Alison McGhee's Blog, page 23

August 13, 2013

Andes Mint #29: “This that I see now.”

At the beginning of the Minneapolis summer (qualified as “Minneapolis” summer because this year it began about three weeks ago), I decided to re-read my favorite and most influential books from childhood. The ones I hadn’t already re-read more than once, that is, including:

At the beginning of the Minneapolis summer (qualified as “Minneapolis” summer because this year it began about three weeks ago), I decided to re-read my favorite and most influential books from childhood. The ones I hadn’t already re-read more than once, that is, including:

1. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, by Betty Smith. 2. My Side of the Mountain, by Jean Craighead George. 3. Swiss Family Robinson, by Johan Wyss. 4. The Member of the Wedding, by Carson McCullers. 5. Bambi, by Felix Salten. 6. So Big, by Edna Ferber. 7. How Green Was My Valley, by Richard Llewellyn.

My sister Oatie was the inspiration behind this decision. She reads an enormous amount and she has excellent taste, and a year or so ago she told me that she re-reads A Tree Grows in Brooklyn every year.

I thought about that for a while, this re-reading of our favorite childhood book. I pictured Oatie lying on the couch in her living room in New Hampshire, absorbed in the story of Francie’s life. She must know it perfectly by now. I admired that.

I didn’t know how she had the guts to do it, though, because every time I have thought about that book, all these years between elementary school and now, my heart has felt cracked.

Doesn’t something bad happen to Francie in that book? Something really bad? That was all I could come up with, for the way the words a tree grows in Brooklyn made my heart hurt.

But if my sister Oatie, who has a heart the texture of a melted marshmallow, could read it every single summer, then so could I. I went to Magers & Quinn and bought a new copy, the one you see relegated to the bottom of this page because, per usual, I couldn’t figure out how to make it smaller.

It took me a while to get through the book, partly because I’m a slowish reader and partly because I kept turning down the corners of pages so that I could go back and copy out the beautiful passages that made me keep stopping. This is something I do with all the books I most love, and then I never do go back and copy out the passages, and that is why my bookshelves are filled with books that have turned-down pages. Good intentions, good intentions.

I copied out this, though, in Francie’s voice.

The last time of anything has the poignancy of death itself. This that I see now, she thought, to see no more this way. Oh, the last time how clearly you see everything; as though a magnifying light had been turned on it. And you grieve because you hadn’t held it tighter when you had it every day.

What had Granma Mary Rommely said? “To look at everything always as though you were seeing it either for the first or last time: Thus is your time on earth filled with glory.”

I read and re-read those passages. To look at everything, and everyone, as though you were seeing it either for the first or last time.

That little guy to the left, the one in my arms, is my baby nephew. He’s a few weeks old now, just easing himself into this world. Sometimes he catches his breath the way that newborns do, as if he can’t quite remember how to take that next one.

That little guy to the left, the one in my arms, is my baby nephew. He’s a few weeks old now, just easing himself into this world. Sometimes he catches his breath the way that newborns do, as if he can’t quite remember how to take that next one.

He will stare at a scrap of white paper with black lines on it for minutes and minutes at a time, utterly absorbed. Everything about the world is new to him.

For one moment in time, my nephew was the youngest person in the entire world.

I think about that sometimes, when I walk the sidewalks of the city. I look at the people scurrying or sauntering or drooping by, and I think: Everyone was once someone’s baby.

To look at everything always as though you were seeing it either for the first or last time.

Let me look upon you, elderly woman carefully holding your one-pound weights and stepping up one step and down again, up one step and down again, there in the stairwell of the Y, as if this is the last time I will ever see you. Let me smile at you as I duck around the corner on my way to the weight room.

Handsome man that I always hope to see when I walk into the weight room, if this is the last time I will ever see you, let our eyes meet and let me admire you even more than usual today.

Man at the front desk who swipes my card, let me look at you as I leave, and ask about that book you’re reading, and wish you a good day in this beautiful weather, because what if this is the last time I will behold you?

Walking Man, as my daughters and I call you, oh Walking Man whom I have watched walking the streets of this city for 20 and more years, only in the last three years slowing down, let me imprint on my eyes the sight of you sitting now, on that bench on Hennepin, you with your hands folded on your lap and your feet in their brown shoes planted on the sidewalk and your slow nod when our eyes meet as I pass, for this may be the last time.

Beautiful girl with the tumble of dark curls spilling down your back, those green eyes of yours, let me hug you before you go upstairs to pack up your clothes, because. . . no. No, no, no. Never. For you, green-eyed girl, I will look upon you as though I were seeing you for the first time.

This that I see now, she thought, to see no more this way. Oh, the last time how clearly you see everything; as though a magnifying light had been turned on it. And you grieve because you hadn’t held it tighter when you had it every day.

It took me a while, but I finished A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I used to be afraid to re-read the books I loved so much when I was a kid, because I figured that through my grownup eyes, I would think they were terribly written.

They’re not. They’re beautiful. They’re in my bones. It was partly through those books that I learned how to see the world. How to translate what I saw and how I felt into words on a page.

The terrible thing that I was sure had happened to Francie, the thing that I couldn’t remember but was so afraid of re-reading? Nothing specific. Nothing that doesn’t happen to everyone: heartbreak, courage, sorrow, love, loss.

August 12, 2013

Andes Mint #28: My magical friend K

It was many years ago that I met K. In my memory, she came up to me in one of the marble-floored halls of a turreted building on the east bank of the University of Minnesota, took my hands in hers, and said, “I’m K. Who are you?”

It was many years ago that I met K. In my memory, she came up to me in one of the marble-floored halls of a turreted building on the east bank of the University of Minnesota, took my hands in hers, and said, “I’m K. Who are you?”

That memory has to be wrong, but nonetheless it’s how I remember meeting her. It’s something she might have done, that much I know – see a young woman with a big pregnant belly ease her way into a chair around a big table, make a mental note to get to know her, then find her in the hallway and take her hands. Yes, that’s something K would have done.

I was young, she was a few years older, and I remember her looking at my belly and then looking up at me. Still holding my hands.

“You’re going to have a baby,” she said. “How wonderful.”

This was my second baby, and even though I wanted it, I was exhausted, couldn’t stop throwing up (morning sickness, for some lucky women, lasts until the minute the baby’s born) and overwhelmed. But there was something in her soft voice, something in the way her head was tilted as she spoke.

“Do you want one too?” I said.

“Oh, I do,” she said. “I do want a baby. But I’m afraid it’s too late.”

Those are my first memories of K. So long ago now. From that day forth we were friends. She was –and is– a beautiful woman with a soft voice that always sounds, to my ear, full of air. As if her voice belongs to the sky. She is slender, and light on her feet. She doesn’t make much sound when she walks.

Back then, in those long-ago days of grad school, we used to sit in workshops together and communicate telepathically. We reacted the same way to certain comments, suggestions, and styles of teaching. We followed up afterward when we met for coffee or tea or dinner at the King & I. We were of like mind.

At that time, K lived in a sublet, a studio in downtown Minneapolis. I remember it as full of clothes and books and papers and photos.

That soft, air-filled voice of hers, her gentle touch, her lightness, belied an underlying steel. Grit. Determination. I used to laugh inside sometimes, watching how she’d tilt her head at a cutting comment in workshop, smile that beautiful smile, and say, “Okay. . . okay.” I knew exactly what was happening inside her, knew that that gentle okay meant anything but.

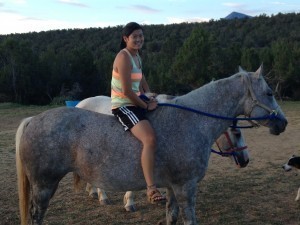

Back then, K longed for horses. She longed for the west. I think now that what she really longed for was freedom. Freedom, for her, meant a horse that she could jump on and ride for hours, through land where she would see no one else. Freedom meant wide-open space, huge mountains that she could ski down all winter long, rangeland where animals far outnumbered humans. Freedom meant a child to pour her prodigious love into, a child she could raise to be as fearless as she was.

Back then, K longed for horses. She longed for the west. I think now that what she really longed for was freedom. Freedom, for her, meant a horse that she could jump on and ride for hours, through land where she would see no one else. Freedom meant wide-open space, huge mountains that she could ski down all winter long, rangeland where animals far outnumbered humans. Freedom meant a child to pour her prodigious love into, a child she could raise to be as fearless as she was.

I remember when she got pregnant. Solo didn’t matter to her; she had no fear of raising a child by herself. I remember being as thrilled for her, almost, as she was. By then we were long out of grad school and she had moved to Texas.

I remember a phone call, when she was halfway through that pregnancy, which broke my heart; hers was already broken. Sometimes babies, no matter how much you want them, don’t come together inside you in a way that’s going to let them live once they’re outside.

I remember getting on a plane and going down to Texas to hold her hand through an awful procedure that she would never in her life had chosen to go through. It happened before dawn, in a locked room in a locked hall of a locked building; it had to, for safety. Why do so many try to make a private, agonizing decision a matter of public policy?

She took a few years after that to pull herself together, and then she became the mother of a little girl from a faraway country. The last time I saw K, until last month, was twelve years ago, when she came briefly to Minneapolis over the holidays.

My only memory of that visit was of sitting on a couch I’d found on the curbside and dragged into the living room of a new apartment. She wrapped her arms around me as her baby girl hauled herself around on the floor and I cried and cried and cried; I too was going through something awful.

Flash forward to a month ago. My youthful companion, herself a girl who longs for horses and wide-open rangeland and the peace that comes with that, was going to work on a ranch in Colorado. K had been living in Colorado for years by then.

“You have to come stay with us,” she said, in response to a Facebook post of mine in which I had asked for suggestions of good hikes in southwestern Colorado. “I insist. My horses insist. My daughter insists. You are coming.”

Twelve years stretched between the last time I’d seen her. But a while ago I decided to say yes to every invitation that comes my way. And this was an invitation from K.

So out we drove, to find ourselves winding around a dirt road that went on for miles, me laughing because somehow, it was only fitting that K –who began in a rented studio in downtown Minneapolis, remember– would end up here.

As we drove farther and farther from anything that felt like people-world, we began to see horses. Dogs. This felt like K, like a place where she would live. My youthful companion pointed out her window at the slightly insane sight of a dog leaping wildly at a sprinkler, over and over and over.

We turned the car off when we could go no farther. There was a house perched on hundreds of acres of Colorado high desert. We were still laughing at the insane sprinkler dog when we got out of the car.

We turned the car off when we could go no farther. There was a house perched on hundreds of acres of Colorado high desert. We were still laughing at the insane sprinkler dog when we got out of the car.

“This has got to be her place,” I said to my youthful companion. “This is exactly K’s kind of place.”

The air was dry and warm and filled with the scent of sage, that high desert smell that I remembered from living in Colorado during summers long ago. My youthful companion and I stood in the drive and looked around: horses in the open grassland, heads down and tails switching.

Dogs everywhere, racing each other down the field or lying in the shade of giant sunflowers. Chickens, clucking and pecking by the side of the house. A potbellied pig, waddling across a muddy patch of irrigated garden.

K emerged from the house. A parrot clung to the top of her head. Her daughter followed, holding a rabbit in her arms.

I gave her a hug, still laughing. The parrot leapt from the top of her head to the top of mine. I spread my arms wide and turned around.

“So this is you,” I said.

“This is me,” she said.

It was her: all that open land. All those animals. Ten chickens and five dogs and two cats and one rabbit and two pigs and seven birds and ten horses. All of them, with the exception of one cat and the chickens, rescue animals. All with names. All loved, all understood in a way that most humans don’t understand animals.

That is K. That is how she’s always been.

“So you finally have your magical menagerie,” I said. “The menagerie you always wanted.”

“I guess I do,” she said, looking around. “I guess I do.”

“And the dogs don’t eat the chickens and the cats don’t eat the birds and nothing chases the rabbits and everyone is free to go in and out of the house,” I said. It wasn’t a question; I already knew the answer. “How do you do it?”

“I don’t know,” she said in that same soft, sky-filled voice. “It all just works.”

So that is how the youthful companion and I came to spend an enchanted three days in the high desert, sleeping in a room with a rabbit and two dogs and a couple of potbellied pigs and a chicken or two wandering in and out. The youthful companion and K’s daughter rode bareback through the rangeland. We sat on the deck drinking wine and watching a full moon rise over the mountains to the east.

Some people are drawn earthward as th e years go by. You can see them on the sidewalk or walking up a set of stairs, their heads down, backs curved, that earthward tug calling them down. Hard to stand up straight.

e years go by. You can see them on the sidewalk or walking up a set of stairs, their heads down, backs curved, that earthward tug calling them down. Hard to stand up straight.

Others are drawn skyward. They lighten. Their bones hollow out. Whenever they want they can turn in all directions and see the enormous horizon. Hard to keep anchored to the surface of the world.

I’m sitting on my couch right now thinking about K, how filled she is with air and light. A sky person.

How clearly I can still see her green eyes that day in the marble-floored hallway when I first met her, here in the city in which I still live. How I can feel her hands holding mine that day, telling me how much she wanted a baby. Horses. Animals and animals. A life in the country.

I’m thinking about how twelve years can pass with only an occasional Christmas card between two friends, and how –when it all works– that doesn’t matter.

How sometimes you can drive a thousand miles and end up on a dirt road in the midst of hundreds of acres of juniper and sage, to find someone you love having winnowed herself and her life down, funneled it all into the exact life she was meant to live.

August 11, 2013

Andes Mint #27: Chapter One

Once, somewhere in this world, not long ago and not far from where you are reading this, it was the middle of the night on a quiet block in a city of canyons. Everyone who lived in the tall brick apartment buildings that lined either side of the street was asleep. Sleeping children. Sleeping grownups. Sleeping cats and dogs and birds and mice.

Once, somewhere in this world, not long ago and not far from where you are reading this, it was the middle of the night on a quiet block in a city of canyons. Everyone who lived in the tall brick apartment buildings that lined either side of the street was asleep. Sleeping children. Sleeping grownups. Sleeping cats and dogs and birds and mice.

There in the middle of the night on that quiet city block, everything was dark except for the street lamps on either end. The lamps shined down from their tall poles and made pools of light that illuminated a few squares of sidewalk before the dark closed in again. In a few hours, when the sun began to rise on the far side of the river at the edge of the city, the street lamps would switch off. The sky would lighten. Everyone who was sleeping would begin to stir.

For now, the honking of cars and the revving of motorcycles and the beep beep beep of reversing trucks were absent. Had you been standing there, you might have assumed that nothing was happening, nothing except sleep and silence.

But that wasn’t true.

At the far end of the block, in front of a triple-locked and shuttered storefront door, a small dog lay sleeping. This dog was familiar to the inhabitants of the block, although no one knew his name. Everyone who had noticed him trotting along the sidewalk, day in and day out, assumed that he lived with someone in an apartment. Or that he belonged to a shopkeeper and lived in the shopkeeper’s store. Or that he was a restaurant kitchen dog who went home with a busboy or a sous-chef and a bag of scraps at the end of each long night.

They were all wrong.

The truth was that the small dog had no home. If he belonged to anything, he belonged to the block itself. He hadn’t been there long. No one knew exactly how old he was, but if you looked at him carefully you would have seen that he was young. A puppy, maybe.

The street lamp shined down on the orange letters written in swirly script on the whitewashed stone above the door.

Sanjeev’s Store.

As he slept, the small dog nosed and scrabbled and sighed and panted. Maybe something was chasing him in his dream. Maybe he was trying to hide from someone. Maybe he was too hungry to sleep well. The door to Sanjeev’s Store was locked, and in his sleep, the dog pushed himself tight up against the door, so that if it opened suddenly, he would roll right inside.

Had you been standing there that night, on that block of sleepers and dreamers not far from where you are reading this, you might not have known that anything was unusual about the block. But it wasn’t an ordinary place. The tops of the two tallest brick buildings were often draped in clouds, so that their inhabitants looked out on soft whiteness instead of clear air. Sound around the cloud dwellers was muffled. Telephones didn’t work in those apartments, and neither did televisions or radios or computers or anything else that most other people took for granted.

There was something else unusual about the block, a dark and hidden something, but it would take two children –Miranda and Bernard– to figure that out.

No, it wasn’t an ordinary place at all.

Maybe that’s why, even if someone had noticed the small dog huddled against Sanjeev’s Store in the middle of that one night, he wouldn’t have thought twice about him. No one was there, though. No one noticed when a lone car stuttered around the corner and then came rocketing down the street. The car’s lights were off. Its engine revved and its brakes squealed as the driver, peering through the windshield, tried to avoid the street lamp looming up next to the store.

The driver never saw the small dog, confused and terrified by the sudden noise, leap up and skitter away from the door. The radio in the car was too loud for the driver to hear the crunch as the dog was flung into the air. As he ricocheted off the fender. As he collapsed in a heap on the sidewalk. All the driver knew was that somehow he had managed to miss the street lamp, and that made him happy. So he stomped down on the gas pedal and careened on down the empty street, swung left through the red light and was gone.

August 10, 2013

Andes Mint #26: Poem of the Week (novel excerpt), by Louise Erdrich

Excerpt from “The Painted Drum”

- a novel by Louise Erdrich

Life will break you. Nobody can protect you from that, and living alone won’t either, for solitude will also break you with its yearning. You have to love. You have to feel. It is the reason you are here on earth. You are here to risk your heart. You are here to be swallowed up. And when it happens that you are broken, or betrayed, or left, or hurt, or death brushes near, let yourself sit by an apple tree and listen to the apples falling all around you in heaps, wasting their sweetness. Tell yourself that you tasted as many as you could.

–

For more information on Louise Erdrich, please click here: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/louise-erdrich

–

My Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#!/pages/Alison-McGhee/119862491361265?ref=ts

August 9, 2013

Andes Mint #25: By the Numbers

Zip codes in which you have lived: 13354, 02114 (past), 55408 (current), and 05346 (also current). Apartments: six. Houses: four. Bathroomless one-room cabins in Dummerston, Vermont: one. Children, two of whom are now as tall or taller than you: three. Neurotic cats: one. Hyper dogs who remain meth-head-like no matter how much you exercise them: one. Broken bones: two. Trips to Italy: two. Times fallen in love: five. Eyeballs lasered: two. Days spent rising before 5 a.m. to write until you wrote a book good enough to be published: 5,476 minus approximately 1500 spent despairing of talent, lacking in work ethic, or too damn tired = 3975. Shoe size: ten. Minutes per running mile: a sad nine. Ability to alpine ski, despite having attended a college with its own Snow Bowl: zero. Novels read: approximately 900. Trips to China: three. Times spent slapping then-four-year-old son in middle of night when you were exhausted and he would not let you sleep: one. Times spent despising self for slapping then-four-year-old son in middle of night when you were exhausted and he would not let you sleep: countless. Trips to Taiwan: two. Novels written (published or soon to be): 11. Novels written (that will never be published): 3.5. Trips to Paris: one. Vows to stop saying the f-word in front of children: countless. Times vow to stop saying the f-word in front of children has been broken: countless. Ratio of children’s picture books written to those published: approximately 30:1. Best friends named Ellen Harris Swiggett: one. Marriages: one. Divorces: one. Trips to Portugal: two. Regrets: a few. Poems read before dawn daily: three. Current favorite adult beverage: vodka gimlet, up, in a martini glass. Friends and family members seen through cancer treatment: seven. Trips to Turkey: one. Mountain that can be glimpsed in leafless seasons from top of acreage in Dummerston: Monadnock. Shortest length of hair: one inch. Longest length of hair: three feet. Shade required to maintain hair’s unnatural color: Cool Light Brown. Trips to London: one. Exact pre-dawn times at which you typically wake: 2:47, 3:20, 4:54. Strong cups of coffee drunk before dawn: .7. Men who, upon noting length of fingers, have asked if you can palm a basketball: approximately 18. Times you have palmed a basketball: none. Times heart has been broken: five. Trips to Mexico: ten. Pairs of tomato-red suede pants: one. Times spent dreaming that you are driving up an increasingly vertical road until your car tips backward and you fall into a bottomless void: at least 46. Times spent dreaming that you are short one chemistry class and therefore cannot graduate: at least 37. Letters written to grandmother before she died: approximately 570. Lindt Milk Chocolate Truffles consumed: approximately 2100. Times spent practicing Chopin’s Prelude in F Minor without noticeable improvement: approximately 233. Trips to Bhutan, Morocco, Macchu Picchu: none. Yet. Times daily you think how lucky you are to be living this big fat life: at least three.

Zip codes in which you have lived: 13354, 02114 (past), 55408 (current), and 05346 (also current). Apartments: six. Houses: four. Bathroomless one-room cabins in Dummerston, Vermont: one. Children, two of whom are now as tall or taller than you: three. Neurotic cats: one. Hyper dogs who remain meth-head-like no matter how much you exercise them: one. Broken bones: two. Trips to Italy: two. Times fallen in love: five. Eyeballs lasered: two. Days spent rising before 5 a.m. to write until you wrote a book good enough to be published: 5,476 minus approximately 1500 spent despairing of talent, lacking in work ethic, or too damn tired = 3975. Shoe size: ten. Minutes per running mile: a sad nine. Ability to alpine ski, despite having attended a college with its own Snow Bowl: zero. Novels read: approximately 900. Trips to China: three. Times spent slapping then-four-year-old son in middle of night when you were exhausted and he would not let you sleep: one. Times spent despising self for slapping then-four-year-old son in middle of night when you were exhausted and he would not let you sleep: countless. Trips to Taiwan: two. Novels written (published or soon to be): 11. Novels written (that will never be published): 3.5. Trips to Paris: one. Vows to stop saying the f-word in front of children: countless. Times vow to stop saying the f-word in front of children has been broken: countless. Ratio of children’s picture books written to those published: approximately 30:1. Best friends named Ellen Harris Swiggett: one. Marriages: one. Divorces: one. Trips to Portugal: two. Regrets: a few. Poems read before dawn daily: three. Current favorite adult beverage: vodka gimlet, up, in a martini glass. Friends and family members seen through cancer treatment: seven. Trips to Turkey: one. Mountain that can be glimpsed in leafless seasons from top of acreage in Dummerston: Monadnock. Shortest length of hair: one inch. Longest length of hair: three feet. Shade required to maintain hair’s unnatural color: Cool Light Brown. Trips to London: one. Exact pre-dawn times at which you typically wake: 2:47, 3:20, 4:54. Strong cups of coffee drunk before dawn: .7. Men who, upon noting length of fingers, have asked if you can palm a basketball: approximately 18. Times you have palmed a basketball: none. Times heart has been broken: five. Trips to Mexico: ten. Pairs of tomato-red suede pants: one. Times spent dreaming that you are driving up an increasingly vertical road until your car tips backward and you fall into a bottomless void: at least 46. Times spent dreaming that you are short one chemistry class and therefore cannot graduate: at least 37. Letters written to grandmother before she died: approximately 570. Lindt Milk Chocolate Truffles consumed: approximately 2100. Times spent practicing Chopin’s Prelude in F Minor without noticeable improvement: approximately 233. Trips to Bhutan, Morocco, Macchu Picchu: none. Yet. Times daily you think how lucky you are to be living this big fat life: at least three.

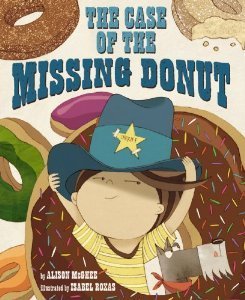

Free Donut Holes!

Free donut holes, my friends, free donut holes!

Free donut holes, my friends, free donut holes!

Available at the Red Balloon Bookshop on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, tomorrow morning (August. 10) at 10:30, when I’ll be reading that new little book over to there to the left.

“The Case of the Missing Donut.”

Stop by and say hi if you’re in town.

August 8, 2013

Andes Mint #24: The World Offers Itself to You

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,” says poet Mary Oliver, “the world offers itself to your imagination, calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting. . .” I was 18 when my parents drove me over from the Adirondacks and delivered me and my belongings to college. I remember watching them drive off in their yellow station wagon. It seemed to me that, although I hadn’t known it until just that moment, my life had broken open. As if anything was possible.

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,” says poet Mary Oliver, “the world offers itself to your imagination, calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting. . .” I was 18 when my parents drove me over from the Adirondacks and delivered me and my belongings to college. I remember watching them drive off in their yellow station wagon. It seemed to me that, although I hadn’t known it until just that moment, my life had broken open. As if anything was possible.

What do I remember of those years? Moments, one after another, held inside as if all time is one time, and we are all still together, there on that beautiful hill.

I remember asking my friend Tom, late one night at a party, “How can you fling yourself off that tower?” For years I, the non-skier, had admired ski jumpers, how they arced their bodies into the unseen air.

“It’s no big deal,” he said. We were sitting side by side in two large green chairs. “The air is soft. It’s like a pillow. It cushions you. You just go into your tuck and do it.”

What he didn’t tell me was that the “cushion” was there and then not there, and it could move you all over the place, depending on air pockets and wind gusts. I know that now, but what I have always gone back to is that first, long ago comment: You just go into your tuck and do it.

I remember stretching to Steve Winwood’s Arc of a Diver before heading out on late afternoon runs. I remember Charlie R’s sweet smile as I ran past him one day near Hillcrest. I remember smiling back. Out of all those days and years of running, why that one fall day, why Charlie alone, walking through falling maple leaves turned to flame? But there it is, a memory like a photograph.

And I remember sitting in a Social Anthropology class, listening to others discuss the assigned readings, through which I had dutifully plowed (50 pages read = one Andes mint bought at the Crest Room, prior to the night’s studying). I remember Mima N. shooting her hand up and asking a brilliant question. I remember thinking, “How did she even think up that question?” It was clear to me that my critical thinking skills were far behind. But anything was possible, wasn’t it? Maybe someday I, too, could think up, if not a great answer, at least a great question.

I remember that on Sundays, the New York Times was delivered to the door of the girls who roomed across the hall from me sophomore year. I remember thinking, I’ve never even read the New York Times. I remember thinking, Someday, when I’m a real grownup, I’m going to have the New York Times delivered to my door.

I remember visiting my friend Absalom on the third floor of our dorm and noting that it was possible to turn one’s dorm room into a shrine to John Prine, cigarettes, and thrift store army jackets. I remember redecorating Peter C’s room with a small collection of moth-eaten fox stoles and four plastic beer mugs.

I remember driving late one night, miles and miles in the darkness, Steve K. behind the wheel, Greg M. riding shotgun, me in the backseat wishing Steve would give me another square of his Cadbury Fruit ‘n Nut. The car was quiet, and Steve beat his hand against the steering wheel to a song inside him. Where were we going? Did we know?

I remember emerging from the underbelly of Sunderland Language Center one winter night when the stars above were like diamonds scattered on black velvet. My mind rang with the cadence of Chinese voices on the Chinese tapes I had spent hours listening to. Suddenly, all around me like an invisible chorus, came the sound of cheering. It rose out of the snow and the woods and the dorms and the town, and I stood there in the cold, filled with wonder. We had just won the U.S.-USSR Olympic hockey game, but I didn’t know that. It seemed only that anything was possible. That even the mountains, if they wanted to, could sing.

I remember standing in line at Security, waiting for my i.d. card on that very first day, behind a girl with honey-colored hair and hiking boots laced with red laces. Now that is cool, I thought. If only I had the imagination to lace my hiking boots with red laces.

“Can you tell me where Stewart Dorm is?” I said to this girl. I did not tell her how much I admired her red laces. That would come years later.

“I’m heading there myself,” she said. “My name’s Ellen.”

I didn’t know then that from that day on, three decades now and counting, each of us would be the voice and the laughter that the other longs to hear. That we would see each other through hardships we couldn’t have then imagined. That if not all things are, in the end, possible, they are at least bearable, if you have a best friend.

I remember graduation day, crutching across the stage with a broken leg, crying and crying and crying, because I did not want to graduate. I wanted to stay in that shining place forever.

Now here I am, all these years later, and I’m thinking about Neil Young, who wrote, “All my changes were there.” Not all of them. But that was the place where I lived all those moments. That place was the pivot for me, the place where I first turned around and glimpsed the wide horizons of the world. In some ways, I’m still there.

Like Tom said, the cushion might be there and it might not, and gusts of wind might move you all over the place. But you go into your tuck anyway, and you aim yourself into the future.

August 6, 2013

Andes Mint #23: Synesthesia

This mint is adapted from one in the archives, because at around one last night I realized that it was no longer dark-gray Monday but mustardy-chamois Tuesday, and I started thinking about synethesia all over again.

From a question in Padgett Powell’s book of questions: “If you could assign colors to the days of the week, what color would you assign Tuesday?”

This is an odd question. It implies that you – anyone – have a choice in Tuesday’s color, when in fact you don’t. At least, in your world you don’t.

Tuesday comes with its own color, as do all the days of the week. Tuesday is a muted mustard-dun, solid color, no pattern. There’s a smooth feel to the color of Tuesday, like old chamois.

Wednesday? A clear blue. Slightly darker than robin’s egg, but on the bright light spectrum of blue. No navy, no dark. Another smooth-textured day.

Thursday is dark, similar to the ocean on a cloudy day. It’s a changeable color within that narrow realm. It can shift from dark gray to forest green, and there’s sometimes a dark honeycomb lace pattern within those dark shades. There can also be a bar of metal in Thursday, a rounded bar that occasionally emerges from within the dark, silent colors. Thursday is a beautiful day. It’s your favorite day of the week.

Friday is a patterned green, a mix of greens: the green of maple leaves in mid-summer and also the green of those leaves when darkened by rain. The pattern that shifts on the surface of Friday is the same sort of leafy light that plays across your skin when you’re lying in your treehouse. Friday is shades of green with shadows.

Saturday is gray-blue, light and porous, especially Saturday mornings. As the day wears on, Saturday darkens in shade but never solidifies; it is a day that retains its foaminess.

Sunday? Yellow, of course, although a yellow that doesn’t take its shade from the sun of its namesake. Sunday is an unchanging shade, a buttery yellow but a shade less dense than implied by the word ‘buttery.’ Sunday is an evaporating sort of day and so is its color.

Monday is dark gray but see-through. Monday is a color like looking through a fine-mesh screen window. Monday is an early color day and it stays dark screen gray until midnight, when it turns into Tuesday, and the chamois mustard-dun returns.

These are the way the days of the week appear to you. They’ve appeared this way all your life, each with its own color and texture and solid or diffuse light and patterns. You always assumed that everyone lived their days out with the same sense of color and texture, just the way that others see all the words spoken around them scrolling across the bottom of the movie screen in their brains, but guess what? Not everyone does. Strange.

August 4, 2013

Andes Mint #22: Off the grid dabblement

You’re the keeper of a tiny house on a hill in the woods in Vermont. The house is one room, 11′ x 19′, with a tiny sleeping loft and a tiny porch.

You’re the keeper of a tiny house on a hill in the woods in Vermont. The house is one room, 11′ x 19′, with a tiny sleeping loft and a tiny porch.

At first there was just land. Over the years –quite a few them at this point– you added electricity, tunneled up in a pipe from a pole down the dirt road. And a well, dug way down into the Vermont rock. There’s no plumbing, but there’s a pump. There’s also an outhouse. The outhouse has no door, but when you’re in it you’re looking out at the pine woods and a creek and a bluff rising above it, so . . . no complaints.

Then the tiny house came into being, first in the form of a kit that included lumber and a tin roof and insulation, nails even, which you bought off eBay. Some friends and you framed it up over four days in late fall and another carpenter friend finished the interior over the long Vermont winter, snowshoeing in and out because the dirt road isn’t plowed in winter.

When you’re at the tiny house you divide your time between writing –you can sit on the porch and all you see are white pines and deer and squirrels and wild turkeys and once in a while even a bear– and hiking and making things out of rocks and dirt and wood.

The tiny house could easily be off the grid except for the fact that you’re completely dependent on electricity in order to write. Solar panels are a possibility but they’re way too expensive.

Nevertheless, you play around with off the grid sorts of experiments. One is a graywater filtration system. Graywater is water that’s been used for things like showers and washing dishes. (Blackwater is what comes out of toilets, but you don’t need to worry about that because of the aforementioned outhouse.)

You built your graywater irrigation system this summer, over the course of three days. If it looks just like a raised rock garden, that’s because it pretty much is.

Day One: Eye up the patch of dirt at the side of the cabin. Haul a whole bunch of flat rocks from the creekbed at the bottom of the hill up the hill to the cabin. That sentence makes it sound so easy, doesn’t it? It’s not. Those rocks are amazingly heavy, and prying them out of the creekbed is hard, and that hill is long, and your wheelbarrow is kind of rickety. Major labor, friends, major labor.

Day Two: Arrange all those rocks you hauled on Day One into a pretty, slightly irregular shape. Accept your friend’s offer of some extra topsoil and stand with him in the bed of the pickup tossing shovelfuls into the rock bed. Go to the hardware store and buy two lengths of corrugated pipe. Lay them into the garden bed and grade the dirt underneath so that they angle slightly downward. Test-drive the pipes by pouring several buckets of water through them to make sure that the water disperses evenly and doesn’t all cascade out the other end. Adjust grading as necessary.

Day Three: Go back to the hardware store and buy a bunch of peat moss. Cover the pipes with the peat moss and then take a shovel and do a haphazard job of mixing the topsoil with the peat moss. Dig the perennials your mother helped you divide from her garden out of the woods where you temporarily planted them three days ago. Arrange them in an attractive manner in the raised rock bed. Make sure you don’t try to plant them directly onto one of the pipes.

Et voila! Now you have a raised rock garden/graywater filtration system. Someday, maybe, you’ll have some sort of rudimentary plumbing inside the tiny house, and then you can let the graywater run out of a pipe and into the pipes now hidden in your garden. For now, you’ll empty your 5-gallon buckets of graywater into the garden, which would be a pretty sweet addition to the tiny house even if it didn’t serve a graywater filtration purpose.

August 3, 2013

Andes Mint #21: Poem of the Week, by Ellen Bass

Pleasantville, New Jersey, 1955

– Ellen Bass

I’d never seen a rainbow or picked

a tomato off the vine. Never walked in an orchard

or a forest. The only tree I knew

grew in the square of dirt hacked

out of the asphalt, the mulberry

my father was killing slowly, pounding

copper nails into its trunk.

But one hot summer afternoon

my mother let me drag the cot onto the roof.

Bed sheets drying on the lines,

the cat’s cardboard box of dirt in the corner,

I lay in an expanse of blueness. Sun rippled

over my skin like a breeze over water.

My eyelids closed. I could hear the ripe berries

splatting onto the alley, the footsteps

of customers tracking in the sticky, purple mash.

I heard the winos on the wooden crates,

brown bags rustling at the throats of Thunderbird.

Car engines stuttered, came to life and died

in the A&P parking lot and I smelled grease and coffee

from the diner where Stella, the dyke, washed dishes

with a pack of Camels tucked

in the rolled-up sleeve of her t-shirt.

Next door, Helen Schmerling leaned on the glass case

slipping her fist into seamed and seamless stockings,

nails tucked in, to display the shade, while Sol

sucked the marrow from his stubby cigar,

smoke settling into the tweed skirts and mohair sweaters.

And under me something muscular swarmed

in the liquor store, something alive

in the stained wooden counter and the pungent dregs

of beer in the empties, my mother

greeting everyone, her frequent laughter,

the shorn pale necks of the delivery men,

their hairy forearms. The cash register ringing

as my parents pushed their way, crumpled dollar

by dollar, into the middle class.

The sun was delicious, lapping my skin.

I felt that newly arrived in a body.

The city wheeled around me–

the Rialto movie, Allen’s shoe store, Stecher’s Jewelry,

the whole downtown three blocks long.

And I was at the center of our tiny

solar system flung out on the edge

of a minor arm, a spur of one spiraling galaxy,

drenched in the light.

For more information on Ellen Bass, please click here: http://www.ellenbass.com/poems.php