Peter Sims's Blog, page 3

March 27, 2013

Why Google CEO Page should friend Amazon’s Bezos

Published originally on MarketWatch.

SAN FRANCISCO (MarketWatch) — Google Inc. has reached another fascinating period of its growth and evolution.

Three years ago, the Internet giant risked becoming the next Microsoft as it became more political and bureaucratic on the back of astronomical growth. But Larry Page’s return as CEO has brought welcomed product focus, leadership, and accountability, and the company attracts and retains some of the best engineers in the world. These factors and great profits have taken Google’s GOOG -0.91% stock to record highs.

Yet one of the most important questions among Google insiders will be whether Page & Co. can embrace and institutionalize a culture of experimental innovation that made Google, well, Google in the first place.

For answers, they can look north to Seattle, where Amazon.com AMZN +1.91% routinely pioneers, reinvents, and evolves.

While Amazon founder Jeff Bezos clearly banks on the role of significant inventions, such as the Kindle, he has created a culture of experimental innovation at Amazon better than any other current CEO. (It helps that Bezos still owns more than 19% of the company.)

For example, when Bezos and his “S Team” at Amazon (short for “senior team”) consider a new opportunity, they do not frame the decision-making process around being able to earn hundreds of millions of dollars. Instead, they ask whether they think the opportunity could generate at least $10 million in revenue, and if they get excited about their hunch, they will assign some of their best intrapreneurs to the project.

Reuters Jeff Bezos.

As Bezos has often underscored: You can’t put into an Excel spreadsheet how customers will respond to a new idea.

Amazon’s strategy and decision-making process starts (and perhaps ends) with improving the customer experience. Every important meeting, project, or initiative at Amazon begins with a discussion of how the ideas will ultimately benefit customers.

Bezos and team, in fact, constantly experiment in a very strategic and incremental way to mitigate risks. There’s a lot of internal experimentation, which is where the insights about the problems and needs served by Amazon Web Services (AWS) originated. Google is trying to catch up to Amazon in cloud computing, and it’s likely too late.

Amazon’s incentive and reward systems reflect the importance of learning and discovery throughout the organization. Employee reviews include a section on what was learned from trying experiments, regardless of success or failure. That’s the power of a strong culture.

As my partner Casey Haskins, founding CEO of BLKSHP Innovation often says, “You are what you measure.”

Moving ahead

The primary innovation challenge for Page and Google going forward will be to create a strong culture that utilizes Google’s immense assets, insights, and platform for experimentation and discovery, as well as monetization. You can’t have one without the other.

Reuters

Larry Page.

Google execs are grateful that Page has brought renewed product focus and leadership, while eliminating inefficient bureaucracy and politics — yet Google is also a far less-experimental company and culture than it was even five years ago. Page and Google co-founder Sergey Brin increasingly look to the top-secret Google X Lab, home of a number of brilliant inventors and engineers led by Brin, for the company’s innovations. (Google X is where the driverless car project is housed.)

Nowadays, there isn’t an example of a company that relied on great inventors to produce lasting and sustainable innovation. As Haas School of Business professor Henry Chesbrough has documented well, centralized R&D, such as at Bell Labs and Xerox PARC, has given way to an era of open innovation.

This would hardly be news to Page, but creating a culture that balances entrepreneurial discovery and ruthless execution is extremely difficult.

Amazon has consistently struck that balance.

The advantage that Page and Brin appear to have is the same quality Bezos has in spades. All three executives have extremely curious and pioneering minds, perhaps dating back to their Montessori schooling, and their respective experiences building Google and Amazon exemplify creativity and invention through discovery and learning.

As Bezos has said, “What is dangerous is not to evolve.” If Page and Bezos are able to create cultures and leadership cohorts that can continue to evolve long after they step down, then they truly have built something to last.

Peter Sims (www.petersims.com)is the author of “Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries,” and founder of The BLKSHP Enterprises.

February 11, 2013

The Little “Nudges” that Would Make Even Churchill Proud

Last week, thanks to Kieron Boyle, Head of Social Finance and Investment at the UK Cabinet Office, who I was introduced to by Jonathan Greenblatt, head of the White House Office of Social Innovation and special assistant to President Obama, I had the privilege of visiting 10 Downing Street with a group of BLK SHP from the U.S. and the U.K. to discuss innovation, entrepreneurship, and social entrepreneurship with senior advisers to the Prime Minister and the UK Cabinet. It was a fascinating visit. As England teeters on the verge of a triple-dip recession, I actually came away inspired by the creative approaches and experiments leaders and people are now taking there. What follows below are some synthesized observations and insights.

Originally published on Forbes.

If there’s a bell curve of risk aversion by sector, government and philanthropy are at the far right end (by far). A high-level American diplomat recently described to me the risk aversion in Washington these days as “paranoia,” a fear of failure or making a mistake that leads to a state of near paralysis. Innovation and entrepreneurship are all but non-existent in Washington at a time when reinvention and renewal is needed most.

If there’s a bell curve of risk aversion by sector, government and philanthropy are at the far right end (by far). A high-level American diplomat recently described to me the risk aversion in Washington these days as “paranoia,” a fear of failure or making a mistake that leads to a state of near paralysis. Innovation and entrepreneurship are all but non-existent in Washington at a time when reinvention and renewal is needed most.

Yet, hard as it may be to believe given the current state of affairs, a trip to London and Number 10 Downing Street last week has given me renewed optimism that changes may be starting to bubble from the bottom up, in small yet significant ways. The insights come just in time for second-term Obama Administration officials to pay heed.

After all, being President is a thankless and nearly impossible job. While I have been vocal in challenging the Obama Administration to listen and collaborate better, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t these days.

Before turning to the optimistic news, here’s some background about thinking differently about the second-term innovation strategy.

Take government investment in new technology. The history of technology and Silicon Valley is closely linked to government investment and research monies sparking new industries. Hewlett Packard originally relied on government contracts to fund radio frequency technology research, while National Science Foundation grants helped fund Google’s early days.

While the Obama Administration should be applauded for its leadership and courage for investing in renewable energy, the problem with a strategy of making a lot of big bets is that one (really) bad big bet on Solyndra, which received a $535 million loan guarantee from the Department of Energy, became the object of pervasive and prolonged criticism.

Interestingly, the strategy of betting big, rather than small, is one of the signs that corporate innovation researchers Clayton Christensen and Jim Collins have found signals a risk of systemic organizational and financial decline. *(For more detail on these topics and problems, see The Innovators Solution By Christensen and Michael Raynor and How the Mighty Fall by Collins.)

Given the brutal context of national political discourse, it’s of little wonder that I don’t know of more than a handful of very talented people in my generation who have an interest in pursuing roles in government or running for office. I literally don’t know more than 10 people, and I’m fortunate to know many rising GenX and Millennial stars from my research and various experiences. The ones who hold a strong interest for politics and public life seem to be mostly driven by external ideas of who they are, rather than an authentic connection to either themselves or average citizens. That’s certainly different from most (though not all) past American eras, where an ethic of public service ran deep and was honorable.

The institutional problems are deep and systemic. The state of the media, lack of accountability within social institutions, and a well-documented corruption in the plutocracy, all reflections our cultural priorities, surely deserve significant blame. *(For more insight and analysis on these topics, I would recommend That Used to Be Us by Thomas Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum, and It’s Even Worse Than It Looks by congressional scholars Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein.)

Larry, the 10 Downing Street cat, walks on the cabinet table wearing a British Union Jack bow tie ahead of the Downing Street street party, in central London, on April 28, 2011. (Image credit: AFP/Getty Images via @daylife)

Larry, the 10 Downing Street cat, walks on the cabinet table wearing a British Union Jack bow tie ahead of the Downing Street street party, in central London, on April 28, 2011. (Image credit: AFP/Getty Images via @daylife)In what is likely the beginning of a painful triple-dip recession in England, compounded by an era of often ill conceived and poorly executed austerity measures, the middle and lower classes are hanging on by a thread.

Just ask the team at Shelter, a leading UK charity that provides a bevvy of services to keep people in their homes. Decimated by the previous recessions, these families have lost all their savings and are losing their homes in droves. Unlike in Continental Europe, there doesn’t seem to be much of a welfare state remaining in England, the only apparent safety net is a room with four walls. Who helps these people? Shelter, but its budgets are being slashed by austerity measures. Dickens would have a field day.

Just as innovation dries up the farther away decision-makers are from the problems they are trying to solve, and companies struggle when they begin to replace experimental cultures with that made them successful as entrepreneurial ventures with controls, processes, and systems, the problems in England are highly localized.

Senior UK policy makers (who are typically trained as statisticians, policy-makers, lawyers, or economists) often understand the limits of their policy-making ability sitting in Number 10 or nearby. Their hearts are in the right place and they want to solve citizens’ problems in new and innovative ways, yet they need political air cover from the Prime Minister and senior political leaders, as well as support from many other stakeholders to keep their ideas afloat.

Those closest to power in England will tell you that in this era, there’s an enormous need for innovation to come from outside government. Simply put: federal government cannot turn these deep-seeded social and economic problems around alone. What is needed is a new era of openness and collaboration across sectors – social entrepreneurship is truly rising to the fore across both sides of the Atlantic.

Alas, finally it must seem for patient readers, here is where the optimistic part begins. As Tip O’Neil famously put it: “All politics is local.” As problems and funding decisions get pushed down in an era of devolution of power, we’re seeing local councils in England start to innovate and experiment with fresh approaches to solving citizen problems, from the bottom up rather than the top down. We’re seeing that same pattern here in the United States as mayors and governors become the focal points for discovering new ways of administering, funding, and servicing Medicare, Medicaid, and the like.

Akin to the entrepreneurial philosophy of making small bets to discover creative approaches to serving needs, solving problems, and finding opportunities, experimentation has arrived to the federal ranks of England in the form of a black sheep idea: a “Behavioural Insights Team.”

This arm of the UK Cabinet Office, led by the respected academic, thought-leader, and social entrepreneur David Halpern, was established by David Cameron in 2010: “with a remit to find innovative ways of encouraging, enabling and supporting people to make better choices for themselves.”

Winston Churchill in Downing Street giving his famous ‘V’ sign. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Winston Churchill in Downing Street giving his famous ‘V’ sign. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)The unit experiments like mad on everything from how to type tax collection letters in order to maximize participation to how to improve energy efficiency. Halpern and senior policy-making colleagues often reference Nudge by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. Thaler has served as an advisor to the unit and the approach seems to be working, with results that include collecting an extra £200m of income tax and increasing payment rates by 15% after telling late payers in letters that their neighbors had paid their taxes. In addition, they’re finding good results from experiments in getting people into jobs 15-20% sooner in Essex borrowing from insights within US Elections data.

Critics in the press naturally ridicule the team, nicknamed the “nudge unit,” from time to time, yet Halpern’s credibility in influence circles only seems to be growing with the results.

Little things can often lead to large gains. Behavioral economists are developing their thinking and models on this front – what entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurs do in their sleep. It’s not only common sense, as I wrote in Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries, an experimental approach to innovation is the only empirical way to keep innovating as an individual, organization or society.

Although I am no fan of top down austerity, David Cameron earned an important measure of respect from me this week for empowering an arguably quirky approach to solving problems in a new and different way. In such bleak times, he doesn’t have much of a choice, and that’s a good thing. We need a hell of a lot more black sheep like David Halpern working on the side of citizens with experiments if we’re going to begin to restore their faith in federal institutions. I’ll bet that Sir Winston Churchill would be quite proud. Perhaps we Americans can learn from our friends across the Pond. It wouldn’t be the first time.

January 26, 2013

Apple’s Bad Day – HuffPost Live

Apple’s Bad Day

Yesterday was Apple’s worst day in more than 4 years. Apple Inc. stock slid 12.4 percent, leaving it vulnerable to losing its status as the most valuable U.S. company.

Originally aired on January 25, 2013

Hosted by:

Abby Huntsman

GUESTS:

Peter Sims (San Francisco, CA) HuffPost Blogger, Author and Entrepreneur @petersims

Cara Schulz (Minneapolis, MN) Managing Editor at PNC News @Cara_Schulz

Lyletta Robinson (Chicago, IL) ChicagoNow Blogger @WoodlawnWonder

January 21, 2013

Five of Steve Jobs’s Biggest Mistakes

Originally published on Harvard Business Review’s blog .

It’s a great disservice to everyone, especially young people, that the stories that we often hear about the most accomplished entrepreneurs sound so effortless. The truth is just the opposite, even for visionary creative success stories like those of Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Howard Schultz, Wendy Kopp, and even the legendary Steve Jobs. Like any creative process, any entrepreneur who wants to invent, innovate, or create must be willing to be imperfect and make mistakes in order to learn what works and what does not.

It took Dorsey years of experimentation before he finally latched onto what ultimately became Twitter. Wendy Kopp started Teach for America, initially as a conference, on a shoestring budget after graduating from college. And Howard Schultz, while he had great foresight to recognize that Americans needed a communal coffee experience like those that existed in Europe, failed on his first try. As I wrote in Little Bets, when his first store opened in Seattle in 1986, there was non-stop opera music, menus in Italian, and no chairs. As Schultz acknowledges, he and his colleagues had to make “a lot of mistakes” to discover what would become the Starbucks we know today.

Despite what we may have read, Steve Jobs was no different. Here are five of Jobs’s greatest mistakes, all of which history shows he ultimately learned from:

1. Recruiting John Sculley as CEO of Apple. Feeling that he needed an experienced operating and marketing partner, the then 29-year-old Jobs lured Sculley to Apple with the now legendary pitch: “Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life? Or do you want to come with me and change the world?” Sculley took the bait and within two years, Sculley had organized a board campaign to fire Jobs. Jobs himself would surely consider hiring Sculley as a great mistake.

2. Believing that Pixar would be a great hardware company. When Jobs was the last and only buyer standing in 1986 when George Lucas had to sell off the Pixar graphics arm of LucasFilms (for $10 million), he never expected the company to ever make money on animated films. Instead, as Pixar historian David Price shows in his excellent book The Pixar Touch, Jobs believed that Pixar was going to be the next great hardware company. Not even a visionary like Steve Jobs could predict what unfolded at Pixar, yet to his great credit, he supported cofounders Ed Catmull and John Lasseter as they pursued their dream of producing a full-length digitally animated film from day one. He protected their ability to make small bets on short films in order to learn how to eventually make a full-length feature film in Toy Story.

3. Not knowing the right market for NeXT computer. Although Jobs tried to spin NeXT computer as an ultimate success when the assets were sold to Apple in 1986 for $429 million, few in Silicon Valley agreed. The company struggled from the start to find the right markets and customers. If you haven’t seen the video about Jobs describing the vision for NeXT’s customers, you should watch it on YouTube. It’s clear that even Jobs was confused. In it he says, “We’ve had, historically, a very hard time figuring out exactly who our customer was, and I’d like to show you why.”

4. Launching numerous product failures. The Apple Lisa. Macintosh TV. The Apple III. The Powermac g4 cube. Steve Jobs was brilliant about understanding how technology vectors were evolving, yet even he screwed up royally, and often. The lesson that I take from these defunct products is that people will soon forget that you were wrong on a lot of smaller bets, so long as you nail big bets in a major way (in Jobs’s case, the iPod, iPhone, iPad, etc). Jobs was a market research group of one at Apple, which carries with it great risk, yet it should be noted that his batting average improved over time, which comes as no surprise to those who study the benefits of developing strong creative muscles though deliberate practice.

5. Trying to sell Pixar numerous times. By the late 1980s, after owning Pixar for four or five years, Jobs tried on multiple occasions to sell the company, just to break even on his investment, which ultimately equaled roughly $50 million. He shopped Pixar to, among others, Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, and numerous strategic partners and companies. No potential buyer bit. It’s a good thing for Jobs, and his legacy. He eventually engineered the sale of Pixar to Disney for $7.4 billion in 2006.

The lesson, it seems, is fairly simple: Even the great business visionaries and luminaries of our times often fail and have setbacks. Imperfection is a part of any creative process and of life, yet for some reason we live in a culture that has a paralyzing fear of failure, which prevents action and hardens a rigid perfectionism. It’s the single most disempowering state of mind you can have if you’d like to be more creative, inventive, or entrepreneurial. The antidote is to try a small experiment, one where any potential loss is knowable and affordable.

The revolution will be improvised.

January 10, 2013

Fast Company: 30 Second MBA

January 7, 2013

(NPR interview) Obama 2.0: How will the second term play out?

9:06 AM, January 7, 2013

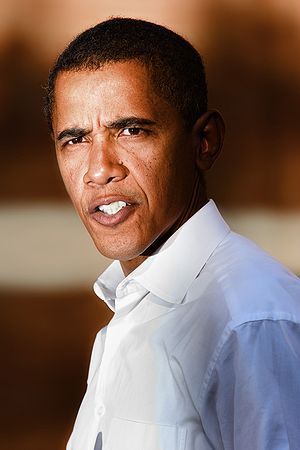

President Barack Obama speaks about the economy at the Daimler Detroit Diesel engine plant Dec. 10, 2012 in Redford, Mich. (Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

Audio

(program audio)

Guests

Julian Zelizer: Professor, Princeton University

Peter Sims: Author of “Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries”

LISTEN

Embed | Help

sponsor:

What kind of president will Barack Obama be in his second term?

Obama has already begun to lay out an agenda for his second term, citing gun control and immigration as two top issues.

Joining The Daily Circuit on Monday, Jan. 7 to discuss Obama 2.0 are Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University, and Peter Sims, author of “Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries.”

READ MORE ABOUT PROSPECTS FOR OBAMA’S SECOND TERM:

Obama’s second chance (Peter Sims on Forbes.com)

Six political lessons of 2012 (Julian Zelizer on CNN.com)

How progress is possible in Obama’s second term (CNN)

President Obama’s 2nd-term history lessons (Politico)

December 21, 2012

Adventures of Harold & Peter (with Baron Davis)

So, last week, Harold O’Neal (the world-class pianist and all around Renaissance man) & I had the very fortunate chance to meet Baron Davis (@baron_davis) of the New York Knicks, and Harold performed for him (which Baron loved!). Baron was an awesome guy, and very down to earth, and creative. Plus, he seemingly quite the BLKSHP ‘sir’ himself from all we gathered, has a great heart and passion for education and social entrepreneurship.

Baron and Harold really inspired me later in the video by talking about their life stories and passion for education. Baron’s nonprofit, Team Play, is all about mentoring and using social media to help unlock youth potential. More soon on that, we hope. THANKS Baron von Davis! BLKSHP UNITE! and, bahh

December 20, 2012

“Perfectionism and imperfection” (from goop; Gwenyth Paltrow’s blog)

From the Entrepreneur

Peter Sims

“Breaking free from perfectionism isn’t easy, largely because of how we’re raised and taught. We’re rewarded and loved by parents, teachers, and mentors for getting good grades, accomplishing athletic achievements, or getting into a great school or job. The problem with that approach to praise and reward is that it builds up our resistance to doing anything that’s less than perfect. And since being imperfect, and being willing to make mistakes in order to discover new paths, opportunities and approaches is essential to any creative process. Unless we’re a genius or prodigy like Mozart, we must unlearn a lot of old habits.

In my experience, many, many people, especially creative people have very judgmental parents. My dad was my harshest critic, though it was all coming from a place of incredible character and unconditional love. His dad did the same, and it just cascaded down. On the flip-side, mothers (and fathers, too) can unleash creativity with their unconditional love and unendingly optimistic encouragement and support, as my mother did (we were very close). Howard Schultz, the CEO of Starbucks, had a similar experience with his parents. Ed Catmull, cofounder of Pixar had the same, as well as his business partner John Lasseter, cofounder and chief creative officer of Pixar, whose mother emphatically encouraged him to follow his childhood interest in cartoons.

“…the key thing that needs to happen is for the person to let go of the feeling that they have to be an idea, rather than just being you…”

Since I work with and lead a lot of artists, the power relationships are very interesting. If a father and/or mother was overly critical, the key thing that needs to happen is for the person to let go of the feeling that they have to be an idea, rather than just being you as I encourage people to be. It’s one of the hardest things to actually do — but what drives it all comes down to support structures and personal will.

For a rich exploration around the negative effects of praising achievements versus effort and why certain people fear failure so much more than others, Stanford Professor of Psychology, Carol Dweck has produced the definitive body of research and book called Mindsets. You can read a great summary article on Dweck’s research in this Stanford Magazine article entitled “The Effort Effect.”

When I jumped off a cliff in my career to try to write a book that eventually became Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries, I was haunted for months by a voice that had no face. It said, ‘You are not worthy…Don’t fail…No one will want to read this crap…You are a fraud!’ Sound familiar?

Dweck’s findings lead to the key insight that anyone, at any age, can become more creative if they’re willing to start trying things. I call these ‘little bets,’ a loss that you determine you can afford to take before making a small bet. The secret to being creative is that everyone who creates anything needs to overcome fears.

“The antidote to these fears is simple. Make a small bet. Do things to learn what to do.”

Maybe a little bet for you is writing a blog piece. Maybe it’s writing a paragraph on a piece of paper. Maybe it’s going to a Pilates class. Maybe it’s calling an old friend. The point is, and as Dweck’s research shows, we can move from a mindset based on fear of failure and perfectionism (what Dweck calls a “fixed mindset”) to a “growth mindset” if we just start taking small steps toward our dreams and goals.

Writer Anne Lamott, (who wrote the gamechanging, Bird by Bird recommends writing what she calls ‘shitty first drafts’ when starting something new. Just get as many thoughts and ideas down on paper as possible, without letting your inner critic take over. Similarly, as Frank Gehry has shared with me, the way he overcomes his fears of failure, is to ‘just start’ making prototypes of his ideas, starting with cardboard and duct tape, crude as they may be at first.

At Pixar, director Brad Bird calls people there who are willing to challenge the status quo and think differently about problems ‘black sheep.’

“Are you a black sheep?”

It starts today. And, it starts small, with a little bet. It’s really that simple and that hard. The world needs your creativity and passion now more than ever. With all the challenges facing our country and world, we need a creative revolution, one driven by the unleashing of millions of previously undiscovered creative talents, talents that will also allow us to be infinitely more human and original.

This revolution will be improvised.”

December 18, 2012

Obama’s Second Chance: Fulfilling the Untapped Potential

Originally appeared on Forbes.

This article is by Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries, coauthor with Bill George of True North, and founder of the BLKSHP.

He must radically change the way he leads. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

He must radically change the way he leads. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)The first time that I believed Barack Obama wanted to be president of the United States was in September 2006, when I saw an interview from Men’s Vogue in which the junior senator from Illinois was asked about his future ambitions, including speculation that he might run for president in 2008.

“My attitude about something like the presidency,” he said, “is that you don’t just want to be president. You want to change the country. You want to make a unique contribution. You want to be a great president.” As the 2008 campaign took shape, he and his team developed an innovative organization and outreach approach that allowed him to become the David who beat Goliath and led many to believe he would be that kind of transformational leader.

But in his first term, he failed to follow though on that promise.

With the punishing and close campaign for his second term now behind him, the president has weathered a brutal first term and many personal and leadership crucibles, and seems to be emerging on the other side of those dark valleys having rediscovered his authentic voice. This transformation is yet to be fully manifested, of course, but in thanking his campaign staff on the night of his re-election, he revealed once again his humanism and the depth of his commitment to the call to public service, dating back to his years as a community organizer working with the disempowered people in Chicago. The Obama who spoke to his staff that night sounded like the Obama who said to Chicago Sun-Times columnist Cathleen Falsani in a 2004 interview :

One of the interesting things about being in public life is there are constantly these pressures being placed on you from different sides. . . . The biggest challenge, I think, is always maintaining your moral compass. Those are the conversations I’m having internally. I’m measuring my actions against that inner voice that for me at least is audible, is active, it tells me where I think I’m on track and where I think I’m off track. . . .

The most powerful political moments for me come when I feel like my actions are aligned with a certain truth. I can feel it. When I’m talking to a group and I’m saying something truthful, I can feel a power that comes out of those statements that is different than when I’m just being glib or clever.

Obama will become a transformational leader by continuing to connect in that way with the values and vision for the future that are important to him personally—the reasons he chose to help disadvantaged and disempowered people as a community organizer rather than taking a lucrative corporate job. That call to service is the life blood of his authenticity and what drew to him such broad and deeply impassioned support in the 2008 campaign. As John W. Gardner, the founder of Common Cause and the White House Fellows program and secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in the Johnson administration once said, “The world loves talent but pays off in character,” and character remains the fundamental basis for Barack Obama’s potential to be a leader of Lincolnesque proportions.

Yet character alone will not be enough. In this intensely partisan era, in which we are facing so many intensely complex challenges—ranging from global warming to pension and tax reform to the necessity of deleveraging debt burdens at the government, organization, and personal level—the country desperately needs renewal and reinvention, not only of our physical infrastructure, but also of our social infrastructure and our systems of governing. Tax reform is an obvious example, one that every serious observer and participant in American business and politics agrees must be addressed. As during the transformational presidencies of the past, those of Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, and Reagan, the American people today crave the right message of healing, empowerment, and progress, and the leadership to follow through on that message.

That type of leadership cannot and will not come from the top down in Washington or the Northeast corridor. It must come from the bottom up, and any type of bottom-up innovation must begin with the leadership having an understanding of underlying and quite often unarticulated citizen needs and desires. Every major progressive social change movement in U.S. history, from abolitionism to women’s voting rights to civil rights to gay rights, began with small groups of American citizens, thinkers, writers, and grassroots leaders determined to realize social change. Great presidents merely do their best to influence those directions, or, more realistically, to align their own authentic goals with the larger cultural trends.

Ronald Reagan may have said and done all the right things to help shift Southern blue to red on the electoral map, but that transformation began decades earlier when Lyndon Johnson extended the hand of presidential affirmation toward Martin Luther King, Jr., in support of the Civil Rights Act. As longtime presidential adviser David Gergen has often argued, one of Reagan’s great advantages in preparation for becoming president was to have crisscrossed the country for years as a TV spokesman for General Electric during the 1950s and 1960s, meeting more than 250,000 American citizens. In Howard Gardner’s “multiple intelligence” terminology, Gergen describes Reagan’s signature gift as interpersonal skill. He knew the American people extremely well and was able to align himself and his story with the public sentiment to craft the right message for the times.

If President Obama can capture and connect with the public’s urgent desire today for creative problem solving, crafting the right vision, message, and, most important, approach to governing, he will have his shot at greatness. But in order to do so, and to lead in a truly transformational way, he and his team must create a much different culture in the White House during the second administration—one that is more outward facing than inward facing, one that treats the White House as a platform for amplifying and collaborating with the public, with companies, causes, and groups across sectors—in order to govern from both the top down and also the bottom up. All the major drivers of influence, from the media to publishing and thought leadership channels to academia and to popular culture, are no longer managed and driven by a small handful of gatekeepers and opinion leaders. Social media technologies have democratized and distributed influence and power, so that we’re all now part of various tribes—our extended families, our workplace and school networks, and our “friend” circles. The democratization and distribution of power means both that no president is likely to be able to harness the kind of widespread public support needed to tackle today’s “wicked problems” if he doesn’t listen to those tribes and work with them in developing solutions. In order to be a transformational leader, President Obama must tap into the wisdom of the crowd. He must make the White House a platform for convening and building ecosystems for solving problems in new ways. This new style of governing is urgent because of both the nature of the problems we face and the deeply divided nature of the country.

The presidential campaign felt like a modern day Civil War. It displayed the worst of the country’s ideological extremism—racial bigotry, religious intolerance, and competing libertarian versus communitarian economic worldviews. It also highlighted the insidious role of money in the political system. Tom Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum argue persuasively in their 2011 book That Used to Be Us that money has corrupted America’s political parties and institutions to the point of near moral bankruptcy.

It is a very sad statement about the political system that someone must pay anywhere from $2,000 to $38,500 to meet the president, or any elected leader, for that matter. Given the short-term incentives to cater to donors’ desires, our politicians are increasingly required to spend disproportionate amounts of their time raising money rather than working on problem solving. This has made the government much too reactive. Poll-tested and cynical incrementalism has replaced visionary leadership. Virtually no one—from my Uncle Joe, who’s a truck driver, to John Huntsman, Sr., the highly respected executive and wealthy philanthropist who helped bankroll his son’s campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 2011 but told The New York Times in October 2011 that the political system is broken—no one feels represented or heard anymore.

You don’t need to read Tom Friedman to understand the core problem. My Uncle Joe reads the local newspaper at best and says it better than Friedman could: “We’ve forgotten who is the boss in this country. The citizens are the boss!”

Meanwhile, the problems we’re facing are ever more difficult. We’re a nation beleaguered by war yet still rightfully fearful of very real threats and instabilities abroad. The Army has faced a comeuppance in the Middle East, where the arrogant and ignorant strategies of politicized generals, most notably Tommy Franks, gave way to the realities on the ground. Ret. Col. Casey Haskins, the former director of military instruction at West Point, after serving as the chief of strategic plans for Multi-National Force—Iraq, puts it, “Not only can we not teach doctrinally approved solutions any more [which take roughly two years to be approved], the truth is, we don’t even know all the problems!”

Reforming Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, confronting global warming honestly, and reforming the tax system are urgent priorities that got virtually no attention in the presidential campaign, save small tidbits in the presidential debates.

On top of that we face extreme levels of inequality not seen since the Gilded Age, and many workers just don’t have the skills needed to compete in today’s hypercompetitive globalized economy.

These are the types of problems that no president, even with the best senior team and staff in the world, can solve alone. That’s why it’s so important that President Obama now correct for the errors in his first term and come through with the innovative, open, engaged, and progressive style of governing he initially promised.

In 2008 the electorate flocked to Obama largely because of his message that he would govern in a new way, and because his campaign team did in fact create a new kind of campaign built on a larger base of supporters and smaller contributions, and so on. But then, for a variety of good reasons and some unknown ones, the president abandoned that approach as soon as he took office. He and his closest advisers failed to stay connected with supporters, even the most ardent ones, their potential champions, education partners, and eyes and ears on the ground all around the country. Around this time in 2008, someone in the transition team decided not to shift the campaign’s new media team, even though it could have kept it in place as a not-for-profit in order to maintain the network of grassroots support and two-way communication, which it had managed to do so effectively during the campaign. Instead most of that group was turned over to the Democratic National Committee, with a few members led by Macon Phillips taking jobs in the White House. That was a mistake.

Yes, of course the transition team had to focus on managing the worst economic crisis in recent history. Time was of the essence. But time is always of the essence for high-performing organizations, and that doesn’t mean that the solution set of policy options could not have been expanded. Greater engagement with the business community would only have enhanced the stature of and external support for the economic team. Instead, the team suffered from a style that resembled “the smartest guy in the room” syndrome, a common failing of insecure CEOs and managers who are often driven by a culture of fear and arrogance rather than a culture of inclusiveness, authenticity, and empowerment. They bought into a false tradeoff between the need to deal with the crisis and the power of engaging people to develop a longer-term strategy for governing differently; those should not have been mutually exclusive options. That insular style of economic management and policy making was the greatest leadership failing of the President’s first term.

Obama had at his disposal an army of extremely talented, respected, and influential people who were eager to be involved in his historic administration, whether formally or informally; they were just waiting to be asked, and to be led. I saw this first-hand. I was one of 15 members of the Business Leaders for Obama team, a group chaired by Gary Gensler, who went onto become the chairman of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and which included Julius Genachowski, who would head the Federal Communications Commission, Alec Ross, now senior adviser for innovation to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and private equity investors including Steve Rattner, Robert Altman, and Mark Gallogly.

We were tasked during the campaign with leading outreach to the business community, gathering endorsements, and providing policy position feedback. I was asked because of my experience as a management writer as coauthor of True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership, with Bill George, former chief executive of Medtronic and now a professor of management at Harvard Business School, as well as my previous work in venture capital with Summit Partners.

After the election, because I had come to know so many people who went on to jobs on the transition team in mid to late November 2008, I had a number of conversations with members of the team encouraging them about how the administration might be able to leverage the grassroots elements of the campaign into a different way of governing. The driving question was: How do we stay truly connected with all of these citizens around the country to create feedback and educational and campaign mechanisms, in order to govern differently? Why, for instance, didn’t impassioned retired teachers in Napa, California, who had been such great local champions during the campaign, continue to play a role? One person I spoke with about this on several occasions was Joe Rospars, who had led the Obama ’08 new media team and thought it was a good idea.

But in a short time that army of foot soldiers, from those retired teachers to the Silicon Valley coalition of green energy leaders for Obama and the several hundred CEOs who had offered the president their personal endorsements, lost their connection to the Obama team, and as a result lost their sense of connection to the larger cause we had believed in, as well as our feeling of empowerment and shared purpose.

If I were to list the names and titles of people who discussed with me their common dismay at this turn of events, it would read like a Who’s Who of Silicon Valley and the power networks of the Northeast corridor.

The good news is that now Obama has a second chance. If there’s one thing the president has surely learned in his first term, it is that he cannot do it all on his own. The president and his team have a tailwind of victory behind them now like the one they came into office with, and they have a window of time to get a team in place to engage with these broader champions and networks and to reconnect to larger causes that are so vital to this constituency, ranging from the desire to help reinvent the economy and job creation programs to education reform and bridging the skills gap and addressing urgent environmental concerns. And the good news is that the president’s senior advisers seem interested in making this change. White House Chief Technology Officer Todd Park has, for example, been on a roadshow of sorts all fall, going around the country with Steve Case and a band of chief executives, technologists, and opinion leaders sharing sketches for new ways of leading, yet also, more important, listening.

Obama is also well suited for the new more open governing style. Fortunately, the president’s greatest assets in taking advantage of the possibilities of this networked and transparent world are the same things that brought him such impassioned support in 2008: his integrity, character, and authenticity and also his desire to be innovative. If there’s one thing that Jon Stewart, Steven Colbert, and the army of supporters he needs to rally can smell out quickly, it is a lack of authenticity. Just ask Mitt Romney. And there’s nothing more powerful in an open and transparent world than authenticity.

The biggest question now is whether the president and his team can truly listen. I’m not talking about analyzing reams of polling data. They’re clearly very good at that. I’m talking about being able to act like an anthropologist, to get what Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus who is both an economics professor and a leading social entrepreneur, calls getting out of the office to get “the worm’s eye view” about social problems that are new and complex before using an experimental and entrepreneurial approach to solving them. The president can learn more about what’s really going on in the country by watching The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, and by monitoring trends on Twitter and Facebook every night before he goes to bed, than he can by listening to a small circle of advisers who couldn’t possibly cover as much ground.

The great news is that the administration can lock arms in collaboration with a sea of social ventures, led by social entrepreneurs who are united around common values and purpose. The American people from Detroit to Louisville to the rural areas of Northern California have been reinventing and renewing all through the punishment of the financial crisis. The artists, entrepreneurs, and inventors so core to America’s promise and founding ideals are resilient and inspired. What America needs from its president is to be acknowledged and affirmed for reinventing their own lives, companies, and communities. The solution to America’s ills lies not in the swamp of Washington but in the fields, startups, and small businesses, classrooms, and social entrepreneurs of America.

Obama must listen to and engage with people like Judith Jackson, who leads Youthville Detroit. A deeply humble and authentic leader, Jackson would be the last person to toot her own horn, yet she serves more than 500 Detroit youths a day in a variety of after-school and creative education programs. And if you ask Judith about what she needs, the topic of funding inevitably comes up soon. Raising money is a big part of her job. With the decline of earmarks, Jackson must build out her own ecosystem of supporters and funders, including nice gifts from the likes of singer-songwriter Usher’s foundation. The White House could help Jackson enormously merely by shining a light on stories such as hers, and show how Jackson’s story shares much in common with that of the students at Oral Roberts University who are deeply passionate about using social entrepreneurship to achieve social justice ends, including to combat meth addictions in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Because we don’t even know the problems, let alone all the solutions for reinventing and renewing America, everyone must be a social entrepreneur. Programs like Fuse Corps, Code for America, and StartUp America are helping to provide the catalysts and energy to focus on entrepreneurial approaches to big problems from the bottom up, including by helping to build the all important ecosystems that support and maintain innovation. That bottom-up approach to change must begin with a deep awareness and empathy for citizens’ problems and needs, something that all too often gets lost in top down decision-making processes.

Those 35 and under in America are extremely entrepreneurial. They have to be—they must invent and reinvent their careers multiple times in just their first few years out of college, and all while managing to repay educational debts. They are well schooled in the prerequisites for invention—tinkering, play, rapid iteration, and resilience through failure.

What America needs now is a Renaissance of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. President Obama may just be able to ignite that flourishing if he makes a sincere effort to tap into the spirit of American community and collaboration that I’ve seen all around the country. He can lead Americans of all races, religions, and persuasions, from students at Oral Roberts University to urban artists and musicians from the other side of the tracks in Detroit, in locking arms and marching together in a shared desire to solve our pressing problems in new and creative ways.

This revolution will be improvised.

This article is available online at:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesleadershipforum/2012/12/14/obamas-second-chance-fulfilling-the-untapped-potential/

December 14, 2012

Adventures of Harold & Peter with Baron Davis (preview)

So, yesterday, Harold O’Neal (the world-class jazz composer and pianist) & I had the very fortunate chance to meet Baron Davis (@baron_davis) of the New York Knicks, and Harold performed for him (which Baron loved!). Baron was an awesome guy, and very down to earth, and creative. Plus, he seemingly quite the BLKSHP ‘sir’ himself from all we gathered, has a great heart and passion for education and social entrepreneurship. We’re still trying to get the full video off of my iPhone (big file!  , so here’s just a sample here. Baron and Harold really inspired me later in the video by talking about their life stories and passion for education. More as soon as we get a bit of tech help (btw, if you’re really good with technology and WordPress, Harold and I are looking for an intern to help us techno-idiots [speaking for myself here] to work with WordPress and YouTube). THANKS! BLKSHP UNITE! and, bahh

, so here’s just a sample here. Baron and Harold really inspired me later in the video by talking about their life stories and passion for education. More as soon as we get a bit of tech help (btw, if you’re really good with technology and WordPress, Harold and I are looking for an intern to help us techno-idiots [speaking for myself here] to work with WordPress and YouTube). THANKS! BLKSHP UNITE! and, bahh

Peter Sims's Blog

- Peter Sims's profile

- 21 followers