Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 128

August 1, 2016

5 Ways to Keep Writing When Life Intervenes

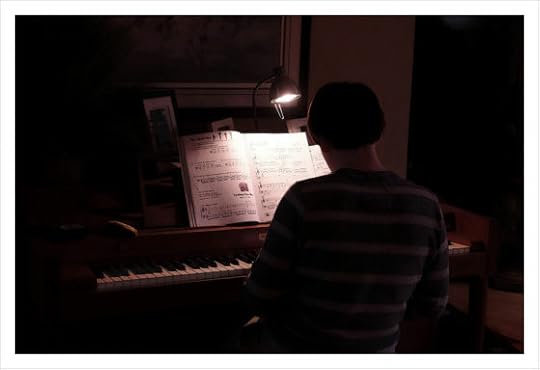

by Cathy Baird | via Flickr

Today’s guest post is from author and editorial director of Writer’s Digest Jessica Strawser (@jessicastrawser); her debut novel, Almost Missed You, releases in spring 2017.

“I had every intention of [finishing this manuscript / meeting this deadline / honoring this promise to my critique partner / fill in the writing-related blank] but then [I was diagnosed / my father needed special care / my kid broke his leg / we had to relocate / my marriage fell apart / fill in the life-related blank].”

This post isn’t about writing through the little things (teething babies, cold and flu season, overtime at your day job)—though we all know the little things can be tough to write through. This is about writing through the big stuff.

I’m a longtime member of the writing community on Twitter and in the blogosphere but a (very) latecomer to Facebook, as a fairly private person with a fairly public job who has grappled with how to separate the two. Earlier this year, when I finally made the decision to set up my personal profile alongside my author page, I was looking forward to participating more actively in the groups of which I am a member—places like the Women’s Fiction Writers Association, which had moved its forums almost entirely to Facebook.

And those connections have been wonderful. But what I’ve also seen amplified across a range of writing groups on that platform is something I’ve been glimpsing elsewhere for years—so many writers, too many writers, who are struggling to write through their own variations on the “qualifying life events” mentioned above. I read their posts—anguish, apologies, frustration—and my heart aches for them.

Sometimes, when something big gets in the way of your writing, you want or need to just step away. Fair enough. When my family and especially, always, my kids really need me, there’s no contest. And that’s as it should be. We’re all human—editors and agents included. People will understand.

But sometimes, you don’t have much choice but to find a way to keep writing while you’re dealing with everything else. Or you want to go on, feel a need to go on, but can’t see how, and that only makes you feel worse.

This, I know something about.

In November 2008, I was hired as chief editor of Writer’s Digest magazine. I’d started my career there years earlier, then moved on to other things—but everyone who knew me knew that the opportunity to come back and take the helm was essentially a dream job for me. I lined up my first cover story—I’d be interviewing (wait for it) Stephen King, alongside his friend and very different kind of bestseller Jerry Jenkins. My husband and family were excited, of course, but my best friend was hilariously so. She took me out to celebrate and would call with random updates about how she’d been telling everyone that I was interviewing THE King.

And then, in December, she was murdered.

The day of her funeral, a colleague dropped off the final page proofs of my first issue in a binder on my front porch. We had a printer deadline in a few days.

Editing a magazine might not tap exactly the same creative well as, say, writing a novel, but it’s not as far off as you might think. Our staff being relatively small, my job was relatively big—and I was still learning how to do it. I had to generate ideas, execute a vision, maintain a voice, strive for quality, work with contributors, interact with readers, write features, introduce each issue in a letter, blog.… You get the idea.

In the months that followed, let’s just say there were some distractions, piling like bricks onto my grief. Her cause of death was released in our local news and delivered to my inbox via Google Alerts while I was sitting in my cubicle, surrounded by office chitchat. I attended her killer’s arraignment one morning and was in by noon. I arrived home at the end of a long day to a subpoena in my mailbox.

I had my dream job—one I really, really wanted to excel at—and I was terrified that I wasn’t going to be able to hold it together.

It wasn’t easy, but I did. And so can you—whether you’re the one struggling, or trying to help a fellow writer in a tough spot. Here’s what I learned about how.

1. Give yourself permission to duck out.

Jane Friedman (the very same) was my boss at the time, and she took me into her office my first day back after the tragedy for a gracious moment of kindness: “If something ever comes up that you need to leave, just do it,” she said. “You don’t have to wait for my okay. Just explain later.”

I took her up on it only once or twice. When someone extends such kindness and trust to you, the last thing you want to do is abuse it. But just knowing that I could leave if I needed to made a huge difference. It took away a sort of panicky feeling I’d been fighting.

As a writer, you’re ultimately your own boss. So extend this same small kindness to yourself: If you ever need to stop, just stop. No questions asked. You may find that the pressure it alleviates is a great release.

2. Use your anger.

Go ahead and get the “I can’t believe this is happening at all, let alone when I have to _____ / am right in the middle of ____ / just committed to …” out of your system. Acknowledge it for as long as you need to—a week or two of hard commiserating, perhaps—but then do your best to set it aside.

At the root of that frustration and disbelief is likely anger, perhaps a sense of injustice. Why me (or him or her)? Why now? Use it.

For me, I channeled my fury at the person who had taken my friend from me. Was I going to let his actions take my dream job, too?

Not if I could help it.

3. Distract yourself.

I threw myself into my work. The distraction, I found, could actually be quite welcome, if I was patient enough to wait for my ability to concentrate to steady itself. I could spend my Saturday morning thinking about how I could no longer call my friend to see what she was doing later … or, I could go into my quiet office building, alone, and try very hard to think about something else. Something productive. Something rewarding. And fortunately, that time more than made up for any weekday hours where my focus just wasn’t where it should have been.

Probably somewhere in the midst of this life-altering chaos you stopped thinking of writing as something you wanted to do and started thinking of it as something you had to do. Some extent of this may be unavoidable, but the quicker you can turn it around, the better off you’ll be.

If you can start thinking of distractions as welcome rather than required, you’ll be on your way to reclaiming what’s rightfully yours: your joy, your creativity, your goal.

4. Let people know.

You might not want to talk about it, and that’s okay. But the more people who you clue in even a little bit to what’s going on, the more support you’ll get. Grief, tragedy, and illness can be isolating. Sometimes to get what you need—whether that’s friendship, a babysitter, a lunch buddy, a ride, a cup of milk for the mac ’n’ cheese you already boiled, or a butt in a chair at the book signing you didn’t have a chance to promote—all you have to do is ask. No one can help you if they don’t know what’s happening, what you need, or specifically how to help.

I had a neighbor land in the hospital with a nasty infection last year. Once she was home recovering with her two young kids underfoot, I sent her a “Let me know how I can help” text, expecting a standard “Thanks, I will” response, which is often how those exchanges end. Instead, she wrote back, “Actually, we’re pretty set on meals right now but might need dinner Tuesday, if you’re sure it’s not any trouble.…”

Guess what she got from me on Tuesday? It wasn’t any trouble. In fact, it was a relief to be able to help in a way that I knew was truly needed.

Be direct:

“It might sound crazy, but what would really help me would just be to have a quiet hour with my laptop between Dad’s appointments. He doesn’t like to be left alone at the hospital. Can you keep him company during lunch for me? I’ll pay.”

To circle back to my observation at the start of this post, whether or how much you want to share on your blog or social media is up to you, and may to some degree depend on who your networks consist of, what exactly you’re going through, and what kind of support you would find most helpful. I’ve seen support rallied in moving ways (from GoFundMe pages to prayer requests to dinner delivery signups), and I’ve also seen comment threads take random ugly turns for no good reason.

There can be an inherent pressure to share on networks like Facebook, and I’m here to tell you that you don’t have to post anything you don’t want to. (As I’m only now writing about some aspects of my own experience for the first time, eight years later, you can guess where I stand.) But opening up to a few carefully selected someones, if perhaps not everyone, can make a big difference.

5. Control what you can.

We most often hear this advice in the form of not dwelling on things you can’t control. But I’m here to tell you to stand your ground. Don’t let the bad stuff tinge any more good stuff than it has to. In trying to focus on what you can control, try to consider that your writing is one of those things, even though it might not feel like it right now.

It’s not going to be easy—but then again, when is writing ever easy?

I had writing dreams beyond the pages of WD, and once I had a few years of distance from my experience, I was setting out for them with a determination I’d not had before. Eventually, what I went through inspired a novel—one that did not ultimately sell but did land me an agent, sending me down a road of revisions and submissions that I’d learn a lot from. A moment of healing became, to my amazement, a New York Times byline, in the “Modern Love” column. And my next (entirely unrelated) novel did find a home—in a preempt.

I had writing dreams beyond the pages of WD, and once I had a few years of distance from my experience, I was setting out for them with a determination I’d not had before. Eventually, what I went through inspired a novel—one that did not ultimately sell but did land me an agent, sending me down a road of revisions and submissions that I’d learn a lot from. A moment of healing became, to my amazement, a New York Times byline, in the “Modern Love” column. And my next (entirely unrelated) novel did find a home—in a preempt.

Life can intervene without taking over. Take those famous John Lennon lyrics further, and try not to stop making other plans.

We writers are a tough bunch. And the rest of us are right here with you.

Connect with Jessica on Twitter (@jessicastrawser) and Facebook, and be sure to take a look at her debut novel releasing next year, Almost Missed You.

July 25, 2016

A Definition of Author Platform

by William Pearce / via Flickr

Author platform is one of the most difficult concepts to explain, partly because everyone defines it a little differently. But by far the easiest explanation is: an ability to sell books because of who you are or who you can reach.

Platform is a concept that first arose in connection with nonfiction authors. Sometime during the 1990s, agents and publishers began rejecting nonfiction book proposals and nonfiction manuscripts when the author lacked a “platform.” At the time—before the advent of the Internet or social media—that meant the nonfiction author needed to be in the public eye in some way (usually through mainstream media appearances) with the ability to spread the word easily to sell books. In other words, agents weren’t interested in the average Joe sitting at home who wanted to sell a nonfiction book but who had no particular professional network or public presence. Then, as now, they seek writers with credentials and authority, who are visible to their target audience as an expert, thought leader, or professional.

Visibility means: Where do your or your work regularly appear? How many people see it? How does it spread? Where does it spread? What communities are you a part of? Who do you influence? It’s typically not enough to say you have visibility. You have to show how and where you make an impact and give proof of engagement. This could be quantitative evidence (e.g., size of your e-mail newsletter list, website traffic, blog comments) or qualitative evidence (high-profile reviews, testimonials from A-listers in your genre).

Target audience means: You should be visible to the most receptive or appropriate audience for the work you’re trying to sell. For instance: If you have visibility, authority, and proven reach to orthodontists, that probably won’t be helpful if you’re marketing vampire fiction (unless perhaps you’re writing about a vampire orthodonist who repairs crooked vampire fangs?).

Do you need a platform to get published?

It depends. If you’re a fiction writer, no. Fiction writers should focus on crafting the best work possible. That’s not to say a platform is unwelcome if you have one, but an agent or publisher will make a decision first based on the quality of your manuscript and its suitability for the current marketplace. (That said, if you’re a huge celebrity or Internet star, it’s possible you’ll get a book deal based on that alone, and be paired up with a ghostwriter or publishing team to help you produce a bestselling book to take advantage of your stardom.)

It rips me apart to hear very new writers who express anxiety about their platform, especially when they have not a single book or credit to their name. Well, it’s not a mystery why platform is so confusing when you may not yet know who you are as a writer. First and foremost, platform grows out of your body of work—or from producing great work. Remember that. It’s very difficult, next to impossible, to build a platform for work that does not yet exist (unless, again, you’re some kind of celebrity).

However, if you’re a nonfiction writer seeking a book deal with one of the Big Five New York publishers, then you’ll need to develop or demonstrate that you have a platform. I discuss that more in my post on book proposals.

For memoirists and other writers working on narrative nonfiction, you can sometimes find yourself off the hook when it comes to platform. With narratives, the focus tends to be more on the art and craft of the storytelling—or the quality of the writing—more so than your platform. So a lot can depend on your credibility as a good writer; an existing track record of newspaper or magazine publication can often be sufficient to get yourself a book deal. However, one look at the current bestseller list will often betray publishing’s continuing interest in a platform: you’ll find books by celebrities, pundits, and well-established writers occupying a fair share of it. To help overcome the platform hurdle, it helps to be writing a narrative that is timely and taps into current hot topics.

Nonfiction authors shouldn’t despair if they feel like their platform is nonexistent. You may simply need to reconsider what type of publisher is a good fit for your book. Small presses, and especially university presses, have more interest in the quality of your work than your platform. And it’s not uncommon for successful authors to begin their careers with quieter publishers, then later sign with a New York house once they’ve built visibility and a strong track record.

What platform is NOT

A lot of people confuse platform building with marketing, promotion, and publicity. While those types of activities can build your platform, let’s be clear: being an extrovert on social media will not, by itself, lead you to a platform that interests publishers.

Platform is not about bringing attention to yourself, or by screaming to everyone you can find online or offline, “Look at me! Look at me!” Platform isn’t about who yells the loudest or who markets the best. It’s more complex and organic than that.

What activities build author platform?

Platform building requires consistent, ongoing effort over the course of a career. It also means making incremental improvements in extending your network. It’s about making waves that attract other people to you—not about begging others to pay attention.

The following list is not exhaustive, but helps give you an idea of how platform can grow.

Publishing or distributing quality work in outlets you want to be identified with and that your target audience reads.

Producing a body of work on your own platform—e.g., blog, e-mail newsletter, social network, podcast, video, digital downloads, etc—that gathers quality followers or a community of people who are interested in what you have to say. This is usually a longterm process.

Speaking at and/or attending events where you meet new people and extend your network of contacts.

Finding meaningful ways to engage with and develop your target audience, whether through content, events, online marketing/promotion, etc.

Partnering with peers or influencers to tackle a new project and/or extend your visibility.

You can’t build a platform overnight—unless you somehow become famous overnight. (If you do, take advantage of it, of course.) Platform is not something you can buy—buying followers or email addresses isn’t a platform because that’s not a meaningful audience who cares about you or your work. Being able to repeatedly reach and speak to people who know you and trust you is meaningful.

Some people have an easier time building platform than others. If you hold a highly recognized position (powerful network and influence), if you know key influencers (friends in high places), if you are associated with powerful communities, if you have prestigious degrees or posts, or if you otherwise have public-facing work—yes, you play the field at an advantage. This is why it’s so easy for celebrities to get book deals. They have “built-in” platform.

Platform building is not one size fits all

Platform building is an organic process and will be different for every single author. There is no checklist I can give you to develop a platform, because it depends on:

your unique story/message

your unique strengths and qualities

your target readership

Your platform should be as much of a creative exercise and project as the work you produce. While platform gives you power to market effectively, it’s not something you develop by posting to social media a few times a week. You’ll need to use your creativity and imagination, and take meaningful steps. It’ll be a long journey.

I like trying to persuade authors of the value of platform—at least when built organically—because it represents a meaningful investment in your lifelong career as an author. You shouldn’t rely on a publisher, agent, or consultant to find and “keep” your audience for you. If you find and nurture it on channels that you own, and on your own terms, that’s like putting money in the bank.

How to Grow Your Email List

by Hernán Freschi | via Flickr

This guest post is from Kirsten Oliphant (@kikimojo). This is the fourth post in a series about email. You can also read about why you should start an email list, how to customize your forms, and what you should put in your email newsletter.

Perhaps the element of email lists that excites (and frustrates) people the most is list growth. We all love numbers, don’t we? At least, we love numbers when they are on our side.

I hear people all the time waxing on about their 20,000 or 50,000 subscribers. Rarely do people talk about their lists when they have tens or hundreds or in the low thousands. You never see “Join my list of 48 awesome subscribers (one of whom is my mom)” on an email signup form.

The 10,000-subscriber mark seems to be the magic number. This is where agents and publishers take notice of nonfiction authors (listen to my interview with Chad R. Allen of Baker Books for more). Indie author Nick Stephenson heralds this number in his Your First 10,000 Readers course, and Bryan Harris of VideoFruit also has a Get 10,000 Subscribers course that is not geared specifically toward authors.

If you are one of the many people just starting with list growth or feeling frustrated with your far from 10,000 subscribers, let me give you some encouragement before I dive into practical tips for list growth.

Imagine you are asked to speak at a local event. Fifty or 100 or 650 people pack into chairs to hear you. Would you feel pleased and honored to look out over those faces?

If so, imagine your subscribers as your willing audience the next time you send an email. Don’t knock the small numbers. You can be pleased and encouraged with your current readership even as you strive to grow, whether your longterm goal is 1,000 or 10,000.

List growth is a battle, fought on the hill of very crowded inboxes. To be successful, you need to prepare by getting your foundation in order. Know why you are growing a list and which email service provider to use, customize your signup forms to engage readers from the start, and create a content plan.

It’s also a good idea to consider your ideal readers. A list of 10,000 random people will not be as effective as a list of 1,000 loyal fans. If you haven’t thought about who your target audience is, try this free guide to create an ideal reader profile.

Once you have a foundation in place and know who you are trying to reach, you will primarily grow your list on two main fronts: the home front of your website and the outside arena of social media and other platforms.

Optimize Your Website for Subscribers

Create Great Content

This is pretty simple: if you create great content, people are more likely to want to hear from you in their inbox. Great content isn’t enough, but if you aren’t giving value in your blog posts, people certainly won’t want to hear from you via email. Be sure every post is a quality post that relates to your ideal readers.

Make It Easy to Sign Up

Sidebar blindness (where we are so used to sidebars on websites we hardly see them) is a real thing. You can have a signup form in the sidebar, but you should also use other tools too. Consider using:

A smart pop-up that appears after a certain number of seconds (MailMunch is a good option)

A smart bar that hovers at the top of the site or the bottom even as readers scroll (try Hello Bar)

A feature box just below the header of the blog with a signup form (Plugmatter has a paid plugin for this)

Embedded forms within a post

Text links within a post

Forms at the bottom of every post

Forms in the sidebar

Clickable images that trigger a pop-up or redirect to a signup form

Clearly you don’t want to use all of these options all the time. Find a balance and make them noticeable but not obnoxious. Change them out a few times a year, but make sure there are a few signup options on each page and post.

Offer a Targeted Freebie

Another great motivator to grow your list is to offer a freebie of some kind. People often get stuck here on the freebie and I understand why: it’s hard to think of something that people want enough to give you an email address. This could look like a short ebook, a resource guide, a companion to a novel, or even entrance into a private Facebook community. Consider what you might want to receive from your favorite author or what content of yours people engage with the most.

Offer Content Upgrades

This is a fancy term for smaller-scale freebies that you offer in a single post, related to that post’s content. Amy Porterfield is the queen of content upgrades, with a free download for every weekly podcast episode. They are typically quick wins: a cheat sheet or a handy guide or actionable list. You can create a freebie and then embed a special signup form in that post that will deliver the freebie in the welcome email.

Optimize Your Social Platforms

Schedule Weekly Opt-ins

Sometimes I think we overlook the simplest method of list growth: asking people to sign up. To make this effective, don’t simply tweet that people should join your list. Consider different ways you can entice people, and then schedule out weekly (or with busy platforms like Twitter, daily) posts. Here are a few ideas:

Post a teaser before your email goes out, letting people know what they are missing if they don’t subscribe

Promote your freebie

Promote your blog post with the content upgrade

Creatively ask people to join (go back to the post on customizing your forms to think about language you could use)

Be aware of each platform’s ecosystem. You could post varying links to Twitter once or even twice a day because that platform moves so quickly. But on your Facebook page, even once daily might seem spammy unless you are posting many times a day.

Place Links in Your Profile or Bio

Many people simply link to their website in the profile or bio for each platform. Instead, consider linking to a landing page on your site for your email list. If you do this, make sure that page is friendly to people who might hit your site for the very first time from a platform. You could even make separate landing pages for each platform, as users from Instagram might be expecting something different than Pinterest users.

Pin a List-Building Post to the Top of Your Profile

Twitter and Facebook will allow you to pin posts to the top of your feed. I pinned a tweet about my Free Email Course (a free course sent via autoresponders when people sign up), and the interaction far outweighs my norm.

Use Platform-Specific Tools

You can also utilize Twitter cards (read this tutorial to get started) or Facebook ads (read this helpful post to guide you) to help you be more effective on those platforms with your list-growth.

Optimize Your Books

Much of the indie writer community has relied on this method to grow their email list. In the typical Nick Stephenson Reader Magnet method, you offer a permafree book on Amazon with a link inside the book for another free book if someone joins your email list. (Yes, that’s two books you’ll give away.)

While this works, the idea is daunting to many authors with only one book or two books total. Some authors don’t want to give away free books. Period.

Even if you aren’t following that typical reader magnet strategy, you can still optimize your books for email signups. Consider these options within your books:

Put a full page in the front or back advertising your freebie, with a link to a landing page

Mention and link to your email list in your bio or introduction

Create a related freebie and link to it throughout the book

As an example of this last option, I created a printable workbook to go along with my ebook Email Lists Made Easy for Writers and Bloggers. I mentioned the free workbook in the introduction with a link to a landing page to sign up. I also ended every chapter linking to the landing page and giving a call to action for readers to do that chapter’s work in the workbook. This has been converting at just over 20 percent. This means I’m growing my list even from a paid product!

Online Events

Webinars and virtual summits have been all the rage the past few years and continue to be a great source for list growth. These may be outside of your comfort zone, but don’t have to be an insurmountable task. You can code a simple webinar onto your own webpage or consider if speaking at or running a virtual summit might be a realistic option for you (read this post to see what’s involved in creating a summit). Each of these kinds of events also requires promotion on social media the same way you would promote your email list or a blog post, but can result in a surge in subscribers.

The thing to remember about list-growth is that it’s a mindset. If you want to grow your list, you constantly have to be thinking about list growth. Experiment with signup options and change out the subscribers forms on your sites every few months. Plan ahead to try a webinar or consider writing a guest post on a site that allows you to include a content upgrade within the post. Plan realistic goals for growth and write up a strategy for the coming months to hit your target.

The thing to remember about list-growth is that it’s a mindset. If you want to grow your list, you constantly have to be thinking about list growth. Experiment with signup options and change out the subscribers forms on your sites every few months. Plan ahead to try a webinar or consider writing a guest post on a site that allows you to include a content upgrade within the post. Plan realistic goals for growth and write up a strategy for the coming months to hit your target.

Above all, don’t be discouraged by unsubscribes or someone else’s numbers. Remember that your subscribers (whatever that number is) make up a room full of people waiting on a word from you.

For more insight into sending meaningful email, check out Email Lists Made Easy.

July 20, 2016

3 Myths About the MFA in Creative Writing

Photo credit: ironypoisoning via Visual Hunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from DIY MFA by Gabriela Pereira (@DIYMFA), just released from Writer’s Digest Books.

Most writers want an MFA for one of three reasons: They want to teach writing, they want to get published, or they want to make room in their life for writing. It turns out these reasons for doing an MFA are actually based on myths.

Myth 1: You Need an MFA to Teach Writing

Many writers get the MFA because they think it will allow them to teach writing at the college or graduate level. Once upon a time this might have been the case, but these days so many MFA graduates are looking for jobs and so few teaching positions exist, that it’s a challenge to get a teaching job with a PhD, much less with a terminal master’s degree. The writers who do manage to snag a coveted teaching position are often so overwhelmed with their responsibilities that they have to put their own writing on the back burner. While in the past an MFA may have served as a steppingstone to becoming a professor, it’s not the case anymore.

More important, many teachers in MFA programs do not have that degree themselves. Some professors are successful authors with prominent careers, while others are publishing professionals who bring the industry perspective to the courses they teach. This goes to show that the MFA has little impact on a writer’s ability to teach writing. Being a successful author or publishing professional is much more important.

Myth 2: The MFA Is a Shortcut to Getting Published

No agent will sign you and no editor will publish your book based on a credential alone. You have to write something beautiful. If you attend an MFA program and work hard, you will become a better writer. And if you become a better writer, you will eventually write a beautiful book. An MFA might help you on your quest for publication, but it’s certainly not required. After all, many writers perfect their craft and produce great books without ever getting a degree.

Ultimately getting published is a matter of putting your backside in the chair and writing the best book possible. For that, you don’t need an MFA.

Myth 3: An MFA Program Will Force You to Make Writing a Priority

If you can find time to write only by putting your life on hold and plunging into a graduate program, then your writing career isn’t going to last very long. Only a small percentage of writers can support themselves and their loved ones through writing alone. This means you must find a balance between your writing and the rest of your life.

Even within your writing career, you must become a master juggler. Forget that glamorous image of the secluded writer working at his typewriter. These days, writing is only a small piece of the writer’s job. In addition to writing, you must promote your books, manage your online presence, update your social media … and likely schedule these tasks around a day job, a family, and other responsibilities.

The danger with MFA programs is that they train you to write in isolation but don’t always teach you how to fit writing into your real life, or even how to juggle writing with all the other aspects of your writing career. Not only that, but external motivators like class assignments or thesis deadlines don’t teach you to pace yourself and build up the internal motivation you need to succeed in the long-term.

Genre Writing in MFA Programs

Most MFA programs focus on literary fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. While these are noble areas of literature, they cover only a tiny slice of the wide and diverse world of writing. Heaven forbid a writer in a traditional MFA program produces something commercial—or worse, genre fiction. While a handful of MFA programs allow writers to study genre fiction or children’s literature, the majority still focus on literary work alone. If you want to write genre fiction, commercial nonfiction, or children’s books, you likely will not learn much about them in your MFA courses.

Writers of genre and commercial fiction are among the most dedicated, driven writers I know. They take their craft seriously and work hard to understand the business side of the publishing industry. In addition, a vast number of associations, conferences, and guilds are dedicated to specific genres or commercial writing. Literary writers are not the only ones who crave knowledge and community. Commercial and genre writers want it, too.

This is why I created DIY MFA: to offer an alternative for writers who do not fit the strict literary mold of the traditional MFA system.

Should You Pursue an MFA?

MFA programs are not a bad thing. In fact, they are exceptional at serving a small and very specific group of writers. If you write literary fiction, creative nonfiction, or poetry, and if you thrive in a formal academic environment, then the traditional MFA is a great option. If you can afford the tuition without taking out loans, and if you have the time to make the most of the experience, then you are one of those ideal candidates for graduate school.

One reason I am extremely grateful for my own MFA is that it gave me the opportunity to work with several phenomenal teachers. I studied YA and middle-grade literature with the brilliant David Levithan. The legendary Hettie Jones was my first workshop teacher. I worked closely with Abrams publisher Susan Van Metre, who served as my thesis advisor and mentor. These experiences were invaluable, and at the time I didn’t think I could make connections with such literary luminaries any other way. Now I know, however, that you can make connections and find great mentors without attending an MFA program.

The “Do It Yourself” MFA

As an MFA student, I discovered the magic equation that sums up just about every traditional MFA. The Master in Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing is nothing more than a lot of writing, reading, and building community. In the workshops, you exchange critiques with other writers and work toward a manuscript that becomes your thesis project. Most programs also require you to take literature courses both in and outside your chosen area of literature. Finally, you are asked to attend readings or talks by other writers—to build your personal writing community. To create a personalized, do-it-yourself MFA, you have to find a way to combine these three elements.

Write with focus. You have to commit to a project and finish it. In traditional MFA terms, this project is your thesis, and it’s a crucial part of your development as a writer. But you don’t need to complete a thesis to get this experience; you just need to finish and polish a manuscript. While you can feel free to play and explore early on, you must eventually choose a project and see it through from beginning to end. When you write with focus, you write with a goal in mind.

Read with purpose. This means reading with a writer’s eye. If you’re like me, you were a bookworm long before you could hold a pencil in your hand. Writers love books. In fact, many of us become writers so we can create the very books we love to read.

Reading for pleasure is wonderful, and it certainly has its place. Reading with purpose is different: It is reading in a way that serves our writing. It’s not just about finding out what happens in the story; it’s about learning how the author pulls it off. Reading this way isn’t just an intellectual exercise. When we read with purpose, we examine how an author crafts a story so we can emulate those techniques in our own work.

Build your community. In the traditional MFA, building a community happens organically. You meet fellow writers in your workshops and literature courses. You go to readings and conferences to connect with authors. You attend a publishing panel and learn about the industry. The community element is baked into the MFA experience.

When working on your own it takes more effort, but you will learn how to find critique partners and fellow writers to support you on your journey. You’ll discover conferences and associations that will help you navigate the publishing industry and the business side of writing. Finally—and perhaps most important—you will also learn ways to find and connect with your readers.

When working on your own it takes more effort, but you will learn how to find critique partners and fellow writers to support you on your journey. You’ll discover conferences and associations that will help you navigate the publishing industry and the business side of writing. Finally—and perhaps most important—you will also learn ways to find and connect with your readers.

To learn more about crafting your own customized MFA experience, sign up for the DIY MFA newsletter, and check out the new book, DIY MFA.

July 19, 2016

5 Ways to Develop Your Writer’s Voice

by Andy Morffew | via Flickr

Today’s guest post is from author Jennifer Loudon (@jenlouden).

Developing your writer’s voice requires you to know yourself and reveal that self in your writing: this is who I am and this is what I care most about.

To develop your voice you must investigate and own your singular way of noticing your world, and then practice and hone your singular way of capturing that noticing. You must step away from other people’s opinions and stories, from what you may think you should sound like, and get curious about your opinions, your stories, your experiences.

Avoid doing this work and you may well find your writing stalls out and begins to feel flat, even pointless. Turn toward developing your voice and you may find big dividends: more flow and energy, more readers, more publishing and other opportunities, and most of all, more sincere and satisfying work.

So how do you get your voice development cooking? Here are five time-tested ideas you may find useful.

1. Be Devoted to Paying Attention

Cartoonist, podcaster, and teacher Jessica Abel advises her students to “Pay attention to what you pay attention to,” while Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gassett said, “Tell me to what you pay attention and I will tell you who you are.”

What lights you up? What drives you batty? What problem do you have a solution for? What images compel you? What sentence structures make your heart zing? What words do you love—or hate?

All of these can be sources of your voice, but you must pay exquisite attention to them or they poof! disappear. Cultivate noticing what you notice, noting it, and valuing it even though it makes no sense (yet). Make space to these clues by taking a sabbatical from social media and Netflix (just an evening works wonders). Boredom and silence are your voice’s ally as you recognize and heed what captures your mind and heart.

2. Show Your Mistakes

Your voice won’t fully mature if you edit as you write. One of my writing retreat participants, Erin, said:

“My writing process hinged on editing. I wanted to say things perfectly, compulsively. My creative process consisted of a flash of inspiration and then the editing of that flash of inspiration repeatedly and compulsively until I was bored and it was boring. The hard work for me is to write through the bad.”

Try generating new material without deleting as you go. Leave a string of your not-quite-right words and ideas. What happens if you erase your first inkling? You interrupt the flow that will soon lead you to what you really want to say. Tidying as you go cuts off your process. Learn to tolerate seeing the mess so your voice has room to grow and permission to show itself.

3. Focus on Your Reader—or Not

Having one specific reader in mind can be a tremendous way to focus your work. For example, writing this post, I have a writing student in mind who’s struggling with bland writing because she’s hampered by too much writing advice. She’s helping me focus on the most salient ideas rather than skittering all over the place. However, if I think about you, a reader I don’t know, I freeze up, thinking, What should I write?

Each project invites you to decide when to have a reader in mind. If you’re writing an article for LinkedIn Pulse about ways to deal with a difficult but valuable employee, it might be a huge time saver to imagine your friend who works in HR. But if you find yourself editing, parsing words, shying away from the more complex or messy thoughts because your reader is looming over you, put her out of the room—for now. Bring your reader in on the second or even third draft. Sometimes your voice needs some privacy to reveal itself.

4. Feed Your Envy

The poet Billy Collins spoke at the White House Poetry Student Workshop about how to find your voice. He believes you must “Read widely, read all the poetry you can get your hands on. And in your reading, you’re searching for something. Not so much your voice. You’re searching for poets that make you jealous.”

Then he suggests you key into these poets, mimicking the ones you admire until their influences weave and combine into something new: your voice.

I agree with Mr. Collins, but only if you combine this kind of reading and copying with being devoted to paying attention. You need inner and outer influences to support your voice’s development.

Here are two specific ways to use envy to strengthen your voice:

When you read something that makes you want to give up writing because it’s so damn good and you don’t think you’ll ever be able to make that kind of magic, write out the passage you love in longhand—it takes longer and you learn more by doing so. Then ask yourself, “Why do I love this so much?” Discuss with a writer friend. Be prepared to struggle mightily to understand why. Bonus: do this with a piece of writing you hate—sometimes even more illuminating.

Create a lexicon for a specific project. If you’re writing a novel set in the southwest desert, gather plant names, geologic formations, types of clouds. Search poetry, history, guide books, and novels. Write down only what attracts you. This is nourishment for your voice and your project! (Hat tip to Seattle writing teacher Priscilla Long for this idea.)

5. Read Aloud

You can’t recognize and then strengthen your voice if you don’t hear it—and hearing it in your head isn’t the same as hearing it spoken aloud. Get in the habit of reading what you write out loud. I print and read everything before I send something out and also whenever I’m feeling all snarled up in my organization.

Want to accelerate your voice development? Read out loud to another person without any feedback. This is utterly maddening to your inner approval junkie: “But what does she think about my writing?!?” The magic comes because you turn toward yourself and listen for where you are being true to what you wanted to say and where you’re skirting the truth, where you dug deep and where you skimmed the surface, settling for clichés. Of course, there are plenty of times when getting specific feedback from other writers is useful—but not when it comes to honing your voice.

Which of these ideas will you try out in your next writing session? Choose one idea from this post to put into action in the next twenty-four hours, then come back here and tell me what you discovered.

Claiming and sharing your voice will challenge you. You may feel resistance and fear because you’re leaving known territory. Plus, it’s more work! But your writing will be truer, will affect your reader more deeply, and you’ll be more satisfied with the process, and perhaps even the result. It may well require more of you than you could imagine (I know it does me) but when I make the effort, I end a writing session tired but oh so much more satisfied.

May you give voice to the ideas and stories that only you can write.

July 18, 2016

Learn an Overlooked Writing Skill: Free Training on July 27

Writing a compelling book is the most important step toward the goal of a successful writing career. But selling your books can be a challenge no matter how strong your story may be.

When it comes to a sustainable author career, copywriting is a skill even I could improve upon. (Since 2011, I’ve been writing about the importance of this skill.)

Bryan Cohen is a Chicago author who has written more than 40 books, and 300 book descriptions for other authors. He teaches thousands of writers at all levels how to improve their marketing skills.

Bryan has agreed to team up with me on a free training for my readers on Wednesday, July 27, at 2 p.m. Eastern. This live training will teach you simple systems to write sales copy that’s as impressive as your story; it will help you improve your book descriptions, advertising copy, and emails to readers.

When you show up live, you’ll be able to participate in a Q&A session with Bryan to answer all your copywriting questions. If you can’t attend live, a recording will be made available for you to review after the session.

Near the end of the session, he’ll tell you more about his fee-based course on copywriting that provides more intensive and comprehensive instruction. Full disclosure: If you register, I end up receiving a percentage of your course fees. I recommend his instruction because I trust it and think copywriting is one of the most overlooked skills for writers.

July 13, 2016

Internal Dialogue: The Greatest Tool for Gaining Reader Confidence

Photo credit: chuddlesworth via VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-ND

The following post by author Elizabeth Sims (@ESimsAuthor) is an excerpt from the newly released Crafting Dynamic Dialogue from Writer’s Digest Books.

Not long ago, one of my elderly neighbors lost several thousand dollars to a con artist. A stranger phoned with a convincing sob story that ended in a plea for money. My neighbor actually filled a paper lunch sack with twenty-dollar bills, drove to a nearby grocery store, stashed the bag behind a vegetable bin as directed, and left. Even when a friend explained that it was a trick, my neighbor was serene, believing he had done a service for someone in need.

The best con artists don’t begin by asking for your confidence—they give you theirs first. Here’s my story. I want you, you especially, to hear this. The request for help comes later. There’s the short con—one quick deception and out—and the long con, which takes time and patience to execute. But before either compassion or greed can be exploited, the mark must feel something for the con artist.

When you think about it, what is fiction but one beautiful long con? The reader—the mark—opens a book craving a good story, thirsting to be part of something special. We, as writers, do everything possible to gain the trust of our readers so we can entertain, shock, delight, and amuse them all the way to the end.

And the greatest tool for gaining reader confidence is internal dialogue. Because when a character reveals his thoughts, he’s confiding in the audience. I’m counting on you to understand me—and possibly even help me understand myself. Suddenly readers are in the thick of it; they feel involved and invested. They have some skin in the game.

What Exactly Is Internal Dialogue?

Simply, it’s the inner voice of a character. Which is, frankly, a very metaphysical subject. In most modern cultures—and, consequently, most modern literature—there’s a dichotomy within the self: there’s an I and a Me.

I like my eyebrows.

I have to be strict with myself when it comes to pecan pie.

Internal dialogue is the manifestation of this in fiction. And because it presents the most intimate thoughts and realities of your characters, it is beyond elemental: Internal dialogue is the marrow of your story.

For inexperienced writers, internal dialogue can be confusing, because a character’s inner voice can take endless forms. How does one properly represent it? The truth is, there are really very few rules for using internal dialogue. That’s freeing. All you need is a basic understanding of the subject, and some reference points.

With internal dialogue, you can:

Establish your characters and their unique voices.

Show the difference between what a character thinks versus what she says or does. This can fuel both tragedy and comedy.

Trace a character’s growth and development, or the opposite: a character’s degeneration. Change is the name of the game.

Develop your plot. A shift can become clear in a word or two.

Reveal things below the surface: pain, secrets, hopes, fears …

Create and develop suspense. Especially when the reader knows more than the character, the reader can be worried about some impending event or consequence.

Change the subject. No matter what’s going on, a character’s thoughts can suddenly drive your story in a new direction.

Reveal a character’s opinions. This one’s always fun.

Describe. A character can look around and comment on his surroundings; he can observe and analyze.

Develop and reveal character motivation. Why are they doing what they’re doing?

Render reflection. Let your character think through a problem or process an event to whatever degree she’s capable of. A character can be a tad less smart than the reader, thus permitting the reader to feel on top of things. Reflection can also be used to:

Adjust the pace. After a spate of action, let your character(s) pause and reflect. is can even happen while things in your story literally are still in motion—say in a speeding subway train. But even so, it will slow things down and let the reader absorb what just happened.

The Form and Format of Internal Dialogue

Internal dialogue typically takes three basic forms: first-person narration, third-person narration, and direct thought-speech. The latter is my term for thoughts expressed as if directly spoken to the reader, usually without attributors like “I thought.” Can narration be internal dialogue? The boundaries are squishy at best, as you will see, so don’t worry about it.

Then there’s the issue of tense. Skim through today’s bestseller lists, and you’ll find the majority of internal dialogue written in present tense, no matter whether the rest of the work is in past. This technique works well, but isn’t the only choice.

As for format, the only rule is to avoid quotation marks, single or double, as they’re associated with spoken-aloud dialogue and can confuse the reader. It used to be the convention to put inner thoughts in italics. I’ve done so in my fiction. Now the trend seems to be to keep everything in roman text, the idea being that italics are intrusive and unnecessary.

For both form and format, you can select something that feels right for you and your manuscript’s style and voice.

Read closely to distinguish the differences in the six versions of this passage:

Saturday night came, and still Sheila didn’t call. Marco sat at the window, drumming his fingers on the gritty sill. He felt like robbing a liquor store. Would a knife be sufficient? He didn’t know. [Entire passage, including inner voice, is third person, past tense.]

Saturday night came, and still Sheila didn’t call. Marco sat at the window, drumming his fingers on the gritty sill. I should hold up that liquor store tonight, I really should. Be something to do, anyway. I have my knife. [Narrative is third person, past tense; inner voice is first person, present. And the inner voice is rendered in direct thought-speech.]

Saturday night came, and still Sheila didn’t call. Marco sat at the window, drumming his fingers on the gritty sill. I should hold up that liquor store tonight, I really should. Be something to do, anyway. I have my knife. [The identical passage as above, with Marco’s thoughts in italics.]

Saturday night came, and still Sheila didn’t call. I sat at the window, drum- ming my fingers on the gritty sill. I should hold up that liquor store tonight, I really should. Be something to do, anyway. I have my knife. [Narrative is first person, past tense. The inner voice, in direct thought-speech, is first person, present.]

Saturday night came, and still Sheila didn’t call. Marco sat at the window, drumming his fingers on the gritty sill. I should hold up that liquor store tonight, I really should, he thought. Be something to do, anyway. He had his knife. [Narrative is third person, past tense. The inner voice is first person, past (though verging on present), and the narrative resumes in third person, past, in the final sentence.]

Saturday night comes, and still Sheila doesn’t call. I sit at the window, drumming my fingers on the gritty sill. I should rob that liquor store tonight, I really should. Be something to do, anyway. I have my knife. [Everything is first person, present.]

Any of these forms are correct, and they all have slightly different flavors—some seem more formal, some less. First person always reads as more informal and immediate. Just be as consistent as you can, once you’ve made your choice.

Pitfalls to Avoid

Making a character’s inner voice into a sarcastic wisecracker who won’t shut up. Such a voice can be entertaining, but only if used sparingly. When your beta readers start to groan because they know exactly what the inner wiseass is going to say, that’s when to dial it back.

Head hopping. Reserve internal dialogue for very few characters. Many writers successfully do internal dialogue for just one character— their protagonist.

“… I thought to myself.” As a writing coach, I’m on the alert for this construction, which screams rank amateur. Who but oneself does one think to?

Telling huge hunks of backstory via having a character “think about” or “remember” it.

Putting in anything that doesn’t serve the story. If it’s important that your protagonist dithers over whether to buy the store brand bleach, fine, but if it’s not relevant, just let him buy bleach and get on with it.

Examples of Internal Dialogue

The encounter, though, had bruised her. Gavin was the first person, she thought, that I was ever really frank and honest with; at home, there wasn’t much premium on frankness, and she’d never had a girlfriend she was really close to, not since she was fifteen.

In this passage from Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel, she plays with internal dialogue free and easy, switching from third person to first and back again. The reflective passage gives us a sense of the character Colette’s loneliness and inner pain. We also get the hint that Colette is somewhat limited, not resourceful, not very strong, and thus motivated to subsume herself by becoming an assistant to a more prominent—and dominant—person.

… On my way into the Chinese cleaners I brush past a crying bum, an old man, forty or fifty, fat and grizzled, and just as I’m opening the door I notice, to top it o , that he’s also blind and I step on his foot, which is actually a stump, causing him to drop his cup, scattering change all over the sidewalk. Did I do this on purpose? What do you think? Or did I do this accidentally?

In this passage from American Psycho by Brett Easton Ellis, the main character, the psychopathic Patrick, is presented in all his shockingly casual cruelty. We see that he is contemptuous and selfish. We get his sarcastic inner voice in the direct question to the reader—What do you think? Patrick’s personal style is brusque and immediate, and we don’t need a crystal ball to perceive that this morsel of brutality is but a taste of what’s to come. The reader lives in suspense to the end.

Also she loved her house. Across the creek was the Russian church. So ethnic! That onion dome had loomed in her window since her Pooh footie days. Also loved Gladsong Drive. Every house on Gladsong was a Corona del Mar. That was amazing! If you had a friend on Gladsong, you already knew where everything was in his or her home.

Jeté, jeté, rond de jambe.

This passage from “Victory Lap” by George Saunders reveals a young girl’s stream of consciousness as she bops around the house, alone. We see Alison’s exuberant spirit as she describes her environment and executes ballet moves; we understand that she lives in a bland subdivision; with the mention of the creek we literally get the lay of the land; we’re aware of an unusual neighboring structure. In this short story, Saunders portrays Alison’s voice with precision, and as we ingest her unspoiled happiness, we also know that we’re reading a story—and in stories, things happen and things change. This inherent suspense suffuses all of Saunders’s tales.

Build Your Skill at Internal Dialogue

A good way to develop your feel for internal dialogue is to get in touch with your own internal dialogue—the stream of consciousness that flows through your head, sometimes annoyingly, sometimes quietly and productively.

Take fifteen minutes and simply write what you’re thinking. If you stall out, remember some recent problem or bit of family drama, and write your internal dialogue on that.

Strive to render your thoughts as realistically as you speak.

Strive to render your thoughts as realistically as you speak.

Write it. How did it feel? Read it over. What’s it like? What do you see? When you turn to your fictional characters, remember what it felt like to write “out of your head.”

For more advice on dialogue—both spoken and internal—check out the Crafting Dynamic Dialogue from Writer’s Digest Books.

July 11, 2016

If You Just Keep Writing, Will You Get Better?

Photo credit: thart2009 via Visualhunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post is from author Barbara Baig.

How do certain people become really great at what they do?

That’s the question psychology professor Anders Ericsson has been exploring for his entire career. Now, in his new book, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, co-written with science writer Robert Pool, Ericsson reveals the answer.

If you’ve heard of Ericsson, it’s probably because his research and ideas have been featured in many articles and books, notably Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and Geoff Colvin’s Talent Is Overrated. In Peak, he finally gets to explain things his own way.

In very readable prose, Peak describes how Ericsson and his colleagues have studied top performers in many fields, and it shows how all of these performers use the same kind of training methods. Peak is not designed specifically for writers, but any aspiring writer who reads it and (even more important) makes use of the training principles the book explains

will find his or her abilities dramatically improved.

How can this be? How can a training approach used by top golfers, divers, ballet dancers, surgeons, and many other people possibly help writers?

The answer is simple: it’s all in our brains.

When it comes to becoming better writers, most of us make three assumptions:

The answer is simple: it’s all in our brains.

When it comes to becoming better writers, most of us make three assumptions:

Each of us is born with a certain innate potential for achievement: We call it talent. Getting better at what we do is simply a matter of fulfilling that inborn ability.

To get better at what we do, we just need to keep doing it.

Improvement depends on how much effort we put in. If we’re not improving, we’re just not trying hard enough.

These assumptions are so common you might not even realize you hold them. But they share something with many other widely held assumptions: they aren’t true.

Even brain scientists used to believe that each person’s brain—and, therefore, his abilities—were fixed at birth. But since the 1990s brain scientists have discovered that the human brain, even the adult brain, is far more adaptable than anyone ever imagined. They call this ability of the brain to change in response to challenges its plasticity, a quality that (barring injury or illness) everyone’s brain possesses. It’s the ability of our brains to change—not our innate talent—that allows us to learn and develop new skills.

“Just keep writing, you’ll get better”: this piece of writing advice pervades the internet. Sadly, it’s completely wrong. In their studies of experts, Ericsson and his colleagues have shown that none of them achieved mastery simply by doing the same thing over and over.

And while effort is certainly important, effort by itself will get us nowhere. What we need, Ericsson explains, is the right kind of training, the kind of training that creates experts in any field. He and his colleagues named this kind of training deliberate practice. Well, sure: practice. We all know what that is. Or do we?

When most of us think about practice, we’re imagining what Ericsson calls naive practice, the kind of repetitive action we do to learn a skill and then put it on automatic pilot. We learn a lot of things this way—cooking dinner, for instance, or driving a car. The trouble with this kind of practice is that it will never help us improve our skills. For that, we need a different kind of practice, one Ericsson calls deliberate practice. Deliberate practice, he tells us, will harness “the adaptability of the human brain to create, step by step, the ability to do things that were previously not possible.” With this kind of practice, we literally build areas of the brain involved in writing, thereby increasing our own “talent” and making ourselves better writers.

This particular kind of practice—deliberate practice—is not easy, and it’s not fun. It requires setting goals for our practice sessions, maintaining focus as we practice, getting feedback on our practice, pushing ourselves out of our comfort zone, developing effective mental representations of the skills we’re practicing, and learning from models of excellence. Peak provides details of all of these elements of deliberate practice, and lots more, giving us a totally new approach—new for writers, but well-proven in other fields—to developing our skills.

So, how might we use this approach? First, we have to consider our writing skills: Which ones do we have? Which ones do we lack?

Suppose, for instance, that we want to improve our sentences; suppose that we choose to work on prepositional phrases. First, we need to be sure we know what a prepositional phrase is (effective mental representation); we’ll probably have to look that up and provide ourselves with a list of prepositions to use in our practice. For our first practice session, perhaps our goal is to write a number of sentences and use every preposition on the list. Getting feedback on this practice is easy: we just compare the prepositions we’ve used with those on the list. (If we’re not sure we’ve used a preposition correctly, we’ll have to check that out.)

After we’ve done some more practices like this, we can push ourselves out of our comfort zone by setting stricter requirements, perhaps insisting on three prepositional phrases per sentence, or beginning and ending a sentence with a prepositional phrase. We can also turn to our best teachers, our favorite writers, and copy down sentences from their work that demonstrate a mastery of prepositional phrases. Then we imitate how our writers have used this technique and compare our efforts to the originals.

Is this kind of practice a lot of work? Yes, it sure is. But if you practice this way, with any writing technique, you will build your skills faster and more effectively than you can possibly imagine. And then, you will own those skills, you will be able to use them at will, and you will develop an unshakeable confidence in your ability to do whatever you want on the page.

I can speak from personal experience here. Some years ago, I taught myself all the techniques of diction and syntax I present in my latest book, Spellbinding Sentences. Even more important, all those months of practice, all that training, transformed me into a writer with skills she can depend on.

But don’t take my word for it. Get yourself a copy of Peak. Read it carefully and figure out how you can use the principles of expertise acquisition Ericsson describes. Then make practice an ongoing part of your writing routine. The  right kind of practice, Ericsson tells us (along with perseverance and ongoing effort), can change our brains. It can turn us into the writers we’ve always wanted to be. It might even change our lives.

right kind of practice, Ericsson tells us (along with perseverance and ongoing effort), can change our brains. It can turn us into the writers we’ve always wanted to be. It might even change our lives.

For more from Barbara Baig, check out Spellbinding Sentences: How to Achieve Excellence and Captivate Your Readers.

July 7, 2016

5 Steps to a Killer Book Talk

Photo by Joe Mabel

Today’s guest post is by Kate Raphael (@katrap40), author of the award-winning Murder Under The Bridge: A Palestine Mystery.

Every debut author dreams of the moment when she stands up in front of a crowd of admiring fans and talks brilliantly about her new book.

Yet too few of us actually spend enough time planning that talk. Many new authors spend a lot more time on the logistics of their launch events, getting the word out, even shopping for signing pens, than on what they are going to say.

That’s a huge mistake.

We’re not only launching our books, we’re launching ourselves as authors. An engaging talk can get you invited to be on panels or radio shows. That’s happened to me a couple times. But it takes as much work as writing a guest blog or an op-ed. Almost no one can extemporize well all the time, or even very much of the time.

I will venture an untested statistic: at least 90 percent of great speakers, from President Obama on down, are really great writers, or have great writers working for them, or both. The more unscripted they sound, the longer they likely worked on what they’re saying. They also have teleprompters and we don’t, so we have to work even harder to get that brilliantly off-the-cuff sound.

Preparation is respectful.

I think one thing that keeps authors, especially women authors, from preparing their talks is fear of appearing self-important. It’s easier to think of ourselves giving a party. But people have a lot of choice about what to do with their time. No one is going to resent having to listen to a lively, well-crafted, funny, surprising talk about your book.

People don’t go out to an author event for the reading. If they just want to know what is in the book, they can buy it and enjoy it in the comfort of their easy chairs. They are there for the value added, which is not the mediocre champagne. It’s the story behind the story, the well-chosen information that makes the reading come alive.

Speaking is writing; writing is editing.

The other reason people don’t prepare well enough is that we all know our books better than we know our lovers. We talk about them all the time, probably too much.

One of the counterintuitive things I have learned as a radio host is that the better I know the subject, the more I need to prepare. If I don’t know much about a subject, I can just say everything I know. If I know a lot, I have to do a lot of editing. It’s easy to forget that things that seem very basic to me probably aren’t. I need to put myself into the mindset of the listeners who are least familiar with the subject and ask, “What will they want to know?”

If your event is anywhere but in your house, if it was advertised in even one newsletter, you never know who will show up. At one of my readings, there were a couple people who were walking by and the title of my book grabbed them; at another a woman told me she had heard me on the radio two hours earlier and decided to go. Another author I know was shocked that seven people she didn’t know appeared at an out-of-town event because a friend of hers told them about it.

5 steps to a great book talk

1. Write out what you’re going to say. Write about 10 minutes of talk, 5 minutes of reading, 5 to 10 more minutes of talking and another 5 minutes of reading. Time it. Humor is wonderful, but if it’s not your style, don’t use it. Heartfelt is just as good or better.

2. Read your talk out loud over and over until you feel really comfortable with it.

3. Take your written talk and turn it into notes. Write down a few words that will remind you what’s in each paragraph. Get onstage with your notes. Print them out in large type or use an electronic device and enlarge the text.

4. Some beautiful writing is not suitable for reading aloud. Shorter sentences with few dependent clauses work best. Try to read passages that are not packed with description and don’t have too many characters. Dialogue, since it’s speech translated to the page, is generally easy to translate back into speech.

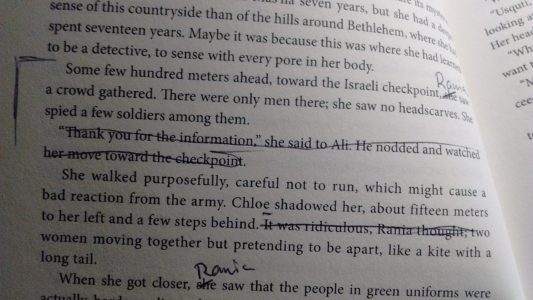

Vary the tone of the passages you choose (light, heavier, suspenseful, romantic). Don’t hesitate to edit for easier reading. If you stumble over a word or phrase twice in practice, take it out. Here is what my reading copy looks like:

5. Think about what questions people are most likely to ask and practice your answers. Have a few points you want to make during the Q&A and be prepared to work your way around to those points even if the questions are not asked directly. If you get an off-the-wall question, you can use it as an opportunity to make one of your prepared points.

Recently, I interviewed Claudia Six, author of Erotic Integrity: How to Be True to Yourself Sexually, along with Brooke Warner, author of Greenlight Your Book. I asked them why it takes so long to bring a book into the marketplace, and Brooke talked about the pre-sale and pre-publicity process. Then Claudia chimed in, “It’s kind of like having erotic integrity—you’ve got to own that you’ve written this book and you have something to say.”

I thought, “She is going to do well because she can turn any question into a chance to talk about her book.” That’s a great skill to cultivate.

To find out more about Kate Raphael and her book, visit her website.

July 6, 2016

5 Pieces of Writing Advice You Should Ignore

Today’s post is an excerpt adapted from Just Write by James Scott Bell (@jamesscottbell), recently published by Writer’s Digest Books.

Some time ago I cheekily posted on my group blog, Kill Zone, the three rules for writing a novel. The post produced a spirited discussion on what is a “rule” and what is a “principle,” but by and large there was agreement that these three factors are essential to novels that sell:

Don’t bore the reader.

Put characters in crisis.

Write with heart.

But here I’d like to discuss some writing advice writers would do well to ignore.

Where does such advice come from? I have a theory that there is a mad scientist in Schenectady, New York, who cooks up writing advice memes and converts them to an invisible and odorless gas. He then secretly arranges for this gas to seep into critique groups across the land, infecting the members, who then begin to dispense the pernicious doctrine as if it were holy writ.

I now offer the antidote to the gas.

1. Don’t Start with the Weather

This meme may have started with Elmore Leonard, who once dashed off a list of “rules” that have become like sacred script for writers. If his advice were, “Don’t open a book with static, flat descriptions,” I would absolutely agree.

But here is why the rule is baloney: Weather can add dimension and tone to the opening disturbance. If you use it in that fashion, weaving it into action, it’s a fine way to begin.

Look at the opening of Bleak House by Dickens. Or the short story “All at You Love Will Be Carried Away” by Stephen King. Or the quieter beginning of Anne Lamott’s Blue Shoe. All of them use weather to great effect. Here’s a Western, Hangman’s Territory, from Jack Bickham:

The late spring storm was breaking. To the east, boiling blue-gray clouds moved on, raging toward Fort Gibson. To the west, the sun peered cautiously through a last veil of rain, slanting under the shelf of clouds and making the air a strange, silent bright yellow. The intense, muggy heat of the day had been broken, and now the early evening was cool and damp, and frogs had magically appeared everywhere in the red gumbo of the Indian Nations.

Eck Jackson threw back the heavy canvas under which he had been waiting. His boots sank into the red mud as he clambered out of his shelter between two rocks and peered at the sky.

If you think of weather as interacting with the character’s mood and emotions, you’re just fine to start with it.

2. Don’t Start with Dialogue

Starting with dialogue creates instant conflict, which is what most unpublished manuscripts lack on the first pages. Sometimes this rule is stated as “Don’t start with unattributed dialogue.” Double baloney on rye with mustard. Here’s why: Readers have imaginations that are patient and malleable. If they are hooked by dialogue, they will wait several lines before they find who’s talking and lose absolutely nothing in the process.

Example:

“TOM!”

No answer.

“TOM!”

No answer.

“What’s gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!”

No answer.

The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room …

—Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

3. No Backstory in the First 50 Pages

If backstory is defined as a flashback segment, then this advice has merit. Readers will wait a long time for backstory information if something compelling is happening in front of them. But if you stop the forward momentum of your opening with a longish flashback, you’ve dropped the narrative ball.

However, when backstory refers to bits of a character’s history, then this advice is unsound. Backstory bits are actually essential for bonding us with a character. If we don’t know anything about the characters in conflict, we are less involved in their trouble. (Read Koontz and King, who weave backstory masterfully into their opening pages.)

I’ve given writing students a simple guideline: three sentences of backstory in the first ten pages. You may use them together or space them apart. Then three paragraphs of backstory in the next ten pages, together or apart.

I’ve seen this work wonders for beginning manuscripts.

4. Write What You Know

Sounder advice is this: Write who you are. Write what you love. Write what you need to know.

5. Don’t Ever Follow Any Writing Advice

A few literary savants out there may be able to do this thing naturally, without thinking about technique or craft, and those three people can form their own group and meet for martinis.

Every other writer can benefit from time spent studying the craft. I’ve heard some writers say they don’t want to do that for fear of stifling the purity of their work. Some of them get a contract and their books come out in a nice edition that sells five hundred copies. And then the author gets bitter and starts appearing at writers conferences raging how there is no such thing as structure and writers have wasted their money attending the conference—that they all should just go home and write. (This has actually happened on several occasions that I know of.)

Every other writer can benefit from time spent studying the craft. I’ve heard some writers say they don’t want to do that for fear of stifling the purity of their work. Some of them get a contract and their books come out in a nice edition that sells five hundred copies. And then the author gets bitter and starts appearing at writers conferences raging how there is no such thing as structure and writers have wasted their money attending the conference—that they all should just go home and write. (This has actually happened on several occasions that I know of.)

Here is some advice: Don’t be that kind of writer.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out Just Write by James Scott Bell.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers