Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 187

July 13, 2012

Should You Self-Host Your Blog or Website?

Recently I was asked why authors should self-host their own blog or website.

First, what does self-host mean?

It means that you don’t use a free service to run your blog or website. The most popular free services are Blogger and WordPress.com. What confuses a lot of people is that you can run a website or blog that is based on the WordPress system, but is self-hosted. (That describes THIS site.)

So what are the big reasons NOT to use a free service?

Free services limit the functionality and options for your site.

Free services limit how much you can customize the look and feel of the site.

Sometimes you are working on proprietary systems that could be abandoned at any time. They might not be supported in the way you need them to be.

Free services might not offer the kind of metrics and analytics you need to see what’s working.

It’s more difficult to make money from a free service (it can be impossible to add eCommerce/shopping cart functionality or to run ads)

When you’re self-hosted, you really own your website and have full control. And for serious, professional authors, who are building a longterm online presence, that’s what I recommend. (If you are doing a very short-lived site, or if you’re just “fooling around,” then yes, do use a free service!)

You can read more of my opinion at Roz Morris’s blog. You can also get advice from well-known writers who do NOT recommend self-hosting.

July 10, 2012

The Reader Must Want to Know What Happens Next

Today’s post is excerpted from Wired for Story by Lisa Cron, just released from Ten Speed Press.

We think in story. It’s hardwired in our brain. It’s how we make strategic sense of the otherwise overwhelming world around us. Simply put, the brain constantly seeks meaning from all the input thrown at it, yanks out what’s important for our survival on a need-to-know basis, and tells us a story about it, based on what it knows of our past experience with it, how we feel about it, and how it might affect us. Rather than recording everything on a first-come, first-served basis, our brain casts us as “the protagonist” and then edits our experience with cinema-like precision, creating logical interrelations, mapping connections between memories, ideas, and events for future reference.

Story is the language of experience, whether it’s ours, someone else’s, or that of fictional characters. Other people’s stories are as important as the stories we tell ourselves. Because if all we ever had to go on was our own experience, we wouldn’t make it out of onesies.

So, What Is a Story?

Contrary to what many people think, a story is not just something that happens. If that were true, we could all cancel the cable, lug our Barcaloungers onto the front lawn, and be utterly entertained, 24/7, just watching the world go by. It would be idyllic for about ten minutes. Then we’d be climbing the walls, if only there were walls on the front lawn.

A story isn’t simply something that happens to someone, either. If it were, we’d be utterly enthralled reading a stranger’s earnestly rendered, heartfelt journal chronicling every trip she took to the grocery store, ever—and we’re not.

A story isn’t even something dramatic that happens to someone. Would you stay up all night reading about how bloodthirsty Gladiator A chased cutthroat Gladiator B around a dusty old arena for two hundred pages? I’m thinking no.

So what is a story? A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result. Breaking it down in the soothingly familiar parlance of the writing world, this translates to

“What happens” is the plot.

“Someone” is the protagonist.

The “goal” is what’s known as the story question.

And “how he or she changes” is what the story itself is actually about.

As counterintuitive as it may sound, a story is not about the plot or even what happens in it. Stories are about how we, rather than the world around us, change. They grab us only when they allow us to experience how it would feel to navigate the plot. Thus story, as we’ll see throughout, is an internal journey, not an external one.

All the elements of a story are anchored in this very simple premise, and they work in unison to create what appears to the reader as reality, only sharper, clearer, and far more entertaining, because stories do what our cognitive unconscious does: filter out everything that would distract us from the situation at hand. In fact, stories do it better, because while in real life it’s nearly impossible to filter out all the annoying little interruptions—like leaky faucets, dithering bosses, and cranky spouses—a story can tune them out entirely as it focuses in on the task at hand: What does your protagonist have to confront in order to solve the problem you’ve so cleverly set up for her? And that problem is what the reader is going to be hunting for from the get-go, because it’s going to define everything that happens from the first sentence on.

Questions to ask yourself

Do we know whose story it is? There must be someone through whose eyes we are viewing the world we’ve been plunked into—aka the protagonist. Think of your protagonist as the reader’s surrogate in the world that you, the writer, are creating.

Is something happening, beginning on the first page? Don’t just set the stage for later conflict. Jump right in with something that will affect the protagonist and so make the reader hungry to find out what the consequence will be. After all, unless something is already happening, how can we want to know what happens next?

Is there conflict in what’s happening? Will the conflict have a direct impact on the protagonist’s quest, even though your reader might not yet know what that quest is?

Is something at stake on the first page? And, as important, is your reader aware of what it is?

Is there a sense that “all is not as it seems”? This is especially important if the protagonist isn’t introduced in the first few pages, in which case it pays to ask: Is there a growing sense of focused foreboding that’ll keep the reader hooked until the protagonist appears in the not-too-distant future?

Can we glimpse enough of the “big picture” to have that all-important yardstick? It’s the “big picture” that gives readers perspective and conveys the point of each scene, enabling them to add things up. If we don’t know where the story is going, how can we tell if it’s moving at all?

If you enjoyed this excerpt, then you’ll love Wired for Story . Chapters cover the basics elements of fiction, such as protagonist development, conflict development, and story structure. Click here to read more about the book at Amazon.

Reprinted with permission from Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence by Lisa Cron © 2012. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group.

July 6, 2012

Why Write When Others Write So Much Better?

Every writer I know can identify with the following:

I was only halfway through Stuart Dybek’s I Sailed with Magellan when I decided I should just give up on writing altogether; that the intimacy he achieves with childhood and adolescence was more than I could ever imagine accomplishing, and I wanted to leave it to him, a far more lyric, braver writer than I would ever be. At these humbling moments, I remember advice I received from Dan Chaon while studying fiction at Oberlin.

That’s from “Becoming a Mapbuilder” by Danielle Lazarin (@d_lazarin). The advice she received from Chaon? There’s a very specific world that only you can write about. Click here to read her entire column over at Glimmer Train.

You can also find the following at their new bulletin:

Oh, The Mistakes I’ve Made and The Wonders to Howl About by Stefanie Freele, which includes 4 mistakes and 4 magnificent things that surprised her about the writing and publishing world.

Looking Back by Andrew Porter, on not being quick to discount your early work.

Click here to view the entire Glimmer Train bulletin.

July 3, 2012

EXTRA ETHER: eBooks Gone in 5 Years?

The distinction between “the Internet” and “books” is arbitrary, and will disappear in 5 years. Start adjusting now.

In the words of John McEnroe, you cannot be serious. Haven’t we all just staggered over to the ebook reality, gotten down with our digital selves, and tried to ease away from those visions of dustcovers dancing at our launch parties?

And now Hugh McGuire is here to tell us ebooks aren’t going to make it, either? Well, yeah, in a way. Despite what may seem like odd timing. After all, we know that eBook Revenues Topped Hardcover in the first quarter, per the Association of American Publishers, as Jason Boog at GalleyCat has dutifully reported.

It sounds like ebooks have taken over, stand well back, and anybody saying otherwise is just…talking TEDx-y. That’s where McGuire said it. TEDx Montreal.

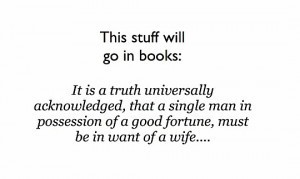

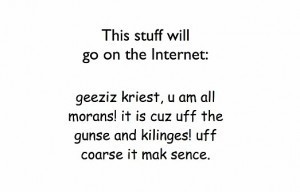

There’s a very big distinction that people make, that certain kinds of words and sentences go into books…and other kinds of words and sentences go into the Internet.

McGuire’s idea of the distinction people make was borne out by a tweet from Guardian columnist and author Damien Walter, who wrote:

Books are researched, written, edited, published, marketed…and hence paid for. The Internet is ego noise, hence free.

Hugh McGuire

McGuire, of course, is someone we know.

He’s the creator not only of the PressBooks production tool, which “makes it easy for authors and editorial teams to generate clean, well-formatted books in multiple outputs,” but also of several approaches to audiobooks. Something of a serial startup guy.

He co-edited with Brian O’Leary the seminal Book: A Futurist’s Manifesto, which has enough meaningful, thought-provoking essays in it to keep you muttering to yourself from the tiki bar back to the pool for the rest of the summer. Have a look if you haven’t seen its free online version.

But here’s McGuire, going on at TEDx Montreal:

It’s worth asking why it is that — given that Project Gutenberg has been around since the earliest days of the Internet — we haven’t seen a large embrace of reading on screens until very recently.

From Hugh McGuire’s TEDx Montreal presentation

Why is there a widely perceived assumption that more important work goes into books?

Why are only “ego noise” and other less worthy writings considered right for the Net?

McGuire points out that both Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s iPhone arrived in 2007. He says he read War and Peace on his iPhone. (There could be a battery-life advertisement in that, I’m sure.)

From Hugh McGuire’s TEDx Montreal presentation

Despite the burgeoning expansion of ebooks, however — and their emblematic status as the icon of the digital revolution — McGuire points out that ebooks are a lot more similar to web sites than they are to traditional books.

The catch?

Publishers are deathly afraid of the Internet. And they have very good reason to be, because the Internet is famous for gobbling up business models and spitting out total chaos.

The look and feel of ebooks hasn’t been too scary yet, he says, “because ebooks looked pretty similar to books, in terms of the structure of the business and what we can do with them.”

And this is where McGuire heads straight for your comfort zone:

It’s a problem because in order to get this similarity with the past, we’ve ended up constraining ebooks and making them look a lot more like print books and a lot less like the Internet.

Linking out, for example, McGuire says, and other fundamental forms of online interaction that we might expect on the web aren’t normally supported in ebooks:

You can’t link to a canonical version of an ebook. You can’t link to a specific chapter or a specific page. You usually can’t copy and paste. You can’t even leave a comment in a central place.

And, as we know, there are louder and louder comments to the effect that book apps aren’t making as much sense as we thought they would because they’re expensive, closed systems by comparison to HTML5.

McGuire:

So this poses a question to all of you as readers: Would you have more value if books were available in print and ebooks and a web version, or if you just had print and ebooks?

It’s clear what McGuire’s choice is. He offers a couple of strong examples of deeply interactive projects. One is the YouVersion interactive Bible site. Another is one he describes as an extensively structured online rendering of the 1912 journal of Robert Scott’s expedition to the South Pole, “a beautiful web experience,” each element of the journey tied to Google Maps.

What you won’t get from this 13-minute talk is the answer.

And that’s the reason to watch this video. That’s the point we all need to get now: there is no answer.

It’s human nature to think the publishing industry’s upheaval is deadheading us into a stable, static, dependable solution to all the business’ confusions and upheavals. Surely this will calm down eventually. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life. Right?

Wrong. For some time now, Virginia Quarterly Review’s Jane Friedman has been trying to wean readers away from the standard idea of “The Book” as the inevitable goal. Here she is, in a piece from October, asking “What is your killer medium?”:

The book is often assumed to be the most authoritative and important medium, but that’s only because we’ve all been led to believe that (through a culture that has created The Myth about the author as authority). It’s a Myth, neither good nor bad. Just a belief system that, increasingly, we’re all moving away from.

The new norm may be no norm.

And for those already exhausted, already reeling from change and surprise and so much confusion and contradiction, the message is all the more important. Look for some peace with this. “Start adjusting now,” as McGuire puts it. Because holding out for a final answer, Regis, might be the worst mistake you could make.

McGuire:

The important thing is that we don’t know. We don’t know because the Internet is this wide-open place where amazing things happen when we start to put data on it. We never really could have imagined what email did to mail, what Twitter did to conversation.

McGuire suggests we think about books “as great data sets that could be explored in new ways by people once they were opened up on the web.” Because:

The future of what we do, once we start to put books into this connected/network world is totally open, and that’s a very exciting thing for people who love books and who love the web.

Join us Thursday here at JaneFriedman.com for Writing on the Ether, the Day After the Fourth edition, presented by Ether sponsor Will Entrekin and his Exciting Press book, The Prodigal Hour. Save us a sparkler, will you?

June 27, 2012

Why Self-Publishing Is a Tragic Term

The Birds Tree by ploop26 / DeviantArt

Today’s guest post is by Ed Cyzewski. You may recall him from his previous post here, When Self-Publishing Is More Useful as a Marketing Tool.

My friend Shawn recently released a book that shares his journey into full-time writing. It involves a failed small business, $50,000 in debt, a difficult return to his parents’ basement, and a plan to rebuild his life through writing. It’s a unique, inspiring story, but that’s not what really caught my attention about his book.

Shawn invited nine colleagues to share their own stories about writing full time. I shared how I advertise my freelance blogging and editing services. I’m sure there are plenty of books out there that include short stories and case studies, but Shawn actually wove each contributor’s essay into his own story, explaining how each of us provided ideas for his work.

Technically speaking, Shawn self-published this book. However, his community-based approach provides lessons for both commercial publishing and self-publishing.

Self-Publishing Doesn’t Have to Be Lonely

Writers are already cooped up in corners of their bedrooms or in back corners of cafes. Must the publishing process add another layer of isolation?

Many authors have wisely moved away from the term “self-publishing.” I’ve seen words like “independent” or “indie” publishing tossed around. They help characterize this kind of publishing as an independent business model, not necessarily a solitary pursuit. The very use of the word “self” belies a tragic individualism and reliance on “self” in publishing today. To speak of “self-publishing” is a linguistic mistake that could hint that publishing is all up to you.

There’s No Such Thing as Self-Marketing

I am one of many nonfiction authors whose nose has been rubbed in the word “platform” long enough to realize that I can’t sell books on my own. Nonfiction authors especially need tribes, subscribers, followers, friends, pins, backers, and enough Facebook shares to convince hipsters that your writing is “so over.”

People have to decide that our work is valuable and share it, buy it, or preferably do both.

Shawn didn’t just build a community in order to market his book. He built a community around creating a book—including the writing and cover design. When it came time to promote his project, he had a community of writers who were eager to share his creation because we all shared a part in it.

Is Community Publishing for You?

Shawn’s book is one of many projects that have prompted me to rethink my future publishing plans. While I’m already pitching several book projects with a variety of co-authors, I’m beginning to explore what “community publishing” could look like.

I’ve already worked hard to build a community of writing colleagues through blogs, social media, and writing conferences, and now I’m trying to match these colleagues with my own community publishing projects. One particular proposal involves a series of essays about leaving and returning to the church. My own story creates the framework for the book, but brief essays by my colleagues add depth and insight that I could never offer on my own.

I’m still hoping to publish these community projects commercially, but the thought of self-publishing them isn’t quite so daunting since I wouldn’t be on my own throughout the publishing process.

The word self-publishing tells a lie of sorts—at least, it’s a lie for most of us. It hints that you can publish a book successfully on your own. For most of us, that simply isn’t true. For the great majority of us, self-publishing a book on our own will also be lonely and unpleasant.

I’ve seen authors and publishers produce incredible books with community-driven models. While I’ll still pitch some projects that are solely my own, my long-term publishing plans revolve around sharing my work with a community of writers and rising together.

If community publishing strikes you as too intimidating, keep in mind that many bloggers already know how community publishing works. Bloggers who host guest posts make community publishing work. In fact, many of the most popular blogs accept guest posts.

Perhaps community publishing is a passing fad, but I’m betting that it provides an ideal way forward for writers who are tired of staring at the wall in a café. If it flops, at least I’ll have a few friends willing to buy me a cup of tea so we can talk about our next project.

June 22, 2012

I’m Out of Advice (for Now)

Today is my last post for Writer Unboxed, where I’ve been a contributor since December 2009. It’s called:

I Have No More Advice Left to Give

The post serves as a public announcement that I’m pulling back from my blogging to focus on other projects I’d like to pursue. This decision is also influenced by my new position at the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Often a big life change offers a moment to pause and reflect on everything you do—and what things you ought to stop doing. And when I realized I had nothing truly new to say to writers about publishing (only new ways of saying the same thing), I decided now is the right time to modify where I devote my writing energy.

This website and blog will continue much as before. Porter Anderson’s Writing on the Ether column will continue; I’ll still run book excerpts related to writing and career; I’ll still accept guest posts from people who I think have something special or valuable to offer.

And I’ll jump in from time to time when I have something I feel is truly meaningful to share. You just might not find something posted here 5 days a week, and frankly, that’s probably a good thing for everyone. Use the time to write, read, or be creative.

June 20, 2012

Are You Making This Marketing Mistake?

Today’s guest post is from Jason Kong.

When your goal is to sell ideas, books, or yourself, it’s easy to think that the key is to target strangers. People unfamiliar with your writing seems like the best opportunity to reach new readers.

The problem is that even if you’re just looking to create awareness, talking to the masses doesn’t work very well. Most of the time you’re ignored. Even when you’re not, the attention you get doesn’t translate into anything meaningful. No wonder many writers loathe marketing.

Luckily, there’s a better alternative.

How an artist raised over a million dollars in 32 days

Amanda Palmer is a musician. Just last month, she held a Kickstarter campaign to fund her next record and tour.

In just over a month, nearly 25,000 people made a contribution. The seven-figure raised exceeded her goal by over ten-fold.

What made this such a successful fundraiser? You have to wonder if Palmer is a marketing genius in addition to being a rock star.

Checking out her Kickstarter page provides the insight.

What you’ll find is an in-depth description of what the contributions would support—plus pictures, video, and the different rewards associated with each pledge level. It’s a lot to take in, and completely uninteresting if you didn’t like Amanda Palmer already. Which is exactly the point.

This wasn’t a campaign for strangers. It was for her fans.

Creating a tidal wave of success

In a revealing article written by Palmer herself, she explains her approach to the project. Some of the interesting takeaways are:

She focuses obsessively on her fans and depends on them.

It wasn’t a marketing trick. She connects with her supporters because it brings joy to both sides.

Her success didn’t happen overnight. Years of hard work led to big results.

Palmer’s fans trust her because she earned it.

Palmer makes it all about her fans, the ones who care and appreciate her work. In return, they support her with money and positive word of mouth. Her following grows because of relationships developed over time. She clearly enjoys herself, and so do her fans.

What this story means for you

Okay, you’re not a musician and you don’t have Amanda Palmer’s platform. But putting an emphasis on your fans can lead you on a similar path.

Ask yourself:

Do you know who your fans are?

Are you showing enough love and gratitude?

Is it easy for them to connect with you and each other?

The essence of good marketing isn’t simply awareness or selling. It’s also about focusing on the people who matter.

Your fans are waiting.

June 17, 2012

How Dads Influenced Some Famous Writers

My dad once told me I could do or be anything I wanted.

Apparently that’s the same thing author Patricia Bosworth was told by her dad. Dads seem to enjoy sharing this advice with their daughters.

In honor of Father’s Day, the folks at Open Road Media have produced a video where famous writers discuss how their dads influenced them. Click here to view if the video is not embedded above.

Other Father’s Day tributes from Open Road:

My Famous Father: the children of famous authors speak

Archival photos: authors and dads

June 15, 2012

Trademark Is Not a Verb: Guidelines From a Trademark Lawyer

Today’s guest post is from lawyer Brad Frazer.

I bet I get one call or e-mail per day from someone wishing to “trademark” something. “Hey, Brad,” they will say, “I want to trademark my new logo. Can you help me with that?”

As has become my new mantra, I explain to them that trademark is not a verb. It is a noun. Depending on my mood, I will sometimes then go on to discuss common-law trademarks versus trademark registration, and the “Circle R” symbol versus the small superscript “TM.”

The true nature of trademarks is, admittedly, confusing, especially when they are so often confused with copyrights and patents—two completely different forms of intellectual property protection.

In a broad sense, “intellectual property,” as contrasted with real property (dirt) and personal property (cars and computers), has four main subgroups:

Patents. Protects inventions and processes.

Copyrights. Protects things such as books, movies, and photographs.

Trade secrets. A secret device or technique used by a company in manufacturing its products.

Trademarks. A broad category of intellectual property that performs a commercial identification function—they tell you about the source of the good or service you are consuming. You know that a Big Mac hamburger comes from McDonald’s, that a shoe with a swoosh on it comes from Nike, and that insurance being sold by a gecko comes from GEICO.

When I finished the first draft of my novel The Cure, I asked a beta reader to look it over. Her reaction was favorable, but I remember her asking me why there were so many trademarks in it. Her point was that I, as a trademark lawyer, had gone overboard taking care to identify goods and services referenced in the book by their trademark: one character sported a Rolex®-brand watch, another wore Gucci® shoes. I put the circle R symbols right there in the manuscript.

(By the way, circle R is used with trademarks that have been registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. TM is for those that have not.)

Those symbols and most of the trademarks were all removed in subsequent revisions of my now-published novel, but the point stuck with me. There is a feeling that one must somehow obtain permission, genuflect or pay money or something when one uses a third-party trademark in a manuscript.

For example, assume that you wrote this sentence: “Marjorie picked up her Marlboros® and slid one from the pack, then flicked her Bic® lighter and inhaled, silently thanking Blue Cross® for her excellent health insurance.”

Stylistic conventions aside, do you need permission from Marlboro, Bic and Blue Cross to use their trademarks in this manner? Must you use the “Circle R” symbol, or risk getting sued?

The answer in both cases is, as a general rule, no. The only time a third-party can force you to use the Circle R or TM symbols is if you have a contract of some kind with them that compels you to do so. Trademarks are a form of commercial identification and only gain life and viability when used in a commercial context to sell goods or services. (Now if we change the hypothetical and assume that the prose you wrote is part of a short story being used to sell Zippo lighters, then Bic might arguably have an objection!)

Same thing with band names (as opposed to “brand” names). A band name, e.g., “ZZ Top,” can function as a trademark, but as a general rule, you may use the name of a band in a manuscript as long as it is in a noncommercial context. Sometimes a client will ask if the fact they are selling the book for money means it is a commercial use, and the answer is no. Trademark law is concerned with the selling of related goods or services using trademarks in manner that will confuse consumers, and contextual use in a manuscript is not serving to sell competing services or goods (outside of our Zippo hypothetical).

But be careful with lyrics—lyrics are protected by copyright law, not trademark law, and so wholesale appropriation of lyrics into a manuscript may get you into hot water for copyright infringement, and the fact you are selling the book for money IS relevant in a copyright context!

Candidly, I have not found that using actual trademarks brings much life or verisimilitude to a manuscript, but if you choose to use them, and if you use them in a manner not designed to sell competing goods or services, neither permission nor marking (the Circle R and TM) should be required.

June 13, 2012

Video: Changes in Publishing & Self-Publishing

Some of you may have heard about the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), a new organization supporting self-published authors. I’m one of the advisors, along with Mark Coker (Smashwords), Joanna Penn (Creative Penn), and Victoria Strauss (SFWA), among other well-known publishing professionals.

I discuss reasons for moving to VQR, changes in publishing and self-publishing and what it means for authors—plus I pass on a top tip (hint: it’s to do with your blog).

Also covered:

Marrying business side and artistic side of writing

The creative and artistic potential of self-publishing today

The dangers of “irrational exuberance”

The need for self-publishers—and all writers—to develop their entrepreneurial skills

How the major challenge for publishing houses now is to see authors as equals.

If you don’t see the video embedded above, then click here to see on Vimeo.

If you’re interested in other interviews I’ve given (video, audio, text), click here to view the archives.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers