Roy B. Blizzard's Blog, page 3

March 19, 2024

Religious Groupthink

Religious Groupthink

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people, where the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. By prioritizing consensus above all else, group members often minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative viewpoints. The term is closely associated with the work of social psychologist Irving Janis, who provided the definitive analysis of this group decision-making error.

Origin of Groupthink

The concept of Groupthink was first introduced by Irving Janis in the 1970s. Janis, a research psychologist from Yale University, was intrigued by how a group's dynamics could influence the decision-making process, often leading to poor outcomes. He identified Groupthink as a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, and the members' striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action. Janis’ groundbreaking work shed light on how Groupthink could lead to catastrophic decisions, as he meticulously analyzed historical instances where Groupthink played a significant role in government decisions, especially in the context of policy blunders and military fiascos.

Groupthink in Religious Contexts

In religious denominations and churches, Groupthink manifests when the cohesive force of the community or the authoritative weight of its leaders stifles individual critical inquiry, leading to a standardized, often uncritical interpretation of biblical texts. The fear of dissent, desire for acceptance, or reverence for tradition can overshadow personal insights, questions, or revelations, resulting in a collective agreement that may not necessarily reflect the text's complexity or intended message.

Historical Examples of Groupthink

Several historical events exemplify Groupthink, showcasing its impact on decision-making:

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (1961): This failed attempt by the US to overthrow the Cuban government is often cited as a prime example of Groupthink. The Kennedy administration's planners were overly confident and did not sufficiently question their assumptions or consider alternative perspectives.

The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster (1986): Engineers and officials at NASA succumbed to Groupthink, ignoring warnings about the O-ring seals' failure in cold temperatures. The decision to proceed with the launch resulted in a tragedy watched by millions.

The Pearl Harbor Attack (1941): Military officials dismissed indications of an imminent Japanese attack due to overconfidence and stereotypes that underestimated Japanese capabilities, illustrating Groupthink’s effect on critical military decisions.

Historical Examples in Religious Settings

Throughout history, there have been instances where Groupthink in religious communities led to significant consequences:

The Crusades: Misinterpretations of biblical texts, compounded by Groupthink, contributed to the zealous and militaristic movements that led to centuries of conflict.

The Witch Trials: Groupthink contributed to mass hysteria and the uncritical acceptance of theologically flawed justifications for the persecution and execution of supposed witches.

Modern Sectarianism: In contemporary settings, Groupthink can lead to extreme sectarianism, where rigid group norms dictate an unchallengeable interpretation of the Bible, often resulting in division and conflict.

Antecedents to Groupthink

Groupthink typically occurs in the context of several antecedent conditions:

High Cohesiveness: When group members form a strong bond, they may prioritize consensus over rational decision-making.

Structural Faults: These include insulation of the group, lack of impartial leadership, lack of norms requiring methodological procedures, and homogeneity of members' social backgrounds and ideology.

Provocative Contexts: High-stress situations from external threats, low self-esteem, recent failures, excessive complexity, and moral dilemmas, can precipitate Groupthink, as they heighten the urgency for agreement.

Understanding the antecedents can help in preventing Groupthink in religious settings:

High Cohesiveness: While community is vital in religious groups, it should not come at the cost of suppressing individual thought or inquiry.

Authoritarian Leadership: Leaders should facilitate open dialogue and encourage diverse interpretations rather than imposing their views as the only acceptable ones.

Insulation from External Influences: Communities should engage with, rather than isolate from, different viewpoints to enrich their understanding of the Bible.

Consequences of Groupthink

The consequences of Groupthink can be severe, impacting organizations, governments, and societies. These can be categorized as symptoms of Groupthink and symptoms of defective decision-making.

Symptoms of Groupthink

Overestimation of the group:

Illusion of invulnerability

Belief in the morality of the group

Closed-mindedness

Collective rationalization

Stereotypes of outgroups

Uniformity pressures

Self-censorship

Illusion of unanimity

Direct pressure

Mindguards

Symptoms of Defective Decision Making

Incomplete survey of alternatives

Incomplete survey of objectives

Failure to examine risks of preferred choice

Failure to reappraise

Poor information search

Selective information bias

Failure to develop a contingency plan

In conclusion, Groupthink is a powerful and potentially dangerous phenomenon that can lead groups to make irrational, dysfunctional, or ethically questionable decisions. Understanding its dynamics, antecedents, and consequences is crucial for leaders, decision-makers, and members of any group to foster a culture of open dialogue, critical analysis, and diverse perspectives to avert the pitfalls of conformity and collective oversights.

Preventing Groupthink Using Critical Thinking

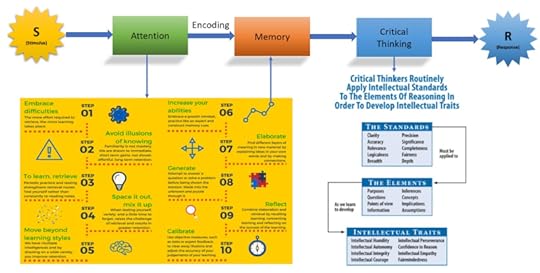

The Paul-Elder model of critical thinking is a comprehensive framework that encourages the development of reasoning skills to think more effectively. It comprises elements of thought, intellectual standards, and intellectual traits that can be instrumental in preventing Groupthink. By applying this model, each member of a group can contribute to a more open, analytical, and effective decision-making process, countering the common pitfalls of Groupthink.

Elements of Thought

Purpose: Group members should clearly define their purpose or goal. This helps in ensuring that the group's objective is to find the best possible solution or decision, rather than simply seeking agreement or cohesion.

Question at Issue: Identifying the central questions or problems being addressed ensures that the group remains focused on relevant considerations, thereby reducing the risk of straying into consensus-seeking for its own sake.

Information: Critical evaluation of all relevant information, including data and experiences, allows the group to consider a broad range of inputs and perspectives, minimizing the chances of uninformed or biased decisions.

Interpretation and Inference: Encouraging diverse interpretations and considering various inferences can prevent the premature convergence of ideas, enabling the group to explore a wider array of potential solutions.

Concepts: Clarifying underlying concepts and theories helps the group members to stay on the same page and avoids misunderstandings that can lead to uniformity without scrutiny.

Assumptions: Challenging the group’s assumptions can unearth unexamined beliefs and prevent the group from overlooking critical information or alternative viewpoints.

Implications and Consequences: Considering the broader implications and potential consequences of decisions can lead to more thoughtful and forward-looking conclusions, mitigating the shortsightedness often associated with Groupthink.

Intellectual Standards

Clarity: Ensuring that communication is clear and understood by all can prevent misunderstandings that might lead to uncritical conformity.

Accuracy: Focusing on accuracy helps in avoiding errors and ensures that decisions are based on reliable information.

Precision: Being precise with information and arguments helps in addressing the specific nuances of the decision at hand, avoiding vague consensus that might be poorly thought out.

Relevance: Maintaining relevance ensures that discussions and decisions are focused on the objective, reducing the likelihood of diverging into tangents that may lead to conformity pressures.

Depth: Considering the depth of issues helps in understanding the complexity of the problem, which is crucial for avoiding the oversimplification that can accompany Groupthink.

Breadth: Encouraging a breadth of perspectives can counter the uniformity of thought by bringing in diverse viewpoints and reducing the echo chamber effect.

Logic: Ensuring that the group’s reasoning is logical and coherent guards against the flawed justifications that can arise in Groupthink.

Intellectual Traits

Intellectual Humility: Acknowledging the limits of one’s knowledge can prevent the overconfidence that often contributes to Groupthink.

Intellectual Courage: Being willing to challenge the group’s consensus or popular opinions encourages a culture where all ideas are scrutinized, reducing the conformity pressure.

Intellectual Empathy: Understanding and considering the perspectives of all group members can ensure that minority viewpoints are not suppressed.

Intellectual Integrity: Commitment to applying the same standards of reasoning to oneself as to others helps in maintaining a consistent and unbiased approach to group decision-making.

Intellectual Perseverance: Persistence in seeking the best possible answer encourages thorough analysis and discourages the group from settling for easy consensus.

Confidence in Reason: The belief that through reasoned dialogue the best solution will emerge supports an environment where critical examination is valued over mere agreement.

Fair-mindedness: Being fair to all viewpoints encourages the consideration of all relevant perspectives and information, thereby countering the group’s tendency toward biased consensus.

By integrating the Paul-Elder model of critical thinking, group members can foster a culture of reasoned inquiry, robust debate, and open-mindedness, which are essential for preventing the narrow-minded consensus and flawed decision-making characteristic of Groupthink. This approach not only enhances the group’s ability to make sound decisions but also strengthens the individual members' critical thinking capabilities. While Groupthink can significantly impede the quality of biblical interpretation in religious denominations and churches, awareness and intentional countermeasures can foster an environment where the sacred texts are engaged with thoughtfully, openly, and profoundly. By valuing individual insight within the community context, religious groups can ensure that their collective interpretations remain vibrant, relevant, and spiritually nourishing.

March 18, 2024

The Evolution and Impact of Archaeological Practices in Biblical Studies

The Evolution and Impact of Archaeological Practices in Biblical Studies

By Dr. Roy Blizzard and Andrew Garza

The interesting, problematic dynamics between archaeology and biblical tales' interpretation give both an engaging environment for the biblical scholar, one which challenges preconceptions and always comes up with new understandings of the new and old before us. The development of new paradigms, since then, has given cause to doubt former and more dominant views of the practice, as the field of archaeology has in the past half-century undergone great shifts in paradigms. Archaeology and Biblical Narratives All of these methods and ways are a bridge between ancient and modern cultures to realize the historical context of the biblical event. Meticulous analysis of stratigraphic layers and pottery goes a long way in fixing an accurate date of the archaeological site that provides chronological background in light of which normally the stories and events as mentioned in the Bible get fixed. These are the concrete links with the past through artifacts, inscriptions, and monumental remains, which give us far more than a simple hint for understanding biblical stories and grounding them into reality. On the other hand, the challenge comes when archaeological finds either prove contrary to or challenge biblical and historical accounts. They allow the scholar to revisit his conventional reading of the data and look at things from a new perspective. This interaction between archaeology and theology calls us to read much more subtly and critically still the sacred text, and it calls us to regard most seriously the historical, cultural, and social contexts of the writers of the sacred texts.

Technological Advancements and Methodological Shifts

In fact, the last fifty years have really been a very important period during which dramatic technological achievements within the discipline of archaeology were being held. In the past fifty years, the arrival of tools such as the coming of radiocarbon dating, satellite images, and geophysical surveys has changed the exploration, excavation, and interpretation of any archaeological site. Such innovations have not only refined ways of dating but have also opened new vistas for the understanding of ancient landscapes, urban planning, and trade networks, giving a wider context within which to interpret the biblical world than this information. Modern archaeology has become more interdisciplinary in its approaches to study and practice. For example, archaeologists now have formed nomological networks by collaborating with geologists, biologists, chemists, and historians, among others, and many views on the multidimensional perception of artifacts and sites have emerged, increasing and enriching the interpretation of archaeological evidence. This has brought to light complex historical puzzles, clarifying issues ranging from ancient dietary practices to the economic conditions of Biblical times.

Ethical Considerations and Preservation

The evolution of archaeology also reflects a growing awareness of ethical considerations. Today, it is a huge question of treatment issues of human remains, repatriation of collections, and engagement of local communities, which have become central for guaranteeing respect in light of the cultural and historical importance of findings and sites. This focus on conservation further highlights a firm commitment to protecting this relic with enthusiasm equal to that of the find for the olden generations. Public Engagement and the Role of Education From that, public participation and education have democratized archaeology from its very stuffy and elite pursuits to a vibrant and accessible discipline. It is in fact through educational programs, museum exhibitions, and digital platforms that the past is increasingly brought to life for audiences around the world, increasingly holding greater access to the human past.

The Synergy Between Being an Archaeologist and Biblical Scholarship

It gives a Bible scholar an outstanding perspective from which to give interpretations of the scriptures, giving a solid, concrete link between the world of the texts and reality. This partnership of archaeology with biblical scholarship does indeed have relevance, insofar as it can help to ground the interpretation of the Bible in a historical real-world context—one that has subtlety with the word of God.

Role of Archaeological Excavation: This is because the archaeologists unearth the physical remains of civilizations since consigned to the dust of the earth; from every manner of household items to great temples, all of which can be used to give context to biblical stories. For example, in ancient Israelite cities, the Bible points towards architectural styles, city planning, practices of daily life, etc. With the help of archaeological excavations, these could help a scholar in reconstructing, in his mind, the setting of the biblical event.

Historical Validation: Archaeology presents the material culture, in the form of artifacts, inscriptions, and stratigraphy, which may be able to either confirm or challenge the written records of history within the Bible. Such finding evidence may support the historical narrations presented in the scriptures or, in some cases, call for a revision of some assumptions to guarantee the right interpretation of texts.

Understanding Ancient Cultures: Archaeology helps in understanding the cultural inclinations, religious practices, and socio-political aspects of ancient civilizations. Knowledge of the same helps Bible scholars understand the many subtleties of the scriptures, cultural to their times, which may escape them otherwise. With this cultural backdrop in mind, it can make all the difference regarding our understanding of many of these texts in the Bible.

Linguistic Insight: The importance that the ancient finds have, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, relates to a parallel link directly with the linguistic nature of the biblical texts. Archaeology had tried to work on decrypting these writings, and it gave Bible scholars critical insights into the language, idioms, and literary style of that age, enhancing the interpretation of the scriptures.

Chronological Frameworks: This will help place biblical events within accurate chronological frameworks from timelines of archaeological finds. The chronological framework will be able to help explain accurately the time and the reason behind certain biblical texts.

Archaeology as a Reflective Mirror: Arguably the most advantageous opportunity that opens up for a Bible scholar in the ambit of archaeology is the chance for him to be able to hold a reflective mirror to the scriptures. This is what makes scholars bring out that in their readings, whether they agree with the physical evidence presented and not only that but also remain open to any new revelation that may help to enlighten or bring more clarity to their understanding of the Bible. In essence, the interplay between archaeology and biblical scholarship is a dynamic and enriching dialogue. It inspires an even more engaging, better-informed activity with the Scriptures that has its grounding in the material, dusty reality of an archaeological dig site and lifts one's view of the Bible as a historical, cultural, and spiritual document. The true insights into them are what makes biblical interpretation not an exercise in theology but a vibrant exploration of the ancient world that gave its part to shaping the scriptures.

Monumental Remains

The monumental remains in archaeology, particularly in the context of the Middle East, underscore their significance in understanding historical and cultural developments. Here are the main points regarding the history and implications of finding monumental remains:

Historical Context:

Monumental remains, such as buildings, fortifications, statues, or inscriptions, are significant archaeological finds that provide insight into the architectural, artistic, and cultural practices of past civilizations.

Such remains often serve as landmarks of historical events, societal hierarchies, religious beliefs, and technological advancements.

Implications of Discovering Monumental Remains:

Cultural Insight: These remains offer a window into the daily lives, governance, and spiritual practices of ancient societies. They help historians and archaeologists reconstruct past environments, understand societal structures, and appreciate the aesthetic values of the civilizations.

Technological Understanding: The construction techniques, materials used, and architectural styles reflected in monumental remains reveal the technological prowess and innovative capabilities of ancient peoples.

Historical Narratives: Monumental remains can confirm historical accounts, clarify chronologies, and sometimes challenge existing historical narratives. They provide tangible evidence that can either corroborate or dispute written records.

Preservation of Heritage: The discovery and preservation of these remains are crucial for maintaining cultural heritage, providing educational resources, and promoting historical tourism, which can have significant economic and cultural benefits.

Interdisciplinary Research: Analyzing monumental remains often involves an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating fields like engineering, architecture, materials science, and history to fully understand their significance and construction.

Monumental remains are pivotal in piecing together the historical puzzle of human civilization. They stand as enduring testaments to the ingenuity, beliefs, and societal organization of our ancestors, offering profound insights into the past that continue to shape our understanding of history and culture.

The Western Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall is significant as a monumental remain within the context of archaeological and historical studies. Here are the key points addressed:

Historical Significance:

The Western Wall is one of the last remaining structures of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, which was expanded and refurbished by Herod the Great in the 1st century BCE and subsequently destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE.

It is considered the most sacred site recognized by the Jewish faith outside of the Temple Mount itself because it is the closest remaining vestige to the former Temple's Holy of Holies, which was the most sacred site in Judaism.

Implications of the Western Wall as a Monumental Remain:

Cultural and Religious Reverence: The Wall serves as a powerful symbol of Jewish endurance and spirituality. It is a focal point for Jewish prayer and pilgrimage, embodying the deep historical and religious connections to Jerusalem and the ancient Temple.

Archaeological and Historical Insights: As part of the larger Temple Mount complex, the Wall provides key insights into Herodian architecture, ancient construction techniques, and the historical landscape of Jerusalem. Its study contributes to our understanding of the socio-political and religious dynamics of the region during the Second Temple period.

Symbol of Identity and Memory: The Western Wall stands as a testament to the millennia-old Jewish connection to Jerusalem. It is a symbol of Jewish identity, national continuity, and the enduring hope for the reconstruction of the Temple, reflecting the historical and spiritual aspirations of the Jewish people.

Interfaith Significance: While primarily a Jewish site, the Wall also holds significance for Christians and Muslims, reflecting the complex tapestry of religious traditions and historical narratives that converge in Jerusalem, a city sacred to all three Abrahamic faiths.

The Western Wall's status as a monumental remain is not just about its physical presence; it's a living symbol of history, spirituality, and cultural identity. Its enduring significance is reinforced by the daily prayers of the faithful, the placement of prayer notes in its crevices, and its role in major Jewish festivals and life events, making it a vibrant, living connection to the past and a beacon of faith and tradition.

Artifactual Remains

The artifactual remains in archaeology shed light on their critical role in unraveling the intricacies of past civilizations. Here’s a summary of the main points regarding the history and implications of finding artifactual remains:

Historical Context:

Artifactual remains include any items created, used, or altered by humans, such as tools, pottery, jewelry, and everyday household objects. These artifacts are pivotal in archaeological studies as they provide direct evidence of human behavior, technological advancement, and artistic expression.

Implications of Discovering Artifactual Remains:

Cultural Understanding: These artifacts offer invaluable insights into the daily lives, social structures, economic systems, and cultural practices of ancient communities. They help in constructing a detailed and nuanced picture of past human life.

Technological and Artistic Insights: The study of artifactual remains illuminates the technological skills, artistic traditions, and material preferences of ancient peoples, reflecting their ingenuity, adaptability, and aesthetic sensibilities.

Chronological Framework: Artifacts play a crucial role in dating archaeological sites and understanding the temporal context of historical developments. They help in establishing chronologies and understanding the evolution of societies over time.

Interpretation of Past Behaviors: Through the examination of artifactual remains, archaeologists can infer the activities, rituals, and societal norms of ancient populations, offering clues to their beliefs, values, and social organization.

Preservation of Historical Narratives: Artifactual remains are tangible links to our past, preserving the legacy of cultures that may no longer exist. Their preservation and study enable the continuation of historical narratives and cultural memory.

The discovery and analysis of artifactual remains are fundamental to the field of archaeology, offering a tangible connection to the human past. These artifacts not only enhance our understanding of ancient societies but also help in preserving the diverse heritage of human civilization, contributing to our collective memory and historical identity.

Written Remains

The written remains in archaeology have a profound significance in understanding historical narratives and cultural developments. Here are the main points regarding the history and implications of finding written remains:

Historical Context:

Written remains, such as inscriptions, manuscripts, scrolls, and tablets, are invaluable for their direct transmission of information from the past, offering firsthand accounts, administrative records, literary works, and religious texts.

These artifacts can include a variety of languages and scripts, some of which have been deciphered through key archaeological discoveries like the Rosetta Stone.

Implications of Discovering Written Remains:

Linguistic and Textual Insights: Written artifacts are pivotal in the study of ancient languages, scripts, and textual traditions. They enable linguists and scholars to reconstruct lost languages, understand linguistic evolution, and gain insights into the literacy and educational practices of past societies.

Cultural and Historical Understanding: Written remains provide direct access to the thoughts, beliefs, practices, and historical events recorded by ancient people themselves. This can illuminate aspects of ancient life, from daily routines to significant historical events, and from governance systems to religious practices.

Chronological and Historical Accuracy: These texts can offer precise dates, names, and events, serving as invaluable tools for constructing accurate historical timelines and validating or challenging existing historical narratives.

Interdisciplinary Studies: The interpretation of ancient texts often requires an interdisciplinary approach, combining expertise in language, archaeology, history, and paleography. This collaborative effort can unravel complex historical puzzles and provide a comprehensive understanding of the past.

Preservation of Knowledge: Written remains are crucial for preserving the knowledge, wisdom, and literary output of ancient civilizations. They connect us directly with the intellectual, spiritual, and artistic endeavors of our ancestors, offering a legacy of human thought and experience.

The discovery of written remains is a gateway to the intellectual world of ancient civilizations, providing a direct voice from the past that enhances our understanding of historical contexts, cultural developments, and the human condition across millennia. These artifacts are indispensable for building a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of human history.

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, as written remains, highlight their significant contribution to our understanding of ancient texts, religious practices, and historical contexts. Here's a summary of the key points:

Historical Background:

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of Jewish texts discovered between 1947 and 1956 in the Qumran Caves near the Dead Sea. They consist of biblical manuscripts, sectarian writings, and apocryphal works, written mainly in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

Implications of the Dead Sea Scrolls:

Textual Insights: The scrolls have provided unprecedented insights into the textual development of the Hebrew Bible. They include the oldest known copies of the Old Testament texts, offering critical data for understanding the evolution of these sacred writings.

Sectarian and Theological Perspectives: Among the scrolls, some texts shed light on the beliefs, practices, and organizational structure of a Jewish sect, believed to be the Essenes. This information significantly enriches our understanding of the diversity within Second Temple Judaism.

Linguistic Contributions: The scrolls contribute to the study of ancient languages, particularly Hebrew and Aramaic, offering examples of linguistic forms, vocabulary, and script variations that were prevalent during the Second Temple period.

Historical Validation: The archaeological context of the scrolls, corroborated by historical and radiocarbon dating, establishes a firm timeline for their creation and use, providing a chronological anchor for the study of the late Second Temple period.

Scholarly Impact: The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has had a profound impact on biblical scholarship, prompting reevaluations of textual traditions, the history of Judaism, and the origins of Christianity. Their study continues to influence modern understanding of the Bible and ancient Jewish history.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are among the most important archaeological finds of the 20th century. Their discovery has dramatically impacted the fields of biblical studies, theology, and the history of ancient Judaism, offering a unique window into the religious life and practices of an ancient Jewish community and contributing significantly to our understanding of the historical context in which early Christian thought developed.

Conclusion

The relationship between archaeology and biblical studies is a testament to the ongoing quest for knowledge and truth. The advances in archaeological practices over the past fifty years have not only enriched our understanding of the past but also challenged us to view biblical narratives with fresh eyes, informed by tangible evidence and rigorous analysis. As we continue to unearth the physical remnants of ancient civilizations, we draw closer to the worlds in which the biblical texts were crafted, enhancing our appreciation of these sacred writings and the people they represent.

February 4, 2023

EXPLICATING THE LOGIC OF THE BIBLICAL TEXT

HIGH FIDELITY LEARNING

EXPLICATING THE LOGIC OF THE BIBLICAL TEXT

Andrew Garza, Msc Psy

High Fidelity, or Hi-Fi, audio refers to the high quality of sound reproduction in which the playback is very true to the original recording. This means that there is minimal noise or distortion. The term is commonly used to describe home audio systems of a certain quality, although some people believe that it should adhere to higher standards. In 1966, the German Institute for Standardization established standards for frequency response, distortion, noise, and other defects in an effort to standardize the term. High fidelity learning involves a student accurately reproducing the material taught by a teacher.

Over half of a century ago, in 1948, Claude Shannon published his epic paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Shannon had the foresight to overlay the subject of communication with a distinct partitioning into sources, source encoders, channel encoders, channels, and associated channel and source decoders. Shannon's ideas have implications that were (at least fifty years ago) well beyond the immediate goals of communication engineers and of Shannon himself. These include insights for linguists and for social scientists addressing broad communication issues. Thanks to Shannon, Wilbur Schramm, Carl Hovland, Kurt Lewin, Paul Lazarsfeld, and Harold Laswell each helped in the formation of institutes where scholars could pursue communication study programs full-time. Research in this field is extensive and scattered. Because communication is a basic, perhaps the basic, social process, it shares the interest and attention of all the Biblical and social sciences that are concerned with thinking.

Thinking has a logic, but not all thinking is logical. Logic can refer to the validity of an inference and can also refer to a coherent interrelation between elements in a system. It's the second part that I want to use concerning the interrelatedness of the elements of thought.

The logic of thought is as follows: whenever we think, we think for a PURPOSE within a POINT OF VIEW based on ASSUMPTIONS leading to IMPLICATIONS and consequences. We use CONCEPTS, ideas and theories to interpret INFORMATION in the form of data, facts, and experiences in order to answer QUESTIONS, solve problems, and resolve issues.

Reading, writing, speaking, and listening are modes of communication of thought and are all "dialogical" in nature. That is, in each case there are at least two logics involved, and there is an attempt being made by someone to translate one logic into the terms of another. A successful communication process occurs when the receiver understands the message (decodes the logic) just as the sender understood it (encoding of their logic). Of course, this does not happen at a 100% success rate as there are many factors involved in both the encoding and decoding processes and general “noise” in the system (signal-to-noise ratio). Other important noise variables affecting the success of the communication process include the “fields of experience.” The fields of experience factors are numerous, and the best way to categorize these factors would be language, culture, personal history, and geographical locations of the sender and receiver, respectively. The more of a shared variance between the participants’ fields of experience, the higher the probability of a successful communication process

What is the significance of this communication process to a student of the Biblical text? Where communication becomes part of our educational goal is in reading, writing, speaking, and listening. These are the four modalities of communication which are essential to education and each of them is a mode of reasoning. Each of them involves problems. Each of them is replete with critical thinking needs. Take the apparently simple matter of reading a chapter of the Biblical text. The author has developed his thinking in the book, has taken some ideas and in some way represented those ideas in extended form. Our job as a reader is to translate the meaning of the author into meanings that we can understand without any feedback. This is a complicated process requiring critical thinking every step along the way. What is the purpose for the book/chapter? What is the author trying to accomplish? What issues or problems are raised? What data, what experiences, what evidence are given? What concepts are used to organize this data, these experiences? How is the author thinking about the world? Is his thinking justified as far as we can see from our perspective? And how does he justify it from his perspective? How can we enter his perspective to appreciate what he has to say? All of these are the kinds of questions that a critical reader raises.

Furthermore, each of these dimensions of reasoning could be looked at from the point of view of the "perfections" of thought, those intellectual standards which individually or collectively apply to all reasoning. (Is it clear, precise, accurate, relevant, consistent, logical, broad enough, based on sound evidence, utilizing appropriate reasons, adequate to our purposes, and fair, given other possible ways of conceiving things?) And a critical reader in this sense is simply someone trying to come to terms with the text. So, if one is an uncritical reader, writer, speaker, or listener, one is not a good reader, writer, speaker, or listener at all. To do any of these well is to think critically while doing so and, at one and the same time, to solve specific problems of communication, hence, to effectively communicate.

In simple terms, communication involves the exchange of ideas between at least two people. When reading, the reader must understand the thoughts and reasoning of the author, and the critical reader must carefully analyze and decode the author's logic in order to analyze and evaluate and internalize the ideas presented in the text. This process of critical analysis allows the reader to create their own understanding of the text and its meanings, and to the best of their ability, to understand the meanings intended by the author. It can be argued that knowledge of Hebrew is indeed important in explicating the logic of the Bible, as it can provide a deeper understanding of the text and help to avoid misunderstandings that can occur due to language barriers.

“To do well in Biblical exegesis, I must begin to think Hebraically. I must not read the books of the Bible as a bunch of disconnected stuff to remember but as the thinking of a Hebrew scholar. I must myself begin to think like a Hebrew scholar. I must begin to be clear about Hebraic purposes (What are Biblical authors trying to accomplish?). I must begin to ask Hebraic questions (and recognize the Biblical questions being asked in the lectures and studies). I must begin to sift through Biblical information, drawing some Hebraic conclusions. I must begin to question where Biblical information comes from. I must notice the Hebraic interpretations that the author forms to give meaning to Biblical information. I must question those interpretations (at least sufficiently to understand them). I must begin to question the implications of various Biblical interpretations and begin to see how Hebraic authors’ reason to their conclusions. I must begin to look at the world as the Biblical authors do, to develop a Hebraic viewpoint. I will read each chapter in the Bible looking explicitly for the elements of thought in that chapter. I will actively ask (Biblical) questions from the critical thinking perspective. I will begin to pay attention to my own Biblical thinking in my everyday life. I will try, in short, to make Biblical thinking a more explicit and prominent part of my thinking.”

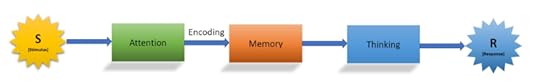

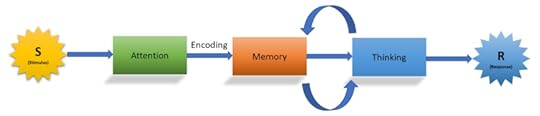

This overly simple information-processing model is an essential road map to thinking like a Bible scholar. The information-processing approach analyzes how individuals attend to information, encode it, store it, retrieve it, manipulate it, monitor it, and create strategies for handling it.

When various types of stimuli are detected, the brain constructs useful information about the world on the basis of what has been detected, and we use this constructed information to guide ourselves through the world around us. Attention is the focusing of mental resources on certain but not all stimuli. Attention improves cognitive processing for many tasks. At any one time, though, people can pay attention to only a limited amount of information which requires certain strategies to overcome the limitation.

Memory is the retention of information over time. Information that is attended to must be encoded by transducing visual information, auditory information, chemical information, or haptic information into the language of the brain which involves chemical and electrical changes of neuronal synapses. Depending on which memory system is activated (short-term and long-term), storage can take place for a short duration, or up to a lifetime. Sensory memory has a large capacity and is of a short duration. Short-term memory has a small capacity and short duration. Long-term memory is an almost unlimited amount of capacity but being very “stingy,” requires certain strategies to insure retention.

Thinking is the mental manipulation of representations of knowledge about the world stored in memory. Thinking allows us to take information, consider it, and use it to build models of the world, set goals, and plan our actions accordingly.

Schemas are organized bodies of information stored in memory. The concept was first pioneered by Sir Frederic Bartlett and best demonstrated by the party game “telephone” based on his research. Schemas are based on prior categorization of object, places, people, and other things affect what we attend to, how it is encoded, how it is stored, and how it is recalled.

To explicate the logic of an author (or sender) schemas must first be formed in the mind of the reader (receiver). Not only must data be stored in memory, but in a “logical” or systematic fashion. At this point, a distinction must be made between components of data and what are the results of manipulation of data. Data can be in the form of facts. Facts are verifiable information and can be the weight of an atom or the date of the end of World War II. Opinions are or should be well reasoned conclusions based upon facts. Beliefs are conclusions not based upon facts and are unverifiable or unfalsifiable. And prejudicial thought is poorly reasoned thought based on facts and can be falsified.

"Make It Stick" by Peter Brown, Henry Roeddiger, and Mark McDaniel outlines several memory techniques that can help improve long-term retention of information:

Spaced Repetition: Spacing out studying sessions over time rather than cramming helps to reinforce memories and increase long-term retention.

Interleaving: Mixing up the subjects you study helps to promote deeper understanding and better retention.

Elaboration: Relating new information to what you already know helps to create connections in your memory, making it easier to recall later.

Self-Explanation: Explaining material to yourself helps to reinforce understanding and aids in the creation of memory connections.

Generation: Creating new material from what you have learned, such as summarizing or generating questions, helps to promote deeper understanding and stronger memory.

Retrieval Practice: Quizzing yourself and practicing recalling information helps to strengthen memory and increase long-term retention.

These techniques can be combined and tailored to best fit the individual learner's needs and preferences.

Modern notion of knowledge is shifting from the ability to recall information to the ability to find and use information. Just as all thought has a logic, but not all thinking is logical, critical thinking requires higher order thinking skills, but higher order thinking skills are not critical thinking. Higher order thinking skills are necessary, but not sufficient regarding critical thinking. Bloom’s taxonomy is an excellent source for defining higher order thinking skills that are required in critical thinking.

Critical thinking involves actively and objectively evaluating information and arguments in order to arrive at a well-supported conclusion. It involves the examination of the clarity, accuracy, relevance, depth, breadth, and logicalness of thoughts and ideas, and the recognition that all reasoning is based on assumptions and perspectives. Additionally, critical thinking requires recognizing that all reasoning is directed towards specific goals and objectives, and that data and information must be interpreted within their appropriate context. To think critically, one must be aware of the possible issues and problems that can arise in thinking and be willing to question and assess the standards and assumptions that underlie thought and understanding in any given field.

Here is a correspondence between Bloom’s Taxonomy and the Paul-Elder Critical Thinking model.

I suggest that to use the Paul-Elder model of critical thinking to explicate the logic of the books of the Bible, that each book be analyzed for its purpose, key questions, key information, key concepts, main inferences, main assumptions, implications, and point of view. The person performing the analysis then uses the intellectual standards of clarity, accuracy, precision, breadth, depth, logicalness, relevance, significance, and fairness. In addition, the person performing the analysis to explicate the logic of the Bible needs to possess the intellectual traits of humility, autonomy, integrity, courage, perseverance, empathy, confidence in reason, and fairmindedness.

This model can result in dialog rather than debate when it comes to difficult issues, doctrines, and interpretations of the Biblical text. The following is a fictional account of a dialogical discussion:

Once upon a time, there were two individuals, named Tom and Jane, who were both trained in the Paul-Elder model of critical thinking. They were discussing a controversial theological doctrine, and both were eager to engage in a dialogical manner.

Tom began by presenting his perspective on the doctrine, explaining his reasoning and evidence for his stance. Jane listened attentively and acknowledged the reasonableness of Tom's argument. However, she pointed out that she had some concerns about the accuracy of some of the evidence he had presented.

Tom responded by demonstrating intellectual humility and fairness, acknowledging that there may be some gaps in his knowledge and that he was open to further evaluation. He appreciated Jane's observations and asked her to elaborate on her concerns.

Jane explained that she had some doubts about the historical context of the evidence that Tom was using and whether it was relevant to the current discussion. She also mentioned that she felt that the evidence lacked depth and breadth, and that she would like to see a more comprehensive examination of the issue.

Tom responded by demonstrating intellectual courage and integrity. He acknowledged that Jane's observations were valid and that he needed to do further research in order to provide a more comprehensive examination of the issue. He also expressed confidence in reason and intellectual perseverance, indicating that he was willing to engage in a thorough evaluation of the issue in order to arrive at a more informed and fair-minded conclusion.

In the end, both Tom and Jane demonstrated intellectual empathy and fair-mindedness as they continued their discussion, exploring the doctrine from different angles and evaluating it using the intellectual standards of clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, significance, logicalness, breadth, depth, and fairness. They both left the discussion with a deeper understanding of the issue and a greater appreciation for each other's perspectives.

Alfred Adler, the Austrian psychologist, believed that the purpose of reading a book is to gain a better understanding of the world and of oneself. He emphasized the importance of active reading, where the reader engages with the text and critically evaluates the author's ideas and arguments. Adler recommended that readers ask questions, make connections to their own experiences, and consider the wider social and cultural context in which the book was written. By doing so, Adler believed that readers could gain new insights, expand their knowledge, and develop their own thinking and problem-solving skills.

Adler advocated the following steps when reading a book:

Preparation: Before reading, Adler suggested that readers gather information about the author, the historical context, and the book's content and purpose. This helps to establish a framework for understanding the text.

Active Reading: Adler encouraged readers to engage actively with the text by highlighting, taking notes, and asking questions. This helps to ensure that the reader is paying attention and actively processing the information.

Critical Evaluation: Adler emphasized the importance of critically evaluating the author's ideas and arguments. This means considering the evidence, reasoning, and perspectives presented in the text and making judgments about their validity.

Reflection: After reading, Adler recommended that readers reflect on what they have learned and how it relates to their own experiences and knowledge. This helps to internalize the information and make it more meaningful.

Application: Adler encouraged readers to apply what they have learned by using it to solve problems, make decisions, and improve their own lives and the world around them.

By following these steps, Adler believed that readers could gain a deeper and more meaningful understanding of the books they read.

Knowing Hebrew can be helpful in explicating the logic of the Bible, but it is necessary. While having knowledge of the original language of the Old Testament can provide a deeper understanding of the text, there are many resources and tools available in other languages that can assist in the critical analysis of the Bible. These include translated versions, commentaries, and biblical studies that provide insight into the cultural, historical, and literary context of the text.

Additionally, critical thinking and analysis skills are important in explicating the logic of the Bible in addition to language proficiency. The Paul-Eder critical thinking model, for example, can be applied regardless of the language of the text, and focuses on evaluating the arguments, evidence, assumptions, and conclusions presented in the text.

In conclusion, while knowledge of Hebrew can be useful, and it is a determining factor in the ability to explicate the logic of the Bible, a combination of critical thinking skills and access to resources in other languages can provide a solid foundation for a thorough analysis of the text.

Putting It All Together Using the Paul-Elder Model of Critical Thinking

And “How to Read a Book”

By Alfred Adler

Analysis: Rules for Finding What a Book or Chapter is About

Briefly read the book/chapter and classify the book/chapter according to kind and subject matter.

State what the PURPOSE of the whole book/chapter is about with the utmost brevity.

Can you state the purpose clearly?

Logically, what is the objective of the reasoning?

Are you precise?

Have you identified the most significant problem?

Enumerate its major parts in their order and relation and analyze these parts as you have analyzed the whole.

Define the QUESTION or QUESTIONS the author is trying to answer.

Are there other ways to think about the question more precisely?

Can you divide the question into relevant sub-questions?

Is this a question that has one right answer, or can there be more than one reasonable answer to be more in-depth?

Which of the significant facts are most important?

Does this question require judgment rather than facts alone?

Interpretation: Rules for Interpreting a Book/chapter's Content

Reread the chapter/book to grasp the author's leading propositions by dealing with the most important INFORMATION

To what extent is the reasoning supported by relevant data?

Do the data suggest explanations that logically differ from those given?

How clear, accurate, and relevant are the data to the question at issue?

Was sufficient data gathered to reaching a reasonable conclusion?

Come to terms with the author by interpreting the key CONCEPTS.

What relevant key concepts and theories are guiding the reasoning?

What alternative explanations might be possible, given these concepts and theories?

Are you clear and precise in using these concepts and theories in your reasoning?

Know the author's INFERENCES, by finding them in, or constructing them out of, sequences of sentences.

To what extent do the data support the conclusions?

Are the inferences consistent with each other?

Are there other reasonable inferences that should be considered?

Determine which of the QUESTIONS the author has answered, and which not; and of the latter, decide which the author knew he had failed to solve.

III. Criticism: Rules for Criticizing a Book/chapter as a Communication of Knowledge

General Maxims of Intellectual Etiquette

Exercise intellectual humility by not engaging in criticism until you have completed your outline and your interpretation of the book/chapter. (Do not say you agree, disagree, or suspend judgment, until you can say "I understand.")

Exercise intellectual integrity by not disagreeing disputatiously or contentiously and demonstrating that you recognize the difference between knowledge and mere personal opinion by presenting good reasons for any critical judgment you make.

Exercise intellectual empathy by actively taking the point-of-view of the author.

Special Criteria for Points of Criticism

Identify the author’s ASSUMPTIONS.

What assumptions were underlying the INFERENCES?

Are the assumptions justified?

How were the assumptions shaping the point of view?

Which of the assumptions might reasonably be questioned?

Identify the author’s POINT OF VIEW.

What is the point of view?

What insights is it based on?

What are its weaknesses?

What other points of view should be considered in reasoning through this problem?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of these viewpoints?

Are you fairmindedly considering the insights behind these viewpoints?

Identify the IMPLICATIONS of the reasoning.

What implications and consequences follow from the reasoning?

If we accept this line of reasoning, what implications or consequences are likely?

Show wherein the author's analysis or account is incomplete.

May 8, 2022

A New Testament Survey: The Romans, The Jews, and the Christians Paperback

A New Testament Survey: The Romans, The Jews, and the Christians

"The purpose of this book is to acquaint the student with the historical, geographical, political, and religious context that gave birth to the document that we call the New Testament or the New Covenant. This is a survey. If you have had a survey course, you know that this is the kind of a study where you give a cursory perusal to the material. Instead of a deep, theological and historical study, you're getting a rather broad picture. That is what this kind of book is designed to be-just a survey. That's not the way that I'm going to write it. I will give special attention to the life and teaching of Jesus in its proper historical, cultural, and linguistically context. I then will look at this movement that centers around Jesus with him considering himself to be the center of a new movement that he calls "the Kingdom". I want to pay special attention to it as we see it in its early years on Hebrew soil. Then I want to study the development of that movement as it embraces the Gentile world and moves to the West as a result of missionary activities of individuals like Paul, Barnabas, and others."

I’m proud to present to the general public this work that was originally taught in the ’80s and ’90s under the scholarship of Dr. Roy Blizzard in a publicly taught course entitled “New Testament Survey.” The following material was transcribed off several tapes that recorded this event live. Comments and questions from those in attendance have been preserved to answer possible questions the reader may ask while studying this material. I have done to the best of my ability, in conference with Dr. Blizzard, and in my own personal research and study, to spell the names of the individuals, cities, and Greek and Hebrew references correctly and consistently with present-day scholarship. If there are any problems with any of the spelling, the fault lies in my presentation and not in the original presentation of the material.

Barry Fike

Minister church of Christ

April 9, 2022

More Science and the Bible

Science and the Bible Lecture

There are a number of issues and questions that have actually become problems confronting our society today. An interesting fact is that for several of the major issues (which we are not going into today – but, for example, birth control, abortion, homosexuality and gay marriage, sex education, divorce and remarriage, evolution versus creation science) that there is a solution to all of these problems and it, interestingly enough, is to be found in Hebrew.

We are going to focus briefly just on the latter and suffice to say that a revolution is taking place today in the halls of anthropology. Recent archaeological, anthropological, scientific studies and researches have changed the way we think about human origins.

Before modern times, the Bible was considered to be the inspired and infallible word of God and the final authority on most any subject. But, in the 17-19 centuries in Europe, we had a rise of rationalism with improved educational procedures and expeditional and laboratory methods of research that brought everything into question. It became fashionable to investigate and speculate on almost everything, including the Bible. With the journeys and postulations of Charles Darwin and others, many of their postulations flew in the face of fundamental Christian theology. Christians just took the Bible, read it and believed what it said because they considered it the final authority.

Many of the hypotheses, especially those proposed by Darwin, flew in the face of Christian theology and conservative Christian theologians were forced to develop their own theories in response to those they considered challenging to the Biblical text.

Darwinism was popularly known as evolution, although that is a misnomer. Evolution simply means change. If you don’t believe in change, take a good look in the mirror the first thing when you get up in the morning.

What Darwin proposed was actually transformism. That assumes an evolutionary development from a lower form of life to a higher form of life crossing order lines. As you know, everything is divided into seven major levels or categories: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus and Species. One can have a change or mutation within family, genus and species, but that is simply a mutation. It is only when one crosses order lines that you have the development from a lower form of life to a higher one. With transformism, we were taught that man was the end product of a long line of development from Ramipithicus, Dryopithicus, Aegyptopithecus zeuxis, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Australopithecus, Pithecanthropus, Neanderthal, Cro-Magnon, and finally Homosapien sapien. This long line of evolutionary development was resultant from beneficial mutations.

In reaction, Christian fundamentalists developed their own pseudo scientific theory, the principle one being Creationism or Creation Science. It appeared in two forms.

The first is known as the Gap Theory which assumed prior creation and a gap between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 focusing on the word became – and the earth became without form and void. Then, God began a long process of creation anew.

The next theory was known as Spontaneous Creation. The principal advocate was the noted ornithologist Dr. Douglass Dewar who wrote a well-known book on the subject entitled The Transformist Illusion. In his book, he categorized every known fossil in paleontology, the number of fossils in each category and attempted to demonstrate that from the paleontological record, there was no evidence of an evolutionary development from a lower form of life to a higher form of life moving across order lines. He proposed a theory known as Spontaneous Creation. His hypothesis included the various geological ages but then he added that at such a time as the climactic conditions were conducive to the sustenance of certain life forms, they just spontaneously appeared.

Another principal theory was called Deistic evolution, which is about as close to true intelligent design as you can get. This hypothesis was proposed by one of my good friends and colleagues, Dr. C.C. Crawford who was for a number of years the Chairman of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Texas at El Paso. His hypothesis included all of the geological ages but ascribed causation to God.

The following file is from a dissertation by Dr. Roy Blizzard for an M.A. degree from Eastern New Mexico University in Portales, New Mexico.

Download Science and the Bible

February 6, 2021

Dr. Roy Blizzard

Dr. Roy B. Blizzard is President of Bible Scholars, a Texas-based organization dedicated to biblical research and education.

A native of Joplin, Missouri, Dr. Blizzard attended Oklahoma Military Academy and has a B.A. degree from Philips University in Enid, Oklahoma. He has an M.A. degree from Eastern New Mexico University in Portales, New Mexico, an M.A. degree from the University of Texas at Austin, and a Ph.D. in Hebrew Studies from the University of Texas at Austin.

From 1968 to June 1974, he was an instructor in Hebrew, Biblical History and Biblical Archaeology at the University of Texas at Austin.

Dr. Blizzard studied at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel, in the summer of 1966. In the summer of 1973, he worked on the archaeological excavations at Tel Qasile, where he excavated a Philistine Temple dating from 1200 B.C. In 1968, 1971 and 1972, he worked on the excavations at the Western Wall, or "Wailing Wall," at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

Since then, Dr. Blizzard has spent much of his time in Israel and the Middle East in study and research. He was a licensed guide in Israel and has directed numerous Historical and Archaeological Study Seminars to Israel, as well as to Jordan, Egypt, Turkey, Greece, and Italy.

Dr. Blizzard hosted over 500 television programs about Israel and Judaism for various television networks and is a frequent television and radio guest.

He is the author of Let Judah Go Up First, and the co-author of Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus. He is also the author of Tithing, Giving and Prosperity, The Passover Haggadah for Christians and Jews, The Mountain of the Lord, Mishnah and the Words of Jesus, Jesus the Rabbi and His Rabbinic Method of Teaching, as well as many other articles and lecture series. All of his programs and offerings are available at www.biblescholars.org.

Dr. Blizzard is nationally certified as an educator in Marriage and Family relationships and human sexuality. He is a Diplomate with the American Board of Sexology and continues to conduct a private practice in the field of sex education and therapy.

December 28, 2020

Medical GoFundMe Update

This is an announcement to inform you as followers of Bible Scholars, that Dr. Roy Blizzard is in dire need of having medical procedures performed to renew his teeth, hearing and vision. The estimated cost of these procedures is $53,000! So far we have raised about $9700. I think that all of us have benefited from the scholarship of Dr. Blizzard that we could not get from any other Bible scholar. Please consider helping to pay Dr. Blizzard back by helping him with his medical expenses. Here is the link to the GoFundMe site setup for Dr. Blizzard: GoFundMe. We need to hit the target of $50,000. If you are sending a check via Fedex, please contact us directly.

Dr. Roy Blizzard

2200 4th Ave. #212

Canyon, Texas 79015.

My sincere thanks,

Andrew Garza

Bible Scholars

The Newer Testament

“Rather than employing the standard translation technique of simply selecting the most appropriate English word for the Greek," noted Young, "I asked the question, ‘What is the Hebrew thought and wording underpinning the Greek text?’”

Using this method, his text reconstructs the Hebrew sources, language and mindset behind the early church and its foundational documents.

“Readers will now hear what first century listeners in ancient Israel would have heard because the translation brings to light the Jewish cultural, linguistic and spiritual setting of Jesus as a Jew,” Young said.

Jerusalem Post Article

Please go to www.hebrewheritagebible.com or www.bradyoung.org for more information.

Many Thanks

Bible Scholars on behalf of Dr. Roy Blizzard would like to express thanks for all of the support for 2020. Many of the bills have been taken care of, the only thing left is some more dental work. Prayers and support will be greatly appreciated for 2021. As for 2021, we at Bible Scholars would like to extend a Happy and Prosperous New Year!

December 20, 2020

David Flusser on the Historical Jesus: An Interview with Roy Blizzard Transcript

Blizzard: Professor Flusser, of all the many books that you have written, I think my favorite one is the book that you wrote on Jesus, just entitled Jesus. From your many years of research into the life and the words of Jesus, what kind of mental image do you have in your mind of Jesus?

Flusser: I think that the Jewish philosopher [Martin] Buber was right when he said that we can hear from the Gospels Jesus’ own voice when we know how to hear and he made this movement [Flusser puts his hand to his ear] and he said once to me, “And therefore when we read the Gospels then we can hear his voice and recognize his personality.” It is impossible to define Jesus’ personality and Jesus’ claims completely clearly because he is unique in the whole world. But one thing is clear: that he was both a Jewish teacher and a Jewish leader and that he is seen having a special contact between himself and God and that he thought that he will return as the savior. But there is a connection between his teaching and between his person because he is the center of the message of the Kingdom of Heaven. And so I think that, as Buber said, we can hear his voice and we can do it instinctively, but we can also do it in a far better way when we study the Gospels on the Jewish background, or even more when we see Jesus as being a part of Judaism of his days. It is not only important for the understanding of the words of Jesus and of his message and of the meaning of his person, but it is also important to study such Jewish sources which don’t directly explain a special saying of Jesus. It means you have to see Jesus’ person and Jesus’ teaching in the Judaism of his days and as a part of Judaism. Even sometimes it happens that we can, with the help of Jesus’ words, reconstruct Judaism of his days. So there is here a reciprocity.

Blizzard: Now this is interesting: You keep using the term “Judaism,” and I know that you are one of the foremost scholars in the world today in the New Testament. You have an extensive background in the Greek text of the New Testament, and yet you use the term “Judaism” and when I think of Judaism I usually think of the Semitic background, and I know that you have also written extensively about the Semitic background of the Gospels. And that leads me to ask the question, as a Jew in the first century just what language did Jesus speak?

Flusser: It is very improbable—we don’t speak of his omniscience—that he has spoken Greek. I know that there are also, even today, some scholars that think that he has spoken Greek. That is very improbable. He knew both languages of the Land: both Aramaic and Hebrew. But when he taught, he taught clearly only in Hebrew. For instance, the saying Kingdom of Heaven doesn’t exist in Aramaic. All the parables in the rabbinic literature are in Hebrew. And when you have some words in Aramaic in the New Testament they are mostly...they are all as far as I see in Mark. I have my personal doubts if this was not done by Mark himself who was a Jew of the dispersion who wanted to make a kind of couleur locale and put the Aramaic—but even there the Aramaic is always translated. And my experience is that it is impossible to translate some of the words of Jesus into Aramaic. The mistake about the Aramaic background of the New Testament arose in the sixteenth century when for the first time the Syriac translation of the New Testament was brought to Antwerp then they decided—and even today there are such men—that this was the original language of Jesus. Only later another scholar four hundred years ago in Leiden in the Netherlands discovered that the Syriac is not identical with the Aramaic of Eretz Israel or Palestine. But meanwhile, when we study not only the rabbinic literature but even the Dead Sea Scrolls, we see that from the time of the Maccabees the language of the Jews was Hebrew. Also the discovery of the so-called Ecclesiasticus or Ben Sira, one of the apocryphal books: it was written in Hebrew. So we see that even if Jesus said something in his time in Aramaic when he taught, it was evidently at the same moment translated into Hebrew, because from this time we have, with the exception of one man who came from Babylon, as far as I see really no sayings no teaching in Aramaic. Only later Aramaic became the important language. It is interesting also to see that Delitzch, who translated so well the New Testament into Hebrew with the help of a Jewish scholar, that he thought that the language [of Jesus] was Hebrew. His disciple, the Swedish [Lutheran] Gustaf Dalman, in his Words of Jesus, thought again that it was Aramaic, but most of his examples are in Hebrew. So I know that it is far more agreeable to translate Jesus words in Aramaic [in the eyes] of modern scholars, than to accept the simple fact that Jesus has spoken Hebrew and that his teaching was in Hebrew. It doesn’t mean that when he has gone to buy fish he hasn’t spoken also Aramaic. All the Jewish prayers from his time, with one exception (the Kaddish), all are in Hebrew, and there are not even Aramaic words as in the Talmud the saying that you have to pray in Hebrew because the angels don’t understand Aramaic. And when we find in the...ehhh...today, it is very easy to say that Aramaic was the language of Jesus when you don’t know the sources. You get always churchmen, for instance it is written that Matthew has written his Gospel in Hebrew: when you translate the word Hebrew by Aramaic then by the same way you can translate the word English as being Dutch. This no man would do. I don’t know why they decided the decision. As I said in the Maccabean time already in the writing of the second century before Christ we read that it is not true that the Jews speak Syriac (it means Aramaic) they speak another language (it means they speak and write in Hebrew) [Flusser refers her to the Letter of Aristeas §11]. That there are parts in Aramaic in the Old Testament: all these parts are from the time before the Maccabean revolt and they chose—because before the Aramaic was the natural language of the Persian empire—and later the Hebrew language was resuscitated and only later, some centuries after Jesus, the Aramaic became prevalent which is probably the consequence of the cultural crisis after the destruction of the Temple.

Blizzard: Now I know too that there are a lot of Bible colleges and seminaries in the United States who believe that Jesus actually spoke Greek and the Gospels were written in Greek, the whole New Testament for that matter. How did this Greek theory get started?

Flusser: This Greek theory: it is incomprehensible that it exists until today. I have heard from a Swedish scholar that he thought also that Jesus has spoken Greek. I understand this, because I know that it is not so easy for Gentiles to accept the thorough Jewishness of Jesus. Because then it would mean that they had received a foreign god and not their own ancient pagan gods. So they have to assimilate Jesus to the Greek gods. So they invent the idea that it was less Jewish and the tradition was Greek. It is completely impossible to think in this way especially about the first three Gospels, the so-called Synoptic Gospels. We can easily—more or less easily—discern what is the Hebrew wording behind, and where it was written in Greek. Because our Gospels were written, were composed or translated from Hebrew, and by redactional work were transformed into, for the Greek world. It seems to me to be relevant that when you study the Gospels then you can decide very often where a saying is more original and what was restyled in Greek. And very often you feel far better in the Hebrew form of a saying than in the later rewritten Greek form. And this is important because—it seems to me important—because this makes for the possibility to reach good results in the Quest for the Historical Jesus. Very often—and I dare to say it—very often you see that only in such saying, such forms of a saying, where it is more Greek there is more tension between Jesus and his community and the Gentiles. It means the restoration [?] beginnings of this [?] development is the same thing. As far as you depart from the Hebrew background of the Gospels as far as you go farther from the Jewish origin of the Gospel and of the Jewishness of Jesus by this I would even say you betray Jesus himself.

Blizzard: You were talking about the Greek theory: how it was difficult for you to understand that anybody could come up with it in the first place and am I correct in understanding that the Greek theory basically had its origin in the German school that gave us higher biblical criticism about three hundred years ago?

Flusser: I think that today there is a famous German scholar who exaggerates the Greek influence upon ancient Judaism in order to make ancient Judaism more Greek and today they have their support in the archives of Bar Kochba, of the Jewish pseudo-Messiah, where you have letters in Greek and in Aramaic and in Hebrew and so they think they can renew this strange story. But what I wanted to say is that in order to understand the New Testament and especially the Gospels you have to know thoroughly the Greek spoken in the time of Jesus. Some...because even the Greek is not the Classical Greek it is a kind of lower popular Greek. Both the Jews in the Diaspora and the early Christians have written literary works in such a Greek in which no normal author has spoken, no normal pagan author has written. It shows that it was a very popular Greek. I will give you an example: you know the word ballistics. Ballistics is from the Greek word βάλλω (ballō)—it means “to throw.” But in the Hellenistic lower Greek ballō means “to put.” Therefore when you translate wrongly the word ballō or ballistic not as “to put,” then you misunderstand even the Hebrew background. And as to the Hebrew this will be a task of very extensive scholarship to see...you have to learn the development of the Hebrew in the time of Jesus. Because you have the biblical Hebrew, the Hebrew of the prayers, you have more ancient Hebrew, and for instance the main books written in the rabbinic literature are—even if they are Hebrew— are in a later Hebrew than the Hebrew of Jesus. I can personally recognize a saying of a Jewish rabbi if it is from the first or second century or if it is from the fourth or fifth century. So the study of the Hebrew background of the Gospels helps us also for the study of the language of Jesus time. It is even possible that the Hebrew which is behind the Gospels is a mixture or a kind of synthesis between the biblical Hebrew and the high Hebrew of his days. It means sometimes the rabbinic Hebrew helps, sometimes even the Dead Sea Scrolls help, sometimes the biblical Hebrew helps. So we have here a translation and elaboration of Hebrew documents which were written from the time for which we have not very much material, especially because the Dead Sea...so-called, the famous Dead Sea Scrolls, are written in a pseudo-high Hebrew which was not written normally. So we have here to mobilize all our spiritual forces and all all our knowledge even to reconstruct or to see what is behind a word or two words of Jesus. That in the case of Jesus it is important to do such a work we know because Jesus’ words are a hidden treasure which you have, therefore, to bring from the earth.

Blizzard: Amen! Let me just ask you this question. Now this reflects my own personal feeling: would you go so far as to say with me that without a knowledge of Greek and that without a knowledge of Hebrew that it’s almost impossible for the individual to understand the words of Jesus as we have them recorded....