Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 196

January 24, 2012

Placing Too Much Importance on Passion

Red Maple by Bruce / Flickr

Passion has become a cheap word. I'm starting to roll my eyes when I hear it. But it hasn't always been this way.

It all started when I read a 2010 post by Siddhartha Herdegen, "Why You Don't Need Passion to Be Successful." It was the first time I questioned one of my dearly held personal values: passion for my day-to-day work.

For the past year, I've been on the admissions committee for the E-Media Division at the University of Cincinnati, and I've become numb to students who claim, "[x] is my passion."

If true, who cares? Every other student has a passion, too. What matters is how that translates into action. Show me what you've done because of your passion. Show me through action that you really mean it and aren't flirting with it. Show me that you've struggled and remained resilient. Show me that you have discipline.

Recently, I ran across this quote:

Passion is the quickest to develop, and the quickest to fade. Intimacy develops more slowly, and commitment more gradually still.

—Robert Sternberg

I've taught hundreds of students with passion. I teach few students with commitment to do the best work possible.

I think part of the problem is how we define passion, so allow me to introduce Herdegen's definition:

Passion is a deep connection to an idea, a strong bond which creates a feeling of desire. It contains elements of both commitment and excitement but is not limited to them.

Passion plus commitment is not too common in my experience. More often you find:

a person with a passion for something but lacking talent (sometimes due to lack of ability to practice for the time required, lack of a mentor, etc.)

a person with a talent for something without a passion for pursuing it

a person with either talent or passion but no ability to commit (whether through life circumstance or otherwise)

I run into all of these types—at school, at conferences, in daily conversation.

It seems like the cultural myth these days is that we ought to be pursuing our passion; otherwise we will be unhappy. I'm not so sure that's true any more. As long as we do work that feels satisfying—that complements our personal values and strengths—we can all do just fine, especially if we have relationships that are also fulfilling and satisfying.

There's another category of person I haven't mentioned: those struggling to figure out what their passion is. The questions I then pose are:

What are you avoiding? (There's a reason, and don't feel guilty about it.)

What activities or interactions do you most look forward to, anticipate, and hope for more of?

What activities or interactions do you value or prioritize on a daily basis?

What activities can you get lost in? (Time stops; you're in the flow.)

The answers might not lead to "passion" + "commitment," but I think they help pave the way to a happier life.

January 23, 2012

When Do You Need to Secure Permissions?

Andrea Costa Photography / Flickr

With more authors publishing independently than ever, I'm hearing more questions about rights and permissions. It's a tough issue to navigate without having an experienced editor or agent to guide you.

I hope to provide some clarity on permissions in this post. Permissions is all about seeking permission to use other people's copyrighted work within your own. This means you contact the copyright owner of the work (or their publisher or agent), and request permission to use the work. Most publishers have a formal process that includes paperwork, e.g., a contract to sign. Often, you are charged a fee for the use, anywhere from a few dollars to thousands of dollars.

When do you NOT need to seek permission?

When the work is in public domain. This isn't a terribly easy thing to determine, but any work published before 1923 is in the public domain. Some works published after 1923 are also in the public domain. Read this guide from Stanford about how to determine if a work is in the public domain.

When simply mentioning the title or author of a work. You do not need permission to mention the title of someone's work. It's like citing a fact.

When you abide by fair use guidelines. If you're only quoting a few lines from a full-length book, you are likely within fair use guidelines, and do not need to seek permission. See more about fair use below.

When the work is licensed under Creative Commons. If this is the case, you should see this prominently declared on the work itself as an alternative to the copyright symbol. For instance, the book Mediactive is licensed under Creative Commons, and so are many sites and blogs.

When DO you need to seek permission? When you use copyrighted material in such a way that it cannot be considered fair use.

Crediting the source does not remove the obligation to seek permission. It is expected that you always credit your source regardless of fair use; otherwise, you are plagiarizing.

A Brief Explanation of Fair Use

There are four criteria for determining fair use, which sounds tidy, but it's not. These criteria are vague and open to interpretation. Ultimately, when disagreement arises over what constitutes fair use, it's up to the courts to make a decision.

The four criteria are:

the purpose and character of the use (e.g., commercial vs. not-for-profit/educational). If the purpose of your work is commercial (to make money), that doesn't mean you're suddenly in violation of fair use. But it makes your case less sympathetic if you're borrowing a lot of someone else's work to prop up your own commercial venture.

the nature of the copyrighted work. Facts cannot be copyrighted. For that reason, more creative or imaginative works generally get the strongest protection.

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the entire quoted work. The law does not offer any percentage or word count here that we can go by. That's because if the portion quoted is considered the most valuable part of the work, you may be violating fair use. That said, most publishers' guidelines for authors offer a rule of thumb; at the publisher I worked at, that guideline was 200-300 words from a book-length work in a teaching/educational context. Be careful whenever quoting song lyrics or poems; it is nearly impossible to use them without needing permission, unless it's an epic song or poem.

the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the quoted work. If your use of the original work in any way damages the likelihood that people will buy the original work, you are in violation of fair use.

To further explore what these four criteria mean in practice, be sure to read this excellent article by attorney Howard Zaharoff that originally appeared in Writer's Digest magazine: "A Writers' Guide to Fair Use."

Does this apply to use of copyrighted work on websites, blogs, digital mediums, etc?

Technically, yes, but attitudes tend to be more lax. When bloggers (or others) aggregate, repurpose, or otherwise excerpt copyrighted work (whether it originates online or offline), they typically view such use as "sharing" or "publicity" for the original author rather than as a copyright violation, especially if it's for noncommercial or educational purposes. (I'm not talking about wholesale piracy here, but about extensive excerpting or aggregating that would not be considered OK in mass mediums.) In short, it's a controversial issue.

What questions are you left with? What needs further clarification? Let me know in the comments.

January 20, 2012

100 Tips to Alleviate Self-Doubt

Today's guest post is from Matthew Turner (also known as Turndog Millionaire).

Do you sometimes look at your writing and want to throw up? You know the feeling, surly. One day you write something, read over it and think, "Wow, that's some rather snappy content!"

Then, just 24 hours later, you glance over it, scream at the screen and wonder how you wrote such dribble.

It's a similar feeling to when I look at pictures from five years ago, hair like a Cure groupie with a quiff nestled a good five inches above my head. Seriously, what was I thinking?

This constant tennis match of self-doubt is a regular part of my life, and I reason with myself that it's normal and everyone goes through this. Just like getting cold feet on your wedding day or panicking during a test you know you're prepared for.

The real problem here is I doubt my self-doubt! What if this self-doubt's telling me something? Maybe I should run away and leave it to the professionals?

But I keep on plugging away, because if I didn't I'd be a quitter. So I cling to the fact that others go through this, including people who have "made it" in every sense of the word. Just about every blog I come across has a post like this, describing the eerie feeling of hating your own work and discovering you're a fraud.

And I've just entered a contest on Men with Pens, the head honcho, James, opening up two free places on his writing course for those doubting their writing. At last count there were around 30 entries, and many of the posts are great, from people who definitely don't need help with their craft. Saying that, they may look at mine and think exactly the same … hmmmm, or maybe not.

So I insist that this is normal and everyone goes through this overanalyzing crazy maze of AHHHHH. Some people, like me, go through it often. Others may only feel it from time to time. But I'm insistent everyone goes through it.

I'm here to offer three tips that have helped me in my times of need:

1. Walk away from it.

I let my mind sulk, come back a day or so later and try again. If I still feel the same then I make changes.

2. Listen to music

This is a passion for me and listening to some slow and often depressing folk makes me feel better and inspires me.

3. Exercise

I'm at my most cranky when I'm tired and lacklustre, and a bout of exercise helps me snap out of it. I find self-doubt and whiney go through life hand in hand.

There you go, these are my three wise tips. Funny enough, and unsurprising I'm sure, it took me a few attempts to get to the final three. I wrote them down happily, re-read them and sulked at the screen, and eventually copied this entire article to an e-mail to Jane and already wonder if I could have done better.

But the point of this post was not for me to offer advice, but instead to come to Jane with the idea of gathering ideas from fellow writers who've been through, are going through, or feel they will one day go through this episode.

So this is the deal you've unintentionally signed up for. To leave a comment below with three tips of your own.

Maybe you're a successful author who's been through this and given sage advice to lead you through.

Maybe you've had a teacher, friend, family member, or dentist even who's given you some amazing tips to deal with this self-doubt.

Or maybe you've just read something at some point and thought, "Wow, what a great idea."

It's not uncommon for Jane to get 30+ comments for a post, which would equate to over 100 tips. You might not find my tips helpful. Hell, you might not even find Jane's tips helpful either when she leaves them in the comments. But chances are you'll find one or two in a list of 100 that will help you along your journey—not just in writing, but life in general.

So it's over to you, my fellow brother and sisters of self-doubt. Let's help each other move forward and share our unbearable self-loathing.

Matthew Turner (aka Turndog Millionaire) is a Marketing Strategist with an MA in Advertising & Marketing from Leeds University Business School. As an aspiring author, he blogs about book marketing, strategic planning for aspiring authors, and how new marketing techniques can be used in the world of publishing. Visit his website and blog.

Matthew Turner (aka Turndog Millionaire) is a Marketing Strategist with an MA in Advertising & Marketing from Leeds University Business School. As an aspiring author, he blogs about book marketing, strategic planning for aspiring authors, and how new marketing techniques can be used in the world of publishing. Visit his website and blog.

January 18, 2012

E-Book Statistics For Authors to Watch

From ebookcomments.blogspot.com

This weekend, I'll be speaking at the Writer's Digest Conference about e-publishing. I'm in the process of updating my slides and information about e-book sales—which can be a confusing and murky issue since the reporting of such sales is not as standardized as print book sales (yet).

Meaning: You can not only find various data sets, you can also find many interpretations. Above is a regularly updated graph from a blogger who has been following e-book sales reported by AAP (Association of American Publishers). It's a good visual of how sales have picked up in recent years. (Click through for more of his graphs.)

When authors ask me about what's next for the publishing industry, I try to point them to metrics to keep their eye on—since I find it hard to predict what will happen next. In that vein, here are two posts from this past week that nicely complement one another:

E-Books Outsell Print for Majority of Titles on USA Today Bestseller List by Laura Hazard Owen at PaidContent. This article points to how, after the holidays, many traditionally published titles—the commercial bestsellers—are selling more units as e-book editions. The USA Today bestseller list is unique in that it combines print and e-book sales AND indicates which edition sold more copies. What authors should keep an eye on: Watch how many of the titles sell better in e-editions versus print. (It does switch back and forth!) Also look at which genres seem to repeatedly outsell in electronic editions. It's impossible to draw any conclusions from only one week or one month, but if you watch the list for an entire year, you'll stay grounded in industry discussions about just how much e-books are "taking over" or not. Publishers Lunch (sub required) recently noted that the inclusion of e-book sales (along with print sales) in USA Today's list "barely" changed their reporting of overall 2011 bestsellers. But keep an eye on the composition of those sales.

Top Self-Published Kindle E-Books of 2011: A Report by Piotr Kowalczyk at Teleread. This helpful parsing of Amazon data helps answer questions such as: Is the 99-cent price tag for e-books wearing out? Can we expect more success stories from independent e-book authors? Will self-published e-books continue to expand? Some of the most interesting data here is the number of self-published titles in the Kindle Top 100 bestsellers. In the best months, self-published titles claimed 20-27% of those spots. What authors should keep an eye on (especially those looking to self-publish): Pay attention to the Kindle Top 100 bestsellers and if the share of self-published titles increases. Also keep an eye on what's being charged for these titles—because the more that indie authors can charge (and the longer bestseller status can be maintained), the more viable the indie route.

Finally, keep track of the appearance of self-published e-book authors on traditional bestseller lists. For instance, in USA Today's 2011 bestseller list, two out of the 100 bestselling titles were self-published e-books. For the New York Times bestseller list, during the whole of 2011, eleven self-published e-book authors made it to the list. As Publishers Lunch noted (sub required), that's not very many authors considering how widely the self-pub millionaire trend has been trumpeted. Let's see if the number grows in 2012.

Helpful links

USA Today bestseller list

Kindle bestseller list

New York Times bestseller list

Wall Street Journal bestseller list

As a side note, while writing this post, it felt antiquated how bestseller lists still segment out sales by edition (hardcover, paperback, mass market, electronic). If these lists are printed to serve and inform readers—and perhaps that's a huge assumption?—how much does this distinction matter, except to those inside the industry? How much do these distinctions serve to keep the old paradigms in place? (E.g., "hardcovers" are more important or meaningful than "paperbacks"?)

January 17, 2012

Must-Attend Sessions: 2012 Writer's Digest Conference

Speaking at the 2011 Writer's Digest Conference

Once again, I'll be speaking at the annual Writer's Digest Conference in New York City this coming weekend. They have an incredible line-up of keynote speakers (plus the infamous pitch slam), but when it comes to breakout sessions, I'd like to share my picks for writers trying to get traditionally published.

Pitch Perfect (Friday, 6 p.m.)

If you'll be pitching during the conference, it's imperative you participate in or witness the pitch practice session led by Writer's Digest editor Chuck Sambuchino. Not only is it great fun, it's the best education you'll ever get on how to pitch an industry professional.

Becoming an Author Entrepreneur (Saturday, 9 a.m.)

This session by industry professional Dan Blank overviews what critical business know-how every author needs to support a successful career.

Panel: Ask the Agents (Saturday, 10 a.m.)

Get a better understanding of what agents are looking for in a client, in a manuscript, and in a pitch.

Panel: Hard-Core Author Marketing (Sunday, 9 a.m.)

If you go to no other marketing/business session during the conference, don't miss this one. You'll be able to ask questions of a highly experienced and diverse panel. (Just try and stump them!)

My sessions at the conference include E-Publishing 101 (excellent for indie authors as well as traditionally published authors with an eye on their backlist), plus a panel focused on self-publishing.

If you would like to attend, but haven't registered yet, I have a discount code to offer you. Visit this link, add the conference to your cart, then enter WDCSPEAKER12 upon check out. You can attend for the $410 rate ($115 savings or 20% off registration).

I hope to see you there!

For more on this event:

Here's my recap of the best advice from the 2011 Writer's Digest Conference

Here's an excellent preview of conference season (including the Writer's Digest event) from Dan Blank and Porter Anderson

January 16, 2012

Why Isn't Literary Fiction Getting More Attention?

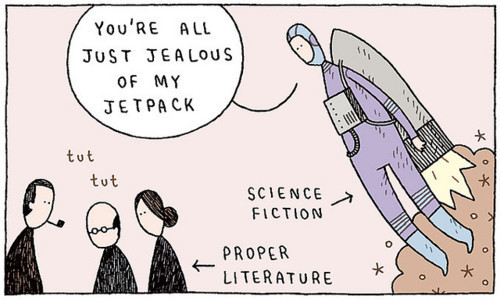

© Tom Gauld | www.tomgauld.com

Today's guest post is from April Line, a freelance writer and writing teacher. Read her previous guest post for this site, Can Children Develop Adequately Without Books?, and visit her online at April Line Writing.

When I was in the home stretch of my liberal arts studies, something kind of shitty happened. I got pregnant. Being 25, a feminist, single, and centimeters from an MFA program in fiction writing at my choice between University of Pittsburgh, University of Cincinnati, or Purdue; abortion was the obvious answer, right?

Wrong.

There's no point now in wondering whether it was the right choice, but I've got a pile of toil, an excellent six-year-old, and perspective to show for it.

What I don't have is a terminal degree in the art of my choice, and give-or-take five years of reading and writing.

In April 2011, during my kid's first year of public school, I was so relieved to reclaim a bit of breathing space that I quit my stupid retail sales job and I went freelance.

Copyblogger told me that I should tweet as a freelancer, so I did (they give great advice); and in May somebody tweeted asking, "Is literary fiction is the new poetry?"

The quotation is commonly attributed to Jonathan Franzen, but it's a sentiment that's been around for some time. I recall my mentor and undergraduate thesis advisor telling me that literary writers write for other literary writers.

Seeing it on Twitter gave it startling gravitas, plus my own burgeoning adulthood makes me more willing to see a doughnut's hole, and it's been niggling at my literature-loving soul.

And it seems that the fatalistic, academic impulse is going to be to let it just happen: to watch literary fiction's audience become increasingly smaller, watch the people who write it become increasingly disenfranchised, watch their numbers diminish, even as the growing number MFA programs churn out writers and literature lovers, and deprive us—who would rather read Amy Hempel or John McNally or Joan Didion than Stephanie Meyer or Norah Roberts or John Grisham—of this delicious, delicious, reading.

That makes me sad.

One of the last bits of literary fiction I read before taking my too-long hiatus was Ron Currie Jr.'s God is Dead. That, friends, is a brilliant book. It's loosely connected short stories set in post-apocalypse America. One of the first bits of literary fiction I read when I came back to reading for love, pleasure, and the experience was Ron Currie Jr.'s Everything Matters! which is also a brilliant book, and my new favorite. It replaced The Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England by Brock Clarke.

My point is that these books are lovely and entertaining. In Everything Matters!, there is cocaine and alcohol addiction, violence, celebrity, conspiracy, and science fiction. In The Arsonist's Guide there's multi generational marital unrest, alcoholism, violence, the mafia, fire. In both of these, there are very funny jokes.

And it seems to me that we're reading more than ever as a culture. We read on the Internet, so many folks are blogging, e-readers and smart phones make books and language so accessible and ever present. I have a copy of The Pickwick Papers on my Android phone.

It seems sad and irresponsible to me that we should just let literary fiction fizzle into the academic ether.

This article at McSweeney's references NEA studies that indicate that 1982–2003 accounted for the greatest decrease of young people reading literature. But young people are reading more as of 2009 than they did in the 30 years prior. So this new increase in young readers, combined with the decreased cost of publishing e-books, and marketing with social media, seems like an opportunity for literary fiction.

Genre authors are more likely to score five-figure advances (or more) and are almost certain to see royalties. Literary authors clamor after $5,000 advances if they don't just give up and self pub—and if they see royalties, they're spare.

Literary authors do book tours, signings, appear at academic conferences, speak on concerns of craft and the academic writing world. They have agents, but their agents don't interface with their publishers to make sure the books are on end caps in Target or the equivalent.

Why the hell not?

Literary fiction gets marketed differently because there's a different audience, right? And I can see that argument, sort of. Like if people who appreciate literature didn't also like to buy inexpensive toilet paper. Or if enjoying 30 Rock and Planet Earth were mutually exclusive. Or if nobody who listens to Howard Stern ever listens to Fresh Air with Terry Gross.

The morale among literary authors is low. Because even though they know their books are great, the mainstream voice is saying, "But not great enough to be worthy of sales efforts!" The playing field is leveling as reading becomes more digitized, and I'm not the only one who's saying it. It's time for literary authors to reclaim a segment of the market. And I want to help.

I loaded up my holiday gift list this year with titles from authors whose tweets I follow, from authors I loved seven years ago who've published new books, with writers the mainstream public doesn't talk about.

Peter Damian Bellis lives 20 minutes away from me, and has written a book called The Conjure Man (available for free here) that was in the running for a nomination for the National Book Award. There are fewer than 5,000 copies out there. It's not even in too many libraries. It's a wonderful book that will totally enthrall you, and Bellis is touring blues festivals to publicize it.

Do the people in charge of decisions about marketing books have such a low estimation of the reading public that they won't even give them the opportunity not to choose literary fiction?

I recognize that we're probably a hundred long, laborious steps away from end caps in Target, or at least equal market saturation, but we must start walking.

Here's a step: I'm starting a nonprofit. Billtown Blue Lit. We've got a blog. We've got a StartSomeGood Campaign, we're doing a podcast called "Writers Talk." We want people to have access to good stuff to read, so we're going to do good stuff in service of good books.

Maybe you'd like to join us.

April's fiction appeared in Sou'Wester in 2005. She currently does copy writing, editing, and freelances for a number of regional publications. She is working on a collection of essays and fiction, and on her nonprofit project, Billtown Blue Lit. She lives in Williamsport, PA. Visit her website.

April's fiction appeared in Sou'Wester in 2005. She currently does copy writing, editing, and freelances for a number of regional publications. She is working on a collection of essays and fiction, and on her nonprofit project, Billtown Blue Lit. She lives in Williamsport, PA. Visit her website.

January 13, 2012

Why Creative People Are Walking Paradoxes

Joe Vastano

In the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, Joe Vastano has a lovely essay on how writers have to acknowledge the duality inside them in order to achieve artistic triumph. I couldn't agree more. Here's a brief snippet:

Creative people are walking paradoxes; both shrewd and naïve, libidinous yet prudish, and so on. I believe that this paradox forms the basis of the creative tension so essential to artistic triumph—the friction of opposites setting fire to that "third thing," which goes by yet another name: the Sublime.

Go read the entire essay, "Into the Sublime," and see what other gems await in Glimmer Train's latest bulletin.

January 11, 2012

Do You Hold E-Rights to Your Traditionally Published Book?

Maistora / Flickr

I recently received this very challenging question and scenario from traditionally published author Dr. Liz Alexander.

I have an issue with one of my publishers and don't really understand where I stand.

Last year Octopus Publishing (who took over Gaia, publisher of four of my highly illustrated best sellers, including The Book of Chakra Healing and The Book of Crystal Healing—approx. 250,000 and 200,000 sales each—contacted me to say they wanted to reissue Chakras with new illustrations (it was originally pubbed in 1999) and to offer an e-edition as well as POD. It would then become a Gaia Classic!

This was one of my earliest books, I didn't have an agent at the time and because of the highly illustrated nature of the book, I ended up with 5% of net receipts in royalties. I easily earned back my advance and have been making several hundred dollars consistently on this book since publication … As with most publishers they've done nothing to publicize it, but the book is on a universal topic, has great reviews (it was very good, even if I say so myself, lol!) and could go on selling forever, I guess.

The original contract didn't cover e-versions (obviously) so they sent me an addition to sign—in which they are offering 15% of net receipts for the electronic version of the book. I said it wasn't enough and that given the amount of money they've made from my books over the years (for which I wish now I'd negotiated an escalating royalty rate —but naive at the time) that 25% was nearer the mark. They keep coming back saying that Hachette (the big owner) has a policy of X and this ties their hands. It's the kind of dinosaur belligerence that causes authors to leave publishers in droves … we're not treated like individuals, just another author—sigh!!

Anyway, I wrote back and said I wasn't going to sign my rights for 15% and was investigating publishing my own ebook version. This is what the editor wrote back:

Thanks for your response. Just to clarify, the position re ebook editions is that you wouldn't have the right to publish your own ebook (or have someone else do this on your behalf), because we ie Octopus/Gaia still own the rights in the text according to your original contract. Given we don't have the physical distribution or print cost for an ebook edition we prefer to offer a more reasonable rate than the 5% agreed at the time. Hope you understand that we're not being purposefully obstructive here, and that we'd much rather go forward with your blessing/involvement.

I'm confused about that last line: "we'd rather go forward with your blessing/involvement."

Surely they can't go ahead with an ebook version if I refuse to sign the addendum to the contract? Although I guess they are right about me not being able to bring out an ebook of my own, based on the same text?

Would be grateful for your thoughts as to how best to proceed. My mother used to tell me that I had a tendency to "cut off my nose to spite my face" but I'm a very principled person and don't like being treated this way.

Frankly, I don't make enough money on this book that if I told them to stuff it (just for ebook—they'd have to continue paying me my other royalties), I wouldn't be losing that much … what do you think?

This is a very slippery issue, for a number of reasons:

Contract language may be ambiguous as to who holds rights, and the language may be interpreted differently (there is little legal precedent to refer to in these situations)

Who retains e-book rights—author or publisher—is a controversial issue

Who holds rights to the text versus images may be different

Who holds e-book rights based on territory can be even more confusing

It's also a little tricky for me personally because I'm familiar with conventional language in most U.S. publishing contracts, and I don't know what differences there may be in the UK market. However, I believe there are still fundamental questions that apply regardless. (Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer and this is not professional legal advice.)

What, if anything, does your contract say about e-rights? If e-rights are not mentioned at all, it is difficult to see how your publisher could exploit them without your permission. How could they even set an e-book royalty percentage without a contract addendum? Find the contract and look for the language "rights to the text"—does this extend to all mediums and formats, or all means of delivery, storage, and reproduction? If not, you likely retain these rights if we're talking about a typical royalty contract (e.g., you did not agree to a work-for-hire arrangement).

Who owns rights to the images? This is a bind for many publishers who don't have the time and resources to go back and secure electronic rights to images used in print books. This issue is explored further by Emily Williams at Digital Book World, in Image Rights Slow Transition From Print to Ebook. A must-read for any author of illustrated books!

What territorial rights do they have? The answer to this question may be different for the text versus the images (creating another bind!). Do they have world rights to all of it, for all versions/editions?

My questions help structure an approach to determining an answer, yet that answer will probably not be 100% tight. Even if the contract seems to favor you—e.g., if it doesn't mention e-rights—a publisher might still claim they hold those rights, even if they can't exploit them (if you fail to agree to a contract addendum). The publisher may also feel emboldened because you don't have an agent.

Here's a quick summary of what's been argued and said up until now (mostly from the U.S.).

Controversy Surrounding This Issue

The latest controversy involves Open Road Media, an independent e-book publisher, which primarily publishes e-editions of traditionally published books where the author/agent has kept the e-rights. Publishing analyst Mike Shatzkin once said of Open Road, "[it's] exploiting the combination of old contracts that are ambiguous about ebook rights and the big trade houses' reluctance to go beyond a 25% of net receipts royalty on ebook sales to make high-profile ebook captures." HarperCollins is now suing Open Road because of its publication of a children's book that was originally signed in 1971. (See Publishers Weekly article here, plus illuminating comments by agent Robert Gottlieb.) Apparently, the contract in question gives Harper the right to be the exclusive publisher of the work, "in book form," including via "computer, computer-stored, mechanical or other electronic means now known or hereafter invented."

Random House also tried suing an independent e-book publisher, for very similar reasons to HarperCollins, in the Rosetta Stone case. Agent Robert Gottlieb references this case and comments (in the same PW article mentioned above): "The claim H/C is making that 'book form' covers electronic books does not hold water in my view. As an example if a publisher bought book rights and did not specifically have mass market or trade books listed in the agreement, could a publisher then say they still had the rights because they are covered by 'book form'? Normally publishing agreements are specific as to what a publisher has and doesn't have. If it is not stated in the agreement normally it is then a reserved right to the author." He then adds, "If such language truly covered ebooks there would be no reason today for publisher to specifically state that ebooks are covered in the agreements they are making with authors." Here's a viewpoint from agent Richard Curtis, who notes that publishers like Random and Harper typically view e-book rights as theirs to exploit if that language I cited in the first bullet point above is in the contract.

In 2010, agent Andrew Wylie (based in the UK) threatened to make an exclusive deal with Amazon for e-book rights on behalf of some very notable authors. He eventually backed away from this, but his position was clear (at least based on the contract language he negotiated): "Backlist digital rights were not conveyed to publishers, and so there's an opportunity to do something with those rights." Here's yet another thoughtful analysis of the situation by agent Richard Curtis.

For an in-depth legal perspective on the issue, I point you to CopyLaw's fine post (not that they offer any clearer answers!): Who Controls eBook Rights? from December 2011.

Most agents would say: If the rights are not clear in the contract, then the publisher is obligated to draw up a new and fair deal to cover those rights. It appears that's what your publisher is doing now, although the terms aren't very favorable for you.

I did find a 2010 article in the Guardian that indicates UK authors are being offered less favorable royalty rates than their U.S. counterparts. While 25% is a typical royalty rate for traditionally published e-books in the U.S., UK authors are struggling to get there—and sometimes this prevents any e-book editions from being released (due to lack of agreement between author and publisher).

Quick side note for all readers: If rights have reverted to you (if your book has gone out of print, which typically triggers a reversion of rights), then you have no need to worry. Rights should be yours to exploit!

I'd like to open up this issue to my readers—especially any agents who are reading this and have insight or experience—although I know it's difficult or impossible to say anything without seeing the contract.

January 10, 2012

How "Literary" and "Entrepreneur" Are Becoming Intertwined

Today's interview is brought to us by the wonderful novelist and humorist, John Warner.

Odds are, if you care about writing, reading, or books, you've run across Brad Listi. He's the author of a well-received novel, Attention. Deficit. Disorder; the founder and publisher of literary website The Nervous Breakdown (and its associated publishing imprint); and has recently added the title of "podcaster" to his resume with the launch of Other People with Brad Listi, which already counts Steve Almond, Emma Straub, Darrin Strauss, and Dana Spiotta among his guests. I was recently interviewed by him, and came away wondering how he's managing to juggle all these roles, so I took the opportunity to turn the tables and ask him a few questions.

When I think of Brad Listi, I think, "literary entrepreneur." Which comes first for you: the "literary," or the "entrepreneur"?

The literary. I consider myself a writer first. The rest of this stuff wouldn't be happening were it not for that fact. But it's also true that the two are increasingly intertwined, and that my "entrepreneurial" activities dominate a lot of my time these days. Initially the dream was to avoid the entrepreneurial stuff, to go write books and make good money and not have to worry about the rest. A small handful of authors seem to have that life, or some semblance of it. The overwhelming majority doesn't. To be exclusively "literary" is, to my eye, a rare occurrence.

Right now I don't have that option. Maybe someday I will. But even if I did, I'm not sure I would take it. What I've found over the years is that I don't like to work exclusively on one thing, or exclusively on my own behalf. That's not how I'm wired. And I mean, don't get me wrong: I love to write. It's a grind, but I love it. And I definitely have that component to my personality. But I also like to work with other people, and on behalf of other people. I don't want my work life to be exclusively about me and my books and my brain and my name. I start to feel suffocated by that after a while.

The work I've been doing on the entrepreneurial side of the equation feels in some ways accidental—The Nervous Breakdown, TNB Books, and the podcast, Other People. I kind of stumbled into a lot of this stuff, responding to shifts in publishing and changes in technology, and so on. Trying to wrap my head around the consequences of it all. Trying to be proactive and experimental and, I hope, a little bit helpful. The optimist in me feels like we're living in a rare time. Publishing is a massive, multi-billion-dollar business, and it's going through a revolution. I don't think that's an overstatement. The rules are being rewritten, nobody knows exactly what's going to happen, and authors have an opportunity to affect the process. I like that part of it, maybe more so than others. I find it interesting.

With all of your different roles (editor, podcaster, writer, father of a small child) requiring what I'm imagining is some serious juggling, what's the typical Brad Listi work day?

I work from nine to five, or thereabouts. And then I'll hang out with my daughter for a couple of hours. And then I'll usually do a few more hours at the computer after she goes to bed. It's not uncommon for me to work until midnight, or a little after. And I usually work six days a week. (My wife is an extremely patient woman.) It's not entirely ideal, but I really like what I do. If I didn't, I don't think I could hack it.

Why expand into podcasting? What's missing that you think "Other People" is able to provide?

Well, I'm a big radio nerd, for starters. I'm a huge Howard Stern fan. He's probably the root of it all. I think he's criminally misunderstood by a lot of people, many of whom have never really listened to him. And I'm a podcast nerd, too. Everything from Fresh Air to The Moth to Times Talks to Charlie Rose to WTF to This American Life to New Yorker podcasts, to you name it. I listen to a ton of this stuff and really love the medium. And I was having trouble finding a book-related show that would do what I wanted it to do. Either the conversations were too short, or too dry, or too lit-crit oriented, or too self-serious, or whatever. I wanted a show that focused on writers as people, one that really humanized them. Who they are. Where they come from. What their shitty day job is, or was. Why they write. How they stay motivated. And so on. I wanted something a bit looser, more informal, more candid and spontaneous and funny. And after searching for a while and not being able to find it, I decided to do it on my own.

And I also think the show is a response to my own existence, much of which is spent online. Writers in general spend an absurd amount of time at their keyboards, and on the Internet, and in many ways we have a greater degree of connectivity and community than ever before. But of course this connectivity is usually digital, and the community is often two-dimensional. You know people superficially by their avatar photos, or by their Twitter feeds or status updates. I get a little bit exhausted by that after a while. And the podcast, I think, was born of this fatigue. I wanted to talk to people. I wanted to hear some voices.

The podcast sounds sort of effortless as I listen to it, but I'm imaging that's not the case.

(Laughs.) No, that's not the case. I wish that were the case. I spend a lot of time on it. And the more listeners that I have, the more worked up I get about execution. All of a sudden there's an audience. I don't want to fuck it up. I don't want to bore people or ramble on interminably or say something idiotic. I really sweat over this stuff. Just ask my wife.

And then of course there's the learning curve. I'm still pretty new to the medium and figuring it out as I go. You make your mistakes and try to learn from them as quickly as possible. The hardest part is listening to my own shows, which I force myself to do. It's painful but necessary, comparable to the revision process in writing. You have to do it if you want to improve.

It seems that, without a doubt, we're in the midst of revolutionary change when it comes to writing and publishing. As a guy who's plugged in to the leading edge, what do you see as the future path for people who want to live a life of writing?

Oh, god. Well … it never hurts to be super-talented and prolific, with great commercial instincts and insanely good connections. And it's probably a good idea to become an expert at something. Find a niche. Write a blog regularly. Build a community around your work. Interact with that community. Feed the stray cats. And if you're incredibly charming and have a good headshot and make friends easily, both in person and online, that'll help, too. And if you have good marketing instincts and a talent for cyber-publicity stunts, that can potentially be useful as well.

Otherwise, what can you say? It's a very competitive environment. There are a lot of good writers out there, and beyond that, there's an insane amount of stimuli vying for the attention of the general public. Authors are competing against movies, television, smartphones, video games, radio, social media, the Internet, you name it. And everything seems to be atomizing. I talked about this on a recent episode of the podcast, how all forms of media seem to be splintering in a million different directions. It's remarkable. And a little unnerving.

It feels like we're entering a new media landscape where the barrier to entry is essentially nonexistent. Almost anyone can make a TV show, for example, and play it on the Internet to a possible worldwide audience. And the Internet is soon going to be integrated with your television, if it isn't already. Camera technology is getting better and better—and cheaper. And so now anyone can make a movie pretty affordably (relatively speaking) and edit it on their laptop and make it available to people to watch on their flatscreens or iPads or smartphones or whatever. And almost anyone can record an album and sell it on iTunes. And almost anyone can write a book and publish it and distribute it globally and run their own imprint and create their own magazine. And so on. It's crazy.

All of the various media worlds seem to be reconfiguring themselves in dramatic fashion, simultaneously. Production and distribution have been democratized. It's a massive reshuffling of the deck. And of course the flipside of this equation is that readers and viewers and listeners are provided with an increasingly insane amount of choices. Capturing market share and building a following in this kind of environment is difficult.

As far as publishing goes, I don't think there are any easy answers or magic bullets. On the one hand, there are a lot of things about the digital revolution that are promising. It shifts a lot of power to the author and enables us to make more money on a per-sale basis. This is a good thing—potentially a very good thing insofar as making a living goes. But then there's still the issue of marketing and making actual sales. And as far as that goes, my view is that word-of-mouth trumps all. Same as it ever was. Nothing is more important when it comes to selling books. So first and foremost, you have to be really, really good. And then secondly, you have to be really, really lucky; you have to catch that magical cosmic wave that certain books and authors seem to catch as a function of timing and the mood of the collective subconscious. And thirdly, you have to be proactive and effective in letting people know about your work.

Otherwise, if you're an artist, I think you just keep working. You say fuck it and forget about all the rest. You focus on what you do, and you try to do it really well. You make the necessary sacrifices. You follow your nose, and you try things. You experiment. You trust your instincts. You stay awake to changing business realities. You take chances and maintain a willingness to fail. You keep an open mind.

And I mean, despite all the flux and chaos out there, at the core of it nothing much has changed: if you're a writer, you can't do it to become rich or famous. That's a fool's errand. The only reason to go through the agonies and ecstasies of writing a book is because you have no other choice. You do it because you love to do it, and you can't not do it, and you do it because you have something that you urgently need to say. Otherwise you probably shouldn't do it at all.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to check out this Q&A with John Warner.

January 9, 2012

A Model for Crowdsourced Publishing

Today's guest post is by Scott Vankirk (@mightyscoo).

As much as we (aspiring authors) tend to get joy and satisfaction vilifying The System, the problem is not really the publishing houses nor the agents that feed them, nor their unhelpful rejection letters. The problem is the sheer number of us. Just about everyone has something to say, a story to tell. Even if you only count the good ones, like mine  , there are simply not enough publishing houses, or agents, to handle them. Traditional publishing is the dam between the great lake of writers and the vast ocean of readers.

, there are simply not enough publishing houses, or agents, to handle them. Traditional publishing is the dam between the great lake of writers and the vast ocean of readers.

With the advent of real opportunities in the self publishing world (see John Locke or Amanda Hawking or Joe Konrath), that dam is starting to crack. When it finally goes completely, there will be a deluge of books flooding the reader ocean. Pushing the metaphor to its breaking point, we are going get the standard bass, salmon and trout—even the ones stuck behind the dam before—but we will also get the catfish (some people like them), the crayfish (same), the bottom slugs (ick), insect larvae, bits of branches (huh?), and rocks. Don't forget the mud: this dam break is going to muddy the waters something fierce. That's going to hamper our fishing for quite a while. If you can't tell if a book is a bass or a rock, you risk going hungry. So the question is, how do you clear away the mud and bring the good fish to the top where they are easy pickings?

The answer is crowdsourced publishing.

OK, so back to our tortured metaphor … no? OK, we will drop the metaphor. Reality is metaphoric enough all by itself. Wikipedia is the original, and the most stunningly successful, crowdsourced application to date. Its store of knowledge is staggering. It's even got a great definition of crowdsourcing.

So how would this crowdsourced publishing work?

You would want it to be open and transparent.

You would design it to be self supporting.

You would make it as inclusive as possible. There should be tools available that will allow any of the hundreds of existing reading/writing/publishing sites to become affiliates with the ability to participate in the crowd.

The goal of this site would be threefold:

Publish and sell high-quality books

Create a reviewing and classifying system

Let people who help make a little bit of money

This site would offer membership to anyone who wants one. Any member of this site would have an opportunity to participate in the publishing pipeline in one or more roles. The goal of all these roles is to get a story published. Each person that is involved with a book project will receive some of the revenues from the sale of these books. The roles and their percentage of the revenues from a sale might look something like this:

Writer: 65%

Website: 15% (to run site, promote books, print books)

Critiquer/Collaborator: up to 20% (agreed beforehand, and writer can also grant from their own percentage)

Editor: up to 20% (agreed beforehand, and writer can also grant from their own percentage)

Each member of the website would register for the roles they are willing to perform. Authors would put together a team to perform all the necessary roles in the publishing process. All members of the team gain reputation points based upon book sales and upon grades awarded by other members of the team.

As people perform their roles, their reputation increases or decreases accordingly. This means that someone can have a high reputation as a critiquer but a low reputation as an editor. The higher the reputation, the more in-demand a person will become. As time goes on, people will get better and better fees for a book based upon the publishing team who worked on it.

A vital function for the site would be to make it easy to find books. People should be able to browse by author, editor, reviews, reviewers, ratings, genre, overall sales and by keywords.

Of course, the devil is in the details, but something along these lines might help increase the quality of self-published books. In addition, it allows everyone with a passion for it to possibly make a little cash on the side. It scales nicely, too. The dam is gone, the murk is cleared and the good fish can be easily spotted.

What do you think? Is it worth trying? Any glaring holes? Let's discuss in the comments.

Scott VanKirk is a serial entrepreneur. He spent two decades on the bleeding edge of computer programming as a consulting engineer. During that time, he developed online gaming software, websites and commodities trading systems. For the last five years, Scott ran a five-million dollar per year solar energy company, selling, designing, and installing photovoltaic or solar thermal systems. Scott has written six novels in the science fiction, children's fantasy and urban fantasy genres.

Scott VanKirk is a serial entrepreneur. He spent two decades on the bleeding edge of computer programming as a consulting engineer. During that time, he developed online gaming software, websites and commodities trading systems. For the last five years, Scott ran a five-million dollar per year solar energy company, selling, designing, and installing photovoltaic or solar thermal systems. Scott has written six novels in the science fiction, children's fantasy and urban fantasy genres.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers