-wreck, I would

have!). The Bard thus gave me a mental check-list to cover. A good start. Besides,

Shakespeare stole the plot for every story he ever wrote. So he couldn’t judge

me for thieving.

That raised the

issue of a plot. But in perfect truth, I didn’t really care about the plot. Not

this time. I simply looked at a list of events during the years before

Shakespeare appeared in London, and right there was the Babington Plot.

Elizabeth, Mary, Walsingham, Catholics, spies, and a beer barrel? Sold!

I also knew

right off the bat that this was a buddy comedy, teaming Will Shakespeare with

the wily, mercurial Kit Marlowe (who really was a spy). At once I recalled my

favorite books in that vein, the Myth Adventures series by Robert Asprin. I

actually knew Bob back when I was a kid, and to this day I love the adventures

of Aahz and Skeeve.

Of course, those

Of course, those

books are Bob’s own homage to the Road Movies of Hope and Crosby. So the book

became a Road Movie. That gave me the framework. Watching those films, I love

how Hope and Crosby are always undermining the other, and through their

self-interest they create their own perils. Every decision they make to save

themselves only gets them in deeper. In their self-assurance and arrogance, they

were their own worst enemies.

Where had I seen

that before?

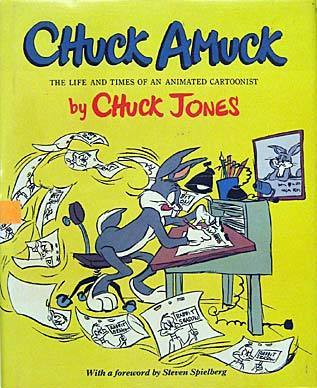

“Comedy is unusual people in real

situations; farce is real people in unusual situations.” – C. M. Jones

Before Shakespeare, before Aristotle, before

Bob Asprin, Eddie Izzard, or Douglas Adams, I learned Comedy from one source,

and one source only: Charles M. Jones.

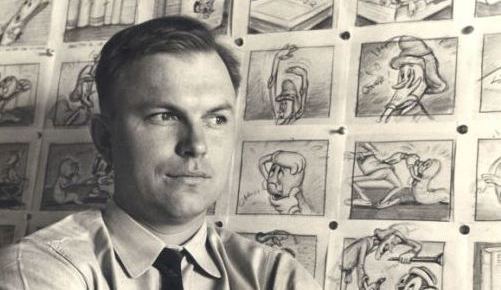

It mortifies me to think that there might be

people alive in the world who do not know his name. But all one has to do is

start singing “Kill the Wabbit, Kill the Wabbit!” and everyone smiles and nods.

Yeah. That’s him. One of Bugs Bunny’s creators, the inventor of Road Runner,

Coyote, and Pepe le Pew, and the re-inventor of Daffy Duck. The man who gave

the Grinch his Grinchy smile. That’s Chuck Jones.

Chuck had his

own inspirations – Charlie Chaplin, H. L. Mencken, and Mark Twain. You can see

his comic timing and commentary on humanity come from them. In marvelous,

6-minute snippets, he distilled them into pure comedic gold. I’ve watched all of Chuck’s cartoons, from his early attempts to be

as cute as Disney through him slowly finding his voice to the height of his

career, when he crafted the best comedic moments of the 20th Century.

Because Chuck understood that comedic heroes never go looking for trouble, just

react when it arrives. Moreover, he created the best buddy comedy team of all

time in his pairing of Bugs and Daffy. The one is who we want to be, and the

other is who we are. Or as film teacher Richard Thompson once said, “Bugs

talks, and Daffy talks too much.”

Why hello, Will. Hello there, Kit.

“Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words.” – M. Twain

So – theme, tricks, frame, ‘plot,’ all

complete. All that was lacking was the Voice.

More than any other kind of story, Comedy has a

voice. On stage or in film, it’s often a literal voice, with a character

looking at or talking directly to the audience. But sometimes it’s the frame of

the shot, the juxtaposition of lines and action, or simply lingering an extra

beat to watch a comedian react. Chuck called it a Motivated Camera, and the

motivation is sharing something with the audience. Like laughter itself, Comedy

is best when it’s shared.

It’s hard to pull off. But in novels, it

becomes even trickier. The true master of this was Douglas Adams, who never

hesitated to use his narrative voice to be absurd and wonderful. Knowing that I

am certainly no Douglas Adams, I found myself thinking, of all people, of

Charles Dickens. Because while he was never absurd, he also didn’t stint from

commenting upon his characters: “Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the

grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching,

covetous old sinner!” Imagine the shock and sneers if some modern author

described a character in such a way. But it’s a tradition stretching proudly

back from Homer to story-tellers around campfires to minstrels and bards – the

active voice of the narrator. Also wonderfully used in the Goofy cartoons of

the early 1940s (watch “How To Ski”), as well as top and bottom of Chuck’s

forgotten classic “Fin’n Catty.” So I decided to employ that same voice – arch,

but never winking, and never afraid to comment on the action or the people.

Thus I was ready. Armed with the best elements

of my favorite Comedies, I jumped in.

Then stopped.

Because it wasn’t funny.

“The secret to humor is surprise.” Aristotle

I was daunted. Oh, the tone was right, and the

action was fine. But there was one element that I had entirely neglected, a key

ingredient, the je ne sais quoi, an

X-factor that kept it from singing, kept it from leaping off the page, kept it

from making me want to keep writing.

So I put the story in a drawer for a couple

years. I knew what I wanted, but I decided I just wasn’t funny enough to pull

it off. Maybe I’d grow funnier with age – though it hadn’t happened so far.

There’s a great chapter in Natalie Goldberg’s “Wild

There’s a great chapter in Natalie Goldberg’s “Wild

Mind” where she talks about the perils of wanting something too much. That’s

happened to me in lots of auditions. I want it too badly, so I blow the

audition. Whereas if I’m relaxed, if I’m myself, that’s when I tend to get

cast. It’s a truth I’ve known since I was 19, but like all truths in my life,

it’s one I have to keep relearning.

Here’s another truth, one I also forget to my

peril – the answer is always in the research. That’s where inspiration lies.

In the case of this novel, the answer was in

Stephen Greenblatt’s marvelous “Will In The World,” a book not strictly about

Shakespeare himself, but about the world he inhabited, extrapolating out small

details from what little we know and putting them all firmly in context. It is

a treasure on its own, but to me, it gave me the thing I’d been lacking, the

true key to crafting the story I wanted.

I had forgotten that, more than anything else,

all great Comedy has to have heart.

“Comedy is defiance. It’s a snort of contempt in the face of fear

and anxiety. And it’s the laughter that allows hope to creep back on the

inhale.” – Will Durst

A comic hero rises from pathos, from a desire

to be understood. He also owns strong indignation at injustice. It was

something Chuck knew, and wrote about frequently: “Like all heroes and

heroines, Bugs Bunny grew strong when strong villains began confronting him…

Bugs never engages with an opponent without reason. He is a rebel with a cause.”

In Greenblatt’s book, I saw glimpses of a

In Greenblatt’s book, I saw glimpses of a

potential comic hero in Will: a brilliant, frustrated, eager, disappointed,

gullible, cynical, empathetic, cutting, witty, and humble young man. I know

Shakespeare from his plays. But by putting him firmly in his world, he became

more human. He became the mass of contradictions that we all are, that Comedy

seeks to exploit. He became that rebel with a cause. With something to say.

Then there’s this, too: “Bugs emerges into the

battle zone as a sort of cross between Groucho Marx, Dorothy Parker, James

Bond, and Errol Flynn. Bugs loves the thrill of the chase. Once engaged, he is

the most enthusiastic of participants: saucy, impudent, and very quick with

words in circumstances that would confound most of us.” Ah, yes. That’s my man.

And Kit? Again Chuck writes: “Bugs succeeds

And Kit? Again Chuck writes: “Bugs succeeds

because he is successful, but Daffy needs great determination in the fight to

win the recognition he knows he deserves… A public loss of dignity will all but

destroy him. The more you know Daffy, the better you like him, because you are

going to recognize yourself.”

The secret to Comedy is humanity. If Tragedy is

about rising above our frailties and foibles to be our best selves, Comedy

exploits those frailties and foibles, but never maliciously. Lovingly. With

empathy.

“Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up,

but a comedy in long-shot.”

– Charlie Chaplin

So when I finally sat down to write Her

Majesty’s Will, it practically wrote itself. Standing on the shoulders of

comedic giants – Twain, Mencken, Chaplin, Hope and Crosby, Adams, Asprin,

Jones, and Shakespeare himself – they all reminded me that Comedy is all about

us getting a happy ending we probably don’t deserve. Will gets better than he

deserves in this novel. Kit absolutely gets better than he deserves. And this

book turned out far better than I ever deserved.

The best part was that I was smiling the whole

time I wrote it.

(One last Chuck quote: “The rules are simple. Take your work, but never yourself, seriously.”

Amen, brother.)

January 31, 2013

Verona - Travel and History

There are two terrific options when it comes to reliving history. You can either read about certain eras or actually walk in the footsteps of history's greatest figures. Thanks to David Blixt's thrilling historical fiction The Master of Verona you can actually do both.

It makes sense that an acclaimed Shakespearean actor of Mr. Blixt's caliber would set his novel in two of Shakespeare's most famous destinations. Verona was the setting for the tragic lovers Romeo & Juliet while Padua was the local for the perennially topical Taming of the Shrew. However, it is famed Italian poet Dante and his sons that play the central figures in The Master of Verona. Now, you can use this exciting novel as a guide to plan out the quintessential Italian journey through two of its most beloved cities.

A Little History Lesson

Verona and Padua are both situated in the same Northern Italy region and are separated by just twenty miles. It's conceivable to chose one of these cities as your Italian "home base" then plan out day trips to the neighboring towns. You won't be disappointed with a ride across the countryside. In The Master of Verona the time is the early 1300's and war is brewing between these two municipalities. Those troubles will ultimately culminate with Verona's warrior prince Alberto bringing Padua under his dominance. This was the same Alberto who was a great patron of the arts. Without his protection and financial support, Dante might have never been able to create his master works of literature. This is the backdrop for The Master of Verona as Dante and his eldest son Alaghieri become swept up in all the intrigue, rivalry and feuds of the time.

Amazingly, there are still remnants of architecture, sculptures and paintings from this era which you can enjoy as you set out on your modern tour of Verona and Padua. Imagine coming close to something that is over seven hundred years old. That is truly walking in history's footsteps.

Back to the Future In Verona

As a city, Verona is romance personified. Nestled between the Adige River and Lake Garda this ancient burg can trace its origins all the way back to the 3rd century AD. Today, your first stop in Verona should be to Casa di Giulietta or Juliet's House. Although she might have been a fictional creation of Shakespeare, there is a myth around this beauty which attracts lovers and those seeking love from all over the world. This special Renaissance style home is open to visitors and is complete with a balcony where you can leave a note for the wish of a perfect love. For good luck, make sure to rub the right breast of the bronze Juliet statue in the courtyard.

For a true stroll back in time, you'll want to carve out some time to visit the Basilica di San Zeno Maggiore. Built to honor the city's patron saint it took several hundred years to complete. Today, the beautiful 15th century frescos remain in all their splendor for you to marvel at. There are many other historic churches like the Chiesa di San Fermo and Chiesa di Sant' Anastasia that should also be added to you "must see" list.

Of course, you'll be hard pressed to have a bad meal in Verona. Look for an outdoor cafe for the true Italian al fresco dining experience.

Fair Padua

In many ways Padua could be considered a "college town" if you think of a college town being established in 1222. That's when the city's famed university was founded. Today, there is a still a young, academic vibe to Padua which gives it such vitality and spirit. No trip to Padua would be complete without a stop at the Museo Civico Eremitanti. This former monetary has been converted into a treasure trove of historical artifacts and works of art. Speaking of art, you'll also want to spent time lost in wonders of the Basilica di Sant'Antonio which is the final resting place of this beloved saint. Make sure to give yourself some "quiet time" to just sit and take it all in.

Staying Secure

To complete your Italian trip planning you need to think about covering all the bases. That can be accomplished with a simple, yet comprehensive, travel policy. Back in Dante's day, there was no guarantee that you would arrive at any one destination unscathed. Between robbers and outbreaks of the plague no vacation was guaranteed safe! Today, you can add a layer of protection with a policy that can make sure your trip won't be hindered by any type of inconvenience. It's the kind of peace of mind which will let you enjoy your walk through history.

January 30, 2013

Truth, Motive, & Tone

A huge component to what writers of Historical Fiction do is

write about real people. That’s a huge component of what the readers are

looking for – not just the clothes and habits of a distant time, but the

flesh-and-blood beings who wore those clothes and had those habits.

One type of HF novel that take a fictional lead character

and sets him or her in real places, interweaving them into the action – Lymond,

Sharpe, Flashman, Aubrey, to name just a few stellar examples.

Then there’s the other kind, when the author takes a real

person, a person who existed in history, and breathes new life into them on the

page. Penman’s Dickon, McCullough’s Caesar, Gortner’s Isabella, Moran’s

Nefertiti all leap to mind amid a wide sea of others.

Having done both, I find the first far easier. Inserting

fictional characters with their own backstories, motives, and desires into

history is great fun, allowing them to influence real events while not needing

them to conform to someone’s facts. In those novels, real people become the

supporting cast, fixed points that my fictional ones can move around.

To me, writing a novel entirely about real people is far

more challenging. Bad enough if it’s someone obscure, largely forgotten by

history (like, say, Dante’s son Pietro). It’s even more daunting to take

someone already famous and write a tale that is at once interesting and true –

true to history, true to our perception, and true to the zeitgeist, how the

culture perceives that person.

I’ve found that writing a real person well depends greatly

upon three things: Truth, Motive, and Tone.

Truth is most often thought to be found in facts – who did

what, when. Some people are better documented than others, which is both a help

and a hindrance – more signposts to guide the story, less wiggle-room to play.

Yet facts don’t tell the story. Motive does. Because the

best stories don’t just tell us what the person did. They give us the why. And

the why should surprise us. Figuring out why historical figures did what they

did is the great joy in these kinds of novels, and I think why most of us write

and read them. It’s like being a detective, examining clues among the sources

to determine the link of events that brought Caesar to cross the Rubicon, or

Elizabeth to order the death of her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots.

To me, it’s also important to flout preconceptions. If I’m

telling the readers what they already know, why am I writing? Which brings us

not just to character motives, but the author’s as well. Take for example

Sharon Kay Penman’s portrayal of Richard III, which turns Dickon into a noble

and good man, thus flipping Shakespeare’s version on its head.

Shakespeare himself performed a similar feat with Brutus.

Until he set his quill to inking down the play Julius Caesar, Brutus lived in

Hell with Judas and Cassius, the great betrayers. But Shakespeare’s play has

revivified Marcus Brutus, redefining him for the last four hundred years as an

honorable man who did a bad thing for the right reasons. That’s the power of a

good story.

That’s also the tricky part. The author’s motives matter

just as much as the character’s. For example, when writing The Master Of

Verona, I fell in love with Cangrande della Scala, worshipping him just as much

as my lead character did. So I had to turn it around and give him feet of clay.

Because no matter how much you admire or loathe a figure from history, it’s

important to keep them human. Archetypes are not, in themselves, interesting –

look at the plays from the early English Renaissance, the Mystery Plays with

characters like Greed and Charity doing battle. Those are far less interesting

than complex and contradictory people. No one is just one thing. Which is why

Shakespeare’s plays are still read today the world over, while the Mystery Plays

have vanished entirely.

Shakespeare. Elizabeth. Mary, Queen of Scots. Theatre. I’m

not using these examples lightly – though in Her Majesty's Will I’ve treated

them very lightly indeed. Which brings us to the final aspect of determining a

good novel – Tone.

Most often the tone of Historical Fiction is serious – This

Most often the tone of Historical Fiction is serious – This

Is What Happened. These are the novels I love. Yet there always are exceptions,

of which the Flashman novels but one brilliant example of where the author’s chief

intent is not to inform or educate, but simply to entertain.

That was my aim with Her Majesty's Will, which is a romp and

meant to be. I don’t for a second want anyone to take the novel seriously,

except as a rollicking good story. Because while I’ve contradicted no fact, I’ve

not hewed close to the probable either. This is a wonderful What-If, a

ridiculous conjecture about how Will Shakespeare came to London, before he ever

set his quill to paper, and accidentally became a spy.

Which, oddly, brings us back around to Truth. Just as in

Shakespeare’s silliest plays there are glimpses of human truths, it was my aim

to portray a Will Shakespeare who, if he didn’t exist, should have. Even if the story I tell is preposterous, I wanted to

breathe life into Will and Kit and the rest of my cast in a genuine way, giving

glimpses of the people I think they were. Or could have been. Or might have

been.

That was my Motive – through a ridiculous Tone, explore the

gaps in the Facts to expose a Truth. I’ll let you judge if I’ve succeeded. Just

know that I was smiling the whole time I wrote it.

December 7, 2012

Virtual Blog Tour!

This week and next I'm touring the interwebs, collecting reviews, giving interviews, and writing guest posts for 20 different websites, all through the auspices of the amazing and wonderful Amy Philips Bruno over at Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours. Click here for a list of all the sites and dates.

Among the ones over the last couple days has been a guest post over at A Bookish Affair on how to write real (ie historical, factual) people, as well as reviews for The Master Of Verona, Colossus, Her Majesty's Will, and one of those wonderful rare reviews of Voice Of The Falconer. That's the trouble with sequels, I suppose - everyone has something to say about the first one, and less about those that follow. So I'm still eager to hear what people think about Falconer and Fool. (Oddly, Colossus is my least-reviewed book on Amazon, but is fairly well represented on blogs and Goodreads, so I have a sense of how readers are enjoying it.)

So check them all out, and keep coming back for the next 14 days for more about the books and from me. I even wrote a post about vampires! (Seriously, I have a vampire novel in mind). So don't miss out!

November 14, 2012

Writing Process? What Writing Process?

One of my readers, Kate, was inspired by something I said over on my Facebook page, and she wrote a post about teaching her students Creative Writing. In a coda, she posted this:

I'm fascinated by the process authors use to write because I want to learn how they create. When I am writing a blog post or an essay, I start with my subject or theme and then the post evolves as I write. I go with the flow instead of planning everything out beforehand. I just write and wander on the page and the style evolves during the editing process...

Teachers, writers, and authors, how do you write and what other tools have you found that students could use? Does your muse hit you on the head with divine inspiration while in the moment? Or do you go charging in with a map of what you will write and leave your strategic mark?

(Full post here)

I can only answer for myself (though I will be dragging my friend Alice into this in a moment). For me, inspiration comes from the space between stories. I tend to be inspired by holes in stories that already exist, be it history or Shakespeare or what-have-you. 'How did the feud start between the Capulets and the Montagues?' 'Where was Shakespeare during his "lost years?"' 'What was the crisis that made Clemens...?' (Well, I can't reveal that one without giving away the whole Colossus game. Same with my idea for an Othello series, or my novel about the Devil). But for me inspiration comes from unexplored territory.

Here's an example. I love the movie Somewhere In Time. Always have. But in thinking about it, I have a question - when Christopher Reeve sees the penny, and starts getting sucked back to his own time, he reaches for her. What if he got hold of her? What would have happened then?

It's a silly question, an irrelevent aside. But that question, right there, was enough to spur my very first novel (the one that lives in a drawer).

When I was a kid, Marvel Comics had a series called "What-If..?" They took famous moments in Marvel history and asked what would have happened if the story had gone another way - what if Gwen Stacy had lived, what if Rick Jones had become the Hulk, etc. Now, that leads into the world of alternate-historical fiction, which is not my cup of tea. I'm not interested in changing what happened in the story. I'm interested in the parts of the story we don't see. But still, questions like What-if lead to interesting places.

So that's where my initial ideas come from - holes in history or stories. Untold stories between stories. Which, oddly, sets me up to know the ending first. Every project I dive into, I'm writing towards a known ending. I just have no idea how I'm going to get there.

What next? First I have to figure out my characters. I look to history for that, and if history doesn't help, I'll invent someone who can somehow intertwine all the events I have planned.

Next, I'm clueless, so I cast about for help. Since I'm writing Historical Fiction, this is where research comes in. For me, all the good stuff happens in the research. Dante was in Verona at this time? And he mentioned the Capulets and Montagues? And Josephus was in Rome right after the Great Fire, when they executed Saint Peter? And on and on.

Even the small things come from the research. During the writing of Voice Of The Falconer, I was stuck. Cesco was being chased through the streets of Verona, and he needed to slip into a house unseen to meet young Romeo. I already had lots of roof-climbing and wasn't interested in more just then. So I went back through my notes, and found a scrawled something about "death doors." While we were honeymooning in Verona, some friends of ours took on on a walking tour. As we passed a house, the husband casually pointed out a death door. In the Middle Ages, the living and the dead could not use the same door in a house. So there were these waist-high doors built into the larger houses used only for allowing the dead to exit the premises. So being at death's door was a real thing.

Naturally, Cesco being Cesco, he decided to enter via death's door. Voila, a scene is born, with great prophetic import and a whole lot of fun.

I cannot tell you how many times research has answered whatever question I was having. Now, that might be cheating, I don't know. But if I'm ever stuck, I hit the books and look for some new detail to hang a scene on.

Back to Kate's question. My answer is this: inspiration makes you want to write the story, and the rest is just plugging through. My process is to have my idea, have my characters, have the research behind me, and dive in to see where it all leads me. If I'm being true to the characters, they lead me, they surprise me. Human interaction is at the core of all drama. I don't go in knowing exactly what everyone will do, and I won't force my characters to do something they wouldn't (I hate when watching a movie or reading a book, a character does something completely stupid in order to further the plot). I don't want to know everything before I write a scene, or a chapter, or a book. For me, writing is a process of discovery.

Whereas my dear and gifted friend Alice Austen knows every word before she sets it down on the page. She has it all laid out before she ever sits down. I couldn't do that. If I know what's going to happen, how it's going to happen, there's no joy in the writing for me. But Alice is a far more elegant, eloquent writer than I. Her writing is deep and far from my pedestrian, workman-like prose. So her process works spendidly for her.

Which brings us to the awful, wonderful truth - there's no one secret to writing. There's just writing. Each person's process is going to be different, and it won't work for everybody else. You break out in a sweat over a class deadline. I hated writing for classes, too. But then I had a friend who hadn't written anything and needed to turn something in, and suddenly I wrote him a story (this was in high school, and yes, I know it was wrong). Suddenly I was free! It became a joy to try to write stories in other people's voices, telling the tales I thought they would tell.

It was a lesson I would re-learn years later. Not the cheating. How to free myself to write.

I make a lot of references to The Novel That Lives In The Drawer. I wrote it when I was 19. I was very, very, very proud of it. I poured my heart into it. And now, 20 years later, I am considering dusting it off and seeing if there's anything good in there. But part of me wants it to stay in the drawer forever. Because that was the novel that freed me.

How? By pouring myself into that novel, by writing about my own personal hopes and dreams and fears in thinly-veiled "fiction," I somehow managed to get past my own ego. I didn't want to write about ME anymore. I wanted to write stories. That novel was the one I had to write so I could get out of my own way.

People today like to ask if Pietro is me, or if I'm Cangrande (God, I wish), or Judah or Marlowe or any of the cool characters I write about. And I say, no. I am not a character in my books (except when I have Petruchio sparring with Kate - that's me and Jan).

But seriously, I couldn't write the stories I do if I were concerned with me, David. My focus is on the story, the characters, the structure (structure is hugely important, and I'm certain to screw it up on the first draft, and even the second or third. Structure reveals itself to me, and is never, ever what I think it is at the outset).

To sum up, David's tricks to writing are as follows:

1 - Be inspired by the space between stories

2 - Research

3 - Let the characters be true to themselves, never force them to do something they wouldn't

4 - Remove your ego, get out of your own way

But remember, ask any other writer and they'll tell you something completely different. What you have to do is try everything, and see what works for you.

It was probably a longer answer than Kate was looking for, and a bit rambly. But it's the end of a long day of writing. I hope it made some sense. Just remember - there is no spoon.

Prolific? Not so much.

I've been asked, due to how much I'm able to produce, if I sleep. Yeah, I do. I need 7 hours, or I'm pretty useless. And my productivity has plummeted since I became a father (that's not a complaint). Back when I banged out The Master Of Verona, I had a lot of 10,000 word days. My best was a 22,000 word day.

These days 5,000 is a good day. (Today was good). But I'm also a better writer, and better editor, than I was ten years ago. I'd rather have 5,000 good words than 20,000 ones that have to be pared, replaced, and eventually cut. (The second draft of MoV was 300,000 words. The one St. Martin's bought was 192,000.)

I don't know if that makes me prolific. But it does keep me busy.

October 23, 2012

Teaser 1 - The Prince's Doom

October 16, 2012

Colossus - The Historical Note

This is something I weighed including in the first Colossus novel. I think it will appear in the third, outside of the text. It's an historical note to set the scene for the whole arc of the series. I wrote it at the urging of my agent, who saw it as necessary back when this was all one enormous novel (I still plan, someday, to piece it all together, if only to see how utterly unwieldy it is). As I was working on the next Colossus novel today, I was looking at this and realizing how valuable it is on its own. So, without any further fanfare, the preface to Colossus:

Three thousand years

ago, the Hebrew king David captured a small town on the ridge separating the

Mediterranean from the Dead Sea. Renaming it Jerusalem, he made it the capitol

of his new kingdom, Israel. His son Solomon built a magnificent Temple there

for the worship of the Hebrew god.

After four hundred years

the city was conquered, the Temple destroyed. It took another sixty years for the

Hebrew people to return, building a Second Temple on the site of the first.

Conquered again by

Alexander, Israel passed from hand to hand until a leader called Makkabi led a

fight for independence. For a hundred years Jerusalem was its own master once

more, until it was captured by the Roman general Pompey. In 37 BC, Mark Antony

gave the land around Jerusalem to one of Rome’s client-kings, Herod the Great, with

a new name – Judea. For the next hundred years unrest simmered between Romans

and Jews.

Rome itself was changing

drastically. Founded two hundred fifty years after David created Jerusalem, the

humble City of the Seven Hills had grown to encompass far-flung peoples, gods,

and customs. Unable to cope with such sprawling growth, the Republic gave way

to single rule, a family dynasty called Caesar.

The Caesars maintained

order by providing free sustenance and spectacle – bread and circuses. Roman

appetites for both swiftly grew, forcing the Caesars to create larger and more

elaborate entertainments, on a colossal scale.

To fuel its new empire,

Rome required the profit that came from conflict. Lands were conquered – or

reconquered – to fill Caesar’s purse. There is nothing so profitable as war.

Under client kings and

pampered priests, all genuinely fearful of what war with Rome would bring,

Judea resisted the impulse to throw off its yoke. Frustration gave birth to

many off-shoot sects of the main religion, a religion despised and feared by

the Romans as one they could not absorb. The Hebrew god was exclusive, owning a

private relationship with his Chosen People who awaited the promised coming of

the Messiah, a divinely appointed leader who would guide them back to

independence and freedom.

The wise among both

Romans and Jews feared the promised change, for they understood that before

anything new could be built – from amphitheatres to religions – all that had

gone before must be destroyed.

October 15, 2012

Free Copy of Colossus: Stone & Steel - TODAY ONLY!

We're only a couple months away from the second installment of this series about the Roman-Jewish wars of the first century AD, leading to the destruction of the Second Temple and the building of the Colosseum! So start reading COLOSSUS: STONE & STEEL now so you'll be primed when COLOSSUS: THE FOUR EMPERORS hits the digital stands!