Alison McGhee's Blog, page 46

April 10, 2011

What I've Been Reading

I've been on a reading binge the last three weeks. Below are the books I've read, along with a one-sentence –yep, one sentence, sue me– review.

I've been on a reading binge the last three weeks. Below are the books I've read, along with a one-sentence –yep, one sentence, sue me– review.

1. Borrowed Finery, by Paula Fox. Much of the power of this unaccountably moving memoir of a young girl rejected by her parents and moved from place to place throughout her childhood comes from Fox's decision not to examine the past, but only to tell it, exquisitely, in one detailed fragment after another.

2. Aloft, by Chang-rae Lee. This first person account of a Long Island man at first turned me off by its chattiness and what I assumed would be a predictable mid-life trajectory, but by the end it had achieved a richness and depth that brought a lump to my throat.

3. Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer 1943-1954 by Jeffrey Cartwright, by Steven Millhauser. On the surface, this book is a parody of a literary biography, but that, in combination with its exquisite description of childhood, psychological acuity and a stunning twist of an ending, blew me away. I loved this book and will never forget it. (Okay, that was two sentences, but this book totally deserves more than one sentence.)

4. Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, by Amy Chua. Read all the reviews, saw the scathing letters to the editor, listened to the NPR interview, and decided I had to see for myself what the big fuss was about before I joined in with the excoriators: Lo and behold, I found her honest, self-deprecating, fearless, willing to stand with the courage of her convictions and funny as hell to boot.

5. The Full Cupboard of Life, by Alexander McCall Smith. When the brutality of the world threatens to pull me under once and for all, I go to the store and buy another in the #1 Ladies Detective Agency series, and Mma Ramotswe and Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni lift me up and remind me that gentleness, decency and kindness are still out there.

6. Get a Life: You Don't Need a Million to Retire Well, by Ralph Warner. And isn't that a good thing (the not needing a million part) – idly scanned this while waiting for my daughter in a thrift store, was taken by its practical advice on living a good life (more friends, more goodwill, more of what makes you happy, less worry about money, seeing as there's an entire industry based on making you fear that you will never have enough of it anyway), paid $1.69 and finished it at home.

7. Atlas of Remote Islands, by Judith Schalansky. Beautiful, haunting book of real places and (sometimes; it's hard to tell) imagined stories behind them, complete with hand-drawn maps; a book that I keep beside my bed along with a bunch of poetry books, the better to read one entry at a time before dreaming.

April 8, 2011

Have You Been There Too?

Driving hundreds of miles in the dark, heading north, two-lane road, high beams lighting the night, shiny eyes of deer waiting in the ditch. A fox. A feral cat.

Driving hundreds of miles in the dark, heading north, two-lane road, high beams lighting the night, shiny eyes of deer waiting in the ditch. A fox. A feral cat.

The only station drifting in and out is an oldies station, "the songs of your life." Is the first time you've known every single song that a station plays? It just might be. One after another, you beat time on the steering wheel and sing along. For once you know almost all the words. You open the windows –it's late, you're tired, you don't want to get drowsy– and the trees rise up on either side of the road. Your children aren't in the car to tell you to stop singing, so you sing.

Peace Train comes drifting in and you're 16 and an exchange student, living with a Portuguese family, not long uprooted from their Angolan home near a coffee plantation, in Lisboa for the summer. Your Portuguese sister, Angela Paula Vieira Lopes, loves Cat Stevens and plays his records every day. Strange to hear English here in this non-English world, the first time you've ever been without language.

The blue wallpapered high-ceilinged room in the small apartment that you shared with her. The single hard-mattressed bed you shared. The overhead light with the push-button switch. What is that thing on the toilet? That thing is a bidet. But what is a bidet for? You never quite have the courage to ask, and all summer long, you wonder.

Your host sister's almost non-existent English, your few words of Portuguese.

Nao falo Portuguese, mas comprehendo um cadeinho.

That sentence is probably wrong –grammar, spelling– but it's the sentence you recited all summer long, all summer as you rode the buses with your Portuguese sister and little brother, Paulo, who would point to his cheek and say beiju, beiju, and laugh when you kissed him.

Your Portuguese host mother in the tiny kitchen, making you homemade potato chips every day, making you caldo verde for Sunday supper, taking you shopping and wanting to buy you ice cream but not knowing how to ask if you wanted one. Pergunta ela, pergunta ela; her hand motioning toward you when in the presence of your host sister: Ask her, ask her.

Cat Stevens, Peace Train, Portugal. You, always the early riser, getting up before your host family every morning, going to the front door of the apartment and opening it to find the blue cloth bag of warm fresh rolls, just delivered from the bakery. The tiny kitchen table. The butter. You, rolls, butter, the silence of the early morning in a Lisbon apartment kitchen.

The gray pocked road of the north country unspools like a ribbon, winding in and out of trees, watchful animal eyes in the ditch.

Steve Winwood, Arc of a Diver. You in the late afternoon tying your long hair back, stretching before a run. The day of classes behind you, the cafeteria with your friends and the long evening stretching before you. You ran down the long hill and up the short hill, turned around and ran down the short hill and back up the long hill. A busy road. Not the prettiest run, but an expedient one that began right outside the door of the old house where you lived on the third floor.

Arc of a Diver brings Charlie R. back to you, walking by and grinning that bright smile of his. You're quite the runner, aren't you, Alison? Every day, I see you out here stretching. No, you are not quite the runner. But you smile back at sweet Charlie and head out. Up on the third floor, in her room next to yours, Ellen is playing Steve Winwood, the song drifting out the screen window into the bright air of that day.

Sixty miles to go on this long trip. The Happy Family Fast Food restaurant flashes by on your right, still open this late, and you do an about-face in the red car and pull in. Strawberry malt with extra malt, please. Small, thanks. And a fish fillet. Yes, lettuce and tartar sauce. Thank you.

Back on the road, heading north, twin eyes of oncoming cars once in a while crawling toward you out of the dark. Switch off the high beams. Remind yourself that if a deer leaps into the road ahead of you, you should not swerve. You should keep going straight. Know that if a deer does leap into the road ahead of you, you won't keep going straight. You will swerve. Remind yourself anyway, knowing that it's futile.

Pull the fish fillet sandwich out of the bag. What! This is a real fish fillet, real as in not rectangularized somewhere far away, frozen, and then deep fried in an approximation of something fish-like. This is a fish fillet in the shape of a real fish. You take a bite. My God, this is a real fish. Someone at the Happy Family Fast Food restaurant might have caught this fish herself. You're in lake country, after all. There are lakes and lakes stretching themselves across the surface of the land behind the trees, behind the woods, northern lakes full of fish.

Back on the road and the oldies station confuses itself now, allows the jarring voice of someone telling you to get on your knees right now and pray to the Lord to come blaring in. You turn the volume down just as Neil Young comes crooning on. Comes a Time.

Now you're back in time, many years ago. It's a bright blue-sky day and you're standing outside a building, a tall brick building among others. Where are you? Where is this place? It's your sister's college, that's where it is. What are you doing there? You don't know. You can't remember. But that is where you are, and your boyfriend came along, and you can't find him. Where did he go?

People next to you are pointing and looking up, shading their eyes against the sun. You follow their gaze and there he is, redhaired boy, scampering up the side of the tall brick building. His fingers find a grip among the bricks and so do his feet, again and again, and up and over and up and over he goes. He's three stories above the ground now, and a crowd has gathered to watch him.

He's a human fly! says someone, and the others agree and laugh, but quietly. Tense. No one among them has ever seen such a thing before. You have. You have been with this man many times, walking along, when suddenly he stops, taking the measure of the building next to you, the one you wouldn't have noticed. And then poof, up he goes.

You have a photo of him from back then in crampons halfway up the side of what looks to be a sheer ice wall, ice pick in hand, looking down and laughing. Is there any memory you have of him in which he's not laughing? His face was made for merriment. The force of his laughter used to bend him double, and everyone around him would laugh too.

The people in the crowd now gathered around you shake their heads in amazement. The human fly has made it to the top of the brick building. No ropes. Nothing but hands and feet and the tensile strength of a body made to climb. Buildering, he calls it. He looks down and waves and laughs. Your parents are next to you now, shaking their heads and laughing too.

Years later you will see his happy, smiling face on the cover of Rock and Ice magazine. It will not surprise you.

Not far to go now, on this late night. You are tired. Very tired. So late at night, and will the doors of the inn be locked when you get there? Probably. This is not New York, after all. You're in the middle of the woods.

Come, hear, Uncle John's band, by the riverside. And again you're back in time, on your knees, scrubbing someone's kitchen floor. But where? Where is this now? Colorado. You have a job as a hotel maid for the summer but this is not the hotel. Now you remember. You took on some extra work, cleaning the apartment of some guys once a week. Again the sky is bright and the air is crisp and you're up high, high in the mountains.

You're playing their stereo as you clean up their mess, singing along with the Dead. One of the guys, the one who pays you, comes home just as you're finishing up.

"You like the Dead?" he says.

"I love the Dead!" you say.

He shakes his head. "No you don't. Not really."

"Yes really," you say. "Really really. I just went to see them last week."

Again he shakes his head. "Have you sold everything you own and followed them around the country in a van, Alison? Do you wear flowers in your hair and tie-dye and dance for hours before every concert? Do you have set lists for every concert they've ever given for the past ten years?"

You look at him. The answer is no, to all those questions, and you both know it. You are a girl with a summer job in Colorado. You will soon leave, and he will be looking for someone else to clean his apartment once a week.

"A true Deadhead," he says, "knows exactly what her purpose in life is."

What is your purpose in your life? All you know, right then, is what it isn't.

Here you are many years later, driving through the dark, the remains of an extra-malty strawberry malt next to you, watchful eyes in the ditches on both sides of the road. All these songs are making you cry, but you can't cry because then you'd lose control of the car. Every memory these songs bring shimmering up is bright and clear and full of laughter, full of love. Your throat hurts with the weight of unshed tears.

April 2, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Dean Young

What tends toward orbit and return,

comets and melodies, robins and trash trucks

restore us. What would be an arrow, a dove

to pierce our hearts restore us. Restore us

minutes clustered like nursing baby bats

and minutes that are shards of glass. Mountains

that are vapor, mice living in cathedrals,

and the heft and lightness of snow restore us.

One hope inside dread, "Oh what the hell"

inside "I can't" like a pearl inside a cake

of soap, love in lust in loss, and the tub

filled with dirt in the backyard restore us.

Sunflowers, let me wait, let me please

see the bridge again from my smacked-up

desk on Euclid, jog by the Black Angel

without begging, dream without thrashing.

Let us be quick and accurate with the knife

and everything that dashes restore us,

salmon, shadows buzzing in the wind,

wren trapped in the atrium, and all

that stills at last, my friend's cat,

a pile of leaves after much practice,

and ash beneath the grate, last ember

winked shut restore us. And the one who comes

out from the back wiping his hands on a rag,

saying, "Who knows, there might be a chance."

And one more undestroyed, knocked-down nest

stitched with cellophane and dental floss,

one more gift to gently shake

and one more guess and one more chance.

–

For more information on Dean Young, please click here.

March 31, 2011

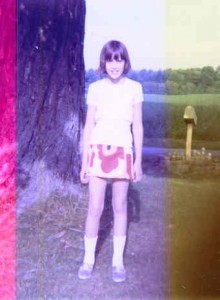

from a photo in the Times

Before he uploaded that photo of you on his page, there were other photos of you, many of them, and we have them all. We have boxes of them. And we have books that your mother tucked photos of you into, books with acid-free pages, organized chronologically, each one labeled with a date and description in black Sharpie. Somewhere there's a photo of her pregnant with you, hands holding up her swelling belly. Photos of you with your big sister, hovering over you? Dozens of them. She's pushing you in your stroller down the sidewalk. She's trying to give you a bottle. She's standing beside you next to a Christmas tree bright with lights. You and her on the first day of school, every year. I'm picturing them now, all those photos of you. Splashing in the kitchen sink. Smearing spaghetti on your face in a high chair. On a tricycle. On a bicycle. On rollerblades. On ice skates. Come with me now, into the house, down the hall with the row of framed school photos, you, shoulders back and hair combed, smiling for the camera. Oh that must be first grade, that's when you lost your first tooth. Third grade, remember that sweater? Birthday parties, family reunions, restaurant dinners. Prom. High school graduation, there you are in your robe and there you are turning the tassel to the other side, and there you are throwing it into the air, and there you are standing in front of that big quarter-sheet cake, the one that says Congratulations Graduate in green icing. College now, and summers home, and there you are with that haircut you hated, and there you are in your new bathing suit, and there you are with your new boyfriend, the one we all liked, and there you are with that other one, the one we weren't so sure of, and here you are, standing in the doorway of your first apartment, yes, that's it, that right there is your first apartment, and how you loved it, and how we loved that you were so happy there, and remember the first time you made us dinner there, and you bought those tall white candles and we admired them, they were so grownup, and you were so grownup, pouring us wine and bringing out that dessert, what was the name of it, and us refusing seconds but urging thirds on you because you were thinning down, that's what happens when girls turn into women with busy lives and busy jobs and friends and so many things in their lives to love, they get thin, they're going going going all the time, and let's go back and just look at you in this doorway again, your first apartment. We're going to put this photo away now, because this apartment is the one where we found you, honey, where we found you, baby, beautiful girl, girl we loved and tried to keep safe your whole life long, wanted to keep safe your whole life long, would have laid down our lives to keep safe. We will not look at this photo anymore. We will put it away now. So many photos we have of you, hundreds, thousands, and that one, the one we didn't take, the one he took, he who didn't know you, didn't love you, didn't care about you, didn't didn't didn't didn't didn't know you didn't love you didn't want to keep you safe is the one that the world saw, because he put it up for the world to see. And is his mother out there, and is she sitting in a dark room now, holding a box of photos of her little boy, because even he was a little boy once, everyone in this world is someone's child, and that is what he forgot, or chose not to remember.

Before he uploaded that photo of you on his page, there were other photos of you, many of them, and we have them all. We have boxes of them. And we have books that your mother tucked photos of you into, books with acid-free pages, organized chronologically, each one labeled with a date and description in black Sharpie. Somewhere there's a photo of her pregnant with you, hands holding up her swelling belly. Photos of you with your big sister, hovering over you? Dozens of them. She's pushing you in your stroller down the sidewalk. She's trying to give you a bottle. She's standing beside you next to a Christmas tree bright with lights. You and her on the first day of school, every year. I'm picturing them now, all those photos of you. Splashing in the kitchen sink. Smearing spaghetti on your face in a high chair. On a tricycle. On a bicycle. On rollerblades. On ice skates. Come with me now, into the house, down the hall with the row of framed school photos, you, shoulders back and hair combed, smiling for the camera. Oh that must be first grade, that's when you lost your first tooth. Third grade, remember that sweater? Birthday parties, family reunions, restaurant dinners. Prom. High school graduation, there you are in your robe and there you are turning the tassel to the other side, and there you are throwing it into the air, and there you are standing in front of that big quarter-sheet cake, the one that says Congratulations Graduate in green icing. College now, and summers home, and there you are with that haircut you hated, and there you are in your new bathing suit, and there you are with your new boyfriend, the one we all liked, and there you are with that other one, the one we weren't so sure of, and here you are, standing in the doorway of your first apartment, yes, that's it, that right there is your first apartment, and how you loved it, and how we loved that you were so happy there, and remember the first time you made us dinner there, and you bought those tall white candles and we admired them, they were so grownup, and you were so grownup, pouring us wine and bringing out that dessert, what was the name of it, and us refusing seconds but urging thirds on you because you were thinning down, that's what happens when girls turn into women with busy lives and busy jobs and friends and so many things in their lives to love, they get thin, they're going going going all the time, and let's go back and just look at you in this doorway again, your first apartment. We're going to put this photo away now, because this apartment is the one where we found you, honey, where we found you, baby, beautiful girl, girl we loved and tried to keep safe your whole life long, wanted to keep safe your whole life long, would have laid down our lives to keep safe. We will not look at this photo anymore. We will put it away now. So many photos we have of you, hundreds, thousands, and that one, the one we didn't take, the one he took, he who didn't know you, didn't love you, didn't care about you, didn't didn't didn't didn't didn't know you didn't love you didn't want to keep you safe is the one that the world saw, because he put it up for the world to see. And is his mother out there, and is she sitting in a dark room now, holding a box of photos of her little boy, because even he was a little boy once, everyone in this world is someone's child, and that is what he forgot, or chose not to remember.

March 30, 2011

Poem of the Week, by Rainer Maria Rilke

Go To the Limits of Your Longing

Go To the Limits of Your Longing

- Rainer Maria Rilke

God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.

Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don't let yourself lose me.

Nearby is the country they call life.

You will know it by its seriousness.

Give me your hand.

–

For more information about Rilke, please click here: here.

March 27, 2011

Portrait of a Friend, Vol. 2

You must have known her from kindergarten on, although it was in middle school that you became close friends.

You must have known her from kindergarten on, although it was in middle school that you became close friends.

She lived in a small bright green ranch house right across the street from the middle school, which was right next to the high school, which meant that all she had to do was walk out her front door, cross Route 365 –the main street of the town– and there she was, at school.

Unlike you, sitting on that accursed bus, groaning and lurching its way around endless curve after endless curve, down from the foothills, 45 minutes or more to school.

In your memory she is always smiling. She had silky dark brown hair, parted in the middle, falling over her shoulders. Her nose was sharp and red and a bit hooked, and her eyes, in your memory, are blue, blue blue.

And the smile. A big, merry smile that showed off her high cheekbones. You can picture her in the yearly school class photo. She would have been in the back row, with you, because when you were kids she was tall, too. She would have been smiling that big happy smile.

In middle school the two of you used to escape at lunch and walk across the street to the bright green ranch house. She lived there with her older brother and her older sisters and her mother, who was, you're pretty sure, a teacher down in Utica. Her father had died when she was a baby.

Her sisters and brother were in high school, unimaginably older and cool. They were hippies. You and she were too young, you missed out on that. But often, when you walked into that little house with her, they would be there. Lying on the old couch, sitting on chairs, laughing and talking and wrestling and making offhand comments and jokes about things like sex and drugs and rock 'n roll.

Had you been alone you would have been stunned and cowed and half-paralyzed by their coolness, their easy laughter. But you weren't alone. You were with her.

Why did she like you? In retrospect you were quiet and reserved and an observer and not much fun, although maybe you're not the best judge of that.

But the reason why she liked you is easy: she liked nearly everyone. She had a huge and generous heart. She was also unafraid of things that you were afraid of, like saying out loud that which scared you, hurt you, made you angry. She was honest about things. She saw life clearly, and stating the obvious didn't scare her.

The boy you had a crush on used to ask if he could have a punch off your lunch ticket.

"Sure," you used to say.

"I'll pay you back," he used to say

You would watch him run across the grass, back into the school. You and she were nearly to Route 365 now, ready to zip across and into the safety of that little green house.

"He won't, you know," she observed. "He won't pay you back. And you'll give it to him tomorrow if he asks."

You looked at her. She looked at you and smiled. She was wise. She was honest. She stated things the way they were. And she was unjudging.

Into her house the two of you would go, breaking the school rule, although in retrospect it's hard to imagine that any number of teachers didn't see you zipping across that street every day and mentally shrug.

The cool older siblings and their cool older friends might be lounging about. She would greet them all, smiling, and then the two of you would go into the tiny dark kitchen and pour enormous glasses of milk. Stir in the Quik with tall-handled spoons. Dig the knife into the big jar of peanut butter and spread giant swaths of it on slices of Wonder bread.

You'd sit eating and drinking, trying to overhear the conversations in the other room. Trying to get some sense of what life could be like, were you cooler and older and wore tight bell bottoms and peasant shirts.

She was one of the few friends you kept in touch with after high school. She stayed there, in the tiny town, population 300. She went to college, sure, but she never wanted to leave the town.

You? You left at 18 and never went back other than to visit your family. Not that you didn't, and don't, love it there, love the way you grew up.

But staying there never felt like a choice. For her, there was no other.

"I love it here," she said. "I want to live here my whole life."

She got a degree in gerontology and worked with old people. She loved them too. People on the fringes, people unnoticed, people quiet and shy, she saw them. She noticed them.

Twice that you know of, because she told you, men asked her to marry them.

"I said no," she said. Smiling that big bright smile.

You asked her why. She shrugged.

"Didn't feel right," she said. "I don't know. I'm happy just the way I am."

She was Catholic and that, too, was something she loved. Hers was a happy Catholicism, a big bright generous religion whose God was always with her.

Everyone in the town knew her. At the drugstore, at the one tiny bar, at the church, in the one tiny grocery store, at the bank. She was one of those rarest of creatures, a human being completely comfortable in her own skin.

She's been gone twelve years now, but you think of her every day. Every morning, you talk to her. Picture her.

When she appears in your mind, it's always in winter. She's always brushing up against you, wearing a bright blue nylon parka. That dark hair, those blue blue eyes, that grin.

When you pour a glass of milk and stir in some Quik, you make a toast to her. When you and some of her other friends organize an annual fundraiser in her name, for an annual scholarship in her name given to a high school kid in that little town, you do it for her. When you write your annual check to the food bank in that little town, you fill in the "in honor of" box in her name.

If she were still here, she'd no doubt be running the place.

You wish you could go home and see her again. Walk into that bright green house and have a peanut butter sandwich. You'd go to the bar with her, let her introduce you around.

March 24, 2011

A few things I saw this morning

Five pelicans, flying in formation, skimming low over the water on the lookout for fish.

Five pelicans, flying in formation, skimming low over the water on the lookout for fish.

A thirteen-year-old golden retriever lower himself to his haunches in the surf, then clamber out on the sand and wiggle ecstatically on his back.

Bubbles rising silently in a straight-sided copper bottom pot. The same pot a few minutes later, shimmering and shaking over a wide red coil of heat.

The bright black eyes of a squirrel fixed on mine as he advanced down a branch and toward my waiting palm.

Tan foam that looked like dirty whipped cream, surfing in on the waves that fold and retreat, fold and retreat, fold and retreat, at the shoreline.

A woman wearing a long white shirt and black shorts, bent at the waist and peering intently at something only she could see in the water.

An uninhabited wooden platform, like a treeless treehouse and taller than all of the few surrounding houses, standing sentry in a white sand lawn.

The silent, slender t-shirted backs of two sleeping teenage girls.

The far-apart vanishing footprints of someone who must have been running in the sand.

A transparent, blue-rainbowed sea creature blown up on the beach, shaped like a Chinese dumpling and trembling in the wind.

March 22, 2011

A footnote in someone else's story

That mask there to the right, modeled by an old friend, is one you used to wear every Halloween. Then you had children and it terrified them, so you put it on a high shelf and haven't worn it since.

That mask there to the right, modeled by an old friend, is one you used to wear every Halloween. Then you had children and it terrified them, so you put it on a high shelf and haven't worn it since.

Recently, it resurfaced when you were attempting a deep-clean of the furnace room. You put it on and the vinyl smell of Halloweens past came flooding through you. You remembered walking into a bar many years ago and watching through the eye slits as people stared.

"That girl's face paint is amazing," one woman whispered (the mask falls a bit short on your friend's face but fits yours perfectly).

Now the mask is in one of the drawers in your closet. It hung on a hook for some time in there, drooping down among many scarves, but it unnerved you to come upon it late at night, so into the sock drawers it went.

You used to love wearing it. You could feel anything behind that mask and no one would know. So freeing. Your mother used to tell you how much she loved wearing a uniform at the tiny private school that had given her a scholarship.

"No one knew how poor I was," she said. "We all looked the same. It was wonderful."

What this mask has to do with being a footnote in someone else's story, you're not sure. But it does. That's something you've learned over these years, that free association means something.

You can learn a great deal by closing your eyes. Separate yourself from the way a person looks, and you will instead focus on the way he smells.

You can learn a great deal by closing your mind, too – by ignoring rationality. The rational mind doesn't always know best, or know much of anything. There are aspects of a person that you can't articulate in words, but that you know way deep down. The problem is that we're taught out of that way of knowing someone; we're trained out of it early on.

Everyone has a story, a story of why she's in this life, what she's meant to do here. You come into the world knowing it, fully sentient, and then you forget. Or it's trained out of you.

Many people are hurt in some way, looking for something to mend a fracture of some sort. Others don't know they're looking to mend something. They can't articulate it to that extent; they're blind, and searching. Grasping. They grasp on to those who have the capability –the fault line?– to respond to them.

Those who allow themselves to be grasped believe, on some level, that they are fracture-menders. Or that they can be.

It can take a combination of seeming paradoxes –the passing of years and the unlearning of what you've been trained– to move through the world on your own terms. Even to know what your own terms are. It's the work of a lifetime, and no one can do it but you.

Begin with smell.

Your body knows things that your mind doesn't. Stay away from someone whose smell you don't like. You don't have to be cruel or rude, but there's a reason you should stay away. No need to question your instinct; obey it.

Leave sight out of it. Sight is the least trustworthy of the six senses.

Sound is somewhat trustworthy, or rather, it can be if something in the voice you're listening to makes you tense up, turn wary. If this happens, stay away.

Touch can also be trustworthy, but it becomes clouded by sex and physical attraction, and neither of those can be fully trusted.

Taste? Not applicable, most of the time, except under those circumstances that also involve sex and physical attraction, and the same can't-be-fully-trusted rule applies there too.

That leaves smell –trust it– and your sixth sense. That's the most reliable of all, but you usually have to shut down the other five senses in order to know what, at heart, is going on.

Do that. Shut down. Put the face-paint mask on. Listen to what your sixth sense is telling you. Let yourself know what you already know.

Some things to keep in the back of your mind:

Charm and charisma are measured out on one side of a scale. Something else is on the other side, in equal measure.

Certain expressions will flit across a face very briefly, in a fraction of a second. Other people in the same room might not see what you saw. But you did. Don't discount this.

Some people in this world want you, need you, to be a footnote in their story. But anything that comes in italics, like that word need? Be careful.

The other side of the wariness scale is unwariness, and that too comes in equal measure. The same rules apply to unwariness as well, except that you can trust sight and touch more, over here on the unwariness side. This side of the scale is lighter, so you can fit more on it.

Over on this side is where you meet the people who, when you close your eyes, give off light. Stand tall. Look at you with kind and curious eyes. Smell familiar. You can trust this, too.

March 13, 2011

Portrait of a Friend, Vol. 1

You met her fourteen years ago. She was tiny then, and now, at 90, she is even tinier.

You met her fourteen years ago. She was tiny then, and now, at 90, she is even tinier.

The first time you met her she grasped both your hands in her own pale arthritic ones. You felt a shock of recognition that transcended the 40+ year difference in your ages, and she felt it too.

She has often spoken of it since: "We are soul sisters." She believes that your connection was formed long ago, before this life, and that it will continue after this life.

She has glossy, jet black hair that frames her face, and she often wears black and red. Bright red sweaters, a bright red coat, black pants, a black shirt. She's beautiful. She shines. Light surrounds her.

For almost sixty years she's lived in a fifth-floor walkup in midtown, first with her husband and now, for the past twenty years, alone. You've met her neighbors, five of them, and you've seen how they too adore her. One of them brings her mail up, one helps with groceries, another helps her down and outside and into a cab, should she want to go out.

Which she does. She goes out a lot, to dinner, to see friends, to ceremonies that honor her work as an artist.

You've never seen her apartment but you imagine it: crammed with books and artwork and Chinese furniture –she is Chinese-American, born and raised in San Francisco and New York– and lovely fabrics. She is the kind of person who surrounds herself with beautiful things, and beautiful things are drawn to her.

Although you didn't meet her until you were all grown up, you knew her work much earlier. She is an artist, and some of the picture books you read when you were a child contain her artwork. Thirty years before you met her in person, her art was part of your mind and memory.

Arthritis has taken so much of her limberness away, crippling arthritis that takes her three hours each morning to overcome enough to get out of bed. Once, she was trapped inside her apartment for a day because she couldn't turn the doorknob and open the door.

She falls sometimes, and some of her friends –she has many friends– scoop her up. When asked if she's okay she laughs. She has a high, tinkling laugh; it sounds like small windchimes.

"Of course!" she says. "I only weigh 65 pounds, like a child. Falling doesn't hurt."

She calls you sometimes, usually when you're making dinner.

"Oh, what you are you making, my darling treasure?" she says, and you tell her, and she exclaims how delicious it sounds.

You call her sometimes, too. You hate talking on the phone but for her, you'll do whatever it takes. You let the phone ring and ring and ring: arthritis. She has no answering machine, and sometimes you let it ring thirty or more times. And then she picks up.

"Hello?" she says.

"Hello!" you say, and she knows right away who it is.

"I had a feeling you might call," she says, and then you're off and running, usually for no more than ten minutes, minutes full of I love you's and laughter.

Her voice is so young. She is so young. That's one of the things you're realizing these days, that it's the body that ages, not the spirit.

"Goodbye, my precious darling," she says.

Her father's name for her when she was a child was Precious. He held her on his lap and read her stories. Her mother cooked for her. Her uncles and aunts played with her and took her wandering through the city.

"I grew up surrounded by love," she says, "nothing but love. How could I not be happy?"

After you hang up, you go back to your work, and fifteen hundred miles away, she goes back to hers. Soon she will be 91. You have a box of notes she's sent you over the years, not so much notes as tiny pieces of art. Someday you'll frame them all and hang them on your wall, so that whenever you look at them you'll feel her presence again, her light and sparkling presence.

March 5, 2011

Rain

I'm thinking about rain today.

I'm thinking about rain today.

It's been a long time since I saw rain. Heard it. Felt it. We are not in a drought, but there has been no rain for many months now. Rain has fallen, but not in its original form.

What was once rain, what would still be rain were it not so deadly cold, has been reincarnated and is now living a new, white, silent life. This reincarnated rain doesn't sink into the ground or pool at the corners of the streets. It stays above ground and grows ever higher.

I miss rain. I miss puddles. I miss earthworms stretching themselves on the pavement after a rain.

I miss the smell of wet pavement. I miss rain that falls silently and softly, disappearing into the black earth of my garden. I miss rain that drums earpoundingly on the tin roof of a one-room cabin in Vermont.

I miss the first drop of rain, cool and wet, falling on my cheek when I'm an hour's walk away from home. I miss the questioning look in my dog's eyes as he, rainhater, turns his head up to me as the rain begins to fall. I miss running on the beach when a storm is blowing in.

I miss crouching in the clearing under the weeping willow as rain streams down the long leafy branches above and around me. I miss reading in the hay fort with my flashlight on a rainy summer day when I'm too far into the bales to hear it but it's all around me nonetheless.

I miss the way rain calms the air, makes it possible to pull a brush through my hair without those snaps and crackles, tiny lightnings, rising about my head.

My middle name is pronounced Rain. Pilipalapilipala is the Chinese name for the sound of falling rain. Rain pocks the surface of the ocean when it falls, dimples the rushing water of the river. My astrological sign is Cancer, a water sign, and water is what I crave: rivers and creeks and lakes and ocean.

The title to one of my books came to me as I pedaled fast around a lake in a thunderstorm. I could not, would not, live in the desert.

In spring, rain comes bubbling up out of the ground, forms itself into rivulets and creeks, goes tumbling down the hill and into the river, and to the great waters beyond. This will happen soon.