Marc Weidenbaum's Blog, page 387

February 20, 2015

via instagram.com/dsqt

Local rail symbol to ring bell when approaching station. #soundstudies #ui #ux

Cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.

February 19, 2015

Disquiet Junto Project 0164: Junto Hay Fat Choy

Each Thursday in the Disquiet Junto group on SoundCloud.com and at Disquiet.com, a new compositional challenge is set before the group’s members, who then have just over four days to upload a track in response to the assignment. Membership in the Junto is open: just join and participate.

This assignment was made in the late evening, California time, on Thursday, February 19, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, February 23, 2015.

These are the instructions that went out to the group’s email list (at tinyletter.com/disquiet-junto):

Disquiet Junto Project 0164: Junto Hay Fat Choy

The Assignment: Create music that emerges from the sound of fireworks.

These are the steps for this week’s project:

Step 1: Locate or create a field recording of fireworks (at freesound.org, for example)

Step 2: Listen to the musical content of the recording — rhythm, tempo, tone, arc, melody.

Step 3: Create a piece of music that begins as five seconds of that field recording, and then emerges out of the sound of fireworks.

Step 4: Upload the finished track to the Disquiet Junto group on SoundCloud.

Step 5: Be sure to include link/mentions regarding the source tracks.

Step 6: Then listen to and comment on tracks uploaded by your fellow Disquiet Junto participants.

Deadline: This assignment was made in the late evening, California time, on Thursday, February 19, 2015, with a deadline of 11:59pm wherever you are on Monday, February 23, 2015.

Length: The length of your finished work should be one minute.

Upload: Please when posting your track on SoundCloud, only upload one track for this assignment, and include a description of your process in planning, composing, and recording it. This description is an essential element of the communicative process inherent in the Disquiet Junto. Photos, video, and lists of equipment are always appreciated.

Title/Tag: When adding your track to the Disquiet Junto group on Soundcloud.com, please include the term “disquiet0164-juntofireworks” in the title of your track, and as a tag for your track.

Download: It is preferable that your track is set as downloadable, and that it allows for attributed remixing (i.e., a Creative Commons license permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution).

Linking: When posting the track, please be sure to include this information:

More on this 164th Disquiet Junto project — “Create music that emerges from the sound of fireworks” — at:

http://disquiet.com/2015/02/19/disqui...

More on the Disquiet Junto at:

Join the Disquiet Junto at:

http://soundcloud.com/groups/disquiet...

Disquiet Junto general discussion takes place at:

Image associated with this project by Carl Guderian, used via Creative Commons license:

via instagram.com/dsqt

Listening/looking up. At final event for Junto installation at SJ Museum of Art.

Cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.

via instagram.com/dsqt

February 18, 2015

Tokyo Beat Playlist

After two days running posts of elegant beats by Tokyo-based Hideyuki Kuromiya, I corresponded with him, and asked if he might put together a playlist of his beats, so they’re all in one place and easy to follow. He graciously did just that, and he added a new beat for today, “hb24,” in which the vocal sample is more evident than in the prior two. That vocal is a bit of moaning melisma that is crunched between sandpaper percussion, vinyl-skip plosives, and a sharp short-circuit shock. I’m covering these three days in a row because while I occasionally report on regular woodshedding projects by folks like Madeleine Cocolas, Taylor Deupree, and Marcus Fischer, featuring such work in an immediate sequence does a better job of making an impression of the effort involved, which in Kuromiya’s case is daily.

Set of beats originally posted at soundcloud.com/kuromiya-hideyuki. More from Kuromiya, who is based in Tokyo, Japan, at twitter.com/hideyukitchen.

February 17, 2015

More Tokyo Beats

Another day, another beat from Tokyo-based Hideyuki Kuromiya. I mentioned here a beat by him yesterday, and to emphasize the studiousness inherent in his beat-a-day practice, I was glad today’s was as strong as yesterday’s. This time the pace feels even slower, more willfully plodding, the downtempo affect the result of an off-kilter plosive that feels like a heavy heel dragged rather than just set down on pavement. Sour keyboard notes and what sounds like a saxophone sample melting in thin air intersect in interesting ways. While yesterday’s track was a series of concise, self-contained instances, this is a much more layered and complex undertaking. Play it on repeat.

Track originally posted for free download at soundcloud.com/kuromiya-hideyuki. More from Kuromiya, who is based in Tokyo, Japan, at twitter.com/hideyukitchen.

Sound Class, Week 3 of 15: Sound Design as Score

Quick question: How many microphones are in the room you are in right now?

That’s the fun and instructive little parlor game I like to play with my students a few weeks into the sound course I teach. They each share their guess with me, and then I talk through all the technology in the room, and rarely is anyone even close to the right number. The students are often a little surprised, at first, to learn that many of their phones have three microphones, and that the most recent MacBook Air laptops have two microphones, to allow for noise cancellation of ambient sound from the environment. They forget that many of their earbuds come with microphones, as do their iPads, their iPods, their Bluetooth headpieces. We’re meeting in a classroom, so there’s no concern about their game consoles, or their smart thermostats, or their home-security system. By the end of the exercise, they are a little anxious, which is productive because this week we discuss Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece thriller, The Conversation. By the end of the exercise, we’re all a bit like Gene Hackman at the end of the film: wondering where the surveillance is hidden.

There is almost every week of the class a question at its heart to which I do not have an answer. The question this week is: How is the increasing ubiquity of recording equipment in everyday life transforming the role of sound in film and television?

This is third week of the course I teach at the Academy of Art on the role of sound in the media landscape. The third week marks the close of the first of three arcs that comprise the course. First come three weeks of “Listening to Media,” then seven weeks of “Sounds of Brands,” and then five weeks of “Brands of Sounds.” If the first week of the course is about the overall syllabus and the second week looks back on 150,000 years of human history, how hearing has developed biologically, culturally, and technologically, then the third week focuses on just barely 100 years: We look at how film and, later, television have shaped the way sound is employed creatively.

Each week my plan is to summarize the previous class session here. Please keep in mind that three hours of lecture and discussion is roughly 25,000 words; this summary is just an outline, maybe 10 percent of what occurs in class.

As with last week’s “Brief History of Listening,” this week uses a timeline as the spine of the discussion, or in this case a “trajectory.” For most of this class meeting, this “trajectory” appears on the screen at the head of the room:

•• A Brief Trajectory of Film Sound

• filmed theater

• moving camera / editing

• synchronized sound (1927, Jazz Singer)

• talkie → term “silent film” (c.f. “acoustic guitar”)

• orchestral score (classical tradition)

• electronic (tech, culture, economics)

• underscore (Cliff Martinez, Lisa Gerrard, Clint Mansell, David Holmes, Underworld, Nathan Larson)

• sound design as score

• side note: score as entertainment (audio-games, sound toys, apps)

I’ll now, as concisely as possible, run through what we discuss for each of those items.

•• A Brief Trajectory of Film Sound

• filmed theater

We begin at the beginning of film, and discuss how when new media arise they often initially mimic previous media, in this case showing how early film was often filmed theater.

• moving camera / editing

In time the combination of moving cameras and editing provide film with a visual vocabulary of narrative tools that distinguish it from filmed theater.

• synchronized sound (1927, Jazz Singer)

We talk about how the introduction of sound to film doesn’t coincide with the introduction of recorded sound. The issue isn’t recording sound. It is the complexity of synchronization.

• talkie → term “silent film” (c.f. “acoustic guitar”)

The word “retronym” is useful here. A retronym is a specific type of neologism. A “neologism” is a newly coined word. A retronym is a new word for an old thing required when a new thing arises that puts the old thing in new light. The applicable joke goes as follows:

Q: What was an acoustic guitar called before the arrival of the electric guitar?

A: A guitar.

We also discuss the brief life of the term “cameraphone,” which was useful before cameras became so ubiquitous that a consumer no longer makes a decision about whether or not to buy a phone with a camera. Given the rise of social photography, it’s arguable that cellphones are really cameras that also have other capabilities.

In any case, that tentative sense of technological mid-transition is at the heart of this part of the discussion, about how films with sound were initially as distinct as phones with cameras, and how in time the idea of a movie without sound became the isolated, unusual event. We talk about how the “silent” nature of “silent film” is a fairly popular misunderstanding, and that silent films in their heyday were anything but, from the noise of the projectors, to the rowdiness of the crowds, to the musical accompaniment (often piano).

• orchestral score (classical tradition)

We discuss how the orchestral nature of film scores was not unlike the way films originated in large part as filmed theater. The orchestral score connected the audience experience to mass entertainments, like theater and and opera and musicals, in which orchestras and chamber ensembles were the norm. Long after the notion of filmed theater had been supplanted by a narrative culture unique to film, the norm of the orchestral score lingered.

• electronic (tech, culture, economics)

We discuss the rise of the electronic score, how the transition from orchestral to electronic involved a lot of difference forces. Technology had to become accessible, and changes in pop culture eventually required music that no longer felt outdated to couples out on a date, and finally economics meant that large Hollywood studios, which often had their own orchestras and production procedures, needed incentives to try something new.

• underscore (Cliff Martinez, Lisa Gerrard, Clint Mansell, David Holmes, Underworld, Nathan Larson)

The broad-strokes sequence of how movie scores changed since the rise of the talkie has three stages, from traditional orchestral scores, to early electronic scores that mimic orchestral scoring, to electronic scores that have their own unique vocabularies. (That’s leaving aside groundbreaking but also way-ahead-of-their-time efforts such as Bebe and Louis Barron’s Forbidden Planet.) I highlight the work of a handful of composers, all of whom to varying degrees employ what can be called “underscoring”: scores that rarely reach the crescendos of old-school melodramatic orchestral scores, and that often meld with the overall sound design of the filmed narrative they are part of. (I also note that all of these folks came out of semi-popular music: Cliff Martinez played with the Dickies, Captain Beefheart, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Lisa Gerrard with Dead Can Dance, Clint Mansell with Pop Will Eat Itself, and Nathan Larson with Shudder to Think. Underworld is a band, and David Holmes is a DJ and solo electronic musician.)

• sound design as score

Where I’ve been heading with this “trajectory” discussion — I call it a trajectory rather than a “timeline” because I feel the sense of momentum in this particular topic — is to focus on contemporary work in which sound design is the score. To emphasize the transition, I show a series of short videos. We watch the opening few minutes of a 1951 episode of Dragnet and then the opening portion of an episode of Southland, which closely follows the model of Dragnet: the martial score, the civic-minded officer’s point of view, the spoken introduction, the emphasis on “real” stories. The difference is that the melodramatic score of Dragnet is dispensed with in Southland, as is the notion of a score at all. Southland, which aired from 2009 through 2013, has no music once its filmic opening credits were over. Well, it’s not that there’s no music in Southland. It’s that any music one hears appears on screen, bleeding from a passing car, playing on the stereo in a doctor’s office, serving as the ringtone on someone’s cellphone. All sound in the show collectively serves the role once reserved largely for score. When there’s a thud, or a gunshot, or a droning machine, it touches on the psychology of the given scene’s protagonist.

To make my point about the means in which sound design serves as a score, I play an early clip from I Love Lucy, and contrast the early employment of laugh tracks in that show with portions of MAS*H, another sitcom, that lacked laugh tracks. I talk about the extent to which much movie scoring is often little more than a laugh track for additional emotions.

We then spend about 15 or 20 minutes watching over and over the same very brief sequence from David Fincher’s version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, which I dissect for the gray zone between where the movie’s sound ends and the score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross begins. (If I have time in the next few weeks, I may do a standalone post with screenshots and/or video snippets that break down the sequence.)

In the work of Fincher, Reznor, and Ross we have a masterpiece of underscoring. The film isn’t quite in Southland‘s territory, but it is closing in on it. I then show two videos that work well together. These are promotional interviews, mini-documentaries, one of Jeff Rona talking about his work on the submarine movie Phantom and the other of Robert Duncan talking about his work on the submarine TV series Last Resort. The videos are strikingly similar, in that both show Rona and Duncan separately going into submarines, turning off the HVAC, and banging on things to get source audio for their respective efforts. All the better for comparison’s sake, the end results are quite different, with Duncan pursuing something closer to a classic orchestral sound, and Rona in a Fourth World vibe, more electronic, more pan-cultural, more textured. What is key is that the sounds of the scores then lend a sense of space, of real acoustic space, to the narratives whose actions they accompany.

Some semesters I also play segments from The Firm, to show the rare instance of a full-length, big-budget Hollywood film that has only a piano for a score, and Enemy of the State, to show references to The Conversation, and an interview with composer Nathan Larson, who like Rona and Duncan speaks quite helpfully about using real-world sounds in his scoring.

In advance of the class meeting, the students watch Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 masterpiece, The Conversation. This is a core work in sound studies, thanks to both Walter Murch’s sound design in the film, and to the role of sound in the narrative. Gene Hackman plays a creative and sensitive private eye, who uses multiple microphones to capture an illicit conversation. Sorting out what is said on that tape causes his undoing. It’s helpful that the building where I teach my class is just a few blocks from Union Square, where the opening scene of the film is shot. We discuss Walter Murch and his concept of “worldizing,” of having sound in the film match the quality experience by the characters in the film. For class they read a conversation between Murch and Michael Jarrett, a professor at Penn State, York. They also are required to choose three characters other than Gene Hackman’s, and talk about the way sound plays a role in the character development. After the discussion, we listen in class to a short segment from Coppola’s The Godfather, released two years before The Conversation, in which Al Pacino kills for the first time, and discuss how there is no score for the entire sequence, just the sound of a nearby train that gets louder and louder — not because it is getting closer, but because its sound has come to represent the tension in the room, the blood in Pacino’s ears, the racing of his heart. This isn’t mere representation. It is a psychological equivalent of Murch’s worldizing, in which the everyday sounds take on meaning to a character because of the character’s state of mind. Great acoustics put an audience in a scene. Great sound design puts an audience in a character’s head.

The students also do some self-surveillance in advance of the class meeting. The exercise works well enough on its own, but it’s especially productive when done in parallel with The Conversation, which at its heart is ambivalent at best about the ability of technology to yield truth. The exercise, which I listed in full in last week’s class summary here, has them take a half-hour bus trip, and then compare what they recall from the trip versus the sound they record of the trip: what sounds do they miss, what sounds do they imagine.

When there is time, I like to close the trajectory/timeline with “score as entertainment (audio-games, sound toys, apps),” and extend the learnings from film and television into other areas, like video games, but there was not enough time this class meeting.

• Homework

For the following week’s homework, there are three assignments. In their sound journals students are to dedicate at least one entry to jingles (the subject of the following week’s class) and one to the sound in film or television. They are to watch an assigned episode of Southland and detail the role of sound in the episode’s narrative, the way sound design serves as score. And they are to locate one song that has been used multiple times in different TV commercials and discuss how it means different things in different contexts.

Note: I’ve tried to do these week-by-week updates of the course in the past, and I’m hopeful this time I’ll make it through all 15 weeks. Part of what held me up in the past was adding videos and documents, so this time I’m going to likely bypass that.

This first appeared in the February 17, 2015, edition of the free Disquiet email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.

This Week in Sound: Tasting Sound, Muting the Browser, …

Film Noise: There’s an interesting debate within the Academy Awards. I care very little about horse races, but this gets at the very nature of film sound. As Brice Ezell summarizes at Pop Matters, films that have prominent music other than the score aren’t eligible for best-score awards, which is a peculiar disincentive in cases like Clint Mansell’s work on Black Swan, which was disqualified because of the prominence of the music from the ballet that is the subject of the film. The concern this award season is, apparently, Antonio Sanchez’s music for Birdman.

http://www.popmatters.com/column/190160-a-call-for-the-academy-to-reconceptualize-the-best-original-score-ca/

Tasting Sound: Jo Burzynska’s essay isn’t about synesthesia per se, but it is about the intermingling of senses. In “Wine and Music: Synergies Between Sound and Taste,” presented last year at the International Food Design Conference and Symposium in New Zealand, and just uploaded to academia.edu, Burzynska outlines scientific research currently employed in connecting the role of sound to the appreciation of wine specifically, and food more generally. The key phrase is “crossmodal correspondence.” There are many footnotes, and I’m just beginning to dig into them all.

https://www.academia.edu/10715994/Wineandsound

Muting the Browser: There’s an experimental but easy to access tool within the Chrome browser that lets you mute any tab. I found it easy to turn on, but I had to reboot my computer before it took effect. Google recently added a tool to Chrome that shows a speaker on any tab that is emitting sound. Now you hover your cursor/mouse over the speaker and can click on it to turn mute it.

http://fieldguide.gizmodo.com/mute-noisy-tabs-in-google-chrome-1683215637

Collecting Bertoia: The label Important Records is doing a Kickstarter to raise $15,000 to purchase equipment to allow for the conservation of Harry Bertoia’s Sonambient (sound sculpture) tape reels, and to release previously unheard works. (Found thanks to Bruce Levenstein / Compact Robot.)

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1983757235/help-archive-harry-bertoias-complete-sonambient-re

Acoustic Space: The big-news design article in the current New Yorker issue is the interview with Apple’s Jonathan Ive, but there’s also a detailed sound-design story by Alex Ross about how technology is improving the acoustics of restaurants and concert halls:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/23/wizards-sound

This first appeared in the February 17, 2015, edition of the free Disquiet email newsletter: tinyletter.com/disquiet.

Writing About Writing About Music

The single person I most wish I’d had a chance to interview but didn’t is the late Dennis Potter, best known for his work on Pennies from Heaven and The Singing Detective. His use of music in his screenplays really registered with me, about the way music shapes people’s emotions, their interactions, their sense of the world, about how music works in people’s minds, how it becomes part of their thought processes. But I’m kind of glad I didn’t interview him when he was alive, because I would have mucked it up. I wasn’t ready.

That statement is the answer to an inquiry I received from the editors of a new book about writing about music. The book is titled How to Write About Music: Excerpts from the 33 1/3 Series, Magazines, Books and Blogs with Advice from Industry-leading Writers. It’s co-edited by Ally-Jane Grossan of 33 1/3, which published my book about Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume II, and by Marc Woodworth, a lecturer in the English department at Skidmore College and associate editor at Salmagundi Magazine.

That statement is the answer to an inquiry I received from the editors of a new book about writing about music. The book is titled How to Write About Music: Excerpts from the 33 1/3 Series, Magazines, Books and Blogs with Advice from Industry-leading Writers. It’s co-edited by Ally-Jane Grossan of 33 1/3, which published my book about Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume II, and by Marc Woodworth, a lecturer in the English department at Skidmore College and associate editor at Salmagundi Magazine.

My comments about Dennis Potter, and other subjects, appear in their book. The two other questions to which my answers appear in the book involve “the biggest mistake you’ve ever made in your career” and whether you can drink while reviewing a concert.

I thought I’d share some of the other things I wrote in response to Grossan and Woodworth’s inquiry, all on the subject of writing about music:

Q: Describe in detail the process of writing your most recent piece (whether profile, review, etc.). Do you have a specific workflow for your music writing?

A: I interviewed a musician. The editor at a publication for which I write on occasion emailed me with the pitch — well, reverse pitch — saying he guessed I’d find this musician’s work of interest, and the editor was right. The interviewee was someone I’d long intended to speak with, and I had just never got around to it. I re-listened to all his music, and took notes on key tracks, not just the recent releases, but early material that had really resonated with me. I read up on recent interviews, and spent time observing the musician’s various social networks. The conversation, a phone call, went very well. I quickly and cursorily transcribed the whole thing and found the pertinent material, stuff that I thought would be most of interest. Those sections I went back and transcribed in detail, trying to capture the nuances of his speech patterns. While doing this, I formulated an opening and closing to the article, and from there I pieced together an outline, a structure. Then I connected the portions, threading in the interview segments, and then I reworked the text for several successive drafts so that the whole thing read smoothly. This article had to be turned around very quickly, because it was a late-in-the-game assignment, and it was timed to coincide with a preview of an upcoming local concert performance. One thing I kept in mind was that the publication was a general-interest one, so I made sure that the opening was not too insidery, and that there were easy ways for the reader to extrapolate ideas and experiences from what was covered, even if the subject was unfamiliar to them. That’s pretty much how I handle all my freelance writing — if it isn’t interview-based, then replace the interview part with research. If I’d had more time I would have done secondary interviews, with the musician’s associates. Also, I do a lot of writing on my own website, which I’ve had since 1996, and that writing is a little less structured. The pieces are generally written more linearly, with less immediate concern for structure.

Q: Do you need to know how to make music to write about it?

A: Certainly not. It doesn’t hurt, and there’s lots of great writing about music by people who make it, but there’s also lots of writing about music by people who make it that, well, isn’t so engaging or informative. That said, ignorance is not a useful perspective. If you don’t know how to make music, you still have to have something to say.

Q: If there was one thing you could change (besides the money thing) about music writing, what would it be?

A: This response may not be useful, but it’s the best I could do: I’m not clear that there is a specific thing called “music writing” that one could change. To the extent that I understand what we mean by “music writing,” I guess the main thing I’d suggest is people write outside of what is considered “music writing.” There’s nothing particularly wrong with “music writing” but there’s a big world out there, much larger than “music writing.”

Q: Once you are assigned an interview subject, how do you go about formulating questions to ask them?

A: Fortunately, it usually works the other way around for me. There’s a musician I’m interested in, and questions already exist that I want to ask them. No matter the subject, I’m cautious about asking questions they’ve been asked before, and I read up on recent interviews. If I need to cover well-trodden ground, I acknowledge that, and rather than re-ask a previously asked question, I’ll bring up the previous answer and make a question of that — for example, “When you said [X] in 2003, what did you mean by [some specific detail]?” I pretty much never ask anything personal, unless it relates directly to the musicians’ work, and even then it’s not really my beat, as it were. The whole cult of personality, the gossip, the intrigue of feuds and dalliances — that holds no interest for me. I think my disinterest has served me well in having musicians open up to me about their creative endeavors. I probably over-prepare when interviewing musicians. Questions aren’t difficult for me, because I’m always full of questions. You know how little kids as lots of questions? I never outgrew that. The hard part is formulating the questions so they’re easily communicated, and sequencing them so the conversation flows well.

Q: How would you suggest that a young writer meet and contact editors or industry figures?

A: If you can’t reach them, find someone else to talk to. Life’s short. No one is that important. Just write, and publish your own stuff if you have to. If you have something to say, people will find you.

Q: Describe your first successful pitch in the music writing world. What about it got you the gig, do you think?

A: I wanted to work for two magazines in particular when I got out of college: Pulse!, the magazine published by Tower Records, and Down Beat. I eventually wrote for both, and got a job at the former. I pitched a bunch of stuff to Tower Pulse!, but I think the first thing I wrote for them, in 1989, was something they pitched to me, an interview with the African-American funk-metal group named 24-7 Spyz, who were based in New York, which is where I lived. It was either 24-7 Spyz or a Souled American interview that was the first thing I wrote for Pulse! I wrote both those pieces in quick succession. I guess the first successful pitch I had, where the subject originated from me, was Hank Roberts, the electronically mediated cellist, who was a Knitting Factory regular. The pitch’s acceptance probably hinged on two things: I made a clear case for why he was important, and I balanced that with how his music was accessible.

Q: How has the field of writing about music changed since you became a music writer? Is it better or worse? What opportunities have disappeared? What opportunities are brand new?

A: For context, I wrote my first paid freelance article in either 1988 or 1989, and I was writing about music for the high school newspaper by 1981 or 1982, and wrote continuously about music in a college publication, from 1985 through 1988. There are, these days, fewer steady gigs at print publications, and fewer music-critic roles at newspaper organizations, but there are tons of online outlets, not just in the media, per se, but at organizations like orchestras, and music venues, and cultural institutions, and non-profits, and record labels — everything and everyone is potentially a “magazine” these days. One of the most knowledgeable music publications in the United States is the weekly newsletter of a record store in San Francisco called Aquarius. The pay these days is worse on average, not even adjusted for inflation, but there are far more places to publish. Thanks to things like WordPress and Tumblr and Quora, there are far more voices, which is wonderful, and the rise of comments has brought non-professional, but often quite informed, perspectives into the conversation. Music that was once under-represented, like hip-hop and contemporary classical, has come to dominate parts of the communal dialogue. Tools like Twitter, Facebook, and SoundCloud have probably done more to break down the wall between audience and performer than punk rock accomplished.

Q: What personal qualities do you posses that have kept you employed as a music writer? What qualities do you wish you had?

A: I guess the main thing is I’ve developed a point of view, maybe a reputation of some sorts for a point of view — that and a focus, an area or set of related areas in which I have some particular knowledge. That’s an interesting question about a quality I wish I had. There’s lots of stuff I’m working on doing better, but there’s no one thing in particular.

Q: Do you have a fulltime music writing job? How did you get it? Please describe some of your daily tasks.

A: No. I have in the past, but I don’t any longer. I applied to a music magazine when I got out of college, and then wrote freelance for them. I got to be a known entity to them, and when a position opened up they offered it to me. I was an editor there for seven years, and I edited everything from the letters page to columns to cover stories to comic strips. After I left I wrote freelance for them, including a column.

Q: Do you use different methods and tactics for writing a short form piece (review, sidebar) versus a long form piece (profile, longer cultural piece)?

A: Different forms require different approaches, certainly, but beyond that the assigning publication’s own sensibility and audience shapes the work.

Q: Aside from other music writing, where else do you find inspiration for your work?

A: Inspiration comes from lots of places — novelists, cookbooks, political writing, arts writing, writing by musicians. If you’re a brain surgeon, it may be best if you dedicate your study time to brain surgery. If you write about music, a broader range of reading and other input is highly recommended.

Q: Let’s play Desert Island Discs! If you were stranded on a desert island for 1 year (assuming you have food and shelter) and could only bring 3 songs, 2 objects, and 1 novel, what would they be?

A: I worked for seven years, and wrote for 15, for a magazine that featured Desert Island Discs every issue — Pulse! magazine, published by Tower Records. I’d bring Brian Eno’s Thursday Afternoon, which I guess counts as one song, since the album has just one track. I’d bring Johann Sebastian Bach’s Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007, for cello. I have so many versions of Bach’s solo cello suites that it’s hard to say which specific recording I’d bring, but I’d hope for one slightly slower than average. And I’d bring “Shhh / Peaceful” by Miles Davis. That’s the first half of his album In a Silent Way. Two objects? I’d bring a laptop and a solar charger. Just one novel? That’s very tough. I’d probably bring Bleak House by Charles Dickens. I promise if you ask me this question in a month I’ll have different answers, though the Brian Eno record would probably still be on there.

Q: Did you ever have a writing mentor? How did you find this person, and how did your relationship change/develop over time?

A: My mentors, to the extent I’ve had them, have been writers I’ve employed to write articles, writers far more advanced than myself. As an editor, I’ve had the opportunity to hire freelance writers whose work inspired me, among them Edith Eisler, Michael Jarrett, Linda Kohanov, Art Lange, Joseph Lanza, and Robert Levine. I learned by having long-running conversations with them. By editing their work I learned something about how it functioned, how they accomplished what they set out to do.

Q: What song title best describes your music writing career?

A: “In a Silent Way” (by Miles Davis).

Q: If you could go back in time and give advice to yourself at the beginning of your career, what would you say?

A: Stop trying to be interested in things other people are listening to that you don’t find interesting, and start paying more attention to what you do find interesting.

Q: Has an unexpected or out-of-the-box professional opportunity arisen from your work (ie: being in a documentary)? If so, what was it and how did it come about?

A: Lots of stuff. I’ve done a lot of public speaking to schools and organizations. I teach a course about sound at an art school. I’ve done music supervision for a documentary. Lots of stuff. Most of this was the result of someone appreciating something I did and then contacting me. In some cases, a conversation with another professional led to a collaboration, though that wasn’t the intention for the conversation.

Q: What’s the most unique angle for a music writing piece you’ve had? How did you arrive at it?

A: A lot of “angle” writing comes across as gimmick to me. Sometimes the result is that the subject of, say, a profile responds well, but that’s arguably not because the angle itself was of interest, but because the subject was just glad to have someone do something different for once, rather than ask variations on “the influence question.” One thing I’m proud of as an editor is “conversation” interviews I’ve arranged, like having Randy Weston and La Monte Young meet in person to talk about playing the blues. I suppose that was a sort of angle, since neither of them was in each other’s immediate cultural orbit, and they definitely enjoyed the experience, and I think readers did, too. I’d say the best “angle” work I’ve done is as an editor: assigning the right person to do a story, often someone who is not a professional music critic, like getting Richard Kadrey, then best known as a cyberpunk novelist, to interview the band Ministry, or getting Geoff Nicholson, also a novelist, to interview a band we’d determined to put on the cover but whom I had no passion for, Bush. In the latter case, I saw it as a commercial situation — it made sense to put the band on the cover — and Nicholson had just written a book that took place in a British department store, so he seemed appropriate for the task. I also assigned for a full decade a wide variety of comics about music, and the exploration of music through visuals was a tremendous learning experience for me. I guess that format counts as an “angle,” too.

There were, in addition, some questions I wasn’t sure I had productive responses to, among them: What are the 5 things (objects? rules?) every music writer needs? How can a new generation of music writers combat the challenges that music writing currently faces? And: In your opinion, what differentiates music writing from other types of writing (straight journalism, literary nonfiction) if anything?

More on the book at 333sound.com/howtowriteaboutmusic.

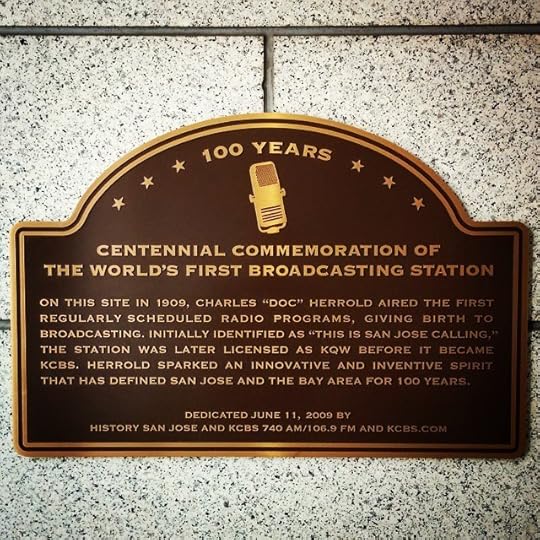

via instagram.com/dsqt

Early radio. Plaque on wall of building next to San Jose Museum of Art. #soundstudies

Cross-posted from instagram.com/dsqt.