Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 182

November 7, 2012

A Framework for Thinking About Author Platform

Yesterday, I had the pleasure of participating in an online Google Hangout with the Bay Area Bloggers, hosted by Anne Hill and Suzanna Stinnet.

The conversation focused primarily on author platform. We discussed its evolution, its purpose in your career, and how you can decide what efforts are worth your time—plus the value of collaborating with other authors.

If you don’t see the video embedded above, click here to watch the 30-minute conversation at YouTube.

November 6, 2012

26 Questions on Writing & Publishing: My Answers on Reddit

Last Friday, I had the honor of spending a day with the Reddit writing community, where I participated in an AMA (Ask Me Anything). I answered such questions as:

Is self-epublishing being overblown?

Where can you find freelance editing and copyediting jobs?

What are some good conferences to meet agents in person?

How has agenting changed in the last decade?

Which publishers are responding in innovative ways to the digital revolution?

What are my favorite resources for authors?

And much, much more. Click here to read the complete Q&A. You don’t have to be a Reddit community member to read.

November 2, 2012

2 Critical Factors for Successful Stories

You can be a beautiful and gifted writer yet fail to craft a compelling narrative. Joshua Henkin, in the latest Glimmer Train bulletin, elucidates, in a memorable and striking way, how to check your work for two critical factors of a successful story:

For a story to work, there needs to be both consequence and agency, and one way to tell whether your story is succeeding in this regard is to ask yourself a couple of questions. First, type your scenes out on separate sheets of paper so that it’s possible to scramble them. Can you scramble them? You shouldn’t be able to. … If you can reorder them, then the odds are your story isn’t driven sufficiently by consequence. Second, ask yourself what would happen if you yanked your protagonist out of the story. If the only thing the story would lose was your protagonist’s observations … then the odds are there’s insufficient agency in your story.

Read Henkin’s entire piece at the Glimmer Train site.

Also, check out these other articles:

On achieving needed focus to start writing, from Maggie Shipstead

On the difference between short stories and novels, from David Ebenbach

On the risk and reward of writing what you know, from Natalie Sypolt

October 26, 2012

Do Publishers Need to Offer More Value to Authors?

Chatting with Kay Steinke at LitFlow (Berlin), 2012

Last month, I gave a 15-minute presentation in Berlin, Germany, called The Future of the Author-Publisher Relationship, as part of an innovative publishing think-tank event called LitFlow. To accompany my talk, I wrote a 2,500-word article that was posted on LitFlow’s website. You can read it here.

In a nutshell, I suggest that—given the changes happening in the industry—traditional publishers will need to be more author-focused in their operations by offering tools, community, and education to help authors be more successful, to everyone’s greater benefit. If publishers fail to do so, then authors, who have an increasing number of publishing options available to them, will depart for greener pastures. I pointed out that Amazon has a VP of author relations, and views the author like a second customer, but publishers have no such author-relations position or focus on authors as a community to be served. I recommended publishers create their own VPs of author relations and be more strategic in serving authors on a long-term, broad basis rather than on a title-by-title basis.

Unsurprisingly, I’ve seen a lot of public shares and comments about this piece from authors, but very little from those working inside New York publishing. Part of that is natural—I’m known mostly to authors and they follow me. The other part, though, is that my proposal is flawed, even laughable, if you’re part of the Big Six engine. Let me count the ways.

1. Publishers’ most important service to authors is undertaking the financial risk of their creative work.

If you sign a traditional deal with a Big Six house, you’ll receive an advance. But most authors (up to 80%) never see royalties; their books never earn out. That means most publishers pay more to authors than what prevailing royalty rates might indicate, though there are reports that advances are declining.

Still, publishers (and agents) by and large make it possible for authors to focus more on writing than the business. Even if authors don’t earn a living wage, most are not eager to shoulder the risk alone. Now, some might argue that e-publishing and digital distribution has greatly reduced financial risk for creative work—even driven it to zero. But there remains an opportunity cost. You’re not doing something else: you’re not spending time with loved ones, you’re not working another job, you’re not learning a new skill, etc. So, again, I think it’s reasonable to assume that most authors would like to be less exposed to risk.

I participated in a recent conversation where a publisher-insider asserted that Amazon KDP (and similar DIY e-publishing services, pick your favorite) offered nothing to authors, while taking 30-70 percent for offering that nothing. Point being: Amazon doesn’t lift a finger for KDP authors, for the quality of the work, or for the marketing and promotion of that specific work; they don’t do anything a traditional publisher would do. Amazon assumes no risk yet receives a nice cut, while the author is 100% exposed. All KDP authors could fail, but ultimately Amazon loses nothing, having offered nothing. They only gain.

Of course, this “nothing” that Amazon offers has been a pretty attractive nothing for authors rejected by traditional gatekeepers. This nothing provides authors an equal opportunity to play along with the big dogs at the biggest e-retailing storefront in the world. This nothing is earning authors some meaningful money, whereas 5 or 10 years ago, it would have been near impossible for an author to expect any results at all from an e-publishing or self-publishing effort. (Plus there are other ways that this “nothing” can be even better than what a traditional publisher provides, but I’ll leave you to discuss that in the comments.)

Still, it’s a small percentage who turn Amazon’s “nothing” into something—thousands upon thousands of authors go unnoticed—but it’s an opportunity all the same for those with grit and determination. Who does it hurt if most people fail, if they’re happy to have had the freedom to try? (And who determines what constitutes failure vs. success?)

Well, some might argue that allowing people to publish sub-standard material (also known as crap) is not helping anyone. Such an argument might be considered elitist (who’s to say what’s crap?) unless you’re able to demonstrate that these new opportunities are hurting writers in the long run—in a way that these writers would understand and agree with. There might be a way to do that, but that’s for another post.

Getting back to ways my proposal is flawed …

2. Authors have limited interest in spending additional time on marketing, promotion, and platform building.

Most authors would greatly prefer their publisher pay them more money (and they’ll use that money to pay a marketer if needed), rather than be given tools and community to support their livelihoods. While I personally might find this a short-sighted view—one that makes the author more dependent on the publisher than she ought to be—it’s hard to argue with. Authors typically have skills that make them wonderful at writing, but lousy businesspeople, and as much as I believe in finding ways to change authors’ whole mindset, approach, and idea of what it means to be entrepreneurial and empowered on the business side, there’s no arguing against the fact that nearly everyone does better when they can focus on their strengths and minimize the time they spend on everything else.

(I do have to put a big asterisk on this, however: I’m speaking primarily of creative writers and storytellers, not non-narrative nonfiction writers. Non-narrative and non-creative writers really need a whole other discussion, and likely pose the biggest flight risk from the Big Six. See: Tim Ferris, though he’s reportedly not too happy right now with his Amazon deal and lack of print sales.)

Thought of another way, if you believe the government should fund arts and artist grants—in part because the arts can’t and shouldn’t be run entirely like a business and deserves societal support because its value and strength gives even more back to society as a result—then you’re probably sympathetic to authors also being supported by publisher-patronage, and not burdening themselves with the business of their art. Workaday concerns are a distraction, and writing great things requires focus and huge amounts of uninterrupted time.

Also, when publishers support a project, they generally are able to provide more skills, strengths and resources than a single author can manage working alone. (That is certainly debatable, though, and depends greatly on the author.)

3. The Big Six will never have sufficient motivation to do more for authors than they already do.

Only an unfailing idealist like myself would think a Big Six publisher would expend resources on author relations and support. As long as the publisher can offer a reasonable deal, or lend the stamp of approval that authors crave, or provide quality editorial support, that is likely more than enough to prevent the author from moving to another arrangement if they’re not entrepreneurially minded to begin with.

Or: It boils down to three desirables that publishers offer.

Money

Service

Status

The publishers are getting increasingly challenged on the first (money), and they’re now having to prove they provide the second (service). My presentation too rests on the theory that authors may choose alternate paths that bring more money (and in some cases, more service) since so many are dissatisfied with Big Six service (including—but not limited to—editing, marketing/promotion, and publicity).

That leaves us with status. I’ve long extolled the virtues of tools and technology that empower the author, give them more insight into their readership—and power to grow and mobilize it—and democratize the publishing landscape. However, I can’t ignore human nature, which pushes us to seek validation and gives us status anxiety when we lack the traditional signifiers of approval. (Here enters the old self-publishing argument that readers decide what is “good” rather than traditional gatekeepers. This argument is very convenient and necessary for the author without traditional signifiers of approval.)

While plenty of authors successfully publish and gain a following without first gaining approval or permission, most are rightfully susceptible to the honor and prestige that comes with being anointed or accepted by a particular house, editor, agent, prize, review … choose whatever status symbol you like. Furthermore, even if your book utterly fails (on a commercial level) with a traditional publishing house, being able to claim you’re published by Penguin, Random House, or HarperCollins is a kind of currency in itself. That can open doors and lead to other types of paychecks.

The shrewdest authors—those who are primarily interested in their long-term business success and could not care less about acceptability on New York’s terms—will be the fastest to find other paths, and that’s exactly what’s happening. What are these other paths? Well, Amazon KDP, Smashwords, and numerous other DIY services are only part of the picture. Services such as Rogue Reader, Brightline, and various author collectives are emerging as competitive partners to shoulder the risk—and these are just the early days of such models. Given industry change, a start-up can reasonably challenge publishers on at least 2 if not all 3 of the desirables mentioned above.

Still, for my idealistic vision to be taken seriously, the Big Six (maybe soon to become the Big Five), would have to lose valuable authors. They’d have to suffer. So far, the loss has been minimal, and most self-publishing authors who strike it rich are only too happy to sign with a big player and see their sales skyrocket into the millions from the hundreds of thousands. A lot more has to change in the industry to convince publishers to be more service-oriented toward their authors. But if and when it does change, will it be too late to convince authors who offers the best partnership?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on my presentation—and this post, serving as an anti-presentation!—in the comments.

October 22, 2012

3 Steps for Using Prompts to Write Better & Get Published

In January of 2007—as a New Year’s resolution—I decided I was a writer. I resolved that I would stop saying that I’d start writing “someday” and instead would sit my backside in the chair and start writing now. No more excuses. I was a writer and I would start acting like one. That was when I started using writing prompts.

For the first several months after deciding to be a writer, all I wrote were writing exercises. Many were from books, like the ones listed in this post about prompt books that Jane wrote earlier this year. At first, I would work my way through prompt books one at a time, forcing myself to write something for each and every prompt, even if the result was awful. Before I knew it, I had produced several short stories (some of which eventually got published), I had put together a writing sample that helped me get accepted into an MFA program, and I even completed my first finished draft of a novel. All because of a few writing prompts.

Looking back, I realize there was a method to the madness, though I didn’t know I was doing it at the time. Through a simple three-step process, I built up my writing stamina and got tangible results just by doing writing exercises, and you can do it too. Here’s that process in a nutshell:

Build Stamina Through Practice

Develop Mastery of Techniques

Apply Prompts and Exercises to a Project

Step 1: Build Stamina Through Practice

For the first six months after I decided I was a writer, I wrote nothing but exercises. These prompts weren’t exactly fun. In fact, writing them was about as enjoyable as snuggling with a porcupine, but I would muscle through each one through sheer force of will. Then one day, instead of stopping when time was up, I just kept writing, and before I knew it I had the first two pages of what would later become the short story and writing sample that would get me into graduate school.

When you do prompts and exercises, you build a writing habit. It’s the writing equivalent of practicing your scales; you get used to doing the work, whether you like it or not. Then when it’s time to perform, to write “for real,” you’re ready.

There’s an old musician’s joke:

Q: What are the three steps for getting to Carnegie Hall?

A: Practice, practice, practice.

Prompts and exercises are a writer’s practice. When you practice writing, you also train your brain to write something—anything—even when your muse has decided to phone it in. Even if you love writing, there will come a day when you just don’t feel like doing it. That’s when practice comes in handy because it gets you through those moments. After all, anyone can write when it’s easy, when the story is exciting and and the characters fresh and fun. Real writers work even when the story hits a rut and the characters get on their nerves. Real writers write when it’s hard.

Step 2: Develop Mastery of Techniques

Once you’ve built up your stamina, the second step is to master the craft. One easy way to do this is to reuse the same writing prompt, but take a different approach each time. For instance, suppose you want to brush up on point of view:

Point of View Exercise: Choose one writing prompt, then roll a die. Do the prompt using the point of view specified by the number on the die.

1 = First Person

2 = Second Person

3 = Third Person Limited

4 = Multiple Points of View

5 = Objective

6 = Omniscient

Note: For a quick explanation of different points of view, check out this cheat sheet.

But you don’t just have to use prompts for studying point of view; you can also use them to practice any number of writing techniques, such as description, dialogue, exposition, flashbacks, even theme. Just choose a prompt and combine it with a technique you want to master. Then start writing.

Step 3: Apply Prompts and Exercises to a Project

One of the most common excuses I get from writers for why they don’t like writing prompts is: “I need all the writing time I have for my novel. Prompts are a distraction.” This is where step three comes in. Once you’ve built up your stamina and have an arsenal of writing techniques, you’re ready to start applying prompts to your current work-in-progress.

I know one writer who hates doing exercises, and yet she will be the first to admit that it was a writing prompt that helped her solve a significant plot problem in her current novel. It happened one day while my writer’s group was doing an exercise. In an effort to multitask, this writer decided to use one of the supporting characters from her work-in-progress as the focal character of the exercise. That way she was still somewhat working on her novel even by doing this unrelated exercise. What resulted was a scene that turned her novel on its head and helped that writer figure out a major plot twist that was giving her trouble.

Do’s and Dont’s

Do give yourself a moment or two to consider how you can apply this prompt to your current project before you dive into the exercise.

Don’t pigeonhole yourself. Your current project might focus on character A, but you can use the prompt to explore characters B, C or D instead.

Do explore other environments. If your story takes place in your protagonist’s hometown, try using a prompt to explore what your protagonist is like in a different setting. Send your protagonist on a road trip, honeymoon, or even to jail.

Don’t pick and choose your prompts. When I teach, I give students one—and only one—mulligan (golf term for do-over). If you choose a prompt that works with your project, then you defeat the purpose of doing the exercise altogether. It’s when you push your story beyond the expected and into new and scary directions that you make real breakthroughs.

Take-Home Message

Using these three steps, you can get a lot of mileage out of even just one collection of prompts. To help you get started, get your hands on one of these prompt books recommended by Jane, or check out these ten prompts featured in this post, also by Jane. You can also use the Writer Igniter, a web app just launched over at the DIY MFA site, to generate a virtually infinite number of story ideas. Then all you have to do is build your stamina, master your skills, and apply these prompts to your work-in-progress.

October 17, 2012

Is Your Author Website Doing Its Job? 6 Things to Check

Today’s guest post is by Laura Pepper Wu, the co-founder of 30 Day Books, a book studio that provides marketing tools and resources for authors wanting to find more readers.

Recently, I did some informal research about how authors view and use their websites, and the results were a little disheartening.

Many authors have a website simply because they have been told that they should have one as part of their online marketing strategy. The problem is, there is very little strategy involved at all; rather they build a site without really knowing why they’re doing it.

Without truly understanding why having a website is necessary—or what its full potential is—a site will collect virtual dust. In some cases having a bad website can be worse than having no website at all!

I like to think of an author’s website as the homebase of their online efforts. It’s the hub where, unlike with social media, you are fully in control of the content you can share and the image and brand you project. It’s a place that allows you full-on engagement with your readers without distraction.

In between book releases, you can keep the momentum going and communicate with your readers as frequently as you want. You can also attract new readers through your blogging, video blogging or newsletters hosted on your site.

Here’s a list of 6 things that a good author website could—and should—be doing for your career. It’s not an exhaustive list, so I’d love to hear your advice in the comments below!

1. Build your mailing list.

Many people avoid collecting e-mail addresses because they think that having readers and followers on their social media accounts is enough.

But you can speak to your readers much more directly through a newsletter: give them “sneak peeks,” cover reveals, let them know about promotions, share your news, etc. And the response rate is usually much higher than if you did this on your Facebook Page or on Twitter.

If you can collect the e-mail addresses of even a small percentage of the people who visit your site during the launch of your first book, then, when you’re ready to launch books two and three, you can let your readers know directly without depending on them seeing it on their fast-moving social media feeds. Since they’re already your fans, you’ll have a “ready to buy” audience, which helps your book launch gather momentum and be successful early on.

Action Tip: Not collecting e-mail addresses is one of the biggest regrets of authors who are publishing their second books, so learn from their mistakes and get proactive! Mailchimp is a great e-mail management system that is free up to 2,000 subscribers.

2. Host content that YOU own.

The writing and content you build on your website is YOURS and no one else’s! Communicating with readers on your Facebook page or other social media accounts is an important part of your online marketing, but social media platforms change all the time—and the content built there can get lost. It was recently reported that Facebook recently closed down the Cool Hunter’s page with 788,000 members on it and five years of content that was non-retrievable.

Action Tip: Your website is evergreen for as long as you want it to be. It gives you brownie points with Google, and it can’t be deleted. (It also doesn’t compete with baby pictures, vacation snaps or news of engagements, which soon distract even the most loyal reader-fan!) Split your marketing time between social media and creating content on your own site.

3. Provide media with info about you and your book.

You should have a dedicated media page with cover images, blurbs, author bio, purchase links, and so on—a “one-stop shop.” Bloggers, site owners and other media will love you for it! It avoids the need to e-mail big attachments back and forth and makes their lives easier—meaning they’re more likely to feature you.

Action Tip: Create a dedicated page on your site just for media folk. Check out this post for tips on how to build a great author media page.

4. Engage and interact with readers.

Engagement is becoming a clichéd word in the online marketing world; I prefer the “I feel like I know you” effect! There are people online whom we feel incredibly familiar with, even though we’ve never met them in person. Through video, e-mail newsletters and two-way conversation on your blog, you can create this same feeling about you in your readers. Jane is a wonderful example of how this can be done; Gretchen Rubin of the Happiness Project is another great example.

Action Tip: Respond to blog comments and social media mentions as much as possible to engage with readers. Think of it not as you in front of a classroom speaking to an audience, but as you standing side-by-side with friends and having a conversation.

5. Showcase yourself as a professional.

Your site should show that you take your career as a writer seriously. No matter what publishing route you are planning to take, if you want to do a book signing, an event at your local library, be featured in the local press, or land any noteworthy gig, a professional-looking site that’s easy to navigate makes a big impact on others. People judge a book by its cover—and by its author’s website!

Action Tip: Looking professional doesn’t mean spending a ton of money on website design. Using WordPress along with a nice theme will take care of design, then including specific content on your site—such as a media page, a well-written about page, high-quality images of your book cover, and quality author headshot—will also go a long way toward showing that you’re adept.

6. Persuade potential readers to take a chance on your book!

In one place, you can curate a sizzling book description; showcase reviews from your various platforms (Amazon, GoodReads, screenshots of Tweets); add social proof, such as awards you’ve won or bestseller status; and write a blog that your ideal readers will enjoy and respond to. What better way to convince a potential reader that they’re going to enjoy your work?

Action Tip: Be sure to include buy links in several visible places on your site, and make it as easy as possible for readers to purchase your books if they want to. Your website is, after all, the perfect place to find you more readers.

Now over to you! What is your website doing, or not doing, for your career as an author?

October 16, 2012

5 Literary Journals Born of the Digital Age

Today’s guest post is by lit addict, movie junkie, writer Emily Wenstrom.

A new generation of literary journals is taking advantage of technology to offer something fresh and creative to the literary journal scene. Here are five of my favorites, ranging from those with niche audiences to those with experimental approaches.

Brittle Star

For the newbie

Don’t be intimidated by this literary magazine’s international reach—it’s earned a reputation for lending its pages to first-time published writers. Featuring poetry and short fiction, you can pay for print versions, but all content is available for free online. Visit Brittle Star.

433

For the sound geek

While your coworkers listen to their favorite jams, you can get your daily dose of writing straight from your headphones. This publication offers short stories in podcasts—read by the authors themselves. 433 is looking for “edgy, engaging stories about modern life—stories that work well when read aloud.” It accepts stories as long as eight minutes, but look to the zine’s title for the ideal length. Visit 433.

20×20

For the artiste

More than just short stories, 20×20 reads like an arts scene mashup. It features lovely black and white photography, poetry, short stories, and The Blender, where visual and written arts meet. Each issue’s art stems from designated meta words. Published artists receive a complimentary print issue and others can purchase one, but all content is available online for free in a slick magazine format. Visit 20×20.

Beat to a Pulp

For the anti-artist

More of a blog than literary journal, Beat to a Pulp publishes one piece of short pulp fiction (4,000 words or less) each week. It focuses on hard-boiled pulp, but also accepts action/adventure, westerns, sci-fi/fantasy, and horror/thriller. The content is very accessible, and the design suits the theme—a retro-pulp look. Visit Beat to a Pulp.

Short Fast and Deadly

For the extremist

If you’re looking for a challenge or just a quick booster shot of creative writing, this is your place. Short Fast and Deadly embraces the shrinking attention span with the tagline “No attention span? No problem.” Dubbing itself an eLit mag, it’s a place where “brevity reigns and the loquacious are sent to contemplate their sins in the rejection bin.” And did I mention the work they publish is short? No really, we’re talking super short. The maximum character count—not words, characters—is 420 for stories, 140 for poetry. So I hope you like Twitter. Expect heaping amounts of free-form from each monthly issue. Visit Short Fast and Deadly.

None of these suit your style? Good news—these listings are the tip of the Internet iceberg. There’s something out there for every taste and preference, so if you’re looking for something in particular, start searching! A great place to start your hunt is a directory like Duotrope.

What literary journals do you love that embrace the online experience? Let us know in the comments.

October 15, 2012

Q&A on Copyright With an Attorney

By far, I receive the most questions from writers on copyright, mainly due to this post: When Do You Need to Secure Permissions? So I feel very lucky to have found an intellectual property lawyer, Brad Frazer, who is friendly and enthusiastic about providing answers to writers on a range of copyright issues. He’s written two posts for this blog (Copyright Is Not a Verb and Trademark Is Not a Verb), and today, I’m featuring a range of Q&A sparked by responses and questions to those posts. I hope you find this information helpful, and I’ll be featuring more from Brad in the future.

As a thank-you to him, I recommend checking out his novel with Diversion Books, The Cure. Visit Amazon and sample his first chapter for free on your Kindle.

Isn’t registering your copyright something the publisher does? And if not, and you haven’t done it within three months of publication, then what?

Yes, many times your publisher will handle the copyright registration. But there is no industry-wide rule that says an author may not or should not register her copyright in her works. Said another way, a publisher will not look askance at you or reject your work simply because you have already registered your copyright. It is a big risk to decide not to register your copyright thinking you will wait for your publisher to do it. This is so because (1) in the U.S., you must register your copyright in order to have a remedy to sue an infringer in federal court; and (2) you should register your copyright within three months of the date you first giveaway a copy of the work or sell a copy (“publication”), so as to have the full panoply of remedies available to you should you have to file a lawsuit. If you do not register within that three-month window, and if you do sue for copyright infringement, you will not be able to recover your attorney’s fees or what are called “statutory damages”—even if you win. So there is a huge financial incentive to register within that three-month window.

Side note: “Publication” is defined in copyright law to mean “the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending. The offering to distribute copies or phonorecords to a group of persons for purposes of further distribution, public performance, or public display, constitutes publication. A public performance or display of a work does not of itself constitute publication.” Like other legal issues, it is a matter of reading and applying that statutory definition to your situation. I always advise clients to err on the side of caution and register their copyrights as soon as the work is completed and not wait for a “publication” event.

Remember: Registering your copyright is NOT THE SAME as merely putting a “circle C” symbol on the work. In fact, you generally would NOT want to put a “circle C” on an industry-related submission to an agent or publisher. Just because you have registered the copyright does not mean you must put a “Circle C” on the work.

A former editor of my novel (still in the works) is trying to claim my work as her own, posting it on Twitter and other social media sites. It has not been registered with the Copyright Office and is not even complete yet. Do I have any recourse to make this stop?

Yes, you should register your copyright in the work as it exists now. Registration will give you a remedy in case you wish to file a copyright infringement lawsuit. Normally, after you register the copyright you or your lawyer would send the infringer a cease and desist letter and then, if there was no response, file a lawsuit to make it stop. Or, since this is apparently online infringement, you could send a Digital Millennium Copyright Act Take-Down Notice to the sites posting the infringing content.

If I write a short story then blog it and it ends up in someone else’s book, do I have any recourse?

Yes, if you have registered your copyright in the short story with the U.S. Copyright Office, you would be able to file a lawsuit for copyright infringement against the person who used it in their book. You do need to register the copyright to be able to file and maintain that lawsuit. Without registration of the copyright, your legal remedies in the U.S. are somewhat limited.

I’m a self-published author who, like most self-pubbers, has begun with one electronic format. As time goes on I will publish my novels under other formats, and then, who knows? Paperback, hardback, audiobook … I see from the U.S. Copyright Office site that I can file an electronic copy of my work; does that filing now cover all possible formats of the same work? Say in five years’ time I have an audiobook out of Novel #1 and someone pirates it, and by this time I can afford a lawyer to go after the pirate. Does my original filing of, say, a PDF of the text of Novel #1 cover this case?

Assume that you write a book using Microsoft Word. As you know, you own a copyright in the book upon the act of typing the words into the Microsoft Word .docx file. That is a sufficient act of reducing your idea to a tangible medium to create a copyright. If you print the book out on paper, you still own a copyright in the book. If you convert the .docx Word file to .epub or .mobi or .html, you still own a copyright in the book.

Because you self-published, I assume your book exists today both as a Word .docx file and a Kindle .mobi file? You own the copyright in the book—file type does not matter. If you turn it into a PDF, you still own the copyright. As long as the words are there, the medium does not alter the basic idea that you, as the author, own the copyright in the work.

When you register that copyright that you own in that book, you will be required to upload an electronic copy of the book called the “Deposit Copy.” The Copyright Office upload protocols require that the Deposit Copy be in specified formats—I do not think they accept .mobi or .docx. So, you will convert the book into a PDF file (or whatever) to upload it, and voila!, you will have filed a copyright registration application.

Once that is done and you receive the Registration Certificate in the mail in a few weeks, the words that comprise the book are protected by a registered copyright, and will be, even if the book is published in paperback, hardback, EPUB, or some other digital format. As long as the words are all there in the subsequent version of the book, that original registration will cover it, even if the file format of the book changes.

The EXCEPTION to all this is an audio book, the example you picked. When you create an audio book—a sound recording of someone reading the book—you will need to file a new copyright registration application to register an additional copyright in the sound recording. You will upload or mail in a copy of the sound recording, and that will become the Deposit Copy to support that application. You will then own a registered copyright in the sound recording AND the print version.

Note that when you write the screenplay based on the book, that will be what is called a derivative work, and you will need to file another copyright registration application.

But except for sound recordings and derivative works like a screenplay (in which the words are changed), one registration of your copyright in the book as a PDF (or whatever the required Deposit Copy file format is) will cover multiple print formats of that same book.

I will do the online registration with the Copyright Office at the Library of Congress within three months of publishing my YA novel. It is affordable, I am pleased to see. However, I live in Australia. Is this still acceptable? Or is this only for U.S. citizens?

Each country has its own copyright laws and registration schemes. In some countries, registration is not needed to fully protect your rights, for example. Registering your novel with the United States Copyright Office within three months of the date of first publication will give you remedies for copyright infringement that occur within the United States. A U.S. registration can also help you with an act of infringement that occurs in another country, like Australia, if it is a member of the Berne Convention, an international copyright treaty. (Australia is a Berne Convention country.)

There is no downside to your registering your work in the U.S. if there is a chance your work will be copied without your permission in the U.S. or in a Berne Convention country. You’ll need to consult an Australian copyright lawyer to see if an Australian registration is needed/required.

What if a worship pastor (whose job description includes writing worship songs), writes a worship song on his own time and without church resources, BUT that song is performed at the church where he works at? I know that if it is written in his office, on church time, with church resources, the church “owns” it. I know that, typically, what is done on one’s on time without church resources is not owned by the church. HOWEVER, it gets fuzzy for me when it’s a part of his/her job AND it’s “promoted” (performed) at the church.

Your question arises under what is called the “work for hire doctrine.” Generally stated, it means that the copyright in a work created by an employee during the course and scope of their employment is owned by the employer. Period. Where it gets hazy, as you state, is when it is not clear if the work was authored during the course and scope of the employee’s employment.

Here, the fact of the song’s being performed at the church doesn’t really matter, in my opinion. This is going to boil down to these two issues: (1) was the worship pastor an actual employee (as defined by the IRS) of the church; and (2) was the song authored during the course and scope of that employment? There is a great deal of case law on that very issue (see, e.g., the Reid case), since many times it is not clear what is within the “course and scope” of the employment—as in your case. Here, it seems to be helpful that the pastor’s job description includes writing worship songs—that is a fact that would tend to show that the song at issue was written as a work for hire, and thus the church owns the copyright, assuming the employment test is met. But without a full-blown analysis of all the facts and the case law in your jurisdiction, I cannot really opine further.

Once again, my thanks to Brad for being so generous with his time and advice. Check out his thriller, The Cure, over at Amazon.

October 12, 2012

Plympton: A New Effort to Produce Successful Serial Fiction

In the past year, I’ve run two posts specifically related to serial fiction—a guest post by Roz Morris and a Q&A with Sean Platt. I also wrote a more in-depth piece for Publishing Perspectives on the topic last year.

Last month, Amazon announced Kindle Serials: a new, formal publishing program, exclusive to Kindle, that focuses on publishing serial fiction. Customers who pay $1.99 automatically receive all installments in a series. (For a insider analysis of this program, check Porter Anderson’s write up.)

Plympton—a new digital publishing start up—is one of the companies that has partnered with the Kindle Serials program. Yael Goldstein Love, Plympton’s co-founder and editorial director, was gracious enough to answer a few questions about what’s happening.

E-book serials have been around for a while, though I know some authors have struggled to make it work without a subscription infrastructure in place to help facilitate. Now with Amazon launching Kindle Serials, and formalizing the approach, do you think this changes the game?

I do. There’s been some great stuff happening in serialization for e-books over the past several years and it’s an exciting space. But it’s still a niche market—a passionate and thriving one, but niche all the same.

What we at Plympton want to do is to make serials a standard format, a third option beside novels and short stories. We want serial to be a format that every fiction reader loves to read and every fiction writer at least considers experimenting with at some point.

It sounds bold, I know, but I don’t think it’s far fetched. Think about what’s happened with television. As a culture, we’ve become addicted to serials like Mad Men and Breaking Bad, and they’ve arguably become the dominant form of cinematic storytelling, replacing the movie for sheer exuberance and originality.

Because of shows like these we’ve actually come to expect our big stories to arrive in bite-size chunks. And I think that’s a happy turn of events because bite-size chunks is a compelling way to experience a story. There’s the delight of the cliffhanger, but there’s also the arguably even deeper delight of the time between episodes, anticipating and speculating about what will happen next. That break between episodes makes our relationship with the characters feel more intimate because they can surprise, disappoint, and betray us in real time.

All of this is to say that I can see serial fiction becoming entirely mainstream, and it’s our goal at Plympton to make that happen. Amazon’s investment in Kindle Serials certainly makes our job easier because what’s needed most at this stage is reader education and no one is in a position to reach readers quite like Amazon.

Some have argued that the “truest” serial fiction writers are not after profit. Or, put another way, “pure” forms of serial fiction in contemporary terms—in Asia with cell phone novels, or in fan fiction—are put forth in a very spontaneous way that’s linked to a community rather than revenue. Seen in this light, a formalized, Amazon-corporate approach to serial fiction would seem to kill the essence of it. What do you think? (Just playing devil’s advocate here.)

I guess what I’d say to that is that serials have a long history. In the latter half of the 19th century a novel was rarely published as a book before first being serialized in a newspaper or magazine. We’re not just talking Dickens here. We’re talking Mark Twain, Henry James, George Eliot, Herman Melville, and that’s just in the English language. Flaubert, Tolstoy, and Dostoevksy published their most famous novels as serials as well. And these writers didn’t publish serials just for the love of the written word. They did it to make money. Most of the great (as well as not so great) 19th century novelists needed that money in order to survive, and in fact that was part of the appeal of the serial format: it gave writers an additional income stream, before their full books went into print.

We at Plympton see income for writers as one of the draws as well. We want writers to get paid for their writing. They should. Writing is hard, passionate, soul-consuming work. A person should be remunerated for it. In an ideal world a person who does it well enough should be able to make a living from it so that they can devote themselves to it entirely. That’s our dream, anyway.

Kindle Serials (through which Plympton titles are available) cost $1.99. I know from my conversations with another serial writer, Sean Platt, that it can be very difficult to make serials pay off at that kind of price point. I’ve heard speculation that $1.99 is an introductory price from Amazon, and the price may increase, or there will be other revenue lines from the project (e.g., print compilations). Any thoughts on this?

It’s not what we would have done ourselves, but if Amazon knows anything it’s how to make money so we’re trusting them on this. I can’t say anything more about their plans, but I will say that we have a lot experiments we’re eager to run in this area and we’ll be doing that with our next titles.

When I researched serials last year, it became clear that readers of serials come in many different forms. Some people will read installments as they are released, others will wait for the entire book to be available, and still others look for an edited print compilation. Is Plympton targeting all of these reader types, or just a segment?

Yeah, we’re targeting all these reader types. Our three titles in the Kindle Serials program will be released as paperback books when the serialization is complete. We’ve also talked amongst ourselves about doing an edited print compilation for some of our future titles. We’re very open to experimentation here. We have a lot of schemes up our sleeves, some of which will no doubt be tremendous flops, but some of which—who knows? Maybe we’ll find that sweet spot that gives a book nine lives. Most books’ lives are far too short, don’t you think?

Finally, many authors I spoke with [for the Publishing Perspectives piece] agreed that the process of serialization worked best almost as a marketing device—to build buzz and spread the word before a final book/compilation was released. This means the serialization becomes, in part, a gimmick to sell the final product, but I don’t think Plympton has been launched with this as the philosophy?

No, that’s not our philosophy at all. We really believe in the serial experience. We believe it can enhance reading in all sorts of ways. There’s that anticipation and speculation I mentioned above. There’s also the fact that serials are well-sized to fit into a busy person’s life. And I can’t help thinking that serials distill the essence of what we love about fiction in the first place—the way it mimics life but more beautifully, more instructively. The way it gives us a chance to actually be someone else for a while, inhabiting an unfamiliar psyche. When we live inside these stories for months, years even, it takes those features of fiction to a whole new level.

And here’s where I start to sound like a zealot: I actually think this way of reading can enhance our empathy and our open-mindedness by forcing us to stay inside other minds for longer periods. I have a theory that if Uncle Tom’s Cabin hadn’t been serialized—which it was, by the way—but just published as one complete book, it wouldn’t have had the effect that it had on thousands of white readers. It would have been easier to read it, put it aside, and forget the uncomfortable fact that something horrific was happening in this country. But instead readers had to sit with it for months, worrying about the characters between installments, thinking and wondering as they went about their lives. I bet that made it a lot harder to forget those uncomfortable facts. Not that I’m saying we should all start reading serials because if we do we’ll change the world. (Although how’s that for a slogan?) I mention it mainly because I think it highlights just how much depth and richness the serial experience can add. It’s the furthest thing from a gimmick; it’s an art form.

What do you think about serial fiction as an art form? Do you read serials—or will you give them a try? Give us your thoughts in the comments.

October 8, 2012

Steal Your Way to Better Writing

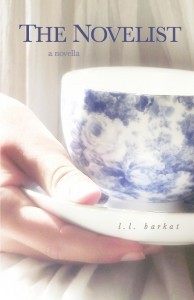

Today’s guest post is by poet and editor L.L. Barkat. You may remember her from an earlier guest post, You Don’t Need a Degree to Find Your Voice.

“I can’t write poetry,” she said. And it was true.

This girl—who read Macbeth at age twelve and argued with the commentaries, who in the same season read all of Tolkien in less than a week and memorized a good deal of the embedded poems—could not write poetry. Everything she tried seemed shapeless and wan. This defied logic. At least mine.

I’d been an English teacher and a writer myself, and the formula I knew was fairly simple: excellent readers are usually excellent writers. This is why every editor will tell you that you must be a reader if you hope to become a better writer. No question. There’s a strong connection.

So I was puzzled, to say the least, when my own daughter could not pen a poem with any life in it. Not that anyone would care, since few people recognize that poetry is important and formative for other kinds of writing (including business writing). But I cared. And my daughter, watching her talented younger sister, cared.

Maybe this is one reason she stole my Norton Anthology of Poetry when it arrived in that trim Amazon box. Maybe that’s why she attempted what I’d never seen another pre-teen attempt with such vigor (or at all): sonnets, sestinas, pantoums, villanelles. And she was shockingly good for her age, sometimes writing a sonnet in ten minutes flat (and that with her mother bothering her to please take a phone call from Grandma).

Here’s the point I want you to take away: writers are opened by different approaches, sometimes radically different. To this day, my daughter pleads with me to read the how-to writing books. She challenges me to write poetry in form. I humor her a bit, but the truth is that these approaches do not help my writing the way they’ve helped hers. I need approaches that feel altogether more organic—Annie Dillard over On Writing Well.

And that is why I had to write The Novelist. As a writer with four books already to my name, I had no organic approach to my new genre of choice: fiction. The how-to books only paralyzed me; I’d been stalling on fiction for just about forever, with no hope in sight.

Where was the book I needed to teach me, and others like me, the secrets of this tantalizing genre? Where was the equivalent of my daughter’s Norton Anthology? As it turns out, it was inside me. I just needed to steal a series of 4 a.m. writing slots, to find that I could learn to write fiction from story itself. Never mind that I would have to be the one to actually write the story.

What kind of writer are you? Maybe you’ve been waiting to find the approach that will open you. Maybe if the how-to books have not taken you where you want to go, it’s time you learned to write through story itself.

Sure, I can recommend The Novelist. And remind you that anything that opens your inner writer is a real steal.

Additional suggested reading

My book Rumors of Water

The Anthologist by Nicholson Baker

The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

Or, read a chapter of The Novelist

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers