Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 114

June 21, 2017

The Challenge Faced by High-Quality Literary Journals

Over the last year, I have consulted with a range of literary journals at very different stages of development. Here’s a description of three of them:

One of the journals is a household name in the literary community with lots of subscribers—a strong brand in an enviable position.

Another has been around for several years and has established a good reputation. It’s doing well compared to its peers.

And the third has just released its first issue and is in the beginning stages of establishing a readership. It already has an admirable roster of contributors.

Each journal has a print subscription available, combined with some online offerings. They do things “right” and treat writers well. They engage with the literary community online. And they all suffer from the same problem: They distinguish themselves based on delivering high-quality literature.

Today, our problem is not finding more great things to read. It’s finding time to read the great many wonderful things that are published. If I stopped acquiring new reading material tomorrow—if I canceled all my subscriptions and turned off the internet—it would take years before I exhausted my supply of high-quality literature. Of course, this speaks to my many years of acquisition and the particular demographic I belong to, but the primary audience for high-quality literary journals is more similar to me than not.

Yet literary journals still operate and market themselves as if we were all starved for high-quality literature. Here’s a sampling of statements from a few well-known journals that describe what they publish or who they publish for:

Has a long tradition of cultivating emerging talent

Has published many great writers

For the many passionate readers

Publishes quality literature

Devoted to nurturing, publishing, and celebrating the best in contemporary writing

Finds and publishes the very best writers

These journals often take pains to emphasize, “Hey, we publish great writers, but we also publish undiscovered writers, too!” That’s really not any more distinctive than a dedication to high-quality literature. It’s just high-quality literature from a different source, while appearing perhaps more gracious, enlightened, or hard working. We look through our slush!

The result: These journals become indistinguishable from one another. To be fair, some have been around for decades and established their missions during a very different era. But now that we’re in a transformed publishing landscape, how many journals have meaningfully revisited what they do, why they do it, or who they’re doing it for? When they consider what distinguishes them from their peers, what is their answer? For many I’ve talked to, the answer is to reiterate “quality” and how that quality gets sourced. (For a publishing operation that has considered these questions meaningfully, take a look at this post from Coffee House Press.)

The bald truth is that no one cares about a high-quality literary journal, just as they don’t care about high-quality writing, as pointed out in this excellent piece by Hamilton Nolan:

Many writers believe that our brilliant writing will naturally create its own audience. The moving power of our words, the clarity and meaning of our reporting, the brilliance of our wit, the counterintuitive nature of our insights, the elegance with which we sum up the world’s problems; these things, we imagine, will leave the universe no choice but to conjure up an audience for us each day.

The problem is that nobody ever bothers to inform the audience. In fact, this imaginary Universal Law of Writing—“Make something great and the readers will come”—is false. … The audience for quality prestige content is small. Even smaller than the actual output of quality prestige content…

At the 2017 AWP, I sat on a panel about money and transparency, and someone in the audience asked how they could turn a publication based on volunteerism and free contributions into one that paid staff and writers. The short answer is you can’t unless readers are willing to pay and/or someone is willing to gift you into existence (e.g., grants or institutional support). There is no magic solution or sustainable model for the garden-variety “high-quality” literary journal. And whether readers pay you or patrons do, everyone looks for something deserving of their dollars, that has some kind of unique or inspiring place in the market, something beyond “quality.”

There is no meaningful audience to which you can market high-quality writing, at least outside of the AWP Bookfair. There may be a meaningful audience for high-quality writing that’s focused on a particular issue, cause, or movement. Or a publication that is unfailingly focused on promoting and celebrating a specific style of writing. (I remember fondly The Formalist, an erstwhile poetry journal that published only formal poetry.) But a publication that wishes to grow and flourish by positioning itself as a high-quality literary journal? As Nolan says, “I am here to tell you that it will not work.”

June 20, 2017

The Difference Between a Press Release and a Pitch (You Need Both)

Photo credit: floeschie via VisualHunt.com / CC BY

Today’s guest post is by Claire McKinney (@mckinneypr) and is an excerpt adapted from her new book, Do You Know What a Book Publicist Does?

There has been debate about press releases and whether or not they are obsolete. After all, when you can communicate in 140 characters, why do you need four to five paragraphs?

I have heard directly from book review editors that they toss the materials that come with review copies. I have also had a radio producer chastise me for mistakenly not sending a press packet with a book. Clients have asked me if press releases matter any more: “I mean, does anybody really read those things?”

The short answer is “yes”: there are media, booksellers, librarians, academics, etc., who do pay attention to an old-fashioned press release, and you have no way of knowing who is going to insist on having one and who isn’t. So, I wouldn’t throw out this tool just yet.

What a press release accomplishes

Below are the main reasons why you should write and include a release with your media kit.

1. The Core Message. Press releases are different from any of the other copy you will use to market your book. some of the words may be the same as what you have on the back of the jacket, but the release is supposed to achieve a few things, including delivering the newsworthy or unique aspects of what you are presenting; giving the reader an idea of why you would be a good interview subject; and a relatively brief synopsis of the best points of the book (or product, depending on your industry).

2. Press Approved Copy, or When Your Words Come Back to Haunt You. The copy on your release is assumed to be vetted and usable for the press. It is likely that one outlet or another will just lift the synopsis, or even the entire release, and reprint it online or in the newspaper. The first time I saw this it was a little weird, but by the very nature of what the document is, the words on the release are fair game for repurposing.

3. SEO Optimization. Having the release available on your website, your publicist’s, publisher’s, etc., gives you more real estate online and can offer more search results. You will notice a search for your book brings up Amazon and other big properties first; your publisher and your own website can appear on the first or near the top of the second page. It gives you more power online when there are more references to you and your work.

4. Standard Practices. More people want to see a release than not because it’s part of the public relations/media relations process. Un addition, your booksellers, event coordinators at higher-end venues, and librarians want to see the meat of what you are selling without having to read the entire book. Having a press release gives you a more serious, professional persona when you are marketing your book. It says you mean business and people should pay attention to you. Don’t sell yourself short.

The other more esoteric reason for the release is that it is an opportunity for you and your publicist to come to an understanding of what your intention is about your book and its relevance. It’s important to be fully aware of how the book will be presented and to settle on the message that you would feel comfortable with if it ran in a newspaper or online.

The structure of a release is based on how much interesting or provocative information you can share without overhyping your message. When you introduce the book, in the opening paragraphs, you will need to identify it using the entire title with the subtitle and in parentheses include the publication date, imprint, format, price, and ISBN, like this:

The Great Book: A Novel by Bobbie Bobs (imprint name, publication date, format, ISBN, price).

The first one or two paragraphs should tell the reader of the release why this is a compelling book and what its relevance is to the audience. You will also want to explain why you wrote the book and how your story personal story is connected to it.

The following paragraphs should be a short synopsis of the plot if you are promoting a novel, and a list of the main facts or talking points if you are working on nonfiction. You can also include a more in-depth section on yourself and your story as it relates to the content if you have a strong personal connection to the material.

Within the release, you will want to mention the book’s title at least three times. In the final paragraph, you need to develop an action statement that will tie up everything you have said so far and will encourage the reader to pick up the book and open it! Before you hit spell check, add your short bio under “About the Author” and the specs of the book (the ISBN, etc.) below that. Finish it off with the traditional “# # #” centered on the bottom, which indicates to the media person that all of the words preceding the symbols are approved for the press. To read some examples of releases, go to my website and look under Campaigns.

What is a pitch and how do you write one?

Pitches should fit the media contact receiving them. The press release is pasted below the pitch so the person can choose to learn more about the book. But not everything will get read. The release is an informational supplement that provides another tool for marketing. If a contact only wants to read three sentences, fine. If more is desired, it’s all there.

I have found that authors are much more comfortable summarizing their books than they are “selling” them. A pitch needs to sell something, plain and simple.

The pitch is not the press release. While a press release needs to have some of the most intriguing information about the book, you, and what you are trying to tell your readers, a pitch is a “harder” sell. The idea is to consider to whom you are writing, and to reach out with just the right story at the right time. And, by the way, the first two or three sentences need to hook your target or it’s all over. It’s kind of like auditioning on Broadway. You have eight bars baby. That’s it, so make them shine!

After you have grabbed the attention of the journalist, blogger, bookseller, or producer, you need to include what I call the “meat” or substance that your work will provide to a viewing audience. If your book has a strong nonfiction hook (your personal story can be the strongest hook, even for a novel), then you will need to explain the “story” that makes it interesting. If it is fic-ion, you will explain another story, except this one will be the essence of the plot or characters of the book. This is similar to what you have included on your press release, but not more than a brief paragraph or two.

The end of the pitch is anything else pertinent to the contact, whether it is an event you are doing in a specific market, or simply your (or your publicist’s) contact information. Here are some sample opening lines of successful pitches for nonfiction and fiction titles.

Memoir/Business

Subject line:

She ran a billion-dollar business and changed fashion

Kym Gold, co-founder of True Religion Brand Jeans, changed the way we view and wear denim. This Malibu native is coming to New York in September to promote her book called Gold Standard: How to Rock the World and Run an Empire, in which she relates the story of her life growing up in California; being one of three triplet girls; marrying Mark Burnett and getting divorced; starting a T-shirt business on Venice beach; and years later, married again, running a billion-dollar company, and raising three kids.

Novel

Subject line:

NJ Family Therapist Dr. Laurie B. Levine pens coming-of-age YA novel

How does an inappropriate student-teacher relationship form, and what are the lasting effects? When Maplewood resident and family therapist Dr. Laurie B. Levine heard that a female Maplewood teacher was arrested for abusive treatment of students, she pulled her young adult novel, on a similar subject, out of the drawer and finished it.

The two biggest mistakes I’ve seen in pitches are that they are too long in length, and not pointed or provocative enough. Clearly you don’t want to create any “fake news” or overhype your pitch, which is just annoying to anyone reading it, but you do need to consider what will make it relevant. The pitch should light the fire and the press release (along with the full media kit—Q&A, bio, talking points) are the fuel that will build the bonfire of interest from media and potential readers.

The two biggest mistakes I’ve seen in pitches are that they are too long in length, and not pointed or provocative enough. Clearly you don’t want to create any “fake news” or overhype your pitch, which is just annoying to anyone reading it, but you do need to consider what will make it relevant. The pitch should light the fire and the press release (along with the full media kit—Q&A, bio, talking points) are the fuel that will build the bonfire of interest from media and potential readers.

If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend Do You Know What a Book Publicist Does? by Claire McKinney.

June 19, 2017

If You’re Successful, Lots of People Ask for Your Help. Who Deserves It?

Early in my writing and publishing career, I was invited to speak to an undergraduate class about research and interview techniques. One of the student questions was, “How do you get important people to respond to an interview request?”

I failed to offer any advice beyond the obvious: Write a good request letter. The professor jumped in, as this was a problem that annoyed her as well. It seemed the students—by the very fact of being students—had difficulty getting their requests taken seriously. How could they overcome that hurdle?

The question stymied me—why wouldn’t someone respond to a polite request? Back then, I responded to every email and request I received when working at a publishing house, as it was flattering to receive any attention at all. Perhaps it helped this was during a different era of email, around 2000 or 2001, prior to social media, when I was still crafting emails the way I did handwritten letters—long, drawn out affairs. I was still eager to check my inbox.

Today, even before I open my email, my blood pressure spikes thinking of all the requests, problems, and complaints I’m likely to find. And I receive at least one or two requests per week from students who are researching a dissertation or class assignment.

“What is the future of publishing?” they ask. Or, “How has the publishing industry has changed over the last 10 years?”

Often, I don’t respond. Recently, though, I did, to a brief and well-written request, and when the follow-up came, it was about 15 very generic industry questions—probably sent to half a dozen other people as well. Answering them thoughtfully was going to consume an entire afternoon. I was immediately sorry I had let down my guard. What was my responsibility to this person?

Last week, I read a post by Steven Pressfield: Clueless Asks. Pressfield is the author of The War of Art, as well as the more recent Turning Pro—some of the best insights into writer psychology. Pressfield defines clueless asks as requests coming from strangers who send him unsolicited work, want to schedule a “pick your brain” lunch meeting, or ask questions they could find the answers to themselves (among other things). He writes:

These are not malicious asks. The writers who send them are nice people, motivated by good intentions. They’re just clueless. They have committed one of two misdemeanors (or both). First, they have demonstrated that they have no respect for my time—and no concept of the value of what they’re asking me for. … The real ask in these cases is “Can I have your reputation?” In other words, “Will you give me, for free, the single most valuable commodity you own, that you’ve worked your entire life to acquire?”

As someone on the receiving end of many clueless asks, what Pressfield says resonates with me deeply. His post is the sort of thing I might have written, and certainly not a week passes when I don’t privately share a clueless ask with my partner and express frustration. But Pressfield may be letting us both off the hook a little too easily.

First, and most obviously, this is a complaint of the successful and privileged few. Airing such a complaint can be a terrible idea, as few are likely to be sympathetic (except other successful people). If you read the comments under Pressfield’s post, you’ll see what I mean.

I’m sure he’s accepted that “clueless asks” are a feature of the successful person’s life. You don’t get the good parts without the more annoying. Yet at some point (it’s irresistible), it seems every successful person (at least those who blog) eventually write a post that can be summed up as: “Please, for the love of God, be smarter about the questions or asks you’re making.”

The thing is, it’s pretty rare that one’s pleas will reach the people who need to hear it or would listen. It reminds me of a similar phenomenon with agents who never stop admonishing: “Read the submission guidelines! Only submit what I actually represent!” It’s a valid admonishment, but probably 99 percent of writers who go to conferences or read publishing guidebooks know that already. The majority of queries that agents receive are from people who will never attend a conference or educate themselves on proper etiquette. But because it’s the thing that annoys agents day in, day out, they can’t help but admonish the people whose ear they do have.

This doesn’t answer the question, though, of what responsibility the successful might have toward others—or what is owed. Here, I likely diverge from Pressfield. What authority, status, and success I have is partly (maybe wholly) the result of those who have granted it to me. If I am a publishing expert, it’s because you say or believe I am. I’m reminded of an Alan Watts lecture, where he says:

You can’t talk about a person walking, unless you start describing the floor. Because when I walk I don’t just dangle my legs in empty space. I move in relationship to a room. So in order to describe what I’m doing when I’m walking I have to describe the room, I have to describe the territory.

So in describing my talking at the moment I can’t describe this just as a thing in itself because I’m talking to you. So what I’m doing at the moment is not completely described unless your being here is described also. … We define each other, we’re all backs and fronts to each other. We and our environment, and all of us and each other are interdependent systems. We know who we are in terms of other people.

What I have was not created solely through my own hard work. My reputation is not something I own; it is something that has been formed and granted over time within a community. And I have a responsibility to that community—to help others and share what I have. It also helps to remember what it was like when no one answered my emails (yes, I’ve made some clueless asks myself). The clueless asks never go away, but perhaps there’s a better way to handle them than to judge or dismiss them entirely.

There’s a saying, attributed to Malcolm S. Forbes: “You can easily judge the character of a man by how he treats those who can do nothing for him.” Assuming for a moment this is true, then in the Internet age, how could one live up to this maxim without considerable sacrifice, given how easy it is for public figures to be exposed—and expected to respond—to the communications of the many? There is no easy answer that I can see, but at least we can reflect on and recognize what choices we make—where we draw the line.

Without question, my contact page pushes against the clueless ask. It states that if it takes me a few minutes to respond to a message, I will; if it really requires a business transaction (a consultation), then I will not.

That said, anyone—including myself—who receives clueless asks already knows the most frequently asked questions. They know the pattern of request. And that makes it straightforward to create standard responses that can be sent in less than a minute, even by an assistant, that offer next steps, resources, and information on how the asker can help themselves. Maybe it’s a small thing, but at least it’s acknowledgment. Yes, I see you. You exist.

This is not to say that I am doing better than Steven Pressfield, or that he is abdicating responsibility in some way. Most authors choose specific and meaningful ways to give back to the community, and answering unsolicited emails can be a thankless, invisible, and time-sucking task. Still, for the community of people I reach, email is the tool of those of very little means, and I feel I’m doing some good through those I do answer.

As far as the student who sent me the 15 generic questions, I did respond. I didn’t respond to every question, and sometimes I simply linked to relevant and publicly available articles I’ve written. I did what I could to meet her halfway. It seemed a good compromise.

June 15, 2017

How to Choose and Set Up a Pen Name

Photo credit: Thomas Rousing Photography via Visual Hunt / CC BY

Today’s guest post is by attorney Helen Sedwick (@HelenSedwick) and is adapted from her newest edition of Self-Publisher’s Legal Handbook.

Choosing a pseudonym can be as daunting as naming a character, especially since the character is you. The simplest pen name would be a variation of your own name, such as a middle name, nickname, or initials. Many authors change only their last name so they don’t have to remember what first name to use at conferences. Once you decide on a list of possibilities, do the following.

1. Research the name.

Search the internet and bookselling sites. Avoid any name already used by a writer, since that is likely to confuse readers. Do not use the name of anyone famous. If you write a book under the pen name Taylor Swift or Derek Jeter, you may be accused of trying to pass yourself off as the celebrity.

I also suggest a trademark search through the U.S. Trademark Office. If you use the name of registered trademarks, you risk getting a cease-and-desist letter.

Try to avoid using the name of a real person. If you happen to use the name of a real person, you are not committing identity theft. Identity theft involves intentionally acting to impersonate someone for financial gain. But if your writing affects the real person’s life, consider changing your pen name.

2. Buy available domain names.

You will want to buy a website domain for your pen name.

3. Claim the name.

File a Fictitious Business Name Statement (FBN Statement) if you will be getting payments made out to your pen name. In some jurisdictions, you may have to add the word Books or Publications after your pen name because the local jurisdiction won’t accept a Fictitious Business Name that looks like the name of a real person.

4. Use the name.

Place the pen name on your cover and your copyright notice: © 2017 [your pen name]. Some authors put the copyright notice in both their pen name and real name, but it is not necessary.

5. Be open with your publisher.

Usually, you will not be able to hide your real name from your publisher since contracts are signed in your real name. The exception is when you form a corporation, LLC, or other entity, but even then, most publishers want to know their authors.

6. Register your copyright.

You may register the copyright of your work under your pseudonym, your real name, or both. There are downsides to registering the copyright under a pseudonym only. First, it may be difficult to prove ownership of the work at a later date. Second, the life of the copyright will be shorter: 95 years from the year of first publication or 120 years from its creation, instead of 70 years after your death.

I recommend that authors register their pseudonymous works under both their real names and pen names. This creates a permanent record of ownership, and few readers are going to research copyright records and find out the author’s real name.

There is no way to “claim” a pen name as exclusively yours. You may go through the process of filing an FBN Statement, but that gives you the right to use that name, not the right to stop others from using the same name (unless they happen to be doing business in the same county as you). If you become very famous under your pen name, then you might have other options. If that happens, you should engage a lawyer to help you.

What Not to Do

Don’t go overboard in creating a fake identity. Never claim credentials you don’t have. Using made-up credentials, especially to market an advice book, would be a misleading business practice.

Don’t use a pen name to avoid a pre-existing contract. If you have granted a traditional publisher first-refusal rights or have signed a confidentiality agreement as part of a legal settlement or employment agreement, a pen name won’t change anything. You are still breaching your obligations.

Don’t expect a pen name to protect you completely from defamation claims. Most likely, you will be found out either through legal process or technology.

Licensed Professionals Using Pen Names

Using a pen name for a book containing professional information may not be permitted by the rules of your license. For example, the American Bar Association and the California State Bar would consider my book Self-Publisher’s Legal Handbook a “client communication” and “advertisement.” Therefore I must disclose my real name according to ethical rules. If I were writing a novel, I would have more freedom to use a pen name because readers are not relying on my legal credentials.

Secrecy and Pen Names

You should consider how secret you want to be about your true identity. Maintaining secrecy is difficult. The higher the level of secrecy, the more complicated the process. Plus, you need to keep track of which identity to use in what context.

Most authors choose to be open about their pen names. At book signings, they use their pen names, but at writers’ conferences they use their real names with a reference to their pen names. For example, Dean Koontz lists his various pen names on his website. Some authors are more discreet. They try to maintain their privacy, but not to the point of lying. They don’t put photos on their books and blogs, do not link their websites, and limit public appearances. For a bio, they use their own life story, but told in generic terms. David Savage (a pen name) did that with his bio for his book How the Devil Became President.

Other authors put up roadblocks. They set up corporations and trusts to hold the copyrights and contracts. This is the most expensive alternative and may require an attorney. Even then, someone will know who is behind the corporation, and word may leak out. In this internet age, secrets are almost impossible to keep. Remember what happened to J. K. Rowling? She tried to keep quiet about her pen name Robert Galbraith, but it was leaked by, of all people, her lawyers.

Other authors put up roadblocks. They set up corporations and trusts to hold the copyrights and contracts. This is the most expensive alternative and may require an attorney. Even then, someone will know who is behind the corporation, and word may leak out. In this internet age, secrets are almost impossible to keep. Remember what happened to J. K. Rowling? She tried to keep quiet about her pen name Robert Galbraith, but it was leaked by, of all people, her lawyers.

If you found this post useful, I highly recommend Helen Sedwick’s Self Publisher’s Legal Handbook.

June 12, 2017

How to Immediately Improve Your Query Letter’s Effectiveness

In my many years of critiquing queries, I see the same weaknesses again and again. Here are the biggest problems that afflict novel queries and how you can fix them.

Remove anything that sounds like a book report.

This is by far the biggest sin of most query letters. It’s where you try to explain in detail what happens in your book, thinking that the more intriguing or juicy description you share, the more interested the agent or editor will be.

No. In fact, you want to pull back—way back. All you need is something very simple (yet difficult): the story premise. The premise consists of the protagonist(s) and the challenge they face. We need a fairly equal balance of character and plot here—enough to connect with the character and enough to be interested in the problem that will drive the story from beginning to end. You should avoid anything that is an accounting of the plot twists and turns. (If agents want to know that, they will turn to the novel synopsis.)

Here’s an example where there’s waaaay too much detail. (I’m using the TV series “The Vikings” as the story I’m pitching, as if it were a novel.)

In eighth century Scandinavia, a young Ragnar Lothbrok and his brother Rollo have just won a major battle together against Baltic tribesman, but Ragnar feels dissatisfied with his life. Possessing a heretofore-unknown navigational device obtained from a foreigner, he tries to convince the Earl Haraldson that instead of raiding again in the east as they’ve done for generations, they should try voyaging to the mythical lands to the west to find riches. Ragnar and Rollo argue over the which of them will lead this voyage, and they eventually agree to sail as equals and form a crew, after having their shipbuilding comrade Floki design a new, fast-moving boat. After many travails at sea including a devastating storm which almost sinks their craft, they arrive in England and plunder a monastery with their crew and take slaves back home to Scandinavia, including a young monk named Athelstan. Earl Haraldson feels threatened by the success of the raid, and Ragnar is put in his place, but not for long. A long series of raids to England begins, and Ragnar finds that as he gains confidence and stature, his brother Rollo feels left behind and jealous, and ultimately betrays him. Ragnar is torn between being loyal to family and punishing his brother.

The paragraph above is basically a plot synopsis, which we don’t want in a query. It tends to be mind numbing and sometimes hard to follow. Agents and editors want to feel excited to read the manuscript, and not linger over the query any longer than necessary. Here’s an example of how to pitch the premise and not the plot:

Young Ragnar Lothbrok, the very first Viking to sail west from Scandinavia, sets off a chain of events that will forever change England and the heart of Europe.

Ragnar is a warrior and a farmer, headstrong, who is frustrated by his kingdom’s tired tradition of raiding to the east. He has undertaken a secret project—better designed boats and navigation devices—to sail to the unknown west. Seen as an arrogant fool by his kingdom’s earl, he manages to convince enough people, including his brother, Rollo, to go with him on the unpredictable journey. His daring adventure will turn the Viking world on its head—and also turn his family against him.

Notice how this gives us a sense of what Ragnar is like and his motivations for doing what he does. We don’t need to know the plot specifics beyond what sets the story in motion and what will keep us turning the pages. Notice the length: not even 100 words.

Leave out your motivations and reasons for writing the book.

Bottom line: your motivations rarely matter to agents/editors making a decision on whether to read your manuscript. Leave that discussion for your interview with Terry Gross or others who are curious about your creative process.

However, it’s totally fine to reference research you conducted or perhaps professional experience you have that may have helped you produce a more credible or authentic story.

Use a light touch when discussing your novel’s themes or “lessons.”

This is kind of like the cousin to your motivations for writing your book. You may be very concerned about demonstrating a certain value or judgment or lesson through the characters or story line. You might summarize this in a sentence or so near the end of the query, e.g., “Through Olivia’s journey, we learn what it means to love others, and through them, love ourselves.”

It’s not a problem if you mention such a thing briefly (usually after delivering the story premise), but if you have a full paragraph dedicated to explaining the novel’s overarching theme, it may make your work sound pedantic or too self-serious.

Don’t talk about how your family and friends love your work—and be careful of mentioning anyone’s praise.

Frankly, no one’s opinion matters except that of the agent or editor who is evaluating your work. They definitely don’t care about how much your writing group or beta readers have enjoyed the book, nor do they care about your students, friends, family members, or anyone else for that matter.

Sometimes writers will be tempted to add the praise of mentors, authors, or even professional editors who’ve read and helped with the work. Think twice before you do. Whatever people you mention would first have to be known and meaningful to the agent/editor being queried, and second, it raises the question of why these people who are praising your work haven’t given you a formal referral or written on your behalf to an agent/editor. (It’s rare for someone to do so, but it’s usually the only kind of endorsement that will really change how much time an agent or editor puts into considering your work.)

Keep total query length to around 300 words.

Your query letter mostly consists of the story premise. You’ll also mention the basic facts of the work—title, word count, genre—and probably include a line or two about yourself. (Read my guide to novel queries for more on query elements.) All together, your query length should be around 300 words, maybe less. If your query runs an entire single-spaced page, you’ve likely said too much.

The query letter is about seduction; you want to leave something to the imagination, and you want to leave the agent/editor wanting more. Almost no one will complain that your query is too short.

June 8, 2017

When You Actually Should Dig Out Those Old Stories From the Dusty Drawer

Photo credit: rusty_cage via VisualHunt.com / CC BY

My partner, Mark, is a packrat. While he has tried hard to “purge” his various collections in between moves, we still have closets, and an outbuilding, filled with boxes of ephemera from his youth. Some of it includes things he’s written, things he would probably say he’s embarrassed by. Yet still he holds on.

This gives me plenty of opportunity to tease (or taunt) him about it. Why be so sentimental?

After reading “Looking Back,” by Andrew Porter, perhaps I’ll become more sympathetic. He writes:

There are any number of reasons for why stories get orphaned and forgotten, why they get sent to the darkest corners of our hard drives. Sometimes they may belong there, but other times I think they remain there simply because we’ve chosen to forget them, or worse, because we’ve given up on them. … [I tell students] if there’s something at the heart of the story that still interests them, that keeps pulling them back, that still haunts them years later, then that’s probably a sign that there’s something worth struggling for there, that somewhere, in the midst of all that mess, they might even find some of their very best work.

Also this month from Glimmer Train:

A 100% Rejection Rate by Weike Wang

Some Lessons Learned by Bipin Aurora

On Gathering Material by Stefanie Freele

Laying Fiction Over History by Peter Ho Davies

June 7, 2017

The Perfect Cover Letter: Advice From a Lit Mag Editor

Today’s guest post is from Elise Holland, co-founder and editor of 2 Elizabeths, a short fiction and poetry publication.

When submitting your short-form literature to a magazine or journal, your cover letter is often the first piece of writing an editor sees. It serves as an introduction to your thoughtfully crafted art. As such, it is significant, but it shouldn’t be intimidating or even take much time to write.

As editor at 2 Elizabeths, I see a variety of cover letters every day; some are excellent, and others could stand to be improved. There are a few key pieces of information to include, while keeping them short and sweet. In fact, a cover letter should only be a couple of paragraphs long, and no more than roughly 100-150 words.

A little research goes a long way

Seek out the editor’s name, and address the letter to him/her, as opposed to using a generic greeting. Typically, you can find this information either on the magazine or journal’s website, or in the submission guidelines.

Read the submission guidelines thoroughly. Many publications will state in their guidelines the exact details that need to be included in a cover letter. With some variation, a general rule of thumb is to include the following:

Editor’s name (if you can locate it)

Word count

Title

Genre/category

Brief description of your piece

If you have been published previously, state where

Whether your piece is a simultaneous submission (definition below)

Your name

Terms to Know

The term simultaneous submission means that you will be sending the same piece to several literary magazines or journals at the same time. Most publications accept simultaneous submissions, but some do not. If a publication does not accept them, this will be stated in their guidelines.

Should your work be selected for publication by one magazine, it is important to notify other publications where you have submitted that piece. This courtesy will prevent complications, and will keep you in good graces with various editors, should you wish to submit to them again in the future.

The term multiple submission means that you are submitting multiple pieces to the same literary magazine or journal.

Cover Letter That Needs Work

Dear Editor,

Here is a collection of poems I wrote that I’d like you to consider. I have not yet been published elsewhere. Please let me know what you think.

Bio: John Doe is an Insurance Agent by day and a writer by night, living in Ten Buck Two. He is the author of a personal blog, LivingWith20Cats.com.

Best,

John Doe

What Went Wrong?

John Doe didn’t research the editor’s name. A personal greeting is always better than a simple “Dear Editor.” Additionally, John failed to include the word count, title and a brief description of his work.

There is no need to state that John has not yet been published elsewhere. He should simply leave that piece of information out. (Many publications, 2 Elizabeths included, will still welcome your submissions warmly if you are unpublished.)

John included a statement asking the editor to let him know what he/she thinks about his work. Due to time constraints, it is rare that an editor sends feedback unless work is going to be accepted.

Unless otherwise specified by the magazine or journal to which you are submitting, you do not need to include biographical information in your cover letter. Typically, that information is either requested upfront but in a separate document from the cover letter, or is not requested until a piece has been selected for publishing.

Cover Letter Ready to Be Sent

Dear Elise,

Please consider this 1,457-word short fiction piece, “Summer.” I recently participated in the 2 Elizabeths Open Mic Night, and am an avid reader of the fiction and poetry that you publish.

“Summer” is a fictitious tale inspired by the impact of a whirlwind, yet meaningful, romance I experienced last year. In this story, I gently explore the life lessons associated with young love, with a touch of humor.

This is a simultaneous submission, and I will notify you if the piece is accepted elsewhere.

Thank you for your consideration.

Kindest Regards,

John Doe

What Went Right?

In this letter, John includes all pertinent information, while keeping his letter clear and concise. In his second sentence, John also briefly states how he is familiar with the magazine. While doing this isn’t required, if done tastefully, it can be a nice touch! Another example might be: “I read and enjoyed your spring issue, and believe that my work is a good fit for your magazine.”

I hope these sample letters help you as you send your short works to magazines and journals for consideration. While you’re at it, I hope you will check out 2 Elizabeths! We would love to read your work.

June 6, 2017

Why Your Memoir Won’t Sell

Note from Jane: This week, I’m kicking off a 5-week online course on how to write a nonfiction book proposal. If you’re a memoirist preparing to pitch your work this year, it may benefit you, and it’s not too late to register.

Of all the projects I’ve heard pitched over the years, memoir is the category with the most intractable, hard-to-solve problems. Partly this is a function of what memoir is: something that’s very personal. People have a hard time achieving any distance between the meaning and importance of their life’s events and the commercial market that might exist for it.

What I’m about to write may come off as cold and insensitive. File it under “tough love for writers.” It’s not that your life is unimportant or without value. Quite the contrary. Everyone has a meaningful story to tell, but not everyone’s story (or writing) is going to deserve a commercial publishing deal.

Here are the most common problems I encounter in memoir pitches and manuscripts.

The memoir is the first piece of writing you’ve ever attempted.

It’s often said that a writer’s first manuscript never gets published; it’s the third, fourth, fifth (or later) manuscript that gains acceptance by a publisher. While this principle is common in relation to fiction writing, I think it applies to any type of storytelling. If your memoir is the first thing you’ve written and finished, it’s unlikely you knocked it out of the park on your first try. Of course, anything is possible, but you’re relying on being an outlier.

Your memoir is primarily pain focused, or an act of catharsis.

This problem often goes hand in hand with the first. Someone has experienced something traumatic, and as part of their therapy or recovery, they write about the experience. Before long, they have a book-length work, and friends and family say (as a form of well-meaning support), “You should find a publisher.”

No, you probably shouldn’t. If your writing was:

undertaken as a way for you to deal with a painful experience

if that painful experience is in the recent past (within the last few years), and/or

if you have no other writing experience or ambition …

… then publishing a memoir isn’t the best next step for you. It’s great that you’ve used writing to aid in recovery, but it doesn’t mean you have a book that’s appropriate for the commercial market. (Unless you’re Hillary Clinton and you lost the 2016 presidential election.)

Your memoir consists of diary or journal entries, letters, or other ephemera from the past.

Don’t do it. One of the fastest ways to get a rejection is to pitch your book as a collection of entries from a diary or journal you kept or a family member kept, or letters sent and received.

Okay, maybe if you’re a celebrity, notorious for some reason, or otherwise in the public eye, perhaps these materials will hold interest to a general readership. But for the most part, a collection of journal entries is going to elicit a yawn from those in publishing.

Use diaries, journals, and other personal written materials as the basis of research to write a proper, narrative-driven story. But don’t use them as the story itself, or use them very sparingly within a larger narrative.

(Yes, I know Sedaris is publishing his diaries. You’re not Sedaris.)

Your memoir is really an autobiography.

This happens about half the time I read a memoir chapter outline or synopsis: it begins in childhood and ends in the present day. In other words, it looks more like an autobiography.

Most memoirs should be limited to telling a story about a particular period in time. A distinctive lens or angle is applied—which means many chapters (and characters) of your life will not enter into the picture. While many phases of your life may be referenced, or there might be flashbacks or flash-forwards, the narrative ought to have a clear focus, or a beginning-middle-end, that isn’t defined by the day you were born and the day you started to write your life story.

Sometimes you can get away with something very broad ranging indeed, but it requires a skilled storyteller, who knows how to weave together scenes to create a cohesive narrative.

You’ve written a series of vignettes.

A vignette is a story that stands alone and is little more than an anecdote about your life. Some memoirs consist of nothing but back-to-back vignettes. They might be beautiful and touching vignettes, but the manuscript lacks a narrative arc. There’s no real story; there’s no question that keeps us turning pages.

Some authors can get away with publishing essay collections or something that looks like a collection of vignettes. Again, people love to reference David Sedaris, as well as Erma Bombeck, as a way to say, “But look how popular they are!” But you are not them, and you won’t get the same latitude if you’re a relative unknown.

You’ve written the memoir of someone else.

You have a family member and they have an amazing story to tell. But they’re not a writer, or they don’t care to write it (or they’re dead). But you’re motivated to do something. So you embark on writing the memoir (or sometimes biography) of their lives.

This type of project is unlikely to go any further than your computer hard drive unless you self-publish it. There is great value in writing and self-publishing such a story for the family legacy, but unless you have a track record of writing and publishing amazing stories about (or for) other people, prepare to be disappointed in the reaction of editors and agents.

Your story is like a million others (and the writing just isn’t special enough).

This is the hardest thing to tell a writer: “Sorry, but your story of addiction or cancer survival or loss of a child just doesn’t seem that special.” In other words, your story sounds like everyone else’s story. It’s not written in a way that makes it stand out, or it could be written poorly. The only antidote to this problem is to either become a better writer, or to find a more interesting story to tell.

For more tough love on memoir, I highly recommend this agent roundtable published in Writer’s Digest in 2010. It’s still relevant today.

June 5, 2017

Fan-Friendly Marketing and Kindle Worlds Licensing: Q&A with Aleatha Romig

Today’s Q&A with novelist Aleatha Romig is by journalist and romance writer Cathy Shouse (@cathyshouse).

Aleatha Romig (@aleatharomig) is a New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and USA Today bestselling author best known for the Consequences and Infidelity series, dark psychological thrillers that are also considered dark romance. Infidelity was named by Redbook magazine as one of 11 sexy books to read after Fifty Shades of Grey.

Primarily an indie published author, Romig participates in Kindle Worlds, which allows other authors to write about the characters in her work. She also has fans all over the globe, and has traveled to see many of them at author events. Recently, she took the time to answer some questions via email about the development and marketing of her work, particularly Kindle Worlds.

Your debut novel, Consequences, was indie published and that seven-book series is described as dark psychological thrillers/dark romance. In May, you introduced “the lighter side of Aleatha” with Plus One, a romantic comedy. Why are you switching from what generated your success?

I don’t think of it as switching genres. I think of it as adding a new genre to my repertoire. I have released dark romance; romantic suspense saga; sexy, smart thrillers; romantic thrillers; and now I’m adding romantic comedy to the mix.

I don’t think of it as switching genres. I think of it as adding a new genre to my repertoire. I have released dark romance; romantic suspense saga; sexy, smart thrillers; romantic thrillers; and now I’m adding romantic comedy to the mix.

The last thing I want to be is formulaic. To be honest, it is why I didn’t like romances growing up. They were too predictable.

That said, after my hugely successful Infidelity series (which is not about cheating—see, I’m keeping you guessing!), I was exhausted. I’d written five full-length books of more than 100,000 words each in eighteen months. I was mentally drained.

Before I was an author, as a reader, I loved dark thrillers. I could read two or three and then I needed a break. Janet Evanovich was my break. I would laugh out loud with Stephanie Plum. It occurred to me that the break I needed after Infidelity could be found in writing a romantic comedy. Yes, it’s a big leap. To be honest, I wasn’t sure I could do it. So I did it on the sly.

In 2016 with the help of a friend who is also another New York Times author, we created a pseudonym. Under this new name, we published seven titles. We each wrote our own books, but used the same name. The titles we released were fun, smutty novellas. It was as Jade Sinner that I learned I could do comedy, that I enjoyed it.

In 2016 with the help of a friend who is also another New York Times author, we created a pseudonym. Under this new name, we published seven titles. We each wrote our own books, but used the same name. The titles we released were fun, smutty novellas. It was as Jade Sinner that I learned I could do comedy, that I enjoyed it.

The beginning of this year, we decided to discontinue Jade. It wasn’t that she wasn’t successful. It was that we were both too busy with our own names and promotion to give her the attention she deserved. We each retained the rights to the titles we individually wrote. That was how I took a short, 12,000-word novella, and added the meat and spice to create Plus One.

I don’t intend to leave dark behind. As a matter of fact, this summer I have a fun surprise coming. But I’d love to do more rom-com. I enjoy embracing all sides of Aleatha, the dark and the light, the thriller and the romance.

You’ve traveled extensively to participate in multi-author events where I’ve seen long lines waiting, and you ran out of books. You also interact online and in person, not only with readers but with writer friends at meetings and informal gatherings. Even new writer friends have gotten your help with uploading their debut novels, and you have shared all you have learned. Why do you make the effort and doesn’t it take away from your writing time?

My husband, Mr. Jeff, and I have traveled to over eighty cities in the US and abroad over the last three and a half years. We’re taking most of 2017 off from traveling for author events, though we will be in California in June.

I believe that interaction is key to everything. As authors we are typically introverts and I’m no different. A day-long signing is exhilarating and exhausting. But it’s the interaction that creates a bond between authors and between authors and their readers. I have an amazing fan base that constantly shocks me. I mean, I never expected more than my mom and a few of her friends to read my books. Nevertheless, interacting with those fans, whether at an event or on social media, helps to create and glue that connection. It’s fun to finally meet someone after interacting with them online.

My online presence was born after Jane Friedman came to our Indiana RWA group in 2011, the year I published Consequences. At that point I wasn’t on social media. Today I have over 34,000 followers on Facebook, 14,000 on Twitter, and 11,000 on Instagram. That doesn’t include Goodreads, Pinterest, and my 5,000 friends on Facebook.

From the very beginning of self-publishing in 2011 I’ve been blown away by the willingness of other self-published authors to help one another. We essentially created our own support systems. Early on, we came to the conclusion that seemed to be missed in years past: No one reads one book or one author. If a reader likes my books and I like another author’s books, my readers will probably like them too.

From helping with story ideas, to formatting, to marketing, we have worked together to change the publishing industry forever. The authors who started this journey with me in the beginning have become some of my closest friends and allies. Author events are like class reunions when we can all get together. We have worked to help those we can along the way. It all evens out in the end. I’d much rather help someone succeed then stand by and watch their dreams fade. To the authors who helped me and continue to help me, I’m eternally grateful!

What advice would you give someone about writing that first book and wanting it to be a series?

Writing the first book in a series is tricky. It needs to catch the readers’ attention, give them a sense of fulfillment, and leave them wanting more. I realize those last two sound opposing, but they’re not.

My series are not a group of standalone stories, where each book has its own complete arc, or where the next book in the series offers another complete story of two side characters who are now the primary characters. I’ve read those series and I enjoy them. One of my favorites would have to be A.L. Jackson’s Bleeding Heart series.

My series, Consequences and Infidelity, are five books following the same couple with cliffhangers at the end of each book. Some would call that a serial. I don’t disagree. What I find fault with is the idea that a serial is one book cut in five. My Infidelity series is five complete books with one overall story arc following the same characters. Within each book, issues are resolved and new issues arise until we reach the epic dramatic conclusion.

Expecting a reader to move through five full-length books means I need to keep their interest. I need to weave a web so involved and intricate that they MUST continue reading. There is a lot of pressure to keep the story fresh. If book three is not fulfilling, the readers won’t go to book four. If one through four are amazing, but five leaves them unsatisfied, the entire series is a failure. Each book must lift the bar higher so the reader stays engaged.

Another factor with writing a series like mine is to produce books quickly. I wrote each book, then edited, formatted, and produced everything within three to four months.

While I’m currently releasing my second standalone novel, I am known for my series. My readers enjoy the depth that only 500,000 words can provide. They understand that to embark on a journey with me will be epic and unforgettable. Even after fulfilling the five-book commitment with Infidelity, I daily receive requests for stories and novellas on other characters. I’m currently writing Respect, the standalone story of Oren Demetri. As the Infidelity series progressed, it became clear that Oren had more story to tell.

Your Infidelity series released in Kindle Worlds in March of 2017 with nine titles written by other authors and set in the book world you created. How did you decide to participate in Kindle Worlds and how does it work?

I was approached by Amazon Publishing during the summer of 2016 and asked if I would be interested in releasing an Infidelity World into Kindle Worlds. The platform has been around since 2013. It’s essentially a platform to open licensed worlds to fan fiction.

As an author, licensing my world to Kindle Worlds allows not only the authors I invited for the initial launch but anyone to write in my world. Each world has a bible, written by the licensed author. My bible has certain restrictions. For example, authors may not write beyond my time line. In other words, my series ended where I wanted it to end. Another author can’t come in, break up my couple or kill off characters that lived to the conclusion.

I debated the decision to agree to an Infidelity World, but decided that it was a way to keep my world alive. It is also an excellent opportunity to encourage and help other authors. My launch included New York Times bestselling author Pam Godwin. Her inclusion into my world was an honor to me. However, many authors who write in Kindle Worlds do not have the fan base of Pam. Kindle Worlds gives these authors exposure. For the Infidelity World launch, my readers and Pam’s readers were introduced to authors they were otherwise unfamiliar with. This has been a win-win for everyone.

Kindle Worlds has set pricing based on word count. The authors receive 35% of all royalties from their own story, and I receive 35% of all royalties on all books published in my world. We all benefit.

How hands-on were you with the Kindle Worlds launch and how will that work going forward? Had you read the books before they released?

I was very hands-on with the first launch of Infidelity World. All of the authors involved were approached by me. They’re not only authors I respect, but my friends. I am invested in their success. I read all nine titles prior to their release, but that was not a deciding factor in any of their content. That was up to them as long as they abided by the rules of my Infidelity World bible.

Another criteria from Kindle Worlds is that my world—i.e., setting, companies, or characters—must be involved in some way. In most of the worlds, at least one of my characters makes a cameo appearance. In some, my secondary or even tertiary characters are given the opportunity to star in their own story. A great example is Suspicion by Donya Lynne. This book is completely focused on a character that enters and exits the Infidelity series in the first chapter of book one, Betrayal, and is never seen again.

Going forward, anyone can write in my world. I will probably not be as hands on, as I have my own production schedule. I will definitely help to promote launches. I have currently hired a world coordinator. If anyone is interested in writing in my world or any other, here is a link.

How do you feel about how the launch went and what was the response?

I think the launch went amazingly well. We had all nine Infidelity World stories in the top 25 of Kindle Worlds. It is a testament to the hard work of the authors in the launch. They all worked tirelessly at creating amazing stories as well as promoting not only their own story, but the entire launch. I worked with them, as did my PR company, and we brought the consultant on near the end. We created a Facebook group for reader/author interaction.

What are you currently doing as far as marketing and how detailed are your marketing plans into the future—or is that something that evolves as the market changes?

I employ Inkslinger as my PR company. The company and especially my representative, Danielle, have been a big part of my marketing plans. We talk about release dates and strategies. My financial advisor works primarily with authors and is incredibly helpful with all things including pricing and marketing.

Currently, Facebook advertising is one of my main focuses. I’m of the belief that you must spend money to make money. The biggest issue in today’s market is visibility. That is the same thing Jane Friedman said years ago when she visited IRWA. The problem today is that getting visibility is more and more difficult.

To be seen, you need to spend money. I run continuous Facebook ads on all my series. Both my Consequences and Infidelity series have their first book free. I am constantly telling the world that the first book free is my “drug deal” to readers. I hope if you read book one, you’ll want more.

Around a release, I up my advertising. Again, it is all about visibility and awareness. I’ve been trying to increase my visibility on Twitter also. I run BookBub ads and features whenever I can. Start small, like a $5 a day ad. If it works, do more of it. If it doesn’t, try something else. But keep trying.

In 2016, your two-book series from Thomas and Mercer, Amazon Publishing’s Mystery/Thriller imprint, released with Into the Light. We’ve been told that the greatest advantage to indie publishing is having total control of the process. Why did you take a traditional contract and were you surprised by some advantages/disadvantages?

I have grown very used to being in complete control of all aspects of my self-published work. Over the years, I have surrounded myself with amazing people: a great editor, whom I adore. Betas, whom I trust. Formatter, who does amazing work. Photographers, cover designers, promotion people, financial people, an agent, etc. I pay a good amount of money for these professional services because this is a profession. Just because someone can do something doesn’t mean they should.

I have grown very used to being in complete control of all aspects of my self-published work. Over the years, I have surrounded myself with amazing people: a great editor, whom I adore. Betas, whom I trust. Formatter, who does amazing work. Photographers, cover designers, promotion people, financial people, an agent, etc. I pay a good amount of money for these professional services because this is a profession. Just because someone can do something doesn’t mean they should.

My traditional experience was completely different. I had one role: the author. Thomas and Mercer was in charge of everything else. My job was to write. I did have a say in things like the cover; however, everything was done on their schedule. The experience was educational. My manuscripts went through four different editors. Personally, I use betas and then do three rounds with my one editor. I found the developmental editor with T&M especially educational. We didn’t see eye to eye on all matters, but the end result is something we can both be proud of. At the end of the day, it is my name on the cover and I wasn’t afraid to stand up for my story.

I’m glad I am hybrid. I would be interested in another shot at traditional publishing, especially with a future thriller. I feel that a traditional market can perhaps do a better job of helping me expand my readership, especially in the area of mystery/thriller readers.

May 31, 2017

5 Research Steps Before You Write Your Book Proposal

Photo credit: The City of Toronto via Visualhunt.com / CC BY

Note from Jane: I’m offering an interactive course on nonfiction book proposals starting June 5. My expertise on this topic comes from more than a decade of acquisitions experience at a traditional publisher, where I reviewed thousands of proposals.

Writing a nonfiction book proposal—a good one—requires not only sharp clarity about your idea, but also how that idea, in book form, is relevant and unique in today’s market. You’ll have a much easier time writing your proposal if you take time to conduct market research beforehand.

Step 1. Explore and understand competing titles.

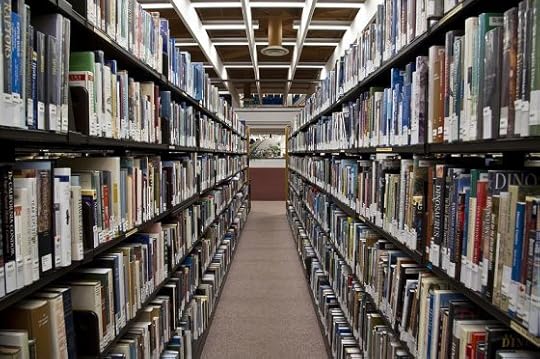

Searching for competing titles—the books that currently exist on your topic and serve the same audience—is one of the easiest ways to begin your research process. Visit the bookstores in your area, and the library, too. Go to the shelf where you would expect your book to be placed. What’s there? Study the books closely and take notes. After you finish combing the bookstores and libraries, check specialty retailers that might carry books on your topic (e.g., Michaels for arts and crafts books). And of course be sure to look at Amazon.

Here’s a worksheet to guide your research of competing titles.

Step 2. Research the digital media landscape.

It would be a mistake to think your competition is limited to print books. Today, your greatest competition may be a website, online community, or well-known blogger. Do a thorough Google search for digital content and online experts serving the same audience as you. Is it easy to get needed and authoritative information? Is it free or behind a pay wall?

Don’t stop at Google. Also search YouTube, app stores, iTunes podcasts, and online communities relevant to your topic. Look for online education opportunities, if relevant. Understand how your audience might be fulfilling its needs for information from online and multimedia sources—and also from magazines, newsletters, databases, and events/conferences.

This information may or may not end up in your proposal, but the upside is this: you’re developing an amazing map and resource of how to market your book when it’s published.

Step 3. Study the authors and influencers you’ve found.

As you go through Steps 1 and 2, you’ll uncover authors, experts, and influencers on your topic. Just as you studied the books and media, dig deep into the platform and reach of these people. How do you fit among them? How will you set yourself apart? Are there hints about how you need to develop your own platform to be competitive in the eyes of a publisher?

Here’s a worksheet to help you take notes on authors and influencers.

Step 4. Pinpoint your primary audience.

By this point, you’ll have considerable information about the print and online landscape related to your topic. You will probably have some notes about the type of audience or demographic being served. (If not, go back and look for clues as to who the books or media appear to be targeting.)

It’s a big red flag to any agent or editor to say that your book is for “everyone.” Maybe it could interest “everyone,” but there’s a specific audience that will be the most likely to buy your book. Who are those people, and how/where can you reach them? Again, Steps 1–3 have probably given you some pretty good hints. If not, try asking the following:

What social media outlets seem to be most important, active, or relevant for your target audience? Where does your audience gather online? What are their behaviors or attributes in those gathering places?

What else does your audience read? What do they watch? Who do they listen to in the media?

Are there any trend articles, statistics or research about your readership that might be helpful? Try running a keyword search through Google, then clicking on the “News” tab to find features or trend reports on your topic. (E.g., if you search for “millennial parents,” you’ll find a boatload of trend pieces and advice on marketing to that demographic.)

The better you know your target reader (or primary market), the better you’ll able to build a proposal that speaks to why anyone cares about what you’re writing. Furthermore, an intimate understanding of your audience often leads to a better book.

Step 5. Analyze how you reach readers.

This is where you look at your platform and measure how well you reach your target readership, through the following:

Your website/blog

Email newsletter

Social media

Speaking and teaching

Professional memberships or affiliations

Partnerships or special connections, especially those that might influence media coverage or buzz

Any other tools you have!

Here’s a platform worksheet to help you cover the most important bases.

This is a good time to refer back to Step 3, and review the authors and influencers you’ll be competing and/or collaborating with. You want to look like you measure up well but also have something fresh or different to offer.

Your platform directly informs the marketing and promotion plan that’s included in your proposal. The best marketing campaigns begin with what you have in place today, not what you hope to happen (e.g., Oprah calls). Also, being thorough in describing your platform (if only for yourself) helps you more effectively develop a marketing plan before your publication day, and collaborate with your publisher on marketing and publicity.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers